Paula Vince's Blog: The Vince Review, page 3

May 6, 2025

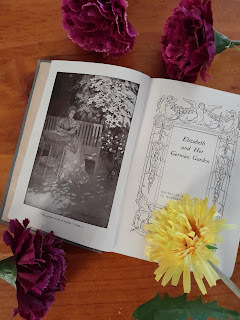

'Elizabeth and her German Garden' by Elizabeth Von Arnim

I discovered this vintage hardcover at a secondhand shop. I wasn't enchanted by The Enchanted April, Von Arnim's runaway bestseller from 1922, but thought this earlier title from 1898 might hit the spot.

MY THOUGHTS:

Here is a lovely vintage book for the introvert population written in a series of diary entries.

It is the late nineteenth century. Elizabeth is a young aristocratic woman whose passion project is working in the extensive garden of their secluded country manor. After years of trying to fit in with the world she sees around her, she's astounded to find that a quiet lifestyle puttering away at home, far from the social climbing and drama, suits her to a tee. Now Elizabeth's only aim is to make up for precious time she lost when she kowtowed to the expectations of others, tried to put on an impressive face and cared what people thought of her.

Brushes with others involve assuring them that she is genuinely happy tucked away, for human nature being what it is, they insist in believing that her lifestyle must be desolate and grim for her, since it would be for them.

However, certain times of the year bring inevitable house guests. During the time period this book covers, Elizabeth finds herself hostess to two other young women. One is Irais, another burned out wife of society whose wit tends to be cynical. Even though Elizabeth likes her a lot, anyone's company tends to be draining in long doses. The other guest is Minora, a simplistic girl who aims to write a book of impressions without a clue that her observations tend to be of the skimming, shallow type. Elizabeth records her own experiments of standing back and letting Irais and Minora clash.

Elizabeth has three little daughters; the April baby, the May baby, and the June baby. She also has a supercilious husband who she calls the Man of Wrath, and never gives the impression that she's madly in love with him, although there are certainly worse fellows to be found. He reveals himself as a chauvinistic grouch who considers himself a philosopher and remarks that women never speak a word worth listening to, as far as he's ever heard. With the wonderful influence of her restorative garden, Elizabeth doesn't let the Man of Wrath get her down. She's strong enough in herself not to let him.

'What a happy woman I am living in a garden, with books, babies, birds, and flowers, and plenty of leisure to enjoy them! Yet my town acquaintances look upon it as imprisonment and burying, and I don't know what besides. Sometimes I feel as if I were blest above all my fellows in being able to find my happiness so easily.'

That's my main takeaway from this book. Elizabeth, whose philosophy is far wiser and easier to swallow than her husband's, thrives with the same simple resources at her fingertips as those available to me. She doesn't aim to extend her reach, become any smarter, or embark on any self-improvement program. After several tiring years, she's decided she has nothing to prove. She's one of those refreshing people whose thoughts serve as course corrections, if we're willing for them to be.

Here's to books, flowers, bird song, cats, hot drinks, leisurely walks, and many other good things.

🌟🌟🌟🌟½

April 29, 2025

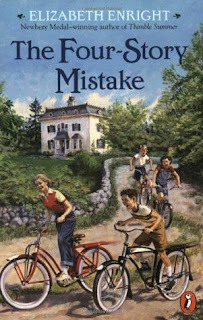

'The Four-Story Mistake' by Elizabeth Enright

Note: I bought a kindle version of this second installment of the Melendy Quartet, but searched around for my favorite cover. I think this Puffin edition from 1997 nails it! The four of them look the perfect image of how I'd imagined them. That took love and care from the artists. A big thumbs up from me.

MY THOUGHTS:

This second book in the Melendy Quartet is as delightful as The Saturdays, which preceded it.

The Melendy family relocate from their city home to a droll old house in the country with three storeys and a strange, dome shaped cupola perched on top. There's a sense that Father's catalyst for the move was the furnace incident followed by the attic fire in the first book. Although Randy is initially sentimental about leaving the city, she and the others soon discover that the new residence has even more to recommend it for energetic souls such as themselves, including a brook, summer house, and two iron deer.

The foursome soon discover a mystery to solve. Why is there a boarded up room off their common room, with a life sized portrait of a girl named Clarinda? Who was she?

There's more of a sense of WW2 playing out in the background than there was in the first book. The Melendy kids aspire to save up for Victory Bonds to be patriotic and help the soldiers. Since the elder pair are now into their teens, they find ways of earning regular incomes. Mona gets a gig acting in a radio show (which she adores). Then Rush taps into a local demand for anybody who might be able to teach piano lessons (which he abhors at first). And Randy makes an unexpected discovery that enables her to contribute her bit too.

Overall, home is comprised of the loved ones who fill it. Their wise and understanding father provides a solid anchor, even though his line of work means he breezes in and out. Good old Cuffy, as always, is totally invested in them and more like a doting grandma than a housekeeper. Willy Sloper goes along too, with a promotion from furnace man to field hand. Presumably Father must have made him an offer he couldn't refuse.

I loved this trip into the past through the pages of a book. Based on the compelling Melendy foursome, kids were basically just the same as now, with essential differences due to their era. This is a great homage to keeping secrets just for the sake of it, refreshing in our point in history when we're subtly encouraged to bare all on social media. I especially 'get' Oliver's secretive bent, as a fellow youngest child. All four are great at staying mum, but he's the master of keeping things close to his chest.

Yet on the flip side, the Melendys are confident and never hide their lights. The older two in particular, are extending feelers for their futures. You'll find no false modesty from Mona and Rush, who know perfectly well where they excel. Their pleasure in putting themselves out there is satisfying to read.

Tying it all together are seasonal games in the ever-changing backdrop of nature; a menagerie of pets, and impromptu picnics in which sandwiches are thrown together on the spur of the moment. The book is a time machine in itself, making us nostalgic for the 1940s which many of us never lived through. I think my favorite chapter is surely the dramatic night when poor Rush gets stuck up in his treehouse.

Bring on the third book in the series. I'm still extra keen.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

April 23, 2025

Jane Austen's Novels Ranked

This year, 2025, marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. All year long, her fans around the globe will be celebrating with all sorts of tributes, probably culminating around her actual birthday on December 16th. I must add mine all the way from Adelaide, South Australia to the mix. I'll start off with this ranking of her six major novels. (You might also like to check out my rankings of the Bronte Novels, and the Narnia Chronicles.) Now since there is not an Austen novel I don't like, this took a bit of careful thought, but here goes.

1) Pride and Prejudice

Placing this at the very top of my list isn't just because it is one of the pioneer hate-to-love novels. It has never been knocked off its pedestal despite centuries of additions to what has now become a famous trope. That is saying something pretty impressive. It brilliantly delves into motivations for off-the-cuff comments and snap judgments alike. And the superb social commentary and excellent cast of characters makes it a comic masterpiece.

2) Northanger Abbey

Catherine, the gullible teenage bookworm, earns this book its spot as my second favorite. I see such a lot of my old teenage self in her. Assuming that everyone else looks at the world through her own good-natured lens is Catherine's downfall, as she has such a lot to learn about shady social climbers and fickle fortune hunters. In addition to this, it's a powerful homage to the power of books and the unflagging enthusiasm of fangirls (and guys) throughout the centuries. Loyal readers keep any book's momentum alive and well. It has always been that way and always will be.

3) Persuasion

Anne and Wentworth's second-chance romance is a satisfying burn. The chemistry between them is easily ignited after years of hurt feelings, which makes it a wondrous discovery that those bridges have not been burned. I also enjoy seeing Wentworth get more than he bargains for by the rash behavior of Louisa, a young lady who he initially admires for being Anne's antithesis. And Jane Austen gives naval men a plug, probably on behalf of several hard-working brothers of hers. They surely deserved it.

4) Sense and Sensibility

Elinor Dashwood is another favorite heroine of mine. She has a kind heart, yet her bull dust radar is very finely honed. And her love interest, Edward Ferrars, deserves kudoes too, for staying quiet and modest in such a pretentious family unit as his. Along with this, we all have a lot to learn from Marianne's months-long meltdown, and the existence of despicable young men like Willoughby, who'll ghost a girl for such mercenary, self-focused reasons. Girls, it really is him, not you!

5) Emma

There have been quite a few classic stories about the perils of matchmaking, and this is one of the very best. The smug Miss Woodhouse truly needs to learn that she's not as brilliant at it as she thinks she is. Her guinea pigs live deeper lives than she sees on the surface, and her stuff-ups are a hard way to learn this. The men and women she manipulates are not mere pawns on the board, and she is not a master chess player. How could Emma possibly foresee the secret plans of the likes of Mr Elton, or Frank Churchill? Even characters we rarely see on the page come across as complex and 'real.'

6) Mansfield Park

I'm not a great fan of Fanny and Edmund's romance or their neat, critical assessments of other people's characters, but I love the social commentary and family saga. Fanny occupies an Old Testament prophet type of position. She's the only person who clearly sees moral corruption simmering away, yet she's also the least esteemed member of the family. What can be done? This novel has one of my least favorite Austen characters of all time, Mrs Norris, which might help drag it down to sixth place, although her disgusting nature is a clear sign of Jane's brilliant writing.

Well, that's my ranking, and it took a bit of pondering to figure it out. I guess there must be every combination of these six possible, as Austen fans are as numerous as the sand grains on a beach. I tend to think Northanger Abbey doesn't get the love it deserves, which accounts for my high ranking. Overall, this makes me want to read every single one of these six all over again. You can check out my reviews of all of them on my Jane Austen Page.

Now tell me, what would your ranking be?

April 16, 2025

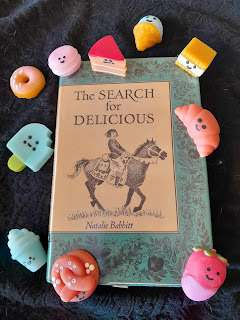

'The Search for Delicious' by Natalie Babbitt

I remember being extremely enchanted by this book during silent reading sessions at Primary School. When I came across a copy at a secondhand book sale, I decided to see if it lives up to my memory of it.

MY THOUGHTS:

The Prime Minister of a nameless kingdom with medieval vibes is writing an official dictionary, yet he's stumped when he reaches the word 'delicious'. Nobody can agree on an example, for in this volume, a definition alone won't suffice without back-up. Arguments erupt in the royal court, and civil war seems imminent.

The king decrees an official poll of every citizen in the kingdom. Surely selecting the most popular choice must be the obvious solution. The PM's adopted son, Gaylen, is assigned the job of riding around on his horse, recording votes. But it's soon clear to him that there are almost as many definitions of delicious as there are people. Finer nuances make the ultimate decision even more elusive, for people love to split hairs. (For example, an apple tart can be flavoured with cinnamon rather than nutmeg, and the addition of sharp, yellow cheese really sets it off.) Although fun at first, all the unrest and bitterness soon rests heavily on this 12-year-old's shoulders.

To thicken the plot even more, the queen's evil brother, Hemlock, takes advantage of all the rioting to attempt to steal the kingdom. His secret knowledge of the magical underworld stands him in good stead. There are ancient woldwellers living up trees, busy dwarves forging treasures in the depths of caves, and the sad legend of Ardis, a beautiful little mermaid who lost her doll.

Young Gaylen is in big trouble. If being pelted with rotten vegetables isn't enough to deal with, he stumbles across the insurrection plot and feels in way over his head.

But Gaylen is the archetypical innocent protagonist who experiences fantastic strokes of luck. Most are overly coincidental by far, and the significance of these chance encounters never strikes him until much later on. The boyish, pure-hearted hero has what the dastardly villain lacks, which is the consistent knack of being in the right place at the right time.

Of course, circumstances cause an entire army to reach a unanimous agreement about the ultimate delicious treat, and it's all Hemlock's fault. (Even as a kid, I remember feeling somewhat let down, and still think that 'delicious' isn't quite the right word. To say more would be to reveal a spoiler.)

It's quite a cool little tale about the potentially disastrous foibles of human nature. The boy, Gaylen, often shakes his head over the silliness of taking such a survey at all, but haven't many wars throughout history been triggered by ridiculous disagreements? Pitshaft, the dwarf, nails it when he says, 'People are so foolish, they waste their time even though they have so little of it. We (dwarves) have forever, yet we never waste a moment.'

My best takeaway as a grown-up reader is the lyrics of this song from Canto the minstel.

'The way is long and high and hot,

Be gay and sing! You may as well

Be feeling light of heart as not.

The way is long and high and hot,

But mime the birds and praise your lot.

Sweet freedom is the tale to tell.

The way is long and high and hot,

Be gay and sing! You may as well.'

🌟🌟🌟½

April 10, 2025

'The Saturdays' by Elizabeth Enright

MY THOUGHTS:

I discovered this treasure in a secondhand bookshop when I needed a bit of cheering up. It's the first novel in a series about the four Melendy siblings, who live in New York City around the late 1930s or early 1940s. Their widowed father is a writer and lecturer, and their warm-hearted housekeeper, Cuffy, holds down home base, pretending to have a short fuse although they know her patience is bottomless. The pragmatic handyman, Willy Sloper, is almost a member of the family too, since neverending maintenance work, especially on the temperamental furnace, keeps him always nearby.

The four kids each receive a weekly allowance which is welcome but limited. One day they come up with a brilliant egalitarian idea. Each week they will pool the total and take turns on Saturdays doing something more grandiose and expensive than they'd ever be able to afford separately.

Aesthetic and whimsical Randy (short for Miranda), kicks off by visiting an art gallery exhibition where she makes a stunning discovery about somebody they thought they all knew well. The following weekend, her mischievous and musical brother, Rush, attends an opera and makes an unexpected friend who ends up being a life saver. Next, their eldest sister Mona, pushes the boundaries with an impulse that shocks her family. Then the youngest, little Oliver, decides to break out as a rebel by making a sudden circus trip.

This is just the sort of vintage juvenile fiction I love. All the good-natured snarky comments never hide the fact that they all have each others' backs. Self-conscious Mona likes perfume to be so strong that people can enter a room 24 hours after you've left and still know you've been. Inquisitive Oliver hasn't learned his limits with food, and gorges until he busts. Resourceful Rush develops wonderfully sensible ideas about accepting charity, and dreamy Randy has a knack of discovering things that belong to her in a special way that has nothing to do with ownership.

The adults are great characters too, with combinations of strengths and flaws. Somehow, it tickles my fancy when down-to-earth old Willy humors young Rush by discussing opera with him. When he finally tells his twelve-year-old friend, 'What you see in stuff like that is more than I can understand,' I had to laugh.

Perhaps Randy speaks for all of them when she comments that although their lives are probably pretty humdrum as a rule, somehow they never seem humdrum. They all have the fortunate skill of appreciating the small things, despite occasional bouts of boredom.

Going on with the rest of this series is a matter of course.

I reckon these kids might've been born roughly the same time as my Dad, which gives me a buzz. Now I must add Rush and Randy to my favourite bro-and-sis bonds in classic lit. They even share the same dream one pivotal night. And if you do pick up the book, I think my favourite chapter is the one with the furnace. You'll instantly know when you get to that spot.

(Note: Its structure and theme reminds me a bit of this book which I read about a year ago, but I think the intentional nature of the Melendy family plan makes The Saturdays the superior novel.)

Look out for more of my reviews of The Melendy Quartet, which are coming soon.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

April 1, 2025

'The Dickens Boy' by Tom Keneally

Summary: The tenth child of Charles Dickens, Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, known as Plorn, had consistently proved unable 'to apply himself ' to school or life. So aged sixteen, he is sent, as his brother Alfred was before him, to Australia.

MY THOUGHTS:

This is an excellent novel strongly based on fact, although I'm not a fan of the dull, minimalistic cover design. It doesn't do the story justice. But the novel itself is a great addition to my 2025 Aussie Book Challenge.

The main character, who tells his own story, is Charles Dickens' youngest son, Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens. When he was a baby, his father nicknamed him Plornishmaroontigoonter, and our teenage protagonist still introduces himself as 'Plorn.' Poor Plorn is sent down to work on an Australian sheep station, ostensibly to help him apply himself, since he wasn't excelling at school in Britain.

25-year-old Alfred Dickens, one of Plorn's elder brothers, has already lived in Australia for some time. Having been sent down by their 'guvnor' for similar reasons, Alfred is redeeming himself by working steadily as the manager of another sheep station. Alfred assures Plorn that if he tries to come across as a 'sportsman and a likeable chap,' the Australians will warm to him.

Plorn enters the colony hoping for some relief from his terrible secret. He's never read a single one of their father's books. His justification is the same as that given by many modern readers. The 'armies of paragraphs' crammed into them are offputting at the outset. Plorn has heard enough snippets over the years to do some believable bluffing, but he's in for a nasty shock. The people down in the colony are as hungry for his father's stories as any Briton could possibly be. For them, Charles Dickens is a cult hero, a megastar, a literary deity to stir up their latent sensibilities. 'Your father is like an extension of the gospels.'

Plorn is bamboozled on two levels. Firstly, he considers himself an awkward and unworthy object of vicarious celebrity. 'I'm just a schoolboy, and not a smart one.' All the attention is cringeworthy and embarrassing. Secondly, he suspects that his father's feet of clay unqualify him for his untouchable reputation. Not least is the fact that the guvnor has sent away Plorn's mother, who bore his ten children, to begin his fling with Ellen Ternan, an actress far younger than himself.

As with many youngest children, Plorn is a peacemaker; an empathetic seventeen-year-old who longs to believe the best of everybody. Hence, he's discouraged by his heart-to-hearts with Alfred, who insists on pointing out that when their father wanted to get rid of someone in his books, he either killed them off or sent them to Australia. Plorn tries his best to ignore Alfred's implication for the pair of them, but it becomes increasingly harder to turn a blind eye. For the lofty Charles Dickens, those who don't measure up to his great expectations (yep, pun intended) are sent to 'that pit at the end of the world where you toss useless folk in,' characters and sons alike.

The wide, hot land is nothing like anyone imagined, and everyone is essentially winging it, while Britain is still referred to as Home with a capital H. For young Plorn Dickens, it becomes a crucible in which he faces up to some home truths about himself and his family that he might have overlooked if he'd stayed in England. He comes across bushrangers and bandits, natives and shearers, a wannabe author, a cougar who wants to 'have her Dickens' and a gracious housekeeper who professes to value Catherine Dickens' cookbook over all Charles' novels. In the process, Plorn becomes a different person than the boy who might have stayed home.

Perhaps a better one.

My overall verdict is this. If you're an Aussie, this is well worth a read. Same if you've plowed through all or most of Dickens' major works. If you can tick both boxes (like me) this is unmissable, because we will get all the references for a start. Not to mention, we get to enjoy these two likeable Dickens sons, who felt themselves to be fall-shorts but who experienced and appreciated the land down under, which their father never once set foot in.

🌟🌟🌟🌟½

March 25, 2025

'There are no Accidents' by Robert H Hopcke

Summary: A woman is set up on a blind date with the same man twice, years apart, on two different coasts. A singer's career changes direction when she walks into the wrong audition. A husband gives his wife an unexpected gift—after she repeatedly dreams about that very same item.

It was Carl Jung who coined the term "synchronicity" for those strange coincidences that we all experience—those moments when events seem to conspire to tell us something, to teach us, to turn our lives around. They are the strange plot developments that make us feel like characters in a grand, mysterious story.

MY THOUGHTS:

The subtitle of this non-fiction book is 'Synchronicity and the Stories of our Lives.' I don't review every non-fiction book I ever read, but make an exception for those with material I'd really love to remember. I discovered this book at a secondhand shop, which itself might be a stroke of fortune.

The word 'synchronicity' itself was coined by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, and the simplest definition is, 'a meaningful coincidence.' In this book, Hopcke first puts forward five hallmarks that are generally ticked off in any typical synchronistic event.

1) They are acausally connected, instead of having any sequence that can be attributed to cause and effect.

2) They often occur with the accompaniment of deep emotional resonance. Often this occurs at the time of the event itself, but not always. (I've experienced a combination of on-the-spot and delayed revelations.)

3) The content is symbolic in its nature. (This opens interesting fields such as the collective unconscious, which is something like a psychic storehouse of the human race that contains collections of symbols or 'archetypes' which may take the form of people or situations. My interest in archetypes has been stirred as a result of reading this book.)

4) They often occur at points of important transitions in our lives.

5) They tend to contain a numinous tone. In other words, when they occur, we feel that we are undeniably and irresistibly in the presence of the divine.

Hopcke advises us early on to willingly listen to whatever life presents. And being a writer, I love his suggestion that given the dramatic quality of synchronistic events, it may be that true life sometimes mimics fiction, rather than vice versa.

I also appreciate the idea, reflected in many of these anecdotes, that when things don't go to plan, the results may prove to be fortuitous rather than disastrous. Jung posited that they 'relativize the ego.' That is, they help tame our human desire to be controllers and masters of everything we face. Instead, synchronicities may lead us to see things from a larger perspective, with a far broader wisdom than anything we can comprehend. (Whew, I'd love to think so.)

Over the years I've come across thoughts by Christian authors on similar topics, but these writers have an agenda, so to speak. It's refreshing that Hopcke considers himself to hold an agnostic point of view, yet has still researched deeply enough to see that something deeper than what we can wrap our heads around is at play.

He believes that nocturnal dreams may be assumed meaningful, but not in the sense that dream dictionaries with alphabetical listings may have us believe, for humans are not formed from cookie cutters and nothing is that pat. Similar dream scenarios may hold different significance for different people.

Hopcke suggests that examining synchronistic events is similar to interpreting the meaning of a story, which every English and Creative Writing student is drilled to do. A vast variety of possible applications abound, and we must take into account our subjective experiences (how they made us feel, what they made us think, how they fit into our overall stories).

I loved reading the many examples he's collected from several people. Some of the synchronicities seem feather-light, yet still tick the features from the list above. Reading these reinforce to me that I've experienced several in my own life. I won't inflate this review by including them here, but if I ever write about them in detail, I'll link it back to this post.

I gotta love the thought that some invisible hand at work supplies our bulwark and meaning all through life, gently shifting scenes into place when we're clueless. That sort of evidence is abundant here.

I'll finish off with this quote in full, from the father of synchronicity, Carl Jung.

'The problem of synchronicity has puzzled me for a long time, ever since the middle twenties when I was investigating the phenomena of the collective unconscious and kept coming across connections which I simply could not explain as chance groupings or "runs". What I found were coincidences which were connected so meaningfully that their chance occurrence would represent a degree of improbability that would have to be expressed by an astronomical figure.'

Wow!

🌟🌟🌟🌟

March 18, 2025

'Three Act Tragedy' by Agatha Christie

Summary: Who wouldn't be pleased to attend a small dinner party being held by Sir Charles Cartwright, once the leading star of the London stage? At his "Crow's Nest" home in Loomouth, Cornwall.

Unfortunately, thirteen guests arrived at the actor's house, most unlucky. One of them was a vicar. It was to be a particularly unlucky evening for the mild-mannered Reverend Stephen Babbington, who choked on his cocktail, went into convulsions and died. But when his martini glass was sent for chemical analysis, there was no trace of poison -- just as Hercule Poirot, also in attendance, had predicted. Even more troubling for the great detective, there was absolutely no motive!

MY THOUGHTS:

Sir Charles Cartwright, the famous retired actor, is having a party when one of his guests, Reverend Stephen Babbington, dies suddenly after sipping a cocktail. A short time later, celebrated nerve specialist, Sir Bartholomew Strange, dies drinking port at a gathering of his own. Alarmingly, some of the guests were present at both functions. And in both instances, the verdict turns out to be poisoning by means of a highly concentrated dose of pure nicotine.

Sir Charles convinces two friends to help him figure it out. Mr Satterthwaite is an elderly patron of the arts. Miss Hermione Lytton Gore (nicknamed Egg!) is a star-struck girl who's fallen heavily for Sir Charles. Together, this unlikely trio takes on an extremely puzzling mystery.

Who would want either of the two lovely gentlemen dead; community pillars as they both were? How could they possibly be connected, if at all? Luckily a fourth truth-seeker pops up, who was present at the first murder, and whose interest has been piqued. It's our old friend Hercule Poirot. The professional detective understands that the amateur trio think they're onto it, so he graciously offers to stand back and not be a party pooper. Poirot will let Sir Charles have the glory of unraveling the crimes even if he has to spoon feed very broad clues.

Okay, first for the nitpicking. To start with, there's something a bit tasteless about making any sort of a game out of murder, don't you think? Secondly, Sir Charles is way, way too old for Egg, even in an era when young girls idolized older men. And thirdly, getting used to her strange nickname takes a bit of effort at the outset. (I noticed a couple of other reviewers claim that was too big a stumbling block for them altogether, but I wouldn't go that far. A young woman has a right to call herself Egg if she wants to.)

Now the minor grumbles are out of the way, the solution is so audacious and ingenious. There was no way I could have possibly figured this one out, although several clues were laid before us. The red herrings are fantastic and the cast of suspects is varied, interesting, and seemingly motiveless across the board. There is a nice little lover's triangle, low-key as it is. And Poirot shines at his very best, and even offers a valid reason to Mr Satterthwaite for his continual boasting. He claims that making himself a deliberate target of people's gentle ridicule helps put them off guard regarding him. Hmmm.

Other than all that, I wonder if Egg's defense of the Christian faith mirrors Christie's own.

'I really believe in Christianity, not like Mother does - with little books and early service and things - but intelligently and as a matter of history. The Church is all clotted up with the Pauline tradition, in fact the Church is a mess, but Christianity itself is alright... The Babbingtons really were Christians; they didn't poke and pry and condemn, and they were never unkind about people or things.'

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

March 11, 2025

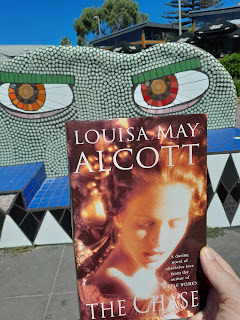

'A Long, Fatal Love Chase' by Louisa May Alcott

Summary: 'I'd gladly sell my soul to Satan for a year of freedom,' cries Rosamond Vivian to her callous grandfather. A brooding stranger seduces her from the remote island onto his yacht. Trapped in a web of intrigue, cruelty, and deceit, she flees to Italy, France, Germany, from Paris garret to mental asylum, from convent to chateau - stalked by obsessed Phillip Tempest.

Two years before Little Women, serialized in a magazine under the alias A.M. Barnard in 1866, this was buried among the author's papers over a century.

MY THOUGHTS:

Whew, Louisa May Alcott does Wilkie Collins here. This is the Gothic thriller she wrote a couple of years before Little Women. My edition's title is abbreviated to, 'The Chase' but I prefer to use its full dramatic, somewhat spoilerish name. It was rescued from the woodwork and published posthumously as recently as 1995!

Rosamond Vivian is stuck in a home near the sea with her gruff grandfather, and longs to stretch her wings. In the very first paragraph she declares that she'd gladly sell her soul to Satan for a year of freedom. Enter Phillip Tempest, a 'pupil' of her grandfather's. He sports a scarred forehead and looks exactly like a picture of Mephistopheles, the folklore demon. A tree that was planted the day of Rosamond's birth is struck down by lightning the night she meets him, but she overlooks this chilling omen and falls prey to his charm.

They get married and she cruises around the Mediterranean in his yacht, the Circe, having the time of her life. Then Rosamond discovers what a bad egg he is; a liar with a seamy past who's completely devoid of conscience. Rosamond decides to flee, but Phillip is always on her trail. Even though the world is a huge place in which to vanish, especially given rudimentary 19th century technology, Tempest and his creepy henchman, Baptiste, keep tracking her down.

The scenes of the novel, scattered across Europe, include a convent and a lunatic asylum. When Rosamond gets to know the heroic and sexy young Father Ignatius, who made his vows a bit too prematurely, she realizes that her love for Tempest was based on naivety and restlessness. Yet her girlhood mistake is there to haunt her. She can't throw off the stalker from hell, who presumably never heard the saying, 'If you love somebody, set them free.'

If you think it sounds melodramatic and theatrical, you'd be right.

In terms of the Little Women universe, this reminds me of a plot Jo might have written for Meg to act the leading role in. And to judge from Jo's experiences writing sensationalized potboilers in the big city, Alcott herself became a bit shamefaced about her earlier writing. Although Louisa initially enjoyed writing it and resisted her publisher's request to come up with a wholesome 'book for girls', it appears from the earnestness of her subsequent work that she later changed her mind. I suspect this is the style of work Professor Bhaer surmised that Jo was ashamed to own up to. It is of material such as this that he states, 'I'd rather give my boys gunpowder to play with than this bad trash.' (Haha)

'She was living in bad society, imaginary though it was... she was feeding heart and fancy on dangerous and unsubstantial food.'

That's Alcott's nineteenth century way of commenting that stories like this may well be the junk food of literature. There's nothing overly shocking or gratuitous about The Chase, but nothing inspiring or stirring either. I understand how Alcott might been embarrassed about the quality of her earlier work in retrospect. Now I wonder if it's fair or ethical that this should have been brought to light for publication so long after her death, for I'm willing to bet she wouldn't have wanted it to be.

The dastardly Phillip Tempest states, 'I like horrible books if they have power.' Fair enough, but I'm not convinced this fits that bill either.

'Overcome by conflicting emotions of gratitude and grief, surprise and shame, Rosamond covered her face and threw herself at the feet of the actress.'

In a world in which authors are encouraged to tread lightly, 'show not tell', and rarely name emotions, this is shockingly heavy-handed writing.

Yet it's very interesting for Alcott fans to trace her personal development. Although the distinct genres make it a bit like comparing apples to oranges, the Little Women universe is far more to my taste.

🌟🌟

March 4, 2025

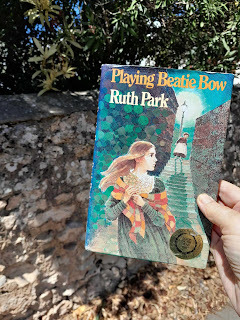

'Playing Beatie Bow' by Ruth Park

I first studied this book as an assigned text for Year 9 English, which is longer ago than I care to admit. It was only four years after it was first published though, so that's a broad clue. Anyway, it was high time to revisit it, for my 2025 Aussie Reading Challenge.

Despite being on my school syllabus, the book lingers fondly in my memory, and no wonder. The story combines two excellent genres, time travel and family drama. What is not to love?

MY THOUGHTS:

It's a true blue Aussie, Sydney setting, and the winner and runner-up of multiple awards, the most noteworthy being the Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year award in 1981 when it was still brand new.

14-year-old Abigail Kirk is fuming mad. Returning home after a major dispute with her mother, she makes a wrong turn, not in space but in time. When Abigail decides to follow a strange little girl with shorn hair who's been hanging around her apartment building, she's led to a bewildering world where the basic street layout is familiar, but strangely old-fashioned and off-kilter. It's the colony of New South Wales back in 1873, where Abigail is still just a few blocks from home, yet over 100 years away.

Owing to an accident out the front, the little girl's family takes Abigail in. That spiky, smart child turns out to be Beatie Bow herself. Beatie's father, Samuel, is a confectioner by trade and former soldier who suffers sudden violent outbursts caused by PTSD. Wise old Granny, whose gift of second sight once burned strong, holds her son-in-law's family together. Gentle cousin Dovey is dutiful and beautiful in a porcelain doll sort of way. Then there are Beatie's two brothers. Sickly, morbid little Gibbie just escaped dying of fever, and can't stop dwelling on it; and Judah, the dependable, sunny-hearted sailor boy steals Abigail's heart.

Ruth Park's sensory detail is immersive, making us feel like eye-witnesses. (For example, Abigail feels grossed out for being more grotty than normal in the Victorian era, although Granny and Dovey are slightly offended, because they take pains to be as clean as they possibly can.)

Abigail overhears mysterious whispers that she's 'the Stranger' who is destined to appear from out of nowhere to save 'the Gift' for the family. And it turns out she accidently carries something on her person that facilitates her leap back in time. So this story is more than just time tourism, there is a vital mystery quest to solve and fulfil before she can hope to return to the twentieth century (or try to return!).

Although I loved it as much as before, I'm taking off half a star because of something I overlooked back then. Poor Abigail gets gaslighted for kicking up a stink regarding her parents, yet I find her reaction to their news is perfectly legitimate. She received a shattering blow to her trust and personhood four years earlier when her father ran off with another woman, and now her reuniting parents expect her to swallow their sudden line, 'We'll all fly off to Norway and be a happy family again.' I don't blame Abigail for questioning and resisting this cheesy new development when it is simply sprung on her. Yet she is treated like a nuisance and a spanner in the works by her mother and her conscience alike.

Consequently, Abigail's experiences in the nineteenth century cause her to whitewash her dad's betrayal merely because he was struck by Cupid's arrow! She herself falls for Judah, who has a momentary leaning her way that lasts no longer than an afternoon, so now Abigail is willing to wipe the slate clean because her father's desertion of his family was all about lurve!! The theme, 'You have to experience love to know how powerful it is,' makes me facepalm in this instance, even though I'm a total romantic at heart. And then Abigail apologises to him!

'What a little dope I was, Daddy!'

Nope, he was the bigger dope. Forgiving him is fair enough, but bearing any reproach and shame on her own shoulders, for totally understandable and natural feelings, irks me. Abigail is gaslighting herself in effect, and Mr Kirk sure gets off lightly.

But overall, I got a lovely book hangover, just as I did before, to the extent that I'm going to discuss some plot spoilers below the red line, in case you're interested.

THE RED LINE - If you want no plot spoilers, read no further.

* I was mildly horrified that during the blazing house fire, everyone forgot Gibbie for so long! Sure, Dovey's bridal chest contained a vital garment, but would that really be the first thing to spring to the minds of Granny and Dovey, as well as Abigail? Actually, I'm more than mildly horrified!

* Nooooo, not Judah!!! I guess he had to perish in that shipwreck (sniff) to validify Abby's last-minute rescue of Gibbie, and preserve the Gift. But it seems a cruel twist for Granny and Dovey to die of typhoid a couple of years later. We also get a glimpse of Mr Bow expiring in a lunatic asylum. Sure, the nineteenth century was brutal, but I wish Ruth Park hadn't added those extra bits.

* The family prophecy seems somewhat problematic. Everyone is sure that out of the four remaining members of the younger generation (Judah, Dovey, Beatie, and Gibbie) it has to be one for death and one for barrenness. But hold on, Samuel and Amelia Bow lost a few other kids in infancy. Why couldn't the prophecy have referred to any one of them?

* Whatever becomes of Beatie and Gibbie in the short term? By the time these two kids have lost everyone (Judah, Granny, Dovey, and their father), they are still only 15 and 14 years old at the most. So young to be totally bereft in a harsh era. Well, at least we know that Beatie eventually becomes a highly successful (and grumpy) classical scholar and headmistress, and Gibbie hooks up with some girl who he presumably marries and has at least one kid with. But oh, like Abigail, the interim stimulates my curiosity.

* The classic time travel hiccup of a future traveler seriously changing the trajectory isn't emphasized in this story, yet Abigail still indirectly saves the life of Robert, the man we assume she eventually marries, and also her friend, Justine, and the two kids. If Abby hadn't plucked their grandfather (however many greats) from the jaws of death when he was 10, they would never have been born.

🌟🌟🌟🌟½

The Vince Review

I invite you to treat this blog like a book-finder. People often ask the question, "What should I read next?" I've done it myself. I try to read widely, so hopefully you will find something that will strike a chord with you. The impressions that good books make deserve to be shared.

I read contemporary, historical and fantasy genres. You'll find plenty of Christian books, but also some good ones from the wider market. I also read a bit of non-fiction to fill that gap between fiction, when I don't want to get straight on with a new story as the characters of the last are still playing so vividly in my head. ...more

- Paula Vince's profile

- 108 followers