Paula Vince's Blog: The Vince Review, page 6

October 8, 2024

'Pollyanna at Six Star Ranch' by Virginia May Moffitt

MY THOUGHTS:

I commend Virginia May Moffitt for choosing to do something that no other Pollyanna author did after Eleanor H Porter, and that is backtrack the story to Pollyanna's youth. Porter left no room to do so. Pollyanna 'grows up' in the second book of the series, and gets engaged at age 20 to her childhood chum, Jimmy. Ever since then, authors stick to her married life, although it was a shame to have passed over the scope for gladness in those teenage years. Moffitt evidently thought so too, because she decided to squeeze one in anyway.

Chronologically, this fits in at the halfway point of Pollyanna Grows Up. So you could stop reading that book at the end of Part 1, pick up this novel, then return to Part 2 when you finish. Here we have Pollyanna aged 16. She hasn't seen Jimmy since she was 14 and won't catch up with him again until she's 20. And Uncle Tom Chilton is resurrected from the dead for a few appearances, which is a bittersweet touch for us readers.

Having traveled for three years in Europe, Pollyanna and family are back in Beldingsville. Another young teen named Genevieve Hartley, whose father knows Uncle Tom, invites her to spend a few months at their ranch in Texas. Pollyanna will be joining Alice Jones for the train trip, a prim young school teacher who's returning to visit her Texan family. Uncle Tom is all for it, which neutralizes Aunt Polly's misgivings. So Pollyanna is off to spend time among the cactus and cowboys.

She has grown a little self-conscious about the Glad Game, since Alice hints that it's childish, but can't help telling people all about it anyway. And there are plenty of people to benefit, like Mrs Billings, the widowed owner of a nearby ranch who envies all the perks of civilization her daughter, Susie, is missing out on. There's also old Tarby, a former quick-draw cowboy who now considers himself a has-been; and young Jack Ainsley, an amateur or 'tenderfoot' who feels he has a lot to prove. And there's also Storm, a prickly wild girl with a log-sized chip on her shoulder, who needs a bit of taming; and a family of roving Mexican workers who could really do with some friends.

Okay, first for the good parts. It takes hard work by these characters to master the knack of the Glad Game, which gives us readers indirect lessons too. And Moffitt is great at embellishing her settings. Texas blooms beneath her pen; a spacious and breathtaking backdrop for honest and fun characters.

Alas, now for the bad. I find some key plot points are heavy-handed and way too predictable. Folk are searching for a long-lost heir who stands to inherit half of another neighboring ranch. I think Moffitt intended to stun us with a gob-smacking revelation, but it's obvious to any canny reader from a mile off who the unwitting heir will turn out to be. Far-fetched proof plummets down like missiles. If only somebody had tipped Moffitt off that her subtlety is of the sledge hammer type.

(She pulls the exact same move in the only other Glad book she authored, which was Pollyanna of Magic Valley. That long-lost heir's background and personality are similar to this one's. Using this tired trope once is corny, twice is almost farcical. So much for Virginia May Moffitt's contribution to this series.)

Pollyanna herself is far too good to be true this time around. She never once loses her cool, even when certain others behave in spiteful and dangerous ways. For this reason, I prefer Pollyanna's sidekick, Genevieve, who at least gets triggered as normal people do. Pollyanna's prattle about her Glad Game doesn't usually annoy me, but does in this story. There is some serious cheesiness overload. Pollyanna crosses a line to superior do-gooder, and white savior.

It irks me, for example, when Pollyanna assumes that Refugia, the young Mexican mother, presents a grubby appearance because she knows no better. Pollyanna instinctively tries to teach her how to wash her face and comb her hair, when it turns out that in fact, Refugia simply had no access to soap and a comb for weeks. Perhaps we 21st readers are primed to wince at a certain Anglo-centric condescension. I usually try to overlook it based on the age of a text, but it was hard in this case.

I really liked some of the characters, especially Genevieve, Jack (whose character is built up and then taken nowhere), and Alice's younger sister, Quentina. However, the drawbacks I've mentioned sadly prevent this from being a really good book.

🌟🌟🌟

Hooray, that's it, folks. I've finished reviewing every single one of the fourteen Glad Books. It's taken me longer than I anticipated, since those written by anyone other than Eleanor H Porter and Harriet Lummis Smith were lemons in their own way, making me loath to persevere. I guess the good news is that you only need to read the first six to get the best of the Pollyanna series. You can be GLAD of that, if you like. I might just hold onto Porter's and Smith's because I can't see myself ever re-reading any of the others again.

But hey, I'm glad I collected them all and extra glad that I've finished reading them. And if you're a completist, you'll no doubt want to do the same. Regardless of the quality of the stories themselves, I must say it is quite interesting to see how they evolve throughout the decades in which they were written, from the turn of the twentieth century and WW1 through the twenties, thirties (and WW2), forties and fifties. It's like a tour through the first half of the twentieth century.

Now, having received requests to review other books by Eleanor H Porter herself, I might start doing that before too long.

October 1, 2024

The Broad Scope of Fan Fiction

What is Fan Fiction?

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines it as 'stories involving popular fictional characters that are written by fans and often posted on the internet.' It is sometimes abbreviated to 'fanfic.'

I'd define it as a wealth of stories derived from other celebrated or well-known sources. When another author's work is used as a springboard for something new and original, that's fan fiction.

Why Do People Write Fan Fiction?

a) I'll start with the reason which may first spring to the minds of many. It is easier in some ways, to craft our writing to fit a worldview we're already familiar with, rather than creating a totally fresh world with brand new characters. When we and our potential readers already know and love a cast of familiar faces and their setting, we are free to dive straight into the action, because there is already a fan base.

Some fan fiction authors simply love the characters in pre-existing fictional worlds, feel they can't get enough of them and wish to add even more beyond the canon. Howard Pyle's 'The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood' fits this category. The legends of the heroic outlaw and his loyal band had been circulating since the Middle Ages when he decided to compile his own omnibus of stories in the late nineteenth century.

b) Sometimes authors feel triggered by an original canon. When source material seems sadly shortsighted or lacking, they may decide it needs to be threshed out, or even totally redressed. If something in a story presses our buttons, taking steps to set it right in our own way may be a pro-active move, or skillful literary protest. This may be by re-telling the tale from the point of view of another character.

A famous example is Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys' answer to Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. Rhys explores Edward Rochester's doomed first marriage from the point of view of Bertha, aka the mad wife in the attic. This fan fiction, now a classic itself, brings out Bertha's vulnerability, her powerlessness and lack of advocates to stand up for her.

Another revealing example is Longbourn by Jo Baker, who decided to re-tell the story of Pride & Prejudice from the servants' perspective. When events made famous by Jane Austen play out against the lives of the Bennet family's hired help, we readers get a chance to see familiar characters in a way we've never considered before.

A very recent example is Adventures of Mary Jane by Hope Jahren. This author is a great Mark Twain fan, yet the gullibility and passivity of the appealing character Mary Jane in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn galled her. Jahren explains in her introduction how she decided, 'We can fix this!' In her mind, Twain's version left much to be desired, which she deftly expanded upon without changing his canon. This includes making Mary Jane more intrepid by giving her a set of her own adventures.

c) Sometimes we may simply wish to draw from source material as a creative way of making some new social commentary or observation. Barbara Kingsolver's award-winning Demon Copperhead mirrors Charles Dickens' David Copperfield from start to finish. Using the framework of a famous Victorian classic to tell her own contemporary story about the deplorable foster care system and horrific opioid crisis in the Appalachian region of America is Kingsolver's ingenious way of suggesting that human nature hasn't changed.

Barbara Kingsolver certainly isn't the first author to have had the brainwave of adopting a well-established older story to mold her own take on it. The popular Broadway musical West Side Story is a mid-twentieth century re-telling of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, focusing on New York city's rival gangs. And speaking of Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew became Pygmalion which morphed into the musical, My Fair Lady, starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison. And not all that long ago, American author Anne Tyler did her own take on it in Vinegar Girl.

One of the most ambitious examples of all may be C.S. Lewis' re-telling of the Christian gospels as fantasy in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, with his majestic lion Aslan taking on the role of our Lord and Savior.

d) A fourth reason authors may decide to write fan fiction is to bring out more nuances or finer points from the original material which fellow fans may relish. Sometimes inspiration about book friends we all love and admire seem too good to keep to ourselves. This is the main reason why I decided to have a go.

I hope I've succeeded in showing that other important reasons for writing fan fiction exist than simple self-indulgence in prolonging our attachments to our favorite characters (although isn't the fun of that enough?) And I've hopefully proven that some quality, highly acclaimed examples may even fly under the radar of being fan fictions, although that is certainly what they are.

Introducing my own attempt.

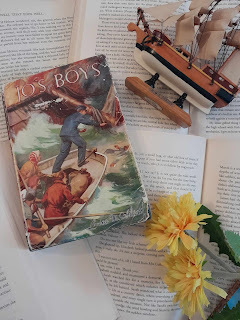

Two side characters from Louisa May Alcott's Little Women series have become main characters in a spin-off which I've shared on Archive of Our Own, an extensive site devoted to fan fiction. I always thought my two young men (for I now consider them mine) had huge potential, but Alcott was burned out by the time she wrote their incidents in Jo's Boys. She'd written just enough to capture my imagination, so this year I indulged my passion and developed their storylines into an all consuming project I named Longing For Home.

The first of these is Jo March's nephew, Emil, who follows his dream of going off to sea, but gets caught in a shipwreck. I've extended his couple of chapters from Jo's Boys to include a supporting cast of new characters, and a longer, slower burn of his romance with Mary, the captain's daughter. The other character is Nat Blake, a destitute former foundling who the Bhaers send overseas to study music. Nat is a talented violinist who battles anxiety and an inferiority complex from his impoverished background.

Giving these two young men voices of their own has been an extremely satisfying writing project, especially since I set out to stick within the parameters of canon. I resolved to weave in as much from Alcott's original source material as I could without ever deviating outside of the lines. I like to think Louisa May Alcott might have been happy with my result, because it's my tribute to her writing.

If I've stimulated your curiosity, please check out Longing for Home. You don't need to be familiar with Alcott's work to enjoy it. Archive of Our Own (AO3) is full of gifts such as this. Having spent time reading stories by many others before I ever dreamed of having a try, I now regard fan fiction authors as an extremely generous bunch of people who I'm happy to count myself among. For writing free novels and stories for fans to enjoy is surely a painstaking random act of kindness and labor of love.

And if you don't choose to commit to something so long at the moment, you might like to start with this shorter fan fiction I wrote. It's the perfect size to have with a cup of tea and slice of cake. And it features somebody we surely all know well.

Keep your eye out for my further upcoming posts about fan fiction. I will soon share some of my initial experiences about the fan fiction site, where I initially feared to tread but am now so glad that I did. It is a venue full of pseudonyms, and the one I've chosen (Ada Sage) is combination of my grandmother's given name plus the embodiment of wisdom, which also happens to rhyme with her maiden name, which was Ada Gage.

More later. (And by the way, every fan fiction I've mentioned in this blog post, I aim to review.)

September 24, 2024

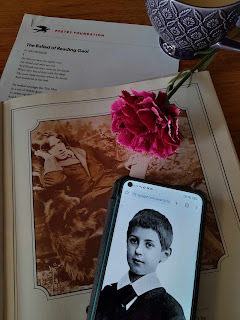

'Son of Oscar Wilde' by Vyvyan Holland

During my Diploma of Creative Writing, I studied an interesting subject named 'Literature and Christian Faith.' Each week we took turns reading aloud from some formative text, beginning from ancient times. One of our modern selections was Oscar Wilde's 'The Ballad of Reading Gaol.' It can hardly be called a tribute, but it was an acknowledgement of the shockingly hard two years he spent imprisoned there which contributed to his premature death. By writing this masterpiece after his release, Wilde's intent was to raise awareness of the barbaric British penal system and inhumanity of capital punishment. I was fascinated to come across this autobiography by Wilde's son, who was just a young boy when it all unfolded. It really shows how the ripple effect of one person's life may adversely shape those of others, putting in place the real life chain reaction nobody ever wants to start.

Also see my reviews of The Importance of Being Earnest and The Picture of Dorian Gray

MY THOUGHTS:

What a fascinating autobiography, and its scope even makes it something of a bildungsroman, but true instead of fictional.

Oscar Wilde's younger son, Vyvyan Holland, tells of his own baffled lifestyle as a child fugitive, following his famous father's imprisonment. Young Vyvyan (what a cool name, especially for the Victorian era) knows that his father, once feted is now hated, but his mother, Constance, conceals the details from him. So does Vyvyan's brother, Cyril, who accidentally discovers the truth but wishes to shield his little brother from the disgrace he feels.

Poor Constance Wilde, fearing harsh public backlash on her innocent sons, rushes them across to the Continent to hide. She changes their surname from Wilde to Holland, after some of her distant relatives. This story is an excellent literary social artifact about the lifestyle of boys in the late Victorian era, and what is expected of them as they become young men in the turn into the twentieth century and Edwardian era. Vyvyan writes differently from his dad, but his detailed memory, wry humour, and interesting incident choices kept me scrolling pages. I was finding that in no time flat, another hour had passed.

He describes the emotionally harmful burden of being forced to deny their father, compounded by their mother's sad, premature death a few years later, while they were still only 11 and 13. Cyril swings reactively to create an identity nothing like their father's, scorning anything he perceives as arty or effeminate. And Vyvyan himself develops a lifelong case of social anxiety and shyness, resulting from his fear and confusion early on. The two boys are hidden victims whose budding personalities are shaped by what happened to the previous generation. Being child pariahs takes a huge toll on them.

Next, Cyril and Vyvyan are left at the mercy of Constance's extended family; a straitlaced bunch who were always offended by Oscar's flamboyant notoriety and hadn't wanted her to marry him in the first place. Rather than seeing their new charges as a couple of vulnerable young boys, they perceive a pair of tinder boxes who might explode in outrageous ways at any time. The brothers are forced to keep the secret of their paternity until one day when Vyvyan is nearly 21, their father's friends discover their existence. To these new faces, the boys are more like holy grails who'd been long sought.

That's one of the lasting impressions this book leaves me with. Same pair of kids, but polar opposite sentiments, depending on others' points of view. It was one of the tragedies of the early 20th century that Oscar's zealous attempts to meet up with his sons after his release from prison were met with a brick wall. Vyvyan had no idea that his father was being told, 'The boys are happier without you in their lives,' since he certainly wasn't thriving with his reluctant guardians. In fact, Vyvyan was led to believe that Oscar was dead.

The publisher's note, in this book published in 1954, refers to Oscar Wilde's 'sexual perversion' and 'misguided way of life.' What would these early readers think, and what would Vyvyan himself think, to see how far the social tide has turned!

Vyvyan is not afraid to call out the worst of Victorian hypocrisy, including the cruelty of some highly acclaimed folk of the time period. I fully agree when he says toward the end:

'I do not try to defend my father's behaviour but I do think that the penalties inflicted upon him were unnecessarily severe. And by that I do not only mean the prison sentence, I mean the virtual suppression of all his works and the ostracism and insults which he had to endure during the remaining years of his life.'

However, I disagree with these words written by Vyvyan in his Preface.

'This is not a very amusing and entertaining story. I think, however that it should be written as part of the whole story of Oscar Wilde.'

He sells himself short there, because in spite of plenty of reflective and serious subject matter, I did find this book on the whole, especially some of the antics he and Cyril get up to, to be vastly amusing and entertaining indeed. I'm sure it'll be up among my ten best books of the year.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

September 17, 2024

'Carry On, Mr Bowditch' by Jean Lee Latham

MY THOUGHTS:

I've seen this Newbery Award winner from 1956 being recommended by decades of readers, including homeschoolers. I finally discovered I could borrow an internet archive copy. It's a fictionalized biography of Nathaniel Bowditch, the young mathematician and astronomer who noticed a dire need for a comprehensive, potentially life-saving encyclopedia of navigation, so went ahead and wrote one.

Instead of fulfilling his dream to become a Harvard graduate, young Nat (born in 1773) is shaped by the school of hard knocks. Family hardship requires him to help in his father's cooperage business, and then he's indentured as a clerk in a chandlery. During his early twenties, Nat Bowditch sails on several merchant ships and discovers, to his horror, that Moore's Navigation, the standard resource for seafarers, is riddled with errors.

Young Nat gets hopping mad. 'It's criminal to have mistakes in a book like this. Men's lives depend on the accuracy of the tables! When you depend on a book with mistakes, it would be safer not to depend on it.' His only viable solution is to replace it by writing a huge tome of his own, and luckily for all sailors, Nat has the brainpower to pull it off. It's a monumental feat for a young, self-taught man, which deserves far more acclaim than he possibly gets in the 21st century.

Nat Bowditch also educates other crew members in navigation, and eventually becomes a captain himself.

There is a lot to wrap our heads around. I won't even begin to delve into the historical backdrop, with America's War for Independence followed by the Napoleonic Wars, even though they're fascinating in the context of Nat's life. (Suffice to say that having won that first war, America must fight for her rights on the High Sea, which makes British vessels look like ultimate sore losers.) Rather than letting this review blow out into something huge, I'll list off the main points that struck me.

1) Who needs Harvard! Not highly motivated geniuses anyway. Study is what teenage Nat does in his downtime for fun. He teaches himself Latin so that he can understand 'Principia' by Isaac Newton. Interesting that we modern folk consider Latin to be a dead language, yet in the late 18th century it was the cutting edge language of scholars and scientists. Who killed it? Next, he teaches himself French, Spanish, and German too.

2) Bowditch's life was incredibly tragic. Sure, this novel condenses it within 300 or so pages, but there is so often a fresh announcement of some heartbreaking death. The line, 'I'm sorry to tell you, Nat, I have some very bad news,' becomes a major motif. His second young wife, Polly Ingersoll, must have been reckless to have married him, having seen firsthand what happens to people Nathaniel Bowditch grows fond of. I see that several other reviewers decided to give this novel less than five stars solely because of all the deaths. I understand their decision, even though it's not Latham's fault. She didn't make all this crazy, sad stuff up. Maybe giving her book a lower ranking is a case of, 'Don't shoot the messenger,' yet it's still problematic having a book aimed at juvenile readers which a huge percentage of them may be too sensitive to read.

3) I appreciate Nat Bowditch's acquired patience. One of his love interests points out that his brain works so fast, he 'stumbles over other people's dumbness.' Eventually Nat makes a point of noticing the exact moment when the people he tutors twig, so that he can write his 'dumbed-down' explanations in his notebook, for they must be the most effective teaching tools. I always imagined it must be cool to be a genius, but they evidently suffer the downside of finding 99% of people have puny mental scopes, compared to their own. Small talk must get tedious.

4) I was awed by the brilliance and dedication of Jean Lee Latham herself, for she obviously put everything she had into writing this book. The flyleaf of the version I borrowed tells us that before making a start on the story, she studied Mathematics, Astronomy, Oceanography and Seamanship to familiarize herself with Bowditch's work. Wow, that takes fandom to a whole new level, and it shows in the story. I didn't miss noticing the painstaking detail.

On the strength of that, I wish I could give this book 5 stars myself, but nope. Along with all the deaths, I thought Latham compresses so much detail and time frame within a comparatively short word count, it gets a bit bogged down at times. It's almost enough to blow the brain gaskets of readers who aren't as cluey as either Nathaniel Bowditch or herself.

Still, I've got to say it definitely encourages us to smarten up our own work ethics. Sure we might never be able to write major scientific encyclopedias or even the bios of those who do, yet we can devote ourselves to the projects which ignite our imaginations and seem worthy, even when the going gets tough. One of my favourite lines in the story is when teenage Nat learns Latin with the intent to read Isaac Newton. He says, 'First I have to figure out what it means in English, and then I have to figure out what it means.'

I'm inspired by such painstaking and compelling enthusiasm.

🌟🌟🌟½

September 10, 2024

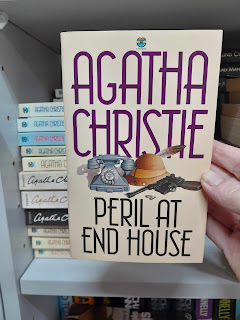

'Peril at End House' by Agatha Christie

Hercule Poirot is vacationing on the Cornish coast when he meets Nick Buckley. Nick is the young and reckless mistress of End House, an imposing structure perched on the rocky cliffs of St. Loo.

Poirot quickly takes a particular interest in the young woman. Recently, she has narrowly escaped a series of life-threatening accidents. Something tells the Belgian sleuth that these so-called accidents are more than just mere coincidences or a spate of bad luck. Something like a bullet! It seems all too clear to him that someone is trying to do away with poor Nick, but who? And, what is the motive? In his quest for answers, Poirot must delve into the dark history of End House. The deeper he gets into his investigation, the more certain he is that the killer will soon strike again. And, this time, Nick may not escape with her life.

MY THOUGHTS:

We're back with Poirot at his most egotistical, never missing a chance to sing his own praises.

The story is narrated by his sidekick, Captain Hastings. The pair of them are staying at the Majestic Hotel in the Cornish seaside town of St. Loo. Poirot is adamant that he wants to retire from private investigation, yet even as he speaks, a furtive bullet is fired at a pretty girl who strolls past their verandah. She informs them it's the fourth time she's experienced a near miss within a short period of time. The young lady is Miss Nick Buckley, the owner of the ramshackle End House, which stands alone on a promontory overlooking the sea. Her plight is enough to entice Poirot to re-think his decision.

Who could possibly want to kill this charming and bubbly young woman, whose property is worth nothing substantial? Poirot is certain that whatever the motive, it must be deeply hidden or else the crook wouldn't take such brazen risks in broad daylight.

There are Australian characters in this book; a middle aged husband and wife duo named Bert and Milly Croft, who rent a small lodge on Nick's property. The bunging on of their Aussie colloquialisms is cringeworthy. Bert refers to Poirot as a 'bonza detective,' and says, 'I think neighbours should be matey, don't you?' And he always summons his invalid wife with a 'Cooee.' Even Poirot muses that they might be just a shade too typical for their culture. So the question becomes whether Agatha Christie is making them so overdrawn for a reason. I certainly hoped so, because that's easier to swallow than so many other international authors who overdo our Aussie persona accidentally.

Poirot often refers to Hastings' 'slightly mediocre mind,' which irritates but never outright offends his best friend, since they know each other too well. At one stage, Poirot chastises himself, asking, 'What good is it to be Hercule Poirot, with grey cells of a finer quality than other people's, if you don't manage to do what ordinary people cannot?' And Hastings simply reflects, with an inner eye roll, 'Poirot's self-abasement is astonishingly like other people's conceit.'

There's another amusing incident in which Hastings lists Poirot's OCD qualities, such as toast that has to be made from square loaves, eggs matching in size and his objection to golf as a shapeless and haphazard game.

My biggest problem with this mystery is that I sadly figured out the villain around the halfway point! Yep, for once I guessed the criminal and their motive before the brilliant Hercule Poirot twigged. Maybe Dame Agatha was too heavy-handed with her clues this time. Or perhaps I need to have an even longer break between reading her books. It's hard to say. It took the wind out of my sails when I noticed a glaring red flag. I prefer it by far when I don't guess, or at least not so easily, because unlike Poirot, my grey matter is not such fine calibre, so I look forward to the satisfaction of being surprised. Because I wasn't this time, and also because of the annoying Croft couple and Poirot being irritatingly smug, this one is not a three star read for me.

Dame Agatha has the occasional misses. To me, this is one of them.

🌟🌟

September 3, 2024

'Longbourn' by Jo Baker

Having just finished writing a fan fiction of my own, I thought I'd like to read more fan fiction by others.

MY THOUGHTS:

The titular setting is the legendary home in Pride and Prejudice where two radically different lifestyles orbit along together. The mismatched Bennet parents and their five daughters are, of course, well known by generations of readers. Jo Baker now decides to reveal the tale of their servants, who deal with the unmentionable but vital aspects of keeping life functioning smoothly. These five know full well that their security depends upon the caprice of their employers.

Baker's author blurb informs us that her own forebears had been employed in service, so she knows full well that instead of attending the Netherfield ball she would have stayed home with the washing up. My ancestry is equally humble, so I found this story to be revealing and significant from the get go.

Our main character is a young housemaid named Sarah, who works under Mrs and Mr Hill, the housekeeper, and butler. There is also Polly, a pert adolescent maid who is learning on the job. One day the Bennets hire a new young footman named James, who Sarah suspects of concealing some secret. It turns out James has far more to hide than he's even aware of himself.

Meanwhile, Sarah's fascination is stirred by a freed slave turned servant named Ptolemy, who works on Mr Bingley's estate. She's attracted to Tol's sprightliness and the wider world he represents, yet something about the mysterious and evasive behavior of James also intrigues her. I love how this romance, in all it's everyday, sometimes sordid routine, plays out against that more famous plot that we all know so well.

The Bennets, their neighbors and all other familiar characters are totally true to canon, yet we're offered deeper, richer ways of understanding them, since we now see them as their underlings do. For example, it takes an insightful helper like Sarah to sense that Elizabeth's new married life isn't totally angst free, as she adjusts to the expectations of being mistress of such an intimidating address as Pemberley.

After forming my own thoughts, I turned to other reviews, expecting a bit of flak, for Jane Austen's most devoted fans tend to deify her and consider her work untouchable. Yet I was stunned nonetheless by the sheer volume of cutting and unkind reviews of one and two stars on Goodreads. Holy moly! I guess Jo Baker must've known she was prodding a sacred cow. What amazed me most was the vitriolic content of some of these reviews, because these reactive people might've been reading a totally different book to me!

Some called it humorless compared to the great Jane Austen, yet to me it brimmed with wry observations that kept me grinning. How ironic that the same people who complain of no humour evidently take Pride and Prejudice extremely seriously.

Others call Sarah a whinger, yet I considered her to be wise, astute, and far more gracious than some of those big-nobs deserved. I suspect some of the disgruntled readers resent Sarah's insights into sides of their favourite characters they refuse to acknowledge. Apparently suggesting that Darcy comes across as a granite block in the eyes of the working class, or that Lizzy is somewhat preoccupied and insensitive to her servant's priorities is a crime to some. And heaven forbid that anyone should feel sympathy for Collins (that easy-to-please young man) or Lydia (merely a child seduced by a master manipulator).

Come on peeps, Pride and Prejudice is a novel, not a sacred text! Please don't be so blinkered about the sanctity of your favourite characters that you resist an opportunity to see how they may come across to others! I suspect those who do so might be the sort of readers who also resist real life revelations about themselves. This book is a refreshing invitation to expand our outlooks, and it's sad to see that so many diehard Janeites refuse to take it as such.

Some reviewers object to the TMI (too much information) factor in passages such as this.

'The young ladies might behave like they were smooth and sealed as alabaster statues underneath their clothes, but then they would drop their soiled shifts on the bedchamber floor to be whisked away and cleansed, and would thus reveal themselves to be the frail, leaking, forked bodily creatures they really were. Perhaps that was why they spoke instructions at her over an embroidery hoop or over the top of a book: she had scrubbed away their sweat, their stains, their monthly blood; she knew they weren't as rarified as angels and so they just couldn't look her in the eye.'

I get that this sort of straight talk isn't everyone's jam. Since this particular description occurs on the second page of the story, it's an early invitation for the squeamish to instantly abandon the book rather than read the whole thing and then slam it. I think stark realism like this is handy for revealing the disingenuous quality of the nineteenth century when facts of life were routinely swept beneath the carpet.

One particular plot twist (which I can't spoil here) inevitably causes some readers' hackles to rise. They insist, 'It's because Jane Austen herself didn't write it in.' Hmm, perhaps she simply didn't know about it. Even I object to the type of fan fiction that contradicts and changes canon, but Longbourn doesn't do this. The skeleton in the closet which I'm skirting around is consistent with Austen's unfolding of events. Baker never once destroys the Pride and Prejudice canvas, but merely offers us a broader vista from which to view it.

So after my rant about the ranters, my final verdict is that I loved this story for its boldness and its beautiful imagery. As far as Pride and Prejudice spin-offs go, it's a winner in my opinion. Now, some reckless soul should write a novel depicting Wickham as the put-upon and misunderstood young man he presented himself as being. Not because I admire him, which I certainly don't, but because it would be interesting to watch the fur and feathers fly.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

August 27, 2024

'Emil and the Three Twins' by Erich Kastner

Emil and the three twins. Three Twins Yes, you read that correctly. Emil Tischbein has another adventure with his old friends the Professor, Gustav and Little Tuesday - this time by the sea. Of course, the detectives couldn't have an ordinary seaside holiday like other people - and when they become entangled with the mystery of the three acrobat twins and the wicked Herr Anders, it looks as if it's going to turn into a most extraordinary time for them all!

MY THOUGHTS:

This is a quirky plot to match its quirky, self-contradictory title. It's clear this story will be slightly left of field from the moment Kastner gives two illustrated prefaces - one for readers of Emil and the Detectives and the other for fresh readers. He informs us former that Emil is 'still content to be the same excellent young fellow,' hoping to earn enough money so his mother can quit working. But this time, Kastner introduces a spanner in the works.

Sergeant Jeschke, now P.I. Jeschke, asks for Emil's blessing to propose to his mother. The sudden prospect of a new stepfather is a real curveball for Emil, who isn't okay with the idea, but generously hates to make waves. It takes some sage perspective from his wise grandmother for Emil's headspace to catch up with his outer compliance. (I love how she counsels Emil to consider his thumbs-up as an investment into his beloved mother's future, for ten years down the track, Emil may get married, and a young wife plus a middle-aged mother don't mix well beneath the same roof. She says she's tried both positions over the years, and knows. Therefore, holding his peace is essentially an investment into Emil's own future too.)

Meanwhile, Emil, Gustav, little Tuesday and Cousin Pony have all been invited to spend part of their summer holidays at the Professor's parents' beach house. At the seaside town, they come across the Three Byrons, a trio of circus acrobats comprising a father and two sons. The boys decide to make a charitable protest when the rumor reaches them that Dad Byron intends to cast off young Jackie, who is growing far bigger and bulkier than his brother, Mackie, because it's affecting their act.

I enjoy reading about these German lads from the 1930s discussing philosophers such as Goethe. They expound on whether nature really endows all children with enough raw material to bloom like cabbage roses, or whether outside intervention from educational institutions is necessary to draw it out of them. During our homeschooling years, I used to come across both points of view, loud and clear. Perhaps Herr Haberland, the Professor's father, expresses best why the waters are still so murky.

'It's confoundedly hard training children either too much or too little, and the problem is different with every child. One develops his inherent abilities smoothly and another has to have them dragged out of him with a pair of forceps or they'd never come to light at all.'

Hear hear, every homeschooling philosopher who pushes one particular method ought to take the message of this simple paragraph on board.

Another highlight is seeing Grandmother and her two grandkids, Emil and Pony, view the sea for the first time. Cosmopolitan Pony sees it as, 'An invisible shop assistant unrolling bright silk on an endless counter.' Although the boys all laugh her down, I like her analogy.

It's interesting how characters show up the attitudes and habits of their times. For example, Emil throws his sandwich wrapping out of the train window, to watch it blow against the shrubs along the track. Now this boy is super conscientious in all respects, so his action here indicates that being a litterbug simply wasn't a thing in the 1930s. Nobody ever gave it a passing thought.

Some advice still holds true. One of Kastner's personal hobbies is to catch public transport to unfamiliar locations in his own city and just walk around. It sounds like a cheap and doable creativity and productivity hack for the 1930s and the 2020s alike.

Overall, I consider this to be another gem from almost a century ago which should be more widely read by the age group who was its target audience back in its day.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

August 20, 2024

'Pollyanna and the Secret Mission' by Elizabeth Borton

MY THOUGHTS:

This is the final novel in the chronicles of Pollyanna's married life. She and Jimmy are empty-nesters about to commence a second-honeymoon phase of their lives, for Junior and Judy are both married and Ruth is off to college. Pollyanna is about to accompany Jimmy to Mexico in his roving job as a freelance consulting engineer. He's been hired by the Mexican government for some water storage and reclamation projects. Meanwhile Pollyanna is glad to catch up with their old friends, the Morenos.

I expected the title would refer to some heartfelt, meddlesome project of Pollyanna's own devising, but I was wrong. Instead, we're thrown into top secret, espionage, FBI sort of business, and even the Pendletons don't realize what's going on. It reminds me of the old, 'Get Smart' sitcom, because the post-war era feels similar. The 'secret mission' doesn't come to light until way near the end of the book.

The 1951 publication date is evident all through, in recipes, household tips and outdated attitudes. Judy proudly serves her mother a jellied salad, a retro dish indeed. And when Judy's husband, Ron, starts washing the dishes, his wife and mother-in-law 'stop to giggle, as they realize what a pampered and superior feeling it gives women to hear a well-meaning man blunder around in the feminine world!' I think Borton considers herself forward thinking, but such lines indicates she's a product of her decade.

This time around, she hasn't done too bad a job of picking up threads other authors have left dangling for her. Pollyanna's son-in-law, Ronald Keith, was Margaret Piper Chalmers' brainchild, but Borton expands his character with some interesting developments. But sadly, the plot is a bit convoluted with characters that are difficult to feel empathy for.

Newcomers in this story include Anna Robesky, a graceful young blonde who claims to be writing a novel; Santiago Leal, a talented but abrasive scuptor; and Dr Silvia Godinez, a clever but dowdy academic. We also have Margie and Jessie, a pair of young cousins who work in beauty parlors and try hard to convince clients to consider nail extensions. And there is Jimmy's assistant, a young Irishman named Johnny Murphy, along with a grown-up Anita Moreno, who was a little girl like Ruth in Pollyanna's Castle in Mexico. If any of these characters spell danger, accidentally or otherwise, the Pendletons had best beware, for stakes are a lot higher than we find in other Glad Books.

Overall, it's been like a game of Chinese Whisper between these authors. A broad view may appear seamless to some readers, but taking a step back reveals that in some controversial matters, Pollyanna's attitude has taken a total U-turn. Like the frog in the boiling pot, the heat may have been increased slowly enough that over time, many readers may not have noticed.

For example, Borton's Pollyanna tells her daughter, Ruth, that she wants her to have a solid profession behind her before she ever thinks of marriage. This totally contradicts Harriet Lummis Smith's Pollyanna, who was a blinkered advocate for stay-at-home moms to the extent of locking horns with Mildred Richards, the gift-shop proprietor in Pollyanna's Jewels. Although Borton's Pollyanna gives lip service to changing times, I tend to think it's more to do with two separate authors having opposing viewpoints on a hot topic.

Borton puts this speech in the mouth of another character, Dr Urbina.

'Any life which applies rigid restrictions on a woman's natural interest in new things and processes dulls her mind. Women are sensitive enough to resist this. The first years of marriage usually do nothing but accustom a woman to living in a restricted field. Her general interest in people must now be confined to one man. Her life is circumscribed by four walls. She conforms to letting her husband put more and more chains on her and narrow her activities more and more to attentions to a few persons, with himself as hub and a few family members and friends as spokes of the wheel. The bride accepts all this because she is in love... but when the lustre wears off and she finds herself enclosed within a narrow sphere of repetitive duties, and of association almost entirely with young children, it is too late to strike out for any change from her routine.'

Although Borton's Pollyanna is first to cheer this sentiment, Smith's Pollyanna would have heatedly replied that the home canvas is broader and full of far more novelty than many people give it credit for, and that those precious years with kids are fleeting and deserve total focus. I can't help wondering if Borton knew she was undermining Smith and set out intending to do just that.

Sadly, extended family still don't get a mention. Anyone wondering whatever became of Aunt Polly, Uncle John and Aunt Ruth, Sadie and Jamie, will be disappointed. I can't help thinking the latter Glad Book authors have let down their fans by not at least giving a few lines of closure for these folk who played such huge roles in Pollyanna's and Jimmy's lives.

I do agree with Borton on one thing. She points out in her Foreword that the Pollyanna philosophy has wrongly been labelled 'false optimism' by people who haven't bothered to ponder its meaning. Hear hear! Nothing has changed, Borton. The 21st century is full of modern, self-proclaimed experts who use the very name of Pollyanna as an insult for desperate and deluded minds who practice what we now call 'toxic positivity.' They obviously haven't read the books, or they'd know Pollyanna does no such thing.

🌟🌟🌟

Last up will be Pollyanna at Six Star Ranch, which is a flashback to Pollyanna's youth, a time period compressed by Eleanor H. Porter herself, in Pollyanna Grows Up.

August 14, 2024

'Magic for Marigold' by Lucy Maud Montgomery

The eccentric Lesley family could not agree on what to name Lorraine's new baby girl even after four months. Lorraine secretly liked the name Marigold, but who would ever agree to such a fanciful name as that? When the baby falls ill and gentle Dr. M. Woodruff Richards saves her life, the family decides to name the child after the good doctor. But a girl named Woodruff? How fortunate that Dr. Richards's seldom-used first name turns out to be . . . Marigold! A child with such an unusual name is destined for adventure. It all begins the day Marigold meets a girl in a beautiful green dress who claims to be a real-life princess. . . .

MY THOUGHTS:

A well-written Montgomery novel is always a pleasure to read, although this one starts off sadly. The baby heroine's father dies two weeks before her birth, her mother has barely recovered from her grief, and the clan gathers together to choose her name. As little Marigold grows up in her dead father's family nest, she brings much-needed sunshine and the story takes her to the cusp of adolescence in a series of the type of episode Montgomery writes so well.

In some ways, Marigold is a girl after my own heart, and in others she drives me nuts!

Marigold's overriding trait is her innate belief that the world is a very 'int'resting' place, and she makes magic for herself with her thoughts and daydreams. It's a purely private skill since she often keeps quiet about what she mulls over, and thanks God for 'arranging it so that nobody knows what I think.' As a fellow secretive daydreamer from way back, I find Marigold more relatable than the far more sociable Anne Shirley, who bubbles out whatever she thinks to anyone within earshot.

Life draws thoughts from Marigold which she's probably wise to conceal. She's bitterly jealous of the portrait of Clementine, her father's first wife, who was regarded as far more of a beauty than Marigold's mother. Marigold also has a pretend friend named Sylvia, who she senses is just a trifle too weird for most of her 'real' friends to wrap their heads around. And she throws an inner tantrum when she hears the rumour that her mother might marry the new minister, Mr Thompson.

I can't help thinking in this instance, Marigold realises her attitude stinks. Loyalty to her dad surely can't be such a big factor, since he died before her birth. She just doesn't want her own little bubble to burst, and luckily for her, it doesn't. Yet I suspect Marigold would have caused a huge hassle for her poor mother if her worst fears had materialised. Judging by her extreme reaction when her grandma takes away the keys allowing her to 'visit' Sylvia, Marigold lacks the flexibility to take life's blows in her stride.

(Honestly, who the heck languishes with grief to the point of death because they can't visit a pretend friend on the turf they've chosen? Even I found that overdrawn, and I was an intense, imaginative kid too. But unsurprisingly, the answer is the same person who resents the prospect of their mother finding renewed happiness with another man.)

But even though she's extremely manipulative in her passive-aggressive way, another thing that makes me sympathise with Marigold overall is her tendency to be a follower rather than a leader when it comes to her real life friends. Even though she has originality and imagination, she lacks the forcefulness to push herself forward, but that's okay. We can't all be chiefs, yet we can follow Marigold's example and stick up for ourselves when pushed too far. She shows we can have an agreeable nature without being a pushover.

I like the string of droll, larger-than-life playmates who stream through Marigold's life and the funny ways in which her hang-ups tend to get resolved.

Supporting adult characters are good. Marigold's mother, Lorraine, verges on the meek and downtrodden side, yet living as her stern mother-in-law's righthand man can't be easy without the solace of her husband's support. Notwithstanding, Lorraine does a fine job of parenting Marigold, suggesting that 'good enough' under challenging circumstances really does hit the mark.

Now, I don't consider myself a die-hard feminist, but I was miffed by the unspoken rule we see that women of the 1920s may occupy just one sphere at a time. Aunt Marigold begins the book as a brilliant doctor who saves at least one life while her medical peers remain baffled. Then when she marries Uncle Klon, it appears she must give it all up. What a waste of training and talent, potentially impacting many others apart from just herself. Thanks heavens we live a century later when the same woman can be a doctor as well as a wife and mother.

This is probably my biggest bugbear of the whole book. I understand that a woman's role as family anchor was treated with great respect, and I always jump to Anne Blythe's defense when people slam her for becoming 'just a housewife' instead of pursuing some idealistic literary career. But gee whiz, Uncle Klon and Aunt Marigold don't even have any kids! And she'd already put herself through medical school and set up a practice. Does she now devote the rest of her life to stroking his brow and folding his socks?

I feel as if this book ends on a good note, just as 12-year-old Marigold is on the threshold of exploring new feelings, regarding a particular boy. If Montgomery had followed this stand-alone book with another story about Marigold's teen years and young womanhood, I would have gone straight onto that next.

As it is, this was a fun read. There's a lot to love about being transported back to an old world where rudimentary motor cars rumble alongside horse drawn buggies, every household hangs a photo of Queen Victoria on their wall, cake must always be on hand in case of unexpected guests, and fruitcake is stored in an airtight box beneath the spare room bed. Duties and responsibilities seem refreshingly slower-paced, yet we readers can sense the possible threat of tuberculosis hanging over each and every family. Reading this book encourages us to adopt the best of this 1920s era if we want to, without having to factor in the worst of it.

🌟🌟🌟🌟

August 7, 2024

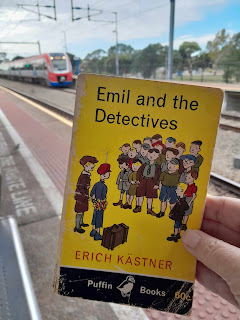

'Emil and the Detectives' by Erich Kastner

If Mrs Tischbein had known the amazing adventures her son Emil would have in Berlin, she'd never have let him go.

Unfortunately, when his seven pounds goes missing on the train, Emil is determined to get it back - and when he teams up with the detectives he meets in Berlin, it's just the start of a marvellous money-retrieving adventure . . .

A classic and influential story, Emil and the Detectives remains an enthralling read.

MY THOUGHTS:

This is quite a cool little tale in which the main character is both victim and detective.

The book was on our shelves for years when I was little, yet I shunned it, assuming it to be a 'boys' book' purchased for my brother. In more recent years I've noticed it being celebrated as a kids' classic, and early juvenile detective story, being published in 1929. It seems the young target audience in Germany couldn't get enough of Emil, so his fame spread to the English speaking world.

At the outset, we're told that our conscientious young hero, Emil Tischbein, is 'not a prig' since he has to make a concerted effort to be good, just as some people try to give up indulging in sweets or going too often to the pictures. (And we 21st century readers may add social media addiction.) This transparency and thoughtfulness makes young Emil instantly likeable. He understands his mother's ongoing costs-of-living worries and is willing to do his bit to help.

So 10-year-old Emil lives with his widowed mother who struggles to make ends meet as a hairdresser. One day he embarks on a train journey to visit his grandmother, aunt, uncle, and cousin in the big city of Berlin. His mother sends some hard-earned cash for Grandmother, which Emil pins to the inside of his jacket pocket, anxious not to lose it. In spite of all his precautions, the train's motion lulls him to sleep and Emil wakes up to discover he's been robbed.

He has a fair idea who the thief is. The sleazy Herr Grundeis who shares his carriage seems the type of man who would sink low enough to rob a young boy snoozing on a train. Hardly knowing what recourse he ought to take, Emil hops off the train several stations too early to trail the scoundrel, lugging his suitcase and a colorful bouquet, also from his mother to his grandmother. These have become iconic props of the story, which I believe represent different aspects of Emil's character. The suitcase indicates his unfamiliarity with the overwhelming cosmopolitan environment, while the flowers signify his love and loyalty to family.

Emil enlists the help of some lively, unlikely comrades to help catch the thief. They are several city boys his own age who consider themselves to be running their own, thrown-together detective agency. And the author, Kastner, cleverly weaves himself into the story down the track.

When Emil's city family find out what's happening, his girl cousin, Pony Hutchen, comes to help. Some modern readers may think Pony's input dates the story as anti-feminist, since she proudly offers to look after the boys with coffee and rolls. However, I'd never classify Pony as a willing drudge. For starters, she's wise and resourceful, also doing plenty of other cool stuff such as speeding around on her bicycle and giving sage advice. And the hospitality/care role she takes upon herself undeniably makes everyone's lives far easier and more pleasant, so taking offence on Pony's behalf from our enlightened stance may be levelling uncalled for criticism at a worthy industry. She doesn't have a servant mentality. Rather, she has wisdom and forethought.

The simple theme is to never underestimate kid savvy and strength in numbers. Proving the crime turns out to be an ingenious brain wave on Emil's part. Altogether, it's a fun story, hugely action driven and fast-paced. If kids their age ever really had the freedom to go racing around all over the city, I think stranger danger became more of a thing in later decades.

It's not really a detective story as such, since everyone knows full well who the villain is. It's more of a high-speed chase.

An underlying theme is the value of money, and sad chasms between the rich and poor. Nothing much has changed. Here's a bit of dialogue between Emil and one of his new friends, a boy who's dubbed, 'the Professor.'

Emil: Are your people well off?

Professor: I don't really know. Nobody ever talks about money.

Emil: Then I expect you have plenty.

I followed this up by watching the film of the same name from the 1960s, which adds a huge number of changes to make it even more dramatic, one of my pet eyerolls.

🌟🌟🌟½

I'll soon follow up this review with its sequel, Emil and the Three Twins.

The Vince Review

I invite you to treat this blog like a book-finder. People often ask the question, "What should I read next?" I've done it myself. I try to read widely, so hopefully you will find something that will strike a chord with you. The impressions that good books make deserve to be shared.

I read contemporary, historical and fantasy genres. You'll find plenty of Christian books, but also some good ones from the wider market. I also read a bit of non-fiction to fill that gap between fiction, when I don't want to get straight on with a new story as the characters of the last are still playing so vividly in my head. ...more

- Paula Vince's profile

- 108 followers