Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 15

November 23, 2011

The Thread-Free Sky

Her eyes were green. Her hair was silver, and she freckled. The rest was subject to change without notice.

To a jaded cynic, the work of Anne McCaffrey (1926-2011) was little more than a science fictional repackaging of well-worn tropes from the world of fiction for adolescent girls. She had an entire stable of protagonists modelled on Cinderella or Lisa the Lonely Ballerina, and a whole paddock of tales about ponies and horses, which she rewrote as dragons. I was a ten-year-old boy in 1981; I didn't know that. If I had, I might have turned away with a sneer and bought something about space marines.

Instead, I discovered that there was a place where elegant, terrible, wonderful creatures sought out the purest of heart. Passions and yearnings could wake worlds, knowledge was passed on through songs… imperfectly, poetically… warning that something called Thread would fall from the sky. Old songs, forgotten songs, whispering of apocalypse, ignored, belittled, dismissed. Until the day the songs came true.

The series, as it existed when I first came to it, comprised twin trilogies, one for adults, and one for younger readers, often offering different perspectives on the same scenes and events. And it all came to an end with this:

The dragons on the fire-heights rose to their haunches, bugling their jubilation on this happy day while fire-lizards executed dizzy patterns in the Thread-free sky!

What a sentence. As a teenage would-be author, I fixated on that last phrase. The sky was finally free of Thread, the awful alien mycotoxins that brought ecological disaster; the Dragonriders had found a way to neutralise Thread on contact with the ground. The Dragonriders had rendered themselves obsolete. Their whole world was about to fall apart, and nothing would be the same again. F'lar and Lessa, the reluctant first couple of Pern, walked out of the narrative with smiles on their faces, but they stood at a momentous moment in history, thick with melancholy and pregnant with loss.

Opening my battered, much-read, much-loved copy of the The White Dragon this morning, I turned once more to the sentence I thought I knew so well. Just try reading it out aloud. It is breathless and giddy, arguably missing a comma and ending in a grandstanding exclamation point. You would need to be an opera singer to belt that sentence out and get it in all its passionate, gabbled glory. Anne McCaffrey, who once was an opera singer, and often wrote as if translating music into prose, ended her masterpiece on a crescendo and a descant.

Sadly, perhaps, it wasn't the end. I would read the first six Pern novels on an almost annual basis, but I had little time for the diminishing returns of the later bolt-ons. I liked Dragonsdawn, with its revelation that McCaffrey's world was a sci-fi acronym: Parallel Earth Resources Negligible. I was intrigued by Moreta: Dragonlady of Pern, and not only for its glimpse of a legend only whispered in the main saga, but also for its engagement with something only obliquely referenced in earlier books – the fact that a number of the dragonriders were gay. But I had no time for the rest of it: the Celtic whimsy and the pointless dolphins, the previously unmentioned gipsies and the inevitable aging and changing of the characters I loved.

As I protested to my fannish friends, all largely aghast at my passion for a girl's book, it's all there in the last sentence of The White Dragon. They're dancing in the Thread-free sky. Game over. Do we really want to see them building factories and laying roads? Must we watch them bickering, growing old, dying? The tale is told.

When All the Weyrs of Pern was published in 1991, I was living in Taiwan, and had no hope of finding a copy. In early 1992, I met an American girl in Japan who had the audio book. After resisting for weeks, I put the tape in my Walkman, and lay there in the dark, listening to the big finish. It was read by McCaffrey herself.

She stumbled over the characterisation of minor characters. She blundered around in a forest of adverbs. I seethed, throughout, at the clear proof of my Thread-free Sky thesis. Like all fans, I wanted more, more, more, even though I knew that more was not necessarily for the best. And then she got to a moment when a major character, a unifying figure in the saga as a whole, a mentor to many and father-figure to a few, died. McCaffrey was having trouble reading her own book, her breathing came in weird places, and I realised that she was trying not to cry. When death finally came, she stopped reading and wept.

I love Anne McCaffrey, for loving her own story so much that it moved her to tears. I will always be grateful to her because I went into the newsagent next to Prittlewell railway station, on my way home from school in 1981 and came out with a book about men riding on dragons, instead of the previously desired bar of chocolate. I love her because I adored Dragonflight so much that I dragged my stepmother into That Fancy London to buy the rest of the books at the hallowed Forbidden Planet – a store I had never been to before.

I learned from Pern that it was okay to take what you wanted from an author and leave the rest. I learned the joys of hunting for the next book in a series and staying up late to find out what happens to imaginary people you've come to care for. I learned to describe a particular colour as Harper Blue. That it was okay to grow up and move on, and look fondly on books you treasured as a child. When The Skies of Pern came out, I decided I was not going to read it. I had my Pern, and I kept it. I read the first six books again, because they had a real something, and that something ended with the Thread-free sky.

Ron Moore saw it. In Pern he saw a metaphor for a nation under siege, a hopeless, doomed conflict against an implacable enemy, a mid-holocaust tale of humanity on the brink of extinction. When his Pern TV series was announced sometime around the turn of the century, I was a twenty-something editor at Titan, a company bidding for the rights to do the tie-in magazine. David Bailey had already decided that he was going to be the editor. I immediately volunteered to be his deputy. We began addressing each other as D'vid and J'nathan, using McCaffrey's honorific median apostrophes, much derided among serious SF fans, and to the great irritation of our colleagues. But the TV series never happened. In conflict with his bosses, Moore walked off it with the sets already built, proclaiming that he would do it right or not at all. Instead, he made Battlestar Galactica.

James Cameron may have seen it, too. Even if he didn't, I did. I sat through Avatar with a giant, stupid grin on my face, not seeing the film that he had made, but the film that was to come. This is it, I thought as men on flying lizards fought in the air. We can finally do it. We can do Pern.

You can keep your sparkly vampires and your boy wizards. One day, Pern is going to wipe the floor with them. But today there is an eerie, hair-raising, barely audible, high keening note, that signifies the passing of one of our kind.

November 18, 2011

There You Go, Astro Boy

It's taken me a while to get to Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas, thanks largely to a £30 cover price. But I got there in the end, and my review of it is now up on the Manga UK blog. It's great to have such solid information from Fred Ladd about the first ten years of the anime localising business, although I can live without the latter half of the book and its vague hand-waving about what happened next. That said, it's still worth every penny, if only for the 100 pages of golden testimony about the way in which Japanese cartoons were treated in the TV industry of the 1960s and early 1970s.

It's taken me a while to get to Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas, thanks largely to a £30 cover price. But I got there in the end, and my review of it is now up on the Manga UK blog. It's great to have such solid information from Fred Ladd about the first ten years of the anime localising business, although I can live without the latter half of the book and its vague hand-waving about what happened next. That said, it's still worth every penny, if only for the 100 pages of golden testimony about the way in which Japanese cartoons were treated in the TV industry of the 1960s and early 1970s.

November 15, 2011

Hello, Sailors

The Mariner's Mirror, or to give it its fantastic full title, The Mariner's Mirror, wherein may be discovered his art, craft & mystery after the manner of their use in all ages and all Nations, has just published a glowing review of my Admiral Togo: Nelson of the East. Alessio Patalano, lecturer in War Studies at King's College London and a specialist in East Asian security issues, really gets the book, noting its concentration on "the multiple applications of naval power, from diplomatic to constabulary and military functions." This is particularly important in the case of Togo, as there was considerably more to his life than his sudden appearance in 1905 as the hero of the battle of Tsushima. He'd first encountered the British as a teenage samurai, and watched swordsmen standing knee-deep in water on the shores of Kagoshima, angrily brandishing their blades at "retreating" Royal Navy vessels. He'd studied for several years in Victorian England, and been part of dockside politics and naval espionage in China, Korea, and Hawaii before he saw military action against China and Russia. Patalano thinks, rightly, that I have romanticised Togo, but also notes: "This book is a refreshing account of a defining figure of modern Japan. It is well written and deals with themes such as leadership, individual commitment, social transformation and cross-cultural understanding of great contemporary relevance."

The Mariner's Mirror, or to give it its fantastic full title, The Mariner's Mirror, wherein may be discovered his art, craft & mystery after the manner of their use in all ages and all Nations, has just published a glowing review of my Admiral Togo: Nelson of the East. Alessio Patalano, lecturer in War Studies at King's College London and a specialist in East Asian security issues, really gets the book, noting its concentration on "the multiple applications of naval power, from diplomatic to constabulary and military functions." This is particularly important in the case of Togo, as there was considerably more to his life than his sudden appearance in 1905 as the hero of the battle of Tsushima. He'd first encountered the British as a teenage samurai, and watched swordsmen standing knee-deep in water on the shores of Kagoshima, angrily brandishing their blades at "retreating" Royal Navy vessels. He'd studied for several years in Victorian England, and been part of dockside politics and naval espionage in China, Korea, and Hawaii before he saw military action against China and Russia. Patalano thinks, rightly, that I have romanticised Togo, but also notes: "This book is a refreshing account of a defining figure of modern Japan. It is well written and deals with themes such as leadership, individual commitment, social transformation and cross-cultural understanding of great contemporary relevance."

November 11, 2011

Three Today

The Schoolgirl Milky Crisis blog is three years old today. I'm going to keep posting stuff here until Titan Books grow bored with it. They will continue to think of this blog as a worthwhile expense for as long as people are buying the Schoolgirl Milky Crisis book, either here in the US, or here in the UK. So please do consider it as a Christmas present for your odder uncle or more eccentric aunt, that irritating sibling or that strangely with-it parent. Or even for yourself.

The Schoolgirl Milky Crisis blog is three years old today. I'm going to keep posting stuff here until Titan Books grow bored with it. They will continue to think of this blog as a worthwhile expense for as long as people are buying the Schoolgirl Milky Crisis book, either here in the US, or here in the UK. So please do consider it as a Christmas present for your odder uncle or more eccentric aunt, that irritating sibling or that strangely with-it parent. Or even for yourself.

November 9, 2011

Primul împărat al Chinei

My book, The First Emperor of China, is now available in Romanian, which I am sure is a great relief to all of you. It's been published by Editura All in Bucharest with a nicely understated cover and has already got a glowing review from the film website Filme Carti, which clearly appreciates my appendix on the First Emperor's screen appearances. Since Editura All also translated my biography of Confucius, I can only hope they are now moving on to Empress Wu.

My book, The First Emperor of China, is now available in Romanian, which I am sure is a great relief to all of you. It's been published by Editura All in Bucharest with a nicely understated cover and has already got a glowing review from the film website Filme Carti, which clearly appreciates my appendix on the First Emperor's screen appearances. Since Editura All also translated my biography of Confucius, I can only hope they are now moving on to Empress Wu.

November 4, 2011

November 2, 2011

Korea Advice

The London Korean Film Festival starts today. In its honour, I point you at a few of the Korean entries I have written for the as-yet unfinished Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: the alternate universe dramas 2009: Lost Memories and Goong, and the author entry on Bok Geo-il. I'm supposed to be concentrating on Chinese and Japanese entries, but every now and then I get distracted… either by Korea or by something that seems like an omission, such as the entries on Roberto Bolano and Chuck Palahniuk. If an entry has "[JonC]" at the bottom, it's one of mine.

November 1, 2011

Museum Piece

My review of Yukinobu Hoshino's Professor Munakata's British Museum Adventure is up now on the Manga Entertainment blog. I don't think I have ever seen an institution spend its junket money in a more productive way. The BM managed to get a ten-issue manga series read by tens of thousands of Japanese readers, and now this massive advert for what the BM is and what it means for the people of the UK. All because they invited the right artist at the right time, and made sure that he went home inspired. Now, if they'd invited Toshio Maeda…

My review of Yukinobu Hoshino's Professor Munakata's British Museum Adventure is up now on the Manga Entertainment blog. I don't think I have ever seen an institution spend its junket money in a more productive way. The BM managed to get a ten-issue manga series read by tens of thousands of Japanese readers, and now this massive advert for what the BM is and what it means for the people of the UK. All because they invited the right artist at the right time, and made sure that he went home inspired. Now, if they'd invited Toshio Maeda…

October 25, 2011

Speculative Japan 2

Although cover, front page and spine are all in disagreement about this book's exact title, it contains stories of SF and fantasy from Japan, many lifted from a 2006 best-of survey. The oldest story here is Naoko Awa's  fairytale "A Gift From the Sea" (1977), while the most recent are a bunch from 2007. Clustered among them are superlative works such as Yasumi Kobayashi's super-hard SF "The Man Who Watched the Sea" (2002) and Issui Ogawa's "Old Vohl's Planet" (2003), a first-contact tale told by the last survivor of a race of creatures from a gas-giant planet. There is a wide range of tone and quality in both stories and translations – one tale inadvisably attempts to make Japanese-speaking space-farers speak like 1930s English sea dogs, while another is a superlative translation of a sub-standard sentimental romance. But in bringing thirteen Japanese authors to the attention of a wider English-speaking audience, this is one of the most important contributions to Japanese prose SF abroad in the last twenty years.

fairytale "A Gift From the Sea" (1977), while the most recent are a bunch from 2007. Clustered among them are superlative works such as Yasumi Kobayashi's super-hard SF "The Man Who Watched the Sea" (2002) and Issui Ogawa's "Old Vohl's Planet" (2003), a first-contact tale told by the last survivor of a race of creatures from a gas-giant planet. There is a wide range of tone and quality in both stories and translations – one tale inadvisably attempts to make Japanese-speaking space-farers speak like 1930s English sea dogs, while another is a superlative translation of a sub-standard sentimental romance. But in bringing thirteen Japanese authors to the attention of a wider English-speaking audience, this is one of the most important contributions to Japanese prose SF abroad in the last twenty years.

Jonathan Clements is a contributing editor to the new edition of the Encylopedia of Science Fiction, with special responsibilty for Chinese and Japanese material. This review first appeared in the SFX Ultimate Guide to Anime, 2011.

October 23, 2011

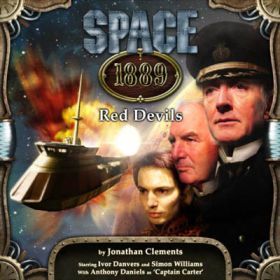

Party Like It's 1889

Over on his blog, Andy Frankham interviews John Ainsworth and me about our work on the Space 1889 audio dramas. I can't believe it's already been six years since they came out.

Over on his blog, Andy Frankham interviews John Ainsworth and me about our work on the Space 1889 audio dramas. I can't believe it's already been six years since they came out.

Doing this reminds me I must write up my discoveries on Japanese steampunk soon. There are some really amazing stories I uncovered while working on the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, including Rhett Butler vs samurai and Byron's daughter in space.

Jonathan Clements's Blog

- Jonathan Clements's profile

- 123 followers