Scott Berkun's Blog, page 60

February 13, 2012

In defense of Brainstorming: against Lehrer's New Yorker article

Jonah Lehrer's recent article in the New Yorker Groupthink: the brainstorming myth, is a tragedy. It makes many poor conclusions and will do more harm than good.

The article is an attack on the concept of brainstorming, but his assumptions and reasoning are flawed.

I have no stake in brainstorming as a formalized thing. It's a method, and I've studied many idea generation methods. If done properly, in the right conditions, some of the them help. I'm not bothered by valid critiques of any of them. However, sweeping claims based on bad logic and careless thinking need to be addressed.

Here are 4 key things he doesn't mention, which shatter his conclusion:

Nothing matters if the room is filled with morons or strangers (or both). If you fill a room with stupid people who do not know each other, no method can help you. The method you pick is not as important as the quality of people in the room. The most important step in a brainstorming session is picking who will participate (based on intelligence, group chemistry, diversity, etc ). No method can instantly make morons smart, the dull creative, or acquaintances intimate. The people in Nemeth's research study, the one heavily referenced by Lehrer, had never met each other before and were chosen at random. A very different environment than any workplace.

Brainstorming is designed for idea volume, not depth or quality. Osborn's (the inventor of brainstorming) intention was to help groups create a long list of ideas in a short amount of time. The assumption was that later a smaller group would review, critique, debate, later on. He believed most work cultures are repressive, not open to ideas, and the primary thing needed was a safe zone, where the culture could be different. He believed if the session was lead well, a positive and supportive attitude helped make a larger list of ideas. Obsorn believed critique and criticism were critical, but there should be a (limited) period of time where critique is postponed. Other methods may generate more ideas than brainstorming, but that doesn't mean brainstorming fails at its goals.

The person leading an idea generation session matters. Using a technique is only as good as the person leading it. In Nemeth's research study, cited in Lehrer's article, there was no leader. Undergraduates were given a short list of instructions: that was the entirety of their training. Doing a "brainstorm" run by an idiot, or a smart person who has no skill at it, will disappoint. This is not a scientific evaluation of a method. Its like saying "brain surgery is a sham, it doesn't work", based not on using trained surgeons, but instead undergraduates who were placed behind the operating table for the first time.

Generating ideas is a small part of the process. The hard part in creative work isn't idea generation. It's making the hundreds of decisions needed to bring an idea to fruition as a product or thing. Brainstorming is an idea generation technique, and nothing more. No project ends when a brainstorming session ends, it's just beginning. Lehrer assumes better idea generation guarantees better output of breakthrough ideas, but this is far from true. Many organizations have dozens of great ideas, but fail to bring those ideas into active projects, or to bring those active projects successfully into the market.

1. Understanding Idea Divergence vs. Convergence

Lehrer writes:

"While the instruction 'Do not criticze; is often cited as the important instruction in brainstorming, this appears to be a counterproductive strategy. Our findings show that debate and criticism do not inhibit ideas but, rather, stimulate them relative to every other condition."

The intention of brainstorming is not to eliminate critique, but simply to postpone it. Workplaces are notorious for killing ideas quickly with phrases like "We tried that already" or "that won't work here" or even "that's too crazy" (List of familiar idea killers heard regularly in workplaces). Great ideas often seem crazy or weird at first and if they are discarded or criticized before given time to breathe they're lost before they had a chance to show their merit.

In ordinary life when people face big decisions, like where to go on vacation, it's common to come up with a big list of ideas, only adding items for a time. And then once the list seems reasonably long, only then does critique and debate start. This is known as divergence / convergence. You explore and add (diverge) and then cull and refine (converge). Most creative people, and processes, shift back and forth between divergence (seeking, exploring, experimenting) and converging (eliminating choices, simplifying, deciding). Brainstorming and nearly all idea generation techniques are divergence acts. And need to be paired with a separate activity that converges.

Simply put, there is an assumption in most research about creativity that only a singular method is ever used. This is wrong. Most successful creative teams use a combination of methods. Sometimes people work alone, sometimes in groups. Sometimes there is a formal activity, sometimes not. Sometimes the goal is to diverge, sometimes the goal is to converge. Their effectiveness is the combination of all of these activities over the course of a project. But most research assumes there is only one event for creativity that ever happens, and seeks to find the ideal event, which is absurd. I understand the focus on a single activity simplifies research, but it also limits the application of that research.

In Osborn's best book on the brainstorming method, Applied Imagination, he wrote on page 197:

"Although creative imagination is essential… judgement must play an even larger part."

And he details several processes for evaluating, critiquing, and reporting on ideas. On page 200 he states:

"A list of tentative ideas [e.g. the output of a brainstorming session] should be considered solely as a springboard for future action… as a pool of ideas to be screened, evaluated and further developed before solutions can be arrived at."

2. Reading the 2003 Brainstorming Study

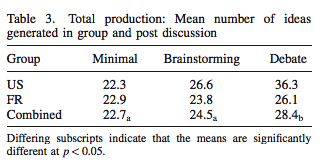

The primary thrust of Lehrer's critique is based on a 2003 study by Nemeth (PDF), where students were divided into groups and given 3 different sets of instructions. In one group, no instruction was given ('Minimal'). In the second group, basic brainstorming rules were given ('Brainstorming'). In the last, brainstorming rules were given, plus students were allowed to critique each others ideas ('Debate'). But no group was trained in how to brainstorm, nor given an example of effective brainstorming to watch.

Is the debate group brainstorming, or not? They were given the same instructions, plus one additional one ('it's ok to criticize'). The results do show that the group that could critique generated more ideas: but not many more. For all the participants, it was a difference of ~4 ideas. 28.4 ideas for the "debate" group and 24.5 for the "brainstorming" group. About 14%. In the U.S. this number was much higher, closer to 30%.

But these columns are mislabeled. The debate groups was given brainstorming instructions, as well as an instruction to debate. It should be labeled "Brainstorming with debate". If the only instruction they were given was to debate, it'd be a fair comparison. But it isn't.

3. Is Brainstorming Useless?

Lehrer's writes:

"But if brainstorming is useless, the question still remains: What's the best template for group creativity?"

He's wrong. The data from Nemeth claims brainstorming (Column 2 in the table above) is more effective than giving people no advice at all, but not as effective as brainstorming where criticizing is allowed. I don't agree with Nemeth's conclusions, but Lehrer does, and assuming he'd read the study he'd have seen the table above which show brainstorming generated more ideas than the control group.

More importantly, he's asking the wrong question. There is no singular best template for group creativity. When I'm hired to advise teams, the first thing I do is study the culture of the team. My advice will be based on who they are and what will work for them, not on an abstract set of principles. Just as there isn't a best template for group morale, or teamwork, or group anything. Is there a singular best template for good writing? For being a good person? A singular template denies how divergent individuals, teams and cultures are. Nemeth's data shows a wide disparity between French and American success at brainstorming: clearly culture does matter.

Lehrer assumes there is a universal principle that, if discovered, would make everyone more creative. This works against the very idea of creativity: which is that each person sees the world in a different way, and it's through exploring those differences, rather than avoiding them, than new and different ideas can be found. For groups, this means each group has it's own strengths and weaknesses, and what will help or hurt their creative output will differ. Some teams are too freewheeling, others not enough.

4. Anecdotes, Data and MIT's mythical building 20

Lehrer goes on to discuss The legendary building 20 at MIT's Cambridge campus. He writes:

"Building 20 and brainstorming came into being at almost exactly the same time. In the sixty years since then, if the studies are right, brainstorming has achieved nothing – or, at least, less than would have been achieved by six decades worth of brainstormers working quietly on their own. Building 20 though, ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time, a space with an almost uncanny ability to extract the best from people. Among M.I.T. people, it was referred to as the magical incubator."

MIT is one of the greatest concentrations of brilliant people in the history of the world. The campus is filled with buildings where great things were invented. Lehrer offers no data about the number of inventions discovered in Building 20 vs. Building 19 or E15 (where the famed Media Lab resides). He mentions Building 20 "ranks as one of the most creative environments of all time", but there is no actual ranking. If you wanted to measure the magic of building 20 scientifically, you'd perhaps replicate the building in the middle of an empty field in Kansas, and fill it with average people. Does magic happen? More magic than other kinds of buildings in the same place? Nehmer's brainstorming studies were done with random college undergraduates who had just met. If you want to compare brainstorming to Building 20, you'd need to try to place some fair comparisons, which Lehrer does not do.

I agree environment matters, but there's plenty of evidence great things happen independent of environment. There was nothing magical about the buildings used for the Manhattan project. Nor for the NASA engineers who worked on the Apollo 11 moon landing mission. The car garage is the prototypical silicon valley environment for innovation, and many ideas that drive our tech-sector came from garages and cubicles. How does the legend of Building 20 compare with these other buildings? What shared lessons can be learned that incorporates these diverse examples of environment? Lehrer doesn't say. In building 20, what idea generation techniques did they use (and was brainstorming one of them?), or did they all just meet randomly in corridors? He also doesn't say. Did they work together at blackboards? At the cafe? I'm sure they used many different methods, and the combination of those methods matters.

5. The only lessons I can derive

The best lesson I can pull from Lehrer's mess of an article is this: creativity is personal. Building 20 was built cheaply and seen as a failure, which made it easier for motivated creatives to rearrange and redesign the environment. There were fewer rules than your typical building. They were allowed to take control over how they worked. The diversity of people forced people to hear different points of view. And the highly empowered and competitive pool of makers ensured things would ship, and not languish in bureaucracy or self-doubt.

If you want more creativity, hire people who demonstrate creativity. Do not expect to magically graft it onto people you hired for their rigid conservatism. Then give them resources and get out of their way. Let them decide what methods to use or not. If you want to know how to generate ideas in groups, go find a creative group and watch what they do. You'll learn more from observing that experience than Lehrer's article.

Related: A previous defense of Brainstorming against Marc Andresen, with supporting links.

Related posts:

In defense of brainstorming

Microsoft no more

#34 – How to run a brainstorming meeting

Do headlines make us dumber?

Last stop: Adobe

February 11, 2012

Edison vs. Tesla: two approaches to problem solving

Two heroes in the pantheon of inventors are Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. Of their many contrasts, a favorite was their divergent approaches for how to solve problems.

Edison is famous for his affirmations of hard work as the key ingredient in invention:

"Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration"

"I have not failed 700 times. I have not failed once. I have succeeded in proving that those 700 ways will not work. When I have eliminated the ways that will not work, I will find the way that will work"

It's good advice. The idea for something is rarely the hardest part. Instead, it's the willingness to work on the long list of little issues that must be solved to bring an idea to fruition (or the marketplace). In problem solving lingo, this kind of approach is called brute-force. You apply great energy to exhaustively try out every different alternative.

Tesla had a different approach. His intuitive understanding of the principles of science allowed him to think about problems in ways Edison either could not, or did not want to. Tesla wrote:

"If Edison had a needle to find in a haystack, he would proceed at once… to examine straw after straw until he found the object of his search. I was a sorry witness of such doings, knowing that a little theory and calculation would have saved him ninety per cent of his labor."

Both of them were right.

The best approach to problem solving is synthetic: to use the synthesis of both ways of thinking to serve you. You should be willing to apply brute-force, but also be willing to do thinking in advance to make solving a problem easier.

Decades ago, in my computer science classes, I recall a clear division among my programmer peers. When given a new assignment, some would jump right in to writing code. I'd call them little Edisons. Others would put the keyboard away, and think for a while on paper. They'd sketch things out, and perhaps ask a question or two online. These were the little Teslas.

Which are you?

Related posts:

Why Jobs is No Edison

Problem Solving & Kobayashi Maru

This week in ux-clinic: Designing for novices and experts

Innovation vs. mere improvement: how do you know what you have?

The early days of dogfood

February 10, 2012

Livestream 9am PST: Creative thinking hacks

I'm speaking today at Creative Mornings Seattle on Creative Thinking Hacks.

I just learned there will be a livestream. You can tune in at 9am PST to watch/listen.

Description: Scott will simultaneously demystify creative thinking, provide tips and tricks for finding ideas, provoke wild opinions and comical rants, and explore how to become more powerful at the creative aspects of your work and life. 20 minutes + 20 minutes Q&A.

Livestream here (at 9am): http://www.ustream.tv/channel/seattle-creative-mornings

No related posts.

February 7, 2012

The 5 best books on Innovation EVER

Before I share the list of the 5 best books on innovation, here's a list of 5 things you need to know before reading that list. It's worth it. I promise.

There are 100s of books on innovation. Most are terrifyingly (and ironically) boring. They're bought to be placed, unread, on office shelves so people can pretend they're smart. These books are cliché in the worst way, cherry picking trendy examples and building worlds of junk theories around them, theories the heroes in the cherry picked examples didn't even use. Innovation is a junk word, and there are many junk books.

It's not clear why anyone should read a book about innovation. There's little evidence people we'd call creative got that way by reading a particular book. Most skills in life are only acquired by work, and to be more creative means to create and learn, rather than merely read.

I carefully studied over 60 books, related to creativity, invention and managing creativity in others during research for my bestseller, The Myths of Innovation (research that included teaching a course on creativity at the University of Washington – syllabus). And I've read more books before and after than project. I even organized the books I studied in an innovative way for readers. I've been studying creativity in many forms for a long time and my list reflects wide and deep reading.

People looking for a book on innovation often make the mistake of compressing the many sloppy uses of the word into a single thing, and expect one book to excel at teaching people how to: 1) Generate ideas and invent things 2) Design and ship good products 3) Run a successful entrepreneurial business. These are very different skills, possibly even different subjects.

These 3 skills are rare. It's insanely rare for one person to have two, much less three of them. It's improbable any book could single-handedly give you one of these skills, much less all three. Any book claiming to do any of this is lying to you.

There. All done.

I can confidently say if you only read 5 books these are the ones to read and re-read:

Innovation and Entrepreneurship, by Peter Drucker. Drucker is profound, clear, concise and memorable. He puts modern business writers to shame with his clarity. This short books encapsulates all of the theory you need to think about starting a business, and what it will take to find, develop, launch and grow product ideas. (Also see, The Art of the Start, Guy Kawasaki, and if you work in the tech-sector, Founders at Work is a must-read)

Thinkertoys, Michael Michalko. There are many books with exhaustive lists of methods for generating ideas. This is one of them. The misconception is that idea generation is the hard part, which it rarely is. But for those looking for games, tactics and methods to generate ideas this is a great place to start. (Also see, Are your Lights on?, by Gause and Weinberg).

Dear Theo, By Vincent Van Gogh (& Irving Stone). Before you dismiss this one, consider this: what we call passion in the business world, is passion for profit. What if there was no profit motive? How much passion would our heroes, like Edison and Jobs, have had for the ideas alone? To learn about the deepest commitment to ideas you have to study artists. There are no better stories of passion than great artists pursuing their creative visions against all odds and Van Gogh's letters are a fantastic encapsulation of commitment, vision, dedication, brilliance, work ethic and madness, all traits any creator or entrepreneur should understand. (Also see, The Agony and the Ecstasy, for a similar book about Michelangelo).

They all laughed, Ira Flatow. History is biased in that we retroactively inject purpose and narrative structure into stories of invention, so that they make more sense to us in the present. But the real history of invention and discovery is messy, weird, frustrating and surprising. This book documents how frustrating it usually is to have a great idea in a mediocre world. (Also see, Connections, by James Burke – all episodes of the documentary based on the book are free online).

Brain Rules, John Medina. I've read many books about intelligence and neuroscience – they're mostly pseudo-fluff, filled with the latest theories and shocking claims, but lead to no tangible improvement in how you use what's between your ears. Brain Rules is the book to read about how to use your brain to better use your brain. While it's not strictly about creativity, show me a creative person who didn't use their brain well (See my full review of Brain Rules here).

There. Have fun.

Most of these books are old. Well guess what? Innovation and creativity are old too. The best advice is not necessarily the newest, despite our compulsive neophilia. Just be glad I didn't recommend Vitruvius' ten books on architecture (which happens to be one of the only sources for the story of Archimedes and 'Eureka').

But I implore you to do more than read. Like learning to play guitar, you can only learn so much from books. You must get to work yourself. It doesn't matter what you make, but go make something. And when you finish, think about how to make it better and try again. This is the only thing that will make you more creative: the practice of making things. And only then can what you learn from books matter.

Related posts:

The best creative thinking books

The explosion of innovation books

Slashdot review of Myths of Innovation

The other myths of innovation?

Innovation in a book about Innovation?

January 31, 2012

The top mistakes UX designers make: the writeup

Last week I spoke at the Puget Sound SIGCHI meeting. Since it's a group of designers and user researchers, I let them participate in picking the topic, and top mistakes won by a wide-margin.

Rather than talk about tactical mistakes, such as in prototyping and running studies, I focused on the ones we overlook the most, about attitude and culture.

Here's the list I used during the talk:

The top mistakes

Not credible in the culture. Most designers and researchers are specialists, making them minorities in the places they work. Most training UX people get assumes they are working alone, which is rarely true. This means their values and attitudes likely don't match the work culture of most companies. The burden to fit in, or to recognize what the culture value's and provide it, is on the specialist. If you are the best designer alive, but work in a place ignorant of design, your lack of credibility in the culture renders your design ability useless. Being a specialist means you will always be explaining what you do, your entire career, including translating your value into a language your coworkers can understand.

Never make it easy. The first users you have are your co-workers. How easy is it to follow your advice? As a specialist, its easy to become the UX police, scolding and scowling your way through meetings. No one likes the police. Generally, people do what is easiest to do. If your work creates more work for them, they will naturally want to avoid you. Specialists often scowl from ivory towers, where they provide advice that is hard to follow, or sometimes, hard to understand as it's not in the language of the culture.

Forget your coworkers are meta-users. Unless you write production code, you are not actually building the product customers use. You make things, specs, mockups, or reports, that are given to others who must convert your work into the actual product. This means you must design both for you actual customers, and for your coworkers, who are the first consumers of your ideas. Usability reports are often tragically hard to use. Mockups and design specs often forget details developers need such as sizes in pixels, and hex colors.

Never get dirty. In many tech cultures there is plenty of dirty work to do: mainly finding bugs and reporting bugs. Anyone can do it, but no one wants to do it, and everyone avoids it. Often there are bug bashes or engineering team events to find and deal with bugs. As a specialist, its easy to go home early while the development team stays late to do the dirty work. If you're part of the culture, you'd stay and help when there is dirty work to be done. But if you're a consultant, you'd go home. How do you want to be perceived? For people who don't know what you do, helping out with the dirty work may be the first way to earn a positive reputation, or to make that first friend or two.

Pretending you have power. Most specialists play advisory roles. They give advice. There is nothing wrong with being an advice giver. The challenge in being an advice giver means the critical skill for success is persuasion and sales. You need to be an expert at selling your ideas. To pretend that you don't need to sell your ideas, is to pretend you have power. Advice givers should be evaluated heavily on how much of their advice is followed. Giving advice is easy. Getting people to follow it is where your value is.

Ignore possible allies. Among your co-workers, one of them loves you the most (or hates you the least). If you are not enlisting them to support your requests, or give you feedback you're ignoring your possible allies.

Vulcan pretension. There are deeply embedded value systems among designers and researchers that are self destructive. For research, its Vulcan: "I research, analyze, and produce data. I do not offer my own opinion ever." But everyone else does give opinions, and in many cases the opinion of a researcher is more valuable. Researchers should say feel comfortable saying "This is not based on data, but I think…" which protects the integrity of data, but allows them to offer opinions just as everyone else does.

Dionysian pretension. For designers, its the dreamer mentality as an excuse for not having to do the thinking required to make an idea real. "I just come up with ideas for things, its not my job to figure out how to make it work." This is related to never getting your hands dirty, as all ideas have dirty work required to make them real that must be done, and if the person coming up with an idea does not participate in the process, it demotivates everyone else from wanting to follow that idea.

Don't know the business. Everyone should know why they have a job. Who decided to hire a UX person instead of another developer? What argument did they make? Find out. Find out how the company makes money and which kinds of decisions are likely to make profits grow. Having a better UX doesn't guarantee anything: many market leading products are UX disasters. How can this be? If you don't know how that's possible, then you don't understand how many other factors beyond UX are involved in your business.

The advice

Earn credibility in your culture on your culture's terms.

Make it easy / fun to follow your advice.

Design for your developers/managers, as they are the first users of your work.

Have something at stake

Consider switching to a role with power

Seek powerful allies

Get out of your office and drop your ego

Follow the money

Notes from the Q&A at the talk

Thanks to Emily Cunningham (@emahlee), here are some notes from the Q&A during the talk:

How do you become credible? (Audience question)

Ask your best ally (who is not in your job role) that question.

Don't always change the conversation in meetings to ask the same question you always ask. You've become a UX robot, always saying one of the same 3 things.

Saying the same things over again and again, but not affecting change isn't helping anyone.

Know and be aware of "what conversation are we having?" for each meeting (tip from audience)

Good Project Managers empower the people in their team. But good project managers are rare.

How do we educate our co-workers of our value?

Most people have no idea what you do.

Part of your job is always being able to give the 101 talk well.

You can't do it en masse so divide and conquer:

Ask your co-worker, "I'd like to talk to you about what I do so I can get your feedback on what I'm doing." The next meeting you'll have one more person (hopefully) on board and who understands what you do.

People want data (observation from audience member)

Data gives you credibility.

Video clips give you credibility.

Anyone can go capture video of the product being used.

Pay attention to how decisions get made:

What data works? Is it numbers? Stories? Who yells the loudest?

Are you sure decisions are made in meetings, and not in private discussions?

Does the VP always make the decisions? Who do you know who has the ear of the decision maker?

Seek informal channels – Conversation at people's desks, or over coffee.

Another Mistake: Never Make It Easy

Designers have multiple users along the way, for instance, developers who get our wireframes, with color codes, pixel sizes, or CSS they can reuse, are happy developers.

Developers are always busy juggling 9 things they need to get done.

Set it up so the devs get some reward every time they work on your design. What positive reinforncement of the behaviors you want do you provide?

Film analogy and design decisions

Film has hundreds of people working on it. But there are only a few people who have enormous power. Out of 500 people, maybe six or seven people have power over the creative direction of the film.

Amazon and Microsoft's designs are an "averaging out" of many people's input. (This goes back to the earlier point that design expertise is weighted less than dev expertise).

When there are smart, confident people working on things they are passionate about, there's going to be unavoidable messiness. There is no ideal team where everything goes smoothly and every decision is contention free.

Inspire people to do things they wouldn't otherwise do. Have vision (observation brought up by audience member)

There's a thin line between being inspiring and being a douchebag. One person's inspiration is another person's annoyance. The most inspiring thing a person can do is to work hard on problems they care about that align with what the team cares about, share that work with others, gracefully take feedback, and continually produce.

Related Posts:

What they didn't teach me about UX in college

Why Designers Fail

What do you think we missed? Leave a comment.

Related posts:

Mistakes Critics Make (and Solutions)

This week in ux-clinic: managing sensitive designers

Program Managers vs. Interaction designers

Why do designers fail? Interview w/Adaptive Path

5 Dangerous Ideas for Designers

January 25, 2012

Is speaking easier than writing? Some advice

I get many emails asking about writing, in response to the popular posts I've written about writing. Recently Shawnee M. Deck wrote in asking about writing ones life story.

I was immediately appalled by my lack of ability to put down on paper the words that seem to make everyone laugh whenever I tell my stories.

This is common. Spoken language and written language work differently. The skills needed to tell a good story in one do not necessarily transfer to the other. Our ears are more forgiving than our eyes. When listening, we can use people's tone, pace and volume to get more information about what they are saying. When reading, we get none of that information. The words have to stand alone. It takes more skill to keep people's attention in writing than in speaking.

Some writers do voice to text transcriptions, talking into a microphone and having software convert it to text. Give it a try. If that works for you as a way to get a draft down, go with it. But know that it will need heavy revising to appear like good writing to a reader.

Should I leave a lot of the grammar errors to my editor? What should I expect from my editor in general?

The more you know the better, but yes, any copyeditor should be your grammar expert. Editors come in two flavors: copyeditors and development editors. The former will correct your grammar and give you feedback on sentences, paragraphs and low level writing. The later, which is harder to find, is someone who can give you guidance on the overall direction, approach and voice of the book. Sometimes you can find one person who does both. Publishers sometimes have a third kind called acquisitions editors who find and negotiate with authors to sign book deals, but are often less involved in the process afterwards.

What format would you most suggest? Organized by subjects categorically? Organized chronologically? For now, I'm just getting the chapters down based on my outline.

There's no right answer. A good book can use any of these methods, provided the writer uses the one they choose well. For now, I'd agree – it doesn't matter. Just get your stories down. When you have a complete first draft, you can come back and change your mind about how it's organized. If you plan for a second and third draft, which you should, you can happily postpone sorting out questions of form or structure. An outline helps get the first draft down, but there's no law requiring your second draft uses the same outline.

Should I buy a lot of books (other than yours) and spend a lot of time researching how to write "memoirs" or should I spend a lot more time just writing.

The answer is both. You need to write and get feedback, and read and take notes (What worked in a book? What didn't? Why?). You can also read many more hours a day than you can write (even pro writers don't spent more than a handful of hours a day creating new work). If you read books related to what you are writing about, or in the same style, it will inform you of what you want to aim for, as well as avoid. As far as memoirs, check out Joan Didion, Ted Conover, Annie Dillard, Loren Eisley or any book in the Best American Essays series (there's one for each year for at least the last decade). Most of the essays are memoirs or non-fiction, giving you a sampler pack of writers you might want to study.

Related posts:

Chapter 4: London

Draft 2 – Chapter 4

The waiting

Drafts of drafts

From the mailbag: Best request ever for writing advice

January 23, 2012

On insecurity and writing

A good friend mentioned he'd write more often if he dealt with his insecurities about writing.

I look at this differently.

All writers are insecure: they have doubts and fears that never go away. Kafka didn't want any of his books published, and lived with perennial doubts about his talents. Fitzgerald and Hemingway both despaired about the quality of their current projects, whatever they were, afraid their new works wouldn't measure up to their last (despite feeling this way about their previous works too). Talk to any creator while they are creating and insecurity is everywhere. Will this work? Is this the right choice? Should I cut this or make it bigger? It's part of the deal, as making something means you have to find your way as you go.

Anyone who creates anything has an endless game of ping pong between confidence and fear going on in their minds. And although one might score an ace or a slam, neither ever wins, it's an endless game. Complete confidence creates shitty work, and complete insecurity ends work altogether. Both confidence and fear are needed and must be lived with, not eliminated. Experience with creativity means familiarity with this process, not an avoidance of it. Fear can be an asset if you use it as fuel for your fire, instead of as means for smothering it, or never starting it to begin with.

Writing is hard. Painting is hard. Competing at sports is hard. Everything interesting is hard. The risk of failure is what makes the challenge interesting. Take away any chance for failure, which you'd need in order to feel completely secure, and you take away motivation.

I say choose to do it anyway. So what if it's bad? So what if no one likes it? So what if you read it and don't like it yourself? So what so what so what so what. SO WHAT. At least you will have done it and can decide not to do it again. But to spend hour after hour just thinking and talking and torturing yourself about something you don't do, while pretending, based on zero study of the craft, that there is a magic way to avoid all the hard parts no other productive maker has ever avoided, is beyond arrogant – it's insane.

It's okay to be insecure. Just be insecure about something you are actively making, instead of being insecure about some imagined reality that will never exist if you don't sit down, shut up and get to work.

Related posts:

Need a new writing tool: help?

From the mailbag: Best request ever for writing advice

Writing plan

Daily writing plan

How to start writing a book (mailbag)

January 18, 2012

Quote of the day

The quote of the day:

"All power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The more I've learned, the less I believe it. Power doesn't always corrupt. What power always does is reveal. When a guy gets into a position where he doesn't have to worry anymore, then you see what he wanted to do all along."

-Robert Caro, Interviewed in Esquire, 12/16/09

Related posts:

Quote of the month

Why ease of use doesn't happen

What do you miss from the past?

Your quota of worry and how to shrink it

Quote of the month

January 11, 2012

What should I talk about? (Puget Sound SIG-CHI)

I'm speaking this month at the Puget Sound SIG-CHI meeting (1/26, 6:30pm, location TBD) , a cool group of designers, researchers and UX-minded folks.

Since it'd be daft to pick a topic without some form of user-research, I'm asking you, here and now, what you'd most like to have me talk about. Here are some suggestions:

The top 10 mistakes UX people make

Why designers fail

How to be persuasive

What I wish I'd learned in college (about UX)

Why the world is hard to use (and always will be)

What I learned designing WordPress.com

If anything in the list resonates, leave a comment. Or offer a suggestion please. Thanks.

No related posts.

January 3, 2012

Self-publishing vs. working with O'Reilly Media

I met Joe Wikert, GM at O'Reilly Media, in 2008, while negotiating terms for Confessions of a Public Speaker. I've talked to many editors and executives at publishing companies, but he quickly charmed me with his genuine intelligence and honest good nature. Like my editor at O'Reilly, Mary Tressler, he's one of my favorite people at O'Reilly Media.

When I decided to self-publish my newest book, Mindfire: Big Ideas for Curious Minds, many people assumed there was some bad blood between O'Reilly Media and myself. It was one of the most common questions I heard, despite it not being the case.

When Joe asked to interview me about self-publishing, I imediately said Yes, as this is exactly the kind of good natured curiosity, and interest in providing a level playing field, that made me happy to work with Joe and O'Reilly Media in the first place.

We talked about the choices I've made, what I learned, advice I have for authors and publishers, and more (here's Wikerts summary).

Related posts:

The age of the platform: lessons on self-publishing from 4 time author

Free chapters from Confessions

Calling bullshit on social media

How to call BS on a social media guru (event)

Why I'm self publishing my next book