Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2430

February 4, 2011

Strangely Sensible Barber Licensing

A correspondent sent me a link to a North Carolina state legislator proposing "AN ACT PROVIDING THAT ONLY BARBERS MAY USE THE STRIPED BARBER POLE AS A MEANS OF ADVERTISEMENT."

I don't actually think this is a terrible idea. But what I'd like to see is a scenario in which that's the only legal implication of a barber license. Let the state set up a barber licensing board, let the board devise whatever scheme it deems appropriate, and then give the licensed barbers exclusive right to display the barber pole and proclaim themselves "licensed barbers."

But if some non-barber wants to cut hair, leave him in peace. Then we can see what the real value of the credential is. Personally, I have would have no hesitation whatsoever about checking out an unlicensed barber if a friend or colleague recommended one.

Bloodlands

Timothy Snyder's Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin is a bit hard to take on account of all the killing, but it manages to actually say something new about some of the most covered subjects around.

Two key themes. One is that we misremember the Holocaust because we learn about it from survivors' stories. In concentration camps like Auschwitz many died and many survived, that's why there are survivors. But most of the dead weren't in concentration camps, they were simply killed:

Under German rule, the concentration camps and the death factories operated under different principles. A sentence to the concentration camp Belsen was one thing, a transport to the death factory Bełżec something else. The first meant hunger and labor, but also the likelihood of survival; the second meant immediate and certain death by asphyxiation. This, ironically, is why people remember Belsen and forget Bełżec.

At Bełżec there were 434,508 deaths and maybe two or three survivors. And something similar happened on the Soviet side. We remember the Gulag because people survived the Gulag. Stalin's wholesale massacring of ethnically Polish people living in pre-war Ukraine didn't have enough survivors to be remembered.

There's also this about the curious impulse to exaggerate the degree of suffering even when the true degree of suffering is astounding:

Belarus was the center of the Soviet-Nazi confrontation, and no country endured more hardship under German occupation. Proportionate wartime losses were greater than in Ukraine. Belarus, even more than Poland, suffered social decapitation: first the Soviet NKVD killed the intelligentsia as spies in 1937-1938, then Soviet partisans killed the schoolteachers as German collaborators in 1942-1943. The capital Minsk was all but depopulated by German bombing, the flight of refugees and the hungry, and the Holocaust; and then rebuilt after the war as an eminently Soviet metropolis. Yet even Belarus follows the general trend. Twenty percent of the prewar population of Belarusian territories was killed during the Second World War. Yet young people are taught, and seem to believe, that the figure was not one in five but one in three.

Snyder offers an account of all this with little effort at explicit theorizing.

(Incidentally, I'm trying to read more books and write more about them in part because I think the blogosphere has too many people reading and reacting to the same stuff on the Internet)

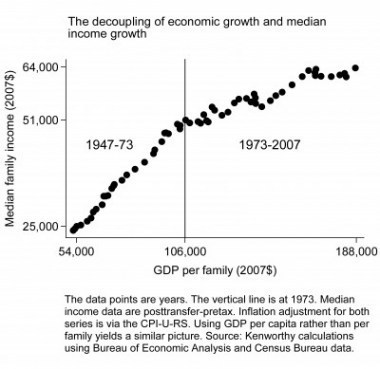

Growth and Decoupling

Lane Kenworthy argues that we haven't just seen a growth slowdown over the past 35 years, we've also seen a decoupling of growth and median living standards. He illustrates it thusly:

What I see when I look at this data is that the "decoupling" went away in the 1990s—the very same period of time when the growth slowdown temporarily went away. So I think the growth problem and the decoupling problem are linked.

Theoretical explanations include an uptick in rent-seeking (FIRE shenanigans, IP shenanigans) that are both anti-growth and pro-inequality, and the fact that tight labor markets disproportionately benefit low-skill workers.

Simple Alternatives To Being Regarded As A Greedy Bastard

This piece on Jamie Dimon's pity party is the latest entry in what's becoming my favorite journalistic genre. You've got a guy, you see, who's making tons of money on Wall Street. But he's not in it for the money. Maybe like Dimon "he sees himself as a financier/statesman." Or maybe he works at Citigroup because he loves the data. But nobody believes him! People think he's just a greedy SOB. So he needs a press strategy to persuade the world.

It's a thorny problem. So here's my idea to help Dimon out. The median household income in Manhattan is about $70,000. For work, I bet Dimon needs more fancy suits and so forth than the typical person, so let's say he needs quadruple the median household income for one of the country's richest and highest-cost jurisdictions. Then maybe we round up to $300,000 a year. That's peanuts compared to what he makes. So give the rest away! You don't even need to bother with charity. Take the income. Pay the taxes. And have your assistant pick a few addresses at random each year and put checks in envelops. If your assistant doesn't want to do it, get in touch with me and I will volunteer my own time to facilitate the semi-random disbursement of unwanted funds.

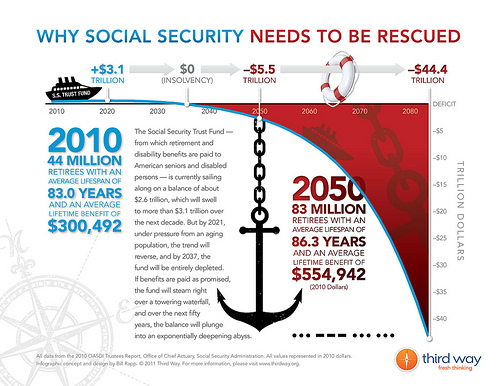

The Social Security Future

Third Way produced a chart here that I can only assume was designed to illustrate the point that it's easy to mislead people if you represent government spending trends over a long time horizon in terms of dollars rather than shares of GDP:

But always a little bit taken aback by the notion of doing 70-year projections of things. 70 years ago it was 1940. Still ahead was Pearl Harbor, World War II, the Cold War, Medicare, civil rights, mass immigration from Mexico, computers, the fall of the Soviet Union, the Internet, etc.

The upshot is that I think it's best to think about this sort of thing in very abstract terms. Currently, the elderly share of the population is expected to rise over time. Consequently, either future elderly individuals need to consumer less relative to the median individual than is currently the case or else taxes on future non-elderly individuals need to be higher or else spending on the non-elderly needs to be lower. Of course, those measures can also operate in various combinations. What's more, different kinds of policy interventions can alter the demographic projections. If you have some kind of view as to what you like out of those abstract ideas, then you can get down to tinkering with exact tax rates and benefit formulae but thinking that you're going to precisely nail decades worth of economic forecasts is bit of a mug's game.

Constitutional Calvinball

Ilya Shapiro is one of those guys who wants the Supreme Court to establish libertarianism as the law of the land. And he thinks that holding a constitutional convention to propose new amendments might bring us closer to that goal. I'm skeptical of that whole agenda in dozens of different ways, but I think his analysis is interesting:

1. An amendments convention is the ultimate guarantor of state sovereignty. History and law support states limiting the convention to specific topics. Delegates to the convention are bound as agents of the states to stay within the scope of the applications that trigger it. And 38 states must ratify whatever the convention generates as a proposed amendment. In short, the states initiate the process, the states control its subject matter, and the states ratify its product.

2. The amendments convention concept is not radical. Washington, Madison, Jefferson and Hamilton all agreed that states should use the Article V process to correct errors in the Constitution and rein in the federal government if it oversteps its bounds. Madison even intervened during the nullification debates of the 1830s to chide the states that they should be invoking the Article V process to regain control over the federal government.

3. The convention will not run away. Any proposed constitutional amendment yielded by the convention requires ratification by 38 states. During the constitutional convention of 1787 the Founders rejected language that would have allowed Article V to establish a foundational convention, substituting language that requires any convention to operate within existing constitutional limits.

4. There is nothing to lose from an amendments convention because no matter which party controls Congress, the status quo is a runaway federal government.

This seems to me to pretty fundamentally misunderstand what it is that a "runaway convention" would be. It's quite true that a convention that adhered to the rules of the Constitution wouldn't run away. But that's nearly a tautology. Ask yourself how we got the Constitution in the first place. Was it by amending the Articles of Confederation? Nope. The Articles were even harder to amend than the current Constitution. But enough people—and sufficiently important ones—wanted to change it, and so they did. That's what a runaway convention would look like. Now obviously that's not going to happen in the short run. But these things do happen, as witnessed by France's transition from 4th Republic to 5th Republic. And though I may be the only one who thinks this, I think it's pretty likely that we'll see a Constitutional Calvinball moment like this at some point during my lifetime. US-style constitutional setups are usually very unstable and the stability of our system was plausibly related to the now-gone tradition of ideologically incoherent parties.

Ask yourself what's more likely: Partisan gridlock leads to major US sovereign default or threat of major US sovereign default leads to institutional changes to eliminate gridlock?

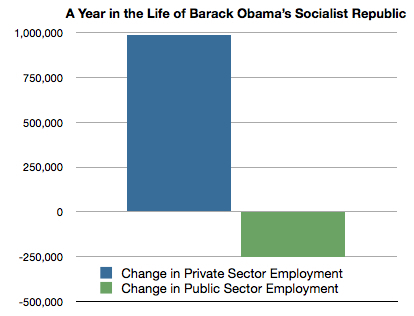

The Continuing Conservative Recovery

With the latest data and revisions in, here's the employment from January 2010 to January 2011:

It would be really nice to see conservatives acknowledge this reality. Conservatives say that we should shift away from public sector employment and toward private sector employment. Which is certainly a view to which they're entitled. But this is what was already happening all last year. Presumably GOP gains in Congress paired with huge GOP gains in state legislatures will accelerate this trend. Which, again, can be deemed a good trend or a bad trend as you like. But this image of a tea party army standing strong against a socialist tide is just made up. In the face of plummeting tax revenues, the public sector has been steadily cutting back and creating a drag on recovery.

Clients and Interests

Some of the conversation around Egypt seems like a good opportunity to point out that there's something very problematic about the discourse of "national interest."

People generally understand that the domestic politics of a large liberal democracy reflect a contending set of interests in which the controlling coalition need have no relationship to the true interests of the nation. America's agriculture policy, for example, reflects the interests of ranchers, corn, soybean, and cotton farmers rather than vegetable growers or food consumers. But this same thing happens in foreign policy.

For example, one thing you tended to see during the Cold War was that the US and the USSR both cruised around the developing world basically trying to line up as many client states as possible. These countries, being poor, were almost always net economic drains on their superpower sponsor. In essence, the Soviet and American governments were competing to bribe local political elites. In this context, Egypt becoming a country whose elites were on the Soviet dole was a "win" for Communism whereas its decision to switch and start accepting American bribes was a win for liberal democracy.

This kind of thinking can sometimes reflect an accurate assessment of what's good for the country. But it's also redolent with interest group capture. When the USA assembles a large coalition of allies that is, among other things, a large coalition of customers for American defense contractors. What's more, the allies then often need defending, both in terms of military bases and general expeditionary capabilities. So we have a controlling domestic political coalition that's defined our "interests" in the Middle East as consisting of collecting a large and diversified portfolio of local allied regimes who we then directly and indirectly subsidize. But the proposition that this reflects the real interests of the American population is contestable. The connection to real interests is that the price of gasoline is very important to the welfare of the average American household, and that Middle Eastern politics are important to the price of gasoline. But I'm not sure Middle Eastern politics really are all that important to the price of gasoline over the long run and I'm quite certain that the past 30 years worth of American policy in the region don't represent a cost-effective way of coping with the economic risks of oil price instability.

Adventures in Occupational Licensing: North Carolina Traffic Engineering Edition

I'm assuming this effort to deploy occupational licensing law to harras someone isn't going to hold up, but maybe I'm wrong:

After an engineering consultant hired by the city said that the signals were not needed, Cox and the North Raleigh Coalition of Homeowners' Associations responded with a sophisticated analysis of their own.

The eight-page document with maps, diagrams and traffic projections was offered to buttress their contention that signals will be needed at the Falls of Neuse at Coolmore Drive intersection and where the road meets Tabriz Point / Lake Villa Way.

It did not persuade Kevin Lacy, chief traffic engineer for the state DOT, to change his mind about the project. Instead, Lacy called on a state licensing agency, the N.C. Board of Examiners for Engineers and Surveyors, to investigate Cox.

As ever, it's important to distinguish this from a law against fraud. Obviously people shouldn't be allowed to misstate their credentials, be they engineering credentials or whatever. But nobody's alleging fraud here:

Cox has not been accused of claiming that he is an engineer. But Lacy says he filed the complaint because the report "appears to be engineering-level work" by someone who is not licensed as a professional engineer.

Essentially the work is too good for a non-engineer to be allowed to produce.

A Strange Employment Work

Weak jobs numbers but a big fall in the unemployment rate. At first glance I thought that was people dropping out of the labor force, but it seems instead to be the conjunction of two different things. One is upward revisions of the last couple of months' worth of jobs data. The other is a downward revision to the baseline estimate of how many people there are. Basically, more people had jobs a month ago than we thought had been the case, and also there were fewer unemployed people than we thought had been the case.

The upshot is that the new data looks a lot better than the old data. But the new data doesn't say the situation improved dramatically over the past month, it merely says that last month's take on the situation was too pessimistic.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers