Scott Berkun's Blog, page 58

April 11, 2012

How to discuss politics with friends, v2

My good friends Royal Winchester, Rob Lefferts and I like to discuss big things. We realized we avoided topics, mostly political, for being too polarizing. But we discussed this, and came up with one set of rules for discussing politics with friends (v1).

Over time we revised it and improved it. Here's version 2:

What is the actual question being discussed? We often stumble into political discussions, seeded by one fact or recent news. As the discussion gets rolling, there are different perspectives on what the actual question being discussed is. Taking a moment to restate the question, or issue, clarifies for everyone exactly what the discussion is about. It sounds silly, but asking "what are we arguing about?" forces everyone to more clearly state their position, or what they think is the core point of disagreement, which can only elevate the quality of discourse.

What do you actually know? We hear factoids third hand and draw large conclusions supporting our pet theories. We rarely read the studies mentioned in the news, or examine the sources of articles we read online as the concept of confirmation bias, where we cherry pick facts we like and call it research, is a human failing. This means we rarely have the depth of understanding to match our emotions. Poking at our sources and recognizing how many assumptions are being made, or both sides, disarms conversations. It's easy to misconstrue facts or manipulate data and having volumes of it means nothing, as both sides have ample ammunition.

Can you effectively argue the opposing point-of-view? We forget that an argument is just a tool. In any complex issue, there are valid points on all sides. If you can't effectively argue the other side's point of view, you can't claim to have seriously considered your own position, as you've never truly evaluated any alternative (or haven't done it in years). Switching sides in a debate is a fantastic exercise: it forces you to use more intelligence and critical thinking than defending the same view year after year ever could.

What would convince you that you are wrong? If you can't imagine any possible way to have a different opinion, then you are not willing to think, and you probably shouldn't be talking about whatever it is. Not being willing to think makes you boring to talk with. If you can't imagine the world being any other way, then you are stuck in your own belief and likely confuse stroking your old well worn thoughts above having to think up new ones.

Why do you believe what you believe? We assume we have great reasons for our opinions. This sometimes is not true. Maybe you believe what you believe because your parents did? That's not a logical basis for believing anything, as it doesn't involve any of your own thinking. It's ok to believe in it anyway, but understanding why you believe will change the way you talk/defend/promote those beliefs.

Why are you interested in having a discussion about it? Is the goal to explore ideas and learn, or to compete?

What are you going to do about it? Assuming you're right, and passionate about your views, why do you think discussing it with a friend will change anything? There are many ways to support political causes and campaigns, and investing your energy there will likely be more satisfying and have more of an impact. If you're not willing to put your own energy behind something you claim to believe in, why should anyone else take your ideas seriously? We pretend so much is at stake in our position, but most of the time we don't care enough to take action. Yelling at a friend is a very unproductive way to support your own beliefs.

Related posts:

How to discuss politics with friends, version 1

April 10, 2012

What to do when things go wrong

This is an excerpt from Making Things Happen, my bestseller on leading project teams.

This is an excerpt from Making Things Happen, my bestseller on leading project teams.

1. Calm down. Nothing makes a situation worse than basing your actions on fear, anger, or frustration. If something bad happens to you, you will have these emotions whether you're aware of them or not. They will also influence your thinking and behavior whether you're aware of it or not. (Rule of thumb: the less aware you are of your feelings, the more vulnerable you are to them influencing you.) Don't flinch or overreact—be patient, keep breathing, and pay attention.

2. Evaluate the problem in relation to the project. Just because someone else thinks the sky has fallen doesn't mean that it has. Is this really a problem at all? Whose problem is it? How much of the project (or its goals) is at risk or may need to change because of this situation: 5%? 20%? 90%? Put things in perspective. Will anyone die because of this mistake (you're not a brain surgeon, are you?)? Will any cities be leveled? Plagues delivered on the innocent? Help everyone frame the problem to the right emotional and intellectual scale. Ask tons of questions and get people thinking rather than reacting. Work to eliminate assumptions. Make sure you have a tangible understanding of the problem and its true impact. Then, prioritize: emergency (now!), big concern (today), minor concern (this or next week), bogus (never). Know how long your fuse is to respond and prioritize this new issue against all existing work. If it's a bogus issue, make sure whoever cried wolf learns some new questions to ask before raising the red flag again.

3. Calm down again. Now that you know something about the problem, you might really get upset ("How could those idiots let happen!?"). Find a way to express emotions safely: scream at the sky, workout at the gym, or talk to a friend. But do express them. Know what works for you, and use it. Then return to the problem. Not only do you need to be calm to make good decisions, but you need your team to be calm. Pay attention to who is upset and help them calm down. Humor, candor, food, and drink are good places to start. Being calm and collected yourself goes a long way toward calming others. And taking responsibility for the situation (see the later section "Take responsibility"), regardless of whose fault it was, accelerates a team's recovery from a problem.

4. Get the right people in the room Any major problem won't impact you alone. Identify who else is most responsible, knowledgeable, and useful and get them in together straight away. Pull them out of other meetings and tasks: if it's urgent, act with urgency, and interrupt anything that stands in your way. Sit them down, close the door, and run through what you learned in step 2. Keep this group small; the more complex the issue, the smaller the group should be. Also, consider that (often) you might not be part of this group: get the people in the room, communicate the problem, and then delegate. Offer your support, but get out of their way (seriously—leave the room if you're not needed). Clearly identify who is in charge for driving this issue to resolution, whether it's you or someone else.

5. Explore alternatives. After answering any questions and clarifying the situation, figure out what your options are. Sometimes this might take some research: delegate it out. Make sure it's flagged as urgent if necessary; don't ever assume people understand how urgent something is. Be as specific as possible in your expectation for when answers are needed.

6. Make the simplest plan. Weigh the options, pick the best choice, and make a simple plan. The best available choice is the best available choice, no matter how much it sucks (a crisis is not the time for idealism). The more urgent the issue, the simpler your plan. The bigger the hole you're in, the more direct your path out of it should be. Break the plan into simple steps to make sure no one gets confused. Identify two lists of people: those whose approval you need for the plan, and those who need to be informed of the plan before it is executed. Go to the first group, present the plan, consider their feedback, and get their support. Then communicate that information to the second group.

7. Execute. Make it happen. Ensure whoever is doing the work was involved in the process and has an intimate understanding of why he's doing it. There is no room for assumption or ambiguity. Have specific checkpoints (hourly, daily, weekly) to make sure the plan has the desired effect and to force you and others in power to consider any additional effort that needs to be spent on this issue. If new problems do arise, start over at step 1.

8. Debrief. After the fire is out, get the right people in the room and generate a list of lessons learned. (This group may be different from the right people in step 4 because you want to include people impacted by, but not involved in, the decision process.) Ask the question: "What can we do next time to avoid this?" The bigger the issue, the more answers you'll have to this question. Prioritize the list. Consider who should be responsible for making sure each of the first few items happens. Also ask: "How can we minimize the odds avoiding a repeat of this last crisis won't create a new crisis in the future?"

—————-

If you liked this, you should check out Making Things Happen - a book filled with 400 pages of distilled wisdom like you just read.

Related posts:

This week in pm-clinic: Plan for the plan

Making things happen – the cover & more

Berkun plan 2004

Things not to say – "We don't have time"

Stupid things presenters do (and how to stop them)

April 9, 2012

Jiro Dreams of Sushi: movie review

This film Jiro dreams of Sushi models itself on its subject, a legendary sushi chef at Tokyo's Sukiyabashi Jiro. Both the movie, and Jiro, are methodical, patient, simple, enigmatic and inspiring.

I enjoyed the film primarily as a meditation on work and living a life dedicate to perfecting a skill. Jiro is 85 years old, and has been making sushi for decades. He came to become a chef on his own terms, without support from his family. The film centers on his sushi restaurants, and how they prepare and serve food.

There are tangents into his life and the lives of his two sons (also sushi chefs), which reveal much about their collective approaches to life. It's a simple film, just as the methods Jiro employs are simple. But in both cases that simplicity allows for great care to be put into every little decision. Sukiyabashi Jiro is one of the few restaurants in the world with a Michelin 3 star rating.

The film helped me ask myself several important questions:

How do you know you have the right priorities?

Why does craft matter? How much of your life should you put into your craft?

What does work / life balance mean? Is that even the right dichotomy?

Is excellence more important than pleasure?

Are each these people happy? Are they fulfilled? Why? Why not? How can I know?

Where do I see craft of this level of skill around me in my world?

If you like any of these questions, and like sushi or craft, you'll find the film of interest. It's a meditative and beautiful film, with many moments without dialog as you watch work being done, providing plenty of space to fill with your own thoughts, and perhaps, your own dreams.

It's an independent film, and you can find where it's playing near you here.

Related posts:

The Tree of Life: Movie Review

Into the Wild: movie review (& more)

Movie Review: Winters Bone

The Social Network: movie review

What every movie review website needs

Ideas vs. Time: how long does an idea take to develop?

People often ask writers and filmmakers how long they worked on their most recent project.

The mistake made is people think in terms of calendar time, instead of time spent actually working on the project. A month can go by where zero hours of work on the project happen. But on the other end of the spectrum, a week can go by where 80 or 90 hours are spent working on the project. Calendar time vs. Working time are often two different values.

This means if someone says "It took me a year to write the book" that could mean a wide range of actual time invested.

For most of my books so far, it took a year of full time effort. About 6 months to write a first draft, 6 weeks to write a second, and the rest for revisions, copyediting and promotion.

50 weeks x 40 hours = 2000 hours.

It's worthwhile for people with 1000 great ideas to think about that number. You find similar numbers for making movies, startup companies, albums, games, novels, or anything of note.

How many hours are you willing to put into delivering on your idea?

The greatness of an idea is irrelevant if you don't put in the hours needed to see it to fruition.

Related posts:

This week: when the party's over

Need a new writing tool: help?

How to write songs and the creative process

Daily writing plan Part 2

PM Clinic, Week 1: Prioritizing time

Mindfire: Typos wanted

I'm working on a 2nd edition of Mindfire: Big Ideas for Curious Minds, to clean up some typos and to make other minor fixes. If you found a typo, I'd be grateful if you'd list it here.

This is the current list of known corrections:

page 30: while at the same time pleasing others.. / pleasing others.

page 60: Less spacing above Bonus

page 104: Four kinds of mistakes should be on pg 105

page 123: unique wonder in this universe that is you . (period is on next line)

page 137: in place of actual thinking.. / thinking.

page 162: "Greatest American Essays" / Best American Essays

page 168: 8. Does transparency matter? / should be top of pg 169

page 174: Page break: misappropriate the word.

Related posts:

Usability review #4: Simplygoogle

Being Popular vs. Being Good

Last chance to pre-order Mindfire (my 4th book)

Wednesday linkfest

Need ideas: fun rewards for Mindfire book pre-orders?

March 29, 2012

Software is not epic

"The whole world is pretending the breakthrough is in technology. The bottleneck is really in art."

- Penn Jillette

I love making tools for people. And software is one kind of tool in the universe.

But I don't think software, or any tool, is an epic creation. A tool is something you make so someone else can make something. We know Martin Scorsese's name, but not the names of the people who made the tools he used. Why? Movies are epic. They are a first order creation, the end product of a creative mind. Software, except perhaps for games, are a second order creation: they are used by other people to make first order creations. Making great software demands creativity and hard work, but its purpose is to allow others to do work, not to be appreciated as a thing on its own.

Tools are certainly noble. To build guitars and cameras and a thousand other things artists need to do their work is important. And while there is artistry in some of those tools, they're not art. They're used by artists to make art. I work on WordPress.com, but I know it's a tool for writers and makers. As good as I think WordPress.com is, they do the heavy lifting: they rightfully put their names on their posts, not mine.

When I meet people who are passionate about technology, software or entrepreneurship, I realize how different I am in some ways. They are passionate about making tools and I share that passion. But above all I want to make first order, epic, amazing things. Novels, movies, stories, paintings, anything and everything. Things that deliver an experience, rather that the empty promises of salvation through productivity, the singular and empty promise driving most of the tools we make.

Your favorite books, movies, art, and music move you in ways that have nothing to do with productivity. On your deathbed your best memories will be playing with your kids and loving your family, entirely 'unproductive' acts. What are the real things in the world? The things that matter most? They are things no tool can give you – they are available to you all the time if you choose them and no tool can choose the important choices for you.

The questions I ask are: what can I make that reveals the world? Or the world as it should be? What do I know or can share from deep inside, through a craft, to be meaningful to others? The only answers to these questions are through art, or art like projects. They demand more of myself than I could possibly contribute to a software project or a startup company. To do truly epic things requires a different medium.

The term sui generis means work of its own kind. I take the term to mean work that is personal and demanding, that requires you to reveal things you are afraid to reveal. How you feel about the world, or yourself, or a thousand interesting things we rarely express. Writing down your deepest fears, secret regrets, or deepest desires, might not garner much interest from the world, but it will be more epic for you than dozens of the million download product launches you fantasize about. It will certainly be epic for you and a close friend (or perhaps a room full of strangers?) you share those thoughts with. Epic work comes from making a deeper connection to who we are, and finding a medium to express it well to others. A tool can never be that medium. Therefore software is not epic.

——————————–

Thanks to @msamye who when I mentioned the idea for this essay, said she'd like to read it.

Related posts:

The bias of social software

Why software sucks: an essay

Need a new writing tool: help?

More on why software sucks

Top 100 blogs for software developers

March 21, 2012

How to become a motivational speaker

I get asked about this often. Most of the news here isn't good.

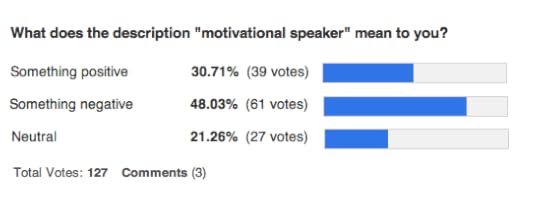

There is a stigma around the phrase "motivational speaker". The stereotype is a preacher or a snake oil salesman, all promises and slickness, delivering little substance. Or infomercials that promise if you just read this book, or follow this program, you'll get everything you heart desires.

I did a simple poll yesterday and the results match my assumptions. Of course, readers of this blog might share my biases and a survey done to a wider audience might return different results (Also, we could compare the results here with the results for "public speaker").

In practice, when I speak, I'm trying to motivate, but that's true of all teachers and speakers. I don't know any demotivational speakers (although some bosses have this ability, intentionally or not). If you see a teacher or speaker on any subject, everyone knows his or her goal is to give you insights or inspiration to do something. All speakers of all kinds have the intent to motivate.

To motivate someone in the abstract, which is what a "motivational speaker" is asked to do, is odd. George Carlin also found it strange. To paraphrase him: "if you have the motivation to go to a seminar, why not use that motivation to go do the thing the seminar is telling you to do instead of sitting there listening?" No one can give you real motivation: you have to generate it yourself. The inspiration you feel because of someone else won't last long after they leave: you need to cultivate your own motivation to achieve what you want in life. (Wait, do I sound like a motivational speaker now?). Whenever I'm asked to be motivational, I'm sure to address this paradox.

I'm a good and inspiring speaker, but I know the limitations. A great lecture can only do so much. Unfortunately, many "motivational speakers" make claims as if they don't, promising much to many people with real problems, earning a negative and cheesy stigma (See I live in a van down by the river). Perhaps motivational speakers aren't the problem, it's the impossible promises some of them make.

Folks like Tony Robins, largely taking up the can-do attitude of Dale Carnegie, do often offer good advice and genuinely seems to care about helping people. But that's not always the case. And somehow its people who are interested in being motivational speakers who don't seem to be aware of the stigma around that moniker.

Overall, when people say "I want to do motivational speaking" they just mean "speaking". They want to be hired to go places and talk about things.

Here is the advice I have:

1. There is a demand problem, not supply. The world is filled with people who believe they have a good story to tell and can motivate others. This means the market is a demand market, not a supply market. Unless your particular story has great appeal, say perhaps because you won five gold medals at a recent Olympics , or you've been on a spate of talk shows lately, there is no demand for you. Your primary problem is to find audiences where there is some demand. This is likely in your profession, your neighborhood, or anywhere that you particular story makes you credible and interesting. You don't instantly generate demand. You grow demand, starting with a niche where you are known and respected, and grow from there. This also means you won't be paid for awhile. Pay comes with demand.

2. Demand is based on perception, not talent. Motivational speakers are typically hired because of their story, not because of their speaking or storytelling ability. This is counterintuitive, as it means people are hired not for the skill itself, but for people's perception. It's perhaps unfair, but we are not a rational species. More people will come to hear Lady-Ga-Ga give a talk about the life story of Scott Berkun, than will ever come to hear Scott Berkun talk about Scott Berkun.

3. There is a road but it's slow and filled with work. There is no singular speaking circuit. The way to get asked to speak at places is to be seen speaking in other places and do a good job. Or get a video of yourself doing a good job, and make sure that organizers of other events get to see it. Many would-be speakers see books as the way to get credibility for speaking, which is both true and odd. If you write a good book that becomes popular, it can help you generate demand and credibility, but most people writing books for purposes other than writing books don't write good books.

4. You will be hired for expertise first. The first speaking engagements you get will be in fields or about specific skills. If you were a sports star, you'll find it easier to get asked to speak to high school athletes. If you're a journalist, you'll find it easier to speak to journalists or people studying journalism. Look for events about an expertise you have and start there. You'll have more credibility with audiences that share, or at least respect, your specific background.

5. The good news: earning credibility for talented hard working people is easier than ever. And building an audience is easier than ever in history. Between a blog (free), a youtube account (free), facebook and twitter feeds (free) and cell phone with a video camera (free-ish as you already have one), you can start right now showing your abilities and building interest in your ideas and talents. But there is no shortcut and there are many people in the race. It takes time to build a following, and to earn a reputation sufficiently good to have people come looking for you. Your best advantage is your community and network, who if properly motivated (ha ha) can help you spread word of your talents.

For more on the business of public speaking, read Why Speakers earn $30,000 an hour, a free excerpt from my bestseller, Confessions of a Public Speaker.

Related posts:

What does "motivational speaker" mean to you?

How much to charge for speaking?

Stupid things presenters do (and how to stop them)

Confessions of a Public Speaker

Creativity: Supply vs. Demand

March 20, 2012

March 18, 2012

On Writing vs. Speaking

Paul Graham wrote recently on his perspectives on the written vs. spoken word.

Graham admits he's more confident as a writer than a speaker. This biases his comparisons and his essay. He'd have benefited from talking to people who he thinks are both good speakers and good thinkers (and perhaps good writers) as they'd have the balanced perspective he admits he does not have. He writes:

Having good ideas is most of writing well. If you know what you're talking about, you can say it in the plainest words and you'll be perceived as having a good style. With speaking it's the opposite: having good ideas is an alarmingly small component of being a good speaker.

Most writers are unable to write in plain words or unable to find good ideas. Why? I don't know, but it's harder than Graham suggests for most people on this planet to do. Graham has ideas and does write well in a simple style, but he's assuming most people can do it because he can. Read the web for an hour: this is not the case. It's splitting hairs to argue over whether there is more bad writing or bad speaking on planet earth since there is so much of both.

Speaking is harder in many ways than writing because it is performance. You have to do it live. Some people who do not like to perform try to do what Graham does: they try to memorize their way through it, which doesn't work. You tend to fail when using a method for one form in another form. Performance means there is no undo and no revision, which is a huge part of the appeal of seeing bands and people do things live and in person. It's why I'm paid more as a speaker than I am as a writer: the same was true for Mark Twain, Charles Dickens and even David Sedaris or Malcolm Gladwell.

Writing is harder in some ways than speaking. Writing must be self contained: there is no body language or vocal emphasis as everything must be in the words themselves. But the ability to revise and edit dozens of times narrows the gap. With enough work you can revise your way into competence. Yet speaking is performance: there is no revision of an event. You can perform it again to improve on mistakes, but each instance must be done every time. When you finish an essay, it is done forever.

Graham writes:

With speaking it's the opposite: having good ideas is an alarmingly small component of being a good speaker. I first noticed this at a conference several years ago. There was another speaker who was much better than me. He had all of us roaring with laughter. I seemed awkward and halting by comparison. Afterward I put my talk online like I usually do. As I was doing it I tried to imagine what a transcript of the other guy's talk would be like, and it was only then I realized he hadn't said very much.

This confuses entertainment with expression. Popular writing can be similarly hijacked – look at twitter and the web – all media has this problem. There are different tricks to use in each form, but an essay can make you laugh, or make you angry, or make you hit the Facebook like button, despite not saying much, or anything at all.

I do agree with Graham that some speakers and "thinkers" are popular solely because they are likable and entertain, or infuriate and inflame. But this is a failing of all mediums, including writing.

Graham continues:

A few years later I heard a talk by someone who was not merely a better speaker than me, but a famous speaker. Boy was he good. So I decided I'd pay close attention to what he said, to learn how he did it. After about ten sentences I found myself thinking "I don't want to be a good speaker." Being a really good speaker is not merely orthogonal to having good ideas, but in many ways pushes you in the opposite direction.

Wow.

Emerson, Gandhi, Churchill, MLK, Jesus, Socrates, Lincoln, Mandala. These are a handful of great thinkers who used speaking as a primary medium of expression.

It's true that much of what some of them spoke was heavily written before it was spoken, but the world experienced these ideas first as spoken words.

I have to stop here to acknowledge that the history of thinking was spoken. The Ancient Greeks, where many of our big ideas still come from, talked. Writing as a primary way to express ideas wouldn't arrive for 1500 years. Talking and thinking have a much older relationship than writing and thinking. That doesn't mean speaking is better – writing has many advantages – but to sweep speaking aside is foolish, and reflects Graham's bias more than his wisdom. Many ideas at many startups are discovered, shared and developed through spoken words. Pitch meetings, arguments at whiteboards, late night hacking sessions, discussions over lunch: it's heavily spoken word. Life is mostly spoken, not written.

Graham continues:

The way to get the attention of an audience is to give them your full attention, and when you're delivering a prewritten talk your attention is always divided between the audience and the talk—even if you've memorized it. If you want to engage an audience it's better start with no more than an outline of what you want to say and ad lib the individual sentences.

This is where Graham, whose work I admire, makes a big mistake. He has admitted he's not a good speaker and doesn't like the form. Why then does he feel qualified to give advice on how to do it well?

In my bestseller The Confessions of a Public Speaker I carefully explain audience attention depends on answering questions they came to hear. The majority of speakers fail at this, focusing on what they themselves wish to speak about, or what their slides will look like, rather than their audience. Speaking, like writing, is an ego trap. It's not about you, it's about them: what questions do they want answered? What stories did they come to hear? If you understand why your audience showed up at all, and deliver on it, you will keep their attention. Graham's advice is all about the speaker, but that's the common tragedy – it's not about speaker. A speaker who studies the audience and puts together content that addresses their interests will always do well. They're rare.

Before I give a talk I can usually be found sitting in a corner somewhere with a copy printed out on paper, trying to rehearse it in my head. But I always end up spending most of the time rewriting it instead.

I would never do this. I stay up late the night before, if needed, to finish preparing. I practice the talk several times, revising if needed, until I'm comfortable. This comfort allows me to be fully present with an audience and not worried about my knowledge of my own material. This is also how I ad-lib or change directions based on a live audience. My preparation gives me the confidence to make adjustments. An hour before my talk I'm not thinking much about my talk at all.

I do agree with Graham in some ways. I do prefer writing at times. But unlike Graham, I love both forms. I know I become a better writer every time I speak, and become a better speaker every time I write.

—————————

Related: An open letter to speakers, which gives specific practical advice on speaking.

Related posts:

Is speaking easier than writing? Some advice

Essay: Writing hacks (hacks on writing), Part 1

Speaking at Web 2.0 expo April 21-25th

Need a new writing tool: help?

Daily writing plan

March 17, 2012

On Truth, Daisy and This American Life

The news: Mike Daisy presented a story from his one man show about Apple's labor practices as journalistic fact to This American Life (TAL). It was a mistake. Daisy has apologized and This American Life spent an hour this week explaining what happened and why.

One popular and superficial response is: truth is binary and lies were told, and everyone should be ashamed.

This is a convenient and useless reponse. It dodges the tough, sloppy truth about truth lurking in this story about stories.

In the Coen brothers film Fargo, the opening titles say "Based on a True Story". This is not true.

In the move Apollo 13, based on an actual true story, Gene Kranz, the actual flight director, is shown in the film saying "Failure is not an option". He never actually said this.

While we know movies are entertainment, how much of the world do you know mostly from movies at TV shows you have seen? You know it's Hollywood, but yet much of what you think about history, or life in general, might very well come from entertainment, rather than truth. I'd guess most adults consume more works of fiction than non-fiction across all media in their lifetimes. If so, do we base most of our lives on fiction? Is that good? Bad? Neither?

Look at your resume. Is it true? Is it the same truth your coworkers and bosses would write about your work history? Do you gloss over things? Combine facts from different events? Leave important events that don't fit the story you want to tell out? Sure, you are not a journalist, but what ethical responsibility do you have in your own writing about your own life to a potential employer?

I'm not advocating lying. What Daisy did on This American Life (and apparently on other shows) is wrong. He had every chance to express what license he took as a performer in his storytelling, and making a distinction between art and reporting.

Instead I'm saying most of what we offer each other as truth is only partially true, and partially untrue, since we don't include all of the truth. If your resume included all of the truth in an accurate and unmanipulated form, it would be infinitely long. We look to the skill of storytelling as a tool to compress and shape the truth to effectively convey something. In studying the history of history, or the history of facts, its clear what defines a fact is messy. There's never a singular truth. Like the film Rashomon, truth is like a diamond with many facets and angles, each true in its own way: American history reads very differently if written from the perspective of the native Americans. The history of the enlightened ancient Greeks reads differently if told by their slaves.

Journalists have stricter rules about truth than filmmakers and artists, but they fall victim to similar challenges. They want their stories to be read and books to be sold. The headlines they use on websites or covers of magazines are sensational more than truthful. And even if profit were not a motive, no person is objective. Before the most noble journalist in the world takes on a story, they have their own hidden biases and points of view that are impossible to eliminate. The line of ethics is when a journalist knowingly denies due diligence on checking facts and betrays the reader's trust – or discovers after the fact a betrayal has been made and fails to work to correct the mistake.

Many journalists, organizations and bloggers bury these mistakes. They report them days later in minutia and footnotes. Or they never bother to look for or report them at all.

This American Life's entire episode documenting the problems with their own reporting should be commended for making clear the errors that were made and accounting for them. I can't think of the last time a major network, newspaper, or TV show spent an entire episode explaining how they messed up. This American Life should, of course, also be criticized for making the mistakes in the first place. But shock and outrage about it are naive - it wouldn't be hard to find similar errors of fact in stories reported every day, as CNN, FOX, MSNBC. blogs and twitter report stories so fast that fact checking is impossible. Skepticism of all news is warranted, especially news reported as fast as technology allows – it will unavoidably contain errors, both intentional and not.

Mike Daisy identified his primary mistake – he should never have expressed his story as journalism. And This American Life should never have accepted it as such.

In the end 3 things were true before this, and are true now:

Mike Daisy is a fantastic performer and his shows are moving, powerful and good works of art.

Apple is a great company that has had well documented labor issues.

This American Life is an excellent program that for years has set a high standard for amazing, quality works of reporting, non-fiction storytelling and journalism.

The recent scandal changes none of these things. Yes, Daisy's and TAL's reputation are worse and Apple's is better, but not significantly. Not to a skeptic.

Writing and reporting of any kind have risks. The best lesson here is to remind us all as readers and consumers to always ask questions of what is true, regardless of the source.

No related posts.