Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 37

June 8, 2016

Book Briefs

Long plane rides are no fun, but they do mean more time to read.

Grant Wacker, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation (Belknap/Harvard, 2014). This is one of those books that sat on my shelf for over a year. I read a few pages here and there, but never found the time to get through it cover to cover. I was about to give up on and put it on my resource shelf (i.e., to be consulted, not read). But at last minute I threw the book in my bag before flying to Geneva two weeks ago. I’m very glad I did. I couldn’t put it down. Even when I should have been sleeping, I kept reading. This is not a typical biography that moves chronologically through the life of the subject. Instead, it’s an interpretive look at why Billy Graham matters and what his life says about the relationship between religion and American culture. Wacker is honest about Graham’s faults, while remaining sympathetic to his message and finding aspects of his character and ministry inspirational and worthy of emulation. The last section on “Cracks in the Marble” and “Contours in the Marble” was hugely instructive. While one could wish for more of a theological lens in Wacker’s analysis, that’s not the book he set out to write. The book he did mean to write, he wrote very well.

Grant Wacker, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation (Belknap/Harvard, 2014). This is one of those books that sat on my shelf for over a year. I read a few pages here and there, but never found the time to get through it cover to cover. I was about to give up on and put it on my resource shelf (i.e., to be consulted, not read). But at last minute I threw the book in my bag before flying to Geneva two weeks ago. I’m very glad I did. I couldn’t put it down. Even when I should have been sleeping, I kept reading. This is not a typical biography that moves chronologically through the life of the subject. Instead, it’s an interpretive look at why Billy Graham matters and what his life says about the relationship between religion and American culture. Wacker is honest about Graham’s faults, while remaining sympathetic to his message and finding aspects of his character and ministry inspirational and worthy of emulation. The last section on “Cracks in the Marble” and “Contours in the Marble” was hugely instructive. While one could wish for more of a theological lens in Wacker’s analysis, that’s not the book he set out to write. The book he did mean to write, he wrote very well.

Yuval Levin, The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism (Basic Books, 2016). I finished this one on the plane ride home. Levin, a former White House and congressional staffer and now an editor (National Affairs), a contributing editor National Review and Weekly Standard), and a Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, has written an original and thoughtful book that thinkers on both sides of the political aisle should read carefully. Although Levin is a conservative, he faults both the Left and the Right for being “blinded by Nostalgia” and failing to propose meaningful solutions that do more than pedal a narrative of decline and pine for the good old days. An illuminating read.

Yuval Levin, The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism (Basic Books, 2016). I finished this one on the plane ride home. Levin, a former White House and congressional staffer and now an editor (National Affairs), a contributing editor National Review and Weekly Standard), and a Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, has written an original and thoughtful book that thinkers on both sides of the political aisle should read carefully. Although Levin is a conservative, he faults both the Left and the Right for being “blinded by Nostalgia” and failing to propose meaningful solutions that do more than pedal a narrative of decline and pine for the good old days. An illuminating read.

J.C. Ryle, Simplicity in Preaching (Banner of Truth, 2010). Originally published in 1888, it’s amazing how relevant Ryle’s advice still feels. And it is easy to follow. When it came to direct prose, straightforward outlines, and memorable phrases, Ryle practiced what he preached. I can’t think of a pastor or ministerial student who wouldn’t be helped by setting aside a half hour to read this little booklet.

J.C. Ryle, Simplicity in Preaching (Banner of Truth, 2010). Originally published in 1888, it’s amazing how relevant Ryle’s advice still feels. And it is easy to follow. When it came to direct prose, straightforward outlines, and memorable phrases, Ryle practiced what he preached. I can’t think of a pastor or ministerial student who wouldn’t be helped by setting aside a half hour to read this little booklet.

John Currid, Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament (Crossway, 2013). In preaching through Exodus for almost a year–I started in August and preached on Exodus 17:1-7 last Sunday–I’ve been helped by Against the Gods and by Currid’s more larger work Ancient Egypt in the Old Testament (Baker Academic, 1997). Currid is well versed in the scholarship of ancient Egypt, yet conservative in handling the biblical text. He is also pastoral (especially in the Crossway book) in applying the fruits of academic study to the task of teaching and preaching. While it would be a mistake to make your next study through Exodus a weekly exercise in dissecting the deities of ancient Egypt, there are many valuable insights from Currid that will help you better understand how the Old Testament, and Exodus in particular, is a devastating polemic against the false gods of the nations.

John Currid, Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament (Crossway, 2013). In preaching through Exodus for almost a year–I started in August and preached on Exodus 17:1-7 last Sunday–I’ve been helped by Against the Gods and by Currid’s more larger work Ancient Egypt in the Old Testament (Baker Academic, 1997). Currid is well versed in the scholarship of ancient Egypt, yet conservative in handling the biblical text. He is also pastoral (especially in the Crossway book) in applying the fruits of academic study to the task of teaching and preaching. While it would be a mistake to make your next study through Exodus a weekly exercise in dissecting the deities of ancient Egypt, there are many valuable insights from Currid that will help you better understand how the Old Testament, and Exodus in particular, is a devastating polemic against the false gods of the nations.

June 6, 2016

Should I Attend a Homosexual Wedding If the Service Is Completely Secular?

In speaking about homosexuality in my church and in different venues around the country (and sometimes around the world), the most common question I’ve received (by far) is whether a Christian who believes homosexual behavior is wrong should attend a gay wedding.

In speaking about homosexuality in my church and in different venues around the country (and sometimes around the world), the most common question I’ve received (by far) is whether a Christian who believes homosexual behavior is wrong should attend a gay wedding.

The question is often a painful one. It’s one thing to hold to biblical views on marriage and sexuality in a culture that increasingly hates those views. That’s hard enough. But to tell your son or daughter or brother or sister or mom or dad or cousin or buddy from college that you won’t attend their (ideally) once-in-a-lifetime event feels like too much offense to give and too much of a burden to bear. I sympathize with sincere believers who really want to honor God and communicate love to their friends and family at the same time. These are difficult days to be Christians with convictions about marriage.

And yet, as much as we can feel the weight and the heartache of the question, the answer should be no.

I’ve written on this subject before, but my response assumed in part that the wedding ceremony would have some religious component to it:

A wedding ceremony, in the Christian tradition, is first of all a worship service. So if the union being celebrated in the service cannot be biblically sanctioned as an act of worship, we believe the service lends credence to a lie. We cannot in good conscience participate in a service of false worship. I understand that does not sound very nice, but the conclusion follows from the premise, namely, that the “marriage” being celebrated is not in fact a marriage and should not be celebrated.

That was the gist of my argument. I went on in the article to address a number popular objections (e.g., Jesus hung out with sinners; we should fear being contaminated by the world; we don’t want to turn people off to God’s love), and at the end I made a passing reference to ceremonies that were not religious in nature. But I didn’t deal head on with the question posed in the title of this post: What if the wedding is thoroughly secular, does that change the moral calculus?

You may be thinking, “I get your point about a Christian wedding ceremony. But my friend doesn’t claim to be a Christian. He and his partner are total agnostics. Their service won’t be religious in the least. I’m not going to worship God. I’m just going so my friend knows I care about him.” I’ve heard conservative Christians make similar arguments several times. I see their appeal. I don’t, however, find them intellectually or spiritually compelling.

In short, as personally painful as it may be, and as much as the world will call us names and castigate our motives, those who believe marriage is between a man and a woman should not attend a ceremony that purports to be the marrying of a man and a man or a woman and a woman, even if that ceremony is completely secular in nature.

Why such a “hard line” stance? Here are three reasons.

1. The purpose of a wedding ceremony is to celebrate and solemnize. No matter the formal liturgy or no liturgy at all, the reason a couple puts together a wedding ceremony is so that others can join in celebrating with them. Isn’t this why invitations speak of “honoring us with your presence” or “join us as we celebrate”? Isn’t this why at a reception the couple invariably takes time to thank all their friends and family for coming? Isn’t this why we throw rice or blow bubbles or release balloons? Isn’t this why we wait in line to give the newlyweds a hug?

Two (unmarried, of age) people can fill out the necessary paperwork and get married at the courthouse or on a beach or in the basement without any planning, any fanfare, or any guests. But hardly anyone gets married in this way. Instead they plan a party. They line up food and drink and music and invite their friends. There is nothing in the secular nature of a wedding ceremony that makes it less of a celebration. And there’s the rub: how can we celebrate what we deem to be a serious moral transgression and an definitional impossibility?

2. Wedding ceremonies are almost always public in nature. Many Christians are quick to parse out their support: “They know where I stand. They know what I believe. I’m not coming to support the marriage. I’m coming to support my son and let him know that I still love him.” Again, I sympathize with this reasoning and do not dismiss lightly. But in addition to minimizing the previous point about celebration and solemnization, this line of thinking ignores the public aspect of a wedding (and no matter how small the event, if you are being invited to attend it is a public ceremony).

Attendees at a wedding bear witness to the exchanging vows and the making of promises. In a Christian understanding, they do so before God and man. In a secular environment, they still do so before a watching world. Why do we go to the trouble of having ceremonies for graduation or retirement or Super Bowl champions? Because the occasion calls for celebration, solemnization, and public recognition. Whatever beliefs we may espouse privately, when we attend a wedding we state publicly that the union, which the events creates and commemorates, is legitimate and deserving of honor.

Consider an analogy. Suppose your friend was an avowed racist. You’ve known this friend for a long time. You’ve told him before that you don’t agree with his racist views. He finds those conversations offensive and hurtful, but the friendship endures. One day he invites you to his white robe and hood ceremony at the local chapter of the Klan (I have no idea if they have such a thing, but let’s imagine they do). Their will be a small event at the local park to bestow this rank upon your friend. He would love for you to attend. Will you? I doubt any of us would. (1) We’d be too embarrassed to be seen in public at such an event, no matter what we’ve said in private about it. And (2) however much we care for our friend, we can’t have anything to do with an event that is so repugnant to the beliefs we hold dear.

Yes, I understand analogies are imperfect. No, I am not suggesting that racism and attending a gay wedding are the same thing. The point of a negative analogy like this is to get you to reconsider one position you do like by comparing it with one you don’t like. Why would we normalize what would be better stigmatized? How can we publicly endorse what we claim to privately condemn?

3. The stark either/or options are not of our making. The emotional plea is strongly felt by friends and family members who want to maintain biblical fidelity without burning bridges: “If you really loved me, you would be there. You say you care about me, but you don’t care to show up on the most important day of my life. If you can’t be happy for me, how can we have a real relationship?” Most evangelicals don’t wake up in the morning looking for ways to compromise. It happens with a tug here and a pull there, often with the best of intentions, usually because of people we love. Who wants to burn bridges? Who wants to be a hater? Who likes upsetting people we care about?

But this is where we need to remember that the either/or options were not (I trust) our idea. Not supporting a child’s decision in one area does not mean you are no longer interested in supporting him or her in other areas. Loving across our differences is a two way street. If traditional Christians have to learn to love gay and lesbian friends and family members despite decisions they disagree with, then gays and lesbians should learn to love their Christian friends and families despite decisions they disagree with. We should take time to hear why our attendance means so much to them. And then, hopefully, they will take time to hear why our faith in Christ and obedience to the Bible mean so much to us. We won’t agree. But maybe we can begin to almost, possibly, just a little bit, agree that we are going to be in this for the long haul so we better find out how to care for each other, even when we think the other person is living according to convictions that we can’t support.

“I can’t say yes to your wedding invitation, but I’d love to have you over for dinner.” Give that a shot.

June 5, 2016

Monday Morning Humor

Kids, there are worse things to do with your summer vacation. Just be sure to pick up the mess when you’re done.

June 2, 2016

Theological Primer: Freedom of the Will

From time to time I make new entries into this continuing series called “Theological Primer.” The idea is to present big theological concepts in around 500 words. Today we look at the human will and whether it is free or bound (or in some sense both).

*******

Since at least the time of Augustine (354-430), Christian theologians argued about the nature of the fallen human will: is it free or is it bound? In order to make sense of this question, medieval scholastics like Peter Lombard (ca 1096-1160) and Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) made distinctions among different types of necessity, distinctions John Calvin (1509-1564) would later use to explain how man could be enslaved to sin and at the same time responsible for his sin.

Since at least the time of Augustine (354-430), Christian theologians argued about the nature of the fallen human will: is it free or is it bound? In order to make sense of this question, medieval scholastics like Peter Lombard (ca 1096-1160) and Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) made distinctions among different types of necessity, distinctions John Calvin (1509-1564) would later use to explain how man could be enslaved to sin and at the same time responsible for his sin.

Our sin, which the fallen will chooses by necessity, is also voluntary because the choice is owing to our own corruption. There is no external coercion, no outside compulsion which makes us sin. The will, though bound to wickedness on this side of Eden, is still self determined.

Francis Turretin (1623-1687) argued to the same effect, postulating six different types of necessity. The will can be said to be free even if it is bound by a moral necessity (along with the necessity of dependence upon God, rational necessity, and necessity of event) so long as it is free from physical necessity and the necessity of coaction. That is to say, if the intellect has the power of choice (freedom from physical necessity) and the will can be exercised without external compulsion (freedom from the necessity of coaction) then our sins can be called voluntary, and we can be held responsible for them.

Arminian critics sometimes accuse Calvinists of believing that when people are raped, maimed, murdered, and tortured that it is ultimately God who performs these heinous acts. What this criticism misses, however, is the distinction between remote and primary causes. No thoughtful Calvinists would say God abuses innocent people. God is never the doer of evil. Reformed theologians have always made clear there is a difference between the role of God in ordaining what comes to pass and the role of human agency in actually and voluntarily performing the ordained action. Herod and Pontius Pilate conspired against Jesus in accordance with divine predestination, but their conspiracy was still wicked and culpable (Acts 4:25-28; Gen. 50:20).

It is sometimes suggested that the human will in Reformed theology is only an illusion. The picture painted is of a God who forces people do what he wants, whether they will to do so or not. This is not the view of the Reformed confessions or the Bible. According to Jesus, only those enabled by the Father can come to him, but they still must come (John 6:37, 44).

Reformed theology denies that our choices can be other than God has decreed and that our will is free to choose what is good, but it does not deny human choice and human willing altogether. The Canons of Dort make clear that divine sovereignty “does not act in people as if they were blocks and stones; nor does it abolish the will and its properties or coerce a reluctant will by force” (III/IV.16).

In short, there is a divine will prior to all human willing, and the will of the unregenerate man is enslaved by sin. At the same time, our wicked choices are really our choices, and they do have real world consequences.

Before Draymond was Draymond…

May 31, 2016

Seven Ways to Improve Your Preaching

I loved the post last week from Mike Kruger, Note to Aspiring Preachers: Here are Seven Key Pitfalls to Avoid. His advice got me thinking about what advice I would give (or have given) to aspiring preachers, or any to preachers for that matter.

I loved the post last week from Mike Kruger, Note to Aspiring Preachers: Here are Seven Key Pitfalls to Avoid. His advice got me thinking about what advice I would give (or have given) to aspiring preachers, or any to preachers for that matter.

Below are seven practical ways we can improve our preaching. And please note: I deliberately use the words “we” and “our,” because I’m thinking of my sermons as much as anyone’s. These suggestions are things I continue to work on as a preacher, sometimes with success and often with less progress than I would like.

1. Make sure your points point to something.

It’s fine to say, “I have three points this morning: Abraham received precious promises. Abraham believed God. Abraham was saved by faith.” It would be better, however, to tell us what holds those points together. Are they three acts in the life of Abraham, or three lessons we can learn, or three reasons Abraham became the father of a great nation? Help orient your listeners so they know what the points are pointing out.

Take time in your preparation to think about these points and how to express them. Normally, the sermon is better if the points are related to the congregation directly. So instead of making the sermon about Abraham, make it about us. “We see in this text three marks of men and women of faith. First, they receive precious promises. Second, they believe those promises. Third, they are saved by those promises.” Of course, in the explanation of those points, you will talk a lot about Abraham, but the congregation should sense you have a word for them, not just a history lesson.

2. Work hard to be simple.

Let me commend to you J.C. Ryle’s address Simplicity in Preaching (recently reprinted in a little booklet by the Banner of Truth). I just read the booklet last week. I was helped a lot (and not a little convicted). Ryle is not arguing for light and fluffy preaching. Rather, he’s insisting on clarity in preaching. Use straightforward syntax. Use simple words, and explain any difficult ones. Employ illustrations. Maintain logical order and progression. And don’t try to do too much.

The best preachers, even when preaching on lofty and heady material, are easy to understand.

3. Don’t just tell the congregation what to feel, make them feel it.

The good preacher is a feeling preacher (see the suggestion #7), but feeling something yourself is no substitute for leading the congregation to feel the same. Don’t just say, “Oh Christ is glorious! He is marvelous! Isn’t his power amazing! We can scarcely fathom his love for us! What a Savior!” Those are all true statements, and the congregation may be encouraged to hear them again. But here’s the difference between a good sermon and a great sermon: A good sermon tells the people all those things. A great sermon opens the word, opens the human heart, and opens the gates of heaven so that by the end of the sermon the people want to exclaim those things.

Obviously, we can’t turn a hard heart into a heart of flesh, but we can labor in our preaching to show instead of only telling.

4. Don’t fall for lazy listing.

This is a besetting sin for many preachers (including this one). Suppose you are preaching on idolatry and say something like this: “We are all idol-makers. We worship false gods that cannot save. They may be gods of money or sex or power or children or career or relationships or comfort or health.” I’ve preached like that dozens of times. It’s not wrong. But a list like that is liable to whiz by most people. For one, it sounds familiar to regular churchgoers. And second, it is too high up the ladder of abstraction to penetrate the human heart.

This is another area where preaching is really hard work. Instead of settling for a list like that, spend another 30 minutes to come up with an example for each of those idols. Or better yet, share an illustration of someone who was tempted to make sex or money (or whatever) into an idol. Help us see the idols in our own lives. Don’t expect the listener to do your work for you.

5. Get down to business sooner.

Granted, some introductions effectively lay out the problem to be considered or appropriately set the stage for the text you are exploring, but too many introductions feel like a sputtering engine or a false start. It would be better to skip the introduction all together (“Thus far the reading of God’s word. I have three points this morning…”) then to take 10 minutes trying to find your groove.

My introductions are often too long and my conclusions are too short. If you have to shortchange one, make it the beginning not the end.

6. Keep pointing back to the text.

There are several goals in expository preaching, but surely one of them is to help the congregation understand the text. This means the preacher must not hover over the text or merely preach on general themes found in the text. He must constantly point people back to specific verses and words and phrases.

After a week of study, we may know the text backward and forward, but the people likely haven’t thought anything about the text until it was just read for them. They aren’t conversant with the ins and outs of the text like you are. Lead them through the passage. If our people can just as easily follow the sermon with their Bible’s closed, then we aren’t getting them in the text like we should.

7. Make sure your heart is kindled first.

You may be able to preach a good sermon without being stirred by the text, but you cannot be a good preacher. Every week, we should learn something from the text, be comforted by the text, be convicted by the text, be challenged, strengthened, or otherwise moved to faith and repentance by the text. Over the course of years and decades we will become empty religious professionals unless we are affected by the things we see in the Bible. The first sermon each week should be the one the Holy Spirit preaches to you in your study.

May 25, 2016

Book Briefs

Here are some of the books I’ve been reading over the past couple months.

Christopher Ash, Zeal Without Burnout (Good Book Company, 2016). A terrific little book you can read in under an hour. Ash’s personal story is fascinating and instructive and his counsel is thoughtful and wise. At some point in ministry, every Christian leader is going to need a book like this.

Christopher Ash, Zeal Without Burnout (Good Book Company, 2016). A terrific little book you can read in under an hour. Ash’s personal story is fascinating and instructive and his counsel is thoughtful and wise. At some point in ministry, every Christian leader is going to need a book like this.

John Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World: The Beginning According to Genesis and Science (Zondervan, 2011). An easy to follow guide to the opening chapters of Genesis from a well-respected scientist and Christian apologist. This wouldn’t be the first Genesis-and-science book I’d recommend, but it’s a fine introduction to the issues and ideas at play.

John Lennox, Seven Days that Divide the World: The Beginning According to Genesis and Science (Zondervan, 2011). An easy to follow guide to the opening chapters of Genesis from a well-respected scientist and Christian apologist. This wouldn’t be the first Genesis-and-science book I’d recommend, but it’s a fine introduction to the issues and ideas at play.

John Piper, A Camaraderie of Confidence: The Fruit of Unfailing Faith in the Lives of Charles Spurgeon, George Muller, and Hudson Taylor (Crossway, 2016). I love Piper’s mini-biographies. I can’t think of one that hasn’t been interesting, edifying, and inspiring. These are no different. Learning (or re-learning) about Spurgeon’s melancholy, Muller’s prayers, and Taylor’s faith will encourage every Christian.

John Piper, A Camaraderie of Confidence: The Fruit of Unfailing Faith in the Lives of Charles Spurgeon, George Muller, and Hudson Taylor (Crossway, 2016). I love Piper’s mini-biographies. I can’t think of one that hasn’t been interesting, edifying, and inspiring. These are no different. Learning (or re-learning) about Spurgeon’s melancholy, Muller’s prayers, and Taylor’s faith will encourage every Christian.

G.K. Beale and Mitchell Kim, God Dwells Among Us: Expanding Eden to the Ends of the Earth (IVP Books, 2014). A solid introduction to the themes of biblical theology. Depending on how familiar you are with Beale and the contours of biblical theology, this could be a groundbreaking work or a nice refresher. We used this as our staff book for the past semester.

G.K. Beale and Mitchell Kim, God Dwells Among Us: Expanding Eden to the Ends of the Earth (IVP Books, 2014). A solid introduction to the themes of biblical theology. Depending on how familiar you are with Beale and the contours of biblical theology, this could be a groundbreaking work or a nice refresher. We used this as our staff book for the past semester.

Craig Hamilton, Wisdom in Leadership: The How and Why of Leading the People You Serve (Matthias Media, 2015). Let’s get the negatives out of the way first. I love Matthias Media, but the cover is cheesy and the book is way too long. This volume is going to reach a smaller audience because it is 78 chapters and 495 pages. Which is a shame, because this is an outstanding book. Hamilton’s thesis is that most Christian leaders are into theology books or leadership books, but rarely both. And that’s a problem. He thinks (1) Christian leadership must be rooted in good theology and (2) theologically-minded pastors cannot ignore principles of good leadership. The result is an extraordinarily practical book that is full of invaluable insight and hard fought common sense. Pick 20 or 30 small chapters and use this book with your staff or your leadership team. I like “Time Management Won’t Help You,” “Praise Publicly,” “Ideas Are Born Ugly,” “Public Fans and Private Critics,” “Choose Your Lieutenants,” “There’s No Point Having a Dog and then Barking Yourself,” and “Why Systems Matter.”

Craig Hamilton, Wisdom in Leadership: The How and Why of Leading the People You Serve (Matthias Media, 2015). Let’s get the negatives out of the way first. I love Matthias Media, but the cover is cheesy and the book is way too long. This volume is going to reach a smaller audience because it is 78 chapters and 495 pages. Which is a shame, because this is an outstanding book. Hamilton’s thesis is that most Christian leaders are into theology books or leadership books, but rarely both. And that’s a problem. He thinks (1) Christian leadership must be rooted in good theology and (2) theologically-minded pastors cannot ignore principles of good leadership. The result is an extraordinarily practical book that is full of invaluable insight and hard fought common sense. Pick 20 or 30 small chapters and use this book with your staff or your leadership team. I like “Time Management Won’t Help You,” “Praise Publicly,” “Ideas Are Born Ugly,” “Public Fans and Private Critics,” “Choose Your Lieutenants,” “There’s No Point Having a Dog and then Barking Yourself,” and “Why Systems Matter.”

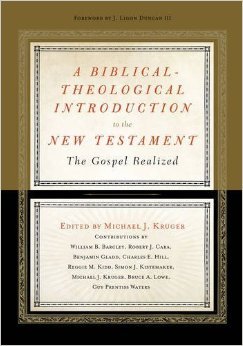

Michael Kruger, ed., A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the New Testament: The Gospel Realized (Crossway, 2016). I was excited to get this book in the mail last week. It looks and feels like a serious book (and it is!). Mike Kruger and Crossway are to be congratulated. Here’s my blurb: “With the right mix of academic integrity and purposeful accessibility, this New Testament introduction will serve time-crunched pastors, ministry-minded students, and church members looking to better understand their Bibles. What makes this new volume unique is the emphasis on examining the theological themes in each book of the New Testament, rather than focusing on arcane debates prompted by liberal scholarship. The result is an insightful and impressive resource, one I will use in my own studies and often recommend to others.”

Michael Kruger, ed., A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the New Testament: The Gospel Realized (Crossway, 2016). I was excited to get this book in the mail last week. It looks and feels like a serious book (and it is!). Mike Kruger and Crossway are to be congratulated. Here’s my blurb: “With the right mix of academic integrity and purposeful accessibility, this New Testament introduction will serve time-crunched pastors, ministry-minded students, and church members looking to better understand their Bibles. What makes this new volume unique is the emphasis on examining the theological themes in each book of the New Testament, rather than focusing on arcane debates prompted by liberal scholarship. The result is an insightful and impressive resource, one I will use in my own studies and often recommend to others.”

May 23, 2016

Don’t Waste Your Summer

It’s almost here. The weather is finally getting warmer (at least here in Michigan). Spirits are up. The days are long. The end of school is nigh. The unofficial beginning of season–Memorial Day weekend–is right around the corner.

It’s almost here. The weather is finally getting warmer (at least here in Michigan). Spirits are up. The days are long. The end of school is nigh. The unofficial beginning of season–Memorial Day weekend–is right around the corner.

Which means in a little over three months we’ll all be moaning, “Where did the summer go? I can’t believe it’s over.” So what can we do over the next hundred days or so to help alleviate that feeling of loss? Or to put it positively, what can we do to make the most of June, July, and August? Here are twenty suggestions.

1. Forget about all the days you’ve missed on your Bible reading plan. Pick up with the schedule this summer and stick with it.

2. Choose 12-15 verses to memorize. Work on one a week.

3. Drive with the windows down, and keep the windows open at night.

4. Take a road trip and sing loudly in the car.

5. Take your kids to a baseball game.

6. Catch fireflies.

7. Play kickball in the backyard.

8. Take a prayer day.

9. Make plans now to watch the Summer Olympics. Go ahead and binge. They only come around every four years.

10. When you’re driving across the country, don’t freak out about stopping at McDonald’s.

11. Keep track of how many hot dogs you eat, and don’t feel bad about any of them.

12. Run/walk/watch a 5k.

13. Go to a parade on Memorial Day; watch fireworks on the Fourth of July.

14. Check Facebook and Twitter and Instagram a lot less.

15. Go outside. Play at the beach. Take a walk. Give thanks to God for his creation.

16. Read a book just for fun. Read another book by someone who’s dead.

17. Stop by the nursing home, the hospital, or the assisted living unit and visit someone who would love to be outside.

18. Go swimming. Don’t worry about how you look (be modest of course!).

19. Invite a friend to church.

20. Buy something from the ice cream truck.

What else would you add to your list?

May 18, 2016

Read Wodehouse and Read the Bible

P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975) is hands down one of the best writers in the English language, ever. He isn’t profound. He isn’t penetrating. His books may not be dissected in lit classes. But his command of vocabulary and syntax is amazing and his humor is, unlikely other humorists, actually very, very funny. There’s nothing like unwinding with a little Jeeves and Wooster after a four hour elder meeting to get the old egg cracking again, what?

P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975) is hands down one of the best writers in the English language, ever. He isn’t profound. He isn’t penetrating. His books may not be dissected in lit classes. But his command of vocabulary and syntax is amazing and his humor is, unlikely other humorists, actually very, very funny. There’s nothing like unwinding with a little Jeeves and Wooster after a four hour elder meeting to get the old egg cracking again, what?

Reading Wodehouse spin tall tales about foppish socialites and an unflappable butler is reminiscent of the best (and cleanest) episodes of Seinfeld. The stories are about nothing, but the characters are so memorable (e.g., the newt loving Gussie Fink-Nottle), the dialogue so perfectly ridiculous (“Hello ugly, what brings you here?”), and the put-downs so ingenious (“It was as if nature had intended to make a gorilla, and had changed its mind at the last moment”) that you can’t help grin, chuckle, and even occasionally cackle.

One reason to read Wodehouse is to admire his use of the Bible. I don’t think he had much of a faith commitment, but his biblical literacy is astounding. For example, take this from the opening pages of The Code of the Woosters, where Bertie is complaining about his rough sleep the night before: “I had been dreaming that some bounder was driving spikes through my head–not just ordinary spikes, as used by Jael the wife of Heber, but red-hot ones.” When’s the last time you’ve hear Jael referenced in a sermon, let alone a novel?

Wodehouse, the product of a more biblically-versed era and, admittedly, a brilliant writer, was constantly making biblical allusions.

Since leaving school he had not devoted much time to the study of the Scriptures, and the stories of the Old Testament had to a great extent passed from his mind. Had this not been so, he would now have been thinking how close was the parallel between his own predicament and that of Moses on the summit of Mount Pisgah. Moses had looked wistfully at a promised land which he was never to reach. He in his mind’s eye was gazing with equal wistfulness at a promised millionaire with whom there seemed no chance of ever talking business.

Here’s a clergyman wondering to Bertie, who is secretly engaged in a gambling ring betting on the length of sermons, if his message might be too long:

You do not think it would be a good thing to cut, to prune? I might, for example, delete the rather exhaustive excursus into the family life of the early Assyrians?

And then there’s this allusion to Job 39:25 (which I had to look up):

He sat up with a jerk. The Biblical horse that said “Ha, ha” among the trumpets could not have displayed more animation.

For good measure, here are few more of my favorites strung together:

There was a death-where-is-thy-sting-fulness about her manner which I found distasteful.

For the first time since the bushes began to pour forth Glossops, Bertram Wooster could be said to have breathed freely. I don’t say that I actually came out from behind the bench, but I did let go of it, and with something of the relief which those three chaps in the Old Testament must have experienced after sliding out of the burning fiery furnace, I even groped tentatively from my cigarette case.

Bertie Wooster won the Scripture-knowledge prize at a kids’ school we were at together, and you know what he’s like. But, of course, Bertie frankly cheated. He succeeded in scrounging that Scripture-knowledge trophy over the heads of better men by means of some of the rawest and most brazen swindling methods ever witnessed even at a school where such things were common. If that man’s pockets, as he entered the examination-room, were not stuffed to bursting point with lists of the kings of Judah–

And last but not least:

He fingered his moustache unhappily. He was feeling now as Elijah would have felt in the wilderness if the ravens had suddenly developed cut-throat business methods.

So what’s the point of all this? Nothing profound, just two things: read Wodehouse and read the Bible–in reverse order of course.

May 16, 2016

A Transgendered Thought Experiment

Rebecca walks into your office distraught and despondent.

Rebecca walks into your office distraught and despondent.

You’ve seen a lot of sad faces as a high school guidance counselor, but even by teenage standards Rebecca looks particularly hopeless. Not wasting any time you pull out a chair, pour her a glass of water, and push a box of tissues her way.

“Thanks,” she sniffles.

“It looks like you’re having a hard day, Rebecca.” You try to sound concerned (which you are) without seeming alarmed (which you might be). “What’s the matter?”

“Well, I’m not sure I want to talk about it.”

“It’s okay. Go ahead. I’m here to help if I can. But I’ll start by just listening.”

“Okay. The thing is, I hate the way I look. I hate my clothes. I hate my body. I hate myself.”

That doesn’t sound good, you think to yourself. “I’m really sorry to hear that, Rebecca. What else can you tell me?”

“Not much really. It’s just that I’m horribly fat. I’ve always felt fat, ever since I was five years old. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t wish for a different body. I’m fat and I’m ugly.”

“But Rebecca,” you start to interrupt, only to have her interrupt right back.

“I know what you’re going to say. You’re going to say I’m fine the way I am. Or you are going to tell me I’m too thin. Or that I’m beautiful. Or some other garbage line. I’ve heard them before. Nothing will change how I feel. I’m fat. That’s why I have to wear these baggy clothes. That’s why I hardly eat anymore. That’s why whenever I do eat I find a bathroom and puke up whatever I just ate. You don’t understand. No one understands. I’m fat. I’ve always been fat. Why won’t anyone let me be what I am?”

At this point there is a pause in the conversation that seems to go on for hours. It lasts only a few seconds, but in those seconds a flood of thoughts enter your mind. You think about trying to get to the bottom of Rebecca’s feelings. You think about scheduling another meeting for tomorrow so you could call her parents and ask her what they’ve been doing to help Rebecca. You think about telling Rebecca what you see with your eyes, that she’s a perfectly normal looking, sweet 15 year old girl. You think about mentioning how concerned you are that it looks like she’s gone from 125 pounds to 95 pounds since the beginning of the school year. You think about presenting the biological facts about a healthy BMI and the importance of daily nutrition. You think about how you want to make sure no one is picking on her and how you’d like her friends to help Rebecca see what she can’t seem to see. Most of all, you think about how you wish Rebecca didn’t feel this way and how you want to do everything in your power to help her understand the way things really are.”

But then another thought enters your mind.

“Rebecca, thank you for sharing. I can’t imagine how hard this has been for you. I just want you to know that I believe you.”

“What?” Rebecca isn’t sure she understands.

“I believe you. I believe everything that you’ve told me. If you tell me you’re fat, I’m not going to stand in the way of you accepting that identity. You’ve suffered too long. You’ve struggled too long. I can see how hard this is for you. But it doesn’t have to be this way. You are fat. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. It’s who you are.”

“Well, I guess that makes sense. No one has ever told me that before. People have always tried to convince me that my body is fine the way it is, even though I desperately wish it were different.”

“I’m really sorry to hear that,” you continue. “A lot of people are prejudiced toward people who identify as overweight. That’s their problem. No one can tell you what’s right or wrong with your body. After all, it’s your body.”

“Wow, that’s not at all what I thought you would say.” Rebecca is genuinely puzzled. “So what do I do now?”

“Great question. First, I’d suggest you act in accordance with how you feel. If you feel fat, then try to eat less. Second, if you continue to feel this way, I’d talk to a doctor about bariatric surgery or some other procedure that will help you get the body you would feel good about. And finally, I’m going to talk to the school board about making some changes around here.”

“Like what?”

“Well, for starters, I want everyone to know it’s okay if you don’t eat much for lunch. Weight is only a social construct. Fat is a feeling, not a fact. And then I want to make sure none of your classmates or teachers try to tell you you’re thin or you’re pretty or you look unwell. That would be really painful to hear.”

“Wow, that sounds really good. For the first time in a long time I feel a little better. Thank you for all these amazing suggestions. I hope more people will learn to accept me like you have.”

As Rebecca walks out the door, your first reaction is to feel a deep sense of satisfaction. She left your office feeling better than when she came. That’s what you like to see. It’s always gratifying to have helped a hurting student. And yet, there’s another thought you can’t quite shake. When you think about her rail thin body, and how desperately she needs food, and how everything must change to conform to her reality, you can’t help but wonder: was this really love?