Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 160

January 15, 2019

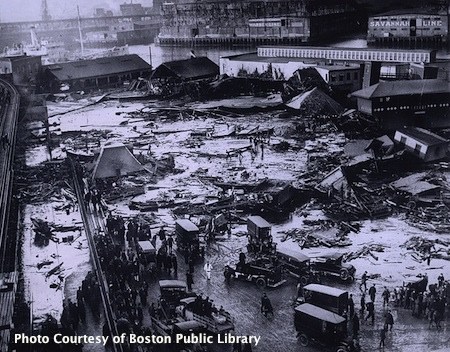

The Physics of the Boston Molasses Flood [video]

Building on her earlier fluid-dynamics research about the Boston Molasses Flood, Nicole Sharp made this new video:

For more of the history of that flood see Cara Giamo’s “The Boston Molasses Flood Is Worth Taking Seriously” in Atlas Obscura, and Jennifer Ouelette’s “Incredible physics behind the deadly 1919 Boston Molasses Flood” in New Scientist.

2018 in Hair (Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists™)

Christian Steven Hoggard

The 2018 Members Gallery for The Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists is now available to the public.

Once a year, we gather the listings of all the new inductees into such a gallery – before that, new inductees are only seen individually (in the Improbable Blog) as they join throughout the year.

We invite you to admire these new members, their accomplishments, and also their hair.

This new gallery includes the 2018 inductees into all 6 sibling hair clubs:

The Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists

(LFHCfS)

(LFHCfS)The Luxuriant Former Hair Club for Scientists

(LFHCfS)

(LFHCfS)The Luxuriant Facial Hair Club for Scientists

(LFHCfS)

(LFHCfS)The Luxuriant Flowing, Former, or Facial Hair Club for Social Scientists

(LFFFHCfSS)

(LFFFHCfSS)The Luxuriant Flowing, Former, or Facial Hair Club for Engineers

(LFFFHCfE)

(LFFFHCfE)The Luxuriant Flowing, Former, or Facial Hair Club for Science Journalists

(LFFFHCfSJ)

(LFFFHCfSJ)

Emily Hofstetter

THE STATE of the HAIR CLUBS

The state of the hair clubs is strong! In 2018 the clubs gained 6 new members from 5 countries, for a grand total of 567 members. We have not finished calculating the aggregate length of the new members’ hair.

NOMINATE for MEMBERSHIP

Do you believe that you or someone you know qualifies to be in one of these luxuriant flowing hair clubs for scientists? Or is there someone who deserves to be an Historical Honorary member?

NOTE of DISTINCTION

Please note that the LFHCfS is distinct from the “Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men”. That said, we enjoyed watching their video. Bravo gents. Let us know if any of you are also a scientist.

January 14, 2019

Recent progress in Quantum Geography

It was back in 1994 that Dr William Peterman (then at the University of Illinois at Chicago) mooted the idea of ‘Quantum Geography’ (QG) with an article for the journal The Professional Geographer, Volume 46, 1994 – Issue 1, entitled : ‘Quantum Theory and Geography: What Can Dr. Bertlmann Teach Us’. Dr. Peterman examined the possibilities of attaining objectivity in “quantum-diffracted social sciences” suggesting that :

“By exploring the implications of modern physics, geographers may be able to develop better ways of describing and understanding social space and to incorporate meaning and values as important dimensions.”

The “Dr. Bertlmann” [see Fig. 1] cited in the title had been thrown into the limelight 13 years earlier by the world-renowned particle physicis John Stewart Bell FRS of CERN, in his paper for Journal de Physique Colloques, 1981, 42 (C2), pp.C2-41-C2-62, BERTLMANN’S SOCKS AND THE NATURE OF REALITY.

“The case of Bertlmann’s socks is often cited. Dr. Bertlmann likes to wear two socks of different colours. Which colour he will have on a given foot on a given day is quite unpredictable. But when you see (Fig. 1) that the first sock is pink you can be already sure that the second sock will not be pink. Observation of the first, and experience of Bertlmann, gives immediate information about the second.”

It’s fair to say that since the introduction of the Quantum Geography concept in 1994, the flow of academic papers devoted to the subject could be described, at best, as a trickle. A factor that may have been responsible for prompting a critical review, in 2016, by Dr. Thomas S J Smith, of the University of St Andrews, Scotland, who tracked Quantum Geography’s progress, asking : ‘What ever happened to quantum geography? Toward a new qualified naturalism‘ (in Geoforum, Volume 71, Pages 5-8)

“Geographers have long been aware that spatial imaginaries matter and these developments are thus concluded to be of profound interest, not least with implications for key reconceptualisations of subjectivity, consciousness, objectivity, space, time and causality. It is put forward that the implications of quantum research may well provide fertile ground for engagement with qualified naturalism, and new, explicitly post-classical spatial imaginaries.”

UPDATE: Since the publication of ‘What ever happened to quantum geography?’ A new paper on the subject has been published – hinting not just at its resurgence, but its re-invention.

Professor Thomas Bittner of the Departments of Philosophy and Geography, State University of New York, Buffalo, US, is the author of ‘Towards a Quantum Theory of Geographic Fields‘

“The non-commutative nature of certain operations is the hallmark of Quantum Mechanics. For example, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is a consequence of the noncommutativity of operators that determine the position and the momentum of a particle. It is the aim of this paper to present an adequate theory of geographic fields by applying ideas and techniques from quantum mechanics to geographic fields. This set of ideas and techniques applied to geographic phenomena will be called Quantum Geography (QG).”

Which, the author says, will allow for “ ontological vagueness” – which could be applicable to the study of geographic fields.

“QG allows for geographic fields that are in indeterminate states and thereby provides means for the expression of ontological vagueness. According to QG ontological vagueness has two interrelated aspects: quality indeterminacy and localization indeterminacy.”

[ Research research by Martin Gardiner ]

January 11, 2019

A Taxonomy of Ubiquitous Little Plastic Thingies

The Holotypic Occlupanid Research Group occupies itself by doing “research in the classification of occlupanids.” They explain: “These small objects are everywhere, dotting supermarket aisles and sidewalks with an impressive array of form and color.”

Much of their work in on display at the Holotypic Occlupanid Research Group’s web site.

Some years ago, Eric Grundhauser wrote an archaeological treatise. for Atlas Obscura, about these (in many cases) patented thingies: “Most of the World’s Bread Clips Are Made by a Single Company“

January 10, 2019

The Gendering of the Ear in Early Modern England (new study)

“While critics discuss the link between female speech and sexual looseness, and silence and chastity, many have overlooked the prerequisite for obedience – hearing and its agent, the ear. The link between the ear and vagina is often ignored because of the proneness to perceive ears as passive orifices (Kilgour 131; Woodbridge 256). However, ears are vulnerable holes subject to penetration by external tongues.”

– explains Bilal Hamamra who is professor of English Literature at the Department of English Language and Literature, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine, in a shortly to be published note for the scholarly journal ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews.

See: ‘The Gendering of the Ear in Early Modern England‘ in ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, ahead-of-print, pp. 1–2 (available to purchase at £30 from the Taylor & Francis Group).

Also see (ear canal insertions related) : The iPod — a shield, weapon, or both?

[ Research research by Martin Gardiner ]

January 9, 2019

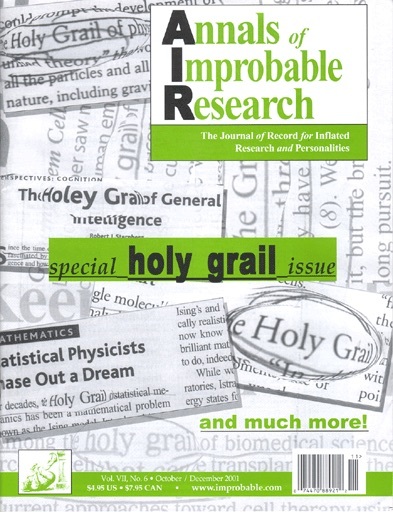

The Holy Grail Re-Redux: Notes of a Retiring Grail Watcher

The Holy Grail Re-Redux: Notes of a Retiring Grail Watcher

by Steve Nadis

Boys of my generation were encouraged to have a hobby. Some of my peers took up coin and stamp collecting; others caught butterflies and beetles, hoarded baseball cards and comic books, or built model ships and planes. I chose a rather unusual pastime—combing the popular and technical literature for references to the holy grail in various contexts, scientific and otherwise. I was excited to take part in the celebrated hunt for a long-sought prize, carried out in bygone days by legendary actors—the Knights of Columbus, the Masonic Knights Templar, and other fraternal orders. If only I could gather enough clues, I surmised, maybe I could be the one to find the treasure and thereby make my mark in history. This, indeed, was the stuff of dreams.

Boys of my generation were encouraged to have a hobby. Some of my peers took up coin and stamp collecting; others caught butterflies and beetles, hoarded baseball cards and comic books, or built model ships and planes. I chose a rather unusual pastime—combing the popular and technical literature for references to the holy grail in various contexts, scientific and otherwise. I was excited to take part in the celebrated hunt for a long-sought prize, carried out in bygone days by legendary actors—the Knights of Columbus, the Masonic Knights Templar, and other fraternal orders. If only I could gather enough clues, I surmised, maybe I could be the one to find the treasure and thereby make my mark in history. This, indeed, was the stuff of dreams.

My mother regularly complained about the box of newspaper and magazine clippings I left in the family room, the contents of which I often spread on the rug while watching episodes of “Gunsmoke,” “Bonanza,” and other popular shows of that era. “Why don’t you get a real hobby?” she sometimes asked. My father, meanwhile, was disappointed when I didn’t want to play horseshoes or toss the baseball with him, opting instead to grab my scissors and back issues of Time, Life, Popular Science, and Popular Mechanics in order to make incremental additions to my burgeoning holy grail scrapbook.

It was painstaking work, but I justified it—to myself and others—by paraphrasing John F. Kennedy’s famous remarks: “We choose to search for the grail, and do other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard—because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.” That speech was effective in silencing most critics, as well as in motivating me.

The pursuit of the grail was a major preoccupation that kept me from being popular in school and from being an honors student. I never engaged in graduate studies, or got a law or medical degree, as did many of my high school and college classmates, but I also never wavered from my chosen path. I accepted the challenge, as JFK said. I would not postpone it, and I was determined to win, even though I didn’t really know what winning meant or looked like in this venture.

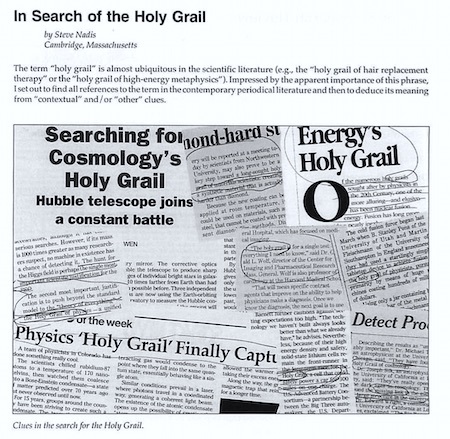

My grail quest was a lonely one for many years, carried out briefly in the family room and soon in the backyard shed (where my father placed my box and scrapbook), then to my college dorm room, my bedroom in a Cambridge house share, and eventually in an alcove in my own home dedicated to all things grail. It was not until 1995 that the editor of a prestigious journal took an interest in my labors and asked me to write a feature-length article that summarized my efforts in this grand enterprise. That turned out to be, in the eyes of many observers, my seminal piece, “In Search of the Holy Grail,” followed half a decade later by another classic of the genre, “The Holy Grail Redux,” and five years hence by “In Search of Astronomy’s Holy Grail,” plus the equally memorable companion piece, “Deconstructing Astronomy’s Holy Grail.”

A talk I gave at the AAAS 2008 Annual Meeting in Boston, “My Search for the Holy Grail,” was arguably the high point of my career. I recounted my adventures to an audience of hundreds that filled one-and-a-half ballrooms, and could easily have filled two ballrooms had the back portion of the room not been reserved for tango lessons—an exercise, in my estimation, of dubious scientific value. A year later, I collaborated with a younger grail investigator—a scholar of great promise who has since abandoned the calling—on what turned out, until today, to be my last printed words on the subject, “A Crusade Against the Quest for the Holy Grail.”

Since then, I’ve been asked to give further talks, as well as to publish my latest findings—all of which I’ve politely declined. But I now believe that an explanation is in order. Simply put, I am retiring from the grail hunt, in part because I have reached the standard retirement age, though there is an even more compelling reason. And pardon me if I, once again, invoke the spirit, if not the exact phraseology, of the late President Kennedy: I am giving up the hunt not because it is too hard for someone of my age, but rather because it is too easy.

In the old days, I used to read voraciously, plowing through stacks of periodicals for the fleeting grail reference. I would cut out articles and paste them into my ledger. There was a whole network of grail searchers scattered around the world who would pass on interesting tidbits to me by mail, sometimes ringing by phone (collect, generally, which often proved to be a costly indulgence) so that I could hear and transcribe the words immediately, rather than wait for our postal service to reach my remote dwelling.

Nowadays, the thrill is gone, and much of the blame goes to Google. We’ve entered the age of “Big Data” and informatics, where the quirks and nuances of my field are rapidly disappearing as number crunching and analytics take the place of good old-fashioned detective work.

Allow me to illustrate: Five long years passed between the publication of “The Holy Grail Redux” and “In Search of Astronomy’s Holy Grail” and “Deconstructing Astronomy’s Holy Grail”—years filled with research and relentless digging, fueled by a passion to bring long-buried facts to life. But now I can use my browser to search on “the holy grail of astronomy” and instantly get 11,100 entries (two of the first eight being my aforementioned articles!). Yes, I can obtain 11,100 leads, 11,100 pieces of evidence, within a fraction of a second, and where’s the sport in that? Like shooting a barrel in fish, as my uncle Harold used to say. Put in other terms, skilled professionals like me are no longer needed because everyone can, with a few keystrokes, carry out grail searches of their own. I suppose that could be called progress—the democratization of a formerly arcane mission—though I’m mindful of the potential pitfalls such as the diminution of standards and erosion of rigor, to mention a few…

Take the prompt “the holy grail of particle physics,” for instance, which yields 119,000 results, whereas “the holy grail of cosmology” delivers a bit less at 107,000 results. Here are some other examples (presented in ranked, descending order), as gleaned from the world’s leading search engine:

• “the holy grail of cancer treatment” –19,600

• “the holy grail of condensed matter physics” — 1,240

• “the holy grail of farts” — 480

• “the holy grail of competitive eating” – 126 (possibly related to the former?)

• “the holy grail of exoplanets” — 92

• “the holy grail of flu vaccines” — 89

• “the holy grail of astrobiology” — 85

• “the holy grail of gene editing” — 62

• “the holy grail of peanut butter” — 60

• “the holy grail of fish tacos” — 49

• “the holy grail of SETI” — 29

• “the holy grail of plastics” — 28

• “the holy grail of deep-dish pizza” — 7

• “the holy grail of flatulence” — 7 (another possible connection with the Chicago-style treat mentioned above?)

• “the holy grail of insomnia” — 6

• “the holy grail of the zipless f***” — 5

• “the holy grail of male pattern baldness” — 3

• “the holy grail of fried rice” — 2

• “the holy grail of high-temperature superconductivity” – 1

• “the holy grail of hair transplants” — 1

• “the holy grail of chicken teriyaki” — 1

• “the holy grail of smoked salmon” — 1

• “the holy grail of diarrhea” — 1 (with no aspersions cast to the fishing and fish-processing industries)

• “the ‘holy grail’ of freeze dried whole blood, in the form of a unit of autologous whole blood, pre-collected, dried and carried…” — 1

• “the holy grail of blackened catfish” — 0

• “the holy grail of three-bean salads” — 0

• “the holy grail of shrimp fried rice” — 0

• “the holy grail of Monty Python and the holy grail” — 0

So, you might be wondering, what have I learned from this undertaking? One goal of the endeavor was to document the use and misuse of the term “holy grail,” as well as to see how the term’s definition has evolved (or devolved) over time.

It should be clear from the foregoing that the holy grail, in current parlance, is not a single, fixed object such as a magical cup or platter that a reader of this article is likely to pick up in his or her hands and proudly display to the world. It is, instead, a more malleable, abstract, and elusive concept—one that is constantly shifting and diversifying, perhaps representing the diversification of contemporary society. I now believe, some decades into the game, that no matter how hard people search, they are never going to find the holy grail in a definitive, absolute sense. Today it stands for something just out of reach, something to be strived for. And if someone lays claim to a specific grail, a claim that may well be contested, other grails will surely emerge—that one replaced by many, inspiring us to push forward, just as I have been inspired for numerous decades.

In my retirement days, which loom ahead, I won’t be trading in all that excitement for a round or two of golf. But I might enjoy the occasional game of whist or cribbage, played next to a fireplace, in a recess of which stands a goblet that can and in fact has been traced back to the Last Supper.

BONUS: Here’s video of another grail hunter, giving “A Seminar On The Holy Grail Of Particle Physics”:

January 8, 2019

“Woodpeckers don’t play football” – new viewpoints on concussion prevention in sports

A newly published editorial in the British Journal of Sports Medicine draws attention to what it calls the ‘misguided’ use of commercial devices that are intended reduce so-called ‘Brain Slosh’ by compressing the jugular veins of sportpersons – with the idea of mitigating the risks of concussion. “Unfortunately” the authors say, “this woodpecker-inspired concept is misguided for numerous reasons.” And they give no less than five reasons why. For example :

A newly published editorial in the British Journal of Sports Medicine draws attention to what it calls the ‘misguided’ use of commercial devices that are intended reduce so-called ‘Brain Slosh’ by compressing the jugular veins of sportpersons – with the idea of mitigating the risks of concussion. “Unfortunately” the authors say, “this woodpecker-inspired concept is misguided for numerous reasons.” And they give no less than five reasons why. For example :

“Woodpeckers do not use jugular occlusion. Proponents of jugular venous compression claim that woodpeckers contract their omohyoid muscle to occlude the jugular vein during pecking, and replicating this mechanism in humans has potential value for brain protection. Although this claim is commonly cited in promotional material and mainstream coverage as a fact or recent discovery, it is not actually described or hypothesised anywhere within the woodpecker literature.”

Note : The 2006 Ig Nobel Prize for Ornithology was awarded to Ivan R. Schwab, of the University of California Davis, and the late Philip R.A. May of the University of California Los Angeles, for exploring and explaining why woodpeckers don’t get headaches.

The photo : Shows the ‘Q Collar’ from Q30innovations , which is cited in the editorial.

January 7, 2019

“Pernickety” – tracing a word’s origin(s)

The exact origin(s) of the word ‘Pernickety’ are lost in the mists of time. In particular, the Scottish mists of time. Clues nevertheless exist. And have been painstakingly investigated by Professor William Sayers, B.A., fil. kand., M.A., Ph.D., of the Medieval Studies Program, College of Arts and Sciences, at Cornell, who notes that :

“In Scotland are found such forms as pirnicky, pernicky, pernicked, pernicket, pernickett, pirnickerie, pernigglety, pick-nickerties, and pernicketies, while in America a major variant appeared (from 1892 onwards) in persnickety and comparable forms.”

Several questions about ‘pernickety’ apparently remain unanswered though :

“How to account for the–s–of the North American form? Can per–again have been sensed as a perfective prefix and–nick-recast as snick ‘a small, quick, and neat cut’, thus a discriminating actor statement?”

See: ‘Pernickety’ by William Sayers, in Scottish Language, 29 (Annual 2010): p87+

Bonus : Professor Sayers has also written extensively on Cant, Rant, Gibberish, and Jargon in ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, Volume 28, 2015 – Issue 1.

[ Research research by Martin Gardiner ]

January 4, 2019

The Meaning of Shoes—Specifically, of the Word “Shoes”

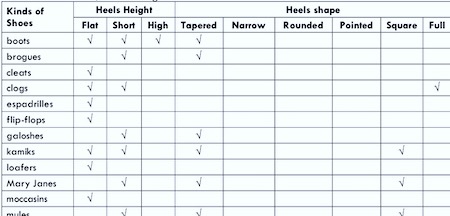

Shoes can be meaningful, sure. The word “shoes” is full of meaning, as are words for particular varieties of shoe. This study tries to make that clear:

“A Look at the World Through a Word ‘Shoes’: A Componential Analysis of Meaning,” Miftahush Shalihah, Journal of Language and Literature, vol. 15, no. 1, 2015, pp. 81-90. The author, at Sanata Dharma University, Indonesia, explains:

“Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes.

The study includes a detailed chart of shoe characteristics. Here is the top part of that chart:

The study concludes with a flourish:

CONCLUSION—The theory that is served in the discussion is used to analyze the distinctive features of the word shoes. By having this analysis, the writer hopes that the reader can have a better understanding on the differences of each type of the shoes. The writer also provides a table so that the reader can see the differences more clearly.

BONUS: The author’s master’s thesis looked for meaning elsewhere, as is clear from the document’s title: “A Pragmatic Study of Humor in Asterix at the Olympic Games Comic.”

January 3, 2019

Natesto®. What Else? (drug-naming study)

If you’re a manufacturer of medicines, thinking up a suitably snappy name for (2S)-1-[(2S)-6-amino-2-{[(1S)-1-carboxy-3-phenylpropyl]amino}hexanoyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid [generic name Lisinopril] might not be an easy task.

If you’re a manufacturer of medicines, thinking up a suitably snappy name for (2S)-1-[(2S)-6-amino-2-{[(1S)-1-carboxy-3-phenylpropyl]amino}hexanoyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid [generic name Lisinopril] might not be an easy task.

And, according to a recent paper in the journal Names : A Journal of Onomastics, Volume 66, Issue 2, 2018, picking the ‘wrong’ name can make a huge difference to your sales figures.

“Considering the huge amount of money devoted to the marketing of new drugs, drug sponsors cannot take the risk of releasing a drug that will not sell. As seen with the contrasting stories of the two brands of lisinopril, both launched in the late 1980s: “ICI Pharmaceuticals called its lisinopril Zestril. Its competitors marketed the same molecule as Carace. Whereas Zestril became one of the medical world’s most successful brands, Carace sank pretty much without trace.”

The author of the study, Dr Pascaline Faure, who is a director of the Département d’Anglais Médical de la Faculté de Médecine Pierre et Marie Curie (Pitié-Salpêtrière/Saint-Antoine), France, points out that although the US regulatory body, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has ‘recommended’ that “unsubstantial beneficial” connotations in names should be banned, manufacturers continue to concoct imaginative new tradenames in the hope that they will encourage sales.*

“In our study, we have shown that the commonly used letters X and Z are giving way to A and O endings so as to attract Romance languages speaking clients and conquer other markets such as the Latin American and the European markets. We have demonstrated that this trend matches a less recent ploy in food and automotive marketing. We focused on the “Vowel/Consonant+lexeme” matrix that is found almost exclusively in the drug industry because it permits to create a name shorter in writing – an advantage for prescribers. Although the FDA recommended that “unsubstantial beneficial” connotations be banned, we have uncovered the presence of promotional affixes as well as hidden emotional contents that are meant to be persuasive.”

See: ‘ Natesto®. What Else? New Trends in Drug Naming’

* Bonus Assignment [optional] : Are the names designed to appeal to patients, or doctors (or both)?

Note: Bearing in mind that the patent on Lisinopril has long since expired, patients should be able to buy a chemically identical generic version of Lisinopril at a lower price than a branded version – but for those who insist on a named brand, there are quite a few on offer – here is a partial list :

Acebitor®, Acemin®, Acepril®, Acerdil®, Acetan®, Acinopril®, Adco-Zetomax®, Adicanil®, Agimexpharm®, Agimlisin®, Alapril®, Albigone®, Axelvin®, Biopril®, Bpmed®, Cardiostad®, Cipril®, Cotensil-GMP®, Dapril®, Dikepril®, Diroton®, Diyiluo®, Doneka®, Dosteril®, Doxapril®, Ecapril®, Enlisin®, Eucor®, Fisopril®, Forsine®, Gamalizin®, Genopril®, Glopril®, Gnostoval®, Hipril®, Hyporil®, Icoran®, Ikapril®, Inhitril®, Interpril®, Iricil®, Irumed®, Laaven®, Leruze®, Likenil®, Linipril®, Linopril®, Linoxal®, Linvas®, Lipril®, Liscard®, Lisdene®, Lisi-Hennig®, Lisidigal®, Lisigamma®, Lisigen®, Lisihexal®, LisiHEXAL®, LisiJenson®, Lisinal®, Lisino®, Lisinocor®, Lisinoratio®, Lisinospes®, Lisinovil®, Lisipril®, Lisiprol®, Lisiren®, Lisitril®, Lisodinol®, Lisodura®, Lisopress®, Lisopril®, Lisoril®, Lispril®, Listril®, Lithium-Chlorid®, Lizinopril®, Lizopril®, Lizro®, Lokopool®, Longes®, Lopril®, Loril®, Lysin®, Maxipril®, Nafordyl®, Neopril®, Nivant®, Noperten®, Nopril®, Noprisil®, Odace®, Omace®, Optimon®, Perenal®, Pressamea®, Pressuril®, Prinivil®, Quadrica®, Ranolip®, Ranopril®, Rilace®, Safepril®, Sinopren®, Sinopril®, Sinopryl®, Skopryl®, Stril®, Tensikey®, Tensinop®, Tensiphar®, Tensopril®, Tersif-MD®, Thriusedon®, Tivirlon®, Tonolysin®, Tonotensil®, Vastril®, Vercol®, Veroxil®, Vitopril®, Yi-Mai-Ou®, Yijikang®, Z-Bec®, Zesger®, Zestan®, Zestril®, Zinopril®. [source]

[ Research research by Martin Gardiner ]

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers