Kevan Manwaring's Blog: The Bardic Academic, page 40

January 11, 2015

Better to Light a Candle than Curse the Darkness

First of all, beyond any intellectual ball-kicking, my heartfelt sympathies go to the families and friends of this week’s outrage in Paris where 11 people were shot dead for publishing cartoons, or in the case of the caretaker and visitors, being in the wrong place at the wrong time. As the chaos spread, the fatalities rose to 17, with many others wounded and traumatised. Indeed the whole nation is in shock and mourning, and the ripples of this latest terrorist atrocity is being felt around the world. Today’s mass rally in Paris is the culmination of a tumultuous week which has left France reeling, yet defiant, and a corresponding outpouring of sympathy and camaraderie from across the globe, with even the President of the US stating: ‘Vive La France!’

Charlie Hebdo is a long-running satirical magazine with a tendency towards the more extreme spectrum of topical caricature ��� Private Eye meets Viz perhaps. Certainly more Gerald Scarfe than the witty captions of Private Eye. The editor, Stephane Charbonnier, (aka ‘Charb’) and many of the magazine’s top cartoonists were ruthlessly targeted and gunned down for publishing images deemed offensive to some who call themselves followers of Islam (though many Muslims have spoken out against the attacks, and indeed two of the victims were Muslims ��� a police officer and a staff member). Further casualties and fatalities resulted from the tense fallout leading to a double hostage situation ��� a crisis which the French police force dealt with impressively. Who would have wanted to have been a French gendarme this week? The two brothers who executed the Hebdo attack did so with military precision and ruthlessness. In the name of Al Quaeda Yemen they did their best to start a war ��� let’s hope they do not succeed.

Yes, the attack on Hebdo was an attack on free speech. France is a Western democracy, not an Islamic State ��� people are still allowed to speak their mind. We might not agree with what they say but we defend their right to say it. In a civilized society if someone causes offence then those offended can engage in a debate at best, at worst, file a law-suit. Only barbarians resort to violence. Let it be said: Violence is the recourse of the stupid. It is never a solution. This goes for all parties concerned. Violence begets violence, and he who lives by the sword die by the sword. There is always another way, and those with intelligence will find it. Those who are using the attacks to fuel hateful Islamophobia are just as bad as the thugs with guns.

Yet the attack was against writers and artists ��� and as a writer and artist myself I feel an affinity with the Hebdo staff in that regard at least. I hold my creative freedom as a writer sacrosanct. I encourage my creative writing students to feel the same. When we start self-policing then the Fuckers have won. I am against censorship, but at the same time I believe with creative freedom comes a degree of responsibility. We should mindful about what we cast out into the world with our efforts. As a Muslim cartoonist interviewed on Al-Jazeera said this week (a breath of fresh air amidst the xenophobic soundbites), it is easy to create a crude cartoon that causes offence, it is harder to create one that makes people think ��� that balances the message with an awareness of the impact it might cause. As a Muslim, he finds a middle-ground ��� negotiating a tricky position with skill ��� so why can’t the rest of us? We live in a complicated, joined up world. Nothing is in isolation. We have to be aware of the consequences of our actions, of our art. Take some moral responsibility.

However, I do not wish to defend the reprehensible actions of terrorists, or any driven to violence in the name of whatever justification they choose for their thuggery. So, here are a few final points I wish to make:

Nothing is beyond criticism.

Any organisation or insitution lacking a sense of humour (about itself) is extremely dubious.

A sense of humour is essential equipment for living on planet Earth.

Planet Earth is big enough for everyone’s paradigms but not everyone’s prejudice. Learn to get along. Negotiate the complexity.

There are those instantly ready to be offended, and to resort to violence. Both are mindless kneejerk positions. Get civilized.

Creative freedom is sacrosanct.

With creative freedom comes responsibility.

Violence is the recourse of barbarians. Use your brain. Prove you’re a human being with intelligence.

Bombs are boring.

Guns are for guys with small dicks, or women who secretly crave one.

Happiness is a warm pen.

What I found heartening about Saturday’s march of sympathy in Paris were the placards which read not simply ‘Je Suis Charlie’, but ‘Je Suis Contre Le Racisme': I am against Racism. This I think is a more mindful message. Yes, our sympathies are with the family and friends of those killed; but that does not automatically mean we hate all Muslims, only the hateful few who resort to such desperate extremism. They, and those that support them, deserve nothing but our contempt. I hope one day they choose to rejoin the human race; and that we can learn to work out this whole mess together in a civilised manner.

The human spirit is dauntless, and the human imagination limitless, so I believe it is possible:

A blank page is an invitation to change the world.

January 7, 2015

The Art of Bragging

In the age of mass-vanity projects like Facebook, the art of bragging has never been more rife. Social media risks making of us all self-obsessed narcissists, locked into an endless game of brinkmanship. Looking enviously at our friends’ latest updates, we are forever keeping up with the Jones. The consequence of leading such goldfish bowl lives is continual status anxiety. And yet, once bragging was a bardic art – and perhaps something can be salvaged from it for practical use, as we continue…

The Writer’s Quest

Part 3:

Ego the Giant and the Art of Bragging

The arriving band of warriors are challenged on the shore by Hrothgar’s thane. They bandy words in ritual exchange. The coast-guard accepts Beowulf at his word, and agrees to escort them to Heorot. He arranges for their ship to be guarded. Off to Hrothgar’s hall they set, the sight of which impresses the Geats. Here, they are challenged a second time, by the royal herald. When the King is convinced of their honourable intent they are allowed in. Hrothgar fondly remembers how in his youth he had taken service with King Hrethel of Geatland. He has heard of Beowulf, who now declares his intent ��� to banish the curse of Grendel from the hall once and for all, without arms or armour to boot. Beowulf boasts of his prowess, but at the welcoming feast is challenged a third time ��� by Unferth, the King’s advisor, who mocks the validity of his account of a swimming match against Breca. Beowulf soundly rebuffs this attack on his honour. He wins mead from the hand of Wealtheow the Queen. As the banquet ends and the company departs, Beowulf prepares for the intruder.

Reputation is everything in this Age of Heroes. As our hero Beowulf makes landfall on Danish shores he is confronted by no less than three threshold guardians: the watchman on the wall (who first challenges him on landing); Hrothgar���s herald (who makes him follow the etiquette of the court); and Unferth (who mocks him at the feast). At each of these junctures Beowulf steps up to the mark, as we must ��� no matter how fierce the guardians we encounter.

Remember, they are there to test our tenacity. That is their very purpose.

Although these ���threshold guardians��� could manifest in a myriad of ways (they are the ���Ten Thousand Things��� the Buddhists talk of ��� Maya ��� which we can be easily enamoured/distracted by). In the context of Beowulf if we wanted to get symbolic about things, we could say these three guardians are the Inner Critic, the Outer Critic, and the Envious Friend ��� each of these can sabotage us.

The most insidious is perhaps the first ��� the Inner Critic ��� the voice inside our head that tells us that

we���re not good enough, that it���s not worth it, that it���s all been done before. Some of these messages may actually be hand-me-downs from family, from school: a schoolteacher who ripped up your English essay in front of the class; the sneering sibling; the discouraging parent. We need to exorcise them. Prove them wrong. As with any of these guardian figures ��� see their challenge as a gauntlet thrown down before you. Pick it up, face them, defeat them.

The Outer Critic can be harder ��� it seems apparently objective. The bad review; the poor grade; the heckler; the low turnout; the lack of sales. Many artists make a point of not reading their reviews. Some feel, whatever their sales, gongs (or lack of them) they will do it anyway: create, because they must. Why should anyone deny you of your raison d’etre? The Outer Critics are like the mountain ranges, deserts, or wide oceans the hero must cross to achieve their goal. The tempests of fate, misfortune and the marketplace. Lash yourself to the mast, stop your ears with wax to ignore those maddening voices, and weather the storm. Do whatever you have to, and don���t let the bastards grind you down. Your dream is more important than their hot air. It is oh-so easy to criticise, so much harder to create. The cynic never achieved anything. Let them polish the chip on their shoulder while you get on with forging art (that being said, it has to be acknowledged that there is a place for criticism at later stages of the creative process ��� indeed it is essential; and an insightful review can provide a good introduction, and sometimes enhance one���s appreciation of the end product, placing it within a wider cultural context).

The final one, the Envious Friend, is the so-called buddy piqued by your tenacity, your achievement ��� the very fact you made it happen, or intend to ��� who sabotages you with a passing comment, a snide remark (their own shadow speaking). CS Lewis said to JRR Tolkien, upon hearing him read out an extract from The Lord of the Rings ���not another fucking elf!��� There are those who, through their own insecurity, might want to shoot us down ��� although sometimes their ham-fisted asides might be healthy ballast, to stop us getting too inflated, we shouldn���t let them stop our creative flow. Rather than think ��� ���that person���s success overshadows my own���; instead try ���when a friend follows their star, it empowers me to do the same���. I like Julia Cameron���s dictum: ���Success occurs in clusters and is born in generosity.���165

And yet, we need to be mindful of Ego the Giant. He can easily get out of hand. The way Beowulf is ���bigged up���, first by the poet, then by the watchman, the herald, and then himself, it is no wonder it all seems to go to his head. He is depicted as some kind of super-hero, ���with the strength of thirty in the grip of each hand.��� The sections dealing with Beowulf���s arrival in Denmark, at Heorot, are full of boasting. There is a cultural reason for this ��� the art of bragging (from the Norse god of poetry, Bragi) was an intrinsic part of the warrior culture of the times. A man was as good as his word. The verbal contract was sacrosanct. To go back on your word was to lose honour. And honour was everything. Also, ���beautiful speech��� (that is, ornate speechifying) was as much a part of a man���s ornament as his torcs, armour and sword. Verbal bling to establish status. Finally, in battle, the hurling of insults and swaggering boastfulness was part of the ritual combat that acted as a kind of foreplay to the real thing ��� like fighting cocks brindling their feathers, raising their heads, puffing out their chests and making a lot of to-do before going in. This bardic posturing is simply the preening of wattles. In the poem, this takes on a formal quality when Beowulf states his intention to the hall, like a personal mission statement:

���I shall either perform deeds fitting an earl

Or meet in this mead-hall the coming of death!166

Beowulf���s boast has the gravitas and finality of a vow about it. The clock of destiny has been set ticking, as the poet lugubriously reminds us: ���Fate goes ever as fate must.���167

A writer can choose to do something similar ��� writing down their intention, and committing to it. Mature artists practise the art of containment, carefully incubating their project until it is ready to hatch. What one should avoid doing at all costs is telling an acquaintance (or passing stranger in a bar) about it. Whenever someone says: ���I am going to write a novel���, the chances are they won���t even start it, let alone finish it. If they were serious, they would be doing it, not talking about it. And two other things: you can tempt fate by doing so (if you want to make the gods laugh, tell them your plans); and you risk talking the life out of a project. Some ���writers��� love talking about the book they are going to write and sharing the intricacies of the plot, the wonderfully quirky characters, the thrilling scenes ��� and you can hear the steam escaping from the boiler. It is all hot air and bluster ��� and their engine is left depleted. They are getting off on the idea of doing it, rather than the act of doing it. It can be buzz, when you feel fired up ��� but channel that into the actual writing. Write while the fire is in the head, and keep writing ��� you might find you manage to write half the first draft in one sitting, or even the whole thing (as Kerouac famously did with On the Road in a six-day amphetamine haze). This is when the ego can be your ally ��� it can give you the strength, the self-belief to keep going. You need to believe in yourself ��� if you don���t, who will?

The ego is a vehicle you can use to deliver your message; as long as it doesn���t get out of hand. Don���t let your ego become a boy-racer. Let it be the ���Parker��� to your ���Penelope���, and your FAB1 will cruise to its destination, not end up a burnt-out shell in a ditch.

Beowulf is challenged in the mead-hall by the malcontent Unferth ��� about a particularly swimming-match undertaken against a childhood friend, Breca, who apparently won. For Unferth:

���His bold sea-voyaging, irked him sore;

He bore it ill that any man other

In all the earth should ever achieve

More fame under heaven than he himself.168

Rather than being derailed by this (which would have disastrous consequences for Heorot) the hero rises to the challenge ��� dispatching Unferth���s ungracious attacks on his reputation like so many monsters of the deep (���To slay with the sword-edge nine of the nicors��� 169). Beowulf���s riposte casts himself in an even better light ��� he was delayed in completing the swimming-match because he was attacked by sea-monsters (���The grisly sea-beasts again and again/Beset me sore.��� 170). He wrestled with them to the sea-bed and slaughtered them all, making the shipping lanes safe for all. Swimming for five days in a freezing sea, wielding a sword and wearing chain-mail, fighting sea monsters single-handedly … it all sounds rather far-fetched, and yet we are expected to swallow it. The inhabitants of Heorot clearly do, responding to the bragging match in good spirits ��� this is the equivalent of an Anglo-Saxon rap battle. Beowulf���s boasts become outlandish:

���Bloody from battle; five foes I bound

Of the giant kindred, and crushed their clan.

Hard-driven in danger and darkness of night

I slew the nicors that swam the sea������ 171

It would appear that a warrior���s boastfulness is linked to his power ��� that strong words give a keener edge to his sword (akin to shamanic power; a medicine man singing his wares; a doctor in a mummers play stating his proficiency; a New Orleans Mardi Gras ���Indian��� chief strutting his stuff):

���In the shades of darkness we���ll spurn the sword.��� 172

What might appear to us as simply swagger and braggadocio is a way of preparing for the task ahead. Talking ourselves up (e.g. imagining ourselves as the writer we can be) might be a way of helping to make it happen ��� we enlarge our sense of self, and then step into that space. The opposite ��� being self-deprecating ��� can be self-defeating. Talking ourselves down can just be a cowardly ���get out clause���, a petulant cop out (like saying: ���I didn���t want to do it anyway���). Cynicism can be a mask for fear of our own failure. If we put everything ���down��� (including ourselves) then nothing will be a disappointment. We don���t have to try. We have let ourselves off the hook.

Attempting the ���impossible��� ��� creating a work of originality and stunning skill ��� takes courage and a certain barnstorming attitude. The odds are stacked against you. But everyone loves an underdog. We love to root for Samson. It looks like Goliath is going to give him a pounding. Prove them wrong!

Beowulf sees off his competition ��� wiping the floor with Unferth, the epitome of sour grapes. What the Geatish champion says is almost irrelevant ��� it is the way he says it, with such conviction. Nothing can shake him; a quality that the King appreciates. Hrothgar values: ���the warrior���s steadfastness and his word���, and allows him to join the feast to ���relish the triumph of heroes to your heart���s content.��� He has earned a taste of the hero���s portion ��� by stepping up to the mark (unlike the niggardly Unferth).

By not hiding his light under a bushel he wins the favour of the Lady of the Hall, Hrothgar���s comely wife ��� who, in the role of mead-giver, is a variant of the Goddess of Sovereignty figure:

���Then the woman was pleased with the words he uttered,

The Geat-lord���s boast; the gold-decked queen

went in state to sit by her lord.���173

In her sun-like imagery she is worth more than gold itself ��� for Beowulf has won the Muse. By being in his power, (potently fulfilling his potential) he has attracted her. The awen has descended and the Goddess graces him with Her presence. For a deeper exploration of ���Courting the Muses��� see The Dragon���s Hoard. But, for now, let us end this testosterone-driven section with a footnote to the god of bragging.

We get the word and notion of ���bragging��� from the Norse god of poet, Bragi, who drunk of the skaldic mead stolen by Odin from a giant���s daughter ��� thus, the ���gift of the gab��� is seen as a gift of the Gods. An important caveat ��� as Odin flew back to Valhalla, godly stomach bloated with the mead he had guzzled down, some of it ���leaked��� out and fell to Earth��� Those who received this divine micturation (Odin���s urine), instead of the good stuff direct from the source, have a tainted gift (politicians come to mind…). Their lips are lubricated by the bladder, not the vat (perhaps that is why the fool���s symbol is the ���bladder-stick��� ��� to flag up their seemingly foolish talk and acknowledge their mandate for ���taking the piss���). Yet Bragi���s gift is a double-edged sword. Bragging can easily become ���full of sound and fury, signifying nothing��� ��� as in the classic pub bore; a drunken tongue-lashing; a talk-show host; or Prime Minister���s question time: rival primates either side of a territory-bounding stream, banging their chests and raising a din. We need to follow Beowulf���s example ��� he decides to face his foe in single-combat, unarmed. When all the noisy revellers have gone to bed, he will be left to face his enemy alone. Stripped of the showy trappings of his personality ��� his ego ��� he is ready to confront the painful truth.

Ego the Giant and the Art of Bragging questings:

List your best qualities.

List your worst.

Consider both lists. What would help you in your Writer���s Quest? What would hinder?

What messages does your Inner Critic give you?

What messages does your Outer Critic give you?

What messages does your Envious Friend give you?

What messages would you like to give to them? Write them out, read them out, shout them out!

Create a caricature of yourself, exaggerating your qualities. If you can draw, do this on a balloon. Then pop it. Or make a pi��ata of yourself and take a baseball bat to it. Learn to laugh at yourself at regular intervals. You are fallible and sometimes foolish. That���s okay.

Create a scrapbook or album of your achievements. Reflect on what you can do, have done, and will do. Write a series of affirmations reminding yourself of these.

Find a ���believing mirror��� ��� someone who wants to support you in your creative journey. Book your tired old ego in for a massage now and then.

December 24, 2014

Smooring the Hearth

Solstice Sunset

Resisting night’s gravity

I rise to the Heavens,

clay on boots,

dusk at my heels,

slipping up to the

lonely grove on the brow,

where a year ago,

we planted a circle of hope.

Now I stand alone

in silent vigil.

Aurora of the day

sliding away, behind

Rodborough’s bear shoulders.

It is a satisfying death –

a great actor’s swansong.

A star born for this moment.

The lights fade, and, on cue,

another nova.

No desecrating ruckus

at a stone circle is needed

to mark this annual valediction – leave

the vandals to their

trilithon abuse and stoned selfies.

I have no need of the Am-dram

of dodgy rituals,

the posturing of ill-cast hierophants.

My gaze is for the sun alone.

Quietly, I say goodbye.

Burning News

The old year

is an empty grate,

solstice-black and cold

as a spurned lover’s heart.

Waiting to be filled with

kindling – scrunched news,

or the celebrity tittle-tattle

that passes for it

these days,

fat splinters of shattered tree,

glottal stops of coal,

black bile of angry mines,

the simmering earth

beneath our feet. Its fury

on slow-burn. The fuse of

ancient forests sizzle.

Coal scuttle, clatter and clinker.

With the rasp of a match,

paper curls, catching flame –

spreading like hungry gossip.

Inflammatory rumours

blaze into headlines of fire,

snagging our gaze.

We try to turn away,

but too late.

We’re hypnotized.

Smooring the Hearth

The clock ticks towards

the midnight chimes.

The sands of the year drain away.

Sip your anaesthetic,

reflect upon all that has gone,

the deeds un/done, the words un/said.

Bank the fire down, my friend,

before going to bed.

The memories glow and fade

like the coal, slow time

locked in its fossil heart.

Each a dream, once cherished,

come morn, a pail of dust

to be scattered on the dormant earth.

The day a squall of rain,

the nights come as fast.

The solsticed sun instructs us

to hiatus, to put down our tools.

Endless struggle, surrender arms,

as the Christmas ceasefire commences.

For a while we no longer

have to be anything.

Merely drop down into our being.

It is okay, friend, we can stop buying.

We can stop pretending to be nice,

so desperate to be loved back,

to be popular. For surely,

this is the measure of success.

That, and how much you own.

What you can show off to visitors,

the guests guessing your soul

from what’s on your shelves.

Shallow the depths of society’s

criteria. As though our lives

are no more than a lifestyle magazine,

a trending meme.

The fire dies down,

and what is discarded

slips through the bars of the grate.

Leaving the sine qua non of embers –

the truth only found

at the eleventh hour,

say, on the eve of execution,

when we face the cold, naked fact

of our mortality, our swift sparrow-flight

the length of a mead-hall.

Yet still, we bank the fire down –

thanking the warmth and light it has

bestowed, its borrowed grace –

in the hope that come dawn,

the last star can rekindle

our wintering king,

before it winks out

vanishing with the night.

Poems copyright Kevan Manwaring 2014

December 18, 2014

Summoning the Hero

The Writer’s Quest, part 2

Enter the Hero – Beowulf steps up to the role

Enter the Hero – Beowulf steps up to the roleAt this time, Beowulf, nephew of the Geatish king Hygelac, is the greatest hero in the world. He lives in Geatland, a realm not far from Denmark, in what is now southern Sweden. When Beowulf hears tales of the destruction wrought by Grendel, he decides to travel to the land of the Danes and help Hrothgar defeat the demon. He voyages across the sea with fourteen of his bravest warriors until he reaches Hrothgar’s kingdom.

Every creative act is an act of courage – it is ‘yah-boo-sucks!’ to death, to oblivion, to mediocrity, to being a passive consumer of life. We have everything against us – common sense; the pressure of earning a living; unhelpful peers; inner critics; crazymakers; noisy neighbours; that household chore that really needs your attention; that cold call; Climate Chaos; global financial meltdown; random asteroids and super volcanoes threatening to Destroy The World in an instant! See these as threshold guardians – they are the equivalent of the three-headed dog Cerberus that guarded the entrance to the realm of Hades. They are there to test your mettle, your tenacity. How much do you want to follow your dreams? Is your Push bigger than your Pull? Hollywood screenwriters use the useful idea of the ‘Fear/Desire Axis’ – which, despite its name is not some terrorist cell, or Bond-like super-baddy organisation. Basically, the actions of every character (and, possibly, every human being) is governed by the principle. Imagine it like a see-saw, with Fear at one end, Desire at the other. When a character’s desire outweighs their fear, they move forward. When that mean old bully fear tips the balance, they freeze or retreat. The locus of optimum dramatic tension is the tipping point between the two – the trick is to sustain this as long as possible. Shakespeare kept Hamlet stewing in his own juices for five acts, prevaricating, unable to act. This was the Prince of Denmark’s fatal flaw – he oscillated between ‘to be or not to be’, like some dodgy alternator. If he had killed Claudius in Act One, Scene One – end of story. Instead, Shakespeare wisely spun it out and elicited powerful drama from the psychological anguish experienced by the Dane at his tipping point, creating early Nordic noir.

`Yet, finally, the Hero must act – whatever the consequences. In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo and Sam reach the uninviting entrance to Shelob’s Lair, reeking of carrion, plot snags and foul things. Neither of them are keen to enter – but they have a mission, to take the One Ring to Mount Doom and destroy it. This ‘desire’ outweighs their ‘fear’ and, steeling themselves (Frodo, with Sting) they step into the dark. This makes them heroes. Of course, if they had thought – ‘sod this for a game of soldiers’, and gone back to the Shire, they wouldn’t have been (and they wouldn’t have found much of a Shire to go back to). Novelist John Cowper Powys talked about how a character’s behaviour is governed by a ‘concatenation of imperatives’161 – incrementally, things build up (like ounce weights on the scales) until the protagonists simply have no choice (or so it would seem to them), or if they do, it’s a Hobson’s Choice – a choice which is really no choice at all.

And so into the darkness the plucky hobbits step – with their magic sword in one hand, and the Light of Elendil in the other. And so must we, as writers – armed with only a pen (or keyboard) and the frail light of our inspiration. In the Welsh legend of the bard Taliesin, Gwion Bach is reborn shining with awen (inspiration), stolen from Ceridwen’s cauldron – ‘Behold the radiant brow!’ cries the weir-ward when he is rediscovered, a helpless babe in a coracle. Consumed by our ‘illumination’ we venture into the Perilous Realm, like Wandering Aengus in WB Yeats’ classic poem: ‘I went for a walk in a hazel wood because a fire was in my head…’

Setting off on the Writer’s Quest of the creative process is perhaps akin to being a knight in a medieval romance, venturing into the forest (although we are probably more like Parsifal at this stage – the Holy Fool – more than the accomplished Paladin). Be prepared to make a fool of yourself, turning up at Court on a donkey in a patchwork costume. Let yourself make mistakes – give yourself permission – because so much success comes from creative ‘failure’, from trial and error and happy accidents. Embark in the spirit of creative play – and you will be more likely to create something original. Start thinking that you ‘know it all’, that you have the answers, and you will have nothing to learn (and readers will probably be less inclined to listen). Start your quest with questions – and your journey will be a journey of discovery, fuelled by curiosity and delight, some of the essentials for a writer.

10 Essentials for a Writer

Pen. Paper. A lack of excuses.

Curiosity & Delight.

A willingness to say ‘yes’ to life/a rebuttal of the ‘no’s’.

Ability to rewrite and listen to feedback.

Staying power (an internal composition engine).

An appetite for adventure.

Risk-taking.

Boldness.

Humour.

A healthy book habit.

Gawain had a pentagram on his shield to remind him of the ‘five Christian virtues’. In Scotland, at the Castle of the Muses, I met a South-African ‘knight’ called David told me of the essential chivalrous qualities as he sees them. A knight has:

the wisdom to do what is right

the will to make it happen

and the strength to make it endure.

And he suggested the three traits of a warrior are: impeccability, unpredictability, and responsibility. These latter qualities could certainly apply to a writer: impeccability in terms of being conscientious of one’s craft, attending to the details, keeping one’s house in order; unpredictability, in terms of originality of thought, ideas and execution; and responsibility, in terms of what you write, what you choose to bring into the world. These are the qualities we need to summon in ourself as we heed the call to adventure and set off to face our foe. In essence, the Hero is our Higher Self – and writing can help us connect to it (as well as to our Lower Self, our Shadow).

I call these the Avatarian and Atavistic Impulses.

Basically, writing can bring out the best and the worst in us – both in its execution and on the page. Writers can be beasts and saints, charismatic or tedious bores. Good to be around, or the partner/friend from Hell. Selfless, or selfish. Certainly there is an element of selfishness in writing – in indulging in one’s fantasies, as well as in the single-mindedness needed to see a project through to completion; and yet one could argue that in spending precious years slaving away at a manuscript that might have an altruistic element (the edification of humanity!) we are being selfless to a certain extent (although in reality the act of writing is probably a blending of the -less and the -ish!). On the page, the Avatarian and Atavistic Impulses can manifest in the form of characters – we can personify them.

It could be argued that all characters are aspects of the author’s personality (for where else do they come from? who else is writing it?). The Hero and Villain of a tale could be seen as the Higher and Lower Self of the author, although this is perhaps a crude analysis and things are often more nuanced than that. Villains often ‘act out’ our Super-Egos (over-confident, slick, successful, sexually magnetic, etc); and Heroes can often be dysfunctional and even amoral. Martin Amis said that ‘novels come from the base of the spine’ – echoing Nabokov’s ‘tell-tale tingle down the spine’162 – in the way that they explore powerful primal issues around security and identity. They can be an instinctual response to the world, almost beyond cognition – hence the mystery around the creative process, and where authors get their ideas from. Often, we can’t say for certain – until afterwards. The first draft is often written ‘in the dark’ – in the process of unknowing, of seeking, or being ‘driven’ – and the second with the ‘lights on’. The ‘scary thing in the shadows’ disturbs our status quo and forces us to give it voice, and then we ‘wake up and smell the coffee’ (or the stench of blood) and go in all guns blazing. First, Grendel; then Beowulf.

Of Beowulf, the bards sang:

‘And many men stated that south or north,

Over all the world, or between the seas,

Or under the heaven, no hero was greater.’163

When we summon the Hero we are, in a way, evoking our better qualities – our unrealised potential – and giving them a form. There is often an element of wish-fulfilment, of power-fantasy (think of James Bond; Sherlock Holmes; Jason Bourne, etc). The Hero can carry for us all the things we wish we could do or be if only… By writing, we literally tap into these and give them dramatic form; and in the process, we inhabit these qualities. By channelling the archetype, for a while we become it. And this is part of the visceral (as well as intellectual) thrill of writing which is rarely discussed. The adrenalin rush of writing can be intoxicating and … addictive. ‘I feel gripped by something stronger than my will,’ is how Alice W. Flaherty describes it.164

That is why, I believe, writing is the ‘best of me’ (as I tap into my Higher Self) and also when I often feel most fully alive (it can be exhilarating). When I am firing on all cylinders, the writer is a turbo-charged version of myself – I feel like I am stepping into my power and being most fully myself. I am living up to my own potential.

And so by becoming writers, we become in effect, the Hero of our own story. We are no longer the passive recipient of another’s narrative. We have seized control of our own and writing our destiny into being.

Whether we accomplish it is another matter.

The way is littered with perils and pitfalls – not least that of Ego the Giant, who lumbers onto our path and threatens to overshadow the whole proceedings unless he is handled with care.

Next we will look at the Art of Bragging and how that feckless lunk, Ego, can be put to good use.

Extract from ‘The Writer’s Quest’ Copyright Kevan Manwaring 2014

Desiring Dragons: creativity, imagination and the writer’s quest, Compass Books, 2014

December 10, 2014

A Wilderness of Dragons

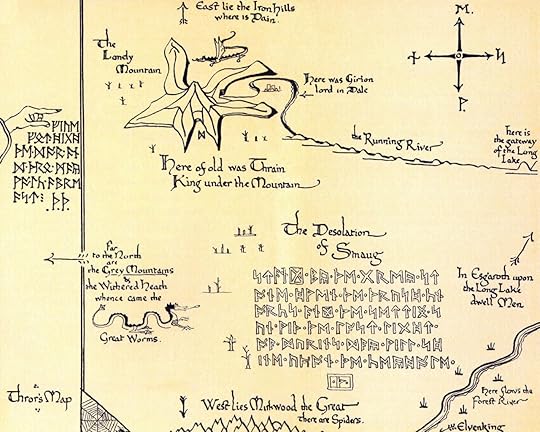

In the eponymous essay, reprinted in The Monsters and The Critics (2006), Tolkien cited the Beowulfian critic Professor Chambers’ phrase ‘a wilderness of dragons’ 298. Tolkien, punctilious as ever when it comes to language, queries the ‘Shylockian plural’, and yet it is clear he would prefer such a hazardous place to the bleak territory of the unimaginative critic. It clearly stuck in his mind, and perhaps acted as grit in the oyster for his creation of the ‘desolation of Smaug’, in the map for The Hobbit (1937) – a blasted wasteland on the edge of the cosy world of the hobbits.

This is a deliberate striking out into unchartered zones.

On the borders of medieval maps, where human knowledge ran out and reason slept, monsters stirred: ‘Here Be Dragons’ the legend read. This is the direct descendant of the primal fear which lurked outside the circle of firelight for our most ancient ancestors. Of course, some fears were very real, when ferocious predators roamed the world with early man. And the fear sometimes remains even when the threat has gone – or wasn’t even there in the first place – the glass ceilings of the mind that keep us prisoners.

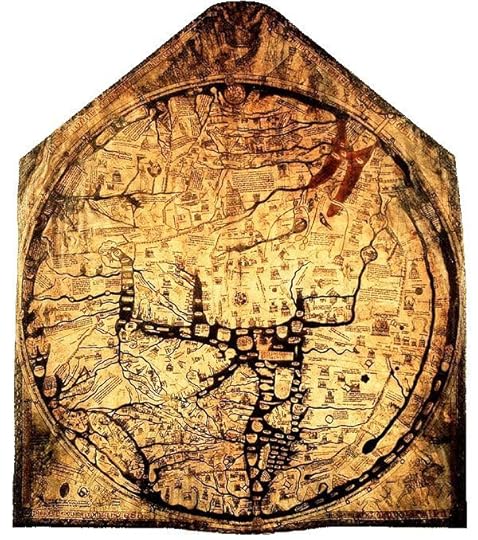

A map is a snapshot of available knowledge. It says ‘this is where we are’, ‘this is how much we know’. It is a circle in the sand with man at the centre. This cartographical solipsism has continued well into the 21st Century, with OS postcode-centred personalised maps; and, on a larger scale, world maps which manipulate the landmass, showing the continents of the Northern Hemisphere far bigger than they should be: the classic North/South divide. A Peters projection depicts the landmasses in correct proportion to the surface of the Earth, and consequently Africa, South America and South East Asia dominate. Other maps depict our ‘Antipodes’, Australia, as the centre of the world, the Pacific Rim, or one of the Poles – a healthy shifting of perspective. Indeed there is no reason why North should be ‘up’ on our maps – we are living on a sphere after all, which doesn’t say This Way Up on it. But we feel, especially in the West, the world revolves around us.

There is nothing new in this.

The miraculously preserved 12th Century ‘Mappa Mundi’ (‘Map of the World’) in Hereford Cathedral, rendered on vellum with its hand-drawn detail looks, to modern eyes, like something out of a Fantasy novel that Tolkien & Sons might have fashioned. The world as we know it is virtually unrecognisable. Like many maps of the Middle Ages, it depicted the Holy Lands at the centre, and Jerusalem at the centre of those. This was and still is for many, the axis mundi of the human universe. The map depicted the whole of Christendom – then, the most successful of religious franchises – what lay outside that belonged to the Devil, that greatest of serpents. In Norse mythology it is the World Serpent who encircles Midgard, the Middle World, biting its own tail like Ouroboros. The dragon dwells where the known becomes unknown: the edge of the conscious world. It is the ultimate threshold guardian – often guarding untold riches, as in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, or in Sigurd and Fafnir, where the monstrous worm – once a covetous brother cursed for slaying his kin – guards a great treasure, Glitaheid: the glittering heath.

Tolkien had this to say on the subject:: ‘I find ‘dragons’ a fascinating product of the imagination. But I don’t think the Beowulf one is frightfully good. But the whole problem of the intrusion of the ‘dragon’ into northern imagination and its transformation there is one I do not know enough about. Fāfnir in the late Norse version of the Sigurd story is better; and Smaug and his conversation obviously is in debt there.’ 299

Dragons have haunted the human imagination for centuries – resolutely defying all probability of their existence. They are the kundalini serpent of the Collective Unconscious; our suppressed desires, lurking in the shadows of the Id; the Smaug Within, grafted to our own reptilian brain. We can no more banish the dragon than we can shake off the coils of our DNA.

These ancient and canny beasts loomed large in Tolkien’s febrile imagination, yet they seem hard-wired into the British psyche – certainly the Welsh and English soul – appearing on the Cymric flag and starring in many folk tales and legends (60 recorded in England300). The most well known, George and the Dragon, about England’s national saint, is only the wing-tip of these, and to this exotic import we shall return, but first let us consider his native cousins.

Merlin, Myrddin Emrys, famously beheld a red and white dragon locked in combat beneath Vortigern’s Tower: he explained that the former were the British, the white, the Saxon – and while they fought no peace would be in the land. Merlin gave his name to the British Isles: Clas Myrddin, Merlin’s Enclosure – he is our tutelary guardian.

In another tale, ‘Ludd and Llevelys’, from the 13th Century Welsh cycle of ancient British oral tales, Y Mabinogi, a terrible scream is heard over the land every May Eve, which blights cattle, causes mares to drop their foals early, women to miscarry and milk to curdle. Llevelys tells Lludd, his brother, how to dispatch them: measure the land, and in its exact centre (which they decide is Oxford – X marking the spot) dig a pit and fill it with mead, covered with silk. This will lure the dragons down, they will drink, get drunk, fall asleep, wrapped in the silk. Then he needs to gather them up, (as they are now in the form of sticky pigs), lock them in a stone chest, and bury them in a hill near Snowdon called Dinas Emrys – where Vortigern’s tower was said to have been and Merlin beheld his two feuding dragons. Thus the stories overlap, biting each others’ tails.

The Lambton Worm and other similar folk tales seem to be morality tales, regardless of their claims to authenticity. There are often local features which ‘prove’ the veracity of the story, as in Worm Rock in Lambton. Beneath the highly stylised chalk figure in Oxfordshire, the White Horse of Uffington, which some interpret as a dragon, there is a conical shaped hill called Dragon’s Hill. It is claimed that the bare patches of earth found upon it were caused by the slain dragon’s blood – highly toxic, like that of the serpentesque Alien in Ridley Scott’s 1982 tech-noir film, which is essential a dragon-in-space horror movie with the message: we take our demons with us.

These, and many others, seem to create a British Dreamtime, with the equivalent of the windings of the Rainbow Serpent – as with the topographical narratives of Aboriginal Australia. Perhaps the large-scale legacy of glaciers in the British Isles suggested this, as they gouged out the valleys and shaped the rocks that stick out like the skeleton of a great land behemoth. With the last glacial period known as Wurm, it is tempting to link this to the being old English for serpent: ‘wyrm’.

Our most famous dragon culture tale is Saint George and the Dragon of course – the ‘pin ups’ of many eponymous pubs, which bear his sign. The dragon had, by this time come to represent the chthonic forces of the unChristian, be they Pagan, Muslim or heretic. The irony is Saint George seems to have started off as a pork butcher from Cappadocia, in what is now modern day Turkey. His grave is situated in Lydda, Palestine – near the area where the story of Perseus, Andromeda and the great Kraken played itself out. Our Saint George similarly rescued a damsel in distress who was going to be fed to the local dragon. Yet lately he gets martyred: forced to walk in red hot iron shoes, broken on a wheel, and immersed in quick lime by none other than Gevya Garsa, the ‘Serpent King’. Saint George’s grave was discovered by Crusaders who adopted him in their campaigns against the Saracen. He was brought home and his Feast Day was chosen as April 23rd, and this eventually became England’s national day of celebration, a reassertion of collective identity. In recent years the English flag – the very same colours the Templar Knights wore – has been re-appropriated as a positive image, out of the hands of the hooligans.

Tolkien’s folk hero ‘Farmer Giles of Ham’ – another kind of ‘pork butcher’ – shows how the chaos-dragon can be subdued by good old English commonsense and stubbornness. In essence, the dragon is any disruption to the status quo. For a full decade from 9/11 the world’s modern Grendel or Chrystophylax was Osama Bin Laden and his Al Qaeda: a useful amorphous bugbear, with countless splinter cells. Like the Hydra of Leda which Herakles fights in one of his Twelve Labours – cut one head off and two more grow in its place: thus, a regenerating supervillain to keep the world’s Stars-and-Stripes-spandexed ‘Superpower’ and his weedy sidekick (e.g. his ‘special friend’, Britain) busy, and feeding the Culture of Fear, for as long as people swallow it. In this way ‘dragons’ can stop the populace from straying too far the white-picketed enclosure and for justifying draconian measures. We live in the Age of the Dragon it seems.

Emblematic of their genre (once used in libraries as a symbol to designate that category) in their overused unlikeliness, dragons have been a staple of Fantasy fiction since the earliest stories, and it looks like there’s no diminishing their popularity: Tolkien relaunched them in modern fiction and they haven’t gone away since – what with the endless Tolkien pastiches (even the anti-Tolkienian, ultra gritty, brutal, and massively popular series ‘Song of Ice and Fire’, by George RR Martin, has them – a whole dragon dynasty). The roleplaying system from TSR, Dungeons and Dragons, have allowed participants to bait dragons in their lairs, and even play them: they come in all shapes, sizes, colours and elements: earth, air, fire and water, bronze, silver and gold dragons. Some have portrayed dragons more positively. German author Michael Ende, in his Fantasy classic The Never-Ending Story (translated into English in 1983) has a luck-dragon (similar to the oriental species – long-necked and whiskered) help the boy hero. American author Anne McCaffrey has made them the key novum of her long-running Dragonriders of Pern series (initiated in 1967, and comprising 22 novels in 2011); a new kid on the block – mega-hyped wünderkind Christopher Paolini – has resurrected them yet again with Eragon, 2003 (first of the Inheritance Cycle): joining the long list of its movie cousins on the big screen: Fritz Lang’s silent double-bill Die Nibelungen (1924); Disney’s Pete and the Dragon (1973); and Dragonslayer (Robbins, 1981); Dragonheart (Cohen, 1996); Shrek (Adamson/Jenson, 2001) and its sequels; Reign of Fire (Bowman, 2002); Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (Newell, 2005); the How to Train a Dragon animation (Deblois, 2010); and the Merlin BBC TV series (2008-2012). The second part of Peter Jackson’s extended Hobbit ‘trilogy’, The Desolation of Smaug (2013) is the latest to flap its wings and breathe fire over the heads of movie-goers.

No doubt more will be on the wing.

It seems many people still desire dragons. We simply cannot take our eyes off of them…

The Spell of the Dragon

A dragon’s gaze was said to be mesmeric – once we fell under it, we were hypnotised and at its mercy. Those who ‘desire dragons’ had better watch out! Dracophilia can become an all-consuming passion, a burning obsession, which can cloud our judgement and drive us to extremes. Tolkien, who knew this fever more than most, describes the hero of The Children of Hurin (2007), falling under the spell of the Fāfnir-like fire-drake, Glaurung:

‘Then Turin sprang about, and strode against him, and fire was in his eyes, and the edges of Gurthang shone as with flame. But Glaurung withheld his blast, and opened wide his serpent-eyes and gazed upon Turin. Without fear Turin looked in those eyes as he raised up his sword: and straightway he fell under the dreadful spell of the dragon, and was as one turned to stone.’ 301

Dragons could be interpreted as symbols of the chthonic forces of the subconscious, which we should bait in their lairs. It is far healthier to assimilate the Shadow than deny it. Jung, who wrote extensively on the Shadow, referred to it as: ‘the thing a person has no wish to be’ 302. Jung defined the Shadow as: ‘…that hidden, repressed, for the most part inferior and guilt-laden personality whose ultimate ramifications reach back into the realm of the animal ancestors…’ 303. Failure to recognise, acknowledge and deal with it led, in Jung’s mind, to problems in the individual, in groups, and organisations. Yet the influential psychoanalysist believed it had positive spin-offs: ‘If it has been believed hitherto that the human shadow was the source of evil, it can now be ascertained on closer investigation that the unconscious man, that is his shadow, does not consist only of morally reprehensible tendencies, but also displays a number of good qualities, such as normal instincts, appropriate reactions, realistic insights, creative impulses, etc.’ 304By embracing the energy of our ‘animal ancestors’ we can tap into deep springs of creativity.

The classic images of a knight struggling in the coils of a serpent seem to represent the armoured identity of the Ego fighting for dominion over the Lower Self: this crops up time and time again in world myths, e.g. Apollo and Python. The serpent is often depicted as being impaled by a spear or lance – in geomantic terms this is the ‘fixing the spot’ of the earth dragon energy. This seems to have been done quite deliberately within Christian temples on pagan sites (the prevalence of St Michael – the dragonslayer – churches on hilltops has been noted by the likes of John Michel, Paul Broadhurst, etc). St Patrick was said to have cast out all the serpents in Ireland from the top of Croagh-Patrick, a mountain on the West coast originally named after Crom-Croagh, the bent-backed one, a chthonic deity vanquished by the usurper priests. The lance, the standing stone, the cross or the spire acts like an acupuncture needle and channels the telluric currents. It is a way of conducting chaos.

There is a sense in which a writer does this every time he picks up a pen, or a musician his violin bow. We tap into the field of potential, give voice to it, craft it. This lateral approach has proved to be very effective, from the Dadaist automatic drawings and writing, to popular self-help books on creativity such as Drawing from the Right Side of the Brain (Betty Edwards, 1983) and The Artist’s Way (Julia Cameron, 1992). It is a rich repository of creativity.

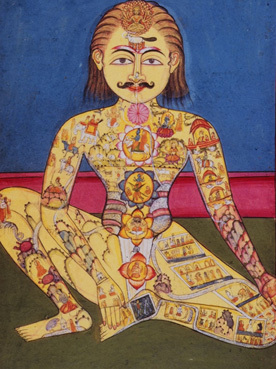

Similarly, the serpent can be seen as the libido, which can be channelled positively – as in the Tantric practice of raising the Kundalini, the serpent energy which dwells in the lowest chakra and snakes up the spine during lovemaking. In the East, the dragon is seen as a positive force, in the human body, in the land. It is worked with in acupuncture and in feng-shui. The Imperial Dragon in Chinese dynasties, and the presence of it in Oriental astrology (as one of the 12 zodiacal signs) shows a qualitatively different status than in the west.

Ophialatry, the worship of serpent deities is prevalent in several ancient cultures. In India the serpent is especially important in Hindu and Buddhist mythology – in the form of the snake god, Nāga; in Voudou the serpent is very important also. Serpent Magic seems to be regaining popularity in the occult circles. As with any sacred knowledge, however, it can be misappropriated, e.g. the Nibelungen Hall (built in 1913), an astonishing serpent temple at Konigswinter, North-Rhine-Westfalia, at the foot of the Seibengebirge range – the seven hills said to have been created by the thrashings of Fāfnir’s tail – depicts a giant serpent interwoven with a pentacle on the floor of a dark shrine to the myth of Seigfried and Fāfnir (the temple is built near the ‘Drachenfels’ – Dragon Rock, the site of a former castle associated with the legend – where Siegfried was said to have slain the dragon and bathed in its blood). Made world famous (and notorious) by Wagner, it was used by the Nazis in the Second World War – a perverted symbol of national pride. These days, it has become a creepy tourist attraction with a reptile zoo, and a ‘Dragon’s Lair’, complete with a long stone serpent, built in 1993 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Wagner’s death.

Generally in the West the idea of the serpent being the Evil One, the seducer, the tempter, is hard-wired into us from an early age. Many people have unnecessary phobias of snakes – exploited by such low-grade schlock as Snakes on a Plane! (Ellis, 2006); and Q, the 1982 monster flick directed by Larry Cohen – a spurious spin on the ancient icon of the Winged Serpent (the Meso-American Feathered Serpent, Quetzcoatl, transposed improbably to New York, in King Kong-like fashion). Yet fear and desire are often closely linked, and what is forbidden often becomes more appealing. The much maligned dragon has gained new fans over the years, and some feel protective towards such unlikely creatures as though they were endangered species. Their very ‘existence’ challenges the consensus reality. And a world which can accommodate dragons can also accommodate heroes, heroines, villains and a whole cast of magical beings. Suddenly the world seems less lonely. The mysterious is possible, and not everything is explained away or tidied up.

Jorge Luis Borges, in his preface to The Book of Imaginary Beasts (1967) calls dragons ‘a necessary monster’: ‘We are ignorant of the meaning of the dragon in the same way that we are ignorant of the meaning of the universe, but there is something in the dragon’s image that fits man’s imagination, and this accounts for the dragon’s appearance in different places and periods.’ 305 The Mappa Mundi is like a retinal scan – around its periphery strange creatures flicker, as in Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood cycle (1984-2009). Monsters and wonders await at the edge of consciousness, at the edge of knowledge, at the edge of the known.British Fantasy author Alan Garner, argues that it is intrinsic to our nature to explore these littoral zones: ‘Man is an animal that tests boundaries. He is a ‘mearcstapa’, ‘boundarystrider’, and the nature of myth is to help him to understand the boundaries, to cross them and to comprehend the new; so that, whenever Man reaches out, it is myth that supports him with a truth that is constant, although names and shapes may change.’ 306 Garner dramatises this concept most directly in his extraordinary 1996 novel Strandloper.

Author Moyra Caldecott, in her memoir, A Multi-Dimensional Life (2007) describes this process: ‘In writing a novel one can play with ideas and concepts that hover on the edge of one’s belief and, while doing so, consider seriously one’s attitude to them.’ 307

This is the liminal territory the Fantasy writer explores. The twilight threshold, where humanity meets the unknown, the Fey, the divine or diabolic – a place we travel to every night in our dreams. Yet the Fantasy writer must be fully awake in this world of dreams, so as not to miss anything. He or she is the lucid dreamer, a Neo of The Matrix (Wachowski Bros, 1999), the one-who-is-awake. In his haunting classic Voyage to Arcturus (1920) David Lindsay has his protagonist Maskull say: ‘I dream with open eyes … and others see my dreams, that is all’.308

In his robust defence of dragons in his influential essay on ‘Beowulf’, Tolkien wrote: ‘A dragon is no idle fancy. Whatever may be his origins, in fact or invention, the dragon in legend is a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold.’309

The dragon is, if nothing else, a potent symbol of the human imagination. The glittering treasure that it hoards could be seen to be the treasures of the subconscious, waiting to be unearthed. By tapping into our own creativity, we are disturbing our own dragon from its slumber. Something old and noble inside us is stirred. Something that has the memory of the Earth and fire in its belly.

Extract from Desiring Dragons: creativity, imagination and the writer’s quest by Kevan Manwaring, published by Compass Books 2014. Available direct from their website here

December 7, 2014

The Monster in the Night

‘Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.’ George Orwell, Why I Write158

The Writer’s Quest begins in uncertainty. As writers about to embark upon our journey (although we do not know it yet) we are often ‘benighted’ – feeling ill-at-ease with life, or maybe outwardly content … except for that little niggle that won’t go away (Tolkien personified this in his charming parable of displacement activity, ‘Leaf by Niggle’). You might not be able to put it into words (yet), but it is the ‘voice that won’t go away’ – even if you cannot quite make out what it is saying, or wants to say at this stage. All you know is – there is something in your life that isn’t being expressed, acknowledged or celebrated. You might be suffering from low spirits, possibly depression – because a part of you is ‘buried’ somewhere. If we want to get shamanic about this (and the creative process shares some intriguing parallels as we’ll discover) then you could be said to suffering from ‘soul-loss’. An essential part of you is missing and needs to be sung back home. That long denied voice – the real you, who has been put to one side while you have got on with the business of life (education; career; family). Parts of you might be engaged in these essential things – but not all of you. And your quality of life might be being affected as a result – manifesting in a certain lingering sadness, malcontent, ennui, or even anger. Something is definitely rotten in the state of Denmark.

But all of that is about to change.

The Anglo-Saxon epic of Beowulf starts in a surprisingly upbeat mood. To summarise the opening section:

After Halfdane, Hrothgar stepped forward to rule the Danes. Under Hrothgar, the kingdom prospered and enjoyed great military success, and Hrothgar decided to construct a monument to his success–a mead-hall where he would distribute booty to his retainers. The hall was called Heorot, and there the men gathered with their lord to drink mead and listen to the songs of the bards.

For a time, the kingdom enjoyed peace and prosperity.

Even if things seem ‘functional’, even successful on the surface, all is not what it appears. There is a ‘long denied voice’ waiting to burst through. William Faulkner describes how: ‘an artist is a creature driven by demons… He has a dream. It anguishes him so much he must get rid of it.’159 In the saga of Beowulf, this is personified as the deformed and tortured figure of Grendel – the very embodiment of a strangled cry.

But, one night, Grendel, a demon descended from Cain (who, according to the Bible, slew his brother Abel), emerged from the swampy lowlands, to listen to the nightly entertainment at Heorot. The bards’ songs about God’s creation of the Earth angered the monster. Once the men in the mead-hall fell asleep, Grendel lumbered inside and slaughtered thirty of them. Hrothgar’s warriors were powerless against him.

The very fact that the songs of the scops, the Danish bards, seemed to enrage Grendel is telling – their eloquence mocks the lack of his own. It rubs salt into the wound of his broken tongue. The voice of the dispossessed (as Grendel possibly is – was he an original inhabitant of the land Hrothgar’s ancestors claimed?); of the marginalised, the disenfranchised, can be fierce. Who likes to be ignored? Or worse – ridiculed, loathed, demonised? You have been so busy with your life you haven’t allowed yourself to listen to this voice. But now it is making itself heard. The monster in the night has come calling, and will not leave you alone.

The following night, Grendel struck again, and continued to wreak havoc on the Danes for twelve years. He took over Heorot, and Hrothgar and his men remain unable to challenge him.

The voice in the shadows has made itself known – terrifying at first, as inevitably it is when the lid is taken off the Id. The subconscious has burst through into waking consciousness – symbolised by golden-gabled Heorot. When our soul-life is repressed, the consequence is often disease, injury, unexpected trauma – our world is turned ‘upside-down’. Our life becomes a ‘nightmare’. We find ourselves captives in a hellish prison – our home has become a charnel house (arguments; bruised silences; divorce; dysfunctional relationships; trouble at work; bills piling up…). We might be driven to drink or other vices, and find ourselves exacerbating the problem – sliding headfirst down a slippery slope. We can feel powerless to stop it – like Hrothgar’s men. It is like watching a car-crash in slow motion. Don’t. Look. This. Is. My. Life. Going. Down. The. Tubes. Whatever we do to attempt to ‘fix it’ fails: talking to friends, therapy, expensive courses, self-help books, holidays, new toys, new partners – the problem does not go away.

All of this can be expressed through the medium of the written word. There is certainly a therapeutic aspect to writing, although one has to be careful. Our catharsis does not easily become the readers unless it is well-crafted. Critical distance is essential to achieve this – otherwise it becomes the mere venting of spleen.

They make offerings at pagan shrines in hopes of harming Grendel, but their efforts are fruitless.

The monster in the night has struck – the idea that won’t let you go, grabbing you with its claws and breathing its hot, foetid breath in your face until you write it down, tell its story. You have been hit by inspiration – although it might not feel it at this stage. No one knows when it will strike. That ‘monster’ – however apparently repugnant – is trying to tell you a message, and it will not go away until you listen. It will continue to manifest in dysfunctional ways unless you give it a voice. Unless you name your demon.

Such beasts raise their frightful heads in myths and legends across the world – often acting as a ‘call to adventure’ for the hero or heroine. In the Welsh collection of ancient tales, Y Mabinogi, a monstrous arm reaches into a stable every night and steals a new born foal until Pwyll, Lord of Dyfed, deals with it. In the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, it is the monster Humbaba – laying waste to the land, which forces the King into action. In the Greek myth of Perseus and Andromeda, it is the Kraken who was causing havoc. In George and the Dragon, a realm is threatened with a dragon which devastates the livestock and land, and is offered a regular human sacrifice to appease it – until the hero rides into town. In the tale of Theseus, it is the half-man/half-bull minotaur who is exacting its deadly tithe on the young men and women of Athens – like an austerity measure of a modern King Minos made incarnate. In other stories, the monster might be less obvious, but equally as terrible. A spell cast over a kingdom. A wicked stepmother or father. The death of one or both parents. A sickening land – The Wasteland. A cruel or ailing king. Tyrants and despots, dragons all. So is the ‘boss from Hell’. Everyone of these ‘dragons’ make life unbearable and forces us to act.

The Danes endure constant terror, and their suffering is so extreme that the news of it travels far and wide.

In the writer’s case, when the ‘monster in the night’ strikes, it is time to pick up the pen – and start writing. Your pen (or qwerty keyboard) is the only thing that will slay the beast. Here, the pen really is mightier than the sword – it is your Weapon of Magic. With it, you begin the Writer’s Quest – plucking up your courage to face this fearsome foe (you wouldn’t be the hero or heroine otherwise). It takes a certain fearlessness to be a writer. To show up to the page. Remember, fortune favours the bold! We have to be like the Fool in the Tarot and step off the cliff, even if the dog of doubt is pulling out our trouser leg. It is a leap of faith, a leap into the dark – but you have no choice.

As with all great works of art – you didn’t ‘choose it’, it ‘chose’ you. It came calling, unexpectedly: trick or treating in your brain. You have gone down with what novelist Michael Chabon calls (after Coleridge) ‘the midnight disease’: ‘The midnight disease is a kind of emotional insomnia; at every conscious moment its victim – even if he or she writes at dawn, or in the middle of the afternoon – feels like a person lying in a sweltering bedroom, with the window thrown open, looking up at a sky filled with stars and airplanes, listening to the narrative of a rattling blind, an ambulance, a fly trapped in a Coke bottle, while all around the neighbours soundly sleep.’ 160

The condition is almost incurable. The only remedy is … to write it out of your system. This might take sometime (possibly years…). It is a daunting prospect that makes most wannabe scribblers break out into a cold sweat and stop dead in their tracks – placing their unwritten book of dreams back in the ‘Might-Have-Been’ Box. You are going to need some true mettle to overcome this particularly beastie – someone with strength, stamina, conviction and unwavering nerve.

Time to summon the hero.

(Extract from Desiring Dragons: Creativity, Imagination and the Writer’s Quest, from Compass Books 2014

December 3, 2014

The Performance of History

I have been attending a series of seminars on New Historical Fiction in the 21st Century, arranged by the Contemporary Cultures of Writing group within the Open University. There were some excellent presentations by academics and writers working within the field and although I have found them overall engaging and thought-provoking I have felt the need to articulate my different view of things here.

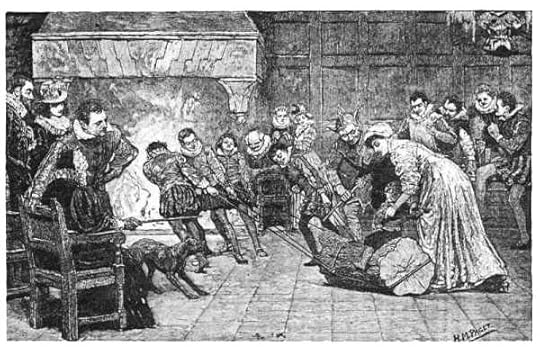

Although there was by no means a consensus in the ideas being presented by the 6 different speakers I did sense there was an unspoken assumption about Historical Fiction which led to a certain narrow iteration of it being discussed. The version of Historical Fiction being presented was largely the one which is an extension of the Modern Realist fiction project – most debates revolved around notions of accuracy and authenticity, as though the historical novel was a BBC Period Drama, rightly praised for its meticulous attention to detail. Although this is an effective strategy for creating verisimillitude and facilitating suspension of disbelief, it is only one in the writer’s tool-kit. Yet it has become normative, and risks perpetuating a kind of safe ‘National Trust’ fiction, Downton Abbey-Lit, if you will. Cosy comfort reading that allows us to step into the shoes of characters from other times for a little while. This style of Historical Fiction is incredibly popular and proves Le Guin’s point that ‘Fake realism is the escapism of our time’ (‘Wizardry is Artistry’, Interview, Guardian Review, 22/11/2014). Although there are some notable exceptions within the genre/marketing category that grip the reader because of their incredible detail and depth of research (Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell soon-to-be-trilogy stand out) there is a prevailing fallacy that history equals realism (what Jerome de Groot called the ‘authentic fallacy’). I wish to argue for a more imaginative treatment of the past. Perhaps if we see our endeavour (as writers of ‘historical fiction’) as the performance of history, then we would free ourselves from the constricting bodices of ‘realism’. This is the crux – how do we choose to portray it? There is never just one way – but many historical fiction novels seem to buy into one consensus reality, the conceit of ‘realism’.

If we consider that every moment immediately becomes the past as soon as it is experienced then we are continually living in a continuum which includes the past and future (everything we experience is future history, and could be material for future writers of historical fiction). If we entertain the notion of ‘the hallucination of the present’ – strip away the walls of time and acknowledge the simultaneity of consciousness – then things become more interesting.

I feel ‘Historical Fiction’ is a flawed category, useful for booksellers, but not for writers or readers. If we saw it in a more porous way, and just tried to write the best fiction we can – then we would circumvent the perils of Heritage Fiction, and begin to write what could be called Heretic Fiction. As the term novel suggests we should be attempting something new each time we sit down to write, not be the literary equivalents of re-enactors (Sealed Knot, etc), trapped in the loop of small pockets of history, fetishizing the material culture of a particular period. Ye Olde Englande forever – perpetuating a reassuringly stable status quo where everyone knew their place, had their role to play, the enemy was clearly identified, and things seem less complicated than the present.

If we look at certain writers who approach history in imaginative ways then we can perhaps start to fashion a new approach to historical literature. First and foremost, I advocate Ivor Gurney – a neglected First World War poet and composer, whose oeuvre expresses an astonishing simultaneity. He is not a ‘historical poet’, but one who uses history in interesting ways. Whilst serving (as a soldier, not an officer like many of the War Poets) in the Trenches he was reminded of his beloved Gloucestershire (resulting in his first collection, Severn and Somme). When he returned home, having narrowly survived a gas attack, he was reminded of the battle-torn terrain of the Front in his Cotswold landscape. Due to delayed neurasthenia he suffered a breakdown and was incarcerated for the rest of his life in a mental hospital. For Gurney, as with many schizophrenia sufferers (and fellow ‘sectioned’ poet John Clare) there was no separation. Gurney’s ‘madness’ was to not to see the walls of time, as most of us tramline our minds to do, only what they separated. His poetry – which expressed this palimpsest – was I feel only partly the result of his shellshock. He could see history side-by-side in his familiar stomping ground, e.g. Crickley Hill, where Neolithic, Bronze Age, Roman, Tudor, and recent archaeology exist in plain sight.

In the work of psychogeographers (WG Sebold; Will Self; Alan Moore; Iain Sinclair; Peter Ackroyd) we see this concatenation of chronologies and polyphonic playfulness. Victorian poet, Walter Savage Landor, wrote a series of ‘Imaginary Conversations’, in which he dramatized conversations between famous people throughough history. Caryl Churchill’s play, ‘Top Girls’, used this conceit to great effect in her play where powerful women from history have a dinner party. Science Fiction and Fantasy writers have been tinkering with history and shamelessly plundering it for a long time. Within the subgenres of Alternative History, Slipstream, Steampunk, Timetravel, and so forth, we saw often original and experimental approaches to the depiction of history, and yet these are seldom acknowledged by respectable academics for whom, along with broadsheet critics, the caste system still exists of ‘Literary = Good; Genre = Bad’. This is being challenged by new waves of Post-post-modernist fiction, and breakdowns in the high-brow/popular culture schism.

Beyond the ghettoisation of genre, fiction should function as fiction. A novel, if it is worth it’s salt, works as a novel, no more, no less. Any historical element is just one aspect of it, but shouldn’t be its governing principle. Human consciousness is not bound by time – as our daily peregrinations through memory, immediate sensation and projected awareness suggest – why should fiction?

December 1, 2014

Another Sun

‘Another sun feeds our life’s streams…’ William Blake

‘Another sun feeds our life’s streams…’ William BlakeHaving survived the feeding frenzy (and media vulturing) of Black Friday, the latest hand-me-down consumer meme from America, we now have Cyber Monday – when it all happens again, online (will the future be merely a digital echo of the present?) and we move even further from the original Christmas message. Whatever your thoughts on ‘Him Upstairs with the Beard’, Peace on Earth and Goodwill to All is as positive, universal and relevant as ever. But Lo! There is nothing in ye olde Xmas message that tells us to buy loads of stuff! We can celebrate Yuletide without being sucked into the consumerism. Yes, it’s hard, but not impossible. Here’s how:

Why not make a pact with your loved ones only to exchange presents that are hand- and home-made?

You can still gather round the hearth and make merry (I’m not advocating an austere, unepicurean experience at all – I’m all for the odd bit of Dionysian sensuality now-and-then).

But …

Allow time for peacefulness (‘stillness’ is what the solstice means after all). Turn off your wifi and all of your devices at least once a day. Try to do something tactile and real – make a loaf, chop logs, go for a wintry walk, soak in a bath, read an actual book, speak to a real person.

Consider those without – buy Charity cards or gifts if you have to, or offer your time. Volunteer locally. Help out at a community project. Make a difference.

Amid the tedious tinsel, looped Carols and forced bonhomie it is easy to forget that for some Christmas is a subdued time of mourning, of remembering. Enforced merriment is a form of emotional aggression. Be joyous, be sentimental, be charitable whenever you feel like it – not just because the adverts tell you to.

Dickens’ fine ghost tale of A Christmas Carol is usually peddled out to guilt-trip potential Scrooges into toeing the line. Anyone display slightly unfestive sentiments is castigated as social pariah, caricatured as the Grinch (showing how even the Satanic Anti-Consumerist can be turned into a profitable trope). Governments continue to insist they do not pay ransoms, but every year we get emotionally blackmailed into buying crap we can’t afford for people who don’t want it.

This year, the orgy of Capitalist excess is made even more obscene (when so much of the world is without) by the use of the First World War Centenary and the famous No Mans Land football game (Sainsbury’s Xmas ad) to sell us the Christmas message. This feels even more of a desecration than the use of the Christian message to sell Amazon warehouses full of sweat-shop shit.

Of course there are other Midwinter traditions – the Pagan, the Jewish, the Norse to name some – and I’m all for connecting with the local, the distinctive, the quirky. Solstice ceremonies, mummers plays, wassailling, carols … whatever floats your boat.

But how about making an early Resolution – an opt for a non-commercial Christmas?

Don’t spend money on loved ones, spend time.

To put things into perspective, here is a poem by the great neglected (in his lifetime) visionary artist and poet, William Blake (whose birthday happened to coincide with Black Friday this year), who struggled all of his life to ‘make ends meet’ but held true to his calling – this is never more poignantly expressed than in this poem, contained within a Letter to Thomas Butts, written 22nd November 1802:

‘My hands are labour’d day and night,

And ease comes never in my sight.

60

My wife has no indulgence given

Except what comes to her from Heaven.

We eat little, we drink less,

This Earth breeds not our happiness.

Another sun feeds our life’s streams,

65

We are not warmèd with thy beams;

Thou measurest not the time to me,

Nor yet the space that I do see;

My mind is not with thy light array’d,

Thy terrors shall not make me afraid.’

70

Let’s change Black Friday to Blake Friday – and celebrate the true wealth of the imagination, without which we are truly impoverished.

William Blake: Apprentice and Master, Exhibition at the Ashmolean, Oxford,

4 Dec-1 March 2015 http://www.ashmolean.org/exhibitions/williamblake/

November 28, 2014

Don’t Worry, Be Appy

Performing at Embrace Arts, 26 Nov 2014. Photo by Adrian Cretu

Performing at Embrace Arts, 26 Nov 2014. Photo by Adrian CretuYesterday saw the launch of two apps featuring Leicestershire writers – resulting from writing commissioned for the Sole2Soul and Affective Digital Histories projects respectively. I was commissioned to contribute writing to both projects, so I made an effort to get to the launch of both events, as it was fantastic to see the culmination of alot of hard-work by alot of talented people: creative, academic, technical.

Falkners Exhibit, Market Harborough – photograph copyright Kev Ryan

Falkners Exhibit, Market Harborough – photograph copyright Kev Ryan[Sole2Soul: ‘wise souls talk to teen souls about shoe soles’]

The first took place at Market Harborough Library. A good crowd of ‘Silver Champions’, (project participants aged over 55) commissioned writers, public, professionals, and well-wishers gathered. Dr Corinne Fowler, from the Centre for New Writing, introduced the event, alongside her University of Leicester colleagues, Dr Ming Lim, Dr Ruth Page, plus LCC library & museums staff and willing assistants. Sole2Soul encouraged writing inspired by Harborough’s Boot and Shoe Heritage, specifically Falkner’s – a long-running family firm in the town. An exhibition in the museum recreates the shoe-shop in loving detail. This fascinating display provided great inspiration for the writers, professional and non-professional alike. My mother worked for Churchs shoes in Northampton, and so I felt an affinity with the theme. I wrote a long poem called ‘Well Heeled’ (see Poetry page on this blog). The event was divided into three spaces – Commissions (performances), Narrate (examples of other writing and photographs), and Curate (where ipads were available to view the Falkners app). At 15 minute intervals a ‘bell’ sounded and we were ushered to the next space. This gave a good overview of the project (and a flavour of the umbrella LCC museums project, ‘Click, Connect, Curate’). It was good to connect with fellow writers, and to talk about what it meant to the Silver Champions and general public. A definite success.

Soul of the City: Affective Digital History

Soul of the City: Affective Digital HistoryCarol Leeming, Kevan Manwaring & Alberto – LCB Depot, 27 Nov’ 14

Afterwards, I dashed back to Leicester, for the Affective Digital Histories launch at the LCB Depot. Although it was advertised to start at 6.30pm, I arrived there (at 6.35pm) just as local legend Carol Leeming finished the performance of her fabulous choreo-poem, ‘Love the Life you Live, Live the Life you Love’! For some reason everything had started alot earlier, which was a bit disappointing. Still, it was a great atmosphere, and I had some great chats with my fellow writers and the App team. A short film was premiered, providing an excellent introduction to the project. Then DJs picked up the vibe, and eventually got us dancing. It felt satisfying to celebrate the success o this fantastic project with those involved – it truly was a team effort. I was tickled pink to see my Marginalia piece viewable on the smartly-designed App. Afterwards, we repaired to Manhattans over the road to celebrate the project and Carol’s birthday – two great reasons for a drink!

Poets in the City: Kevan Manwaring (left) and Adrian Cretu (right) at Embrace Arts, Leicester, photography by Caroline Rowland, 26 November 2014