Raph Koster's Blog, page 19

May 18, 2013

The Sunday Poem: Descending to the Airport at Night

It has been a very long time since I posted a Sunday Poem. I am about to get on another airplane in the morning, so I am posting it a day early.

This one’s bones came to me on a return flight from up the California coast, seeing the marine layer hovering at the edge of the ocean. It sat tall, far taller than any of the hills or cliffs. It looked a cliff itself, a glacier, maybe The Wall from Game of Thrones, overhanging the land. It looked like a shoreline in an inverted world where everything we are was lost in the dark except the little twinkling lights.

Seeing the clouds as an ocean is hardly new, of course, but it stuck with me as we descended. I thought about the liminal perspective a plane affords, an upbringing affords, and recited phrases to myself, trying to commit them to memory before they darted away like nervous fish. It has seen minimal revision from that version, scribbled onto an iPad in the airport parking lot.

Descending to the Airport at Night

Marine layer fog a glacier over cities:

For once the sea is higher than the land.

This is the deepest darkest ocean trench,

our plain, our towns, drowned in atmosphere.

We move insensible upon this sea bed

as fluorescent, incandescent fish.

Scattered jewels, sodden treasure jostled

by unknown eddies, unscoped physics,

the science of the currents, systems of

the waves, the sins of sociology,

the breathless and the brave reduced to just

a coral-tracing spattering. A crust.

Salmon coursing off to breed,

Salmon coursing off to breed,

a billion gaping mouths to feed,

territories mostly small,

traces barely there at all

once abrading water has its way

and softens all our brights to gray.

From this all life was born.

The sum. The sea. The salt.

We gasp, we dart. We flow.

Exalt.

Under microscope, from a beachhead far away

We are each as special as a grain of sand.

We are each as special as a grain of sand

Under microscope.

May 9, 2013

On personal games

I don’t have any tales of games saving me from depression.

I mean, I did go through a period where I was depressed. I dropped out of high school while living overseas and basically just didn’t go anywhere. I slept for 23 hours straight. I woke up to eat something and read. It was listlessness, pointlessness, it was like a blank. I didn’t feel sad. I felt… absent. Eventually I was dragged to a doctor who basically prescribed sunshine and a lot of vitamins, and a swift kick in the ass.

The terror of reintegrating into life was enormous. I was shaking and trembling as I caught the bus to downtown. Walking onto the campus had me breathless. And the perfunctory disbelief as I tried to explain to the school administrators what had happened was shocking: idle curiosity married to not caring. Their response to my terror was to say “well, just go back. It’ll be hard.” It was. And it comes back, every once in a while, though never as bad.

But games didn’t save me from that.

I don’t have any tales of games being my lifeline as an outsider.

I mean, I did grow up an outsider in many ways. I was an unusually smart half-Latino kid in a rural New England town. My grandfather, still in some ways the Puerto Rican campesino, cultivated an enormous garden. Maybe it would be better to term it a small farm. He played the Venezuelan cuatro on the porch, and hung a woven hammock there. My mother told me that there were sometimes racist remarks, but I don’t remember hearing them. I was reading adult books when I was two. The teachers loved me, but the older kids would challenge me to spell p-s-y-c-h-i-a-t-r-i-s-t while we waited for the buses to take us back home. This is the time that shapes my personal mythology, the idyll of me.

Then uprooted at age nine, to South America, where I did not speak the language, where men with machine guns guarded the street corners, where mysterious crumbling sand temples full of buzzing bees and potsherds sat next to my elementary school. The teachers loved me again, but also said things in class like “well, the one thing I’ll say about the gringos, they work hard. Much harder than we do. Look at this kid here.” I didn’t get it, I was blowing off all the schoolwork I could. I’d rather stay home and try to master BASIC on my Atari 8-bit.

I was there six years, a gringo in a country that was fighting corruption and communists. They blew up the Pizza Hut. They blew up the Kentucky Fried Chicken. They blew up the mall where the only arcade was. I saw the cardboard and corrugated metal places where they lived. I couldn’t really blame them. Riots and bombs were kind of like the weather. I scavenged for videogame magazines at newsstands and begged my mother to pay through the nose for them. I made boardgames by the dozen, and played AD&D with my small circle of friends. When I left six years later, I was given a farewell packet of notes and letters from dozens and dozens of schoolmates, and it profoundly shocked me. These kids were my friends?

But then I was in another country. A white kid in a black country in the Caribbean, this time, a country where the white kids were all surfers or visiting on vacation. This was where I dropped out. (I wonder now, briefly, if it was because it was expected of me.) I had five friends. We would cut our mandatory sports classes where we had to learn cricket, in favor of sneaking off to the computer lab and playing games. I didn’t make boardgames for them, and I was spending my time writing instead of programming. There were no machine guns at all; my greatest fear was the barracuda in the water as we dove off the jetty, the cops stopping us on our unlicensed bikes.

But then I was in another country. Now, without having changed our income at all, I was a very rich kid in a very poor place: still white, I suppose, though we spoke only Spanish at home. Now the men with machine guns were guarding us, and our cute little white condos perched on the side of the mountain. I sipped piña coladas served poolside when I was fifteen, listening to the drums of vodoun across the valley. I had no teachers – all the schools were closed, and it was too dangerous to leave the compound. Oddly, someone who knew my best friend from Peru happened to move in. It was my first lesson in how incredibly small the world really is, when measured from human to human and not mile to mile.

Years later, that place was pancaked by a massive earthquake. The woman who cleaned the little condo, who came to help us when our first child was born, was never heard from again. I saw the aerial photos. I am sure the drums still play.

Then I moved. Then I moved. I married, and then we moved. Then we moved. Then we moved. I became a new person every time.

I have never made a game about any of these things.

They call people like me “third culture kids.” You’re probably a gamer, so I can try to tell you that it is like adjusting your FOV in a first-person shooter. I live wide. Most people live narrow. But so what?

None of this is special. Some of it is personal – and believe me, I have left out affecting, scary, heartbreaking, and charming stories. But games didn’t pull any of them out of me. I hesitate to share them with those who share so much of themselves in their games, because, well, why? Having a wider FOV means knowing exactly how little a bomb here, an earthquake there, a man with a machine gun, or a piña colada really matter. Knowing how everything is not special means knowing very well how not special you yourself are.

There’s a lot of discussion lately about the ways games mean, the Whats they can mean, the Who’s they reveal. A lot of discussion about the Whys. A lot of it has been personal. We all have our personal.

Right now, I find myself really wanting to make games, and more, really wanting to make games that aren’t actually very personal at all except in the way that any game I would make is personal, and feeling inadequate because I did not tell you the above stories in a game. Like it’s somehow being an artistic poser to not have shared these things in that way. Like telling my (not very special) stories is a price of entry — and yet, they’re not very special, so they are like offering up a pocketful of paperclips and rubberbands when everyone else is proffering shiny coins. Like I shouldn’t even engage in the conversation, because I see personal games being made that humble me.

I find myself wanting to make games that are not what I have made before, that effectively will leave behind the friends I made in another country.

To some degree, it makes me feel listless. Blank. Pointless. Paralyzed. Like I need a swift kick in the ass. Maybe some vitamins and sunshine.

I don’t have any tales of games saving me; except that it’s obvious now that games were glue, a thing that held me to other people, even if only briefly, while everything swirled.

I have made games about the ways in which we are all connected. About the ways in which we get along and don’t get along. About the marvels we can make when we work together. About finding your footing in a world where you can do anything. About the ability to carve a place of your own from a foreign land. About not being pinned down to an identity. About the startling ways in which we are all the same, that so often outweigh the differences. I shouldn’t actually even say what they were about, I suppose. To say it is to betray it, almost.

Making glue is just fine. I think maybe it’s what I have always done, in making games. I don’t need to get personal to make glue.

And so, I move.

This was written as a (personal) response to a few things circulating lately, especially

This was written as a (personal) response to a few things circulating lately, especially

Darius Kazemi’s “Fuck Videogames”

Ian Bogost’s response “Doing Things is Okay”

and especially Frank Lantz’s comment on it

May 3, 2013

1stGameEver videos

Remember back when I posted up that YouTube video of my first game? Well, that video was made for a panel at PAX East.

The panelists have now launched a 1stGameEver Channel with more videos from other developers coming out regularly. First up? Will Wright.

You can also catch video of the full panel at PAX here.

April 29, 2013

GDC Next call for submissions

The call for submissions for GDC Next is now open. I am on the advisory board.

The conference will be in Los Angeles, November 5-7. This is the conference that is replacing GDC Austin; basically, it’s intended to be the most forward-looking of the GDCs, intentionally looking at what comes next, not what happened in the last year. Because of that, the tracks aren’t quite what one would expect:

The Future of Gaming is going to focus on things like second screen play, new kinds of play around mobility, episodic, and the like.

Next Generation Game Platforms will be digging into not just next-gen consoles but stuff like VR headsets, and glasses, microconsoles, motion tracking, smart TVs, watches, and whatever else looks like it is around the corner.

Smartphone and Tablet Games is a bit more here and now, but given the enormous worldwide growth that still remains ahead of these platforms, there’s plenty of cutting edge stuff to discuss, and current lessons to share

Cloud gaming will talk about game streaming — the tech, the business, the design

The Independent Games Track — we all know that indies are where the future lies. Lecture, postmortems, rants, covering design, business, and everything else.

We’ve got a mix of folks from the GDC Austin board plus a bunch of new advisors.

Go submit your talks!

April 26, 2013

Worch explains (some of) the game culture wars

This video by Matthias Worch is superb, an explanation of the communication gap that was exposed so sharply by “A Letter to Leigh.”

“Talking to the Player – How Cultural Currents Shape and Level Design” | You Got Red On You.

In short, after seeing this, it feels like I have been arguing very much from a combination of the oral tradition and the digital culture — likely because of my background in online games. And the aesthetics of print culture are pretty much exactly the things I was commenting on seeing.

In fact, the latest two responses basically argue that games are print culture:

I wonder whether player agency, as we know it, this quality we assume games just naturally have, is actually an illusion.

Raph’s analogy of games as conversation fails for the most part because it is so rare to see a game redesigned after the wide release…

This second quote is telling! I take patch cycles, community response, all that so much for granted that I had to stop and re-read that sentence because it didn’t make sense to me. And similarly, Andrew saying it is rare means that he’s not seeing the way in which games-as-a-service are not only taking over, but will soon be everything.

Worch leans towards print culture himself; the fact that Dishonored is on the agency end of the spectrum in his mind is very telling as well. There’s a certain assumption that being 3/4 of the way over on the spectrum is the default mode, sort of. But he does cover, as an appendix, the consideration of online games and similar emergent spaces — stay past the apparent ending.

For those just catching up on this whole thing, here’s every link I can find, in rough chronological order. Be sure to read the comments too, because it is there that the communication gap is most clearly exposed.

A Letter to Leigh – me

Definitions - Leigh Alexander

A Letter to a Letter – Robert Yang

We have an empathy problem – Adam Saltsman

Formalism and Zinesters: why formalism is not the enemy – Tadgh Kelly

How to Talk About a System and Who Gets To (everyone) – Andrew Vanden Bossche

John Brindle Rocks Out – a series of tweets by John Brindle

What’s in a game? – Devin Wilson

Triptych – Mattie Brice

Que es mas macho? – Colleen Macklin

Board stiff with formalism – Jeremy Antley

A case study in how revolutionaries became The Man – Dan Cook

Resetting definitions – Twitter discussion with me, Zach Gage, and Ed Key

Playing with “game” – me

Raph Koster seems to be doing the impossible – Zoya Street

The Tyranny of Choice – Andrew Vanden Bossche

On games and choice – Twitter discussion with me, Andrew Vanden Bossche, and Andrew Doull

On choice architectures – me

The sandbox has walls – Dan Cox

ggoDbye – Andrew Doull

I am sure I missed more that are out there!

I am rather drifting away from this topic at this point, because I need to get this book revision done and get to working on making games. But I do want to leave some concluding personal thoughts on the table:

The discussion did, in fact, have all the signs of a culture clash. I wish it had focused early on on the actual culture clash, rather than conflating so many threads, but ah well.

I stand by the idea that we’re all being too quick to take something as an attack rather than a conversation.

I’m very thoroughly a product of print culture, myself. In fact, I am overeducated in it, with formal training in many of the arts. It is possible to have a foot in both camps.

Formalism isn’t going anywhere. But we who are interested in it can both fortify our work and avoid political implications by moving to new terminology.

Formalist approaches and reader-response type stuff can easily co-exist.

Whatever the current critical currents are, they will get turned over. Whatever current thought is, it’s not “the right answer.” I’ve seen them turn over too many times.

The increased diversity of voices in the game industry is an incredibly good thing.

I think the work being done by creators like Anna Anthropy, Porpentine, and so many others is brilliant, wonderful, and I don’t really care whether it’s “a game.” I don’t even care much whether a creator chooses to do their work on the print culture end of the spectrum, and when they do I am happy to listen. Since I do not want them to at all feel like I am attacking them, and in fact am a supporter of their work, I am simply going to refrain from critique or discussion that seems unwelcome, even though I really want to write about these games because I find them the most exciting stuff going on right now. Don’t expect me to stop linking to them though, because I really do want more people to see and play them.

I do care about craft elements like whether something is a ludic artifact, because it helps me (and others) make better games.

In the end, I think that despite so many people saying “this is a pointless conversation” that the opposite is true. I found it very stressful, but incredibly worthwhile.

Now, go watch Matt’s video, because it really does put all this is in a different light. I find it ironic that the talk was delivered during GDC, before any of this debate kicked off!

April 24, 2013

On choice architectures

Yesterday Andrew Vanden Bossche posted a great article called The Tyranny of Choice in response to the formal questions about narrative that were in my post A Letter to Leigh.

In the article, Andrew argues that every system by its very nature is a statement, not a dialogue. After all, if we artificially control the boundaries of the system, then every system imposes a worldview. (This is the same argument made about how the original SimCity espoused liberal politics through its simulation).

There are not some games that subvert player agency, and others that grant it. Rather, all games, by nature of being games, by nature of being systems, inherently restrict player agency in the exact same ways. The difference between the games with this “aesthetic of unplayability” (as Koster calls it) and any other game is nil. Other games are merely better at hiding their true nature.

…I question whether there is a difference at all between this games that subvert and refuse player agency and those that encourage and celebrate it. I wonder whether player agency, as we know it, this quality we assume games just naturally have, is actually an illusion. Koster implies that games are capable of create dialogue with their systems; I believe games can only make statements.

This led to a great little discussion with Andrew and also with Andrew Doull, which I have captured as a Storify post here.

It led me to think a bit about architectures of choice. As Andrew Vanden Bossche put it, “if a ‘fake’ choice is as meaningful as a ‘real’ one, is there a difference?”

These are all matters of degree, of course. A work is built out of many moments of interaction (and lack of interaction). A given moment may have immense freight of meaning carried by qualities other than the choice architecture (graphics, storytelling, words, music, and so on).

A long time ago, I did a presentation about two models for thinking about narrative in games. One is the impositional narrative, the case where the author is imposing a worldview firmly on the player. The other is the expressive narrative, where the player imposes a worldview on the system, within the system’s limits. We can also think of these as the narrative created a priori and the narrative created post facto, as storytelling versus mythologizing, as plot versus memory. (Later this was developed into a much more robust framework called the storytelling cube; alas, this presentation requires IE to view right now).

I agree with Andrew that games are always statements. But emergence, user-generated content, chaotic systems, and yes, even our universe are also systems, and they are systems rich enough to allow for what I would personally term dialogue within a system – even if those systems are limited in ways that convey a message. I say that based on my experience creating emergent systems in online worlds, where players continually surprised me by responding to and with the system in ways that I certainly did not foresee. In effect, they expanded the boundaries of the system themselves.

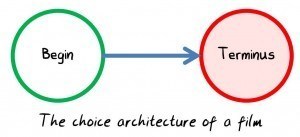

A whirlwind tour of choice architectures might start with a film. The viewer does always have more choice than shown in this diagram, of course; they can get up and leave, they can throw popcorn at the person in front of them, they can shout “fire!” in the theater. But we can think of these as both always-present and un-architected choices. They are all essentially forms of breaking the contract between the viewer and the filmmakers.

Really, what you are “supposed” to do is sit back and absorb. There’s plenty of room for interpretation here, of course, but on a semantic level, not a systemic level. The systemic level does not admit of choices.

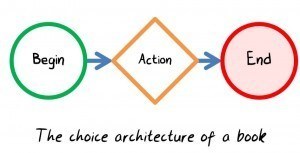

A book is somewhat more interactive. You have to turn a page. But it really doesn’t matter how you turn the page, you’re going to get to the same place. Again, the individual’s experience along the way may be very different thanks to other media, but the systemic artifact itself is very simple, and not particularly open to interpretation.

A book is somewhat more interactive. You have to turn a page. But it really doesn’t matter how you turn the page, you’re going to get to the same place. Again, the individual’s experience along the way may be very different thanks to other media, but the systemic artifact itself is very simple, and not particularly open to interpretation.

There have been efforts to change this. Alain Robbe-Grillet write in an intentionally fractured style. Ezra Pound basically pushed the equivalent of hypertext links on readers of his poetry. Carolivia Herron’s Thereafter Johnnie suggests in its text an alternate order in which to read the book. Julio Cortázar’s novel Rayuela (translated as Hopscotch) plays with the actual form:

An author’s note suggests that the book would best be read in one of two possible ways, either progressively from chapters 1 to 56 or by “hopscotching” through the entire set of 155 chapters according to a “Table of Instructions” designated by the author. Cortazar also leaves the reader the option of choosing his/her own unique path through the narrative.

This is also not dissimilar to the QTE in games; after all, the price of failure on a QTE is generally a sudden death moment, the end of a story. It is a degenerate narrative, one where it is clear that going on is the main current.

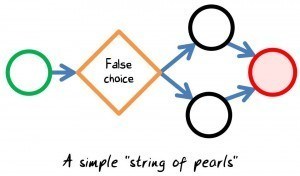

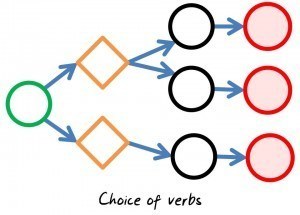

A very common way of dealing with the issue of agency in AAA games is to use the narrative structure termed “string of pearls.” In its simplest form, this is providing the player a number of choices in how to resolve a situation, but collapsing all those choices down to one actual consequence (usually, success in getting past an obstacle). This allows the player to feel real agency moment to moment, while retaining control of the story in authorial hands.

A very common way of dealing with the issue of agency in AAA games is to use the narrative structure termed “string of pearls.” In its simplest form, this is providing the player a number of choices in how to resolve a situation, but collapsing all those choices down to one actual consequence (usually, success in getting past an obstacle). This allows the player to feel real agency moment to moment, while retaining control of the story in authorial hands.

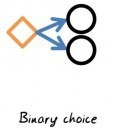

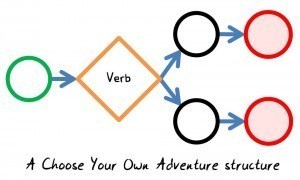

Multiple endings puts a structure in the realm of the Choose Your Own Adventure. Here is the first time we see choices having actual consequences, which also means it is the first time that the author is ceding consequential control to the player. Here for the first time the player constructs not only their own narrative, but their own story. Of course, it is within a rigid structure still, and every possible story has been planned out in advance by the author.

Multiple endings puts a structure in the realm of the Choose Your Own Adventure. Here is the first time we see choices having actual consequences, which also means it is the first time that the author is ceding consequential control to the player. Here for the first time the player constructs not only their own narrative, but their own story. Of course, it is within a rigid structure still, and every possible story has been planned out in advance by the author.

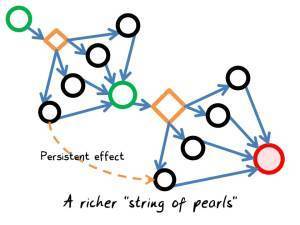

The modern AAA game is actually more a hybrid of “string of pearls” and CYOA. In more complex forms of “string of pearls,” we see that the choices within the “pearl” can be quite rich. But the system still narrows down repeatedly to choke points, where previous choices are shown to have little consequence. In the best games that use this structure, such as Dishonored, there are long-term effects from making choices within the pearl, that manifest as ripple effects as you advance through the game (often presenting the player with multiple endings). But again, at the higher level of structure, the endings are pre-written, and the player is usually being given a binary choice, or perhaps a few choices of endings.

The modern AAA game is actually more a hybrid of “string of pearls” and CYOA. In more complex forms of “string of pearls,” we see that the choices within the “pearl” can be quite rich. But the system still narrows down repeatedly to choke points, where previous choices are shown to have little consequence. In the best games that use this structure, such as Dishonored, there are long-term effects from making choices within the pearl, that manifest as ripple effects as you advance through the game (often presenting the player with multiple endings). But again, at the higher level of structure, the endings are pre-written, and the player is usually being given a binary choice, or perhaps a few choices of endings.

In Colossal Cave there is a famous puzzle where you have to kill a dragon. You try every object you have: a sword, a knife, a bird… nothing works. If you just try KILL DRAGON, the game snarkily replies “With what, your bare hands?”

The answer to the puzzle is, of course, “YES.”

The dividing line between ludic artifact and branching story may lie in the distinction between a choice and a verb. Enabling players to choose not between “means of killing” but between “killing” and “befriending” is where richness really starts to come in, and where the best AAA games operate today. I have to think on this more, but in game grammar terms, a given game atom or ludeme (pick your term!) is recursive, it nests. So something like “kill” is in itself “a game” in the sense that it is a ludic artifact itself, capable of being extracted from the larger system and played on its own.

The dividing line between ludic artifact and branching story may lie in the distinction between a choice and a verb. Enabling players to choose not between “means of killing” but between “killing” and “befriending” is where richness really starts to come in, and where the best AAA games operate today. I have to think on this more, but in game grammar terms, a given game atom or ludeme (pick your term!) is recursive, it nests. So something like “kill” is in itself “a game” in the sense that it is a ludic artifact itself, capable of being extracted from the larger system and played on its own.

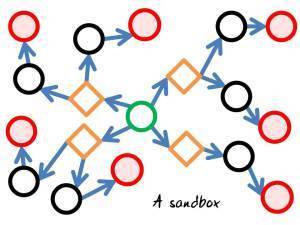

A sandbox game, like The Sims (the original), Grand Theft Auto, Ultima Online, or Minecraft, offers a profusion of verbs at any moment, and has very little authorial push down a single path. Rather than proceed linearly, it sprawls like a jellyfish dropped on concrete (and is often just about as coherent). Players are now much more in the authorial role in that they truly are driving both narrative and story here.

A sandbox game, like The Sims (the original), Grand Theft Auto, Ultima Online, or Minecraft, offers a profusion of verbs at any moment, and has very little authorial push down a single path. Rather than proceed linearly, it sprawls like a jellyfish dropped on concrete (and is often just about as coherent). Players are now much more in the authorial role in that they truly are driving both narrative and story here.

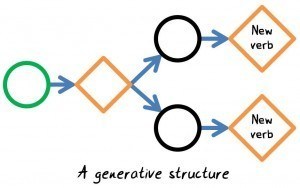

Most importantly, it is at the high end of this structure that we find games like most MMOs, Nomic, Calvinball or Dwarf Fortress, where the actions of players do not just result in the system spitting back a bit of static content, but completely new verbs that exist only because the player put them there. In effect, games where the players create new rules, usually through programmability, emergent behavior, and user-generated content. Now we are in the realm of games where it is the player who makes the art.

Most importantly, it is at the high end of this structure that we find games like most MMOs, Nomic, Calvinball or Dwarf Fortress, where the actions of players do not just result in the system spitting back a bit of static content, but completely new verbs that exist only because the player put them there. In effect, games where the players create new rules, usually through programmability, emergent behavior, and user-generated content. Now we are in the realm of games where it is the player who makes the art.

Now, all the above is excessively reductionist. For example, not all verbs are created equal.

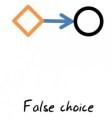

Some verbs are structurally false choices even though they have the trappings of great consequence; a QTE might be one such. We might think of this as the equation “2 = 2.” These sequences evaluate to “true.”

Some verbs are simple binaries, such as the choice to choose a moral path through conversations in an RPG. A great profusion of choices, still narrowed down to a binary outcome. We might think of these as Boolean equations.

Other verbs are applicable to a very wide array of situations and choices. “Kill” in an RPG is one such, and because it is a ludic system in its own right, it operates much like an algorithm into which you can feed different values, sort of a finite state machine.

Given a rich enough possible array of outcomes, the player may perceive this actually finite set of possibilities as infinite. At that point, perceptually, it becomes an analog system, not a digital one. And herein lies ambiguity, interpretability, and so on, because in systemic terms, perceived problem complexity is the path towards fun (cf Games Are Math).

For me, the question of what makes systems richly interpretable – as opposed to their dressing in the form of words, art, and music – is an interesting and important one. We have a lot of history and tradition in making words richly interpretable, music richly interpretable, art richly interpretable. It’s not a solved problem, by any means, but it is relatively solved. On the other hand, we don’t have a lot in terms of systems as constructed ludic artifacts.

One way to think of this is on the scale of representational to abstract; a representational artwork imposes more on the viewer. An abstract one invites the viewer to contribute more. Similarly, different choice architectures invite different sorts of contributions from the player. In a linear work, there is lots of room for the reader to interpret what is there; in a non-linear work, there is more room for the player to interpret simply because of what is not there. In game grammar terms (PDF), a game on the lower end of this choice architecture scale might be very deep (chained sequences of choice) but it is not very broad (branching choices).

It is likely axiomatic that structures on the broad end are going to be where richly interpretable systems lie. In other words, where we reach for ludic art.

Learning about color theory, negative space, and line is a key part of art training.

Learning about rhythm divorced from melody, melody divorced from timbre, timbre divorced from harmony is a key part of music training.

Learning about prosody independent of words, plot apart from character, character separate from description, is a big part of learning to write.

The real question is about how we create ambiguity in our work, and it leads to a very personal aesthetic choice: the prickly question of whether a work that accomplishes its effects through ludic systems rather than other media is “better crafted” as a ludic artifact. This says nothing about its merits as a work in totality, but opens up the same sort of question that we ask when we say that a musical has good songs versus relying on its staging and spectacle, that a song has a good melody and a bad arrangement, or whether good acting is carrying a bad script.

In the end, these tools aren’t about which work is brilliant and which is not; it’s about the ways in which they can be brilliant.

April 20, 2013

Thoughts from the LA Games Conference

This past week I was on a panel at the Digital Media Wire LA Games Conference.

The big thing that I wanted to get across to people attending is that many publishers are really caught in a bind. They aren’t willing to take on speculative projects, which is what smaller indies want and need. They ask for vertical slices or even profitable titles before they are willing to sink money into something. But developers are starting to conclude that if they can get a title to that point, they may as well just ship it and make money for themselves. Stuff like the recent financial postmortem of Dustforce shows how many folks are quite willing to trade higher income for creative freedom instead.

With over 50% of developers now describing themselves as independent, and showing a marked preference for platforms with as little publishing friction as possible, we’re going to see a lot of smaller games, a lot of “at bats” for a lots of developers. And odds are greater that some chunk of those will establish a new franchise successfully than a big publisher will. I tossed some guesstimates for team sizes for next gen console development at Chris Early from Ubisoft, and my guess of six studios and 1500 people for a single game was too low for even current gen Assassin’s Creed (he said it took eight studios (!) which is a stunning feat of coordination).

So 1500 people for three years and one game; or half the active industry — let’s say 15000 people — making a game a year in teams of five. That’s a lot of smaller bets. That’s where the next Valves, Rovios, Blizzards will be born. And as predicted, there will be a lot fewer big AAA titles out there than in the past, as their manpower falls and risk aversion continues to rise.

Here’s a few bits of coverage of the conference:

Examiner.com

The only real takeaway that can be gleaned is a new trend of a huge number of low risk forays into the market with the hope that eventually one gets noticed and is hugely successful. As you can imagine, with this type of market saturation, the chances of creating a new brand is increasingly difficult. A better opportunity does seem to lie in what is called mid-core games, which could best be described as similar to last gen console games.

Home Media Magazine

“People who get hooked on casual games are important too,” said Raph Koster, a game designer and author about the gaming industry. He said what the gaming industry needs to realize about people playing Angry Birds is that their platforms for playing are vastly different than in the past.

“It’s important to understand that we’ve been used to thinking of the big three consoles [as our platforms],” he said. [But] Google is a ‘console,’ Facebook is a console.’ They operate as consoles.”

April 16, 2013

Playing with “game”

The world is full of systems. Often they exist below the threshold of what we perceive. It’s all a whirling clockwork of near-infinite complexity, from the tiny mysteries of quantum physics to the wonder of a single tree spanning miles, to the vastness of neurons that sit inside our relatively small skulls.

The world is full of systems. Often they exist below the threshold of what we perceive. It’s all a whirling clockwork of near-infinite complexity, from the tiny mysteries of quantum physics to the wonder of a single tree spanning miles, to the vastness of neurons that sit inside our relatively small skulls.

These systems are dynamic. They move, they change. Had we only the right vantage point, we might be able to see how every gear, every electrical impulse, every vibrating superstring, all can be seen as a filigreed marvel of machinery, the insides of a grandfather clock.

Is everything only this? That’s a question for philosophers and the religious. Many of these systems are of an order of complexity that we may be simply unable to comprehend. Our mental capacity is not so great, after all.

So we arrive at heuristics, our good enough rules of thumb, for addressing these complexities. We can understand physics well enough to plant a robot on a distant planet, but we don’t understand physics. We can understand another person well enough to interact with them, but no one ever really knows anyone fully. We can read a novel — a vast profusion and entanglement of signs, story-worlds, mirror neurons, syllabic scansion, mythmaking, and metaphor — and take away some part of understanding, but likely never all.

Our means of coping with these systems is to simplify. We reduce great complexity down to signs. We classify and categorize and collate. We iconify, cartoon, sketch. When we stop to think about it, we know that all these simplifications are lies. But they are lies we use to live our daily lives, and so we carry on.

Our means of coping with these systems is to simplify. We reduce great complexity down to signs. We classify and categorize and collate. We iconify, cartoon, sketch. When we stop to think about it, we know that all these simplifications are lies. But they are lies we use to live our daily lives, and so we carry on.

We learn to cope with the dangerous, vast, enmeshed gears around us by playing with them. If we stuck our hand into the real gear, it would be mangled and bloody. So we hold back, and either stick our hands into pretend gears (by making a toy model of the system), or stick pretend hands into the real gears (by not emotionally investing in our actions). This is the act of play. Note that the target of one’s play may still be emotionally invested, and so this act is a subjective one.

Bernard Suits called this “a lusory attitude.” His example was golf. The utter ridiculousness of making it harder to drop a ball in a hole — as if there were a reason to do that in the first place! — by requiring you to use a stick to do so… we are creating a system full of complexity for ourselves. A toy system where the rigidity and weight of the stick, the chaotic interference of the swirling wind, the mental impact of the oohs and aahs of the spectators, the way the dew fell across the grass and reflected sun in our eyes, even how to deal with that cramp in our leg from walking all this way — where all these things are present in the toy. Through golf, we learn a little bit about each of these systems, and about the purely made-up system of golf itself. And we carry those lessons on in to our lives, where knowing about glare, about tension, about trajectory and about emotional support, matters a lot.

Bernard Suits called this “a lusory attitude.” His example was golf. The utter ridiculousness of making it harder to drop a ball in a hole — as if there were a reason to do that in the first place! — by requiring you to use a stick to do so… we are creating a system full of complexity for ourselves. A toy system where the rigidity and weight of the stick, the chaotic interference of the swirling wind, the mental impact of the oohs and aahs of the spectators, the way the dew fell across the grass and reflected sun in our eyes, even how to deal with that cramp in our leg from walking all this way — where all these things are present in the toy. Through golf, we learn a little bit about each of these systems, and about the purely made-up system of golf itself. And we carry those lessons on in to our lives, where knowing about glare, about tension, about trajectory and about emotional support, matters a lot.

We are wired to; our brains need these icons, simplifications, because otherwise we cannot cope. So we give ourselves subtle encouragement to keep trying to figure out the machinery of everything. We drop dopamine for curiosity and reward, and we increase our focus when tackling new things. It’s hard, and we don’t do that much, honestly. When we do, we think of it as fun.

There are systems we — not master, but cope well enough with. They become trivial, routine. And there are systems we stare at bewildered, because there is no handle on them, no starting point. They are noise to us. And this is different for every one of us, as we build on what we know.

And for everything else in the middle, we can choose to approach it with a lusory attitude, thereby turning it into a game.

We move through these. They are consumed. As a child, Snakes and Ladders is one such. Then it falls off the bottom as trivial. Did it cease being a game? For that person, yes. They engage with a system, there is a process, and the process ends, and it stops being a process. And with it, the game is over.

We do not all approach the same thing in the same way. For another person, a given system may never be approached with this attitude of learning. For them, the lusory attitude never starts. What that system a game? For that person, it never was.

And when someone presents a system for an audience’s consideration, they may present it as a game, or as a novel, or as something else entirely. If someone creates a hypertext work that some call a game, and the author objects, does it it mean it never was a game? To that author, yes.

We cannot, therefore, ever say what a game is in this sense, because it is different for everyone. To one, the stock market is a game. To another, reading Harry Potter. To another, a piece of interactive fiction, and to another, a game of chess. We play a sport, an instrument, a game, a joke, a part. The language is wise in this way, it sees underlying truths.

We cannot, therefore, ever say what a game is in this sense, because it is different for everyone. To one, the stock market is a game. To another, reading Harry Potter. To another, a piece of interactive fiction, and to another, a game of chess. We play a sport, an instrument, a game, a joke, a part. The language is wise in this way, it sees underlying truths.

So the rhetorical move is to make the word “game” reside at heart in the process, not the object. Game is a big tent, and a “player” can shove absolutely anything in there.

Creators should also therefore keep in mind that every audience member can also yank something out. There is no mileage is getting upset about it.

But this does not mean that everything dissolves into a soup of subjectivity. The systems are real, and they have characteristics.

The primary characteristic of systems that are commonly approached with a lusory attitude, by those who are not differently abled in some way, is that they fall inside a typical range of complexity. Complexity almost in the formal mathematical sense. When solved, they cease being approached as a game, and things below a complexity threshold tend to get solved.

Some people associate “play” with freedom, flexibility, lack of rules. But it is perhaps better to think of “unstructured play” as actually being about many rules, tons and tons of them, many unstated, often changing on the fly; and “structured play” as being about fewer rules, clearly stated. Calvinball is unstructured; Nomic, funny enough, is highly structured. Both are fertile fields for play.

There seem to be four big classes of things that meet these criteria, triggering different sorts of fun. We can say this because it has been measured in the expressions in our faces and analyzed: hard fun, easy fun, social fun, visceral fun.

One is our selves. Our self is a sack of fluid primarily made up of colonies of distinct organisms that cooperate enough most of the time that we can move through the universe as if we were a coherent entity, despite the fact that we colonize and are colonized every moment, a turnover of life that means that we are more a city than a citizen. Our self is a car that we drive, that we expect to respond, that we sense through electrical impulses traveling at speeds measurable by engineering. Our self is an array of systems, and we can approach interactions with it as a literally visceral game.

One is our selves. Our self is a sack of fluid primarily made up of colonies of distinct organisms that cooperate enough most of the time that we can move through the universe as if we were a coherent entity, despite the fact that we colonize and are colonized every moment, a turnover of life that means that we are more a city than a citizen. Our self is a car that we drive, that we expect to respond, that we sense through electrical impulses traveling at speeds measurable by engineering. Our self is an array of systems, and we can approach interactions with it as a literally visceral game.

A

nother is also our selves. Each self is a soul wandering a space of poetry, attaching and detaching meaning from moment to moment. Our self is the composite of the other people in our lives, half reflection of neurons firing in tandem as we feel the same emotions others do, triggered by a cocked eyebrow or a fleeting micro-expression of a smile. This self sees and seeks beauty, small surprises. It feels pride in mentorship, and petty joy when it sees another trip. It catches delight in photographs and shares them with nostalgia. It is not so much that we can play a game with our own emotions and thoughts, as it is that the unbridgeable gap between selves is a system of great complexity. Here is where so much personal art resides. Is it no accident that a portrayal of humans interacting is called “a play.” Understanding each other is itself a powerfully social game.

nother is also our selves. Each self is a soul wandering a space of poetry, attaching and detaching meaning from moment to moment. Our self is the composite of the other people in our lives, half reflection of neurons firing in tandem as we feel the same emotions others do, triggered by a cocked eyebrow or a fleeting micro-expression of a smile. This self sees and seeks beauty, small surprises. It feels pride in mentorship, and petty joy when it sees another trip. It catches delight in photographs and shares them with nostalgia. It is not so much that we can play a game with our own emotions and thoughts, as it is that the unbridgeable gap between selves is a system of great complexity. Here is where so much personal art resides. Is it no accident that a portrayal of humans interacting is called “a play.” Understanding each other is itself a powerfully social game.

The third rough category (and these are not clear cut boundaries, no indeed!) is that of the things which are not us and have no mind. The branching decision trees, the state machines, the patterns of animal migration and the formulae of physics. Many see this as a cold and inhospitable world, and in aggregate, it is. But such is the world we live in. Long ago we learned we had to master systems like the rhythms of seasons and the arc of the spear. These all reduce to mathematics, a hard-edged glittering quantification that conveniently categorizes itself into levels of complexity. Here we find that the systems that tease us with their apparent comprehensibility are ones that fit inside a certain level of computability, ones that we can use our remarkable brains to address with interim solutions called heuristics, but cannot ever quite solve. As we mature in our knowledge, we learn that more things are computable than we thought, and they slide down the scale. Sometimes we never master the heuristic, and the triviality of a system like Sudoku never becomes apparent. In casual lingo, people term the trivial ones puzzles usually, glossing over the fact that a formal classification of NP-hard or PSPACE-complete doesn’t mean that a given player sees the problem in that category. These things are hard, and we often privilege this level and call it “real games.” But that does a disservice to what is perhaps better termed a formal game.

The third rough category (and these are not clear cut boundaries, no indeed!) is that of the things which are not us and have no mind. The branching decision trees, the state machines, the patterns of animal migration and the formulae of physics. Many see this as a cold and inhospitable world, and in aggregate, it is. But such is the world we live in. Long ago we learned we had to master systems like the rhythms of seasons and the arc of the spear. These all reduce to mathematics, a hard-edged glittering quantification that conveniently categorizes itself into levels of complexity. Here we find that the systems that tease us with their apparent comprehensibility are ones that fit inside a certain level of computability, ones that we can use our remarkable brains to address with interim solutions called heuristics, but cannot ever quite solve. As we mature in our knowledge, we learn that more things are computable than we thought, and they slide down the scale. Sometimes we never master the heuristic, and the triviality of a system like Sudoku never becomes apparent. In casual lingo, people term the trivial ones puzzles usually, glossing over the fact that a formal classification of NP-hard or PSPACE-complete doesn’t mean that a given player sees the problem in that category. These things are hard, and we often privilege this level and call it “real games.” But that does a disservice to what is perhaps better termed a formal game.

The last category, alas, is a degenerate one. It is the dark side of the math. We are lousy at estimating probability. We think we can estimate, but we cannot. We think we grasp big numbers, but we don’t. We make projections, and we are wrong. Reality is exponential, stochastic, chaotic, and we see a pattern only to have it be a false image. This, alas, is exploited by the less scrupulous. But nonetheless, there is a lot of fun in these unsolvable game of gambling.

The last category, alas, is a degenerate one. It is the dark side of the math. We are lousy at estimating probability. We think we can estimate, but we cannot. We think we grasp big numbers, but we don’t. We make projections, and we are wrong. Reality is exponential, stochastic, chaotic, and we see a pattern only to have it be a false image. This, alas, is exploited by the less scrupulous. But nonetheless, there is a lot of fun in these unsolvable game of gambling.

It may seem like this is reductionist. It is. These are no categories, however, but qualia. The experience of each is subjective. In fact, a system may be approached in a way that is non-lusory, in which case we may use it for meditation, for practice, for comfort, for narrative purposes (though this last one is sneaky and may lure you back into a lusory attitude!).

It may also seem that what is happening here is that we are destroying any possibility of formalism. But that is not the case.

Some systems are artifacts. They are not necessarily physical (in fact, quite often, not physical), but they are designed. We can leave aside the question of whether physics, the weather, and the human mind are of this type, and look at the stock market, tennis, chess, and Pong. Some of these partake to a greater or lesser degree of the folk process; some of these have had a more emergent history than others; and yet they are all artificial constructs of rules.

Some systems provide affordances for being treated with a lusory attitude. We play the stock market, we play a musical instrument. These artifacts were not created with the intent of their being used with a lusory atttude, but there is a degree of simpatico.

Some systems provide affordances for being treated with a lusory attitude. We play the stock market, we play a musical instrument. These artifacts were not created with the intent of their being used with a lusory atttude, but there is a degree of simpatico.

Some provide not just the affordances but suggestions, prodding you towards methods of engagement. We play with a ball, we play with SimCity or Minecraft‘s sandbox mode, we play with our understanding of a book. We impose our own goals on these, but we were guided to them. In common usage, this is often called a toy but as you can see from the examples, not always.

Some provide not just the affordances but suggestions, prodding you towards methods of engagement. We play with a ball, we play with SimCity or Minecraft‘s sandbox mode, we play with our understanding of a book. We impose our own goals on these, but we were guided to them. In common usage, this is often called a toy but as you can see from the examples, not always.

Some provide a goal. We play Halo, we play soccer, we play backgammon. Common language calls this a game, but as we have already seen, common language has overloaded that word a lot. We could perhaps term this an intentionally designed ludic artifact. In the past, we have called the process of consciously creating a ludic artifact to be “game design” or even “game systems design” but that nomenclature is failing us.

Some provide a goal. We play Halo, we play soccer, we play backgammon. Common language calls this a game, but as we have already seen, common language has overloaded that word a lot. We could perhaps term this an intentionally designed ludic artifact. In the past, we have called the process of consciously creating a ludic artifact to be “game design” or even “game systems design” but that nomenclature is failing us.

The commonality here lies in the process (also called “playing a game,” argh) that is superimposed upon these artifacts or situations. And this process has a grammar to it. Let us for the moment term this a ludic pattern.

Some critical frameworks have been interested in ludic patterns (game formalism, game grammar, ludology), and others in the process (game narratology, reader response theory), but I would contend that this is a false dichotomy, because the process often starts with an interlocutor taking a systemic artifact, whether it was intentionally designed as ludic or not, and imposing their ludic pattern upon it. Often, they simply take the suggestions the artifact affords, or explicitly follow the goals that the artifact proposes. They do not always submit, though; the invention of new goals (speed runs, griefing, playing misere) is extraordinarily common. In fact, one of the commonest (and amply represented by the entire quale of social play) is mere understanding.

When the ludic artifact is highly structured, the ludic pattern is like a ghostly echo of it: the process much resembles the artifact. When it is loosely structured or self-imposed, the pattern still looks like a ludic artifact, but not because the artifact shaped it strongly. It partakes of the ludic shape because that is one way we as humans learn. Not the only way: one (big) way.

When the ludic artifact is highly structured, the ludic pattern is like a ghostly echo of it: the process much resembles the artifact. When it is loosely structured or self-imposed, the pattern still looks like a ludic artifact, but not because the artifact shaped it strongly. It partakes of the ludic shape because that is one way we as humans learn. Not the only way: one (big) way.

To illustrate the way in which the word game trips us up, this can be described as

“This is a game because I treat it as such”

because it ironically implies an act of subjective transformation:

“This artifact (which may be self-described as a “game”/”work of IF”/”art piece”/whatever) is a game (colloquial umbrella for any system that affords “play”) because I treat it as a game (superimpose a ludic pattern on it).”

So where is the scope for formalism? Completely intact. It simply operates as one critical lens among many, focusing primarily on the structural qualities of the ludic pattern and most especially ludic artifacts. It is simply a way of treating the ludic learning process itself as a system to figure out. And that, to formalists, is a pretty fun game: they’ve made great progress in finding out the grammar to this system — enough, at this point, to be able to argue with Wittgenstein. Formal analysis is just one more reader response, one more way to play. Even this little essay is nothing more than that: a personal response to a baffling system.

So where is the scope for formalism? Completely intact. It simply operates as one critical lens among many, focusing primarily on the structural qualities of the ludic pattern and most especially ludic artifacts. It is simply a way of treating the ludic learning process itself as a system to figure out. And that, to formalists, is a pretty fun game: they’ve made great progress in finding out the grammar to this system — enough, at this point, to be able to argue with Wittgenstein. Formal analysis is just one more reader response, one more way to play. Even this little essay is nothing more than that: a personal response to a baffling system.

Does this mean that at bottom it’s all formal? No, that’s not true either. Every engagement is subjective. We can run domain analysis over and over, but get ourselves into trouble every time we shift contexts.

So: anyone can make a game. In fact, everyone does, every time they play “a game” whether it’s a “game” or not. So, go make games, Games, games, GAMES! And let’s all have the understanding that we are all at play here, and it should be fun, even when play is deadly serious.

April 12, 2013

Every genre is only one game

Well, sort of. I really mean “systemic game” and I am really talking only about game systems here.

So let me preface this by saying that this article’s title is hyperbolic exaggeration. It uses the term “game” in my annoyingly formal, reductionist way. But I want to say it anyway, for the sake of the provocation; framing it this way jars some preconceived notions about terms out of my head. (At some point, I’ll do a post here about finding alternate, less loaded terms. But for now, since I want to get this out, I’m running with it.)

If you take as given that a game can be analyzed in terms of its grammatical structure — the verbs, nouns, adjectives that make it up – then it leads to the natural thought that you might get the same structure with minor variations.

This is a rose.

This is a blue rose.

This is a red rose with whitish leaves.

This is a thorny rose with a strong aroma.

A rose by any other name would smell as sweet; a rose is a rose is a rose.

And an FPS is an FPS is an FPS.

(Is this reductionist? Absolutely. It discounts all the things that sit on top of the same skeleton and make them radically different player experiences. But bear with me a moment).

In a game grammar sense, the verbs are the actions the player can take: smell, pluck petals, etc. The nouns are the objects that exist with the system: the petals, the pistils, the stem, the thorns. The rules arise out of the range of possible verbs and the reactions the rose may present to your action. And the “content” – well, that is the statistical variation between roses.

Now consider the small game of RPG combat. The verbs are the actions the player can take: kick, stun, nuke, etc. The nouns are the objects that exist within the system: the sword, the armor, the loot, the orc. The rules arise out of the range of possible verbs and the reactions the orc may present to your action. And the “content” – well, that is the statistical variation between orcs.

But content does not generally affect the rules. It is the x in f(x). The algorithm remains the same, even though the experience may differ radically. We use adjectives – sorry, content – sorry, statistical variation – in order to ring changes on the “machine” that lies underneath.

This means that you can find isomorphism between games. We often identify these as systems held in common, or as “design patterns.”

But often, we can look at a whole constellation of games and say “these have a significant degree of isomorphism.” In some cases, the differences lie entirely in the content. In other cases, they lie in rule variations that are on the face of them minor. We can usually spot these because we call them “a variant.” Poker variants, for example, share 80-90% of their graph, and the often significant differences in dynamics arise because of fairly minor rule changes.

If we choose, we can even look at many of these rule changes as actually being statistical variations. For example, there is a difference in perspective that comes from saying that the number of publicly shared cards in vanilla 5 card poker is a scalar variable that happens to be set to zero. To a player who only knows vanilla poker, the addition of face up cards seems like a new rule, when in fact it’s just like showing that sometimes monsters can group in an RPG, or that gravity can change, when you have thought that in practice gravity was inalterable, or grouping did not exist.

That isn’t really an honest way of looking at it – when a Texas Hold ‘Em is developed, it’s likely that no one approached it as “let’s increment this zeroed out variable to a positive number.” But in analytical retrospect, the addition of a new statistical field could almost be thought of as retroactive to all earlier versions of Poker. And thus poker’s base definition grows to encompass “a game where there might be publicly shared cards.”

As genres develop, they complexify for a number of reasons. Players master the dynamics of the previous system, according to their ability and inclination. Players who have reached mastery demand the same system but with greater variations or better balance, and the response of designers is to add new rules. Special cases arise, like the offsides rule in soccer. Eventually, the ruleset grows rococo, the number of variables extreme, and the accessibility of the genre suffers. A given variant happens to sit at the sweet spot of complexity and accessibility, and becomes the “genre king,” to use Dan Cook’s term. In poker, that was Texas Hold ‘Em.

Then the genre often dies as it spirals off into increasingly rococo variants for an increasingly elite hobbyist audience.

There is a very real craft difference between

Merely providing statistical changes to a ruleset. This is level design, it’s making new monsters, it’s adding twelve new guns or five classes.

Providing a whole new statistic that effectively creates a new rule, and thus a host of new mechanics. (Technically, I’d probably only call it a new rule if there’s a new verb to go with it; otherwise, it’s just a new statistic).

Providing new rules and mechanics altogether, that connect to the existing structure: new verbs and nouns.

Providing a completely new system of rules: verbs, nouns, everything.

This may seem like pure intellectual wonkery, but it’s not. It’s actually a great aid in thinking about new gameplay, new markets, derivative work, and ambition and innovation, and one of my preferred things to point at when thinking of what game grammar can do in a concrete sense.

From a purely practical point of view, these four tiers serve the following market purposes:

Providing level packs, more of the same experiences, ongoing support to a fan base for a game genre.

Adding a minor variant to the game. Likely to retain users into the genre for a longer amount of time, but moving it further down the road to over-complexity.

Adding a major variant that many will consider a new game altogether, because the variant is extreme enough to create a very different experience: capture the flag versus deathmatch.

Invention of an actual new game, a new genre. In the long run, may well lead to enormous new markets… just be aware that in practice, this is the hardest thing to do, and also you as the inventor likely won’t be the one who capitalizes the most on it. It’s deeply unlikely to jump right to the genre king, though we have seen it happen (Will Wright seems to have a knack for it).

From a craft point of view, these also fall nicely into system design difficulty tiers. It is harder to do #4 than #1.

Right now, I increasingly see the major variant move, which is exciting. The way in which dimensionality was established as a new platformer variable, for example, has opened up a new fertility in that genre. And this is precisely a formalist sort of move, driving innovation. Identify a variable, see how it can be integrated into an existing superstructure, reap an IGF nomination and some really cool new gameplay.

Ah, but remember I said bear with me regarding the annoyingly reductionist nature of this? You don’t need to approach things from the formalist, mathy end. One of the easiest ways to tackle the hardest task, that of inventing a new genre, is to start with a new experience, one never represented in a game before, and attempt to construct the model for it. The game that makes you feel like a tree, the game about the death of your child, the game about theoretical debates… in other words, to me this points one way towards developing new experiences.

Sometimes, you’ll end up with something that turns out isomorphically identical to an existing game. The FPS becomes the photography game. You may have failed at inventing truly new gameplay, but you have still opened new audiences, reached new expressive potential. (In fact, how come nobody has gone back to photography games and tackled stuff like focus, depth of field, exposure time, and so on? Missed opportunity!)

The biggest thing I think this tool reveals, though, is how incredibly rare it is for new “games” to be invented. As soon as we say that really, there has only been one FPS and variants, one platformer and variants, what a change in perspective!

To me it conjures up vistas of the millions of systems and models we have yet to discover, and the amazing future that awaits us in game design.

April 9, 2013

A Letter to Leigh

when people say games need objectives in order to be ‘games’, i wonder why ‘better understanding another human’ isn’t a valid ‘objective’

games need ‘challenges’ and ‘rules’, isn’t ‘empathy’ a challenge, aren’t preconceptions of normativity a ‘rule’

- Leigh Alexander writing on Twitter

Dear Leigh,

I have such a complicated emotional response to this. And I think you like getting letters, based on what I see on the Internet.

I would rate better understanding of another human and the challenge of empathy as bare minimum requirements for something reaching for art.

The assumptions underlying this question are the interesting thing. A game of bridge demands great understanding of another human, and great synchrony of thought. A huge number of the games of childhood are designed to teach empathy. We play games all the time in order to get to know people.

But that’s not what you really mean, is it. What you are really talking about is something else entirely.

The debates over “what is a game” have been going on for a long time now. They have an uncomfortably personal edge lately. We are seeing powerful works of art created in the digital medium. Further, they are deeply personal statements. And even further, many of these works are coming from groups that have been marginalized, oppressed, discriminated against.

Many of these works are brilliant.

The assumption implicit in what you’re saying is that a work’s formal structure isn’t as relevant as what it accomplishes. This is a completely valid point of view, but not, I think, all that useful for sorting something into a genre. But I accept that many simply don’t care about sorting that way.

But it also sort of implies that games with objectives and rules haven’t been reaching for these goals too. And that’s not only not true, but unjust to games’ expressive power.

What is reveals is a preference for the kinds of understanding you want, towards specific modes of conveying that understanding.

An aesthetic of unplayability

I have been fascinated lately by the fact that many art games accomplish their power and effect by subverting “gameness.” And what I mean by that is denying the player agency.

When we think about what makes a game, we almost always come back to some degree to interactivity. I’ve argued in the past that interactivity is hardly unique to games, and therefore can’t be used as the sole yardstick. But I sure wouldn’t try to classify something as a game that is non-interactive.

Historically, many signature emotional moments in game have been accomplished by using non-interactivity. When Floyd dies in Planetfall, we do not have control. People still rhapsodize over the death of Aeris in Final Fantasy VII. We did not have control.

More recently, I have seen the following currents develop:

The game which “lies” to you about a winnable situation to accomplish its effect. Freedom Bridge is one such example. It does not meet the formal definition of “game.” You can’t beat it. You can’t even make progress. There is only one pattern to perceive: futility. In a different way, the painfully honest That Dragon, Cancer (which I haven’t played) is apparently also accomplishing its effect through helplessness.

The game which uses the fact of engaging with it at all to accomplish its effect. These games have complicity as their means of making a point. Brenda Romero’s Train is one such: a game whose only moral move is not to play, but of course stating the mechanic baldly reminds one of the line from the film Wargames. September 12th is another.

The game which uses the form of gameness but which pulls off its emotional impacts through moments of presenting false choices. At GDC I was treated to a lengthy description of To The Moon , which sounded like it fit this definition (and which I need to go track down and play), and it’s interesting to read the review on IGN as the reviewer attempts to explain why it’s a great experience while not being “gamey.”. This is also the signature move in Porpentine’s Twine games such as Howling Dogs or How to Speak Atlantean , where we find ourselves taking actions as rote, finding the same hyperlink twenty times on a page, all with the same effect.

I think all of these games are awesome, and am humbled by them. But I also wonder about the overall aesthetic. I would pose the following questions to their creators:

Does choosing non-interactivity as the central defining characteristic effectively put you in a broadcasting position, and therefore turn the games into monologue rather than dialogue?

What does that mean for creators who outright state they are seeking to create empathy? Is dialogue not actually the best way to create empathy? If so, what are its weaknesses? Or is it that we cannot truly yet accomplish dialogue yet through our medium?

Does choosing to deny players agency mean that you are in effect giving up on whether game rules can accomplish your goals?

In effect, are all of these games subverting games themselves? Is it conscious? To what degree is the insistence that these are in fact games reflective of an ambivalent relationship to games?

I end up with these questions because these by and large feel like narrative moves, not game-like moves. Or perhaps, they feel game-like in the sense that I the player feel like I am being played, in the “are you playing games with me?” sense. They feel, in the end, like the twist ending, the O Henry moment, like it was all a dream. Like the ending of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, or John Cage’s 4’33”, something that should probably only be done once, marveled at, and then moved past.

The impositional narrative

Don’t get me wrong – something like the power of daily ritual, as displayed in Howling Dogs or Cart Life, is something that only this medium could do. The moment when you are a Tetris piece that does not fit, in Dys4ia, is something only our medium could do. I am not making an aesthetic judgement here about these tools; I am posing a craft question. I want to believe that despite the political layers that adhere to the discussion of this topic, that we are all craftspeople who care about the carpentry of what we do. We all need to reach our own accommodations and understand our own aesthetics.

Games have had an element of futility for a long time. Single-player games especially. The robots always won, in Robotron. The Space Invaders always conquered the earth. But at least we were able to make a go of it. The games themselves have different messages, but the aesthetic here says that we can’t make a go of it. It’s a rigged world. You can’t do better at Train. You can only do worse. The message of September 12 is “don’t play me.”

It’s probably me seeing things, but I can’t help but wonder to what degree the overall aesthetic in the art game community is a descendant of (bear with me) Super Mario. If there’s one overriding factor in the aesthetic of a Nintendo game, it’s control. Miyamoto is said to plan absolutely everything. Every outcome. Every permutation. Every possibility.

In this, the underlying fundamental kinship of the big AAA game and the arthouse darling Twine game is apparent. They are both more about the author than the player.

Are they games?

Can we, should we, do I, exclude these things from the realm of games? Not only do I not exclude them, I welcome and evangelize them and have been doing so for over a decade (despite what some say about me). But I actually think it’s the wrong question on many levels.

I wonder instead whether the work is trying to exclude itself from “gameyness.” By and large, these are games about people who lack power and lack control. The message gets across because games have always been about agency; gamers are used to having power and control, and to have the game itself deny it is a wake up slap across the face.

Effectively, these are games as rhetoric not games as dialectic, moving against the fundamental current of gameness. And the rhetorical move is “destroy everything,” as Porpentine put it in her GDC13 session with Terry Cavanaugh on indie games.

Overall, to me it feels like it speaks to a conflicted relationship with games. The creators of these works do not want to be excluded: it is their medium. At the same time, the aesthetic argues for un-gaming things.

Nor do I mean to pick on indies here; Warren Spector made a statement in his session about how “story is finally getting taken seriously” that was a moment of great cognitive dissonance for me. To me, it feels like story is all that gets taken seriously in AAA, certainly, and to a large degree in the art game and indie movements. And in AAA we have seen some moves lately that speak to a conflicted relationship there as well: No Russians using exactly the same rhetorical devices as the art games, Spec Ops: The Line, the arguably failed narrative line in Far Cry 3, even the discussions over violence in Bioshock Infinite.

Games are uncomfortable with themselves, and not just on the level of “what are our narratives.” But actually on the level of “what are games for?” We see our tools taken up by crass moves into marketing and monetization, we see the craft we developed being used for manipulation, and we start asking ourselves whether everything we do is manipulation, whether we are fundamentally crass.

I find myself cheering on the punk neon fringe. But I also find myself saying “please don’t destroy everything” because some people live in there, and it is always worth getting to know people, especially the ones not like you.

Ranting is not conversation

I was hesitant to write a lot of this down, because while many found this year’s GDC to be the most inclusive ever, I also was struck by the degree to which GDC time was spent not with “the good guys winning” but rather with good guys fighting good guys. I found myself cast as an excluder because I am interested in definitions, and I am sure this article will land me there again. (In fact, the height of cognitive dissonance was having a lovely conversation about design with Cara Ellison at a late night party – about many of these same topics, in fact; and finding myself sort-of-namechecked the next day when Anna Anthropy read a modified version of Cara’s poem “Romero’s Wives” aloud — a version filled with righteous anger that is impossible to quarrel with). I literally had one indie developer whose work I admire run away from me in the street.

On the political level, every word is charged. On the theoretical level, the pomo stream of thought says there are no boundaries. But in both cases, we see these tools turned again and again towards reinforcing labels, asserting identities. A monologue is implicitly reinforcing boundaries, just like defining a term is. None of what I have written in this little essay is about the messages in the works or about the games’ creators. But I fear it will be taken that way anyhow, just as my earlier writings on narrative and mechanics were taken. I find myself wanting to say sorry sorry sorry for — having an academic debate about minutiae of the structure of interaction?

But then we get something like the Experimental Gameplay Workshop, where everything we saw was actually about mechanics. Including mechanics that work to create empathy in profoundly non-narrative ways: Spaceteam, Searchlight, Ninja Shadow Warrior. I found it deeply inspiring in a way that the prevailing narrative of the conference was not quite. But I also recognize that I took away little understanding of people and a lot of understanding of math from most of the games presented, being as they were “about geometry” rather than “about empathy.”

All in all, I wonder whether fundamentally we as a community are doing a bit too much ranting. In the games and in the aesthetic and yes, from stage at GDC. Oh, I don’t mean in the literal sense of strident complaint. I mean in the metaphorical sense of holding forth. Games have had nothing to say for so long that I worry that we have collectively concluded that “saying something personal” is what makes them worthwhile art.