Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2345

April 20, 2011

Will Ferrell's Favorite Writer-Director Wants More Protest Songs!

By Alyssa Rosenberg

Adam McKay, the man who gave us the satirical masterpiece Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy and stealth financial meltdown rage comedy The Other Guys, has decided that in addition to movies about angry boy-men, what America really needs more of is protest songs, particularly ones in the public domain so lots of people can cover them. He's even set up a website and written a song on the subject himself! McKay's not the only person to jump on the idea that we need a new wave of iconic music to galvanize liberal dissent. The Mountain Goats' John Darnielle called for covers of protest songs on Twitter during the showdown in Wisconsin and contributed a cover of Billy Bragg's "There Is Power In a Union" to the cause:

Power In A Union from JD on Vimeo.

And Audioslave's Tom Morello played a concert in Wisconsin in February.

It's not like there's anything new about the attempt to link politics and music, or to find the perfect, galvanizing song for a campaign or cause. We will be cracking up over presidential contenders' attempts to find pop middle ground in their theme songs as long as there are politicians. But I'm interested in the sense that there ought to be a musical movement to match the progressive political one, some school of people who are cranking out contemporary "Ay Carmela"s:

and "The Times They Are a-Changin"s:

I don't know why we're not getting those sort of immortal songs spontaneously. Maybe it's the corporatization of our music industry, which doesn't exactly make it easy for deeply engaged folk songs to bubble up the charts; or the fact that we don't have a moment of musical innovation that's motivated by and intertwined with politics; or the fact that if you deliberately go out and try to write a protest classic, you're like to end up with something self-conscious and clunky. Or maybe it's just that our popular music is in a sort of disposable moment, and it's not clear if any songs (other than maybe ones by Kanye?) are going to be truly indelible. But I don't know that we're going to get great new politicized music either by chance or by dint of effort.

Jeff Green's Problem Is A Lack Of Basketball Skill, Not Adjusting To A Role

Many sound points in John Hollinger's latest column but this makes me scratch my head:

The bench continues to struggle despite what appears to be solid individual talent; for some reason Jeff Green, Delonte West and Nenad Krstic haven't clicked with their roles.

As previously reported on the Yglesias Blog, the glaring fall in Boston's decision to acquire Jeff Green is that Jeff Green is a bad basketball player. Nenad Krstic is also a bad basketball player, though I had previously thought this was so widely known that it didn't need to be emphasized. Green continues to click in the role of a poor rebounder who shoots with low efficiency and plays defense badly. I'm not sure why it required a move to Boston for people to see that he's not good, but the low quality of his play is very consistent.

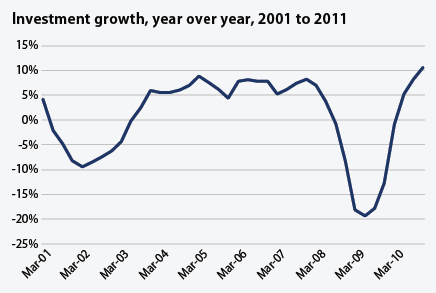

The Return Of Business Investment

Christian Weller's latest economic snapshot shows that one key indicator of recovery—business investment—seems to be with us:

What would be nice would be to see that matched by an uptick in residential investment. We've actually gotten to the point where there's a shortage of houses in America so you might expect to see this around the corner. The problem is that financing is still all snarled up with foreclosures rising and many homeowners underwater. This seems likely to keep a lid on things. Meanwhile, high oil prices are going to be a big drag on growth.

Tax Code Efficiency Matters

Ernie Tedeschi thinks he's disagreeing with me about taxes, but in fact I completely agree with him—the design of a tax system matters a lot for economic growth. In particular, if you have a tax code that combines relatively high marginal rates with a large number of deductions that creates a large distortion in your economy.

I'm not trying to say that taxes don't matter. I think taxes matter a lot. But they matter in specific ways for specific things, and I don't think that the overall level of taxation matters nearly as much as American political conversations tend to indicate. Sensibly designed tax codes can raise tons and tons of revenue without crippling growth the way American conservatives say they will. At the same time, I think conservatives and liberals both (but in different ways) understate the extent to which making policy through tax deductions is a big deal.

Paul Ryan's Plan To Deepen The Recession

Representative Paul Ryan (R-WI) is best known as a guy who wants lower taxes on the rich, steep cuts in Medicaid, and the privatization of Medicare. But he's said that "monetary policy was always my first love" and he does a brisk side business as a hard money deflationist. My colleague Scott Keyes was at a Ryan town hall in Elkhorn, Wisconsin yesterday where he fielded a question about the Fed's "quantitative easing" efforts and reiterated his commitment to fearmongering about inflation and keeping American unemployment high:

CONSTITUENT: Our dollar is getting so damn debased. That's the price of oil. When the dollar goes down, oil goes up. What are you going to do about Bernanke? Now, I have to say, I didn't watch the hearing with Bernanke two months ago. What are you going to do with Bernanke? Because that's the other side of this coin. We're getting cheap dollars. I understand the debt is a big problem, but these cheap dollars are hurting the hell out of us. It monetizes our debt, but it says, "okay, we're going to inflation it." That's just not right. And it's hurting the hell out of the old folks.

RYAN: I totally agree with that. Look, there is nothing more insidious, more undermining that a government can do to its citizens than to debase its currency. If you're living on a fixed income, if your savings are denominated in dollars, which all of ours are, and you already retired, you're the person that's going to get hurt the worst if we have an inflation crisis. And I totally agree with that. I think QE2 has been a mistake. You can argue that it originally worked to keep interest rates down, but at what expense? What we have is the Federal Reserve creating so much more money, and when you create so much more money, you inevitably end up with inflation. Now, they think they've got this all figured out and that they can drive the car between the pilons going at 110 mph. What I'm basically saying is they think they can mop all this extra money up before inflation gets out of control. We're in an uncharted territory. So when Ben Bernanke winds down QE2, Quantitative Easing 2, or the money printing, at the end of June like he says, it's going to be interesting to see what happens. Quite frankly, I don't know.

An accurate response to the question would have started with the observation that monetary-induced increases in the price of oil ought to be visible across all goods and services. What we've seen is an increase in the price of oil relative to things that aren't oil. Monetary policy can't make that happen.

But ignorance and misinformation aside, I'm puzzled by the lack of imagination Ryan displays with his repeated insistence that currency debasement is the worst thing a country can do to its citizens. The current government of the People's Republic of China has mismanaged its monetary policy and consequently China is experiencing a moderate burst of inflation. In the 1950s, the government of the People's Republic of China engineered the Great Leap Forward and tens of millions of people died in a famine.

One window into Ryan's overestimation of inflation's perniciousness comes from his reference to its impact on senior citizens. The thing about this is that most seniors rely on Social Security for the majority of their income and Social Security benefits are indexed to inflation. So it's really only the interests of a minority of rich retirees whose concerns Ryan is addressing here. And the flipside, of course, is that tight monetary policy controls inflation by keeping unemployment high, thus preventing workers from seeing their wages go up. Ryan wants you to believe that adopting his Medicare privatization plan will lead to an employment boom in the United States, but there's no way for this to happen unless it spurs looser money. Perhaps Ryan is confused about this, or perhaps his view is that the Fed should keep its boot on the country's neck as a way of extorting budget cuts. Either way, it would be enlightening to see the Ryan-loving DC press corps push him a bit more on monetary issues.

Urbanism And Water Scarcity

When SA sent me a link to an article about a large "new urbanist" development planned for the suburbs of Albuquerque, I was instinctively skeptical. I like cities, personally, but I try not to let that cloud my judgment to much. Historical urbanism was driven by transportation technology (harbors, rail lines, but no cars) and present-day urbanism should be driven by scarcity of land but unless Albuquerque has changed dramatically since I was there three years ago they're not exactly running out of space in New Mexico.

But this points perhaps in another direction:

Like other desert boomtowns, Albuquerque's loosely planned sprawl is on a collision course with its finite water supply. Mesa del Sol will have an extremely efficient water system, and its dense, mixed-use design could reduce the need for more development on the city's west side, where suburbs have consumed huge tracts of once-wild desert.

I'm not at all familiar with the details of western water management issues, but in general water rather than space is the scarce commodity in that region. If it's the case that urbanism is a way of economizing on water, then it might have a promising future there. At the same time, we really really really really really really don't have a free market in water in this country, especially in arid parts of the west. Consequently, water-related development decisions are rarely driven by straightforward considerations of trying to allocate a scarce resource efficiently.

Network Effects Drive The Success Of Bicycle Socialism

(cc photo by ericgbrown)

Washington, DC has a bike sharing program called Capital Bikeshare. If you pay an annual membership fee, you can take the bikes out for short-terms at no marginal cost. A longer ride costs you a bit, and non-members can rent bikes on the spot for a fee. Recently they offered a big discount via Living Social and got a ton of new members. DCist wondered at the time if the membership surge would outstrip capacity but now they're feeling sanguine:

District Department of Transportation spokesperson John Lisle wasn't too worried about it at the time, though, telling DCist that DDOT had "a plan to expand the system to help meet that demand" which included new stations in Arlington and D.C., some of which would "be installed before the end of the month." He wasn't kidding — during a press conference this morning, Mayor Vince Gray and transportation officials announced plans to install for several new stations around the District, including one located right in front of city hall.

This kind of sharing system has the interesting property that if the ratio of members to stations stays constant, then as the number of members increases the value of a membership goes up. That's because from the perspective of an individual member, a low member:bike ratio has value but so does a high density of stations. If 50 percent of DC residents were Capital Bikeshare members, then maintaining the current number of stations would require there to be stations all over the place. And that would make the whole system much more useful.

That's not going to happen, of course, but it's an indication of the kind of benefits that higher levels of population density can have for a city as well as a vindication of the idea of jumpstarting the program with some discounts. This also illustrates an example of a service that's well-provided by a monopolist. Having multiple competing firms would fragment the network and reduce value.

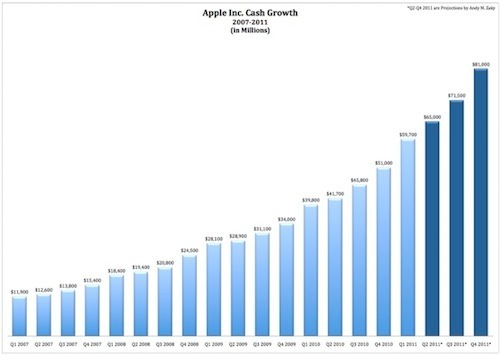

Apple's Cash And The Corporate Commons

The standard assumption is that if I firm is earning an extraordinary level of profits, that will draw new entrants to compete with it and the profit margins will decline. But for years now Apple has been able to maintain extremely high margins in its various businesses and consequently it sits upon a giant and growing horde of cash:

Fortune's Andy Zaky argues that when you keep this in mind that means that Apple's share prices reflect an irrationally low estimate of its "enterprise value." An alternative interpretation is that they reflect a market assumption that this cash will eventually be wasted.

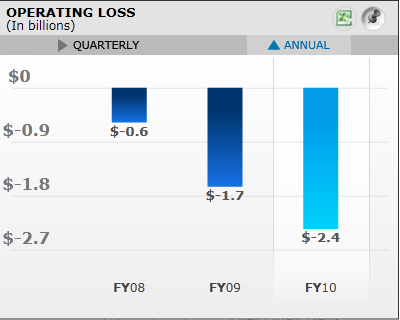

Microsoft, for example, seems to have decided that the best thing to do with its hugely profitable OS and Office businesses is lose stupendous sums of money trying to compete with Google via a stunningly profit-negative Online Services division:

Karl Smith calls this "burning the corporate commons" and it's a big impact on our economy. Not that firms never successfully launch new product lines. Microsoft's Online Services Division may lose tons of money, but the XBox is a successful product, and obviously Apple's decision to reinvest iPod profits into iPhone and then iPad development has paid off well. But firms that reinvest profits in smart ways only end up with what Apple has—an even bigger wad of cash to eventually waste.

I don't really think the impulse to burn the commons can be eradicated in a sustainable way. The fact that you need to be irrationally overconfident in your own business acumen to become a top executive at a major firm is only slightly paradoxical. But social norms around the wastage seem to change over time. Back in the proverbial day AT&T and IBM wasted a lot of money on funding basic scientific research, while today's firms seem to prefer to waste money by entering new product markets.

Public Opinion: Totally Gay, and Getting Gayer

Nate Silver rolls out some regression smoothing:

Two main points here. One is that it may be time for Barack Obama to consider a flip-flop on this subject. In changing its legal theory on the Defense of Marriage Act the administration decided that classification by sexual orientation requires "heightened scrutiny" under the 14th Amendment and that DOMA doesn't pass the test. To my eye, that implies that all marriage discrimination legislation requires heightened scrutiny and makes it hard for me to see how any form of discrimination can pass the test. But I don't think this issue has been faced squarely by the administration yet.

The other is that if Justice Kennedy and the four other liberals and moderates favor marriage equality on the merits, they can now rest assured that a pro-equality ruling would be politically sustainable.

Ethics After Hell: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Embrace Unrealistic Expectations

I think the issue of what happens to ethics if we don't believe in Hell, raised in this week's Time magazine, is an important one for religious and secular people alike. That's because the basic Christian ethical system is an important part of the background culture of the entire west, even for people who don't personally practice a religion or who come from Jewish families or whatnot.

Folk hell has two relevant features. One is that it's really awful. The other is that being sent there is the act of a just and moral God not an arbitrary and capricious one.

One important consequence of this that I think has tended to carry over into secular ethical thought via Immanuel Kant—a serious Pietist Christian who nevertheless devised an ostensibly secular ethical system—is that the rules of morality ought to be realistic and achievable. It can't be that a just and moral God is sending 99.9 percent of the population to a fate of endless suffering in Hell. God is good, so he wants to punish the wicked. But by the same token, God is good so his definition of "wicked" must be something that most of us are able to steer clear of. If we recognize that some people appear to go "above and beyond the call of (ethical) duty" we can recognize their supererogatory goodness by deeming them "saints." But your average, everyday non-saint has to be a realistic candidate for avoiding the fiery pits of hell.

This tends to rule out the kind of ethical principles that say really middle class Americans ought to be giving 65 percent of their incomes over to charity. After all, nobody does that, it goes against human nature to do that, so it can't be that we're all sentenced to hell for being bad people. And I think that a lot of secular people who've dropped the entire God/Hell scheme from their worldview still hold on to a ghost version of that line of thinking. But without hell there's no reason to think of good and bad, right and wrong as a question of getting over some hurdle of minimum standard of conduct.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers