Scott Berkun's Blog, page 47

January 8, 2013

The three things you always have

You always have three things. The three things are your answers to these questions:

What happened?

How you feel about it?

What are you’re going to do next?

It’s common to confuse #2 with #3. Some people get stuck on the feelings for the past and never move on.

Feelings are important as that’s how we know who we are. Venting, dwelling or celebrating serve the purpose of being present with how we feel. But after a day, a week, or a month, you have to recognize feelings aren’t actions. Only if a feeling is converted into a decision, even if it’s just the decision to share the feeling with someone, can it impact the future. Even if your situation is ‘life is awesome’, the answer to #3 might be ‘figure out how to keep this going’ or ‘tell my friend who wants me to be happy how happy I am’.

For example, lets pretend I was attacked by a gang of wild terrorist bears:

What happened: I was attacked by wild terrorist bears.

How you feel about it: sad, scared and angry. And somewhat dead.

What you’re going to do next: stop running naked in a suit made of beef hot dogs, which terrorist bears are known to love to eat, at the terrorist bear exhibit at the zoo.

There you go. #3 leads to an action that leads to a new set of three things. That is of course if you’re not dead. If you’re dead you have precisely zero things. Be glad you have at least three more things than dead people do.

And to conclude, here’s my three things:

What happened: I wrote this post.

How do you feel: Glad someone is still reading this.

What are you going to do next: Wait to see if you leave a comment. I’ll give you a suit of hot-dogs if you do.

Next book to be published by Wiley / Jossey-Bass (with FAQ)

My upcoming book on my year at WordPress.com will be published with Jossey-Bass. I signed with agent David Fugate, who helped negotiate a fine deal with them. We had a few offers, but after talking with editors Genoveva Llosa and Susan Williams at JB I was convinced they’d be great partners to work with on this book.

Jossey-Bass is the business imprint for Wiley: they’ve been responsible for 13 of the top 25 business books last year (as well as other classics like Lencioni’s The Five Dysfunctions of a Team).

Frequently asked questions:

Why didn’t you self-publish? I considered it. If I could I preferred to find to a publisher that could help bring the book to a wider business audience than I could alone. I’m hoping I can connect directly with the WordPress community and my own audience about why they’ll want to read the book. But for the truly general business audience, beyond just the tech sector, my reach is limited. Jossey-Bass’s track record can help there. Working with a publisher again is also a chance to learn some new tricks.

Why did you get an agent? I’d looked for agents before, but never found one that I liked and who was interested in the book I was working on. Both of those things changed when I talked with David. I managed to get offers on the book myself but he helped look for others, advised me on the book proposal, and took over negotiation and contract details, which I was happy not to have to do myself for once.

Why didn’t you go with O’Reilly? I did talk with them, but for the same reasons in #1 they weren’t the ideal choice for the book, as their reach, while much greater than mine, hits the same tech-business crowd I can reach myself. I think they’re an excellent publisher and I bet I work with them again.

More on the book soon. I’m on the homestretch of the first draft and hope to be finished within the next two weeks.

If you have other questions, leave a comment.

January 7, 2013

Best of Berkun (my best posts of all time)

I’ve written 1400 posts over 11 years.

In 2011 I published Mindfire: Big Ideas for Curious Minds, a collection of 30 of my most provocative essays.

The list below is wildly more comprehensive: it covers all my work published online across all categories. Hope you find things you enjoy. Please subscribe or follow to get more good work as it’s published.

Creativity

How to be Creative: the Short Honest Truth

Creative Thinking Hacks* (video)

Why You Get Ideas in The Shower

How to be a Genius

How to Pitch an Idea*

How to Survive Creative Burnout*

How to run a Brainstorming Meeting

Idea Killers: Ways to kill ideas and countermeasures

Ideas vs. Time

John Cleese On Creativity (with notes)

Innovation

Good beats ‘Innovative” nearly every time

Innovation vs. Improvement: How do you know what you have?

Stop Saying Innovation / Why Jargon Feeds on Lazy Minds

Where do Your Ideas Die?

How to Diagnose Creative Failures

How to Innovate Right Now

The 5 Best Books on Innovation EVER

Inside Pixar’s Leadership

The Simple Plan: My speech at The Economist

9 Ways to Understand How Ideas Spread

The Idea Approval Index

The Secret About Innovation Secrets

Writing

How to Write a Book – the short honest truth

How to Write a Book, part 2

Is Your Book Idea Good? Yes, I promise

On Insecurity and Writing

Why you Fail at Writing

Writing Hacks Part 1: Starting

How to write 1000 words (video)

How to Find Your Voice

Confessions of a Self Published Author

How to Start Writing a Book

Life Philosophy

The Cult of Busy*

How to Learn From Your Mistakes*

How to Be a Free Thinker*

How to Give and Receive Criticism*

Book Smarts vs. Street Smarts*

How to Stay Motivated*

Attention and Sex*

How to Make a Difference*

Hating vs. Loving*

The Three Piles of Life

Why It’s OK to Be Obvious

How to Be Good At Anything

Should You Always Trust Your Gut? (NO)

How to Discuss Politics with Friends

Working Life

How to survive a bad manager

Why You Must Lead or Follow*

Why Smart People Defend Bad Ideas*

Ten Reasons Managers Become Great

Ten Reasons Managers Become Assholes

Advice for New Managers

How to Manage Smart People

How to Convince Anyone of Anything

An Open Letter to Micromanagers

How to Call Bullshit on a Guru

Why Do Big Companies Suck?

How to Keep Your Mouth Shut

Experience is Overrated

Interface Design / Making Software

The Myth of Optimal Design

The Myth of Discoverability

The Top Mistakes UX Designers Make

Why Software Sucks

How to Run a Design Critique

5 Dangerous Ideas for Designers

Software is Not Epic

The Future of UI Will Be Boring

Why Ease of Use Doesn’t Happen

Asshole Driven Development

Project Management

Why Project Managers Get No Respect

Are You a Leader or A Tracker?

How To Fix A Team

How to Make Things Happen

What To Do When Things Go Wrong

How to Stop Over-communication

How To Start Meetings on Time

Public Speaking

How to Prepare: A Checklist for Great Talks

How to Fix Boring Lectures

How to be Passionate

The Attack of the Butterflies (how to overcome fear)

An Open Letter to Speakers

An Open Letter to Conference Organizers

How to Give a Perfect Demo

How To Speak to A Bored Audience

Why Panel Sessions Suck and How to Fix Them

How to Get Paid to Speak

The Myth of the Tough Crowd

Posts marked with * appear in Mindfire: Big Ideas for Curious Minds.

Did I miss a post you think belongs here? Leave a comment.

Good Beats Innovative Nearly Every Time

[This post originally published on BusinessWeek]

One troubling phenomenon is the push for everyone to be innovators. I suspect more books have been sold with the word innovation in their title in the last 10 years than in the previous 50, including, I confess, one of my own. And while much has changed, it’s hard to say the quality of things in the world has improved as fast. Keen-eyed consumers bemoan the low quality of many of the things we buy and try to use. Web sites divide short articles across 25 ad-filled pages. Gadgets quickly run out of power. Smartphones have anemic reception or fragile screens. Many things we buy and use never work in the way we’re promised, which suggests there are opportunities in merely being good: Much of what’s made falls short of that mark.

From my studies of the history of business innovation, I’m convinced you can beat competitors and even dominate markets without fancy tricks. All you need is the ability to make things that are good consistently, since few companies do.

While we’re fond of trumpeting the praises of Apple, whose iPod revolutionized music, we forget how dismal the competition was. It was not a field of masterpieces; it was a motley crew of ugly, clunky, painfully hard-to-use devices. Apple applied basic design sense to an immature field at a time when the world was ready for something better. Firefox, which rekindled innovation in Web browsing, arose from Microsoft‘s near abandonment of its Internet Explorer browser after the browser war with Netscape ended [Disclosure: I worked on IE 1.o to 5.0]. Their version 6.0 release was a major step backward, opening the door for someone to win by merely providing something good, which Firefox did in 2004. Google was launched a decade after the invention of search engines; Amazon was not the first online bookstore. But they were both the first to do a good job at selling their good services for a good profit. In retrospect, their successes seem amazing, but at the time, the goals were simple and the objective humble and clear: Be good, or at least better than the other guys. For they knew that alone was hard enough.

Loose Usage

The word “innovation” is used to mean many different things, which is part of the problem. Executives and consultants throw it around like magic dust, hoping to cover their ignorance of why products and companies have done well or failed. But it’s clear most companies fail not because of their lack of inventiveness; it’s their lack of basic competence. Most leaders fail to prevent bureaucracy, hubris, and too many cooks from killing good ideas before they ever get a chance to make it out the door, resulting in the mediocrity we know too well.

Innovation, in the simplest definition, means new or novel, to take an approach others have not seen before. But by this definition, the iPod and Firefox barely qualify. Even the iPad is late in the game of tablet computers, as Microsoft’s Tablet PC and Amazon’s Kindle have been aiming at this market for years. In all cases, these are entrants into fields of established players. Their creators borrowed parts and ideas from other products and even from other companies. Their success or failure is driven less by revolutionary ideas or radical disruptive breakthrough thinking and more by a focus on making solid, reliable, simple, good products that solve real needs people have.

If your competitors are mediocre, the merely good can seem exceptional. All things being equal, in a battle between a good product and an innovative one, the good one will usually win. The makers of the good are less worried about abstract perceptions of how novel they are. Instead, they focus on results, caring less about whether the ideas involved are new, old, or recycled. Those obsessed with innovation contract the disease of hubris, ignoring many good ideas because they have been used before. They forget that an old idea cleverly reused, or borrowed from a different field, will be new to the world. Most projects aimed at innovation fail because creators become distracted by their egos from the true goal: to solve real problems for real people.

Solving a Problem

If you insist on doing something new, take this advice: Start with the important problems your customers, or your competitors’ customers, have and try to solve them. If conventional approaches fail, you’ll be forced to invent and be creative as a side effect of your goal. If you ask the creators of so-called breakthrough ideas, this is a common reason they found those breakthroughs in the first place. Their ambition wasn’t to be called an innovator. They weren’t planning to be disruptive or game changing. They merely had a tough problem to solve on their way to beating the competition in the forgotten practice of simply making better things.

Making better things is difficult enough. Learn to do that well, and when you’re done, and your customers and stockholders love you, the label “innovator” will magically land next to your name.

January 4, 2013

The amazing invention of Braille

While studying to write the Myths of Innovation I read hundreds of accounts of how world changing inventions came to be. While many of those stories are in the book, there are hundreds more worthy of telling.

While studying to write the Myths of Innovation I read hundreds of accounts of how world changing inventions came to be. While many of those stories are in the book, there are hundreds more worthy of telling.Today is the birthday of Louis Braile, one of the inventors for the amazingly clever system of writing for the blind.

For all you designers and engineers out there, language design is extremely hard. Languages have to be efficient, robust, precise, easy to learn and fast to use. Spend a minute considering how hard it is to create a language: can you make a better alphabet? (this was once an interview question at Microsoft).

Braille represents a fascinating combination of engineering, linguistic, and interaction design, all for a high frequency critical task.

The story of the invention of Braile goes back to Napoleon and his desire to find a way for soldiers to communicate at night, silently, without light. A captain in the army named Barbier developed a system called night writing, but it was rejected as being too complex to learn and use. Louis Braille either met Barbier, or learned of his ideas, in 1821. In 1824, after years of work, Braille developed critical simplifications to the design, including moving from 12 dots to 6 per character. At first the system was used to literally translate each character, but as its use spread unique shorthands and contractions were added. Louis Braille was only a teenager when he finished the system, publishing it in 1829 and a revised, further simplified version in 1837.

His own school didn’t adopt the system until 1854, after his death. The system slowly gained adoption in Europe and America (1916).

Prior to this system most blind schools in France used something called a Tactile alphabet, with letter forms were printed raised on the paper. Louis Braille learned this system as a child. These were expensive to print, heavy to hold and clumsy to use.

The invention of the typewriter has some connections to Braille, as Pierre Foucault, a former student at Braille’s school, had an early prototype for a typewriter that printed Braille in 1847.

Technically Braille is the first system of digital writing, since the letters are encoded and can be manufactured and stored or printed mechanically. It is not a universal language however, as the encodings typically translate letters, demanding the reader know the language they are written in (see International Braille, which explains how in 1878 they standardized some elements for Braille across languages).

With the rise of screen reading software the use of Braille is in decline. But it remains a stellar example of design and invention.

Quit your whining

Whatever your excuses are, these guys can’t hear you because they’re busy living.

From Sports Illustrated Top 100 Photos (Photo by AP).

January 3, 2013

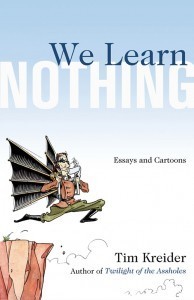

We Learn Nothing: Book Review

I love books comprised of essays as they free writers to go in a wide range of directions and styles, unhinged from the burden of a single narrative theme. When I heard Nancy Pearl mention it offhand in her list of the year’s best books, I picked it up (its actually the first book I’ve purchased because of Pearl – I don’t listen to her regularly, and it just happened to be the first essay collection I’ve heard her mention).

I love books comprised of essays as they free writers to go in a wide range of directions and styles, unhinged from the burden of a single narrative theme. When I heard Nancy Pearl mention it offhand in her list of the year’s best books, I picked it up (its actually the first book I’ve purchased because of Pearl – I don’t listen to her regularly, and it just happened to be the first essay collection I’ve heard her mention).

The book We Learn Nothing, by cartoonist and essayist Tim Krieder, has some of the sharpest, most insightful writing about people, life and politics I’ve read in some time. I’m not familiar with his cartoons (the book explains he was a liberal critic of the G.W. Bush administration), but I did very much enjoy this book.

Many of the essays explore questions about life through the filter of his own, using his friends, his career, and his family as the landscape for asking and answering questions we all have. His writing is sharp, intellectually provocative, and at times funny, even charming. The format of the book lends itself to a certain egoism as he is a central character in many of the essays, and many of the cartoons (the book is mostly essays, with the occasional series of drawings).

Here are some choice quotes from the book:

On our deepest secrets and our friends:

Each of us has a Soul Toupee. The Soul Toupee is that thing about ourselves we are most deeply embarrassed by and like to think we have cunningly concealed from the world, but which is, in fact, pitifully obvious to everybody who knows us. Contemplating one’s own Soul Toupee is not an exercise for the fainthearted. Most of the time other people don’t even get why our Soul Toupee is any big deal or a cause of such evident deep shame to us but they can tell that it is because of our inept, transparent efforts to cover it up, which only call more attention to it and to our self-consciousness about it, and so they gently pretend not to notice it. Meanwhile we’re standing there with our little rigid spongelike square of hair pasted on our heads thinking: Heh—got ’em all fooled! What’s so ironic and sad about this is that the very parts of ourselves that we’re most ashamed of and eager to conceal are not only obvious to everyone but are also, quite often, the parts of us they love best.

On the addictive nature of complaints:

It seems like most of the fragments of conversation you overhear in public consist of rehearsals for or reenactments of just such speeches: shrill, injured litanies of injustice, affronts to common sense and basic human decency almost too grotesque to be borne: “And she does this shit all the time! I’ve just had it!” You don’t even have to bother eavesdropping; just listen for that unmistakable high, whining tone of incredulous aggrievement. It sounds like we’re all telling ourselves the same story over and over: How They Tried to Fuck Me Over, sometimes with the happy denouement: But I Showed Them! So many letters to the editor and comments on the Internet have this same tone of thrilled vindication: these are people who have been vigilantly on the lookout for something to be offended by, and found it. We tend to make up these stories in the same circumstances in which people come up with conspiracy theories: ignorance and powerlessness. And they share the same flawed premise as most conspiracy theories: that the world is way more well planned and organized than it really is. They ascribe a malevolent intentionality to what is more likely simple ineptitude or neglect.

Most people are just too self-absorbed, well-meaning, and lazy to bother orchestrating Machiavellian plans to slight or insult us. It’s more often a boring, complicated story of wrong assumptions, miscommunication, bad administration, and cover-ups—people trying, and mostly failing, to do the right thing, hurting each other not because that’s their intention but because it’s impossible to avoid. Obviously, some part of us loves feeling 1) right and 2) wronged. But outrage is like a lot of other things that feel good but, over time, devour us from the inside out. Except it’s even more insidious than most vices because we don’t even consciously acknowledge that it’s a pleasure. We prefer to think of it as a disagreeable but fundamentally healthy reaction to negative stimuli, like pain or nausea, rather than admit that it’s a shameful kick we eagerly indulge again and again

On the sad commonalities of political parties:

The truth is, there are not two kinds of people. There’s only one: the kind that loves to divide up into gangs who hate each other’s guts. Both conservatives and liberals agree among themselves, on their respective message boards, in uncannily identical language, that their opponents lack any self-awareness or empathy, the ability to see the other side of an argument or to laugh at themselves. Which would seem to suggest that they’re both correct.

It was one of the best written books in terms of insight and style I’ve read in some time. Get the book here: We Learn Nothing.

Nexus: a sci-fi novel of a post-human future

My friend Ramez Naam’s first novel, Nexus, just released and it’s getting great reviews. I haven’t read it yet, but here’s some of the feedback it has earned so far:

My friend Ramez Naam’s first novel, Nexus, just released and it’s getting great reviews. I haven’t read it yet, but here’s some of the feedback it has earned so far:

Wired says “Good. Scary good… stop reading now and have a great time reading a bleeding edge technical thriller that is full of surprises.”

The Wall Street Journal says “Provocative… A double-edged vision of the post-human.”

Cory Doctorow at BoingBoing says “Nexus is a superbly plotted high tension technothriller… full of delicious moral ambiguity… a hell of a read.”

Ars Technica says “Nexus is a lightning bolt of a novel… with a sense of awe missing from a lot of current fiction.”

You can read more about it at http://rameznaam.com/nexus or get it from amazon: http://amzn.to/WkHgbh

December 28, 2012

Great talk: Life on a Möbius Strip

One reason I rarely get excited about TED talks, although I do enjoy many of them, is I’m drawn towards the personal. For years I’ve been a bigger fan of the MOTH podcast, which is an evening of stories told without notes in from of live audiences. Although these talks are generally well presented, the agenda is different. They’re not as shinny. They have rough edges. They’re human and humble and honest in a way people pitching ideas can’t quite match.

A recent gem of a talk in every way is this one by Janna Levin, theoretical physicist and author of How the Universe Got Its Spots.

The talk moves from astrophysics, to misguided love, and the consequences of taking big risks.

It’s called Life on a Möbius Strip – you can listen to the podcast here like I did, or you can watch it:

December 24, 2012

Mind over mind: book review

Why do great players sometimes choke in key games? How do scientists explain the placebo effect, where merely believing in something makes it real? These questions about our minds and how they help and hurt our ambitions are explored in Chris Berdik’s new book, Mind over Mind: the surprising power of expectations.

Why do great players sometimes choke in key games? How do scientists explain the placebo effect, where merely believing in something makes it real? These questions about our minds and how they help and hurt our ambitions are explored in Chris Berdik’s new book, Mind over Mind: the surprising power of expectations.

The good news is Berdik excels at summarizing research studies, and he keeps his aim sharp. He focuses on various ways our expectations of things impact the results, from performance in sports, to medical treatments, to addiction. The key element in our psychology is anticipation and being able to manipulate what we anticipate.

Some of the studies I’d read about before, but there were many inquiries into placebo and sports psychology that were new to me, and memorable. The long uncomfortable relationship between science and placebo has some entertaining origins, which Berdik explores early on, and returns to at the close of the book. He closely examines the wild word of wines, and the circular relationships between what we’re told about wine and what we experience when we drink them.

I read the book in two sittings, over several hours, which is in many ways the best review I can possibly give. Towards the middle the focus on reporting on research dragged thin, but the closing chapters were strong and returned to the core theme of examinations of placebo.

I’d recommend Mind over Mind it to anyone trying to better understand their own habits, and the latest scientific understanding of how our brains and psychology help and hurt us in trying to live the lives we desire. The book isn’t structured around how-to advice, but there are plenty of lessons in each chapter that clarify erroneous beliefs about how our beliefs work, which if nothing else will lead to great conversations with your doctors, trainers and partners.

Some choice quotes:

On the useless and pretensious vocabulary wine reviewers use:

“the economist Roman Weil gave everyday wine drinkers a triplicate test—three glasses but only two wines, with one repeated. He also gave them descriptions of both wines written by the same critic to see if they could match words with wine. About half of the subjects could tell the two wines apart, which is somewhat better than chance. But among these folks who presumably had the keenest palates, only half correctly matched the wines with the critic’s descriptions. They would have done just as well by flipping a coin.”

About a study examining if chimpanzes evaluate quality the same ways we do:

There may be a good evolutionary reason for some irrational consumer behaviors, but when it comes to inferring quality from price tags, that’s all us.

On the near miss phenomenon among gamblers:

“…gambling addicts are suckers for the “near-miss” illusion—a lotto number off by one digit or a slot machine jackpot spoiled by the final spinner. Instead of seeing these outcomes as losses and feeling the normal, discouraging sting, addicts interpret them as encouraging signs that they’re mastering the game, or that luck is turning their way. They bet even more. The gambler’s perverse pleasure in the near-miss is based in a hardwired cognitive reflex. Our future-oriented brains habitually seek out patterns, because they help predict what’s coming next. Finding a pattern is like solving a little puzzle. Aha! Now we know what to expect. Our reward system gets pumped.

Our brains are so pattern happy that they find patterns even when we know they don’t exist. When people in brain scanners are explicitly told they’ll be watching a randomly generated series of squares and circles, their prefrontal and reward centers still react to runs of several squares or circles in a row, or a long sequence of alternating square, circle, square, circle, square. The gambling addict’s brain takes this reflex to an extreme. In the mind of a compulsive gambler, chance has personality and purpose. Luck can be both wooed and mastered”

About a better framework for thinking about failure:

“Dweck has since made a lifelong study of how people deal with failure. She has found that having the right expectations about failure can be crucial to ultimate success. In her research, Dweck contrasts “entity theory,” which says success is largely determined by the extent of one’s natural talents, and “incremental theory,” which says people define their abilities and limitations through effort. For lay audiences, Dweck uses the friendlier terms, “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset.”

Get the book here: Mind over Mind: the surprising power of expectations.