Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2351

April 17, 2011

The Information

I read James Gleick's The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood on my Kindle ap for iPad so consequently working my way through it I had no intuitive sense of when I was approaching the end of the main narrative and the beginning of the footnotes. When I reached the end, I was surprised and saddened. That five percent reflects the fact that the execution of the conclusion is a bit off and 95 percent reflects the fact that it's a great book I was disappointed to see end. The basic aim, fully achieved, is to situate the miraculous PC revolution of the past thirty years to a longer series of ongoing revolutions in the sphere of "information" dating back to the telephone, the telegraph, and beyond. Sporadic narrative tendrils bring you to ancient times and pre-colonization Africa, but the core focus is on the post-Morse development of modern means of storing and transmitting information and how it is we came to understand that there is such a thing.

As a bad speller, I can't help but like this glimpse at the good old days before the standardization of English spelling:

In fact, few had any concept of "spelling"—the idea that each word, when written, should take a particular predetermined form of letters. The word cony (rabbit) appeared variously as conny, conye, conie, connie, coni, cuny, cunny, and cunnie in a single 1591 pamphlet. Others spelled it differently. And for that matter Cawdrey himself, on the title page of his book for "teaching the true writing," wrote wordes in one sentence and words in the next.

For a critical and overly literal assessment, see Geoffrey Nunberg in The New York Times. If you like good books on technical and historical subjects, read the book.

Coal Is Cheap Because Of The Massive Unpriced Externalities

Paul R. Epstein, et. al., "Full cost accounting for the life cycle of coal"

Each stage in the life cycle of coal—extraction, transport, processing, and combustion—generates a waste stream and carries multiple hazards for health and the environment. These costs are external to the coal industry and are thus often considered "externalities." We estimate that the life cycle effects of coal and the waste stream generated are costing the U.S. public a third to over one-half of a trillion dollars annually. Many of these so-called externalities are, moreover, cumulative. Accounting for the damages conservatively doubles to triples the price of electricity from coal per kWh generated, making wind, solar, and other forms of nonfossil fuel power generation, along with investments in efficiency and electricity conservation methods, economically competitive. We focus on Appalachia, though coal is mined in other regions of the United States and is burned throughout the world.

Coal-fired electricity is cheap for roughly the same reason that pulling a dine and dash at a fancy restaurant is a cheap way to get a nice dinner.

Spending Caps As A Percent Of GDP

There's a lot not to like about the idea of "spending caps." How large a share of its economy a country puts into the public sector is an important indicator over the medium-term. But attempting to fix that at a particular number on a year-to-year basis carries two problems.

One is that it's strongly pro-cyclical. A country using sound budgetary practices will let the public sector share of its economy shrink a bit if there's some kind of economic boom. That's what we saw in the second half of the 1990s. The rapid expansion of the information technology industry and the adoption of productivity enhancing methods in the retail sector meant that the public sector (dominated by defense, health, and education) shrank a bit relative to the rest. Conversely, if a recession hits that doesn't magically decrease demand for health care services. A "capped" country is going to be reducing spending at the worst possible time and then will try to make it up with problematic rapid runups in spending during booms.

The second is that though the spending share of GDP is an important indicator, it's hardly the only indicator that matters. Governments can get things done through regulatory mandates or tax loopholes as well as by spending money. For example, in the United States we have very little direct expenditure on housing, but it's hardly the case that the housing sector is un-affected by public policy. Housing is, instead, the target of a major tax break, the subject of intense regulation, and the beneficiary of the implicit guarantees of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. If you arbitrarily cap government spending, that's not going to eliminate public desire to achieve certain ends. Over the long run, it's going to end up channeling all that activity into regulation and tax breaks.

April 16, 2011

A Dynamic Concentration Approach To Controlling Drug Violence In Mexico

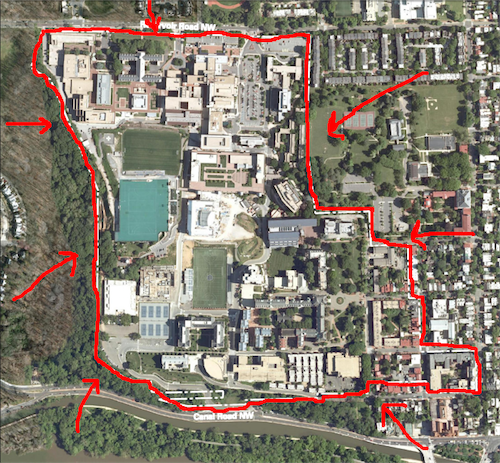

(my photo available under cc license)

Mark Kleiman on what Mexico can do to better control drug-related violence:

Mexico should, after a public and transparent process, designate one of its dealing organizations as the most violent of the group, and Mexican and U.S. enforcement efforts should focus on destroying that organization. Once that group has been dismantled – not hard, in a competitive market – the process should be run again, with all the remaining organizations told that finishing first in the violence race will lead to destruction. If it worked, this process would force a "race to the bottom" in violence; in effect, each organization's drug-dealing revenues would be held hostage to its self-restraint when it comes to gunfire.

I certainly agree that something along these lines is the right way to deal with the crime and violence associated with hard drugs. The idea that a city is going to eradicate the buying and selling of cocaine and heroin from its borders is preposterous. What you want to do is make the dominant business strategy for a vendor of hard drugs be something like "don't kill anyone and don't be a nuisance." You find the peg that's stick out highest on the disruptiveness chart, and you whack it down.

But this all relies on what Mexico can't necessarily count on—a well-functioning public sector that can be relied on to engage in "a public and transparent process" in a reasonable way.

Neighbors Vs Universities

Lydia DePillis reports on neighborhoods mobilizing against universities:

Most of the universities have some group that resists their expansion, whether explicitly (like AU's Neighbors for a Livable Community) or in their capacities as citizens associations. Now, for the first time, activists from around the city are coming together to push the Wilson Building for laws that "protect communities" against "aggressive university growth."

The District-Wide Coalition of University Neighborhoods has a six-member organizing committee of people from the American, Georgetown, Howard, Catholic, and George Washington areas, and has so far been endorsed by the Foggy Bottom Association, Citizens Association of Georgetown, and Burleith Citizens Association. They plan to incorporate as a non-profit and advocate for stricter caps on enrollment, containing new student housing, and anything else that would keep "disruptive" students under wraps.

As I've said before, I think it would be smart for economics teachers to try to draw more of their examples of government intervention into the marketplace from this sort of domain. Maybe it's a good idea for rich, politically powerful households who live near rich, politically powerful universities to use the power of the state to restrict universities from deploying their property as they see fit or maybe it's a bad idea. But like all interventions into the marketplace, these interventions create some distortions. And this kind of issue is a much more typical and realistic example of a deviation from the abstract ideal of a free market. It's not particularly "ideological" it's just people who want to use the political system to get their way.

The Spending Debate

Richard Stevenson writes that "What is under way now is the most fundamental reassessment of the size and role of government — of the balance between personal responsibility and private markets on the one hand and public responsibility and social welfare on the other — at least since Ronald Reagan and perhaps since F.D.R."

I sort of doubt this on a number of levels, including the fact that there's a lot of mismatch between our historical memory of these events and their reality. Consider the actual federal spending trends of the past forty years:

Nothing about this exactly screams "Reagan Revolution" to me. Federal spending was consistently above the long-term average in the Reagan years, in stark contrast to the small government agenda of Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. Of course a lot of this is national defense. But spending is spending, and traditionally the defense channel is one of the main ways we do social welfare policy in the United States. See, for example, the GI Bill. And even though we remember Social Security as a key element of the New Deal welfare state, the program as we know it was really created in the 1950s rather than the 1930s.

I think the right way to think about the current debate is this. We have a fairly settled view in the United States that one important function of the government is taking care of elderly people. We also have a fairly settled view in the United States that one important function of the government is ensuring that people have health insurance. We also have a fairly settled view in the United States that we like being an unusually low tax country. We also also have a fairly settled view in the United States that we want to maintain a uniquely expensive posture of global military hegemony. These are straightforwardly incompatible goals. Large, regionally significant states such as China, India, Brazil, and Nigeria are growing faster than we are putting pressure on military hegemonism. The share of the population composed of elderly people is rising. And the productivity of the health care sector is increasing more slowly than the productivity of the economy as a whole. This leaves us with a lot of adjusting to do.

The essence of the problem is that what people want is the status quo, but the status quo is untenable. In a healthy political system featuring bipartisanship by alternation, both parties would put forward visions of fairly small deviations from the status quo and they would take turns implementing those deviations. The net impact over the course of the years would be quite large, and the weighting of the changes would depend on what proves workable, what proves popular, and the vicissitudes of electoral politics. Instead, we have a political system that counts on this problem being solved via some form of "grand bargain." That turns various proposals into game theoretical exercises and creates a strange bargaining dynamic that empowers extreme voices.

The State Level War On The Environment

A frightening Leslie Kaufman report indicates that Maine's new governor thinks the state suffers from an excess of natural beauty:

Weeks after he was sworn in as governor of Maine, Paul LePage, a Tea Party favorite, announced a 63-point plan to cut environmental regulations, including opening three million acres of the North Woods for development and suspending a law meant to monitor toxic chemicals that could be found in children's products.

We also learn that Chris Christie thinks "the Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act, which preserves more than 800,000 acres of open land that supplies drinking water to more than half of New Jersey's residents, is an infringement on property rights." And, indeed, it does sound like that's a bit of an infringement on property rights. With the purpose, it seems, being to preserve drinking water. Is that the only infringement of property rights that exists in the entire state of New Jersey? Or would it be possible to tackle the state's anti-density zoning rules rather than its water protection ones?

Finland's Selective Teacher Training Programs

I don't agree with everything in Time's take on Finland's education policy successes but I think this correctly grasps the most important thing:

In 2008, the latest year for which figures are available, 1,258 undergrads applied for training to become elementary-school teachers. Only 123, or 9.8%, were accepted into the five-year teaching program. That's typical. There's another thing: in Finland, every teacher is required to have a master's degree. (The Finns call this a master's in kasvatus, which is the same word they use for a mother bringing up her child.) Annual salaries range from about $40,000 to $60,000, and teachers work 190 days a year.

"It's very expensive to educate all of our teachers in five-year programs, but it helps make our teachers highly respected and appreciated," says Jari Lavonen, head of the department of teacher education at the University of Helsinki.

I don't think there's a ton of evidence that the existence of a five-year program, per se, is doing much work here. Many American teachers have master's degrees and there's very little evidence that they do any better than our BA-wielding teachers. The key point as far as I can tell is simply that these programs are very selective. Lots of people want to be teachers, so it's hard to get into the programs, so getting into the program makes you seem prestigious, which makes applying to be a teacher desirable, etc., etc., etc. It's a self-sustaining cycle. Teach For America has some of this quality where people apply because it's prestigious and it's prestigious because it's selective and it's selective because a lot of people apply, and one's generally hears that this can't be scaled up. But in Finland it more or less is.

NBA Playoff Predictions

Round one in the East is easy—top seed wins everything. And actually the whole East is seeded correctly, Chicago and Miami will win in the second round, and then I think Chicago beats Miami to head to the finals.

In the West round one, I think Portland can upset the choketastic Mavericks and otherwise the top seeds get it, though Denver will give OKC a run for its money. Oklahoma City upsets San Antonio and LA beats Portland. LA beats OKC in the Conference Finals, then loses to Chicago in the end.

April 15, 2011

Endgame

Watch the way the world goes:

— Is India actually growing faster than China now?

— What it takes to get an abortion in South Dakota.

— Stuff Political Scientists Like: original data.

— I like the comments here.

— House votes to eliminate Medicare and deregulate the banking sector.

For tax day, it's The Offspring's "Pay The Man" (I'll admit, this song sucks…still, it fits thematically).

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers