Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 159

January 20, 2019

Which Eats Its Own Faster, the Tortoise or the Hare?

Which is quicker to resort to cannibalism—tortoises or hares? Here’s one side of the story, a report by National Geographic. We must await evidence for the other side. (Thanks to Mark Benecke for bringing this to our attention.)

Details about the eating are in a study published in BioOne: “Scavenging By Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus) In Yukon, Canada,” by Michael JL Peers, Yasmine N Majchrzak, Sean M Konkolics, Rudy Boonstra, Stan Boutin.

January 18, 2019

Will An Indian Win The Ig Nobel?

Vasudevan Mukunth writes, in The Wire:

Will An Indian Win The Ig Nobel?

instead of endorsing the view that an Indian will a Nobel Prize by 2035, the Government of India should aspire to have an Indian win an Ig Nobel Prize within the next two decades if the intent is to target a prize at all.

Although there is an apparent sense of ridicule in the prizes’ premise, it is gentle and in fact uplifting. A government should aspire to help its country’s scientists win an Ig Nobel Prize because the government, at least some department of it, has tremendous influence on the national research culture and research priorities. In this framework, to win an Ig Nobel Prize would mean being able to work on what scientists deem worth their while. This in turn would require the presence of a research evaluation scheme that is fair, efficient and not very exacting, allowing scientists the time to work on projects that catch their fancy without consequence for their career advancement or other responsibilities.

January 17, 2019

Did Bigger Penises Evolve to Protect Hermit Crabs’ Private Property?

Sex, economics, evolution, and stuckness all play roles in this new study about the evolution of larger penises in hermit crabs:

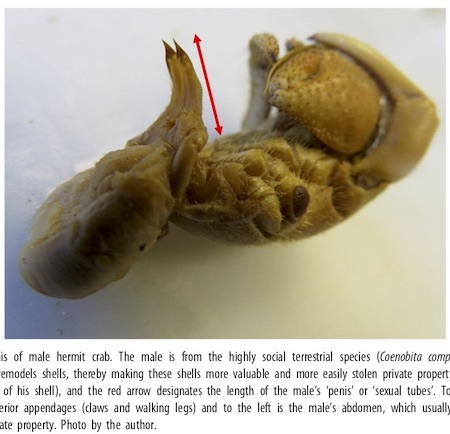

“Private parts for private property: evolution of penis size with more valuable, easily stolen shells,” Mark E. Laidre, Royal Society Open Science, epub 2019. (Thanks to Thomas Michel for bringing this to our attention.) The author, at Dartmouth College, explains:

the importance of private property in driving penis size evolution has rarely been explored. Here, I introduce a novel hypothesis, the ‘private parts for private property’ hypothesis, which posits that enlarged penises evolved to prevent the theft of property during sex. I tested this hypothesis in hermit crabs, which carry valuable portable property (a shell) and which must emerge from this shell during sex, risking social theft of their property by eavesdroppers. I measured relative penis size (penis-to-body ratio) for N= 328 specimens spanning nine closely related species. Species carrying more valuable, more easily stolen property had significantly larger penis size than species carrying less valuable, less easily stolen property, which, in turn, had larger penis size than species carrying no property at all.

You can perhaps see how this plays out, by watching a short video by Sara Lewis and Randi Rotjan, called “Social Networking by Hermit Crabs”:

Abby Olena has an essay about the new study, in The Scientist: “Larger Hermit Crab Penises May Prevent Shell Theft.”

“A Jackass and a Fish”—Doctors save the life of a Fish-Called-Wanda imitator

This young man who swallowed a fish

As part of a party tradish-

ion he followed with friends:

Unhappy? Depends.

The young man has gotten his wish.

That limerick is a hasty summary of the medical case described in this newly published study:

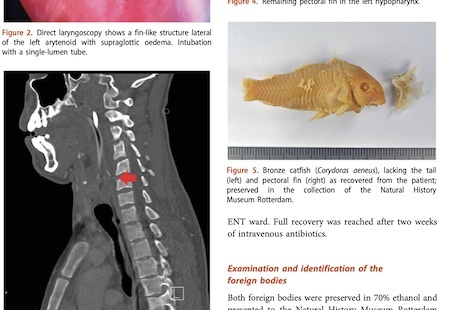

“A Jackass and a Fish: A Case of Life-Threatening Intentional Ingestion of a Live Pet Catfish (Corydoras aeneus),” Linda B.L. Benoist, Ben van der Hoven, Annemarie C. de Vries, Bas Pullens, Erwin J.O. Kompanje, and Cornelis W. Moeliker, Acta Oto-Laryngologica Case Reports, vol. 4, no. 1, 2019. The authors explain:

Inspired by Jackass (a tv-show about self-injuring stunts), some friends topped off a drinking party with live fishes from their aquarium. After the goldfishes had gone down smoothly, a bronze catfish was ingested. Unaware of the morphology and anti-predator behaviour of this species, a healthy but intoxicated 28-year-old man got a surprise. The catfish erected and locked the spines of its pectoral fins and got lodged in the hypopharynx. After several hours, he presented himself at the emergency department with dysphonia and dysphagia. The fish had to be removed endoscopically. Intubation and admittance to the intensive care unit was necessary due to laryngeal oedema. Two weeks postoperatively, the patient made a full recovery and donated the fish to the Natural History Museum Rotterdam. The publicity generated by public exhibition of the ‘do-not-swallow-fish’ emphasised the official Jackass warning: ‘.. do not attempt any of the stunts you’re about to see’.

Every doctor who was called in to help with the case ended up as a co-author of this study. Another co-author, C.W. (Kees) Moeliker, is the Ig Nobel Prize-winning discoverer of homosexual necrophilia in the mallard duck, and is also director of the Natural History Museum in Rotterdam. A few years ago the museum hosted the first public medical discussion of this case, a discussion that has now matured to become this study.

Among the knowledge sources cited in this paper, one stands out: “Cleese J, Crichton C. A fish called Wanda. Beverly Hills (CA): Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Production; 1988.” The young man who swallowed the fish was inspired by this scene from the movie:

Philosophical disagreements on possible reason(s) ‘Why Flatulence is Funny’ – Professor Sellmaier v. Professor Spiegel

If you want a reliable method of raising laugh, you can always resort to references of flatulence – a comedic ploy that goes back (at least) 2000 years. But the question as to why it’s considered funny, remains, to this day, a hotly debated subject.

In 2013, Professor James Spiegel of the Philosophy Department at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, US, took a stab at explaining the phenomenon in issue 35 of the journal ‘Think’ (a journal of The Royal Institute of Philosophy, UK)

“[…] flatulence is a phenomenon that prompts a sudden sense of superiority, is incongruous with many aspects of human social life, and creates a constant exertion of mental energy from which we all need relief from time to time.”

See: ‘WHY FLATULENCE IS FUNNY’

4 years later, however, in the same journal, Prof. Dr. Stephan Sellmaier of the Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences at Ludwig Maximilian-Universität, München., Germany, gave a blow by blow account of no less than five ‘problematic issues’ with Prof. Spiegel’s essay,

• (1) His claim that laughter always results from a pleasant psychological shift is false.

• (2) His argumentative move from what makes paradigm cases funny to what makes flatulence funny is unwarranted.

• (3) His notion of a psychological shift is not specific enough and lacks explanatory power.

• (4) The claim that funniness of flatulence involves superiority is doubtful.

• (5) His talk about ‘nervous energy’ is questionable and has implausible implications

See: CUT TO THE CHEESE – REPLY TO SPIEGEL’S ‘WHY FLATULENCE IS FUNNY’

The illustration is a detail from the He-Gassen scroll (c. 1603–1868)

[ Research research by Martin Gardiner ]

Building conclusions from the remnants of excreted hare bones

“How did they reach that conclusion? … If you eat a shrew whole, and excrete its bones, the bones will have specific hallmarks of human digestion, typified by the concentration of stomach acid and so on. In fact a scientific team won an Ig Nobel Prize in 2013 for studying what happens to shrew bones if the micro-mammal is eaten whole by a human.”

So explains a news report in Haaretz, about a new study: “Prehistoric People Hunted With Dogs in Jordan, Archaeologists Conclude From Hare Explosion.”

This photo shows some of the bone fragments studied in the, er, study:

January 16, 2019

Stripes painted on the body protect against blood-sucking insects

The Swedish and Hungarian researchers who won an Ig Nobel Prize (in 2016) for discovering why white-haired horses are the most horsefly-proof horses, and for discovering why dragonflies are fatally attracted to black tombstones have published a new study, extending their work—to use painted stripes to protect human life.

A report in Forskning, in Swedish, explains [here is a machine translation of that]:

Stripes on the body protect against blood sucking insects

Painted stripes on the body protect the naked skin from insect bites. It is the first time scientists have managed to prove that body painting has this effect. Painting the body thus provides protection against insect-borne diseases….

A Swedish-Hungarian research team now shows that body painting provides protection against the insects. A brown plastic model of a human attracts ten times as many brakes compared to a dark model painted with light stripes. The researchers also find that a beige plastic doll that they used as a control model attracts twice as many blood sugars as the striped model.

According to Susanne Åkesson, professor at the Department of Biology at Lund University, it is the first time that researchers find experimental support that body painting reduces the risk of insect attacks….

The experiment was done in Hungary. Part of the research team is based at Eötvös Loránd University.

The study is: “Striped bodypainting protects against horseflies,” Gábor Horváth, Ádám Pereszlényi, Susanne Åkesson, and György Kriska, Royal Society Open Science, epub 2019.

Here are other news accounts, in Hällekis, and in Helsingbords Dagblad. An illustrated account in Phys.org carries the headline ” ‘Zebra’ tribal bodypaint cuts fly bites 10-fold: study.”

A Look in the Brains of Publication-Hungry Brain Scientists

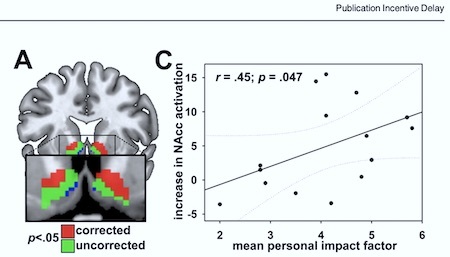

“The idea that one can study scholar journal publishing behavior by looking at their brain’s fMRI response to the ‘journal impact factor‘ of the journal is, to an academic serials librarian at least, incredibly funny. I suppose this is the serious-professor version of hooking up a child to an fMRI and offering them their favorite candy.” That’s the word from Melissa Belvadi, Collections Librarian at the University of Prince Edward Island, who alerted us to this study:

“Journal impact factor shapes scientists’ reward signal in the prospect of publication,” Frieder Michel Paulus, Lena Rademacher, Theo Alexander Jose Schäfer, Laura Müller-Pinzler, and Sören Krach, PloS One, vol. 10, no. 11, 2015, e0142537. The authors, at the the University of University of Lübeck, Germany, explain:

The incentive structure of a scientist’s life is increasingly mimicking economic principles. While intensely criticized, the journal impact factor (JIF) has taken a role as the new currency for scientists. Successful goal-directed behavior in academia thus requires knowledge about the JIF. Using functional neuroimaging we examined how the JIF, as a powerful incentive in academia, has shaped the behavior of scientists and the reward signal in the striatum. We demonstrate that the reward signal in the nucleus accumbens increases with higher JIF during the anticipation of a publication and found a positive correlation with the personal publication record (pJIF) supporting the notion that scientists have incorporated the predominant reward principle of the scientific community in their reward system….

Thus, the JIF as a novel and powerful paradigm in academia has already shaped the neural architecture of reward processing in science.

Here’s visual detail from the study:

NOTE: Some people might suggest that this study was intended to be a joke.

January 15, 2019

Correcting Some Physiology in Gulliver’s Travels, After 300 Years

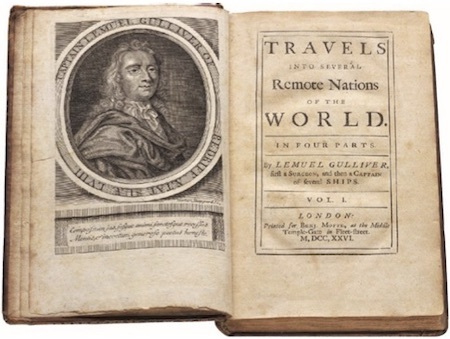

Editing can be a slow process. A new study suggests that a famous novel published three centuries ago could and should be edited to correct a calculation error. The study is:

“Physiological Essay on Gulliver’s Travels: A Correction After Three Centuries,” Toshio Kuroki, The Journal of Physiological Sciences, epub 2019. (Thanks to Mark Dionne for bringing this to our attention.) The author, at the Research Center of Science Systems, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Tokyo, Japan, explains:

“Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, published in 1726, was analyzed from the viewpoint of scaling in comparative physiology. According to the original text, the foods of 1724 Lilliputians, tiny human creatures, are needed for Gulliver, but the author found that those of 42 Lilliputians and of 1/42 Brobdingnagians (gigantic human creatures) are enough to support the energy of Gulliver. The author further estimated their heartbeats, respiration rates, life spans and blood pressure…. Their blood pressures were estimated with reference to that of the girafe and barosaurus, a long-neck dinosaur. Based on the above findings, the food requirement of Gulliver in the original text should be corrected after almost three centuries.”

This, Kuroki further explains, was an almost-complete surprise:

“It is indeed surprising for me that nobody noticed this simple error for three centuries since publication in 1726. To the best of my knowledge, the only two exceptions are Max Kleiber, University of California at Davis, who published in 1967 a book chapter on this issue, but used misestimated values of Lilliputian height and did not take BMI into account . More recently, in 2014, A. J. Hulbert, University of Wollongong, Australia, published an article on Kleiber’s law, in which Gulliver’s Travels were briefly mentioned.”

Toshio Kuroki has expertise in identifying errors. In an interview last year with Retraction Watch, he talked about his discoveries about the question “How often do scientists who commit misconduct do it again?” He and colleague Akira Ukawa lavish more details about that in a paper of theirs called “Repeating probability of authors with retracted scientific publications.”

Brittany Fair joins Hair Club for Science Journalists (LFFFHCfSJ)

Brittany Fair has joined the Luxuriant Flowing, Former, or Facial Hair Club for Science Journalists (LFFFHCfSJ). She says:

(LFFFHCfSJ). She says:

You can call me Chewy. When not in Chewbacca form, my hair also enjoys styles such as Kelp Forest Mermaid, Princess Anna, and Legolas. Its utter independence is bewildering. Although, I do enjoy the surprise hairdo that accompanies each morning.

Brittany Fair, M.S., LFFFHCfSJ

Science Writer

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

La Jolla, California, USA

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers