Kevan Manwaring's Blog: The Bardic Academic, page 35

May 24, 2017

Equinox Bridge

(reposted in memory of the families and victims of Manchester Arena)

Rising to the brightening fields

to the bridge of day and night

when all is in balance

briefly.

Friends, families, dog-walkers, gather

by the quickening stream

united by their mutual awe.

This morning a kingdom

holds its breath,

the day of the new moon,

the day of the Spring Equinox,

the day of the solar eclipse,

the sun entering Aries,

all the usual astrological mumbo-jumbo.

But the solar system is not our personal orrery.

The show is not for us,

although we act like it is.

Not full totality here,

but dramatic enough

for us to stand and stare

astonished,

as the moon takes a bite out of the sun,

Fenris’ rabid bite-marks

raising hackles of primal fear

beyond science and common sense.

Birds quieten, a wind stirs,

pets are bewildered.

Yet we know the light will win in the end.

The moon for once

turns its face away

from the radiance.

A loyal mirror

today is shattered.

Some will turn away from goodness,

some will turn away from the light,

some choose evil’s imagined glamour,

some choose the night.

And yet, in the great scheme of things

(has anyone had a look lately?)

both are needed.

Not a fifty-fifty fixed rigidity

but a flowing, a to-ing and fro-ing.

Like rough-and-tumble cubs fighting.

Towards summer, the lion of sunlight dominates.

Towards winter, a beast cast in night’s bronze.

Both have their place in the Great Dance.

Yet often the light feels frail.

Ah,

so much darkness in the world.

Black-clad barbarians enacting their

impotent rage on aid-workers,

school-children, museum-visitors.

Infantile despots, wanting the world

to comply to their solipsistic

Cyclopean monomania,

their pinhead paradigm,

which perverts its own doctrines

to serve whatever devil lurks inside.

See them nurse their grievance narratives,

polish their Russian rifles,

strap on their home-made bombs,

thinking their lonely library of a single book

can justify destroying all others.

Yet this morning all of that is erased

by the sublime benediction of the new sun,

still shining its endless love on all of its children.

This morning the Earth is like a prayer –

grass, flower, tree: hands raised in praise.

All that lives, that is truly alive,

turns towards the light.

Only that which denies, which deals in

death, in the destruction of its own past,

a Year Zero moronism, does otherwise.

Yet this morning I stand

one foot in the shade

one foot in the light,

between the Horns and the Heavens

a balancing act, a tight-rope walk,

across the Niagaras of positive and negative

moving stubbornly beyond duality.

Beyond a binary world of

with-us or against-us.

I stand poised on Equinox Bridge

knowing as I cross it

that it disappears behind me as I pass,

that it never truly existed

a fleeting moment, a pulse of awareness,

cherry blossom falling on snow.

And somewhere the future

is surging towards us like the swell of the bore.

And somewhere a king

with a black name is buried,

and somewhere Persiled druids

stand posing in the sun.

All bathed in

eight minute-old light

which scatters its photons

magnanimously across the tilting Earth,

the part we call north,

the place we call home.

In the blink of a blind god’s eye.

Kevan Manwaring

Spring Equinox, 2015

(reposted in memory of the families and victims of Manchester Arena)

May 8, 2017

Bard of Hawkwood 2017

Th

[image error]

Centre – Madeleine Harwood, Bard of Hawkwood 2017

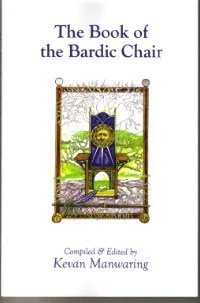

3 years ago I set up the Bard of Hawkwood contest to promote community creativity. This, along with Stroud Out Loud! – the monthly spoken word showcase I founded – offers a way for budding bards to hone their fledgling talents in an inclusive, supportive way. It is not the only way of doing things but it works here in Stroud and the Five Valleys, where there is a wealth of local talent and traditions of artistic heritage, alternative lifestyles, radical thinking, and grassroots activity. The Bardic Chair tradition and revival is something I have explored in my book, The Bardic Chair: inspiration, invention, innovation (1st published by RJ Stewart Books in 200, a new edition of the book is forthcoming).

RJ Stewart Books, 2008

The revival of English Bardic Chairs is largely down to one man, Tim Sebastian. The Arch-Druid of Wiltshire and the Secular Order of Druids. I had the pleasure to know Tim during my time in the city of Bath. I won the Bardic Chair he set up in 1996 (becoming Bard of Bath in 1998). He died in 2007 and the book is dedicated to him. This book, and the others I have written about the Bardic Tradition (Speak Like Rain: letters to a young bard, Awen, 2004; The Bardic Handbook, Gothic Image 2006; The Way of Awen, O Books 2010), as well as my training and experience in Arts in Community Development, inform my endeavours – providing platforms for creativity that celebrate local distinctiveness, diversity, and transcultural empathy. Now more than ever we need to hear one another’s stories and sing the songs of soil and soul.

Here’s the Press Release announcing the new Bard of Hawkwood – feel free to reblog, tweet or share….

The New Bard of Hawkwood Announced

After a gripping contest at the Hawkwood College May Day festival Monday 1st May, the new Bard of Hawkwood has been announced: Madeleine Harwood, who won with her original song, ‘Right Way Up’.

Madeleine said afterwards: ‘I shared the room with some extremely talented individuals and so I am very humbled to have been chosen as this year’s Bard. I look forward to working hard over the coming months to really promote everything the the Bardic Chair stands for.’

The Bard of Hawkwood contest – an annual competition for the best poet, singer or storyteller in the Five Valleys area – was founded in 2014 by Stroud-based writer Kevan Manwaring (a previous winner of the Bard of Bath contest). The theme, chosen by the outgoing bard, Anthony Hentschel, was: Contentment (or Resistance). Each entrant also had to read out a ‘bardic statement’ describing their plans if they were to win. The role lasts for a year and a day.

Madeleine will get to sit in the Bardic Chair of Hawkwood – an original Eisteddfod chair, dating from 1882, kindly loaned by Frampton-based solicitor Richard Maisey, in whose family it has been for generations. It is on permanent display at Hawkwood College. The new bard will get to set the theme for next year’s contest, announced in the winter. Future contestants then have until 23 April to enter an original story, song or poem, and must be able to perform at next year’s Hawkwood May Day Festival.

Kevan says: ‘The Bard of Hawkwood becomes the ambassador for the Bardic Chair, Hawkwood College, and their area. Having been a winner myself I know how empowering it can be – not only for the individual recipient, but also for their respective community. It is about celebrating local distinctiveness, fostering civic pride, and loving where you live.’

***

If you would like to be involved in the Bard of Hawkwood contest, Stroud Out Loud! or creative community in the Stroud area, get in touch.

May 5, 2017

Walking Between Worlds

Practice-based research in writing Fantasy Fiction

(presented at Performing Fantastika, 28 April 2017)

[image error]

‘Roots in two worlds’, Sycamore Gap, Hadrian’s Wall, K. Manwaring 2014

Firstly, to qualify the validity of practice-based research as a core methodology in my discipline, creative writing:

‘original creative work is the essence of research in this practice-led subject’ (‘Creative Writing & Research, 4.6 QAA Benchmark Statement, 2015)

‘Research in or through creative practice can provide a way to bridge these two worlds: to result in an output that undeniably adds knowledge, while also producing a satisfying work of literature.’ (Webb, 2015: 20)

My creative practice extends beyond the page but feeds back into it …

Creative Practice

As a storyteller, performance poet, host of spoken word events and fledgling folk-singer, I have used my creative practice to inform my prose fiction, field-testing material to live audiences. In 2002 I co-created and performed in a commissioned storytelling show for the Bath Literature Festival called ‘Voices of the Past’. In that I performed a monologue as Robert Kirk, the ‘fairy minister’ of Aberfoyle. Little did I know then I was to undertake a PhD with him as a major focus, or that this kind of method-writing was to become a central practice of mine.

An Otter’s Eye View

In his 2005 article on nature writing, ‘Only Connect’, Robert Macfarlane describes the approach of Henry Williamson:

‘Williamson’s research was obsessive-compulsive – writing as method acting. He returned repeatedly to the scenes of Tarka’s story as it developed. He crawled on hands and knees, squinting out sightlines, peering at close-up textures, working out what an otter’s-eye view of Weest Gully or Dark Hams Wood or Horsey Marsh would be. So it is that the landscape in Tarka is always seen from a few inches’ height: water bubbles “as large as apples”, the spines of “blackened thistles”, reeds in ice like wire in clear flex. The prose of the book has little interest in panoramas – in the sweeps and long horizons which are given to eyes carried at five feet.’

‘Only Connect’, Robert Macfarlane, 2005

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/mar/26/featuresreviews.guardianreview33

As a keen walker, my experiential research seeks to experience the equivalent of Williamsons’ ‘otter’s-eye view’: to immerse myself in a landscape, to fully experience it in an embodied way that inhabits me and informs my writing and reveals countless telling details in the process.

As part of my ‘way into’ the world of my novel I have walked long-distance footpaths: Hadrian’s Wall (2014), West Highland Way (2015), Offa’s Dyke (2016), Southern Uplands Way (2017) … walks exploring borders and debatable lands, And I have discovered my enjoyment of singing in the process … While walking WHW solo I started to pick a song each day to keep me going. For the Offa’s Dyke I created a deliberate songbook. These walks gave me an embodied sense of geography, of psychogeography, and plenty of time to think about Borders. Outcomes include a poetry collection, Lost Border; a performance at the Cheltenham Poetry Festival, ‘Across the Lost Border’; a ballad and tale show; and of course, the novel itself.

Spoken/Written

In particular the two worlds of the ‘spoken’ and ‘written’ forms have cross-fertilized most of all in my creative practice and published works (a selection of which are seen here). Since I first started to write poetry, back in 1991, I have straddled these worlds – discovering that the performance of my words (initially at ‘open mic’ nights) was just as important as the writing of them, as a way of ‘getting them out there’, connecting with an audience, gleaning a response, starting a discussion. I soon realized that do so successfully required practise and sometimes a tailoring of the text for performance, focusing on its orality/aurality and factoring in mnemonic devices. I have made a study of these aspects and techniques (and the traditions that inform them) ever since. I collected my field-tested research in The Bardic Handbook: the complete manual for the 21st Century bard, published by Gothic Image 2006. In my folk tales collections for The History Press I rendered into prose fiction a mixture of folklore, folktale and ballad – culminating in the anthology I’ve edited, Ballad Tales. These, in turn, have been restored to orality in subsequent launch events – through either straight reading, extempore performance or song. In storytelling, the ‘performative text’ – not a verbatim transcript but the cluster of phrases, gestures, plot points and tropes the performer holds in their memory (Honko, 2002) can result in a different telling each time. There are many paths through the forest of the narrative, modulated by the feedback loop of performance, audience, performance space, regionality and topicality (‘The Gate’, Manwaring; Gersie, 2012).

The Novel

In my novel I have attempted to dramatize the creative process of cross-fertilization that occurs when song- and tale-cultures are taken to new lands, and sometimes back again: ‘diasporic translocation’. The focus of my research at the University of Leicester, (p/t since September 2014) has been: Longing, Liminality and Transgression in the Folk Traditions of the Scottish Lowlands and Southern Appalachians. After extensive time in key research libraries, the Scottish Borders and North Carolina, I have created the following story: Janey McEttrick is a Scottish-American musician descended from a long line of gifted but troubled women. She lives near Asheville, North Carolina, where she plays in a jobbing rock band, and works part-time at a vintage record store. Thirty-something and spinning wheels she seems doomed to smoke and drink herself into an early grave, until one day she receives a mysterious journal – apparently from a long-lost Scottish ancestor, the Reverend Robert Kirk, a 17th Century minister obsessed with Fairy Lore. Assailed by supernatural forces, she is forced to act – to journey to Scotland to lay to rest the ghost of Kirk and to accept the double-edged gift she has inherited, the gift of Second Sight: the Knowing. Janey, as my performer-protagonist, is the ideal vehicle for exploring notions of world-walking. She is of mixed heritage, being half-Scottish, half-Cherokee – a Meti hybrid, the blood of the Old and New Worlds run in her veins. She is a semi-pro rock musician who becomes, as a result of reconciling herself to her inheritance, a professional folk musician. Her down-to-earth sassiness counterbalances the otherworldly elements she encounters. She is kick-ass but also fallible, gifted but self-sabotaging. A hedonist who needs to learn to reconcile herself to a supernatural reality. Within her she contains the dialectical discourse of my narrative, though if you told her that she’d punch you on the nose.

Digital Performance

Through digital formats, my PhD project explores ways in which the reader ‘performs the text’ in their interaction with hypertextuality. The heteroglossia of my narrative (the voices of Janey’s ancestors, the supporting characters, the antagonist) suggested to me a different way of navigating the text could be more effective than a conventional linear one, and so in creating the ebook version of The Knowing, I tackled the various technical challenges of creating an interactive multi-linear narrative. This involved learning new software and grappling with coding. I created a series of motifs symbolizing the different characters. As metonymic representation was intrinsic to the narrative (the 9 McEttrick Women are connected to through their respective heirloom). Epitomizing the characters with motifs seemed satisfyingly apt and something as an artist I enjoy doing. Embedding these within the text, the reader clicks on the motif if they wish to discover the ‘hidden voice’. Rather than disrupt the flow of the main narrative with these subplots – either through inserted sections, chapters, or footnotes – a small hyperlinked motif enables the reader to choose, thus bestowing upon them the same agency as my protagonists who are all driven by their desire to know in some way. This chimes with the conceptual underpinning of my novel as an epistemological enquiry: what do we know? How do we know what we know? Why is some knowledge valued above other kinds? Can we ever know another, or even ourselves, fully? Can any knowledge be ‘solid state’ in certainty, or does objective truth disappear into contradictory details the closer it is examined? In a ‘Post-Truth’ age of Trumpian fake news, such questions seem timely (although I suspect they are perennial – such questions have been haunting critical thinkers for a long time). But to return to the notion of reader-performer: any readers ‘performs their text’, in reading of a line, the turning of a page, and the transforming of marks into meaningful narrative, but in an ebook with multiple pathways that performance seems more explicit (though paradoxically less physical). I liked the idea that each of my links is a kind of portal (a digital wardrobe to Narnia or a rabbit hole to Wonderland) taking the reader to another paradigm. The ebook makes the reading experience an acting out of the classic ‘Portal Quest’ Fantasy (Mendelhson 1999), although in truth any book can provide a trapdoor in reality. Recent works such as Iain Pears’ Arcadia (2016) augment those portals with apps and websites, but any reader with sufficient imagination can provide their own – whether through daydreaming, drawing, fan fiction, cos-play, gaming and so on. Initial Reader-Reception of the ebook has so far been encouraging:

‘this novel has an appealing plot and uses digital media in a clever way to bring other voices into the main narrative.’ Everyboy’s Reviewing [accessed 25.04.17]

‘Like the Fey and the plot, the e-book itself is full of cunning entanglements.’ Amazon.com review [accessed 25.04.2017]

‘The use of links within the ebook text to jump between narratives gives a real sense of the narratives being separate and ongoing outside what is written, while not detracting from the flow of the novel itself. It’s an interesting use of the technology that works really well in what it sets out to do: to give the reader the choice of reading the initially hidden narratives or to allow them to read the main narrative and then the related narratives afterwards. I feel the choice of the reader mirrors Janey’s choice to read Kirk’s Journal or not; it gives the reader a little taste of what Janey herself faces when she receives her ancestor’s contraband form of communication.’ Good Reads review [accessed 25.04.2017]L

Live Lit

One byproduct of my PhD research has been the ‘ballad and tale’ show called ‘The Bonnie Road’, a one-hour blend of storytelling, song, and poetry co-created with my partner, the folksinger Chantelle Smith, which draws directly upon the supernatural Border Ballads of Thomas the Rhymer and Tam Lin, and my research into Scottish folk traditions. This illustrates how it is possible to turn elements of a novel into a ‘live lit’ experience, one that is co-created with the audience in a slightly different form every single time due to the extempore style of delivery. It has been performed at festivals, small theatres, pubs and gatherings. Bringing alive the characters in the two ballads: (Thomas the Rhymer; Tam Lin; Janet; The Queen of Elfland) in some cases acting them, was an effective way of getting under their skin and finding a ‘way in’. Embodied insights which deepen my understanding of them, nuancing my depiction of them in fiction. This was augmented by a workshop I ran called The Wheel of Transformation in the US and UK in which participants role-played those 4, sometimes swapping roles and genders.

Feeding Back into the Novel

All this ‘research through practice’ has enriched my visualisation of the novel and deepened understanding of the characters. The response from the audience, discussion generated and comments garnered have helped create a fertile feedback loop. Furthermore, my archival research has discovered fascinating details (marginalia in the notebooks; poems; diary entries) which have been directly fed back into the novel – in characterisation and plot, which you can read about on my Bardic Academic blog [eg ‘The Remarkable Notebooks of Robert Kirk’].

Pushing the Boundaries

The Knowing has attempted to push the boundaries of both form and content – finding fertile ground in the creative tension between the Actual and Imaginary, as Nathaniel Hawthorne terms it (‘The Custom House’, introduction to The Scarlet Letter). I argue that true Fantastika lies within the negative space of these apparent extremes. I certainly choose to pitch my flag in this liminal zone where the magical and the mundane rub shoulders, finding neither straight realism (so-called mimetic fiction) or high fantasy to my taste. I have dramatized this transitional space as ‘The Rift’ within my novel, a place between the Iron World of humans and the Silver World of the fey – ever-widening after the cataclysm of the Sundering, when the Borders were sealed. Yet in my novel there are irruptions on both sides: characters and contraband slip through; and in the Trickster figure of Sideways Brannelly, a 19th Century Ulster-American who has become a ‘Wayfarer’ – a trader between the worlds – I have someone who acts out the synaptic cross-fire between these hemispheres. He smuggles the lost journal of Robert Kirk out from Elfhame, metaphorically mimicking the production of the actual text itself – the result of my own walking between the worlds. And in my career as a writer-academic I continually straddle the apparent ‘creative-critical’ divide, finding it a place of intense creative generation – a mid-Atlantic ridge for the black fumers of my mind!

Full Circle

My practice-based research continues to inform my writing. And in author events such as book launches (eg Steampunk Market, Chepstow, 22nd April) the ‘performance’ aspect comes full circle, as I sometimes ‘role-play’ characters from my novels (in this case, my Edwardian aviator Isambard Kerne from The Windsmith Elegy) to bring alive the storyworld for the casual browser, enticing future readers to ‘walk between the worlds’.

Notes:

Gersie, Alida, et al, Storytelling for a Greener World, Stroud: Hawthorn, 2012

Hawthorne, Nathaniel, ‘The Custom House’, introduction to The Scarlet Letter, 1850.

Honko, Lauri (ed.) The Kalevala and the World’s Traditional Epics, The Kalevala and the World’s Traditional Epics, 2002

Macfarlane, Robert, ‘Only Connect’, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/mar/26/featuresreviews.guardianreview33 [accessed 25.04.17]

Manwaring, Kevan, The Bardic Handbook, Glastonbury: Gothic Image, 2006

Manwaring, Kevan, Oxfordshire Folk Tales, Brimscombe: The History Press, 2013

Manwaring, Kevan, Northamptonshire Folk Tales, Brimscombe: The History Press, 2013

Manwaring, Kevan, Ballad Tales: an anthology of British ballads retold, Brimscombe: The History Press, 2017

Manwaring, Kevan, The Knowing – A Fantasy, Stroud: Goldendark, 2017

Mendlesohn, Farah, Rhetorics of Fantasy, Wesleyan University Press, 2008

Pears, Iain, Arcadia, London: Faber, 2016

QAA Benchmark Statement (draft) 2015

Webb, Jen, Researching Creative Writing, Newmarket: Frontinus, 2015

May 4, 2017

Wild Writing & Free-range Teaching

First published in Writing in Education Summer 2016

[image error]

Writing by the shores of Loch Maree, Highlands, Summer 2012

Imagine turning up to a lesson with no notes, no lesson plan, no ‘learning outcomes’ – just your years of experience, skills and writer’s imagination? By adopting a more fluid, sensitized, reciprocal approach (akin to what Philip Gross describes as ‘the discipline of indiscipline’ 2006) you, the lecturer, become the author of the moment. The act of creativity is restored to the classroom. The frisson of risk electrifies the process, as with one’s actual writing practice, when, in those precious hours snatched from the demands of the week, you sit down to do some of your own writing. Yes, you do the research, you make your preparations, but when you turn up at the page or the screen to write something else happens: a different part of the brain engages – a lateral process takes over. If we wish to authentically offer our students genuine techniques or practices, one’s we use ourselves in our craft, then where better than to start with this – the white heat of the moment –– when anything may emerge? As a writer it is this moment when I am freest and most fully alive. There is a sense of being an explorer in an undiscovered continent. This is the quality I wish to bring into the classroom. As Stephanie Vanderslice suggests, ‘it is more important than ever to draw back the curtain on the wizard and show undergraduates the many invention tricks writers rely upon to get started and to keep the well of inspiration at an optimum level.’ (2011: 32)

Alas, teaching (of the ‘factory farming’ kind: I’ve personally found this worse in FE than HE) can seriously debilitate the creative aquifer. Schemes of work … Lesson plans … Set texts … Assessments … The structures of creative writing as a taught discipline can stifle the very thing they are trying to nurture – resulting in exhausted, demoralized lecturers (as informal conversations at conferences suggest and the strikes of 2016 attest) and uninspired, disengaged students (re: the dreaded Student Survey). In this article I argue for a possibly radical approach (accepting that any writing teacher worth their salt probably uses some form of ‘wild writing’), but one that can still work in tandem with existing pedagogical systems. There is a place for the lecture, the seminar, the practical focus of a workshop, tutorials, assessment … for hard pedagogy – but also, as I would call it, for wild writing (following in the spirit of Roger Deakin’s ‘wild swimming’ (2000) and the other analogous activities his approach inspired). Wild writing empowers both the lecturer and students. It credits teachers with intelligence and resourcefulness. Wild writing encourages us to take risks, to go beyond comfort zones and familiar ways of doing things.

Although wild writing is a practice I have been intuitively cultivating all of my writing life – a cross-fertilisation of my storytelling, creative writing and teaching skills, I first articulated it as a practice when I was invited to North America in September 2015 to offer some workshops privately to a small group. Wild writing spontaneously happened as we toured Rhode Island and beyond. One time, a scintillating cove inspired some ‘reflections’; another time, it was the site of an old fun fair which unearthed long-buried emotions and memories. However, I will focus on the experience of devising my ‘Wild Writing’ class, which took place at Hawkwood College, Gloucestershire, in the Spring term of 2016. In doing so I do not wish to be prescriptive, but at best inspirational – so I won’t be offering detailed activities – for the very spirit of wild writing is to be in the moment, to draw upon the actuality of the workshop, the resources and experience of the group, and your own ingenuity. This accords with what Harry Whitehead describes as a praxis of ‘nomadic emergence’ (2013).

Faced with the relentless treadmill of teaching – my life measured out in Tutor-Marked Assessments and coffee spoons, writing workshops and marking – my original motivation was to devise a way of breaking free of this cycle and reinvigorate my pedagogy. If I am bored the students will be too. Rather than regurgitate the usual saws about using notebooks, showing not telling, et cetera – which can be found in numerous books, blogs and MOOCs – I wondered what new approach I could offer based upon my actual practice as a writer? My USP, to use that hissing serpent of a marketing term. I don’t want to be a Mr Potato Head teacher: change my distinguishing features and I could be saying the same as anyone else. The best teachers, the ones you remember, are always the ones who do things differently. Who break the rules in some way, even if it’s just in their ‘manner’. My favourite English teacher at school, Mr Alsop, would at the drop of a hat, sound off about his pet subjects: Rugby and Bruce Springsteen. His droll delivery was reminiscent of the late comedian Mel Smith. Somehow, through his raconteur genius he enthused the class with his love of literature. We enjoyed his class and so we paid attention. He engaged our interest. And there was a frisson of unpredictability about his lessons: that we could go ‘off-piste’ at any moment.

Play is an often forgotten element of learning, but one that the poet Paul Matthews advocates: ‘Writing can become very intense and inward at times, so play and laughter (as well as tears) are a vital part of any group work.’ (1994:7)

As I was teaching two Open University modules (A215; A363) and another Adult Education evening class locally on novel-writing, I wanted to try something different, something less technical and more spontaneous. This not only provided a personal ‘call to adventure’ to my own pedagogical ingenuity, it actually helped as a counter-balance to the other classes I taught. As I put it to a friend, one approach was ‘Apollonian’, the other ‘Dionysian’: left-brained and right-brained, if you will; although such crude demarcation of our mind’s complexity is flawed – a false dichotomy – as Gilchrist (2012) and others have demonstrated. The two approaches, the creative and the critical, cross-fertilise in the best workshops and writing practice – but for now, as an experiment, I wanted to separate the methodologies and see what would happen.

The first half of my week was dedicated to traditional pedagogy, but my Wednesday night ‘Wild Writing’ class became something I actually looked forward to: a safety valve from the assessment-focused pressure of the week. A chance to take a different approach; to turn off the SATs-nav.

Unlike my other classes, I deliberately did not devise a scheme of work for my wild writing workshops. I did only the vaguest of lesson plans – a hastily-scribbled idea which would emerge on the day of the class, usually while out ‘wild-running’ in my local woodland, allowing the birdsong, running water, sun-dappled shade, and green work its magic on my consciousness. Rather than forcing a theme or an activity onto the page or screen, I would allow things to emerge – by simply being fully present in a natural environment. Taking a leaf from WB Yeats’ ‘Wandering Aengus’, I went out to a hazel wood… Soon the fire in my head was lit.

In the first session I explained my ‘anti-outline’ – each week we will see what emerged. I might have a few prompts up my sleeve, just in case, but I was determined that the workshop would be an organic emergent process. To break the ice, I got everyone to give themselves a ‘wild’ epithet, an alliterative one which provided a useful mnemonic. This also encouraged them to ‘inhabit’ the wild paradigm, to feel the wildness inside themselves. I read out the course blurb, to focalize:

Are your words too tame? Your thoughts too feral? Do your ideas need liberating? Let them out of the cage, and allow them to prowl the page! This rule-breaking writing workshop is designed to encourage you to explore the untamed fringes of your desires and fears, to express that inner howl, to give voice to that long-denied cry. You’ll be supported in a friendly, safe environment to venture beyond comfort zones and tap into words that can electrify, shock, motivate and move. All you need is a pen and paper and a willingness to be wild!

I asked them to come up with their own definitions of ‘wild’ – writing suggestions on Post-its, and sticking them on the board. They came up with:

Raw

Unfettered

Free

Sensual

Vulnerable

Uncensored

Secrets

Passionate

Spontaneous

Edgy

Nature

Embodied

Fear/less

Landscape

Deep emotion

Out of the box

Undefined

Pure

Untamed

Energy

Down to Earth

From the unconscious

Climate

Nonsensical

Life going wrong

Experiential

Abstract/extreme

This was a promisingly wide-spread demarcation of territory. A freewrite on the theme also bore fruit – the very nature of that practice lent itself to the prompt perfectly. The best freewrites are of course ‘wild’, that is ludic, non-linear, exploratory, transgressive, and syntactically feral. In the spirit of Natalie Goldberg, I encouraged my students to ‘lose control’ (1991:3).

The first lesson’s emergent theme was summed up by this in-the-moment acronym: SOAR (Sensuality; Observation; Awareness; Reflection), something of an OCD of mine! Being fond of creative acronyms and aware of the potential can of worms I was opening I created a ‘safety net’ for the workshops using my principle of MAC: Mindfulness; Autonomy; Confidentiality.

Mindfulness: being aware of the potential impact of what you are sharing. Not to censor yourself, but if the writing contains strong language, disturbing imagery, controversial elements, et cetera, just to let people know.

Autonomy: you always have the choice about what you share. No one is expected to share, although everyone is encouraged to do so at least once in the workshop.

Confidentiality: what is shared within the workshop is confidential. If you wish to share or discuss your own work outside of the workshop that must be your choice, but respect the privacy of others.

I also emphasised that the wildness should be focused on the page, and usual workshop etiquette applied. For such a class it was essential that ‘strong container’ was created to hold the participants in their process. My wish was to encourage my students to go beyond their comfort zones (in their writing). To try out new forms or genres. To go to the edge of what they think they ‘can’ or ‘should’ say, what they might be ‘allowed’ to write about. To inject their writing with some adrenalin, with strong emotions, with a bold, embodied voice. To have the courage to show up to the page and to face its nullifying whiteness, to shatter its silence, and defy those negative voices which might have inhibited in the past. As Whitman put it in ‘One Hour of Madness and Joy’: ‘O to have the gag removed from one’s mouth’ (1959:80). In response to my suggestion to recite this poem of Whitman’s out loud, outside, a student responded: ‘Just what I needed to shout right now. Thank you.’

Over the ten weeks I tried a range of approaches, using not only the usual examples of writing (‘wild writers’ such as Emily Dickinson, Mary Oliver, DH Lawrence, John Clare, Ivor Gurney, Gary Snyder, Nan Shepherd, Robert Macfarlane, Ted Hughes, Helen MacDonald, and Henry Miller) but also different media and methodologies. Beyond the usual triggers of art, music, movement and objects that any creative writing teacher might draw upon I tried out the following: Using different approaches to handwriting (writing without looking at the page; writing in different directions, e.g. from the edges of the page inwards, across the margins); Using what arises (my experience of storytelling has taught me to use whatever arises as part of the performance, so, if a phone goes off, include it in the oral narrative. I applied this approach to each session. If we were interrupted, e.g. by a fire alarm test – I saw it as a gift. A news item, or the weather – anything may trigger a creative response). The details here are not as important as the general approach: be wildly inventive. What I deliberately did not do was draw upon my usual repertoire of creative writing resources – my tried-and-trusted handouts, my go-to activities. I did not want to be teaching on auto-pilot. This forced me to invest creative energy into the actuality of the workshop – what I love doing best. This is when I feel I am firing on all cylinders as a teacher – plucking ideas, quotes, activities and approaches from the air. Not as a micro-managed teaching drone. As Freire puts it, rather than being the ‘anti-dialogical banking educator’, focused on recruitment, retention and results, I wish to emphasize the ‘dialogical character of education as the practice of freedom’ (1996: 74). Student and teacher should enter into a porous space where learning can happen in any direction – where both parties can feel a sense of creative liberty within the classroom, as sacrosanct as the white page or blank screen.

Student Writing

Much of what was written in class was ephemeral by nature – composed quickly in response to a prompt, shared fresh from the notebook, and then ‘let go of’ like Buddhist sand mandalas. A few pieces were brought in the following week after being worked on at home (e.g. the prompt to ‘write about a wild time’, triggered a visceral, kinetic piece of life-writing about seeing a punk band as a student in the 70s – something the student hadn’t thought about ‘in years’). The emphasis of the workshops was on process more than polished ‘artefacts’, but here is a smattering to give some idea:

Shooting Crows

I watched a man shooting crows.

I felt the recoil and fall.

I teased apart the feathers

and the little cracked hearts for answers.

All I found was the finish,

the filth and the spore.

There’s no meaning in dried eyes.

The resting of the carcasses

in the field down by the burn

where the ducks nested;

the sorrel greened on the blood.

Student 1 Prompt: write about the natural world.

Elephant in the Room

In our room there’s a jade green hippo

with carving knife teeth in a man-trap jaw

Baleful eyes bubbling from the brown

sluggish river of sewage and mud

Submerged in slurping bellicosity

it’s poised to drown me in the sloppy miasma

and amputate my manhood

Give me an elephant in the room

any vindaloo Taj Mahal tiffin

with trumpet voluntary to welcome me,

an embracing trunk to snuffle my neck

and never to forget we’re lovers

It would sprinkle me with cool paddy water

Whilst we swayed through orchards of pink mango

Student 2 Prompt: Write about something extremely improbable.

‘You want wild words’

You want wild words

Man made creations

Tamed by the intellect

I will show you wild Ness

In her bare foot bare faced

Nakedness

crouching low amongst the

Dank rotting earth

Student 3 Prompt: What does wildness mean to you?

Skep Skin

A hive in my hand

honeycomb hollow

oozing nectar

golden energy

gathered again and again

a lifetime’s work

in a teaspoon

stir into your tea

consciously

soothing the raw edges

of the day

sweetness delivered

by black and yellow drones

a sticky note

from the flowers

a souvenir of the sun

summer on the wing

an orchard on my tongue

Student 4 Prompt: write about what’s in your pocket right now (a small tin of Burt’s Bees handsalve).

Conclusion

I found running my wild writing workshop one of the most interesting and rewarding things I have done in recent years in terms of my teaching. As in all teaching I learnt just as much in delivering it as I hoped my students did in experiencing it. It was a continual learning curve which forced me out of any kind of pedagogical complacency. It was challenging and engaging in the right places – making me re-evaluate everything I usually do in a writing workshop.

From my experience of running these workshops, I would advocate the following: include a ‘wild writing’ hour in your weekly schedule – it’ll be good for you and your students. Suggest it your department: see what happens. Get out of the classroom – take your group into nature and write ‘on the hoof’. Allow yourself to go to the edge of your practice, of your writing, explore those uncomfortable places, give voice to the shadows, the songs of the maniacs:

He who approaches the temple of the Muses without inspiration, in the belief that craftsmanship alone suffices, will remain a bungler and his presumptuous poetry will be obscured by the songs of the maniacs. Plato (Flaherty, 2013: 63)

Institutional bureaucracy is inevitable, but when it actually impedes teaching and, as a result, impacts upon the sacred cow of ‘student experience’, then it must be questioned. Common sense would surely suggest that we only use systems that support what it is we are trying to do, rather than force ourselves into straitjackets that over-complicate, dessicate and demoralize. In recent years much has been written about the debilitating tendency in universities to focus on the financial aspects of the process (Warner, 2015). This mindset is counter-productive to the quality of teaching and research. Students are expecting guaranteed results as the pay-off of their ‘investment’. As student satisfaction is the gold standard that we are now beholden to, there is a worrying trend which those in HE are all too aware of (the thing that should not be spoken): reducing standards to ‘please the students’, because they ‘pay our bills’. Although I haven’t had to do this myself … yet … the notion appals me. When we compromise standards for the sake of student retention and satisfaction something is deeply-flawed. The baby has been thrown out with the bathwater. Surely we need to be less goal-driven and target-focused? The best writing does not emerge through narrow commercial imperatives or through a checklist of techniques, a dry naming of parts. We must create a culture of learning, knowledge, open-mindedness, exploration, and invention. Wild writing could be a small part of that: an oasis of creativity for creativity’s sake, mutually enriching to teachers and students.

NOTES:

Deakin, R. (2000) Waterlog: a swimmer’s journey through Britain, London: Vintage.

Flaherty, A.W. (2013) The Midnight Disease: the drive to write, writer’s block, and the creative brain, NY: Mariner Books.

Freire, P. (1996) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, (Trans. Myra Bergman Ramos), London: Penguin.

Goldberg, N. (1991) Wild Mind: living the writer’s life, London: Rider.

Gross, P. (2015) ‘A Walk in the Abstract Garden: how creative writing might speak for itself in universities,’ Inaugural lecture, University of Glamorgan, 10 December 2006, published in Writing in Practice: 1. http://www.nawe.co.uk/DB/current-wip-edition-2/articles/a-walk-in-the-abstract-garden-how-creative-writing-might-speak-for-itself-in-universities.html [accessed 11.06.2016]

Matthews, P. (1994) Sing Me The Creation: a creative writing sourcebook, Stroud: Hawthorn Press.

McGilchrist, I. (2012) The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Yale University Press.

Miller, James E. (ed.), (1959) Completed Poetry and Selected Prose by Walt Whitman, Jr, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Vanderslice, S. (2011) Rethinking Creative Writing, Ely: Frontinus.

Warner, M. (2015) ‘Learning My Lesson: Marina Warner on the disfiguring of higher education’, London Review of Books, Vol. 37, No. 6.

Whitehead, H. (2013) ‘Nomadic Emergence: Creative Writing Theory and Practice-Led Research,’ in New Ideas in the Writing Arts: Practice, Culture Literature, edited by Graeme Harper. Cambridge: CSP.

Many more titles were used during the development and delivery of these workshops. For an extensive reading list of Wild Writing titles, or to offer suggestions or comments, contact Kevan: km364@le.ac.uk

Kevan Manwaring is a Creative Writing PhD student at the University of Leicester (Supervisor: Dr Harry Whitehead). Since 2004 he has taught creative writing for the Open University and is a Fellow of Hawthornden, The Eccles Centre for North American Studies (British Library) and the Higher Education Academy. He has co-judged The London Magazine annual short story competition and won an AHRC Essay prize for ‘The (Re)Imagined Book’. In 2015 he was a consultant academic for BBC TV’s The Secret Life of Books. He blogs and tweets as the Bardic Academic.

Wild Writing is currently running at Hawkwood College (May 2017). Limited places are available. Book here: http://www.hawkwoodcollege.co.uk/courses-and-events/arts/wild-writing—kevan-manwaring

April 17, 2017

The Illustrated Novelist

The Illustrated Novelist

Illustrations based upon Robert Kirk’s 17th Century notebooks by Kevan Manwaring, The Knowing, 2017

I have long been an appreciator of illustrated text. Being a writer coming from a Fine Art background, this is perhaps not surprising, as I enjoying doing both – playing with words and images in my stories and drawings – revelling in the incredible freight and flexibility of letters and the infinite potential of the line, the mark.

[image error]

Motif for ‘Bethany’, K. Manwaring, The Knowing 2017

From Palaeolithic cave art onwards we have illustrated our lives, representing symbolically our fears and dreams, our gods and demons, or simply the miracle of our existence: the handprint that says I am here, I exist, I belong. We have used art to express what is significant to us. For a long time art was used to express the Divine, but also to make sacred narratives relatable: in exquisite illuminated manuscripts, in beautiful Books of Hours, in the stained glass windows of medieval cathedrals, in the illustrations of canonical texts. Of course art was also used to convey power and status, in the iconography of heraldry, coats of arms, portraits of the wealthy and what they owned: landscapes were as much about who owned them as what they contained. The frame did not simply delineate the edge of the picture, it implied ownership, the border of privilege, the ha-ha divide between the haves and have-nots.

[image error]

Motif for ‘Molly’, K. Manwaring, The Knowing 2017

With the printing press came a new democracy that allowed, ultimately, art and text to be read, shared and owned by all sections of society. The first illustrated books were still the luxuries of the elite, but as printing presses became more efficient and economical handbills, chapbooks and broadside ballads started to be disseminated from street-corners, often with crude, but thrilling illustrations recycled for different contexts – a new song, the latest scandal, a bloody execution. Penny Dreadfuls and illustrated newspapers fed the public’s appetite for text and image. The comic strip, commonly a syndicated three-panel trick, was born. It developed into the comic book and the so-called graphic novel, now glossy full-colour affairs – largely the flagships of lucrative franchises (with shining exceptions) – but when I started reading them, they were black and white weeklies, printed on newsprint quality paper, costing a few pennies and often seen as ‘throw-away’. Fortunately I realised their worth and avidly collected them, building up my own personal library.

[image error]

FBI motif, K. Manwaring, The Knowing, 2017

My love affair with comics lasted for a couple of decades, and for a while I had ambitions to become a writer or illustrator of them, but I developed a taste for more sophisticated texts, while not losing my enjoyment of illustration. My own idiosyncratic exploration of this form has led to personal favourites: the luminous ‘songs’ of William Blake; Aubrey Beardsley’s La More D’Arthur; Gustav Doré’s Paradise Lost, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and Don Quixote; illustrated Fairy Tales, especially the work of Arthur Rackham; John Tenniel’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass; the magnificent editions produced by William Morris’ Kelmscott Press; and later, the Hogarth Press – John Stanton Ward’s Cider with Rosie. The simple charm of Antoine de St-Exupery’s The Little Prince; Mervyn Peake’s fabulously grotesque Gormenghast trilogy; Tolkien’s self-illustrated The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Then, as my tastes developed I fell in love with the watercolours of JG Ballard’s The Drowned World (Paper Tiger); the nightmarish art of Dave McKean (who as well as providing the cover art for Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, also collaborated with Iain Sinclair of tomes such as Slow Chocolate Autopsy); Hunter S Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas would not be the cult classic it is without the wild art of Ralph Steadman; Patrick Ness’s A Monster Calls for me will always be the defined by the art of Jim Kay; Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, by the intricate motifs which emulate those of Lyra’s golden compass, the Alethiometer. When I read Neil Gaiman’s Stardust, it was Charles Vess’ illustrations which enchanted me as much as the story. It created a certain aesthetic, evocative of Victorian classics, as did Michael Chabon’s Gentlemen of the Road, a homage to the adventure novels of Rider Haggard and Conan Doyle. Visual ‘furniture’ has been deployed in fiction since experiments in the novel form began – it is there in Laurence Sterne’s 1759 Tristram Shandy with its blacked out pages, in Daniel Z Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000), and can be found in books as recent as Iain Pears’ Arcadia (which uses an app with visual representations of narrative pathways) and Naomi Alderman’s The Power (both 2016). I knew I would always revel in these paratextual elements.

[image error]

Motif of ‘Clarence & Constance’, The Knowing 2017

And so it is small wonder that I decided to incorporate them into my PhD novel project, The Knowing – A Fantasy. This decision was influenced by not only my lifelong ‘guilty pleasure’ but by archival research. Upon examining the primary source material of Robert Kirk, the ‘fairy minister of Aberfoyle’, I discovered within his notebooks remarkable illustrations (see my blog on ‘The Remarkable Notebooks of Robert Kirk’). Kirk also owned an exquisitely illustrated Book of Hours. Discovering the fact that the young Kirk was prone to doodling not only ‘humanised’ him, it also revealed the workings of his subconscious – a gift to a novelist attempting to bring him alive. He became more than just a formidable minister of the Presbytery, he became flesh and blood. By copying his artwork, mark by mark, I felt as though I was slipping into his skin.

[image error]

Motif of ‘Margaret’, Robert Kirk’s 2nd wife, K. Manwaring, The Knowing 2017

And so, inspired by this, and by creative decisions around how to best present a multi-linear narrative, I decided to create a series of motifs to represent the different ‘voices’ within the text. These will provide signposts for the reader, to help them navigate around it. In the e-book version, by clicking on the embedded motif you can be taken to the ‘side-text’ (if you wish); then, when you’re done, you can return to the main text by clicking on the plectrum (which represents my main character, the musician Janey McEttrick). On our computers and phones we are used to using similar icons in the form of apps and tiles on our desktop. An unobtrusive motif can adorn a block of text like an illuminated capital in a manuscript, and it is up to the reader whether to explore or not. This feels like a more elegant solution than footnotes (which threatened to overwhelm the otherwise marvellous Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrel), and I liked the idea of hypertext links being akin to faerie portals, taking the reader-traveller to a different reality. In the end I created about 20 motifs for The Knowing, enjoying the process of selecting a suitable motif to epitomize each key character. This chimed deeply with a central plot device I deploy (a series of heirlooms which allow my protagonist to connect vicariously to her ancestors). I also created a frontispiece and an ‘eye’ motif, based upon one of Kirk’s drawings. The latter also adorns the cover and sums up the insight and illumination of those with the ‘knowing’ of the title – Second Sight.

[image error]

Kirk’s eye of illumination, based upon an original in his 17th C. notebooks, by K. Manwaring 2017

So, with the book complete, I can add The Knowing to a list of my books I have illustrated: Spring Fall (1998); Green Fire (2004); The Bardic Handbook (2006); Oxfordshire Folk Tales (2012); Northamptonshire Folk Tales (2014) and Ballad Tales: an anthology of British ballads retold (2017), as well as a continuing series of literary walks for the Cotswold Life magazine. I hope my love affair with text and image will continue. Maybe one day I shall be able to collaborate with other artists and writers.

[image error]

Detail from the grave of Robert Kirk, by K. Manwaring 2017

Kevan Manwaring Copyright ©2017

April 10, 2017

Walking with Thomas

April 9, 2017

The Road Not Taken

[image error]

”Two roads diverged in a wood, And I – I took the one less travelled by…’ Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken, Photograph by Kevan Manwaring 2017

On the anniversary of the death of the poet Edward Thomas on Easter Monday, 9th April 1917, at the Battle of Arras, I wanted to share a screenplay I co-wrote with a fellow Dymock Poets enthusiast, Terence James back in 2010-2011, ‘Little Edens’ (or The Road Not Taken). It hasn’t been produced, but it has been performed in a script-in-hand read-thru the ‘Spaniel in the Works’ theatre company in Stroud. I share it memory of Edward Thomas and Robert Frost and the special friendship they enjoyed. I am an avid believer in creative community and in celebrating the ‘little edens’ of the everyday – the golden moments shared with friends, loved ones, animals, nature, and the spirit of place.

‘Little Edens’ – A Writer’s Statement

I want to develop this project because I am a poet and a lover of the British countryside, and this story celebrates both. I am interested in the period (Edwardian-Georgian-Twenties) having set my first novel, The Long Woman, in it (in its celebration of the English landscape and the Lost Generation, my book echoes some of the concerns of the screenplay). I am haunted by the artistic response in times of conflict – how can we ‘justify’ such rarefied activities as writing poetry in the face of conflict? – and I think the story of the Dymock Poets mirrors our own times and predicament, a hundred years on. Against the shadow of war, there is a brief, bright flowering of creativity in a small corner of the Gloucestershire countryside. This would be precious enough in its own right (one of the ‘little Edens’ of the film) but the fact that this convergence of poets and their muses produced some of the most memorable poetry in the English language shows that ‘something special’ occurred. Thomas might not have been able to ‘write a poem to save his life’, as he so poignantly said to his devoted friend, Eleanor Farjeon, but his poems have given him a kind of immortality – through them he lives on.

I am also fascinated by the influential friendship between the two poets, Robert Frost and Edward Thomas. When they first met, in October 1913, the former was yet to establish his literary reputation and the latter had yet to turn to poetry. Through their friendship, they inspired and encouraged each other. Thomas wrote favourable reviews of Frost’s early work, helping to launch his career, and Frost encouraged Thomas to try his hand at poetry, which he did from the end of 1914 – the year the film is set – up until his death in April 1917, in the battle of Arras. During this time he wrote the 150 poems that made his career. Frost returned to America with a burgeoning literary reputation – he went on to become a four-time Pulitzer Prize winning ‘grand old man of American poetry’. This trans-Atlantic friendship is the heart of the film – in microcosm, it mirrors the wider circle of the Dymock Poets and their wives. I find their fellowship heartening, especially in the face of war – and the community they share, the coterie at Dymock, a model for creative living. For a brief while they created and shared something golden.

The Dymock Poets (and the wider clique of the Georgian Poets, to whom they mostly

belonged) have fallen in and out of fashion over the years, but the astonishing convergence of talent (Frost, Thomas and the ‘Adonis’ of the Bloomsbury Set, Rupert Brooke) at such a poignant time deserves to be more widely-known. I picture ‘Little Edens’ as being a deeply beautiful and moving film – with many of the scenes filled with wide shots of lush English landscape; sleepy hamlets; faces a-glow around the hearth; evenings of poetry, cider and fellowship; the embryonic lines of classic poems; the colloquy of poets out on their rambles; contrasting with the harsher scenes of war and its consequences. Imagine elements of ‘Bright Star’; ‘Regeneration’; ‘A Month in the Country’; ‘Hedd Wyn’; and ‘The Edge of Love’.

A logline might be something like: ‘For one brief summer they found paradise — until the world found them.’

Kevan Manwaring Copyright © 27 August 2010

Here it is:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B65FARK-P4_HeXlYSmMwTEtHU0k/view?usp=sharing

Let me know what you think. Film producers and directors especially welcome!

April 6, 2017

A Wayfaring Stranger: Interview & Reading with Kevan Manwaring

[image error]

Listen to a 30 minute interview and reading with Rona Laycock, on The Writers’ Room, Corinium Radio, about my new novel, The Knowing – A Fantasy. Meet Sideways Brannelly, a trader between worlds, and hear about the research that went into the novel, my other books, my teaching, and up-and-coming events…

http://www.coriniumradio.co.uk/