Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 149

February 20, 2012

Monday Morning Humor

Caution: a few "goshes" and the like, and one bleeped out word. But very funny. If this guy isn't your dad, then he's your uncle, brother, grandpa, or somebody in your family.

February 18, 2012

Anabaptists for a Historical Adam

In sum, as soon as the Romans fell from a communal [i.e. republican] government to emperors, all their miseries began and remained among them until they became poor serfs, they whose power had previously ruled mightily over the world. I am showing all this here only because all the great lords usually pride themselves on their ancient, preeminent descent from Rome. Yes, they pride themselves on an ancient, heathen descent. And thy do not consider that we are all descended from God, and that nobody is a minute older in his lineage than anyone else, be he king or shepherd, etc. This [concern about descent] is only a poisonous puffing up of a clod of earth [from which Adam was created]. Adam is the father of us all, and we will all, certainly, in one part of us [i.e. the body], fall apart again into rotten pieces of earth. (The Radical Reformation, 114 [emphasis added])

The author of this anonymous tract was once thought to be Andreas Karlstadt, but now it is believed the thought is closer to the views of Thomas Müntzer. No one knows for sure who the author was but it comes out of the "Radical Reformation" and was addressed "To the Assembly of the Common Peasantry which has come together in revolt and insurrection in the high German nation and in many other places." I highlight this paragraph as example of the Christian consensus in previous centuries, across the theological spectrum, that Adam was a real historical person from whom every person was physically descended.

February 17, 2012

More Love To, From, and In Thee

Love is the most excellent way. But it is also an impossible way.

None of us loves like 1 Corinthians 13, at least not fully and constantly. Only One has ever lived in this more excellent way. Only one man has ever loved like this. Only one person will love you like this. "Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love. In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins" (1 John 4:7-10).

Some people say a loving God would not pour out his wrath on his Son for sins he didn't commit. They think they are protecting the love by opposing penal substitutionary atonement. But really they are poaching it. Those who hate propitiation hate what God considers the epitome of love. It's only in the sacrifice of the Son of God that we know what love is really like. "God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us" (Rom. 5:8).

You will never live out your marriage vows or live life to the glory of God unless you learn to love. And you will not learn to love unless you learn to love Jesus. And you will not learn to love Jesus unless you learn to embrace his dying love on the cross for sinners. Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his perfect life for his friends. 1 Corinthians 13 in the flesh.

Jesus is patient and kind. Jesus does not envy or boast. Jesus is not arrogant or rude. Jesus did not insist on his own way, but submitted himself to his Father in heaven. Jesus is not irritable or resentful. Jesus never rejoices at wrong-doing, but always rejoices with the truth. Jesus bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things; and for our salvation, he endured all things. Jesus never fails.

February 16, 2012

But I Don't Hate Anyone

Oh really?

Oh really?

Few husbands think they hate their wives. Few Christians think they hate their fellow church members. Few children think they hate their parents. Few non-Christians think they hate anyone. I've never met a single person who considered himself a thoroughly hateful individual, though I know many who consider themselves quite loving.

But if hate is the opposite of everything love is, where does that leave us?

Hate is impatient and unkind; hate is jealous and proud; hate is arrogant and rude. Hate always insists on doing things its way; hate gets upset over every offense and keeps a close record of every wrong. Hate does not delight to see good things, but rejoices when people screw up or get what's coming to them. Hate complains about anything, is cynical about everything, has no hope for anyone, and puts up with nothing.

Kyrie eleison.

Praise God, he already has (Rom. 5:8; 1 John 4:9-10).

February 15, 2012

Book Briefs

Peter Drucker, The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done (Harper, 2006 [1967]). A steady diet of business management books makes for an unhealthy Christian, but a few good ones every now and then can be quite salutary. This is a good one. Drucker was a legend in leadership consulting. The examples in this book are quite dated, but the advice is still helpful. Drucker illustrates his points effectively and draws from the well of Christian virtue. The chapter on time was especially good.

Peter Drucker, The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done (Harper, 2006 [1967]). A steady diet of business management books makes for an unhealthy Christian, but a few good ones every now and then can be quite salutary. This is a good one. Drucker was a legend in leadership consulting. The examples in this book are quite dated, but the advice is still helpful. Drucker illustrates his points effectively and draws from the well of Christian virtue. The chapter on time was especially good.

Donald Spoto, Reluctant Saint: The Life of Francis of Assisi (Penguin Compass, 2002). It's hard for me to be sure I got to know the real Francis with this book. The author has a decidedly liberal understanding of Christianity (e.g., conversion is defined as "a fundamental experience of the inescapably true orientation of every human being toward the mystery we call God."). Spoto seemed to bend over backward to make Francis a preacher of unconditional love who was against war and hell and lived to empower women and run soup kitchens. Experts on Francis can debate whether Spoto's portrait is accurate. Nevertheless, this is a decent biography of Francis that covers the contours of his life and tries to put his biography in historical perspective. Francis grew up as a selfish, petulant rake. Once he encountered God in an old church, he became a different man. He was not a great thinker and bordered on anti-intellectual. But he inspired thousands with his love for others and self-imposed poverty. Francis was also a lifelong itinerant preacher too, though his message focused on being more like Jesus and doing good to others than on the objective message of the gospel. One can't help but wonder when reading about Francis' crippling doubts and fears at the end of his life and his concern to practice even greater acts of self-denial, if this eccentric, inspiring, caring man understood the gospel of God's free grace in all its glory.

Donald Spoto, Reluctant Saint: The Life of Francis of Assisi (Penguin Compass, 2002). It's hard for me to be sure I got to know the real Francis with this book. The author has a decidedly liberal understanding of Christianity (e.g., conversion is defined as "a fundamental experience of the inescapably true orientation of every human being toward the mystery we call God."). Spoto seemed to bend over backward to make Francis a preacher of unconditional love who was against war and hell and lived to empower women and run soup kitchens. Experts on Francis can debate whether Spoto's portrait is accurate. Nevertheless, this is a decent biography of Francis that covers the contours of his life and tries to put his biography in historical perspective. Francis grew up as a selfish, petulant rake. Once he encountered God in an old church, he became a different man. He was not a great thinker and bordered on anti-intellectual. But he inspired thousands with his love for others and self-imposed poverty. Francis was also a lifelong itinerant preacher too, though his message focused on being more like Jesus and doing good to others than on the objective message of the gospel. One can't help but wonder when reading about Francis' crippling doubts and fears at the end of his life and his concern to practice even greater acts of self-denial, if this eccentric, inspiring, caring man understood the gospel of God's free grace in all its glory.

Mark Chaves, American Religion: Contemporary Trends (Princeton University Press, 2011). An expensive book for a 100 pages of generously spaced texts and charts. The gist: "The religious trends I have documented point to a straightforward general conclusion: no indicator of traditional religious belief or practice is going up. There is much continuity and some decline. . . .If there is a trend, it is toward less religion" (110).

Mark Chaves, American Religion: Contemporary Trends (Princeton University Press, 2011). An expensive book for a 100 pages of generously spaced texts and charts. The gist: "The religious trends I have documented point to a straightforward general conclusion: no indicator of traditional religious belief or practice is going up. There is much continuity and some decline. . . .If there is a trend, it is toward less religion" (110).

Guy Prentiss Waters, How Jesus Runs the Church (P&R, 2011). A very good book with a great bibliography. We need more solid, readable ecclesiology like this. Every church leader can learn from this book. Presbyterians will be most helped, especially those from the PCA.

Guy Prentiss Waters, How Jesus Runs the Church (P&R, 2011). A very good book with a great bibliography. We need more solid, readable ecclesiology like this. Every church leader can learn from this book. Presbyterians will be most helped, especially those from the PCA.

February 14, 2012

The Freedom of the Regulative Principle

[image error]

Even though I grew up in a Reformed church, until seminary I was one of the multitude of Christians who had never heard of the regulative principle. It's not been at the core of my identity. But over the years I've come to appreciate the regulative principle more and more.

Simply put, the regulative principle states that "the acceptable way of worshiping the true God is instituted by himself and so limited by his own revealed will" (WCF 21.1). In other words, corporate worship should be comprised of those elements we can show to be appropriate from the Bible. The regulative principles says, "Let's worship God as he wants to be worshiped." At its worst, this principle leads to constant friction and suspicion between believers. Christians beat each other up trying to discern exactly where the offering should go in the service or precisely which kinds of instruments have scriptural warrant. When we expect the New Testament to give a levitical lay out of the one liturgy that pleases God, we are asking the Bible a question it didn't mean to answer. It is possible for the regulative principle to become a religion unto itself.

But the heart of the regulative principle is not about restriction. It is about freedom.

1. Freedom from cultural captivity. When corporate worship is largely left to our own designs we quickly find ourselves scrambling to keep up with the latest trends. The most important qualities become creativity, relevance, and newness. But of course, over time (not much time these days), what was fresh grows stale. We have to retool in order to capture the next demographic. Or learn to be content with settling in as a Boomer church or Gen X church.

2. Freedom from constant battles over preferences. The regulative principles does not completely eliminate the role of opinion and preference. Even within a conservative Reformed framework, worship leaders may disagree about musical style, transitions, volume, tempo, and many other factors. Conflict over preferences will remain even with the regulative principle. But it should be mitigated. I remember years ago at a different church sitting in a worship planning session where people were really good at coming up with new ideas for the worship service. Too good in fact. We opened one service with the theme song from Cheers. Another service on Labor Day had people come up in their work outfits and talk about what they do. Everyone had an idea that seemed meaningful to them. The regulative principle wouldn't have solved all our problems, but it would have been a nice strainer to catch some well-intentioned, but goofy ideas.

3. Freedom of conscience. Coming out of the Catholic church with its host of extra biblical rituals, newly established Protestant churches had to figure out how to worship in their own way. Some were comfortable keeping many of the elements of the Catholic Mass. Others associated those elements with a false religious system. They didn't want to go back to the mess of rites they left behind, even if by themselves some rites didn't seem all that harmful.

This was the dynamic that made the regulative principle so important. Reformed Christians said in effect, "We don't want to ask our church members to do anything that would violate their consciences." Maybe bowing here or a kiss there could be justified by some in their hearts, but what about those who found it idolatrous? Should they be asked to do something as an act of worship that Scripture never commands and their consciences won't allow? This doesn't mean Christians will like every song or appreciate every musical choice. But at least with the regulative principle we can come to worship knowing that nothing will be asked of us except that which can be shown to be true according to the Word of God.

4. Freedom to be cross cultural. It's unfortunate most people probably think worship according to the regulative principle is the hardest to transport to other cultures. And this may be true if the regulative principle is mistakenly seen to dictate style as well as substance. But at its best, the regulative principle means we have simple services with singing, praying, reading, preaching, and sacraments–the kinds of services whose basic outline can "work" anywhere in the world.

5. Freedom to focus on the center. Usually when talking about corporate worship I don't even bring up the regulative principle. It is unknown to many and scary to others. So I try to get at the same big idea from a different angle. I'll say something like this: "What do we know they did in their Christian worship services in the Bible? We know they sang the Bible. We know that preached the Bible. We know they prayed the Bible. We know they read the Bible. We know they saw the Bible in the sacraments. We don't see dramas or pet blessings or liturgical dance numbers. So why wouldn't we want to focus on everything we know they did in their services? Why try to improve on the elements we know were pleasing to God and practiced in the early church?" In other words, the regulative principle gives us the freedom to unapologetically to go back to basics. And stay there.

February 13, 2012

Monday Morning Humor

Kevins rule.

This is impressive.

If you're interested, you can read more on her one letter solve here.

February 11, 2012

In Praise of Institutions and Organized Religion

Mark Chaves:

Polarization aside, people who do not care about American religious institutions for their own sake still might be concerned that the hollowing out of some traditional religious beliefs and practices–alongside a tentative increase in a generic spirituality–could point to a future in which American religiosity may be less grounded in institutions. Despite continuing high levels of religious belief and some kinds of practice, religious institutions may or may not find ways for people to express their religiosity through face-to-face gatherings and local organizations to the same extent as they have in the past. If half of all the social capital in America–meaning half of all the face-t0-face associational activity, personal philanthropy, and volunteering–happens through religious institutions, the vitality of those institutions influences more than American religious life. Weaker religious institutions would mean a different kind of American civic life. (American Religion, 113)

February 10, 2012

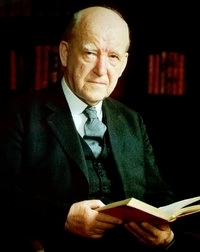

Guest Post: Ligon Duncan on Lloyd-Jones

The new 40th anniversary edition of Preaching and Preachers contains essays from several contemporary preachers, including a piece from Ligon Duncan entitled "Some Things to Look For and Wrestle With." Zondervan has given me permission to reprint that essay below. Ligon's comments serve as a good introduction to the book and are full of wisdom in their own right.

The new 40th anniversary edition of Preaching and Preachers contains essays from several contemporary preachers, including a piece from Ligon Duncan entitled "Some Things to Look For and Wrestle With." Zondervan has given me permission to reprint that essay below. Ligon's comments serve as a good introduction to the book and are full of wisdom in their own right.

*******

I received my first copy of D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones' Preaching and Preachers as a gift from a family in my home church as I was just beginning my studies in seminary. My copy was from the fourteenth printing of the first edition. I had been introduced to Lloyd-Jones as a teenager through his Studies in the Sermon on the Mount (my mother had worn bare a copy of the original two-volume edition) and through the preaching ministry of my boyhood pastor who had been deeply edified by Lloyd-Jones' sermons. Indeed, many of the "Gospel men" in the old Southern Presbyterian Church and in the nascent reforming movements of the early 1970s were profoundly affected by Lloyd-Jones through his preaching at the Pensacola Theological Institute at the McIlwain Presbyterian Church in August of 1969 (as Hurricane Camille was crashing ashore in Mississippi).

I read Lloyd-Jones' preaching in written form before I read Preaching and Preachers. From the first, I was greatly impacted by the power of his sermons, even in printed form. Sentences and paragraphs from these sermons still grip me, utterly. I only heard audio recordings of his messages later, and the medium of his voice added a layer of effect that I had not been able to appreciate before.

Preaching and Preachers is a very different book from his books of sermons. It was given as a series of lectures, and it bears those marks. But it also bears the marks of a man who spent a lifetime preaching and thinking about preaching. Truly, Lloyd-Jones was one of the great preachers of his age. Even in these talks, the fire breaks through. Over and over again. The lecturer on preaching often becomes the preacher.

I encourage you to be on the lookout for some special aspects of this book. The following still arrest my attention when I reread it. I think that when you read this book, several (at least sixteen!) things will strike you.

1. How much the landscape of the church has changed since Lloyd-Jones mused on the background to the decline of preaching in our time. Nevertheless, his discussion is helpful and thought-provoking.

2. His crystal clear and emphatic definition of the work of church and pastor. "The primary task of the Church and of the Christian minister is the preaching of the Word of God." He gives an overview and summary of his biblical case for this. His position is widely denied today but deserves reconsideration.

3. His assertion that great preaching always characterizes the great movements in the history of the Church. Reformation and revival, he says, are always attended by great preachers and great preaching.

4. His reflections on the social application of the gospel in relation to the primacy of preaching. Needless to say, this is a timely discussion for evangelicals again today. In connection with this subject, his argument that "the ultimate justification for asserting the primacy of preaching is theological" will supply you ample food for thought.

5. His emphasis on the importance of gathered, corporate, public worship. "Now the Church is a missionary body," Lloyd-Jones says, "and we must recapture this notion that the whole Church is part of this witness to the Gospel and its truth and its message. It is therefore important that people should come together and listen in companies in the realm of the Church. That has an impact in and of itself." "The very presence of a body of people in itself is a part of the preaching, and these influences begin to act immediately upon anyone who comes into a service."

6. His rejection of what he calls "modern substitutes for preaching" (whether debates or discussion groups or conversation). Preaching, he says, "may be slow work; it often is; it is a long-term policy. But my whole contention is that it works, that it pays, and that it is honoured, and must be, because it is God's own method."

7. His taxonomy of three types of preaching: (1) evangelistic, (2) instructional-experimental (or experiential), and (3) didactic-instructional. Lloyd-Jones believed all three types were necessary, and all three should be explicitly theological. He fruitfully challenges us in this discussion to be theological in our preaching without turning our preaching into lecturing on theology, and he urges that we preach the Gospel, not preach about the Gospel.

8. His proposition that "a sermon should always be expository." Lloyd-Jones defines the term "expository" and gives wise counsel on how to go about preparing such a message. This whole section bears thoughtful engagement.

9. His treatment of the preacher's personality, authority, freedom, exchange, seriousness, liveliness, zeal, concern, warmth, rapport, urgency, persuasiveness, pathos, and power in the act of preaching. This section is solid gold. It is here that he says: "preaching is theology coming through a man who is on fire" and that the chief end of preaching is "to give men and women a sense of God and His presence."

10. His negative assessment of "lay-preaching" and his counsel on what constitutes a call to ministry. Accompanying this section are useful remarks on the training and preparation of preachers and what they need to know to do their work. Along the way, homiletics classes come in for a pounding!

11. His discussion of "the pew" wrongly controlling "the pulpit" is fascinating. We can make all sorts of mistakes when we try too hard to read the congregation. But Lloyd-Jones is remarkably balanced in this: "I would lay it down as being axiomatic that the pew is never to dictate to, or control, the pulpit. This needs to be emphasized at the present time. But having said that, I would emphasize equally that the preacher nevertheless has to assess the condition of those in the pew and to bear that in mind in the preparation and delivery of his message."

12. His warning to preachers not to "assume that all who claim to be Christians, and who think they are Christians, and who are members of the Church, are therefore of necessity Christians" is timely. This warning may be controversial to some, but Lloyd-Jones needs to be heard here.

13. His urging that the need for more than one service on Sunday, for "all the people who attend a church need to be brought under the power of the Gospel." Lloyd-Jones believed the congregational attitude should be, "I want as much of the Word of God, the presence of the Lord, the worship of God as I can get." Surely this bears contemplation in our "one hour a week" era of Christian worship.

14. His wise counsel. "Keep the music in its place. It is handmaiden, a servant, and it must not be allowed to dominate or to control in any sense." This is guidance more needed today than ever before.

15. His encouraging words about "the romance of preaching" may well provide a new hope and spark a new flame in tired preachers' hearts. He reflects on the incomparable feeling of preaching the Word of God to your own people, never knowing when the message is going to unfold in ways you didn't expect even as you preach it, and never knowing when God is going to change someone's life using words that you are privileged to speak for him.

16. His emphasis on the unction or anointing of the Spirit. "What is this? It is the Holy Spirit falling upon the preacher in a special manner. It is an access of power. It is God giving power, and enabling, through the Spirit, to the preacher in order that he may do this work in a manner that lifts it up beyond the efforts and endeavours of man to a position in which the preacher is being used by the Spirit and becomes the channel through whom the Spirit works."

You may argue with Lloyd-Jones from time to time as you read (I do!), but you will always find him a worthy and rewarding conversation partner. More than that, he is a wise mentor. If you are new to the task of preaching, simply engaging with Lloyd-Jones will be a good, shaping, directing exercise in the formation of your practice of preaching. And if you have been long at the task and are now weary in the work of preaching, you may remember some things that you thought you'd long forgotten and feel a renewed passion to proclaim the Gospel and preach the cross and minister the Word.