Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 153

January 13, 2012

Perspicuity and Political Freedom

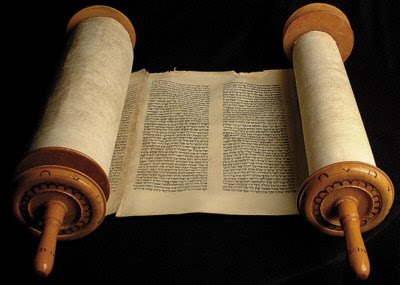

It has been standard Roman Catholic apologetics since the Reformation to criticize the doctrine of the clarity of Scripture on the grounds that the Protestants can't seem to agree on what the Bible actually says. Recently, Christian Smith, noted sociologist and converted Catholic, has argued that this "pervasive interpretive pluralism" is the elephant in the room that squashes the naive biblicism of traditional evangelicalism. There are many things that can, have, and should be said in response to this contention. One could mention the church fathers who saw the same phenomenon in their day without drawing the same conclusions. Or we could turn to almost any Reformed theologian since the Reformation and examine their responses to this common objection. We might open the Scriptures and see how the Bible understands itself. Or we could note that the unity of belief or interpretation that comes from an authoritative magisterium is, under the surface, much less than it seems.

It has been standard Roman Catholic apologetics since the Reformation to criticize the doctrine of the clarity of Scripture on the grounds that the Protestants can't seem to agree on what the Bible actually says. Recently, Christian Smith, noted sociologist and converted Catholic, has argued that this "pervasive interpretive pluralism" is the elephant in the room that squashes the naive biblicism of traditional evangelicalism. There are many things that can, have, and should be said in response to this contention. One could mention the church fathers who saw the same phenomenon in their day without drawing the same conclusions. Or we could turn to almost any Reformed theologian since the Reformation and examine their responses to this common objection. We might open the Scriptures and see how the Bible understands itself. Or we could note that the unity of belief or interpretation that comes from an authoritative magisterium is, under the surface, much less than it seems.

Another approach is to admit that the Protestant doctrines of perspicuity, sola scriptura, and the freedom of the conscience come with dangers, but that these dangers outweigh the alternatives.

Herman Bavinck deftly observes:

The teaching of the perspicuity of Scripture is one of the strongest bulwarks of the Reformation. It also most certainly brings with it its own serious perils. Protestantism has been hopelessly divided by it, and individualism has developed at the expense of the people's sense of community. The freedom to read and to examine Scripture has been and is being grossly abused by all sorts of groups and schools of thought.

On balance, however, the disadvantages do not outweigh the advantages. For the denial of the clarity of Scripture carries with it the subjection of the layperson to the priest, or a person's conscience to the church. The freedom of religion and the human conscience, of the church and theology, stands and falls with the perspicuity of Scripture. It alone is able to maintain the freedom of the Christian; it is the origin and guarantee of religious liberty as well as of our political freedoms.

Even if a freedom that cannot be obtained and enjoyed aside from the dangers of licentiousness and caprice is still always so to be preferred over a tyranny that suppresses liberty. (Reformed Dogmatics 1. 479)

The biblical doctrine of perspicuity can be abused. But a raft of bad interpretations and the sometimes free-for-all of Protestantism is still worth the price of reading the Bible for ourselves according to our God-given (and imperfect) consciences.

January 12, 2012

Thinking Through Church and State

Some good thoughts on the differing purposes of Church and state from James Bannerman:

Some good thoughts on the differing purposes of Church and state from James Bannerman:

In the second place, the state and the Church are essentially distinct in regard to the primary objects for which they were instituted.

The state, or civil government, has been ordained by God for the purpose of promoting and securing, as its primary object, the outward order and good of human society; and that object it is its mission to accomplish wherever it is found, — whether in Christian or heathen lands. Without civil order or government in some shape or other, human society could not exist at all; and as the ordinance of God for all, its direct and immediate aim to aid the cause of humanity as such, without limitation or restriction to humanity as christianized.

On the other hand, the Church of Christ has been instituted by Him for the purpose of advancing and upholding the work of grace on the earth, being limited, in its primary object, to promoting the spiritual interests of the Christian community among which it is found. No doubt there are secondary objects, which both civil government on the one hand, and the Church on the other, are fitted and intended to subserve, in addition to those of a primary kind.

The state, as the ordinance of God, can never be absolved from its allegiance to Him, and can never be exempted from the duty of seeking to advance His glory and to promote His purposes of grace on the earth. And in like manner the Church, in addition to the objects of a spiritual kind which it seeks to accomplish, may be adapted, and is adapted, to further the mere temporal and social wellbeing of society.

But still the grand distinction cannot be overlooked, that marks out the primary objects of the Church and state respectively as separate, and not to be confounded. They are instituted for widely different ends. The one, as founded in nature, was meant primarily to subserve the temporal good of mankind; the other, as founded in grace, was designed primarily to advance their spiritual wellbeing. They may indirectly, and as a secondary duty, fulfill certain ends common to both; they may concur in contemplating certain objects together; but as they differ in their origin, so also they differ entirely in the primary and immediate purpose for which they are respectively established on the earth. (The Church of Christ, Vol. 1, 98-99)

Along similar lines, Guy Waters explains that although Christ reigns over all (Church and state), he does not reign over all in the same way or to the same effect. That is to say, there is a difference between the essential reign of Christ and the mediatorial reign:

Jesus' essential reign belongs to him as Second Person of the Godhead. This reign is unchanging and unchangeable. Jesus' mediatorial reign, however, belongs to him as the Incarnate Son of God, the God-man. This reign he assumed upon his exaltation. This reign is subject to change and may be said to increase or grow. This reign extends to the ends of the earth, but has the church as its particular focus…In other words, in acknowledging Jesus' essential reign, believers particularly confess Jesus, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, to be God over all. In acknowledging Jesus' mediatorial reign, believers particularly confess Jesus to be the risen Lord who purchased them by his own blood. (How Jesus Runs the Church, 33).

The books by Bannerman and Waters are both good. Start with Waters and move on to Bannerman if you want more. I commend them both.

January 11, 2012

Assurance in the Reformed Confessions (2)

Yesterday we looked at the doctrine of assurance in the Canons of Dort (1618-19). Today we turn to the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), specifically Chapter 18 which focuses on "the Assurance of Grace and Salvation."

Yesterday we looked at the doctrine of assurance in the Canons of Dort (1618-19). Today we turn to the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), specifically Chapter 18 which focuses on "the Assurance of Grace and Salvation."

Assurance is a gift available to every true believer. Although it is possible for "hypocrites and other unregenerate men" to deceive themselves with false hope of eternal life, God wants his children to be "certainly assured that they are in the state of grace." This certainty is possible for those who truly believe in the Lord Jesus, love him in sincerity, and endeavor to walk in a good conscience before him (18.1). Notice again the language of "endeavoring" (Dort speaks of "a serious and holy pursuit"). This is both an exhortation and a comfort for the Christian. On the one hand, we ought to strive for good works and a good conscience. On the other hand, we must remember that even endeavoring and pursuing are signs of God's grace in us.

In 18.2, we find the same three grounds of assurance we found in Dort. The "infallible assurance of faith" is "founded upon the divine truth of the promises of salvation, the inward evidence of those graces. . . .[and] the testimony of the Spirit of adoption." On the second point (evidences of grace), the Confessions lists four prooftexts:

2 Peter 1:4-11 which urges us to make our calling and election sure by the diligent effort to grow in godliness and bear spiritual fruit.

1 John 2:3 which testifies that we know we belong to God if we keep his commandments.

1 John 3:14 which assures us that we have passed from death to life because we love our brothers.

2 Cor. 1:12 which speaks of rejoicing in the testimony of a good conscience.

Clearly, the Confession teaches that a transformed life is one sign (though not the cause) of our right standing with God.

Also as in Dort, the Confession allows that true believers may not always experience assurance in this life. Even the regenerate can be shaken and tempted to despair (18.4), for infallible assurance is not part of "the essence of faith" (18.3). We can wound the conscience and grieve the Spirit. God may, for a season, remove the light of his countenance from us (18.4). And yet, it is the duty of everyone to pursue assurance. We do not need "extraordinary revelation," only the "right use of ordinary means" (18.3) This means we should be diligent to make our calling and election sure, that our hearts may be enlarged in peace and joy, in love and thankfulness, in strength and cheerfulness in obedience, which are the proper fruits of assurance (18.3).

Conclusion

The doctrine of assurance in the Canons of Dort is substantially the same as that in the Westminster Confession of Faith. Both enjoin the believer to pursue assurance, while also recognizing that believers don't always have assurance. Both see the doctrine as an incentive to pursue godliness, not as a license to immorality. Both assume that assurance is available to the ordinary believer through ordinary means. And both teach the same three grounds for assurance: the promises of God, the testimony of the Spirit, and evidences of Christ's work in our lives.

If you want to know if you are truly in Christ, forgiven of your sins, and sealed for eternal life, you should rest in the good news of justification by faith alone, listen for the Spirit speaking to your spirit that you are a child of God, and discern (with the help of others) that God is slowly but surely changing you from one degree of glory to the next. Different people at different times under different circumstances will need to hear about all three grounds of assurance. It matters whether you are introspective, doubting, weak in conscience, presumptuous, prone to trust your feelings, or prone to rely on nothing but reason. God motivates us and comforts us in different ways. All three grounds for assurance are Scriptural and given for the cure of souls and the care of God's people.

January 10, 2012

Assurance in the Reformed Confessions (1)

[image error]As evangelical Calvinists and Reformed Christians continue to sort through the complexities of justification, sanctification, law, gospel, and union with Christ, they are also considering what it means to have assurance of salvation. Thankfully, we are not the first persons to wrestle with the topic. The historic Reformed confessions can help us understand what the Bible teaches about assurance.

Let's look at two of these confessions: the Canons of Dort (1618-19) and the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646). We'll tackle one today and one tomorrow.

Assurance in the Canons of Dort

The fifth main point of doctrine in Dort deals with the perseverance (or preservation) of the saints. Because the believer will never be entirely free from sin in this life (5.1) and "blemishes cling to even the best works of God's people" (5.2), we who have been converted could not remain in grace left to our own resources (5.3). That's the bad news. The good news: God is faithful to powerfully preserve his elect to the end (5.3).

This promise of preservation does not mean, however, that true believers will never fall into serious sin (5.4). On the contrary, even believers can commit "monstrous sins" that "greatly offend God." When we sin in such egregious ways, we "sometimes lose the awareness of grace for a time" until we repent and God's fatherly face shines upon us again (5.5). God being for us in Christ in a legal and ultimate sense does not mean he will never frown upon our disobedience. But it does mean that God will always effectively renew us to repentance and bring us to "experience again the grace of reconciled God" (5.7). Therefore, we ought to be assured that true believers "are and always will remain true and living members of the church, and that they have the forgiveness of sins and eternal life" (5.9).

But what are the grounds for this assurance? That's the topic under consideration in Article 10. In asking that question, Dort is not asking about the grounds for our justification or are right standing with God. The question, instead, is about where our assurance of this right standing comes from. Dort asserts, first of all negatively, that "this assurance does not derive from some private revelation beyond or outside the Word" (5.10). That is to say, we don't need a dream or a vision from God or some angel to confirm that we are bound for heaven.

So if not from external revelation, where then does assurance come from? Dort gives three answers:

1. Assurance comes from faith in the promises of God.

2. Assurance comes from the testimony of the Holy Spirit testifying to our spirits that we are children of God.

3. Assurance comes from "a serious and holy pursuit of a clear conscience and of good works" (5.10).

In other words, believers find assurance in the promises of God, the witness of the Spirit, and evidences of Christ's grace in our lives.

A Few Other Points

As precious as assurance is for the believer, it is not itself a requirement of true faith. Believers contend with doubts in this life and do not always experience this full assurance of faith (5.11). But assurance of perseverance is the goal. God wants us to have confidence. This is one of the reasons the perseverance of the saints should never lead to sloth and immorality. When we are confident of the Lord's undying love "it produces a much greater concern to observe carefully the way of the Lord which he prepared in advance" (5.13). In fact, we walk in God's ways "in order that by walking them [we] may maintain the assurance of [our] perseverance" (5.13). Clearly, Dort believes that holiness is not only a ground for assurance, the desire for assurance is itself a motivation unto holiness.

Let me also say a few words about Article 14:

And, just as it has pleased God to begin this work of grace in us by the proclamation of the gospel, so he preserves, continues, and completes his work by the hearing and reading of the gospel, by meditation on it, by its exhortations, threats, and promises, and also by the use of the sacraments.

Notice two things here. First, God causes us to persevere by several means. He makes promises to us, but he also threatens. He works by the hearing of the gospel and by the use of the sacraments. He has not bound himself to one method. Surely, this helps us make sense of the warnings in Hebrews and elsewhere in the New Testament. Threats and exhortations do not undermine perseverance; they help to complete it.

Second, notice the broad way in which Dort understands the gospel (in this context). In being gospel-centered Christians, we meditate on the "exhortations, threats, and promises" of the gospel. In a strict sense we might say that the gospel is only the good news of how we can be saved. But in a wider sense, the gospel encompasses the whole story of salvation, which includes not only gospel promises but also the threats and exhortations inherent in the gospel.

Conclusion

Dort's theology of perseverance and assurance is just as relevant today as it was four hundred years ago. Consider some implications for us:

Believers should not look only to their holy living for assurance, but this should be one place they look. When we see evidences of God's grace in us, we should have confidence that God is at work. And he who begins the good work will be faithful to complete it.

While we must affirm the continuing imperfection of our obedience, we should not so disregard it that we can no longer find real evidences of assuring grace at work.

God's relentless love and the legal standing of our justification do not nullify the real consequence of our sin. We can grieve the Spirit and offend God. His face may turn away from us for a time, until we are led by his grace to repent once again.

Exhortations, threats, and promises are all part of the proclamation of the gospel and instrumental in God's plan to grow us in grace. We should not neglect any of the three in the overall diet of our counseling, preaching, and teaching.

The sacraments are essential in the cause of gospel confidence. They remind our eyes, our hands, our noses, and our mouths of the good news we hear with our ears.

Praise God for old confessions. And praise God for mercies which are new every morning–unto the very end.

Tomorrow: The Westminster Confession of Faith on assurance.

January 9, 2012

Monday Morning Humor

January 7, 2012

Why Lewis Loved the Law

[image error]Many moons ago when I was a little more svelte and the fast twitch muscles twitched a little bit faster, I ran cross country and track. I was either so good or so bad that I think I tried every event in track at least once. I especially liked distance running. Today long distance means running for thirty minutes straight and trying not to empty my inhaler in the process, but back in high school and college I could run for eight or ten or twelve miles and talk the whole way.

One of the things we talked about, I must confess, is how we might trim the day's workout just a wee bit. I was of the Malachi school of running—no harm in cutting a few corners (Mal. 1:6-8, 13). I specialized in straight lines through rounded parking lots. Some of my friends, however, adhered to the Martin Luther "sin boldly" theory of shortcuts. One time they chopped a long run almost in half by cutting through a couple of muck fields. It seemed like a good idea at the time: eliminate the middle portion of the route by taking a left at the celery farm. But unfortunately there are two problems with running through muck. One, the muck sticks to your legs, making your shortcut rather obvious. And two, it's almost impossible to run on muck. In the end, the shortcut proved to quite a long cut and my friends had nothing to show for their crime except for dirty shoes.

It's true in life, as it's true in running around muck fields, that the right way to go is also the best way to go. When God gives us commands he means to help us run the race to completion, not to slow us down. In his Reflections on the Psalms, C.S. Lewis pondered how anyone could "delight" in the law of the Lord. Respect, maybe. Assent, perhaps. But how could anyone find the law so exhilarating? And yet, the more he thought about it, the more Lewis came to understand how the Psalmist's delight made sense. "Their delight in the Law," Lewis observed, "is a delight in having touched firmness; like the pedestrian's delight in feeling the hard road beneath his feet after a false short cut has long entangled him in muddy fields." The law is good because firmness is good. God cares enough to teach his decrees and direct our paths. He reveals his holy character in laying out his holy way. How awful it would be to inhabit this world, have some idea that there is a God, and yet not know what He desires from us. Divine statutes are a gift to us. God gives us law because he loves.

January 6, 2012

Biographies Are Good for the Soul!

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

Read biographies! Would you take the challenge and read some good Christian biographies in this new year? There is such challenge, encouragement, strength, and resolve that comes from reading the lives of those "of whom the world was not worthy" (Heb. 11:38). Let us just take this one small event in one individual life as an example and see what impact it might have upon you.

Jonathan Edwards, though being a great theologian and preacher, was dismissed from his church in Northampton. He moved with his family to Stockbridge and began ministering among the Indians there. For Edwards, this was his golden moment. The conflict of Northampton was mostly behind him and he reveled in the extra time he had to think and write. But then everything changed on September 27, 1757. His son-in-law, Aaron Burr, who had been the president of the new College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton), died. Five days after Burr's death the trustees of the college met and elected Edwards to be their next president.

Edwards received their letter and wrote back to the trustees on October 19th. In the letter he expresses his surprise that they would elect him to be the president of the new college. He then proceeds to list three main objections. First, he had suffered financially from the dismissal at Northampton and his family had just begun to recover. The property he now owned was at Stockbridge and the likelihood of being able to sell it was remote. Second, he felt "unfit" for such an undertaking. His body was suffering from poor health and he said it often led to "a kind of childish weakness and contemptibleness of speech, presence and demeanor; with a disagreeable dullness and stiffness, much unfitting me for conversation, but more specifically for the government of a college." But the third and final point was his greatest objection. He believed that his great service to the Kingdom was found in his writing. And his labor at Stockbridge had finally afforded him the margin and opportunity to concentrate on the larger works he proposed to write for the Church. This was his passion and conviction. He said, "My heart is so much in these studies."

And yet after offering these great objections—family, health, and heart's passion—Edwards relented that if they still desired to have him he would submit the decision to a counsel of fellow ministers. The trustees of the college continued their support of calling Edwards, so Edwards called together his most trusted colleagues and submitted the decision to them. He knew what he wanted to do, but the Church was beckoning him to do something different.

The council met on January 4, 1758 and heard both sides of the issue. And then to a man they quickly decided that Edwards should accept the call to the College of New Jersey. Samuel Hopkins, a disciple of Edwards who was present, wrote what happened next: "When they published their judgment and advice to Mr. Edwards and his people, he appeared uncommonly moved and affected with it, and fell into tears on the occasion; which was very unusual for him, in the presence of others."

Those tears did not stop him. Edwards did not hesitate. Rather, as he said he would, he submitted himself to his brethren. He left later that month and headed to the college and left his "paradise." The first sermon he preached at the college was, "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, and today, and forever" (Heb. 13:8).

January 5, 2012

The Missing Factor in the Justification & Sanctification Discussion

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

We have much to be thankful for in the recent discussion regarding justification and sanctification in the Reformed community. And it appears that this will continue to be a discussion for years ahead. First, I am thankful for the renewed zealousness and commitment to the doctrine of justification. It seems every few decades this doctrine needs to be reconsidered and appreciated due to some assault upon it. Second, I am thankful for the seriousness with which some are looking at the doctrine of sanctification. The Reformed community throughout its history has always maintained a strong teaching on the Christian life and the "working out" of our salvation by the Spirit.

However, one position of the recent discussion is of concern. In some of the current conversation it has been advocated that sanctification purely flows out of our justification.With this tact the Christian is encouraged to merely look back to the reality of their justification in order to grow in sanctification or we are told that sanctification is just "getting used to our justification." But often missing in this pastoral advice or theology is the essential and necessary doctrine of union with Christ. This doctrine also has a long and robust history in the Reformed community. One only needs to think back to Calvin to realize how important this doctrine has been in our circles. Dr. Richard Gaffin in a short article entitled, "Justification and Union with Christ" (which can be found in Theological Guides to Calvin's Institutes edited by David Hall and Peter Lillback) states:

"…for Calvin sanctification as an ongoing, lifelong process follows justification, and in that sense justification is 'prior' to sanctification, and the believer's good works can be seen as the fruits and signs of having been justified. Only those already justified are being sanctified. But this is not the same thing as saying, what Calvin does not say, that justification is the source of sanctification or that justification causes sanctification. That source, that cause is Christ by his Spirit, Christ, in whom, Calvin is clear in this passage, at the moment they are united to him by faith, sinners simultaneously receive a twofold grace (justification and sanctification) and so begins an ongoing process of being sanctified just as they are now also definitively justified" (p.256). (Made bold for our purposes)

Those encouraging us to purely "get used to our justification" or to "look back to our justification" are rightfully concerned about a "works righteousness" mindset among God's people. They are fittingly holding up grace before the Christian's eyes. I am thankful for that concern and share it. In no way should we diminish the centrality of grace and praise God that these voices are reminding the church. They are also rightly concerned that we acknowledge and know the freedom (Romans 6) that attends to the individual who has been justified. How essential it is that we know and dwell in this freedom of the Gospel. There is a true benefit to looking back to our justification. And yet we also want to be careful not to swallow up sanctification in the doctrine of justification (This appears to be the practical outcome for some as any exhortation or application to the Christian life which wanders outside of "look back to your justification" is met with the cry, "Legalism")

But of even greater importance is that in trying to safeguard grace and the Gospel it is possible that some are unknowingly diminishing the center of the Gospel: Christ. It is from our vital union with Him that not only our justification flows, but also our sanctification. It is the doctrine behind both. Calvin states, "For we await salvation from him not because he appears to us afar off, but because he makes us, ingrafted into his body, participants not only in all his benefits but also in himself" (Institutes, 3.2.24). Robert Letham in speaking about Calvin's view of union with Christ as articulated in his commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:24 says, "The first thing in union with Christ is that we are united to Christ himself; his benefits follow from the personal union that we are enabled to share" (Letham, Union with Christ, p. 105).

What are those benefits? They include justification and sanctification. Again Letham states Calvin's view, "Union with Christ is the root of salvation, justification and sanctification included" (Letham, p.110). Calvin is by no means alone in this understanding. The Westminster Assembly clearly articulates this as well in the Westminster Larger Catechism. Question 69 asks, "What is the communion in grace which the members of the invisible church have with Christ?" Answer: "The communion in grace which the members of the invisible church have with Christ, is their partaking of the virtue of his mediation, in their justification, adoption, sanctification, and whatever else, in this life, manifests their union with him."

Union with Christ is the essential doctrine behind not only our justification, but also our sanctification. And that we must never diminish. Justification is a declarative act. But as Calvin said in 3.1.1 of the institutes, "First, we must understand that as long as Christ remains outside of us, and we are separated from him, all that he has suffered and done for the salvation of the human race remains useless and of no value to us." Union with Christ is essential and we must not neglect it in this ongoing conversation about justification and sanctification.

Again, is it helpful to look back to our justification? We must answer, "Absolutely!" But are we to merely look back to our justification? Or is our sanctification purely just "getting used" to our justification? The answer to those questions must be, "No." Does sanctification logically proceed from justification? Yes. But it finds its basis in our union with Christ. As strange as it sounds, because it is clearly not the intention of those advocating such, if we miss the fact that sanctification is a benefit which flows from union with Christ we can end up missing Christ. As Calvin says, "Not only does he cleave to us by an indivisible bond of fellowship, but with a wonderful communion, day by day, he grows more and more into one body with us, until he becomes completely one with us" (Institutes, 3.2.24).

January 4, 2012

An Open Letter to Christian Wives with Unbelieving Husbands

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

Dear Sisters in Christ,

There are people we honor and admire in the Christian life for certain virtues or characteristics which seem to have marked them. Who doesn't admire Martin Luther for his undaunted courage, John Calvin for his doxological mind, David Brainerd for his consistent humility, William Carey for his audacious foresight? But our greatest heroes are often little known and overlooked. And for many of us they are you: faithful and faith-filled wives living with unbelieving husbands. If there are degrees of rewards in heaven you will surely receive a great share. For the Spirit's work in you is evident and has born much fruit. You stand before us each week as a living model of devotion to our Lord.

In some ways we have been shocked by the traits which seem to be readily among you. In other ways we are not shocked at all. The Lord has truly sanctified you in the crucible of life and your holiness glimmers with a shine that surpasses many of our own.

In a day and age where grumbling and complaining is one of the chief sins in the church, it seems to be absent from you. You, like our Lord, "open not your mouth" (Is. 53:7) in complaint.

We look upon your faithfulness and think how much we have to learn. You continue to maintain a godly witness to those around you, a submissive attitude towards your husband, a servant-hearted mindset in the home, a persevering persistence, and a joyous countenance which says, "I can do all things through Him who strengthens me" (Phil. 4:13). We have watched you and continue to be amazed as you raise godly children—we who struggle to do so with two Christian parents in the home.

But it isn't just your example in the home. You continue to willingly and gladly serve in the church and minister to others when your daily life is one of tiring service beyond what many of us know. And in the midst of that service, we often find you to be the most empathetic and compassionate lovers of those who are suffering. We sense no "me" attitude in you, but one of humility and humbleness. Seldom do we find you calling attention to yourselves and you are consistently supportive of others.

Is it an accident that so many of you are marked by these very things? We don't think so. It appears that the Lord has not only blessed your spouse, but us with you. He has used what no doubt is trying and difficult for you, at times or maybe always, to be a blessing to us. You are usually quiet and yet have had a loud impact upon our lives—an impact that is derived by looking at your faithfulness, perseverance, and joy. And as we do so, we are encouraged in the Spirit to "run with endurance the race that is set before us" (Heb. 12:1).

We also want you to know that you are in our prayers. We pray for your continued faithfulness. And we continue to pray for your husband. Though you have been a great example to us in the midst of your current circumstances, we would not desire that you continue in them. We are praying and want to labor with you to see your husband, the groom of your youth, become your brother in Christ. And we continue to trust and hope that your witness and faithfulness will be used by the Lord to that very end. "Wife, how do you know whether you will save your husband?" (1 Cor. 7:16). May it be!

We can't help but think of Paul's words to Philemon and tweak them for our use, "For we have derived much joy and comfort from your love, our sisters, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed through you" (Philemon 1:7). We have been refreshed and filled with joy by your faithful kingdom service. We have noticed. But most importantly, we hope that you know that your eternal bridegroom notices and is pleased.

By His Grace,

Your thankful brothers and sisters in Christ

January 3, 2012

Christian Principles for Realistic Politics

Voting for President of the United States begins today in Iowa. For the next ten months it will be hard to avoid hearing about politics. This is welcome news to political junkies and tiresome for everybody else. But whether you are into politics or not, you should care about the political process. And as Christians we should try to think Christianly about the issues and candidates before us.

Voting for President of the United States begins today in Iowa. For the next ten months it will be hard to avoid hearing about politics. This is welcome news to political junkies and tiresome for everybody else. But whether you are into politics or not, you should care about the political process. And as Christians we should try to think Christianly about the issues and candidates before us.

This can be tricky. On the one hand, I'm concerned that some of us think there is a Christian position on every issue—as if the Bible determines the one and only God-honoring decision regarding rates of taxation or how to respond if Iran closes the Straits of Hormuz. But on the other hand, I fear other Christians are so loathe to seem partisan, or they consider politics so unclean, that they don't dare bring Christian principles to bear on their political thinking. This too is a mistake. You don't have to be a transformationalist or reconstructionist to believe that biblical principles ought to shape the way we look at the world (including politics) and how we understand the way things work.

The Bible is a big book, so there are a lot of things we could say in an effort to piece together a political worldview out of biblical principles. But this is a blog and not a book. So let me take just one doctrinal area and tease out some possible implications.

I believe our most important political considerations grow out a proper understanding of the human person. The more our politicians and political institutions operate according to the way things actually are and the way we actually are the more we will flourish as a nation.

Consider this anthropological principles as you develop political praxis:

1. Man is made in God's image (Gen. 1:26-27). No matter how small or frail or old or impaired every human being has value and dignity. Government should protect human life and punish those who harm it (Rom. 13:4; Gen. 9:6).

2. Man is made to work (Gen. 2:15). We ought to maximize incentives for hard work and remove incentives that encourage laziness (2 Thess. 3:6-12).

3. Part of being human, as opposed to God, is that we are subject to appropriate authorities. This includes subjection to government and the requirement to pay taxes (Rom. 13:1-7).

4. Humans are motivated by self-interest. Jesus understands this when he tells us to love our neighbors as we already love ourselves (Matt. 22:39). Self-interest is not automatically the same as greed or covetousness, which is why Jesus doesn't hesitate to motivate the disciples with the promise of being first or the guarantee of reward (Matt. 6:19-20; Mark 10:29-31). Granted, our self-interest is not always virtuous. The work of the gospel is to teach people how their self-interest (joy) can square with God's interest (glory). But the best policies are those that can harness the power of self-interest for the greater good.

5. Humans are not just consumers on the planet; we are creators too. The physical world is a gift and a tool. We have the ability to spoil, but also the responsibility to subdue (Gen. 1:28).

6. Because of Adam's sin, the world is fallen (Rom. 5:12; 8:18-23). Things are not the way they are supposed to be. Utopia is not possible. Therefore, political decisions must deal with trade-offs, weighing pros and cons of various policies. We cannot eliminate the realities of living in a fallen world (John 12:8), but good policies can help mitigate some of the worst of them.

7. Human nature is bent toward evil (Gen. 6:5; Jer. 17:9). This means we cannot count on the goodwill of others or of other nations, no matter how well-intentioned we may be or how much we may mind our own business. The question is not where war comes from. That is to be expected given our nature. The question is what institutions and policies are most effective at establishing peace.

There is, of course, more we could say about the nature of freedom, the importance of justice, and the right of private property. All three are also crucial biblical themes. But the seven principles above can help us start to make sense of the world, make decisions in the world, and elect politicians who understand the way the world works