Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2310

May 16, 2011

Slow Progress as the Suns' President Comes Out

By Alyssa Rosenberg

Professional sports are an imperfect meritocracy and a limited driver of equality: participation and success may serve to secure your masculinity in the public eye, the desire to win may prove stronger than racial and sexual animosity, but those are first and fraught steps towards full acceptance and legal protection. All of that said, I'm glad to see Suns' president Rick Welts come out—having openly gay and gay-friendly executives is an important signal to active players in all sports that they will be protected by their organizations if they come out before retirement.

And it's not just that it's useful for gay players to prove that sexual orientation doesn't impact play. Richard Greenberg's play Take Me Out has this wonderful scene about the ways in which sports are a language that for fans, bridge race, class, sometimes gender, and in the world of this drama, sexual orientation. Mason, a gay accountant, goes to his first baseball game and finds:

The crowd was vocal. Because the subject here was baseball, and the stadium was full of scholars—historians—and soon enough, I found myself engaged in learned debate with all these…strangers, these…guys. As for the last several weeks, I'd been conversing with all sorts of people I've never been able to speak to before: cab drivers. My five brothers…And when the winning run crossed home plate, the fans who had stayed rose in this single surge and let out a shout like the "Hallelujah" chorus. And it was the first crowd I had ever agreed with.

He doesn't prove anything to anyone except himself. Given how many times I've thought we were on the verge of having a current athlete, maybe even a star, come out while still in whatever game they're playing, I'm not prepared to say I think it'll happen soon. But I'm happy for Welts, who started his coming out process before Kobe Bryant's outburst, and for the regular reaffirmation of gay people's full participation in every aspect of American life, particularly ones that involve junk food, beer, and wild collective enthusiasm.

Yes, The House GOP Voted To End Medicare

, Politico writes:

DCCC will be out today with a brutal (and misleading) slogan, "VOTE REPUBLICAN – END MEDICARE"

I don't normally like to just repeat things, but I think it's important for all progressives on the Internet to draw a line in the sand under this one. There is nothing even slightly misleading about that slogan. "Medicare" refers to a single-payer universal health insurance program instituted by the Social Security Act of 1965. If a political movement committed to having that program "wither on the vine" and die puts forward a bill to abolish that program and replace it with a system of private vouchers, then it doesn't matter whether or not the voucher program is still called Medicare. That's what House Republicans voted to do, and there's nothing even slightly misleading about calling this an effort to end Medicare. What's misleading is the effort to use nomenclature to obscure the nature of the change.

Journalists respond to feedback from readers. If you see anyone writing stuff like this, send them an email and tell them calmly and politely that you think they're mistake.

Newt Gingrich: Oil Subsidies Are Good Because Liberals Want "All Of Us To Live In Big Cities In High Rises, Taking Mass Transit."

As I've often said, conservative politics in the United States of America has nothing to do with free markets. It has a lot to do with identity politics and it has a lot to do with interest group politics. And speaking on the Martha Zoller radio show recently, thrice-married former House Speaker Newt Gingrich elegantly laid out the nexus between the two by explaining that it would be a mistake to take away oil companies' tax subsidies because efforts to do so are part of a liberal plot to force everyone to "to live in big cities in high rises, taking mass transit."

This whole problem of intellectuals who live on university campuses and take mass transit and then have no idea what the rest of the country is like. I mean, it's nice to have a physicist as the Secretary of Energy, but maybe his experiences of real life on an everyday basis are the same as those of people who live in rural Georgia or people who live in north Georgia. I'm always reminded when people talk about Europe. I did my dissertation on Belgium. Belgium is one-third the size of South Carolina. So when you start talking about traveling in Europe, they're not driving very far and they're not driving cars that are very big. And that happens to be different han America on two grounds—we travel a long way and we like driving bigger vehicles. Now liberals don't like us liking bigger vehicles, so they want to find a way to punish us economically. Hit our pocketbook, make us change, because they'd like all of us to live in big cities in high rises, taking mass transit. That's their idealized utopia.

I'm not sure why Newt Gingrich feels the need to pad his resume here and pretend to have written a dissertation about Belgium. His dissertation was actually about Belgian Congo, a former colony currently known as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is neither small nor located in Europe. Meanwhile, you hardly need to undertake graduate level study to ascertain that Belgium is a small country. By the same token, Rhode Island is a small state. South Carolina is about the size of Austria and considerably smaller than Spain or Italy. This is all irrelevant.

What's not irrelevant is to say that it's true that apartment-dwelling is more common in Europe than in the United States of America. It's also true that transit commuting is done by a larger minorities of Europeans than of Americans. It's also true that European car commuters drive shorter distances on average and drive more fuel efficient cars on average. And it's true that this is in part because the United States does much more to subsidize oil companies. But who is it who's forcing whose lifestyle on whom here? Gingrich wants you to believe that liberals have a dread plot to force everyone into apartments, but he's the one pushing for subsidies and industrial policy oriented around fossil fuel extraction. If some people want to respond to a level playing field by living in apartments or taking a train to work, what's wrong with that? And if it leaves European drivers with shorter car commutes then is that really such a dystopian nightmare?

Making Progressive Movies Gripping: 'Freedom Riders' Tonight on PBS

By Alyssa Rosenberg

When the Sundance Institute's Film Forward festival, which is screening movies in fourteen locations around the world in an effort to spark cross-cultural understanding, swung by Washington last week, I asked a couple of the filmmakers how they overcome one of the most basic problems in political filmmaking: how do you get a message across without getting preachy or boring? Peter Bratt, who made La Mission, said part of the problem was overcoming the idea that independent movies were inherently boring or more studios than they were entertaining: "We get our films from Wal Mart and Target, so to have access to different kinds of movies and to develop a taste for them is important." And Cherien Dabis, who wrote and directed Amreeka, said she'd found the politics of her movie in the personal story. "By the time I was 14, I knew I wanted to do something about media representations of Arabas, but I didn't know how," she said. "I moved to DC after my undergrad to change the world from here…It turns out there was more truth in fiction."

That night, I went to a screening of Stanley Nelson's Freedom Riders, which airs tonight at 9pm on PBS stations everywhere, which is a reminder of a third way. It's easy to make documentaries that rely on cable and C-SPAN clips or stunts. But sometimes you can get a more powerful narrative by reporting the hell out of it:

Freedom Riders starts slowly, but it's very, very good, and Nelson does two things extremely well in it. First, he builds drama out of institutional conflict, drawing out the sense that the Congress of Racial Equality needed a bold move to put it on par with other civil rights organizations, and the extent to which James Farmer and CORE were less prepared than Southern preachers and Fisk University students for the extremity of the violence the riders would face in Alabama. He also is extremely tough on both the Kennedys and Martin Luther King, Jr., something Nelson said was the part of the movie that most impressed Chinese audiences on the Film Forward tour. The audience I was watching the movie with about died at a clip of Robert Kennedy declaring, after asking the Interstate Commerce Commission to enforce bus desegregation, "There are many areas of the United States where there is no prejudice whatsoever."

And second, he draws out the extent to which white Southerners used defense of segregation as a rational to behave like violent, raging children. I'm amazed that Nelson got former Alabama governor James Patterson, whose cravenness nearly allowed a white mob to burn down First Baptist Church with 1,500 black residents of his state inside, to do an interview today. Patterson must have no idea how unreflective he seems when he absolves himself of the violence in Birmingham by saying "Bull Connor never supported me for governor. I never liked the man…He was so unpredictable." He's still the same man who emptied out the dictionary to insist that the Freedom Riders had baited the white people who were beating and bombing them past endurance, saying the purpose of the Rides was "to incense them and enrage them and provoke them into acts of violence."

It's equally incredible to watch Janie Forsyth McKinney talk about what it was like to see the men she knew as a child gang up to firebomb the Greyhound bus that had been attacked in Birmingham, and attacked so it would stop where it did in a trap. "It was like a scene from hell. It was the worst suffering I'd ever heard," she said, explaining the moment she decided to help the Freeom Riders, even at considerable long-term cost. "I took her a glass of water. I washed her face, I held her, I gave her water to drink. And as soon as I thought she was going to be okay, I picked out somebody else." She was twelve, but she was the adult in her family and her community at that moment:

Watch the full episode. See more American Experience.

Department of False Dichotomies

William Wallis profiles Rwandan President Paul Kagame under the headline "Lunch with Paul Kagame: Is the Rwandan leader a visionary statesman, or a blood-stained tyrant?"

Not wanting to comment on the specifics of a region of the world with which I'm not that familiar, I'm left to wonder why this is meant to be an either/or issue. Andrew Jackson is responsible for ethnic cleansing that could make any blood-stained tyrant proud, but he's also the main founder of America's oldest political party, featured on the $20 bill, etc. Napoleon Bonaparte didn't engage in that kind of massacre and displacement, but surely plenty of people died in the wars he launched. Yet he's also an important statesman whose various conquests and administrative reforms shaped the subsequent 200 years of European governance in a profound way. If Deng Xiaoping wasn't a visionary leader then I don't know who was, but that doesn't mean nobody ever got run over by a tank protesting the regime he led.

It's difficult to understand world events by trying to reductively view everything as a struggle of visionary good guys against blood-stained tyrants. Returning to the subject at hand, I think the piece actually makes it perfectly clear that you won't be able to understand Kagame's role through this lens, so it's annoying to see it headlined in this way. Precisely the danger posed by a figure like Kagame is that western leaders will look at his very real and very important accomplishments, conclude that he's "one of the good guys," and then turn a blind eye to real flaws in his conduct. Politicians are normally a mixed bag, and need to be assessed as such.

The Limits Of Mike Huckabee

American politics largely consists of a battle in which the "center" is defined in highly elitist terms, a mix of somewhat right-wing views on economic policy (willingness to contemplate some tax increases as long as they're paired with big spending cuts) paired with slightly left-wing views on social policy (abortion should be generally legal and gays and lesbians should have some rights but let's not push the envelop too quickly please!) leaving the other, more populist quadrant, vacant. Ross Douthat in his requiem for Mike Huckabee says he'll be missed precisely because he occupied that vacant zone:

This combination of views represents one of the plausible middle grounds in American politics. You can find it in the Republican Party, among the evangelicals and Catholics whose votes made the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush possible. You can find it among independent voters, particularly in what a recent Pew report calls the "disaffected" demographic, whose hostility to big government coexists with anxieties about corporate power and support for redistribution of wealth. And you find it in the Democratic Party as well — from the dwindling ranks of pro-life Catholic liberals to the "Bill Cosby conservatives" in the African-American middle class.

I had a rejoinder ready for this, but it came pre-acknowledged later in the column:

Of course, his 2008 campaign also reflected populism's inevitable flaw: a desperate lack of policy substance. Huckabee won votes by talking about issues that the other Republican candidates wouldn't touch, but his actual agenda was a grab bag of gimmicks and crank ideas. And nothing in his subsequent television career has indicated a strong interest in putting policy meat on the bones of his worldview.

But is this really an inevitable flaw of populism? I actually agree that it's an inevitable flaw in the thinking of a lot of people who I see out there calling for populism of one stripe or another. People have decided that the problem is the bankers and that what we need is a populist politician who'll call them out, but don't necessarily actually know what they want to see happen. And it's a mistake to make policy by emotional affiliation rather than dispassionate analysis. But is it actually impossible to combine the populist style with a more rigorous approach to substance? I'd say the John Edwards campaign in 2008 did a decent job. Obviously, his career's wound up being undone by sundry character problems. But the lack of heft to Mike Huckabee's national political persona is, in its way, equally a character problem and a more serious one: He doesn't seem to actually care. He'd rather talk about problems then think of solutions to them. He'd rather host a weekend television show than try to become president.

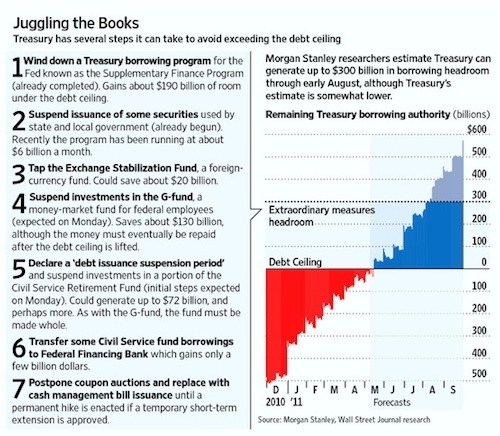

Welcome To The Debt Ceiling

Today turns out to be the long-awaited day that the Treasury Department hits the debt ceiling. To be clear on what this means, it's not that we're "out of money"—the government's been spending more than it takes in ever since George W Bush took office. Nor is it that we're out of borrowing capacity—the global investment community is eager to lend money to the US government at some of the lowest rates on record. Rather, the Treasury Department has run out of legal authority to borrow. This is a big problem. And it's a problem that has an easy solution. Barack Obama, John Boehner, Harry Reid, Mitch McConnell, and Nancy Pelosi all agree that the legal authority should be expanded. But Boehner and McConnell are saying that even though they favor an expansion of legal borrowing authority, they won't agree to one until they get unrelated policy concessions.

So you get what we have here this week. Extraordinary measures to juggle financial obligations. Here's an illustrative graphic from the WSJ of what that looks like:

Note that historically the debt ceiling has just been the subject of substance-free partisan posturing. The idea of using it as a hostage to extract actual policy concessions is brand new and has implications for American governance beyond today.

'Game of Thrones' Open Thread: Whispers and Portents

By Alyssa Rosenberg

As always, please label spoilers for events beyond those portrayed in the aired episodes before in comments. But do feel free to spoil away!

I go to a semi-regular dinner on Sundays where I effectively act as a Game of Thrones interpreter for a group of people who are watching the show mostly cold; they've read at most, the first novel in the series. One of the things that happens all the time is that they'll ask me about the implications of something they've seen on-screen, only for me to tell them that if we tug that thread, we'll unravel thousands of pages of spoilers, storylines that I don't even know the answers to. The way details germinate and bloom into hideous flowers is one of the most impressive and engrossing things about reading A Song of Ice and Fire, and it's one of the things that makes the show an impossibility for casual audiences.

One of the things the show has done best as an adaptation is to draw out personalities that will prove to be important later in the narrative. Almost all of the additions to Martin's narrative have been those kinds of strategic character developments, and they're almost uniformly excellent—last night's episode was a particularly good episode for it, in large ways and in small. Ser Barristan Selmy's remarks about sitting vigil for Ser Hugh, who died at the end of last episode, is just one of the ways the show's played up his role in a way that will have real payoff in subsequent seasons. Similarly, playing up Robert's petty cruelties to Lancel Lannister is useful now and in the future: it illustrates both the smallness of the king's character, and it's an investment in future narratives. And I do love watching Littlefinger and Varys snipe at each other, particularly when they're one-upping each other with rumors about the nobility's sexual habits.

But I think perhaps my favorite addition in this episode is the way it draws out the sexual and romantic relationship between Ser Loras and Renly Baratheon. I'll admit the first time I saw this episode, that surprised me: I've read all the books three or four times, and just missed the relationship Martin implies between them, and was convinced this was an invention out of the whole cloth. I'm not sure how other people will feel about this development, since i know it may read as HBO taking advantage of its license to depict people getting it on (I do wish the actors had kissed. There's still something more taboo about the idea that gay people are tender towards each other than the idea that they have sex.). But I thought the episode did a great job of using the relationship to illustrate other things, whether it's the falseness of the rituals of courtly love and the extent to which Sansa falls for them, or the reach of Littlefinger's knowledge.

I'm not sure, however, how the show's investment in making Cersei Lannister a more sympathetic character is going to pay off. Whether it's the addition of a child she bore Robert who died, or her question to Robert, in a moment of contemplation of their marriage "Was it ever possible for us? Was there ever a time? Ever a moment?" the show has invested heavily in the idea that she's tough but not without some tenderness. I genuinely don't know how that will govern audiences' reactions to events that I assume are still to follow, but for now, I'm trusting David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. So far, they've proved themselves masterful players in their own game.

May 15, 2011

To Hardcore Libertarians, Democratic Government As Such Is a Form Of Slavery

Last week, Rand Paul explained that saying people have a right to health care is a form of slavery. Today on Fox News Sunday, his father Ron Paul suggested that Social Security and Medicare are slavery as well:

Read my colleague Ian Milhiser for a rebuttal of Paul's constitutional arguments. For my part, when I hear this stuff I think of my former professor, the late great libertarian political philosopher Robert Nozick who developed the notion ("demoktesis") that democratic governance is a form of slavery. Nozick is a very smart guy and the position is rigorously argued. That said, regulated welfare state capitalism is clearly not actually the same as slavery. The fact that one can reach the conclusion that it is shows that there's something deeply unsound with the Nozick-style view of property rights and highlights the extent to which libertarian ideology represents a departure from the values of classical liberals in whose work one finds no support for such a conclusion.

Road Subsidies

This pop-up cafe in what's normally a midtown Manhattan parking spot highlights to me the difficulty of really calculating which modes of transportation are subsidized and which aren't:

The point here is that space in midtown Manhattan is extremely valuable. The conventional thing to do with curbside space is to sell it to car owners for parking purposes as sub-market prices, leading to shortages. One policy alternative that's still considered vaguely radical is to sell the space to car owners for parking purposes at market-rate prices, thus ameliorating parking shortages and increasing city revenue. But imagine a city auctioning off a piece of city-owned land and saying "we'll sell it to anyone who wants to put a bike shop here." The severe restriction on permitted uses for the land (to wit: bike shops) would itself constitute a large subsidy to the winning bidder. The normal thing to do would be to auction the land off without restriction so that it can be put to the most economical use.

Given path dependency, the large fixed investments in buildings, etc., it's obviously not very practical for New York City to auction off West 44th Street. But this kind of allocation of expensive space to automative purposes is a major source of subsidy to car owners. Consider not just street parking, but also space-intensive things like the elevated Southeast-Southwest Freeway in DC or the massive patch of "ramp spaghetti" near the Kennedy Center.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers