Kevan Manwaring's Blog: The Bardic Academic, page 4

January 18, 2023

The Battle for the Trees

When we destroy nature, we destroy ourselves. The Battle of Verdun, France, 1916 took its toll on 300,000 lives and decimated the landscape. An unimaginable tragedy, but the impact of anthropogenic Climate Change, caused by rapacious Capitalism, scales the death-toll up to millions and results in mass extinctions.

Cad Goddeu (Battle for the Trees) is a proto-ecological poem featured in the 14th century Hans Taliesin (The Book of Taliesin). I have created my own poem based upon this. It was featured in a spoken word show, ‘Robin of the Wildwood’, which I co-created with Fire Springs and premiered in a woodland on May 1st. With priceless habitat being destroyed daily it seems more resonant than ever. We must all become defenders of the ‘wildwood’: biodiversity from the back garden to national parks to globally important wildernesses like Antarctica. In Britain the Right to Roam movement is a powerful modern iteration of this – especially in its evoking of folklore in the figures of Esme Boggart and Old Crockern. We need to defend our wild places.

Old Crockern is Rising by Nick Hayes, 2023 https://www.righttoroam.org.uk/

Performing in ‘Robin of the Wildwood’, Rocks East Woodland, near Bath

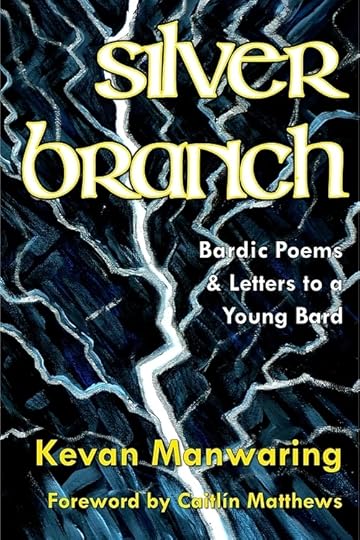

‘The Battle of the Trees’ is featured in Silver Branch: bardic poems (Awen, 2018). Signed copies available.

January 8, 2023

Time Takes a Cigarette 1

On David Bowie’s birthday another chance to read my 12-part flash fiction, inspired by his many guises.

Hogmanay. The Royal Mile is rammed to the ginnels. They’re wavering by the Waverley. Getting bolloxed by John Knox House. Friends. Loved ones. Strangers. Japanese students in fake ginger beards and Disney tartan. The countdown begins. Why do they only begin at ten? Some of us have been counting a lot longer. This. Moment. Has. Happened. Many. Times. Before. The crowd breathes in. The bells. Fireworks ejaculate across the city, brimstone spermatozoa impregnating the sky, if only sheer effort was enough. Thrombotic pensioners hold their shivering pets closer. Snogs spread like a zombie-plague through the crowd. Handshakes and manhugs. For a moment we’re all heroes. We’ve made it this far. Another number can be added to our parenthetical life-span. The daisy-chain of years. We link hands like DNA. It always seems to be the same faces. I swear I recognise half the people here, but I’m useless with names. Auld…

View original post 131 more words

January 5, 2023

His Box of Dark Materials (Part 3)

The third in our triptych of Children’s Fantasy with a dark wintry setting and/or tone is, chronologically, the link between Masefield’s series in the 30s, and Pullman’s in the late 90s. The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper was published in 1973 and is the second in a sequence that became known as the same. It is set in the Thames Valley and tilts it, via heavy snowfall, into an estranged, enchanted land, as The Box of Delights does with the Malvern Hills in Herefordshire. Like Masefield’s novel, it too features Herne the Hunter, and a young protagonist getting inveigled in a Manichaean fight between the forces of the Light and the Dark. Instead of a magical box, the young Will Stanton becomes The Sign Bearer, acquiring six ancient signs that help him in his battle against the Dark that assails his village and community (in His Dark Materials Lyra Belacqua becomes the ‘Sign Reader’ with the alethiometer – a device that enables the user to discover the truth). Will discovers the presence of The Old Ones in his neighbourhood – The Blacksmith, John ‘Wayland’ Smith; The Rider; The Hunter; The Lady, Mrs Thorncrofte; Merriman Lyon; and The Walker, aka Hawkin (who is like a shadow version of Cole Hawlings), among others – before it is revealed that he is the last of them, with a key role to play in the final battle. The river Thames is a dominating presence, and the land around it floods, as happens in La Belle Sauvage (the first in Pullman’s long-awaited follow-up to His Dark Materials, The Book of Dust). Cooper presents us with a vision of a flooded, rewilded England, echoing Richard Jefferies’ 1885 post-apocalyptic novel, After London: or Wild England. As with Alan Garner’s Alderley Edge, the landscape around Will’s village becomes a cross-hatch of the magical and the mundane. An old track becomes The Old Track, a fact which saves Will Stanton from The Rider. The magical maelstrom that erupts is navigated by knowledge of deep place, and by the bonds of community.

During the winter of 2021 the writer Robert Macfarlane instigated an online readalong on Twitter. The book had long been a favourite of his – reading it in childhood, he has then gone on to introduce it to his children, and to bring it the attention of a whole new generation of readers and listeners, for in the following year, he worked on an adaptation for the BBC World Service, produced by BBC Sounds/ Theatre Complicité, which was broadcast to synchronise with the Christmas setting of the novel (like The Box of Delights TV series). The twelve fifteen-minute episodes chimed well with the festive holiday, being released daily at breakfast time (GMT), cultivating a shared listening experience akin to when The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings radio adaptations were broadcast in the 70s, resulting in whole campuses practically grinding to a halt, as everyone listened in. The sound FX created by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop vividly brought to life the wintry, spectral ambience of the book – the supernatural ‘thickening’ that occurs as the apparent reality is destabilised by increasingly powerful intrusions – along with the resonant theme tune written and performed by Johnny Flynn. The Dark is Rising is intrusion fantasy at its best (to use Mendlesohn’s speculative taxonomy). Its effectiveness is thanks to a combination of a tangible setting, evocative seasonality, and the archetypal and the actual in the interweaving of the mythic, folkloric, and religious with the comforting familiarity of Christmas.

Each of these Fantasy series (in book and televisual format) – The Box of Delights; The Dark is Rising; and His Dark Materials – have all helped in restoring a sense of enchantment to the Yuletide season (with Pullman’s masterwork being only the most recent bauble to be added to the Tree of Story) reminding us of the spirit of Christmas, the wisdom of winter, and the importance of family during challenging times for all. And for that, we should be grateful to the writers, and to all who have brought their magic to life.

His Box of Dark Materials (Part 2)

The Box of Delights, or When the Wolves Were Running (1935) is a children’s fantasy novel by John Masefield (UK Poet Laureate 1930-1967). It is a sequel to The Midnight Folk (1927) which first introduces the young protagonist, Kay Harker, and features a coven, talking animals, and the formidable governess, Sylvia Daisy Pouncer, and the wizard Abner Brown – who reappear in the sequel, up to more nefarious deeds. The Box of Delights is set over a particularly snowy Christmas, with the English countryside transformed into a landscape of magical immanence. It was made into a very successful and much-loved BBC TV series, broadcast over Christmas 1984, featuring Patrick Troughton (the 2nd Doctor Who) as a centuries old cunning man, Cole Hawlings, Patricia Quinn as Sylvia Daisy Pouncer, Robert Stephens as Abner Brown, and Devin Stanfield as Kay Harker. The production, directed by Renny Rye and adapted by Alan Seymour, won several BAFTAs and RTS awards and featured special FX that were cutting-edge for their time (and, costing one million pounds, made it the most expensive children’s series produced on British television to date). The opening credits are deeply eerie – behind-the-sofa stuff, enhanced by the haunting, magical theme tune combining ‘The First Nowell’ with the third movement of the ‘Carol Symphony’.

The similarities of elements to His Dark Materials is remarkable. A young protagonist is embroiled in a supernatural mystery, which plunges them into an estranged, uncanny version of England; they are gifted a much sought after magical device, the titular Box of Delights, which affords the bearer magical powers (to shrink and to ‘go swift’); there is a sinister ‘Theological College’, where dark deeds are afoot; animals play a prominent part – a white horse that flies, wolves, stags – with characters turning into them (Herne the Hunter) or existing as unsettling hybrids (Pirate Rats); there is a flying car (foreshadowing the Intention Craft); adults are peculiar and distant, being either allies or enemies, with agency focused on the children; Sylvia Daisy Pouncer is an elegant, but ruthless femme fatale; and there is a rather spirited young girl, the tomboyish Jemima (a proto-Lyra figure). There is a steampunkish Brazen Head, and the summoning of demons. There is a brace of rather sinister vicars, and a backdrop of religiosity. The wintry landscape evokes the ambience of the Northern Lights. And when choristers are kidnapped by the malevolent monks they are ‘scrobbled’, rather like the Gobblers of Northern Lights – Mrs Coulter’s General Oblation Board, stealing children to gain access to the secret of dust.

It is as though Pullman took The Box of Delights as his source text, and rewrote it with the sensibilities of the late 20th Century – not to devalue his towering achievement. His Dark Materials is a worthy addition to a distinctly English strain of Fantasy, alongside Alice in Wonderland; Lud-in-the-Mist, The Lord of the Rings; The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, and Gormenghast. Pullman clearly drew upon many other influences too – not least John Milton’s Paradise Lost, but The Box of Delights preceded it by decades (1935; 1984), and is worth hunting down for any die-hard fans of His Dark Materials, or British winter-based Fantasy in general (of which there is a small, but distinct body of work). Its Special FX may not satisfy modern CGI-saturated audiences, although many work charmingly well within the context of a Children’s Fantasy, but there is true enchantment to be found here. The Box of Delights captures the magic of Christmas, as does our next Yuletide classic.

In the final part of this blog, I’ll discuss the other wintry classic that forms a stepping stone to His Dark Materials

January 4, 2023

His Box of Dark Materials (Part 1)

The BBC/HBO series, His Dark Materials, Season 3.

The long, dark nights of winter lend themselves to storytelling as friends and families gather around hearths (or plasma screens) – hypnotised by the flickering lights and the enchantment it conjures. The darkness is kept at bay by a re-affirmation of societal and familial bonds, special feasts, gift-giving, prayers, carols, games, and good cheer. And the Christmas tradition of storytelling – cultivated in Britain chiefly by Charles Dickens and MR James, but part of a wider oral tradition in the northern hemisphere of Yuletide tales. Close to the Arctic Circle, when the sun would barely rise above the horizon throughout the winter months, and the winter night seemed endless, storytelling was one of the sure-fired ways of maintaining community and mental health. Nowadays, with the virtual ubiquity of digital streaming platforms we turn more to TV dramas than skalds.

One of the most popular wintry tales of recent years began in 1995 with the publication of Northern Lights (The Golden Compass in North America and elsewhere), by British author, Philip Pullman. Winning the Carnegie Medal for children’s literature (and later the ‘Carnegie of Carnegies’ by public vote), this YA novel with huge cross-over appeal was to be the first of a trilogy that became known as His Dark Materials, which has been made into a successful TV series by Bad Wolf (the production company behind the regeneration of Doctor Who). Unlike the aborted movie franchise – of which, only the first book was adapted – Bad Wolf have completed the trilogy with the broadcast of the much-anticipated third and final season over Christmas, 2022. Delayed by the pandemic, the deferred gratification helped to sharpen the appetite of the fans, who had grown to love the characters, thanks to some inspired casting choices (multi-talented Hamilton-writer Lin-Manuel Miranda, in particular, as the aeronaut Lee Scoresby). Ruth Wilson (Mrs Coulter), James McAvoy (Lord Asriel), and newcomers Dafne Keen and Amir Wilson (as Lyra and Will) are pitch-perfect, and the whole thing is done with big-screen panache.

The novels stood out for not dumbing down for younger readers, but raising them up with intertextual allusions to William Blake and Milton’s Paradise Lost; and by drawing upon cutting-edge research into the ‘many worlds’ hypothesis of quantum mechanics – which has proven that, at a subatomic level, multiple states of existence (for tiny particles) are all possible at the same time. And, pioneering for its time, although more common now, Pullman’s novels did not shy away from difficult material (dysfunctional families; mental illness; murder; authoritarian governments). They were notable for the dark, edgy tone, and for fearlessly addressing shibboleths such as organised religion, the conception of a Creator-God, Original Sin, homosexuality and angels.

And yet, however ground-breaking the novels were (which, throughout their initial release, seemed far more mature, sophisticated, and better written than the incredibly popular Harry Potter novels) Pullman’s trilogy is not without precedent. Two previous children’s series paved the way, and their influence can be discernible.

In the next blog I will discuss the first of these…

Copyright (c) Kevan Manwaring 2023

January 3, 2023

Hawk Tongue

Goshawk in a Falconer’s Hand, Aubyn Trevor-Battye, 1903.

This poem was inspired by a tantalising fragment of folklore recorded by the metaphysical poet, Henry Vaughan. I had first read of it in Iain Sinclair’s psychogeographical evocation of the Welsh Borders, Landor’s Tower (Granta, 2001), which dramatized the moment Vaughan received his vision:

He kept paper, a pen, ink, close at hand. He would question the spirits. He lay with his eyes open, under the dark beams of the low ceiling, hearing cattle move restlessly in the fields, hearing the river, the small, common noises of that thick night — and he saw himself reach out for the pen. He transcribed this non-dream, the story one of the vanished dictated. About a man in a bed. Reaching for his quill. (2001)

The original account was recorded by Vaughan in a letter to his cousin, the antiquarian John Aubrey, in 1694 (only 2 years after the mysterious death of the Reverend Robert Kirk). In the letter, Vaughan discusses the Bards of Wales, and their inspiration (‘awen’, Welsh, f. noun, ‘inspiration’), before illustrating his brief account with this remarkable fragment:

I was told by a very sober, knowing person (now dead) that in his time, there was a young lad fatherless & motherless, soe very poor that he was forced to beg; butt att last was taken up by a rich man, that kept a great stock of sheep upon the mountains not far from the place where I now dwell who cloathed him & sent him into the mountains to keep his sheep. There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep in which he dreamt, that he saw a beautifull young man with a garland of green leafs upon his head, & an hawk upon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) att last lett the hawk fly att him, which (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Countrey, making songs upon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time.

The account was written in the ‘fading hours’ of the poet’s life, and was the last completed piece of writing of an illustrious career (Post, 2014: xv).

In all three instances – the original folk tale, Vaughan’s recording of it, and Sinclair’s retelling of it – inspiration and the creative act is captured. When I first read of the encounter, which seems to be another iteration of the trope of the divinely-inspired youth seen in tales of Lailoken, Merlin Ambrosius, and Taliesin in Scotland, Wales, and Ireland (Carey, 2020), I was inspired to write down an outline for a novel. The initial burst of enthusiasm passed, and the novel remains unwritten – but years later I was to recall the fragment during the run-up to the Soundpost 2019 ‘Fairy Gathering’ (see review in this issue). Having been depleted by the completion of my doctoral research project (discussed in ‘Performing Kirk’) I had not been able to write anything new for a few months. But when I visualised the handsome youth with the hawk upon his wrist, the awen started to flow, and I composed the poem above, which I first performed from memory at the Fairy Gathering on the final day. By capturing the moment of inspiration in verse, and performing it, I found inspiration started to flow once more.

Copyright (c) Kevan Manwaring, 2018

List of References

Carey, John, ‘In Search of Merlin’, Temenos Academy lecture, 27 May 2020. Available from: https://www.temenosacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/In-Search-of-Merlin-Prof-John-Carey-May-2020.pdf [accessed 6 June 2020]

Post, J. F., Henry Vaughan: The Unfolding Vision. Princeton University Press, 2014

Sinclair, Iain, Landor’s Tower, London: Granta, 2001

January 1, 2023

Bio*Wolf – Anglo-Saxon Cyberpunk

Cyber warrior by Clement Chee

Back in the Nineties I began performing as a storyteller and performance poet. In 1998 I won the Bardic Chair of Bath and became the Bard of Bath. I started to perform professionally. One of my first bookings was for a Samhain Celebration at the Peat Moors Visitor Centre on the Somerset Levels, where I performed the story of Beowulf in a roundhouse while a storm raged outside. I got to spend a night – alone – in that roundhouse, which didn’t even have a proper door – but snuggled up in my sleeping bag on the far side of the fire, I was toasty. The wind howled all night like a demon but didn’t tear the thatched roof off. In the morning I awoke to a flooded Somerset Levels, fallen trees, etc. But the roundhouse was intact. I like to think I had placated the storm crone – perhaps the lonely spirit of the fens, a mere-hag, like Grendel’s monstrous mother – with my tale.

Later that year, as the Millennium approached, I wrote a cyberpunk update of Beowulf, which I performed (from memory) at a show in a chapel in Bath with my storytelling friend, Kirsty Hartsiotis. And in the new year of 2000 I recorded it for my spoken word album, Global Warning, with added ambience from my friends Rae and Migo.

My version is inflected by all the Pre-Millennial-Tension that had been in the Zeitgeist over the previous year/decade/thirty years. As a member of Generation X I had grown up in anticipation of the Millennium — a word that first entered my consciousness when the Millennium Falcon blasted across our cinema screens in ’77. And now here it was. We sweated about that phantom virtual bogey, Y2K, and Britain celebrated with the ‘Millennium Dome’. We had a Labour government, and things could only get better.

So, grab your synthi-mead and gather in virtual Heorot as your cyber-scop sings of Bio*Wolf, the greatest warrior that was ever manufactured:

December 31, 2022

Hollow Lands – a Weird Tale by Kevan Manwaring

Hell Lane, Dorset, photographed by Kevan Manwaring

Graybarrow is a lonely bachelor obsessed with holloways, and trying to find the ‘glimmering girl’ he encountered in one when a young man…

My original story inspired by the famous Dorset holloway known as ‘Hell Lane’. Ambient sounds were recorded in situ. Additional sound FX and music was provided by Free Sound. Thank you to all who share their recordings there.

If you enjoy it, then like, share, and buy my a coffee:

ko-fi.com/kevanmanwaring

Photos from Hell Lane (credit: Kevan Manwaring, 2022)

December 30, 2022

The Child of Everything – an ecobardic warning

I wrote the lyrics for this song as a protest against GMO crops, which I performed at Trafalgar Square in front of 1000s of people at the Anti-GMO March in London. It was turned into this great track by my friends Rae McCready (main vocals; rhythm guitar) and Migo (lead guitar).

In the song I draw upon the anamorphic poetry of the Bardic Tradition – The Song of Amergin; Hans Taliesin – which I have performed for many years. In these poems the poet articulates a transpersonal, more-than-human consciousness, one that has been part of all things – the intricate, fragile web of life. The wisdom of the Bards foresaw what science was yet to discover: that we are part of nature and we exploit it at our peril.

December 28, 2022

Profoundly in Love with Pandora

James Cameron’s long-awaited Avatar sequel is an impressive eco-parable. Despite a forgettable plot, thin characters, and watery dialogue it still is a stunning spectacle that reminds you what cinema is for. It is totally immersive (excuse the pun) – watch it for the gorgeous visuals and deep ecology.

The mega-budget and the consumerist impact of the multiplex aside, one has to admire the environmentally-minded ethos of Cameron’s science fiction epic. The first film lured in massive crowds to make it the most successful film ever (at the time), with the promise of Cameron’s trademark crowd-pleasing blockbuster fodder – a formula he had refined since the 80s with a schlew of bighitters (The Terminator; T2: Aliens; The Abyss; Titanic). And yet, Avatar turned out to be loosely (and unofficially) based on Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, in its depiction of a paradisal planet’s exploitation and destruction by a rapacious, militiarised mankind. When the colossal Hometree was felled – the spiritual home of the Na’vi – we all felt it.

Apocalypse Now – the Na’vi rainforest burns. Still from Avatar: the Way of Water.

And with the sequel, and intended quintology (all presumably based upon the Chinese elements: wood, water, air, earth, fire), Cameron’s ecological agenda is being made explicit. Technically dazzling and pure cinema, but lacking the intellectual sophistication of say, Richard Power’s Pulitzer-Prize novel The Overstory (which I wish someone would adapt), Cameron’s magnum opus nevertheless uses a vast canvas to remind us of the inherent beauty and sanctity of nature — storytelling in a medium that will connect to the hearts and minds of millions. If it inspires even one person to action it will be worthwhile, but it has the potential to motivate a generation. If Cameron’s Avatar franchise could have the wide-reaching influence of Lucas’ Star Wars or the MCU – which are enjoyable but vacuous, then it could be a force for good in the world.

#AvatarTheWayOfWater reminded me of trekking in Borneo; and the solastalgia experienced there, the Amazon, etc. The heartbreaking fragility of these ecosystems I have tried to capture here: