Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 44

December 21, 2015

When Character Was King

It’s been years since I read Peggy Noonan’s beautiful biography of Ronald Reagan, When Character Was King (Viking, 2001), but I’ve been thinking a lot about that title. If conservatives in this country want to claim the mantle of Ronald Reagan, or simply want to be true to conservative principles, they will not overlook the question of character when choosing a president (or a nominee, as the case may be). Of course, being an admirable human being does not by itself make one a good president. Character is not a sufficient condition for being a great leader, but it is, I believe, a necessary condition.

It’s been years since I read Peggy Noonan’s beautiful biography of Ronald Reagan, When Character Was King (Viking, 2001), but I’ve been thinking a lot about that title. If conservatives in this country want to claim the mantle of Ronald Reagan, or simply want to be true to conservative principles, they will not overlook the question of character when choosing a president (or a nominee, as the case may be). Of course, being an admirable human being does not by itself make one a good president. Character is not a sufficient condition for being a great leader, but it is, I believe, a necessary condition.

No doubt, every politician in our day (or any day?) is bound to over-promise, overestimate his (or her) own importance, and come across a wee bit weasel-y from time to time. But that doesn’t mean we have to settle for the lowest common denominator of personal integrity. Just because Jesus isn’t running for president, doesn’t mean we might as well vote for Barabbas.

We are whole people, with private lives and public lives that cannot help but bleed one into the other. Among other considerations, Christians should insist that wherever possible–and evangelicals will play a big role in choosing the Republican nominee–that their political leaders are men and women with a track record of honesty, self-control, self-sacrifice, fidelity, wisdom, prudence, courage, and humility.

Along those lines, I’m struck by this passage at the end of Noonan’s book:

I asked him [Reagan] how he viewed his leadership. He replied, “I never thought of myself as a great man, just a man commited [sic] to great ideas. I’ve always believed that individuals should take priority over the state. History has taught me that this is what sets America apart–not to remake the world in our image, but to inspire people everywhere with a sense of their own boundless possibilities. There’s no question I am an idealist, which is another way of saying I’m an American.” (317)

“I never thought of myself as a great man.” The first shall be last, and the last shall be first. I think that’s how an even more famous man once put it. Two paragraphs later, Noonan expanded on an overlooked aspect of Reagan’s humility.

He added that he had gotten through his presidency only with the help of prayer. “I’ve prayed a lot throughout my life. Abraham Lincoln once said that he could never have fulfilled his duties as president for even fifteen minutes without God’s help. I felt the same way.” (317)

Better historians than me can argue about the personal faith of Reagan and Lincoln, but few (especially those who will vote in Republican primaries) will doubt that they were good men and great presidents. I’m sure their successes can be attributed to many things: hard work, common sense, strong convictions, and a little bit of luck (or happy providences, if you will). But surely they would not have been able to accomplish all they did, with such enduring admiration, if their lives were marked by self-aggrandizement, personal meanness, and wild inconsistency.

Is there one candidate Christians must vote for? No. But are there Christian graces, or at least common grace virtues, that we should pray for and look for in our leaders? Absolutely. Don’t ask “who would I like to have a beer with?” or “who sticks it to the people I’m most fed up with?” Ask: “Who would I trust to put the interests of others above his own? Who has the wisdom, the discernment, and the honesty to make the right decisions when no one is looking?” That’s not all that’s needed in a president. But it’s a start.

When it comes to doing good in this world, no amount of charisma can overcome a dearth of character. In the short term, perhaps. But in the long run: people do as people are. Character is king.

December 20, 2015

Monday Morning Music

December 16, 2015

Sweet Little Jesus Boy

The following is a Christmas sermon I preached a couple years ago. I thought it might be worth posting again as Christmas approaches.

The following is a Christmas sermon I preached a couple years ago. I thought it might be worth posting again as Christmas approaches.

One of the Christmas traditions in my church growing up was that every year during the Christmas Eve service this one particular gentlemen would sing Sweet Little Jesus Boy. He was the right church member to sing the song. He was an old African American gospel singer, and he could sing it well. And even though it was a different style of music than all the other songs we would sing on Christmas Eve, it became a favorite of our almost entirely white congregation.

Sweet little Jesus Boy,

they made you be born in a manger.

Sweet little Holy Child,

didn’t know who You was.

Didn’t know you come to save us, Lord;

to take our sins away.

Our eyes was blind, we couldn’t see,

we didn’t know who You was.

The song was written in 1934 by Robert MacGimsey (1898-1979), a white man from Louisiana who made it his life’s work to learn, preserve, transcribe, and make accessible African American folk music from the South. MacGimsey wanted Sweet Little Jesus Boy to echo the sentiments of black Christians in the Civil War era. He once described his most famous song as more a meaning than a song: he pictured an aging black man whose life had been full of injustice “standing off in the middle of a field just giving his heart to Jesus in the stillness.”

The connection between our sufferings and Christ’s sufferings is powerful.

The world treat You mean, Lord;

treat me mean, too.

But that’s how things is down here,

we didn’t know t’was You.

And the refrain at the end of several of the verses has a haunting simplicity to it: “We didn’t who you was.”

Just seem like we can’t do right,

look how we treated You.

But please, sir, forgive us Lord,

we didn’t know ’twas You.

Sweet little Jesus Boy,

born long time ago.

Sweet little Holy Child,

and we didn’t know who You was.

Do you know who Jesus was?

Isaiah 9 hails the Messiah as the light of the world in a land of deep darkness. He is the child born under the oppression and eventual execution of the Roman government. He is our Wonderful Counselor and the Mighty God. He reveals to us the Everlasting Father. He is the Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his kingdom and peace there will be no end. He will rule with justice and righteousness from this time forth and forevermore.

So who was this child born of Mary?

A good teacher perhaps? That’s a popular answer: Jesus was really a humble prophet, a teacher of peace and justice. But some of his followers made up all these things about him–they invented the miracles and the exalted language about himself and the resurrection. Maybe the Christ of faith is completely different from the Jesus of history. Perhaps, but consider two major problems with this theory.

First, the only Jesus we have is the Jesus of faith. Virtually everything we know about Jesus is given to us through the eyes and pens of those who believed in him. So any attempt to find the historical Jesus behind the Jesus of faith is an attempt to find what we would like Jesus to be and not an attempt based on history. The only history we have about him comes from those who were changed by him. So either we are going to have to accept what Jesus’ followers said about him or admit that we can’t really know anything about this man.

The second problem with taking Jesus as simply a good moral teacher is that the people who argue for this approach almost never take into account all of Jesus’ teachings. What they mean is not so much that they respect Jesus as a teacher, but that Jesus was smart enough to say some of the same things they would say. So people appreciate Jesus the good teacher when he talks about turning the other cheek or walking the extra mile or giving to the needy. But they ignore all the parables Jesus told about weeping and gnashing of teeth and being cast into outer darkness. They love the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount, except they breeze past the places where Jesus says those who refuse to forgive will be punished, and those controlled by lust will be thrown into hell, and divorce except on the grounds of sexual immorality is wrong, and everyone who doesn’t build his house on Jesus is a fool. We gravitate to the peace on earth, good will toward men, and overlook the times when Jesus says his coming would bring division on the earth and turn mother against daughter, brother against brother, and father against son. No one should hail Jesus as a great moral teacher until he reads through all that Jesus taught. Then you can decide if still think he was a good teacher.

So who was the baby the Magi came to worship?

How would you answer that question? As I see it, there are two consistent answers and two inconsistent answers.

The first inconsistent response is to take part of Jesus: “I’ll take the teachings I like and ditch the rest. I’ll take his good deeds but not his hard words. I’ll take his love for humanity and not his desire to glorify himself.” Now, don’t get me wrong, you can pick and choose what you like about Jesus. People do it all the time, but it’s inconsistent. Don’t say you follow Jesus or even that you think he’s a great teacher. Be honest enough to say “I like the ‘judge not’ line, the love your enemies bit, and the cup of cold water thing, and that’s about it. Other than that, Jesus was a quack and not really very nice.” To say anything else is inconsistent.

The second inconsistent response is to accept that Jesus is the Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace, and accept that he is the perfect Son of God, the King of the nations, the Righteous Judge, and the hope of the world, and then live like it doesn’t matter. If you thought I was God–and I don’t think I need to assure you I’m not–you would be very interested in what I thought, and how I wanted you to live, and what I was like. You would talk to me and worship me and tell others about my true identity. And if you did none of those things, it would be right to question whether you really thought I was God. Faith is more than intellectual assent to certain doctrines, it is an entire life based on the conviction that these doctrines are true.

So who is the babe in the straw?

The first consistent response is to say, “He’s a nobody. He didn’t even exist. Or if he did exist, we can’t know anything about him. The gospels are myths and legends with no grounding in history. I may like the victory from defeat theme in the gospels, but I don’t need Jesus for that. I don’t really care who this Jesus is and neither should you. The billions of Christians singing to Jesus this week are worshiping a figment of their imagination.” That would be consistent.

And the other consistent response is to believe the Jesus is the Son of God, to worship him, and obey: “Yes, Jesus you are the image of the invisible God. You are the sacrifice for our sins. You are the only way to the Father. You are the resurrection and the life. You are the once and coming King.”

I can’t persuade you to say that for yourself. I can try to show you that it is not unreasonable, and is in fact, plausible, but if you don’t want to believe, you will find a reason not to believe. Just try to be consistent. My prayer is (1) that those who accept all these things as true will live and die as if they were, and (2) that those who don’t yet accept these things will ask God to help them understand if these things are so. Because wouldn’t it be terrible to meet Jesus on that great getting up morning, look him in the eye and then look at each other and confess, “We didn’t know who you was.”

December 15, 2015

Internship Program at URC

University Reformed Church is accepting applications for its internship program for the 2016-2017 year. More information can be found here.

University Reformed Church is accepting applications for its internship program for the 2016-2017 year. More information can be found here.

We offer one internship program with four internship tracks:

Pastoral Ministry Track (full time): To train, equip, and prepare men for effective, responsible, and godly pastoral ministry in the local church through study, practice, counsel, mentoring, evangelism, and discipleship.

Campus Ministry Track (full time): To train, equip, prepare, and engage individuals for effective, responsible, and godly ministry to students on college campuses through study, practice, counsel, mentoring, evangelism, and discipleship.

International Ministry Track (full time): To train, equip, and prepare individuals, international students or prospective missionaries for effective, responsible, and godly cross-cultural ministry among international students.

Counseling Ministry Track (full or part time): To train, equip, and prepare individuals for effective, responsible, and godly counseling ministry through study, practice, counsel, mentoring, evangelism, and discipleship.

Applications are due January 31.

December 14, 2015

Sweet Little Jesus Boy

The following is a Christmas sermon I preached a couple years ago. I thought it might be worth posting again as Christmas approaches.

The following is a Christmas sermon I preached a couple years ago. I thought it might be worth posting again as Christmas approaches.

One of the Christmas traditions in my church growing up was that every year during the Christmas Eve service this one particular gentlemen would sing Sweet Little Jesus Boy. He was the right church member to sing the song. He was an old African American gospel singer, and he could sing it well. And even though it was a different style of music than all the other songs we would sing on Christmas Eve, it became a favorite of our almost entirely white congregation.

Sweet little Jesus Boy,

they made you be born in a manger.

Sweet little Holy Child,

didn’t know who You was.

Didn’t know you come to save us, Lord;

to take our sins away.

Our eyes was blind, we couldn’t see,

we didn’t know who You was.

The song was written in 1934 by Robert MacGimsey (1898-1979), a white man from Louisiana who made it his life’s work to learn, preserve, transcribe, and make accessible African American folk music from the South. MacGimsey wanted Sweet Little Jesus Boy to echo the sentiments of black Christians in the Civil War era. He once described his most famous song as more a meaning than a song: he pictured an aging black man whose life had been full of injustice “standing off in the middle of a field just giving his heart to Jesus in the stillness.”

The connection between our sufferings and Christ’s sufferings is powerful.

The world treat You mean, Lord;

treat me mean, too.

But that’s how things is down here,

we didn’t know t’was You.

And the refrain at the end of several of the verses has a haunting simplicity to it: “We didn’t who you was.”

Just seem like we can’t do right,

look how we treated You.

But please, sir, forgive us Lord,

we didn’t know ’twas You.

Sweet little Jesus Boy,

born long time ago.

Sweet little Holy Child,

and we didn’t know who You was.

Do you know who Jesus was?

Isaiah 9 hails the Messiah as the light of the world in a land of deep darkness. He is the child born under the oppression and eventual execution of the Roman government. He is our Wonderful Counselor and the Mighty God. He reveals to us the Everlasting Father. He is the Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his kingdom and peace there will be no end. He will rule with justice and righteousness from this time forth and forevermore.

So who was this child born of Mary?

A good teacher perhaps? That’s a popular answer: Jesus was really a humble prophet, a teacher of peace and justice. But some of his followers made up all these things about him–they invented the miracles and the exalted language about himself and the resurrection. Maybe the Christ of faith is completely different from the Jesus of history. Perhaps, but consider two major problems with this theory.

First, the only Jesus we have is the Jesus of faith. Virtually everything we know about Jesus is given to us through the eyes and pens of those who believed in him. So any attempt to find the historical Jesus behind the Jesus of faith is an attempt to find what we would like Jesus to be and not an attempt based on history. The only history we have about him comes from those who were changed by him. So either we are going to have to accept what Jesus’ followers said about him or admit that we can’t really know anything about this man.

The second problem with taking Jesus as simply a good moral teacher is that the people who argue for this approach almost never take into account all of Jesus’ teachings. What they mean is not so much that they respect Jesus as a teacher, but that Jesus was smart enough to say some of the same things they would say. So people appreciate Jesus the good teacher when he talks about turning the other cheek or walking the extra mile or giving to the needy. But they ignore all the parables Jesus told about weeping and gnashing of teeth and being cast into outer darkness. They love the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount, except they breeze past the places where Jesus says those who refuse to forgive will be punished, and those controlled by lust will be thrown into hell, and divorce except on the grounds of sexual immorality is wrong, and everyone who doesn’t build his house on Jesus is a fool. We gravitate to the peace on earth, good will toward men, and overlook the times when Jesus says his coming would bring division on the earth and turn mother against daughter, brother against brother, and father against son. No one should hail Jesus as a great moral teacher until he reads through all that Jesus taught. Then you can decide if still think he was a good teacher.

So who was the baby the Magi came to worship?

How would you answer that question? As I see it, there are two consistent answers and two inconsistent answers.

The first inconsistent response is to take part of Jesus: “I’ll take the teachings I like and ditch the rest. I’ll take his good deeds but not his hard words. I’ll take his love for humanity and not his desire to glorify himself.” Now, don’t get me wrong, you can pick and choose what you like about Jesus. People do it all the time, but it’s inconsistent. Don’t say you follow Jesus or even that you think he’s a great teacher. Be honest enough to say “I like the ‘judge not’ line, the love your enemies bit, and the cup of cold water thing, and that’s about it. Other than that, Jesus was a quack and not really very nice.” To say anything else is inconsistent.

The second inconsistent response is to accept that Jesus is the Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace, and accept that he is the perfect Son of God, the King of the nations, the Righteous Judge, and the hope of the world, and then live like it doesn’t matter. If you thought I was God–and I don’t think I need to assure you I’m not–you would be very interested in what I thought, and how I wanted you to live, and what I was like. You would talk to me and worship me and tell others about my true identity. And if you did none of those things, it would be right to question whether you really thought I was God. Faith is more than intellectual assent to certain doctrines, it is an entire life based on the conviction that these doctrines are true.

So who is the babe in the straw?

The first consistent response is to say, “He’s a nobody. He didn’t even exist. Or if he did exist, we can’t know anything about him. The gospels are myths and legends with no grounding in history. I may like the victory from defeat theme in the gospels, but I don’t need Jesus for that. I don’t really care who this Jesus is and neither should you. The billions of Christians singing to Jesus this week are worshiping a figment of their imagination.” That would be consistent.

And the other consistent response is to believe the Jesus is the Son of God, to worship him, and obey: “Yes, Jesus you are the image of the invisible God. You are the sacrifice for our sins. You are the only way to the Father. You are the resurrection and the life. You are the once and coming King.”

I can’t persuade you to say that for yourself. I can try to show you that it is not unreasonable, and is in fact, plausible, but if you don’t want to believe, you will find a reason not to believe. Just try to be consistent. My prayer is (1) that those who accept all these things as true will live and die as if they were, and (2) that those who don’t yet accept these things will ask God to help them understand if these things are so. Because wouldn’t it be terrible to meet Jesus on that great getting up morning, look him in the eye and then look at each other and confess, “We didn’t know who you was.”

Thinking Theologically About Islam

Islam is in the news. Again. Actually, I don’t think it ever left.

Islam is in the news. Again. Actually, I don’t think it ever left.

From jihad abroad to terrorism at home to questions surrounding refugees and immigration, there is no shortage of stories about Islam. Depending on who you listen to, you may think that most Muslims are out to kill you or that Muslims are among the most oppressed and ostracized people on the planet. Like almost every other controversial subject in our day, sizing up Islam has become a proxy for where one stands in the culture wars. Either America’s problem is that her leaders are weak, PC, and too afraid to tell the truth about Islam, or the problem is that vast swaths of flyover country are intolerant, prejudiced, and trigger-happy.

So where do we go from here?

Well, as Christians, it’s never a bad idea to go to the Bible. We won’t answer every policy question, but at least we can put a few important truths in place as we try to think Christianly about Islam.

Let’s briefly look at a pair of truths—one positive and one negative—under three different headings.

Identity

Muslims are made in the image of God and deserve to be treated with fairness, dignity, and respect. We mustn’t think of Muslims as mere foreigners or strangers, let alone as some sort of sub-human people who can be safely treated with contempt. They are fellow image bearers (Gen. 1:26-27), and we should love them as we would like to be loved (Matt. 22:39).

This does not mean that Muslims are our brothers and sisters. This familial terminology is strictly reserved in the New Testament for those who belong to the body of Christ (1 John 3:1-3, 9-10, 14-16; 5:1-5). Only with God as our Father and Jesus Christ as our reigning and redeeming older brother can we be adopted into the family of God (Heb. 2:11). Muslims may be friends, neighbors, co-workers, and even biological family members. But only those who are born again by the Spirit can rightly be called our spiritual brothers and sisters (John 1:12-13).

Faith

Muslims and Christians share important religious commonalities. Abraham is an important figure in both Christianity and in Islam. Both religions are staunchly monotheistic. Both recognize that Jesus was (at least) a miraculous prophet. Both believe in the abiding significance of inspired holy books.

This does not mean that Muslims and Christians worship the same God. The differences between Christianity and Islam are wide and deep. We disagree about the Bible, the Koran, the place of Mohammed, the person and work of Jesus Christ, what happened on the cross, what happens when you die, and how you get to heaven, to name only a few major differences. Christians worship a Triune God, one God in three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Matt. 28:19-20). In the Christian understanding, God is only truly known and truly worshiped when he is known and worshiped as the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ (John 1:18; 14:6-7; 9-11). The Christian God is the invisible God we behold as visible in the face of Christ (2 Cor. 4:4-6; Col. 1:15). On this side of the incarnation, all other conceptions of God are not merely incomplete, but idolatrous (John 8:39-59).

Welcome

Christians should look for opportunities to show love and compassion to our Muslim neighbors. I have gotten to know a number of Muslims in East Lansing over the years. They have all been friendly and easy to talk to. Some have lived here longer than I have. Others were just entering the country for work or study. I am thankful for ministries at our church—and in other churches—that seek to make Muslims and other newcomers feel welcomed, cared for, and at home (Rom. 12:9-18).

This does not mean the church has the responsibility to provide for all Muslims everywhere. Christians should do good to all people as they have opportunity, especially to the household of faith (Gal. 6:10). The church’s priority is the church, and the mission of the church is to make disciples and plant healthy churches (Acts 14:21-23; Rom. 15:19). In an effort to stir up one another to love and good deeds, we must not indict fellow Christians who have different opportunities and different callings. Being marked by Christlike compassion is not the same thing as providing social services for all needy people. To be open to helping anyone is not the same as an obligation to help everyone.

Obviously, my list of important truths is short. There is much more that could be said. But agreeing on at least these three (or six, I suppose) things would help Christians not only start off on the same foot, but perhaps help us avoid running off in the wrong direction.

December 13, 2015

Monday Morning Happy

December 10, 2015

Of the Father’s Love Begotten

Aurelius Clemens Prudentius was born in Spain in 348 A.D. He was loyal to the Roman Empire and considered it an “instrument in the hands of Providence for the advancement of Christianity.”

Aurelius Clemens Prudentius was born in Spain in 348 A.D. He was loyal to the Roman Empire and considered it an “instrument in the hands of Providence for the advancement of Christianity.”

Thirty-five years prior to his birth, Christianity had been granted full toleration under the Edict of Milan. With Constantine’s conversion, Christianity became the favored religion of the Empire, a change that is oft maligned by younger evangelicals suspicious of “Christendom,” but must have been a welcome relief and answer to prayer for the beleagured saints in the fourth century.

Prudentius was trained to be a lawyer and rose to high office, serving as a powerful judge. He rose through the ranks of the state and finished his civil career as a court official for the Christian Emperor Theodosius.

At the age of fifty-seven, at the height of his power and prestige, Prudentius grew weary of civic life and considered his life thus far to have been a waste. He was having a midlife crisis (or, given the age span at the time, more like an almost-at-the-end-of-my-life crisis). So the successful lawyer, judge, and civil servant retired to write hymns and poetry. For the last decade of his life, before his death around 413, Prudentius wrote some of the most beautiful hymns of his day.

His poetry was treasured throughout the Middle Ages. His collection of twelve long poems (Cathemerinon), one for each hour of the day, became the foundation for several of the office hymns of the church. But without a doubt, Prudentius’ best known hymn today is Corde Natus Ex Parentis–Of the Father’s Love Begotten.

It was translated into English by John Mason Neale and Henry Baker in the 1850s. It was included in the book Hymns Ancient and Modern and given the plainsong chant-like melody Divinum Mysterium (Divine Mystery), which may date back as far as the twelfth century.

The hymn/poem originally contained nine verses. The song tells the story of redemption. Verse one speaks of the Son’s eternal nature. Verse two is about creation. Verse three chronicles the fall. Verse four moves into redemption with the virgin birth. Verse five links the Christ child to ancient prophecies. Verse six is a chorus of praise to the Messiah. Verse seven warns of final judgment for the wicked. Verse eight tells of men, women, and children singing their songs of praise. And verse nine concludes the hymn with a song of victory to Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Most Christians will recognize many of the verses, but sadly not all.

Of the Father’s love begotten,

Ere the worlds began to be,

He is Alpha and Omega,

He the source, the ending He,

Of the things that are, that have been,

And that future years shall see,

Evermore and evermore!

At His Word the worlds were framèd;

He commanded; it was done:

Heaven and earth and depths of ocean

In their threefold order one;

All that grows beneath the shining

Of the moon and burning sun,

Evermore and evermore!

He is found in human fashion,

Death and sorrow here to know,

That the race of Adam’s children

Doomed by law to endless woe,

May not henceforth die and perish

In the dreadful gulf below,

Evermore and evermore!

O that birth forever blessed,

When the virgin, full of grace,

By the Holy Ghost conceiving,

Bare the Saviour of our race;

And the Babe, the world’s Redeemer,

First revealed His sacred face,

evermore and evermore!

This is He Whom seers in old time

Chanted of with one accord;

Whom the voices of the prophets

Promised in their faithful word;

Now He shines, the long expected,

Let creation praise its Lord,

Evermore and evermore!

O ye heights of heaven adore Him;

Angel hosts, His praises sing;

Powers, dominions, bow before Him,

and extol our God and King!

Let no tongue on earth be silent,

Every voice in concert sing,

Evermore and evermore!

Righteous judge of souls departed,

Righteous King of them that live,

On the Father’s throne exalted

None in might with Thee may strive;

Who at last in vengeance coming

Sinners from Thy face shalt drive,

Evermore and evermore!

Thee let old men, thee let young men,

Thee let boys in chorus sing;

Matrons, virgins, little maidens,

With glad voices answering:

Let their guileless songs re-echo,

And the heart its music bring,

Evermore and evermore!

Christ, to Thee with God the Father,

And, O Holy Ghost, to Thee,

Hymn and chant with high thanksgiving,

And unwearied praises be:

Honour, glory, and dominion,

And eternal victory,

Evermore and evermore!

I couldn’t find a real good rendition of the song online. The clip below is not much to look at (ok, there’s really nothing to look at), but the sound is lovely.

December 9, 2015

Top Ten Books of 2015

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of Christian books published each year, let alone every interesting book published in 2015. I read a lot of books, but there are plenty of worthy titles that I never touch (and never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year (including the last few months of the previous year).

This list is not meant to assess the thousands of Christian books published each year, let alone every interesting book published in 2015. I read a lot of books, but there are plenty of worthy titles that I never touch (and never hear of). This is simply a list of the books (Christian and non-Christian, but all non-fiction) that I thought were the best in the past year (including the last few months of the previous year).

When I say “best” I have several questions in mind:

• Was this book well written and enjoyable to read?

• Did I find it personally challenging, illuminating, edifying, or entertaining?

• Is it a book I am likely to reread or consult often?

• Do I see myself frequently recommending this book to others?

Undoubtedly, the “best” books reflect my interests and inklings. This doesn’t mean I agree with every point in all these books, but it does mean I found them helpful and insightful. There is nothing scientific about my list, but here goes:

Honorable Mentions (Scotland edition!)

Ronald Lyndsay Crawford, The Lost World of John Witherspoon: Unravelling the Snodgrass Affair, 1762 to 1776 (Aberdeen University Press)

Jane Dawson, John Knox (Yale University Press)

John Macleod, Scottish Theology in Relation to Church History (Banner of Truth, reprinted)

Top Ten

10. Matt Fitzgerald, 80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training Slower (New American Library). Little known fact: although I don’t usually mention them on my blog, I read a bunch of running/swimming/biking books. I go through them like Skittles. This book in particular got me thinking about a new way of training. Who wouldn’t want to run faster by running slower! The basic gist: make 80% of your running easy and 20% hard. When you get into the details of the concept, you see it’s not quite that simple, but as a general rule of thumb it makes a lot of sense. At the very least, this book described my running perfectly–never too easy, never extremely hard, almost always moderately difficult. I’m eager to try a different approach.

10. Matt Fitzgerald, 80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training Slower (New American Library). Little known fact: although I don’t usually mention them on my blog, I read a bunch of running/swimming/biking books. I go through them like Skittles. This book in particular got me thinking about a new way of training. Who wouldn’t want to run faster by running slower! The basic gist: make 80% of your running easy and 20% hard. When you get into the details of the concept, you see it’s not quite that simple, but as a general rule of thumb it makes a lot of sense. At the very least, this book described my running perfectly–never too easy, never extremely hard, almost always moderately difficult. I’m eager to try a different approach.

9. David Maraniss, Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story (Simon and Schuster). Born in Detroit, Maraniss is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and associate editor at the Washington Post. In this extremely readable account of Detroit circa 1962-64, one sees a picture of a vibrant city with the hustle and bustle of a booming auto industry and the cultural cache of the Motown music scene. For people who only know what Detroit is (and there are good things happening even now), the story Maraniss tells can seem other worldly. Did you know Detroit was the U.S. choice for the 1968 summer Olympics? Did you know Martin Luther King Jr. first gave his “I have a dream” speech–at least many of the lines from the stirring conclusions–in Detroit in 1963, a few months before reworking the message for the Lincoln Memorial later that summer? Did you know the Ford Rotunda, which as destroyed in 1962, once boasted of being the fifth most popular tourist destination in the United States, receiving more visitors in the 1950s than the Statue of Liberty? More sobering, did you know that already in 1963s, researchers at Wayne State University were warning that Detroit–before the race riots and before the collapse of the automobile industry–was headed for major trouble and rapid depopulation? You don’t have to be a Michigander to find this a fascinating read.

9. David Maraniss, Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story (Simon and Schuster). Born in Detroit, Maraniss is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and associate editor at the Washington Post. In this extremely readable account of Detroit circa 1962-64, one sees a picture of a vibrant city with the hustle and bustle of a booming auto industry and the cultural cache of the Motown music scene. For people who only know what Detroit is (and there are good things happening even now), the story Maraniss tells can seem other worldly. Did you know Detroit was the U.S. choice for the 1968 summer Olympics? Did you know Martin Luther King Jr. first gave his “I have a dream” speech–at least many of the lines from the stirring conclusions–in Detroit in 1963, a few months before reworking the message for the Lincoln Memorial later that summer? Did you know the Ford Rotunda, which as destroyed in 1962, once boasted of being the fifth most popular tourist destination in the United States, receiving more visitors in the 1950s than the Statue of Liberty? More sobering, did you know that already in 1963s, researchers at Wayne State University were warning that Detroit–before the race riots and before the collapse of the automobile industry–was headed for major trouble and rapid depopulation? You don’t have to be a Michigander to find this a fascinating read.

8. Gary Scott Smith, Religion in the Oval Office: The Religious Lives of American Presidents (Oxford University Press). I confess that I haven’t made my way through the whole book, but I’ve poked around a good chunk of it. The book is well researched, balanced, and relentlessly interesting. Smith covers 11 presidents (Adams, Madison, Adams, Jackson, McKinley, Hoover, Truman, Nixon, Bush 41, Clinton, Obama) and makes a compelling case that religion–though vastly different in many instances–was nevertheless genuinely important for each of these men.

8. Gary Scott Smith, Religion in the Oval Office: The Religious Lives of American Presidents (Oxford University Press). I confess that I haven’t made my way through the whole book, but I’ve poked around a good chunk of it. The book is well researched, balanced, and relentlessly interesting. Smith covers 11 presidents (Adams, Madison, Adams, Jackson, McKinley, Hoover, Truman, Nixon, Bush 41, Clinton, Obama) and makes a compelling case that religion–though vastly different in many instances–was nevertheless genuinely important for each of these men.

7. Terry Lindvall, God Mocks: A History of Religious Satire from the Hebrew Prophets to Stephen Colbert (New York University Press). Besides providing a number of examples that make you say, “Wow, I can’t believe they wrote that,” this academic work is especially helpful in simply making the case (rather obvious when you know what to look for) that Christianity has a long history of using satire to make a point. Many Christians instinctively recoil at the thought of religious satire, but Lindvall argues that being a Christian satirist is rooted in the nature of God: we worship a God who–like it or not–mocks (at least at times). Lindvall, the C.S. Lewis Chair of Communication and Christian Thought at Virginia Wesleyan College, plots his historical examples along an x-axis which moves left to right from ridicule to moral purpose and a y-axis which moves upward from rage to humor. He maintains that landing in the upper most quadrant (humor with a moral purpose) is where satire is most salutary.

7. Terry Lindvall, God Mocks: A History of Religious Satire from the Hebrew Prophets to Stephen Colbert (New York University Press). Besides providing a number of examples that make you say, “Wow, I can’t believe they wrote that,” this academic work is especially helpful in simply making the case (rather obvious when you know what to look for) that Christianity has a long history of using satire to make a point. Many Christians instinctively recoil at the thought of religious satire, but Lindvall argues that being a Christian satirist is rooted in the nature of God: we worship a God who–like it or not–mocks (at least at times). Lindvall, the C.S. Lewis Chair of Communication and Christian Thought at Virginia Wesleyan College, plots his historical examples along an x-axis which moves left to right from ridicule to moral purpose and a y-axis which moves upward from rage to humor. He maintains that landing in the upper most quadrant (humor with a moral purpose) is where satire is most salutary.

6. Sean Michael Lucas, For a Continuing Church: The Roots of the Presbyterian Church in America (P&R Publishing). With a few years of doctoral work under my belt, I have a much better eye for good history than I did before, and I can tell you that Sean Lucas is a very good historian. His prose is fair, readable, insightful, and steeped in primary sources. I loved reading this book because it explains the origins of my new denominational home. But it’s much more than a PCA book. It’s nothing less than a history of Southern Presbyterianism (and some Northern Presbyterianism) in the twentieth century. I’m excited to reread this book and keep learning.

6. Sean Michael Lucas, For a Continuing Church: The Roots of the Presbyterian Church in America (P&R Publishing). With a few years of doctoral work under my belt, I have a much better eye for good history than I did before, and I can tell you that Sean Lucas is a very good historian. His prose is fair, readable, insightful, and steeped in primary sources. I loved reading this book because it explains the origins of my new denominational home. But it’s much more than a PCA book. It’s nothing less than a history of Southern Presbyterianism (and some Northern Presbyterianism) in the twentieth century. I’m excited to reread this book and keep learning.

5. Rosaria Butterfield, Openness Unhindered: Further Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert on Sexual Identity and Union with Christ (Crown & Covenant). What can you say about Rosaria? She is so honest, so unflinchingly truthful, so tender, so realistic, so hopeful, so wise, so down to earth, and so heavenly minded. As you try to sort through the wreckage of the sexual revolution–either in the culture or in your own life (or both)–make sure this is one of the books you read.

5. Rosaria Butterfield, Openness Unhindered: Further Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert on Sexual Identity and Union with Christ (Crown & Covenant). What can you say about Rosaria? She is so honest, so unflinchingly truthful, so tender, so realistic, so hopeful, so wise, so down to earth, and so heavenly minded. As you try to sort through the wreckage of the sexual revolution–either in the culture or in your own life (or both)–make sure this is one of the books you read.

4. Edward T. Welch, Side by Side: Walking with Others in Wisdom and Love (Crossway). I love simple books that aren’t simplistic. This is a terrific book about loving one another, about helping hurting people, about getting help as hurting people, about being a good neighbor, and about being the body of Christ. Our whole staff is reading the book this semester. The insights aren’t new, but the reminders are extremely helpful and the points of application unusually practical and life giving.

4. Edward T. Welch, Side by Side: Walking with Others in Wisdom and Love (Crossway). I love simple books that aren’t simplistic. This is a terrific book about loving one another, about helping hurting people, about getting help as hurting people, about being a good neighbor, and about being the body of Christ. Our whole staff is reading the book this semester. The insights aren’t new, but the reminders are extremely helpful and the points of application unusually practical and life giving.

3. Barton Swaim, The Speechwriter: A Brief Education in Politics (Simon and Schuster). I started and finished this in the same day. The book is hilarious and cringe-worthy and brutal and restrained and sad and optimistic all at the same time. Most of all, it’s well written, and every page is interesting.

3. Barton Swaim, The Speechwriter: A Brief Education in Politics (Simon and Schuster). I started and finished this in the same day. The book is hilarious and cringe-worthy and brutal and restrained and sad and optimistic all at the same time. Most of all, it’s well written, and every page is interesting.

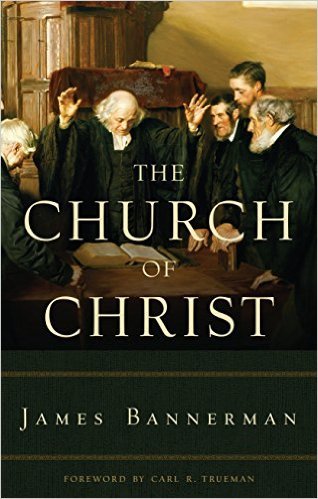

2. James Bannerman, The Church of Christ (Banner of Truth, reprinted). I read an earlier (much less attractive) printing of this book (by a different publisher) several years ago, and since then I’ve gone back to Bannerman time after time. There is simply no more thoughtful book on ecclesiology from a Presbyterian perspective. It’s so good that even Congregationalists will benefit from it. Reformed pastors need this book on their shelves.

2. James Bannerman, The Church of Christ (Banner of Truth, reprinted). I read an earlier (much less attractive) printing of this book (by a different publisher) several years ago, and since then I’ve gone back to Bannerman time after time. There is simply no more thoughtful book on ecclesiology from a Presbyterian perspective. It’s so good that even Congregationalists will benefit from it. Reformed pastors need this book on their shelves.

1. Shelby Steele, Shame: How America’s Past Sins Have Polarized Our Country (Basic Books). More than any other book I read this year, this is the one I wanted to read through again in a small group. I’d love to hear what my friend (or enemies) think about Steele’s poignant account of racism in his own experience (he’s African American) and his argument that today’s liberalism is not about helping people like him as much as it is about moving from relativism to dissociation to legitimacy to power. This is a book to be read slowly, discussed, digested, and–though I don’t know anything about Steele’s personal faith or lack thereof–dare I say, even prayed over.

1. Shelby Steele, Shame: How America’s Past Sins Have Polarized Our Country (Basic Books). More than any other book I read this year, this is the one I wanted to read through again in a small group. I’d love to hear what my friend (or enemies) think about Steele’s poignant account of racism in his own experience (he’s African American) and his argument that today’s liberalism is not about helping people like him as much as it is about moving from relativism to dissociation to legitimacy to power. This is a book to be read slowly, discussed, digested, and–though I don’t know anything about Steele’s personal faith or lack thereof–dare I say, even prayed over.

December 7, 2015

Can that be Right? The Use of Old Testament Prophecy in the New Testament

It’s Christmas season and that means renewed attention on Messianic prophecy. Ah, the familiar sounds of “a virgin shall give birth,” “the government shall be upon his shoulders,” and good ole “Bethlehem Ephrathah.” It makes a churchgoer feel all warm and cuddly inside.

It’s Christmas season and that means renewed attention on Messianic prophecy. Ah, the familiar sounds of “a virgin shall give birth,” “the government shall be upon his shoulders,” and good ole “Bethlehem Ephrathah.” It makes a churchgoer feel all warm and cuddly inside.

And frankly, a bit confused.

If we’re honest, the way the New Testament uses the Old Testament seems a little far-fetched. I mean, we can see, just like the scribes did, that Micah 5:2 is a foretelling of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem (Matt. 2:1-6), but was Hosea really making a prediction about the Christ just because he happened to mention “Egypt” (Hos. 11:1) and Jesus’ family fled to Egypt (Matt. 2:15)? If we interpreted Scripture like Matthew does, we’d be chased out of our pulpits and small groups, right?

The New Testament’s use of the Old Testament is a complicated subject. Even evangelical scholars don’t agree on all the particulars of the best approach (see for example this book and D.A. Carson’s review). Still, there are several principles, clarifications, and reminders that can help us make sense of the Apostles’ seemingly willy-nilly use of the Old Testament.

(For the most part, the following points were gleaned from Doug Moo’s chapter “The Problem of Sensus Plenior” in Hermeneutics, Authority, and Canon [edited by D.A. Carson and John Woodbridge]. Jared Compton makes many of the same points in his fine Themelios piece “Shared Intentions? Reflections on Inspiration and Interpretation in Light of Scripture’s Dual Authorship.”)

1. Keep in mind the NT’s purpose in referencing the OT. We often think every time the OT is referenced it must mean the NT author is trying to exegete the OT passage. But there is no rule of inerrancy which says the NT author must always be attempting to give the correct interpretation of a given passage. The NT author may not be attempting an interpretation at all. If someone asks me, “How is the editing work going” and I say, “It’s tedious–line upon line, precept upon precept” this doesn’t mean I’m trying to exegete Isaiah 28:10. I’m simply employing the familiar language of a familiar passage.

2. Along these lines, remember the NT often uses the OT simply as a vehicle of expression. The NT writers were hugely familiar with the OT. It’s no wonder they employed its vocabulary. In the same way, Westerners might use a line from Shakespeare or the Bible because it is familiar, but without intending to explain its context or original meaning.

3. The NT may press home the significance of a passage without trying to explain its original meaning. For example, Moo points to Paul’s use of Deuteronomy 25:4 (“You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain”) in 1 Corinthians 9:9. Critics argue that Paul is taking the Law of Moses out of context by saying this passage is about paying ministers. But surely Paul is justified in pulling a fair inference out of the passage and applying it to his own context.

4. We must allow for a broader view of “fulfillment” language. A lot of trouble could be avoided if we understood that the use of plēroō (fulfilled) does not have to mean “and so this verse predicted that Jesus would do or say this thing that just happened.” As Moo says, “The word is used in the New Testament to indicate the broad redemptive-historical relationship of the new, climactic revelation of God in Christ to the preparatory, incomplete revelation to and through Israel” (191). In other words, “fulfilled” does not mean the OT text in question is a direct prophecy. Consequently, Jesus flight to Egypt can fulfill Hosea 11:1, not because Hosea ever intended to predict a Messianic trip down south, but because Jesus is God’s greater Son who is the embodiment of a new Israel. Jesus is on an Exodus journey of his own. Hosea did not predict the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt, nor does Matthew suggest the prophet meant to do so. But Matthew does see that the story of Israel’s exodus, alluded to in Hosea, is brought to its full redemptive-historical revelation in Christ.

5. Similarly, some OT passages are fulfilled typologically. This is different than allegory. And allegory looks for meaning behind the text where typology finds a developed meaning that is rooted in the text (see Moo 195). Jesus’ passion can be seen as a fulfillment of David’s heart cry in Psalm 22 not because David thought he was predicting the death of the Messiah, but because David, as the king and as the promised progenitor of the Messiah, was a type of Christ whose cries anticipated the final dereliction of David’s greater son.

6. OT prophecy is full of examples where there is a near and far fulfillment. Isaiah 40, for example, was a word of comfort about the return from Babylon, but later we see it also was a word about John the Baptist who would prepare the way for the Messiah (Mark 1:2-3). Much of the prophetic witness implicitly anticipates a future, fuller, often eschatological fulfillment. Isaiah may not have known that his words about the virgin were Messianic, but this does not mean he’d be surprised to know they were. Israel was always waiting for the everlasting kingdom and the final Deliverer. I think the prophets understood that what they foretold (and forth-told) was for their day, but it could be for the future as well.

Two Other Questions

Of course, the foregoing principles raise two thorny questions:

1) Did the OT authors say more than they knew? That is, is there a meaning in some OT texts that we know by the NT but would have been unknown to the authors? Excellent scholars like Walter Kaiser have argued strenuously that there can be no double meanings or fuller meanings in the OT text. While Kaiser is certainly right to insist that many problem passages can be “solved” by paying careful attention to the original context and the theological background, I agree with Moo and others who argue, “There are places where the New Testament attributes to Old Testament text more meaning than it can be legitimately inferred the human author was aware of” (201).

Does this mean we are doomed to “hermeneutical nihilism?” I don’t think so. First, every interpretation of Scripture must be constrained by Scripture. Many scholars now argue for “a canonical approach” to understanding the NT use of the OT. The Bible is a literary whole. In some sense, the OT is an incomplete, unfinished book. But once the whole is complete, we are able to make better sense of earlier parts and see things that the authors at an “unfinished” time may have missed. Second, we must remember that none of this undermines authorial intent. The NT authors did not find meanings in the OT the original authors never intended. Perhaps the human authors were unaware of the fullness of their words, but do not forget there is also a Divine author. Under the inspiration of the Spirit, the NT writers were able to understand the authorial intent that may not have been fully known to the OT human authors. The NT does not find a meaning that isn’t there, only (and on occasion) a meaning that was not obvious to one half of the writing team.

2) The second question raised by this discussion is whether we can imitate the hermeneutic employed at times by the NT writers. With Moo, I would give a firm “that depends.” On the one hand, we do not have the Spirit’s inspiration to know the mind of God in the same way. So we should be extremely cautious about finding “fuller” meanings in the text. On the other hand, we should read the Bible with same theologically informed, salvation-historical, whole canon approach that we see employed in the NT use of the OT (Moo 206, 210).

Lessons Learned

One of the practical lessons from all this is that we should avoid a simplistic approach to OT-NT fulfillment. Sometimes with good apologetic and evangelistic motives we will point to all the OT prophecies about Christ and then run down a list of all the NT fulfillments. There is truth here, but if we set things up as “here’s the prediction; here’s the prediction come true” we are bound to confuse people. We may even cause people to doubt the prophetic witness rather than trust it. All the prophecies cited in the NT are true and truly fulfilled, but it’s all a bit more complicated (and actually more glorious) than we sometimes let on.

The other lesson is that we need not be embarrassed to use a strong theological lens on top of our appropriate grammatical-historical lens. This is not an invitation to allegory or a reason to search for hidden spiritual meanings like Super Mario finds his mushrooms. But it does mean we should, like the NT writers did, read the Bible across the whole Bible. We should see Jesus in all of Scripture. We should read the end in the light of the beginning and the beginning in view of the end. Above all, we can celebrate that Jesus is the perfect fulfillment of all that was imperfectly prefigured in the OT. This alone will make a fuller, deeper, richer Christmas story.