Kevan Manwaring's Blog: The Bardic Academic, page 26

September 23, 2018

Honouring

The friends in our life are a true measure of success – the harvest of a life well-lived.

I am fortunate to know many talented people who I find inspiring and good company to boot. To be around them is a buzz, and their achievements mutually empowering. We raise each other up by stepping into our own power, by not being afraid to shine. I love seeing my friends do well. I praise their successes, cheer them on. Because I know something of their journey, of their struggles and sheer effort. When I am with them I feel more complete, because in some mysterious way they ‘hold’ something for me, an aspect of my own personality that they manifest in full. They are fully themselves, of course, but something in them draws me to them. I sense a kindred spirit. We share common ground – interests, experiences, obsessions, ambitions, sense of humour, wounds, or beliefs. They may just make me smile, make me feel alive, or make me feel more like me. I can be myself around them. The conversation flows. I feel listened to, received, and reciprocated. Seen. Heard. Held. They catch me when I fall, and without a second’s thought I do the same for them. I feel ‘greater than’, instead of ‘less than’, in their presence – not diminished or undermined, but raised up – not in an egotistical sense, but in an ennobled one. In such company I feel somehow things fall into place: a little piece of the universe’s puzzle slots home.

And so I wish to honour these friendships that I feel so honoured by. There are many ways of doing this – by baking a cake, singing a song, writing a letter, handcrafting something, or simply spending quality time with them. Last month I celebrated my 49th birthday in Stroud with ‘A Night of Bards’ – a gathering of storytellers, poets and singers to ‘wet the baby’s head’ of my new book, Silver Branch: bardic poems (published by Awen Publications), launched on that date. It was a special evening, brief but heart-warming and flowing with awen and camaraderie. I took photos, as did my friends, and I’ve used some of these to recreate some of the performances in what I call ‘bardic portraits’, intended to capture not an exact likeness but the energy of the performer, their presence. I incorporate a key phrase from their contribution, and have slowly worked my way through the dozen or so performers over the last month. It has been a nice way to remember the evening, enjoying it again like a fine feast, but in particular, a chance to focus in on each bard’s unique quality and talent. To bring awareness to these remarkable friends and the skein of friendships that we share.

Other friends who weren’t present on the evening but who have performed at other events I’ve organised over the years I may get around to also. They all deserve to be celebrated. Collectively they represent an inspiring microcosm of contemporary bardism. Who knows, maybe my sketches may provide a record for posterity; but more importantly they are intended to honour the subjects while they are here – to give thanks for their being vibrantly alive at this time and place in human history, and for touching my life.

Kevan Manwaring, 23 September 2018

Bardic Portraits from ‘A Night of Bards’ (Stroud, 19 Aug. 2018) by Kevan Manwaring

August 31, 2018

Sketchtember

Janey’s airstream by Kevan Manwaring (Medium: water-soluble pencil) 2017

The artist Paul Klee once wrote that “Drawing is taking a line for a walk”. Well, how about talking a line for a month-long walk, by rising to the challenge of Sketchtember (AKA ‘Septpencil’) and attempting a pencil sketch every day throughout the month of September? Sketches can literally five minute doodles or two hour masterpieces, in graphic or coloured, on any subject you fancy – the main thing is to have fun!

The idea came to me while undertaking Jake Parker’s great initiative ‘Inktober’ last year. I enjoyed the challenge of doing an ink sketch a day for a month immensely, and really noticed how my drawings improved over four weeks. I thought a natural predecessor would be a month of pencil sketching (I love the sensitivity of pencil and I’m huge fan of masters like Burne Jones and Alan Lee) and Sketchtember was born!

As a schoolkid drawing was my superpower, the art room my ‘Fortress of Solitude’ – well, not quite, as I’d often hang out there with fellow scribblers, away from the rough-and-tumble of the playground, the dark sarcasm of the common room. I flourished at art – it was great to have a subject I was good at, but more importantly, I sketched at home for enjoyment. I drew everyday; it was as natural as breathing. I made up comic strips with friends, and used my illustrations for the world-building of roleplaying games. It was perhaps inevitable that I ended up at art college, but although I got a great deal from the creativity bootcamp of my Foundation degree, three years of Fine Art was like aversion therapy. It made me too self-aware, as an artist, to the point of paralysis, and made me realise how pretentious and vacuous the art world can be (back then the cult of the personality that was Brit Art was very much in vogue – and the art of the sacred that I was into very much wasn’t). Instead, I turned to community arts and, apart from the odd poster, left my sketching behind. One by-product of my degree was writing – the dissertation taught me something of the discipline, but it was during a gap year that I started to write poetry. Poetry is an act of perception, a way of seeing the world, and I soon realised my art-training enriched my writing, and vice versa. Use of imagery, symbolism, detail, and close observation of the human animal – all of this fed into my poems and stories. And when I started to create pamphlets, and then eventually found and run a small press, the art and design skills really came into their own. They hadn’t gone away. But perhaps I had lost some of the joy. I no longer sketched for fun.

Over the last couple of years, during the intensive process of working on a PhD I have rediscovered the joy of sketching (cue 1970s manual with interesting poses…). After a day on the computer, working exhaustively with words, it is very soothing to just push colour around on a page … shapes, tones, shading. I found it actually enhanced my mental health – one becomes absorbed for an hour or two and all the voices, all the white noise of the day, fades away. It is no coincidence that the colouring-in books have become massively popular in recent years (although creating your own sketch is very different from just colouring in someone else’s). So, for that reason alone – for the ‘well-being’ factor, I recommend having a go. See it not as another task on the ‘to do’ list, but a bit of self-care. Don’t do it for anyone else, to compete or compare – do it for yourself, because it’ll make you feel relaxed, even good about yourself.

The blank page is a gift of freedom – a doorway for your imagination. It invites you to step through.

All you have to do is post your sketch, however embryonic, each day on Twitter, using the hashtag #SKETCHTEMBER Encourage friends to join in, even those who say they ‘can’t draw’ (everyone can make a mark – we’ve been doing it since the dawn of humankind). Follow other sketchers – support one another. And feel free to share inspiring pencil art to motivate and inspire. There must be a world of great pencil art out there. The classics of Western Art are to be admired and studied, but outsider art, and art from other traditions and cultures is waiting to be appreciated too.

Of course, racist, sexist or offensive sketches are not welcome in Sketchtember, but you know better. Let’s celebrate our creativity and use Twitter for something other than the Trumposphere!

I’ve decided not to create a list of prompts this time – I’m going for (mainly) portraits and animals this time. If you need some ideas, then look for ‘the 30 day drawing challenge’.

Let me know how you get on. Remember to use the hashtag. Happy Sketching!

Kevan Manwaring

31 August 2018

If you need tips and techniques the best place to start is with Betty Edward’s classic Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain: A Course in Enhancing Creativity and Artistic Confidence. There are many other books, websites, youtubes clips, etc, out there, but this one worked for me when I did my Foundation in Art and Design back in the late eighties!

A month of sketching not enough? Keep going, in ink with Inktober! Jake Parker’s site: https://www.mrjakeparker.com/inktober-1/

August 21, 2018

My Funeral

[image error]

It is a pleasant sensation, lying back in the wicker coffin decorated with ribbons and notes, feeling my work here on Earth is (hopefully) done and I can finally rest. The sounds of the funeral celebration swim around me – subdued conversation, subtle harp music – and I’m too intrigued too lie there for long, so I get up and have a look around, which involves me pushing up and floating through the lid of the casket, and above the gathered. It feels a bit weird, but in truth I’m a lot lighter than I normally am, due to donating any organs that could be of use to any who need them. Laughing, I realise I’m a holey ghost, for a brief while at least, but I’m useless at spooking people. It’s just too nice a day, and I don’t want to spoil it by given anyone the collywobbles. I am relieved to see it is a green funeral celebration, being held outside – somewhere beautiful in the West Country. I think I have been here before. It is a lovely site, in view of the hills I love so much, and their ancient monuments. It is a fresh, sunny day – even if there is cloud, the sun keeps breaking through, blessing the land with light, the heads of the mourners: friends, family, loved ones. I am delighted to see no one is wearing black, but a rainbow of colours, with many wearing the green and blue I requested: green to symbolise my love of the Earth, and blue for the Bardic Tradition I honoured and endeavoured to update and promote – my life’s work. It is so good to see so many beloved faces here – people dear to me from far and wide. I am deeply touched. To the strains of ‘Made to Love Magic’ by Nick Drake, the coffin is placed in the centre of the gathering, and, facilitated very graciously by a pagan celebrant – no Christian platitudes here. Spontaneously, folk stand up to share their heartfelt sentiments, memories, poems, even songs. There are sweet tears of fondness, the laughter of recognition. People who hardly known one another support each other in their grief. They are allowed to grieve in any way they wish, even if it is to show no ‘feelings’ at all. For some grief is a very private thing. Others like to externalise it, let it be witnessed – in lamentation, in weeping, in agonised moans, in dance, in stillness, in rage, in vulnerability. All is welcome here. Instead of flowers there is a collection for Tree Aid. The celebrant – could that be one of my wise friends? – leads the gatherers through the final stages. Then, as ‘Can’t Find My Way Home’ is played (the Swans’ version), the casket is conveyed to the grave where half a dozen of my closest friends lower me gently into the earth. Everyone takes turns to cast in some soil and say a few final words, in private to me. Once the grave is filled in, an oak sapling is planted on top of me, blessed with spring water from Glastonbury (red and white), Hawkwood College, and St John the Baptist’s, Boughton Green, Northampton. Forming a circle, everyone holds hands, chanting the awen three times. A plaque is attached, which simply reads: ‘Kevan Manwaring, Bard’ followed by the parentheses of my dates. And that’s that. As they depart the field of peace, the gathered pay their respects, consoling those closest to me: my partner, my family. Then, in little groups, the mourners drive away to the bardic wake, where fine food and drink await to ground everyone. Hitching a lift, I follow, but I am fading – a phantom hitchhiker. At the wake, riotously decorated with images of my life, the meadhorn is passed around and toasts are made. It is a chance to talk and share, followed by impromptu performances by my talented, bardic friends, who turn it into a bit of a session – there’s even with dancing, for what better way to celebrate a life, than with life? My books are donated, as a collection, to start a bardic library, to inspire future generations. My artwork, unusual items of clothing, and object d’art are displayed and folk help themselves to whatever speaks to them – something to remember me by. I am going … but a few details niggle me, so I whisper them to a keen-eared couple of pals, who nearly drops their drinks. Any money or continuing royalties from my ‘literary estate’, if I have any, is used to start a ‘New Awe fund’, managed by Awen Publications, to publish previously unpublished writers of any age or background willing to engage with ecobardic or goldendark principles. My papers (manuscripts, notebooks, files and folders), if there is any interest, are given to the Gloucestershire archives, or just burned in a glorious, drunken bonfire. If folk wish to remember my life then an annual, informal bardic gathering at Delapré Abbey on my birthday is my final wish – nothing grandiose, just friends and family sharing a picnic in the sun-dappled oak grove in the heart of Delapré, where it all began for me. The party continues, but I slip away. I was never good at goodbyes – until now. My soul sighs with relief as I pass on, content, deeply touched that my friends and family have honoured my wishes and given me the send off I have always wanted.

Kevan Manwaring, 20 August 2018

August 3, 2018

Fool for a Fisher King

SILBURY: the miraculous balance – Peter Please & friends

[image error]

This beautifully-made companion piece to Peter Please’s album of the early 80s, Uffington, Silbury: the miraculous balance, released on a limited edition vinyl, completes a remarkable long-term project of deep mapping that was instigated by The Chronicles of the White Horse (1982), and extended in a singular direction by his love letter to a Wiltshire water meadow, Clattinger: an alphabet of signs from nature (2008) – unique artefacts that between them triangulate a numinous corner of the county (Uffington; Clattinger; Silbury), one replete in ancient monuments, biodiversity and a mulch of social history.

Silbury draws upon a pair of Peter’s previous works (Clattinger, and Spoken Idylls: everyday illuminations) cherry-picking key extracts and giving them new voices and sometimes musical settings. It is a fecund work of creative collaboration. Included in this bardic ark are the talents of Paul Darby (The Yirdbards), The Bookshop Band (Beth Porter and Ben Please), Richard Secombe, plus the Silbury Pop-Up Choir conducted and arranged by Masha Kastner; not forgetting the gorgeous cover art by Caroline Waterlow.

The seasonal quarter of ‘The Swillbrook Song: spring/summer/autumn/winter’, provides a loose circadian framing narrative. Instrumental pieces interweave with spoken word and songs, choral pieces, chants and ‘raps’. It is an eclectic mix – like a traditionally-managed hay meadow strewn with rare species. There is a whimsical, fey, sometimes elegiac quality that evokes the ambience of an ‘Incredible String Band’ album. It has been released in 2018 but could have been released in 1968 – a time-capsule of re-enchantment for our modern wasteland, a fool for a fisher king, an old goblet found in a field that turns out to be the Holy Grail (possibly).

Peter describes the ‘miraculous balance’ of the album (‘Between time and eternity, earth and heaven…’ as: ‘a still point to view our relationship with a bewildering complex world.’ It offers a counter-spell to our disembodied, virtual lives, grounded as it is in place and community. In its quiet, undemonstrative way it offers a way through: ‘by making the land a sacred part of [your] community.’ By knowing the land we come to know ourselves, and each has a place in the circle. Silbury hill, mysterious chalk mound, raised by many hands 4,500 years ago, is a testimony to this kind of mutual effort and wish to connect with something greater than ourselves, and Silbury, the album, does so to, in its singular way, rising against the chilly zeitgeist, an audial and ageless ‘Winterbourne’.

Kevan Manwaring, 3 August 2018

Silbury: the miraculous balance is available from Away Publications http://www.peteralfredplease.co.uk

August 2, 2018

Songwalker

Going for a song. Hadrian’s Wall, K. Manwaring July 2018

SINGING THE WAY

Recently I walked the Pennine Way national trail – a 253* mile footpath that runs from Edale Derbyshire to Kirk Yetholm in the Scottish Borders. It follows, roughly, the spine of England – the Pennine Hills – into the Cheviots, and crosses three national parks: the Peak District, the Yorkshire Moors, and the Northumberland national park, as well as the North Pennine Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. I walked it solo (except for a couple of days when a dear friend joined me) over 18 days, with a couple of half-day rest-stops in Haworth and on Hadrian’s Wall. I wasn’t attempting to break any records or myself – it was my summer vacation ‘wind-down’, a detox from all things digital and academic, and I wanted to allow myself time to stand and stare, or sit and sketch, wild swim or wander lonely as a cloud, as the mood took me. To keep myself going over wild stretches of moorland, dusty tracks, or hot hillsides, I sang. This is the fourth long-distance path in which I’ve found singing has really helped me to ‘keep on keeping on’ – putting one foot in front of the other for mile after mile, hour after hour, day after day, and, more, it really enriches the experience. Each day I chose a song – either learning it on the hoof, or drawing it from my repertoire. If it was a new song, I would sing each verse until I had committed it to memory, then moved on to the next, and so on, until ‘the form [had] patterned in my head’ (as the memorable poem, ‘Real Property’ by Harold Monro goes). Then I would sing it over a few times, finding my way into the song, finding the right voice for it. Often the song’s content, its mood, its message, would chime with the morning, with the landscape I was moving through, in synchronous and profound ways. It sometimes felt like a way of ‘giving thanks’ for the day, for reciprocating what I was experiencing – a praise song and a focalisation of my phenomenological interface with place and its ontological layers, or, to put it more simply: grooving on the genius loci.

Here are the songs I sang, in order (they represent the main ‘song of the day’ although others came and went organically). I selected songs that were thematically-apt or simply ‘jaunty’, amusing and morale-lifting.

Day 1, Edale to Torside: Mist-covered Mountains adapted from the Gaelic by Malcolm MacFarlane, version by Chantelle Smith.

Day 2, Torside to Standedge: Ramblin’ Man by Hank Williams.

Day 3, Standedge to Mankinholes: John Ball by Sydney Carter.

Day 4, Mankinholes to Haworth: The Skye Boat Song by Sir Harold Boulton.

Day 5, Haworth to Ickornshaw: The Boatman by The Levellers.

Day 6, Ickornshaw to Malham: Above (plus ‘Pendle Song’ shared by Anthony Nanson).

Day 7, Malham to Horton-in-Ribblesdale: The Manchester Rambler by Ewan MacColl (plus ‘Scout Song’ by Anthony Nanson).

Day 8, Horton to Hawes: Green Grow the Rushes by Robert Burns.

Day 9: Hawes to Keld: Crooked Jack by Dominic Behan.

Day 10, Keld to Baldersdale: Blowin’ in the Wind by Bob Dylan.

Day 11, Baldersdale to Langdon Beck: A Place called England by Maggie Holland.

Day 12, Langdon Beck to Dufton: Wayfaring Stranger (Norma Waterson version)

Day 13, Dufton to Alston: Pilgrim on the Pennine Way by Pete Coe.

Day 14, Alston to Greenhead: This Land is Our Land by Woody Guthrie.

Day 15, Greenhead to The Sill: King of the Road by Roger Miller.

Day 16, The Sill to Bellingham: Carrick Fergus (Marko Gallaidhe version)

Day 17, Bellingham to Byrness: Man of Constant Sorrow (based upon a song by Dick Burnett) John Allen / Victor Carrera / Scott Mills.

Day 18, Byrness to Kirk Yetholm: Caledonia by Dougie Maclean; Both Sides o’ Tweed by Dick Gaughan.

I would highly recommend this way of experiencing the landscape**. To start the day with a song in your heart lends wings to your feet. It is also is very liberating for the voice. In the middle of nature you can sing your heart out, without fear of criticism or ridicule. It hyper-sensitised my hearing whenever I fell silent (which was often for long stretches of time). And time and time again I found it created interesting encounters with animals. Song changes our relationship to nature – it plugs us into the grid of Creation. Many traditions talk of ‘divine utterance’ and the way the world was sung into being. In some small way, by songwalking, one feels part of this choir – both singing praise to the world and singing the world into being as each step reveals new wonders to our reawakened senses.

Copyright © Kevan Manwaring 2 August 2018

[image error]

Cairn above Byrness, dawn of final day. Only 26 miles to go: songs don’t fail me now! K. Manwaring, July 2018

*The route can vary between 253 and 268 miles depending on optional routes, and distances of accommodation at the end of each day!

**If you are interested in songwalking get in touch. I would be fascinated to hear of your experiences, and would love to share a walk with you. Wayfarers of all abilities (poets, storytellers, artists, musicians, sound artists, etc) welcome!

July 31, 2018

Missionary Impossible

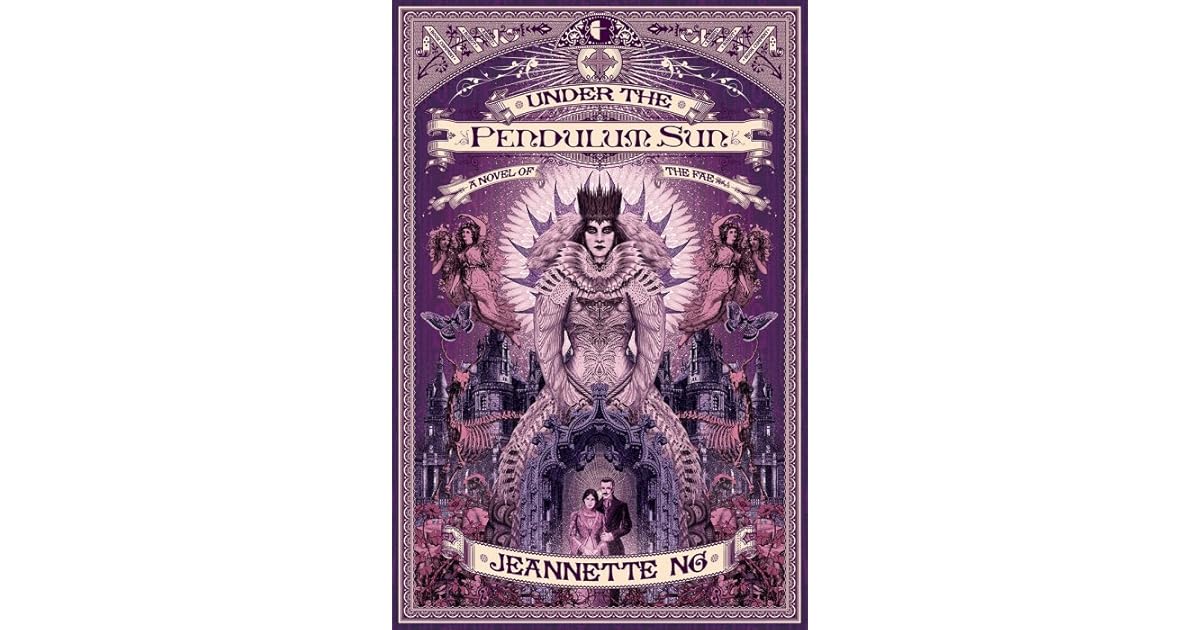

Under the Pendulum Sun by Jeannette Ng – a review

There is much to commend in Ng’s ‘novel of the Fae’ about troubled sibling missionaries, Catherine and Laon Helstone, and their strange adventures in Elphane/Arcadia. Ng manages to evoke through her finely-wrought prose the claustrophobic atmosphere of a dense Victorian novel of morality and misadventure; and also the alien, quixotic climate of Faerie. By making her brother and sister protagonists missionaries seeking out to bring the Word of the Lord to the benighted ‘souls’ of this recently revealed Otherworld the novel both aligns with and subverts the colonial project – for the ‘too close’ missionaries are far from without sin, and their mission is futile at worst, at best a metaphysical challenge (do the Fae have souls? what is their place in God’s creation?). Access to the ‘inner lands’ for further proselytising is the main plot McGuffin, but the chief line of desire revolves around Catherine’s unhealthy obsession with her brother – who is a Branwell/Heathcliff/Rochester type. Dark, moody and (to some) irresistible. This is not surprising as Ng clearly riffs upon the Brontë family dynamic and legendarium (which the famous siblings of Haworth created in their younger years). Here, this juvenilia is given the full-bloodied treatment, as Ng feeds it into the mulch of her world-building. The mise-en-scène of each chapter is vividly imagined, but often this seems to be at the expense of narrative traction. Sometimes it is hard to know exactly what is happening – many of the scenes have the feverish intensity and illogic of a dream. And although the minutiae of Elphane, in particular life in Gethsemane, the Pale Queen’s castle, is exquisitely imagined, the broader brushstrokes of this Secondary World are less convincing: the pendulum sun of the title, the fish of the moon swimming in the sky, and sea whales (which seem to be both made of rickety whicker, yet contain a microcosmic ocean). This no doubt is intended to deliberately subvert the verisimilitude and make the otherworldly realm lack naturalism – and such bold imagery may be original and memorable, it threatens to make the whole edifice a leaky vessel, which I could not fully buy into (rather like CS Lewis’ car-boot Narnia). Another problem for me was reader-identification. Like a lot of modern fiction I find a lack of relatability – I cannot connect with the main characters, finding it difficult to emotionally invest in them. And narrative traction is missing (for me). I turned the pages out of professional curiosity, not out of urgency. Yet unlike a lot of (modern) fantasy, Ng’s prose aspires to a slightly elevated register, which successfully evokes the music of strangeness (‘a catch of the breath’, as Susan Cooper describes it). Ng’s depiction of Faerie is the best I have seen in contemporary fantasy. She lards each chapter with an epigraph, pastiches written wittily in the style of bombastic Victoriana, or stuffy exegeses. These often evoke the texture of an AS Byatt novel (notably Possession) but are convincingly done. Ng’s academic background and interests (MA in Medieval and Renaissance Studies/medieval and missionary theology) clearly inform these, but I found them rather laborious after a while (one can always choose whether to read them or not). Perhaps too much salt, and not enough meat for my taste. Nevertheless, Ng’s first novel bodes well. She is evidently a talented writer with a vivid, and original imagination. I look forward to seeing what she conjures up next.

Kevan Manwaring 31 July 2018

June 22, 2018

Solstice Sunset

[image error]

Enter a caption

Resisting night’s gravity

I rise to the Heavens,

clay on boots,

dusk at my heels,

slipping up to the

lonely grove on the brow,

where a year ago,

we planted a circle of hope.

Now I stand alone

in silent vigil.

Aurora of the day

sliding away, behind

Rodborough’s bear shoulders.

It is a satisfying death –

a great actor’s swansong.

A star born for this moment.

The lights fade, and, on cue,

another nova.

No desecrating ruckus

at a stone circle is needed

to mark this annual valediction – leave

the vandals to their

trilithon abuse and stoned selfies.

I have no need of the Am-dram

of dodgy rituals,

the posturing of ill-cast hierophants.

My gaze is for the sun alone.

Quietly, I say goodbye.

From The Immanent Moment, Awen 2010

June 21, 2018

Creative Resistance

[image error]

Be more than a Selfie. Revellers awaiting the summer solstice sunrise at Stonehenge, 21 June 2018. K. Manwaring

In these challenging times it is easy to lose hope, to feel powerless against the dark forces active in the world – racism, sexism, child imprisonment, jingoism, xenophobia, animal cruelty, destruction of the environment, and institutionalised inequality.

But we are many, and they are few. Our time to step up is now. History is our witness.

Creative Resistance encourages

Acts of solidarity

Community

Resilience

Art

Writing

Music

Dance

Fashion

Film

Comix

New media

It’s easy as 1, 2, 3 …

Create – paint, draw, dance, sculpt, write, cook, tailor, garden, code…

Connect – face-to-face, online, cafes, conferences, pubs, symposia, festivals, parks

Communicate – by any means necessary, get your work and your message out there.

Organise Creative Resistance:

Meet ups (face-to-face); Sharings (online); Happenings; Publications (print/digital); Recordings; Exhibitions…

The effectiveness of such a movement will be in a grassroots, non-hierarchical approach. Organise your own gatherings, create your own messages of resistance. A wikimanifesto is better than one person or a small group defining things. All can add their voice.

It is important to fight Fascism (let us call it by its name) on all levels. Let us fight using our skills, our talents, in ways which are empowering and nurturing. If you are a political campaigner, let that be your poetry. If you prefer direct action, then make that your art. But those of us who are creative may prefer to use our abilities to resist, critique, and create positive alternatives.

Be a local Creative Resistance organiser. Bring folk together. Start the conversation, get creating, and get organised, while we still have the liberty to do so. Fight for your Human Rights before they are taken away. Defend the vulnerable. Do not be a passive witness. Defy and challenge with glorious acts of creativity celebrating the diversity of humanity.

Kevan Manwaring 20 June 2018

June 17, 2018

Swimming in the River of Time

News from Nowhere, or An Epoch of Rest, Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance (1890) by William Morris

[image error]

Kelmscott Manor, the beautiful home of William Morris. K. Manwaring, 2018

News from Nowhere is an iconic ‘fantasy’ novel from the Arts and Crafts visionary and polymath William Morris. Although it is an important work for its lucid dramatisation of Morris’ Socialist ideals, on the surface it appears to be a work of the Fantastic (a timeslip narrative with a loose science fictional device): a man called William ‘Guest’ (a thinly-veiled alter ego of the author) goes for a swim in the river Thames in the late 19th Century and emerges in the early 21st Century, to see a vision of England transformed into a place of restored beauty, craftsmanship, and co-operation. Guest explores this land, with the Thames providing the common link, as he slowly wends his way upriver. The novel’s extent is demarcate by two of his homes: in Hammersmith and Kelmscott, and focuses on a stretch of the river that Morris knew well. In this sense the novel is geographically unambitious, but in many other ways, it was thinking big – certainly beyond the consensus reality of his day. Morris reimagines reality according to his principles, providing a blueprint to aspire to, for some at least.

Morris’ utopia is vividly imagined and alluring on the surface, as pleasant to dip into a wild swim in a glittering river on a summer’s day: an aesthetic and harmonious Arts and Crafts utopia, with an emphasis on ‘work for pleasure’, common ownership, co-operation, and liberty to choose where one lives, one’s profession, and one’s morality. The self-governing anarchists live in beautiful houses, wear beautiful clothes, and make beautiful things. It is perhaps all too good to be true, and in most fictional utopias this is when the protagonist discovers the ugly truth, the mask slips, and they find themselves trapped in some nightmare.

Well, for some, Morris’ utopia undoubtedly would be. It is perhaps a bit like living in a Tolkienesque Shire – a bucolic aesthetic that belies some worrying subtexts. For a start, it is completely Anglocentric – Morris depicts a very English utopia: what has happened to the rest of the world is not discussed, except for a brief, disparaging reference to America being reduced to a ‘wasteland’. There is a worrying emphasis on women being pretty – every female Guest meets is assessed in this way. The novel is clearly written from a male gaze. There is nothing ‘wrong’ about appreciating female beauty – but when it becomes the chief characteristic, the defining trait, that is problematic; in addition, the women are on the whole portrayed as being content in domestic roles, or being a bit empty-headed (except for the stonemason and the free-spirited Ellen, who is inquisitive and seems to know more than she lets on – a portrait of Jane Morris, similarly ‘snatched’ from the working classes; in the way Guest is clearly Morris himself?). Also, New from Nowhere is very white, cis-gendered, and straight, but Morris was writing from his time (late 19th C) even though he was imagining the early 21st Century. His imagine didn’t stretch far enough to imagine alterity. His vision seems impossibly idealistic, and relies upon the common decency and common sense of the masses – everyone being nice and abiding by agreed values – which, as we can see at the moment, is very unlikely, even when laws are enforced…There is the odd crime of passion, but these are forgiven by society as the perpetrator is left to come to terms with their actions. Yet human nature doesn’t tend to be that enlightened. Even if one society achieves this level, there will always be other groups wishing either to seize its resources or simply destroy it (as Aldous Huxley imagines in his heartbreaking utopia, Island).

Yet, Morris’s ‘utopian romance’ is a hopeful act of positive visualisation – a thought experiment for the world the Socialist Morris wish to see manifest. For him it was a vision much-longed for; and one he tried to implement with his restless energy and huge output. He perhaps achieved in at Kelmscott and the other centres of Arts and Crafts activity.

Now there is an appreciation of artisan skills, of the hand-made, the hand-crafted, the home-grown – farmers markets and craft markets are very popular; and Transition Town schemes are skilling people up for the ‘power down’… Alternative currencies such as LETS and Timeshare have been trialled, but the lack of money seems the least convincing of Morris’ notions – though with the devastation caused by Neoliberalism, perhaps the one that needs addressing as urgently as the environmental one. We need the replace the false economy of venture capitalism, of ‘progress’ and ‘growth’ (based upon finite, dwindling resources and catastrophically damaged biosphere) with the more sustainable one of Deep Ecology.

Morris’ vision is a message in a bottle cast in time’s stream, and although it has many alluring qualities, perhaps it is not radical enough, as it clings to some medieval paradise that never was, yet these thought experiments are worth undertaking. Morris throws down the gauntlet for us all to imagine the world we would like to live in.

[image error]

The river Thames begins near Kemble, K. Manwaring 2018

Kevan Manwaring 17 June 2018

June 4, 2018

The Pattern of Friendship

d

[image error]

Two Women in a Garden, Eric Ravilious, 1933

Eric Ravilious was a multi-talented English painter, designer, illustrator, muralist and wood engraver whose tragically brief parenthetical dates (1903-1942) contain an extraordinary career and life that touched many lives, in particular the remarkable nebula of talent that coalesced around the Royal College of Art classes of the early Twenties: Edward Bawden, Barnett Freedman, Thomas Hennell, Douglas Percy Bliss, and John and Paul Nash. The women were equally talented – Helen Binyon, Peggy Angus, Edna Marx and Diana Low. Elaine ‘Tirza’ Garwood, who went on to marry Ravilious, excelled at depictions of everyday lives: well-observed vignettes of social history that were witty, and ironically aware of the fault-lines of society.

Inspired by William Rothenstein – a ‘father’ figure to this unofficial movement, who encouraged his pupils to explore different forms, to be catholic in their approach; and the presence of Paul Nash – one of most important artists of the 20th Century, who, though he only taught two terms at the RCA, had a huge influence on his cohort. Nash, like Rothenstein, practiced not a ‘top down’ kind of teaching, but one that flattened the usual hierarchies, with teacher and students getting stuck in together and learning as they went, through practice. Nash greatly encouraged his protégés, and was instrumental in setting up opportunities for them, artistic commissions and contracts in the real world (Ministry of Transport; the BBC; book publishers; Wedgwood; Ministry of War), deconstructing the elitism of a Fine Art disengaged from society. Book design and illustration, fabrics, wallpaper, public notices, murals, pottery, posters and prints – nothing was beyond their remit or abilities.

[image error]

The Long Man of Wilmington, Eric Ravilious, 1939

Through the painstaking research of Andy Friend, curator of the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne and author of Ravilious & Co.: The Pattern of Friendship (Thames and Hudson, 2017), we now know how this loosely affiliated band of artists and designers inspired and supported one another. Friend was instrumental in creating this major exhibition, which opened at his gallery last year, and has toured Sheffield and now Compton Verney.

White Horse of Uffington, Eric Ravilious, 1939

Ravilious, whose art, after long decades of (relative) obscurity, has experienced a huge surge of appreciation, is rightly the star of the show. His work, appearing with increasing frequency in magazines, newspapers, websites, postcards and prints, is rapidly becoming iconic. His apparently ‘austere’ or understated style chimes with the zeitgeist (one that is finding a consoling fiction in the ‘keep calm and carry on’ vintage aesthetic of WW2). It could be accused of the same (strangely) cosy nostalgia, and of being all surface and no substance – but there is something more going on in his work, which makes its effect linger. The South Downs, which Ravilious made his own (after a productive year at a much-loved ‘Furlongs’), are depicted in soothingly muted tones and a series of pulsing lines, suggesting movement, a frozen wave, electrifying the ostensibly still, empty scene with a charge of nascent energy – as though the slumbering giant of Albion was about to awaken. The foreground is often focalised by a piece of machinery – a watermill creaks in the wind, a steam train passes a white horse chalk figure, a plough breaks the undulating downland with its perpendicularity, a gypsy caravan contrasts the stark silhouette of winter trees. There is a tinge of melancholy, perhaps, in the often muted light, but there is also something infinitely soothing in the quietude they depict. And the light is always there, in the breaks in the line and thinning washes of colour – as though just below the surface, about to irupt through at any moment. Immanence and evanescence are intrinsic qualities in the work of Ravilious – no surprise then his favourite times to paint were sunrise and twilight. He spent his life trying to capture this fleeting light, a moth to the flame.

Tiger Moth, Eric Ravilious, 1942

Seeing the artists and designers side-by-side makes for some interesting comparisons. Paul Nash is the major figure, whose ‘daemonic urge’ outshines his brother’s, John, but in one painting (the interior of a wood) John outdoes his brother; Ravilious is the star of the show, but occasionally he is outclassed in single works by his peers, Bawden (in painting – e.g. ‘Nocturnes’), Freedman (in his submarine lithographs), Tirza (in her exquisitely observed and rendered engraving), but none of it is competitive. There is just a healthy cross-fertilisation. The lesser occasionally outshines the greater, and collectively they created an extra-ordinary outpouring of work, as Enid Marx reflected in 1989: ‘I have no illusions when it comes to my own standing, it’s all a matter of a number of individuals forming a collective school. In the arts this has always been so … the lesser pebbles become sand.’

Eric Ravilious became a war artist – and his palette darkened (as can be seen in a quartet of dramatic paintings executed for the Admiralty). He was in familiar territory depicting the industrial and mechanised in the landscape for the Army, but he had a yearning to experience flight, and this new element left him exhilarated, but floundering for a new vocabulary. Gone were the certainties of the distinct sky-line, the contours of the downs and undulations of the fields. In a final, calamitous posting, he was sent to Iceland and joined observational flights above the epic glacial landscape. It was on one of these, in 1942, he went missing, leaving behind his widow, Tirza, who struggled to receive a war pension due to her husband’s ‘disappearance’ rather than death (no body was ever found). Yet deceased he undeniably was, slipping from this world with the same deceptive lightness of his work. He flew into the light and did not return. Upon his death, one of his closest friends, Edward Bawden, said of Eric, that ‘his life was like his art, graceful and long-lasting in its effects.’

Ravilious and his contemporaries ennobled the everyday in their art and design, capturing a sublime expression of conscious and sensibility from the twenties to forties – one that had a texture of realism but with a graceful lightness that danced free of its matrix.

Visiting it with talented friends felt resonant – for in our own pattern of friendship (stretched between Wiltshire, Somerset, Devon, and Gloucestershire and further afield, but converging in the quirky, creative crucible of Stroud) we have a modern microcosm of a similar creative cross-hatch: artists, novelists, poets, musicians, singers, crafters, print-makers, storytellers… In our own little way we are carrying the flame.

Beachy Heady, Eric Ravilious, 1939

With thanks to Kirsty Hartsiotis and Chantelle Smith.

Ravilious & Co: the pattern of friendship, by Andy Friend, is published by Thames and Hudson, 2017

The Pattern of Friendship exhibition is at Compton Verney Art Gallery until 10 June 2018:

http://www.comptonverney.org.uk/thing-to-do/ravilious-and-co/