James Gleick's Blog, page 6

December 10, 2012

Ada’s Birthday

Ada Byron, later Countess of Lovelace, was born 197 years ago, 10 December 1815, so it’s safe to say that many bicentennial preparations are already getting under way. What an unusual sort of celebrity she has become, after nearly two centuries of total obscurity. Let us remember: she was forgotten.

Today she is the Google Doodle:

For basic introduction, BrainPOP has a nice little movie. A tweeter has just alerted me to an “indie-rock steampunk musical.”

And to mark the day, here’s one letter of hers, from my book. She was a young woman, newly married, and she went to see a model of the new “electric telegraph” in London,

& the only other person was a middle-aged gentleman who chose to behave as if I were the show [she wrote to her mother] which of course I thought was the most impudent and unpardonable.—I am sure he took me for a very young (& I suppose he thought rather handsome) governess. . . . He stopped as long as I did, & then followed me out.— I took care to look as aristocratic & as like a Countess as possible. . . . I must try & add a little age to my appearance. . . . I would go & see something everyday & I am sure London would never be exhausted.

August 5, 2012

Autocorrect, Unexpurgated

For those who cannot live without @scarthomas, the full version of my Autocorrect piece is here.

June 3, 2012

Harald Bluetooth? Really?

I wrote this—Inescapably Connected—eleven years ago. There was no such thing as “iPhone.” Bluetooth and Wi-Fi were barely coming into view. The “Network” was rising all around. We sipped information through straws that were about to become wormholes.

Some of it has come true.

May 11, 2012

Meta Enough for You?

For the Annals of Recursion.

1. In The Information (pages 408–409, for those who wish to follow along) I mention a poet named Thomas Freeman, who lived from approximately 1590 to 1630. I say he is “utterly forgotten” and add that he doesn’t even have a Wikipedia entry.

I would never have heard of Thomas Freeman myself, if Anthony Lane hadn’t happened to discover him in the course of reviewing Sir Charles Chadwyck-Healy’s English Poetry Full-Text Database for The New Yorker. That was seventeen years ago, in 1995. (I couldn’t read Lane’s hilarious piece on line when I was working on the book, but you can now, here: “Byte Verse.”)

Lane was making the point that the opportunity to read 165,000 poems by 1,250 poets spanning thirteen centuries on four compact discs priced at $51,000 might be considered a mixed blessing. He quoted this couplet by the aforementioned Freeman:

Whoop, whoop, me thinkes I heare my Reader cry,

Here is rime doggrell: I confesse it I.

2. From time to time, since the book was published, I’ve had the opportunity to speak about it or read bits of it to live audiences. For example, I did this on Tuesday at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. I’ve had to mention, though, that “utterly forgotten” no longer applies: Freeman now has a Wikipedia entry, thanks to Lane—and thanks also (if you’re so inclined) to Sir Charles. The entry was created by a Wikipedia user called Tom Reedy on September 17, 2010.

As he was listening to my talk, my host at Berkman, Jonathan Zittrain, was apparently multitasking, because as soon as I finished he offered an update on the Wikipedia situation. The Thomas Freeman entry now refers back to The Information. Professor Zittrain read this aloud:

This incident was described by James Gleick as an example of how unprepared people were for the WWW to bring all of human literature to the tips of their fingers.

He continued (and by now people were laughing):

Gleick mistakenly states that Freeman is not mentioned on Wikipedia, although it’s possible that this very page was added as a response to Gleick’s anecdote.

To which I can only say, yes, that’s possible.

3. It seems that this reference to me was added last summer—to be exact, on July 24, 2011, at 2:31 in the morning—by a user called Alf.laylah.wa.laylah. The last, extra-recursive phrase (“although it’s possible that this very page was added as a response to Gleick’s anecdote”) appears to have been an afterthought, added at 2:32.

This is the sort of thing one can learn by studying Wikipedia’s readily accessible histories of the editing of its entries. Another thing I learned is that on March 7 of this year a user expanded the Thomas Freeman entry by adding the sentence, “He liked men.” Seconds later, a vigilant Wikipedia entity called Cluebot NG removed the new sentence on grounds of “possible vandalism.”

4. So now I’ve blogged about Jonathan Zittrain’s quoting Wikipedia’s mention of my book’s comment that Thomas Freeman lacked a Wikipedia entry.

Perhaps the loop ends here. Somehow I doubt it.

February 23, 2012

A Paradox? A Paradox!

In his wonderful new book Zona (“A Book about a Film about a Journey to a Room”) Geoff Dyer, who is interested—profoundly interested, I’d say—in the subject of boredom, mentions a voiceover remark that everything’s “hopelessly boring”:

a remark that makes one wonder how quickly a film can become boring. Which film holds the record in that particular regard? And wouldn’t that film automatically qualify as exciting and fast-moving if it had been able to enfold the viewer so rapidly in the itchy blanket of tedium?

A paradox. If a film becomes boring quickly enough—that’s interesting!

It reminds me of something … but what? Oh, yes. The paradox of the Smallest Uninteresting Number. What is the smallest integer about which there is nothing interesting to say?

I discuss this in The Information, in the chapter called “The Sense of Randomness”; you can see why there would be a connection between the admittedly not very scientific notion of “interest” and the possibly more significant notion of randomness. Does an uninteresting number have to be, in some sense, random? Sixteen is surely interesting, by virtue of being the fourth power of two.

Number theorists name entire classes of interesting numbers: prime numbers, perfect numbers, squares and cubes, Fibonacci numbers, factorials. The number 593 is more interesting than it looks; it happens to be the sum of nine squared and two to the ninth—thus a “Leyland number.” Wikipedia also devotes an article to the number 9,814,072,356. It is the largest holodigital square …

Anyway, thanks to Geoff Dyer, you can already see where this is heading. If you could find a boring number—a number about which there was nothing special to say—it would instantly become the Smallest Uninteresting Number. That would be interesting.

December 26, 2011

Babbage: a Birthday Postscript

Charles Babbage was born 220 years ago today—Boxing Day. Here is a little addendum for Chapter 4 of The Information, which contains a joint mini biography of the brilliant and misunderstood Babbage and the  brilliant and doomed Ada Byron.

brilliant and doomed Ada Byron.

This is due to Sydney Padua, an artist (“animator and cartoonist,” she says) in London, who is perhaps as enamored of Charles and Ada (and surely as knowledgeable) as anyone I know. She has uncovered a gem of a memoir, which I had not seen before: a small book titled Sunny Memories, containing personal recollections of some celebrated characters, by “M.L.”—Mary Lloyd—published in London in 1880 by the Women’s Printing Society.

A few lovely tidbits:

Babbage, interested in the subject of “opinion, public or private, for or against individuals”—yet lacking access to Google, Facebook, and Twitter—”collected everything he could gather in print about himself, and pasted it in a large folio book, with the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ in parallel columns …”

Late in his life, troubled by forgetfulness, he went visiting one day without his cards. “So he took a small brass cog-wheel out of his waistcoat pocket and scratched his name on it and left it for a card!”

He liked to tell people that his great invention, the Difference Engine (“or the Leviathan, as he called it”) would someday, if it could ever be finished, “analyze everything, and reduce everything to its first principles and so include future inventions, and in short almost supersede the human mind.”

“Oh, dear Babbage,” Sydney Padua says, “kindly, brilliant, and odd!”

Lloyd’s memoir can be found here, thanks to the Internet Archive. And Padua’s ongoing Babbage and Lovelace webcomic, here.

November 10, 2011

The Flinging of Notes

Anyone interested in the relations between men and women (or any number of other topics) can get great pleasure from the day-by-day online version of The Diary of Samuel Pepys. It’s a soap opera. Especially at this moment (9 November 1668)  and for the last few weeks (that is, 343 years ago).

and for the last few weeks (that is, 343 years ago).

If you’re not up to date, Sam’s wife caught him in flagrante with her 17-year-old maid, Deborah Willet. He wasn’t sure exactly how much she saw. At one point he confessed to the embracing but denied the kissing. Or the other way around.

In today’s episode, messages are exchanged:

Up, and I did by a little note which I flung to Deb. advise her that I did continue to deny that ever I kissed her, and so she might govern herself … and as I bid her returned me the note, flinging it to me in passing by. And so I abroad by coach …

The way my mind tends to ramble, what most fascinates me is the flinging of the note. This is the available technology for exchanging messages. No one is texting, “Need 2 C U, Deb!” I know, it’s obvious. But it’s not trivial.

When I was writing about Newton, I kept wanting to say: “By the way, dear reader, what if he’d had e-mail? What if he’d had a photocopier? For that matter, what if he’d had electric light?”

October 7, 2011

Una Macchina Automatica

Indirect and abstract by its very nature, the telephone now seemed to be the positive symbol of my own situation: a means of communication which prevented mefrom communicating; an instrument of inspection which permitted of no precise information; an automatic machine, extremely easy to use, which nevertheless showed itself to be almost always capricious and untrustworthy.”

—Alberto Moravia, Boredom (1960)

October 2, 2011

Defining Information, Even More

Here is a scholarly paper that caught my eye. It appears in the latest issue of the journal Information; the title is “Naturalizing Information”; the author is Stanley N. Salthe, a professor emeritus of biology from Brooklyn College. It attempts to create a better-than-ever, all-purpose definition of “information.” A meta-definition, perhaps I should say. Let me just quote the opening sentences:

In this paper I forge a naturalistic, or naturalized, concept of information, by relating it to energy dissipative structures. This gives the concept a definable physical and material substrate.

The question “How do you define ‘information’?” is one that gives me the willies. I hear it often in the context of discussing my new book, The Information, which, after all, devotes 500+ pages to the subject. Sometimes I simply refer to the ultimate arbiter, the OED, which, however, requires 9,400 words to answer the question. Kevin Kelly, who put it to me during this interview, had an answer in mind already: Gregory Bateson’s famous phrase, “a difference which makes a difference.” Bateson, in turn, fashioned that clever epigram to encapsulate the mathematical definition created by Claude Shannon, the inventor of information theory. (What Bateson actually wrote was: “A difference which makes a difference is an idea. It is a ‘bit,’ a unit of information.”)

What makes it frustrating for me to define information (and the reason the OED needs to go on so long) is that the word is so important in such different realms, from the scientific to the everyday. These realms are bound at the hip. But the connections aren’t always obvious.

So Salthe tries to tie them up in a package—to make, as he says, a hierarchy of definitions: “The conceptual bases for this exercise will be nothing more than two commonly recognized definitions of information—Shannon’s, and Bateson’s—together with my own, thermodynamic, definition.” The thermodynamic definition, again following Shannon, involves entropy. “My perspective,” says Salthe, “is that the evident distance from thermodynamic equilibrium of our universe is a fact that contextualizes, and subsumes everything else.” (He adds, with air quotes, “Arguing that the ‘real’ definition of information is an amalgam of all three, I find it impossible to say in a single sentence what that definition is.” To which I want to say, welcome to my world.)

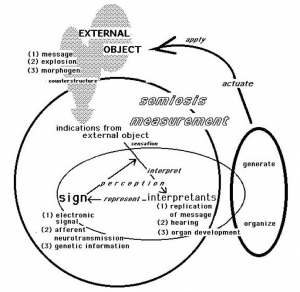

From there, it gets complicated. Very complicated: to give you an idea, here is an illustration. I urge the interested reader to download the full essay. Section 6 has a title that many will consider an understatement: “Interpretation: Information Can Generate Meaning.” That is, after all, why we care. The journey from information to meaning is what matters.

I urge the interested reader to download the full essay. Section 6 has a title that many will consider an understatement: “Interpretation: Information Can Generate Meaning.” That is, after all, why we care. The journey from information to meaning is what matters.

September 8, 2011

Secret No More: Google and Power

Just last month, in an essay for the New York Review, I wrote the following sentence about Google and secrecy:

None of these books can tell you how many search queries Google fields, how much electricity it consumes, how much storage capacity it owns, how many streets it has photographed, how much e-mail it stores; nor can you Google the answers, because Google values its privacy.

As of today, that’s out of date. Google has decided to reveal the answer to two of those questions. James Glanz reports in the New York Times that the company’s data centers worldwide consume just under 260 million watts of electricity and field something over a billion searches a day.

This works out (Google says) to about three-tenths of a watt-hour per search. Google had given out that per-search figure before, in hopes of quieting people who wildly estimated that a single search consumes as much energy as bringing half a kettle of water (however much that is) to boil, or running a 100-watt light bulb for an hour.

Now, 0.3 watt-hours isn’t nothing, but it isn’t much. It sounds worse in joules: about a thousand. You yourself, if you are doing nothing more strenuous than reading this item, dissipate that much energy every twenty seconds or so. Google points out (with considerable justice, in my opinion) that any one search has the potential to save vast amounts of energy—a gasoline-powered trip to the library, for example.

It may feel as though there’s something apples-and-orangish about all this. Energy and information. I hear an echo of something I noted in The Information: that at the dawn of the computer era, in 1949, John von Neumann came up with an estimate for the minimal amount of heat that must be dissipated “per elementary act of information, that is per elementary decision of a two-way alternative and per elementary transmittal of one unit of information.” It was a tiny number; he wrote it as kTln 2 joules per bit.

Oh, and by the way, von Neumann was wrong; Charles H. Bennett and Rolf Landauer have explained why. But energy and information are tightly bound. Of that, at least, there is no doubt.