Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 17

September 11, 2011

Writing for Games

The Writers' Guild of Great Britain has released some very sensible guidelines for games writers. I note with interest a number of things that I have had to hammer into the heads of certain producers, would-be producers and self-styled producers over the last ten years, now set out as gospel entitlements for professional authors, which is all to the good.

I'm not pleased with the setting in stone of "English script by" as a circumlocution for "not translated at all by" or "substandard translation knocked into shape by". But otherwise very nice indeed — a truly useful document.

September 7, 2011

Ill Winds

In late 2007, I was drawing money out of a Kyoto cashpoint at 240 yen to the pound. In the time since then, the relative value of the pound to the yen has fallen a terrifying 40%. What this means, for you and me, is that anything Japanese is 40% dearer. A CD that once cost you £20 is now more like £28. A tenner's sushi is now four quid more.

In late 2007, I was drawing money out of a Kyoto cashpoint at 240 yen to the pound. In the time since then, the relative value of the pound to the yen has fallen a terrifying 40%. What this means, for you and me, is that anything Japanese is 40% dearer. A CD that once cost you £20 is now more like £28. A tenner's sushi is now four quid more.

Obviously, these issues trouble you a lot more if you are spending large amounts of money. One pound on the cover price of the magazines I read each month for NEO's Manga Snapshot isn't going to make that big a difference to me. But if you're an anime distributor, used to writing cheques for six-figure sums, you're going to feel the pinch. If you're mastering or duplicating your DVDs in, say, Poland, you'll be paying more in Euros for what used to be a cheaper option.

But it's an ill wind that blows nobody any good, as a bunch of amateur economists recently realised. In late January 2009, as the sterling exchange rate sank to a shameful 128 yen, a blogger in Japan began posting his musings on grey imports. Blimey, he said, I can buy Monty Python for a fraction of the Japanese price, and have it sent to me from the UK. Come to think of it, I can buy a LAPTOP, too. A different plug on the cable, and I'm laughing!

Initially, activity was timid. A few early adopters broke out their credit cards to see how it might work out. When one of them posted a happy photograph of the battered but solid Amazon UK parcel on his Tokyo doorstep, the floodgates opened.

The first I heard about it was a day later, when a worried anime distributor called to pick my brains. UK online sales of one of his company's titles, which we shall have to call Schoolgirl Milky Crisis, had suddenly, dramatically spiked. Initial elation turned to concern – why was he suddenly rushing to meet orders so much larger than usual? It turned out that the orders were mainly going abroad, and that's when he asked me to dig around on the Internet.

It took less than a minute for me to track down the anime speculators and their excited bloggery. Which only made matters worse, because if I could do it, so could the Japanese licence holder. Many Japanese companies are utterly petrified of this sort of thing. You wish your anime were cheaper? They wish it were more expensive, because grey imports give them nightmares. It was only a few months ago, in this very column, that I was discussing the symptoms of Blu-Ray Blues, whereby a company tries to centralise and standardise all editions of a release into a single Japan-made disc. But if that super-master-disc, containing all language versions, is 40% cheaper abroad than it is in Japan, it would play havoc with a company's Japan-based statistics, economics and decision-making. Domestic sales will always come first for the Japanese, as foreign money, in these credit-crunchy times, is back to being just gravy. This, in turn, will present accountants in a Tokyo office with a sudden desire to force distributors in the UK to raise their prices to discourage Japanese grey-import opportunists!

Of course, if the pound goes up any time soon, everyone will probably just forget about it and chalk it up to economics. What are the chances of that…?

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This article first appeared in NEO #65, 2009.

September 2, 2011

Fools' Gold?

For readers of a certain age, the news that The Mysterious Cities of Gold is returning stirs up memories of hazy autumn days in 1986, rushing home to see the latest instalment of a cartoon series with a difference. MCoG had adventure and action, a complex storyline and believable characters… it was also an anime. MCoG was one of the last of the "hidden imports", Japanese animation shows released in the UK with no discussion of their origins. Four years later, Akira changed everything.

For readers of a certain age, the news that The Mysterious Cities of Gold is returning stirs up memories of hazy autumn days in 1986, rushing home to see the latest instalment of a cartoon series with a difference. MCoG had adventure and action, a complex storyline and believable characters… it was also an anime. MCoG was one of the last of the "hidden imports", Japanese animation shows released in the UK with no discussion of their origins. Four years later, Akira changed everything.

MCoG gets a mention here because the animation was done by the famous Studio Pierrot, including early directorial work from Mizuho Nishikubo, the director of Musashi: Dream of the Last Samurai. But considering that the original was a French co-production (run by Ulysses 31's Jean Chalopin), and there is currently no mention of Japanese participation in the sequel, I may not have cause to mention it again.

MCoG is thirty years old. As is the way with such multinational productions, the ownership of the original was a nightmare. For years, it seemed that the sticking point was the Japanese end of production, with the network NHK refusing to give up its share or sell it on so that others could do something with it. The deadlock was broken in 2007, with Chalopin's new company Movie Plus buying NHK's interest in the franchise, in turn freeing it up to be released on DVD, and indeed, for discussions to begin about a remake.

Initial discussions seemed to centre around a film production, although all mention of that was soon taken down from Movie Plus's website. Instead, these speculations were replaced with an announcement that Mysterious Cities of Gold would be brought back as three 26-episode TV serials, moving the action from South America to Asia – 1532, the setting of the original series, is conveniently close to the samurai warring states period and the peak of China's Ming dynasty.

But even if the setting is Asia, the animation companies listed so far are resolutely French, a fact liable to classify MCoG as a "mere" cartoon. That doesn't mean it won't be great; just that it's likely appeal to fans of Japanese animation will surely be diminished.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This article first appeared in NEO 87, 2011.

August 26, 2011

Manga Kamishibai: The Art of Japanese Paper Theater

Like Brigitte Koyama-Richard, Eric Nash is interested in anime before anime, namely the itinerant storytellers who would rent lurid image boards from central art suppliers, and then bike around Japan's cities in the 1920s to present slideshows of princes from Atlantis, journeys into space and creepy horror stories for rapt audiences of children.

Like Brigitte Koyama-Richard, Eric Nash is interested in anime before anime, namely the itinerant storytellers who would rent lurid image boards from central art suppliers, and then bike around Japan's cities in the 1920s to present slideshows of princes from Atlantis, journeys into space and creepy horror stories for rapt audiences of children.

Killed off by TV in the 1950s, kamishibai ("paper theatre") was a fascinating, vibrant medium in which many future manga artists cut their teeth. Kamishibai storytellers might sound like nothing more than Punch & Judy men, but at the high point of their trade they were estimated to entertain five million Tokyo residents a day – "viewing figures" considerably better than many modern anime. They also presided over the beginnings of many well-known stories, particularly the Skull Man and Spooky Ooky Kitaro tales that went on to find fame as anime and manga. Nash offers intriguing glimpses of this forgotten forerunner to anime, even including wartime propaganda such as Exploits of Military Dogs and an air-raid safety instructional manual. Truly amazing.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This review first appeared in the SFX Ultimate Guide to Anime, 2011.

August 19, 2011

Blue Sky Investments

And we're back in the Tokyo courts as former investment banker Takeshi Matsubara is convicted of insider trading with the details of four Japanese companies, including the anime studio Gonzo, the people who brought you Romeo X Juliet and Hellsing Ultimate. Matsubara was a financier at Aozora ("Blue Sky") bank in 2007, when Gonzo Digimation Holdings struck a secret deal for extra investment from So-Net Capital holdings. Aware of the coming injection of cash, Matsubara rushed out and bought a ton of GDH shares, which shot up in value when the news became official. He sold them off soon after, netting a personal profit of 14 million yen (that's £102,000 in your Earth money).

And we're back in the Tokyo courts as former investment banker Takeshi Matsubara is convicted of insider trading with the details of four Japanese companies, including the anime studio Gonzo, the people who brought you Romeo X Juliet and Hellsing Ultimate. Matsubara was a financier at Aozora ("Blue Sky") bank in 2007, when Gonzo Digimation Holdings struck a secret deal for extra investment from So-Net Capital holdings. Aware of the coming injection of cash, Matsubara rushed out and bought a ton of GDH shares, which shot up in value when the news became official. He sold them off soon after, netting a personal profit of 14 million yen (that's £102,000 in your Earth money).

Unfortunately for him, Matsubara was caught, and now faces a four-year suspended sentence and fines to the amount of quadruple his original profits for daring to dabble in the wacky world of anime financing.

Anime and manga companies are an incredible mess of paperwork. They are founded, declare bankruptcy, and coalesce immediately once more around their old staff. Tokyo Movie becomes Tokyo Movie Shinsha ("New Company"), A Productions becomes Shin A ("New A"). Mushi Productions collapses in a heap, but reveals that most of its copyrights are owned by Tezuka Productions, which can keep trading… and so on. Gonzo ended up buying itself to streamline its funds. Such brinkmanship is an everyday occurrence in the corporate world, and it's a fact of life that some companies fail and others succeed, and also that a "dead" company might have staff, machinery or real estate that's worth recovering from the debt-ridden mess.

Which brings me to the recent demise of Tokyopop, a company that has just shut down in the US, mortally wounded by the collapse of Borders. But Tokyopop has a rack of intellectual property, thanks to draconian rights deals that signed over non-Japanese creators' work to the publisher. It won't be long before Tokyopop titles fade from shelves, but many still exist as ideas that belong to Tokyopop or its successors. One wonders, how much is that intellectual property worth? A hundred comics, perhaps, any one of which might become a movie one day? A video game? Or is it all unsellable dross? As a blue-sky investment, how much would you pay for the Tokyopop backlist…?

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This article first appeared in NEO 86, 2011.

August 12, 2011

Mardock Scramble

Private-eye Dr Easter and his shapeshifting companion Oeufcoque rescue teen hooker Balot from a fiery death, before putting her to work in a campaign to bring down a sinister crime boss. Mardock Scramble is that rarest of opportunities – a chance to read the source material of an anime before most foreign viewers get the opportunity to see the spin-off in a cinema (the anime will be released here in a few months). In a refreshing change from piecemeal publications, US-based Haikasoru have combined an entire trilogy in one monster volume. This not only delivers superb value for money on the page-count, but also avoids the likely loss of readers that would have been likely to have otherwise bailed out during an overlong casino interlude.

Private-eye Dr Easter and his shapeshifting companion Oeufcoque rescue teen hooker Balot from a fiery death, before putting her to work in a campaign to bring down a sinister crime boss. Mardock Scramble is that rarest of opportunities – a chance to read the source material of an anime before most foreign viewers get the opportunity to see the spin-off in a cinema (the anime will be released here in a few months). In a refreshing change from piecemeal publications, US-based Haikasoru have combined an entire trilogy in one monster volume. This not only delivers superb value for money on the page-count, but also avoids the likely loss of readers that would have been likely to have otherwise bailed out during an overlong casino interlude.

Habitual anime viewers will sense strong echoes of Ghost in the Shell in Ubukata's resurrected cyborg protagonist, and also resonances of the sly misogyny to be found in the anime scripts of Chiaki Konaka. Like Konaka, Ubukata wants to have his cake and eat it, presenting women in peril, distress and abusive situations for the titillation of a male readership, while simultaneously inviting disapproval of their plight.

Ubukata also does himself no favours by resorting to the tiresome Japanese habit of naming characters with punning associations in English. Ever since Osamu Tezuka, this practice has rendered uncountable stories seem laughably inept in translation – the author might cackle over the foreshadowings and egg-related references in his subtexts, but they are all too obvious to English readers, and can distract from an otherwise serious narrative, as if Frodo's name were Dave Ring2mordor and Boromir were called Placeholder Deadsoon. Translator Edwin Hawkes does the best he can with such material, resulting in an illuminating window on what is both good and bad about modern Japanese science fiction.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This review first appeared in the SFX Ultimate Guide to Anime, 2011.

August 5, 2011

Tartar Source

Determined to make a trip to the dairy more fun for all the kiddies, the Snow Brand Milk Products company decided it needed a cartoon. The result was Tengri the Boy of the Steppes (1977), a 21-minute promotional film pointing out to people just how tough dairy production was in the bad old days. Set on the plains of Central Asia, it showed scenes in the troubled life of Tengri, a hunter boy who develops a brotherly relationship with Tartar, a young calf. We learn all about life on the steppes, until a fateful winter when Tengri is ordered to kill the calves for food. Unable to bring himself to off his bovine best friend, Tengri "loses" Tartar in the snow.

Determined to make a trip to the dairy more fun for all the kiddies, the Snow Brand Milk Products company decided it needed a cartoon. The result was Tengri the Boy of the Steppes (1977), a 21-minute promotional film pointing out to people just how tough dairy production was in the bad old days. Set on the plains of Central Asia, it showed scenes in the troubled life of Tengri, a hunter boy who develops a brotherly relationship with Tartar, a young calf. We learn all about life on the steppes, until a fateful winter when Tengri is ordered to kill the calves for food. Unable to bring himself to off his bovine best friend, Tengri "loses" Tartar in the snow.

Years later, a grown-up Tartar somehow saves the village, and the previously unknown Recipe for Cheese allows Tengri's fellow villagers to bring aid to the starving. Cheese is the saviour of the steppes, as it allows milk to be preserved long past the date it is extracted from a cow. Consequently, the villagers have food all through the winter, and don't need to kill cattle for meat.

This odd story, seemingly not mentioning that all dairy cattle end up slaughtered for meat, was dashed off by Astro Boy creator Osamu Tezuka at Snow Brand's request. His contribution, described as "a character sketch and a four-page story outline," was thrown at the animation company Group Tac, which sat on it for two years. They were, it seems, rather busy at the time on Manga Fairy Tales and the animated Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. With time ticking away, the project landed at Shin-Ei animation, where animator Yasuo Otsuka finally took it on in what would be his sole directing credit, obliged to crank it out on a 45-day production schedule.

Otsuka was plainly not a fan of Tezuka, a man whom he regarded as largely responsible for the collapse in the quality of Japanese animation. To put things bluntly, while Tezuka readily lapped up any praise that called him "the Japanese Disney", he owed much more in his working practices to the extremely limited animation practices of Hanna-Barbera. Tezuka's production-line system and cost-cutting measures might have made it possible to make anime on weekly television schedules, but they also irredeemably cheapened animation, Otsuka thought. Animators worked hard before Tezuka, but after Tezuka they worked like dogs, in an industry notorious for chewing up its practitioners and spitting them out.

Otsuka was hence not all that impressed with Tezuka's tales of "Tartar source", particularly since he got the impression Tezuka had dashed off a vague story in less time than it took to smoke a fag. Otsuka also had problems with Tezuka's outline, particularly the original Shane-inspired ending where Tengri heads off towards the west, a lone drifter, with the implication being that he takes cheese to Europe, like a dairy Prometheus.

Otsuka began planning a rewrite, only to be told by the producer Eiji Murayama that the ending was "suffused with poetic sentiment" in depicting a hero who "leaves the trifling human world" in order to journey to Europe. Which is, presumably, not populated by humans.

But this was supposed to be a cow + boy story, not a cowboy story. Otsuka understood the elegiac quality, but he thought that a children's film should end with its protagonist welcomed back by the village. Risking the ire of Tezuka and the dairy, he changed the ending by hiding the horizon behind a bunch of cows, so that it wasn't immediately plain to see where Tengri was heading. If you wanted to believe he came home at the end, you could now believe that.

Not that the horizon needed much hiding, as Otsuka had to use standard-sized cels. Despite a setting on the rolling grasslands of Asia, a union rep had told Otsuka there would be no great vistas in the background, as that was too much work for the colorists. Otsuka protested that even staunch union men in the animation business took enough pride in their work to draw a wide plain if a wide plain was called for, but he was overruled. What really wound Otsuka up was that the union had accepted the job, claimed they could do it, and then threatened to walk out when it proved impossible. He'd have preferred it if they'd refused from the outset, so he could have gone back and asked for a budget increase to do a better job.

In the end, Otsuka was forced to sit with his arms folded, sulking bitterly, at the preview screening, as his under-funded anime rolled out to a largely unappreciative audience. People filed out saying that it would "do", and Otsuka – one of the greatest animators in 20th century anime – never directed a film again.

Although some online reviewers on Amazon Japan claim to have seen Tengri the Boy of the Steppes on TV, for thirty years it was officially only available to people who either visited the Snow Brand factory showroom, or rented it out from the dairy as a 16mm film print. But then, a series of events propelled Otsuka's obscure cartoon back into the media.

In 2000, Snow Brand Milk Products achieved a different kind of notoriety when over 14,000 Japanese reported unpleasant side effects of consuming "old milk", past its sell-by date.

In 2000, Snow Brand Milk Products achieved a different kind of notoriety when over 14,000 Japanese reported unpleasant side effects of consuming "old milk", past its sell-by date.

The following year, Yasuo Otsuka discussed the film's production history in his autobiography. In the process, he mentioned something that revealed to Snow Brand they were sitting on a dairy anime goldmine that could help dispel their media milky crisis. As a result, Snow Brand authorised the release of Tengri the Boy of the Steppes as a deluxe DVD in 2007, bringing this forgotten anime back into the limelight once more.

Of course, it probably helped that the new credits acknowledged the contribution of Yasuo Otsuka's young layouts assistant, a previously uncredited young animator called Hayao Miyazaki.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This article first appeared in the SFX Ultimate Guide to Anime, 2011.

July 28, 2011

Sakyo Komatsu 1931-2011

Sakyo Komatsu, the science fiction author best known for Japan Sinks, has died aged 80. In lieu of an obituary, I give you the entry from the upcoming third edition of the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, for which I substantially upgraded Takumi Shibano's entry on Komatsu from the previous edition. You should be able to access the draft text here.

Sakyo Komatsu, the science fiction author best known for Japan Sinks, has died aged 80. In lieu of an obituary, I give you the entry from the upcoming third edition of the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, for which I substantially upgraded Takumi Shibano's entry on Komatsu from the previous edition. You should be able to access the draft text here.

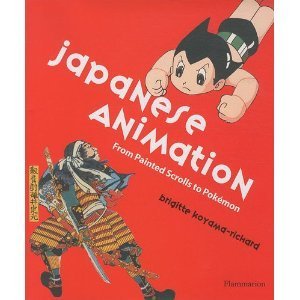

Japanese Animation: From Painted Scrolls To Pokemon

As the title suggests, Brigitte Koyama-Richard's book is heavily concerned with "pre-cinema" – the slow growth of anime from two hundred years of sideshows, optical toys and shadow plays. Although anime flourished in the 20th century, Koyama-Richard crams as much of it as she can into as small a space as possible: it takes her 73 pages to get to Oten Shimokawa's first Japanese cartoon in 1917, and she is in the 1970s only seventeen pages later. This is, however, immensely valuable for its very focus – you can read the story of the twentieth century elsewhere, but Koyama-Richard offers fascinating insights into grotesque Japanese prints and magic lantern shows. The illustrations are rich and informative, although her text is largely unreferenced, and often makes unfounded assumptions, in particular about how "popular" certain shows were – a word that far too many authors, Japanese and otherwise, are happy to sling around with gay abandon. She does, however, have several useful primary-source interviews with figures from many areas of the anime business.

As the title suggests, Brigitte Koyama-Richard's book is heavily concerned with "pre-cinema" – the slow growth of anime from two hundred years of sideshows, optical toys and shadow plays. Although anime flourished in the 20th century, Koyama-Richard crams as much of it as she can into as small a space as possible: it takes her 73 pages to get to Oten Shimokawa's first Japanese cartoon in 1917, and she is in the 1970s only seventeen pages later. This is, however, immensely valuable for its very focus – you can read the story of the twentieth century elsewhere, but Koyama-Richard offers fascinating insights into grotesque Japanese prints and magic lantern shows. The illustrations are rich and informative, although her text is largely unreferenced, and often makes unfounded assumptions, in particular about how "popular" certain shows were – a word that far too many authors, Japanese and otherwise, are happy to sling around with gay abandon. She does, however, have several useful primary-source interviews with figures from many areas of the anime business.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This review first appeared in the SFX Ultimate Guide to Anime, 2011.

July 25, 2011

Toyo'o Ashida 1944-2011

My obituary of Toyo'o Ashida, a crusader for animators' rights and the legendary show-runner on the old Fist of the North Star TV series, is now up on the Manga UK blog.

My obituary of Toyo'o Ashida, a crusader for animators' rights and the legendary show-runner on the old Fist of the North Star TV series, is now up on the Manga UK blog.

Jonathan Clements's Blog

- Jonathan Clements's profile

- 123 followers