James Gleick's Blog, page 5

October 31, 2013

March of time, arrow of time, time warp …

This is the kind of thing that’s buzzing through my head as I work on the next book. (It’s an N-gram, computed on the fly by Google here, from the contents of all the books they [in some cases illegally] scanned from libraries.)

(Were you wondering about those “time warp” occurrences in the early 19th century? They come from passages like this (1812): “By keeping up the sluices, and drains, and banks, the land can be refreshed at any time. Warp land has had crops of flax …”)

September 20, 2013

The Zone of Uncertainty (What Pope Francis Said)

Everybody has an opinion or a summary or an interpretation of the interview with Pope Francis, and this is the last place you’d come for more, but one part resonates especially powerfully for me. It’s when he talks about uncertainty and doubt.

In seeking God “in all things,” he says, “there is still an area of uncertainty [una zona di incertezza]. There must be.”

If a person says that he met God with total certainty and is not touched by a margin of uncertainty, then this is not good. For me, this is an important key. If one has the answers to all the questions—that is the proof that God is not with him. It means that he is a false prophet using religion for himself. The great leaders of the people of God, like Moses, have always left room for doubt. You must leave room for the Lord, not for our certainties; we must be humble. Uncertainty is in every true discernment that is open to finding confirmation in spiritual consolation.

For me, this is where religion and science can clasp hands.

August 26, 2013

Why Must an Author Twit?

I’m reading with the greatest pleasure Zoo Time, the latest novel by Howard Jacobson. The narrator is an author called Guy Ableman, and one of its subjects is the parlous state of publishing today.

In this scene, Ableman meets with his publisher, Merton — “a publisher of the old school” who “didn’t know what was what any more.” They have the following all-too-timely conversation:

“Do you know what I am expected to require of you?” he suddenly looked me in the eyes and said. “That you twit.”

“Twit?”

“Twit, tweet, I don’t know.”

“And why are you expected to require it of me?”

“So that you can do our business for us. So that you can connect to your readers, tell them what you’re writing, tell them where you’re going to be speaking, tell them what you’re reading, tell them what you’re fucking eating.”

After that, the conversation naturally turns to “blagging.”

Jacobson, who turned 71 this weekend, does not tweet, as far as I can tell. I do, but at least I can say I’ve never tweeted about anything I was eating.

June 25, 2013

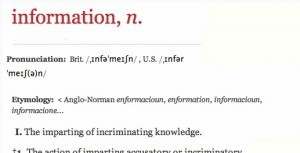

The OED Redefines “Information” Yet Again

The entry for information in the Oxford English Dictionary always makes good reading. It’s substantial: close to 10,000 words long. I see it has changed again.

The last time I looked, the Number One definition was “The imparting of incriminating knowledge.” Excellent! As far as I’m concerned, they could stop right there. Of course, the relevant citations mostly came from early English law texts—Rolls of Parliament from the time of Edward IV, that kind of thing. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England.

As far as I’m concerned, they could stop right there. Of course, the relevant citations mostly came from early English law texts—Rolls of Parliament from the time of Edward IV, that kind of thing. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England.

The objects of the other species of informations, filed by the master of the crown-office upon the complaint or relation of a private subject, are any gross and notorious misdemesnors, riots, batteries, libels, and other immoralities of an atrocious kind.

But no longer. This definition has been quietly demoted. Maybe the lexicographers thought it was too quaint. Now the Number One definition of information is “The imparting of knowledge in general.” I guess it’s hard to argue with that.

Many other important senses remain, of course. There’s the modern, scientific one, due to Claude Shannon (“a mathematically defined quantity divorced from any concept of news or meaning; spec. one which represents the degree of choice exercised in the selection or formation of one particular symbol, message, etc., out of a number of possible ones …”). And the sentimental favorite, the true and venerable meaning of the word, Number III.7: “The giving of form or essential character to something.” As in J. Sharpe, 1630:

The soule or spirit doth giue information, or operation to the whole body, and euery part thereof.

Never mind that it’s “Now rare.“

Does this tinkering have a back story? I’ll try to find out.

April 29, 2013

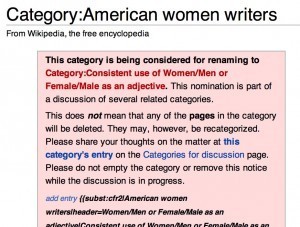

Wikipedia’s Women Problem (2013)

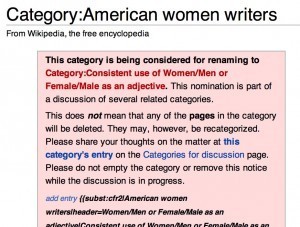

There is consternation at Wikipedia over the discovery that hundreds of novelists who happen to be female were being systematically removed from the category “American novelists” and assigned to the category “American women novelists.” Amanda Filipacchi, whom I will call an American novelist despite her having been born in Paris, set off a furor with an opinion piece on the New York Times website last week. Browsing on Wikipedia, she had suddenly noticed that women were vanishing from “American novelists”—starting, it seemed, in alphabetical order. In the A’s and the B’s, the list was now almost exclusively male:

I did more investigating and found other familiar names that had been switched from the ‘American Novelists’ to the ‘American Women Novelists’ category: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ayn Rand, Ann Beattie, Djuna Barnes, Emily Barton, Jennifer Belle, Aimee Bender, Amy Bloom, Judy Blume, Alice Adams, Louisa May Alcott, V. C. Andrews, Mary Higgins Clark—and, upsetting to me: myself.

The word that came to mind—and the Times used it for the headline—was sexism.

And who could disagree? Joyce Carol Oates expressed her view on Twitter: “Wikipedia bias an accurate reflection of universal bias.  All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

At Wikipedia, all hell broke loose.

(Let’s pause here to flag the phrase, “at Wikipedia.” Wikipedia is a notional place only. It is not situated in a sleek California corporate campus, like Google in Mountain View or Apple in Cupertino, but instead distributed across cyberspace.)

This kind of thing is usually bruited and argued on Wikipedia’s

“Talk” pages. After the Filipacchi article, Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia’s cofounder, created a new entry on his personal Talk page under the bold-face heading, “WTF?” Wales does not give orders or directly cause things to happen. He is more of a

noninterventionist god. He is often referred to simply as Founder (capital F) or Jimbo. Anyway, he wrote:

My first instinct is that surely these stories are wrong in some important way. Can someone update me on where I can read the community

conversation about this? Did it happen? How did it happen?

Heated argument broke out on a page set aside for discussion of changes to Wikipedia categories. Categories are a big deal. They are an important way to group articles; some people use them to navigate or browse.

Categories provide structure for a web of knowledge—not a tree, because a category can have multiple parents, as well as multiple children. Wikipedia lists 4,325 Container catego

ries, from “Accordionists by nationality” to “Zoos in the United States.” There are Disambiguation categories, Eponymous categories—named for example, after railway lines like Norway’s Flåm Line, or after robots (there are two: Optimus Prime and R2-D2)—and at least 11,000 Hidden categories, meant for administration and therefore invisible to readers. A typical hidden category is “Wikipedia:Categories for discussion,” containing thousands of pages of logged discussions about the suitabilities of various categories. Meta enough for you? Some categories under discussion now are Avenues, Omniscience, and “Equestrian commanders of vexillationes.”

It’s fair to say that Wikipedia has spent far more time considering the philosophical ramifications of categorization than Aristotle and Kant ever did.

On Wednesday a formal proposal appeared for discussion: “Propose merging Category:American women novelists to Category:American novelists.” Nominator’s rationale: “As per gender neutrality guidelines, gender-specific categories are not appropriate where gender is not specifically related to the topic. This subcategory also creates the unfortunate side effect that Category:American novelists contains only male novelists.” Many users quickly posted comments agreeing. One user “struck out” two of these votes, on the ground that they appeared to have been submitted by “sock puppets”—new identities created by an existing user for purposes of deception—or at least by people who had created new Wikipedia accounts specifically for the purpose. Yet another user objected to the striking out of the votes:

These are people who have bothered to get involved. By pushing them out of this conversation, you are contributing to the continuing inability for newcomers to feel comfortable here. Especially women. Which is of course, the subject of the article being discussed.

Which, of course, it was. Wikipedia is periodically accused of being a boys’ club. “Around 90 percent of Wikipedia editors are men, and it shows,” New Scientist said earlier this month. Many Wikipedians agree and would like to do something about it. A large majority of commenters voted “Merge.” Some deployed the terms “ghettoization” and “back of the bus.” Then again, a few are voting for ghettoization—or as they say, “Diffuse women but not men,”diffuse being the term for sending members of a parent  category out into a subcategory. At least it’s arguable that “women novelists” is a category of cultural and sociological interest. It was noted that Wikipedia features an extensive article on Women’s Writing in English, as part of Wikiproject Gender Studies and Wikiproject Women’s History.

category out into a subcategory. At least it’s arguable that “women novelists” is a category of cultural and sociological interest. It was noted that Wikipedia features an extensive article on Women’s Writing in English, as part of Wikiproject Gender Studies and Wikiproject Women’s History.

“We should not let the media impose their view of political correctness on Wikipedia,” wrote Petri Krohn, who identifies himself as a Finnish “writer and Internet commentator.” He added—I think with a straight face—“We might also add some generic warning on American people category pages that they mainly contain white males and one should look into the subcategories.”

To ask Jimbo’s question: how did this happen? It turns out that a single editor brought on the crisis: a thirty-two-year-old named John Pack Lambert living in the Detroit suburbs. He’s a seven-year veteran of Wikipedia and something of an obsessive when it comes to categories. He creates a lot of them. Last year he briefly created Category:American people of African-American descent. Then he raised hackles by recreating the defunct category American “actresses,” a word that others felt belongs in the same dustbin as “poetess.”

On April 1 Lambert started working alphabetically through all American novelists and moving the women into Category:American women novelists instead. First he did Patricia Aakhus, at 5:44 PM. Two minutes later, Hailey Abbott. Then Megan Abbott—pausing also to add her to Category:University of Michigan alumni. Then Diana Abu-Jaber, Alice Adams, Lorraine Adams, Renata Adler…. He did English women novelists, too; also Australian, German, and Moroccan. At 8:51, he created a new category, Nigerian women novelists, and put Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie there.

By the end of the day he’d gotten to the D’s: so Daphne du Maurier is now an English woman novelist. Like most people, she falls into multiple categories; she is also a “bisexual writer,” a “British historical novelist,” a “Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire,” an “English person of French descent,” an “English short story writer,” a “writer from London,” and an “LGBT writer from England.” But not (as of this morning) an English novelist.

And so it went. The next day Lambert was briefly sidetracked by a discussion of whether there should be a Category:Jeans enthusiasts (for “celebrities and famous people who are always wearing or frequently spotted wearing jeans”), but then he got back to work and A. L. Kennedy, till then a Scottish novelist, became a Scottish woman novelist. On April 3 he created a category for Greek women screenwriters; so far it has only one member.

And so it went. The next day Lambert was briefly sidetracked by a discussion of whether there should be a Category:Jeans enthusiasts (for “celebrities and famous people who are always wearing or frequently spotted wearing jeans”), but then he got back to work and A. L. Kennedy, till then a Scottish novelist, became a Scottish woman novelist. On April 3 he created a category for Greek women screenwriters; so far it has only one member.

The debate that broke out when Filipacchi’s opinion piece appeared is still running, and the issue appears to be more general and pervasive than most had originally thought. Throughout Wikipedia, in all kinds of categories, women and people of nonwhite ethnicities are assigned only to their subcategories. Maya Angelou is in African-American writers, African-American women poets, and American women poets, but not American poets or American writers. Many editors are saying that people need to be “bubbled up” to their parent categories.

Lambert vehemently disputes suggestions that he is motivated by sexism (or racism, as the case may be). He cites principles of Wikipedia categorization: arguing, for example, that huge categories should be broken up and “diffused” because they become useless for navigation. “This whole hullabaloo is really missing the point,” he told me. “The people who are making a big deal about this are not being up-front about what happens if we do not diffuse categories.” Others argued that laypeople are simply misunderstanding the purpose of a big category like American novelists. “It is really a holding ground for people who have yet to be categorized into a more specific sub-cat,” said a user called Obi-Wan Kenobi. “It’s not some sort of club that you have to be a part of.”

The editor who originally created the American women novelists category—a Londoner named Gareth E. Kegg—voted to merge it with American novelists and said that he had hoped the category would be “an inspiration to young women to know how many others have written before.” He was appalled, he said, “that there are less Wikipedia articles on women poets than pornographic actresses, a depressing statistic.”

A user called lmurchie created a new category: American men novelists. Immediately other Wikipedians objected. A distinctive feature of the Wikipedia culture is the development of shorthand for various rhetorical devices. For example, an editor has only to say, “A new user created this unhelpful WP:POINTy category, compounding our problems,” and everyone knows thatWP:POINT is a link to a page describing a behavioral guideline, titled “Wikipedia:Do not disrupt Wikipedia to illustrate a point.” When one editor argues that it’s unfair to address discrimination only  for the American category, another can retort, “Objection: This is the Slippery Slope Fallacy,” with the relevant hyperlink embedded. It’s all very efficient. You can write (and someone did), “It looks sexist, it sounds sexist WP:QUACK.”

for the American category, another can retort, “Objection: This is the Slippery Slope Fallacy,” with the relevant hyperlink embedded. It’s all very efficient. You can write (and someone did), “It looks sexist, it sounds sexist WP:QUACK.”

For some reason the first two members of Category:American men novelistswere Orson Scott Card and P. D. Cacek, who was also categorized in “American science fiction writers” and “American horror writers.” It took about fifteen hours for someone to realize that Cacek, whose full name is Patricia Diana Joy Anne Cacek, didn’t belong. As of this writing, she is back to being an American novelist and an American woman novelist. Ernest Hemingway is now officially an American man novelist—manly indeed. F. Scott Fitzgerald will be relieved to know that he, too, made the cut.

By the end of the week, swimming against the tide, John Pack Lambert was still removing names from American novelists and adding them not just to American women novelists but to Category:African-American novelists, Category:American historical novelists, Category:American surrealist novelists, Category:19th-century American novelists, Category:American Chicano novelists, some of which he’s creating as he goes. This morning, American Chicano novelists contains only one page, Oscar Zeta Acosta. Acosta also belongs to Hispanic and Latino American novelists, American writers of Mexican descent, American politicians of Mexican descent, Writers from California, People from Modesto, California, and People from El Paso, Texas.

People of Wikipedia! You have a problem.

And Amanda Filipacchi? It seems some Wikipedians need to check the policy on shooting the messenger. The article about Filipacchi is undergoing a flurry of editing, not all well-intentioned. Her categories keep changing. Lambert created a new category, American humor novelists, just so he could move her into it.

~

[Written for the New York Review Blog]

Wikipedia’s Women Problem

There is consternation at Wikipedia over the discovery that hundreds of novelists who happen to be female were being systematically removed from the category “American novelists” and assigned to the category “American women novelists.” Amanda Filipacchi, whom I will call an American novelist despite her having been born in Paris, set off a furor with an opinion pieceon the New York Times website last week. Browsing on Wikipedia, she had suddenly noticed that women were vanishing from “American novelists”—starting, it seemed, in alphabetical order. In the A’s and the B’s, the list was now almost exclusively male:

I did more investigating and found other familiar names that had been switched from the ‘American Novelists’ to the ‘American Women Novelists’ category: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ayn Rand, Ann Beattie, Djuna Barnes, Emily Barton, Jennifer Belle, Aimee Bender, Amy Bloom, Judy Blume, Alice Adams, Louisa May Alcott, V. C. Andrews, Mary Higgins Clark—and, upsetting to me: myself.

The word that came to mind—and the Times used it for the headline—was sexism.

And who could disagree? Joyce Carol Oates expressed her view on Twitter: “Wikipedia bias an accurate reflection of universal bias.  All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

At Wikipedia, all hell broke loose.

(Let’s pause here to flag the phrase, “at Wikipedia.” Wikipedia is a notional place only. It is not situated in a sleek California corporate campus, like Google in Mountain View or Apple in Cupertino, but instead distributed across cyberspace.)

This kind of thing is usually bruited and argued on Wikipedia’s

“Talk” pages. After the Filipacchi article, Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia’s cofounder, created a new entry on his personal Talk page under the bold-face heading, “WTF?” Wales does not give orders or directly cause things to happen. He is more of a

noninterventionist god. He is often referred to simply as Founder (capital F) or Jimbo. Anyway, he wrote:

My first instinct is that surely these stories are wrong in some important way. Can someone update me on where I can read the community

conversation about this? Did it happen? How did it happen?

Heated argument broke out on a page set aside for discussion of changes to Wikipedia categories. Categories are a big deal. They are an important way to group articles; some people use them to navigate or browse.

Categories provide structure for a web of knowledge—not a tree, because a category can have multiple parents, as well as multiple children. Wikipedia lists 4,325 Container catego

ries, from “Accordionists by nationality” to “Zoos in the United States.” There are Disambiguation categories, Eponymous categories—named for example, after railway lines like Norway’s Flåm Line, or after robots (there are two: Optimus Prime and R2-D2)—and at least 11,000 Hidden categories, meant for administration and therefore invisible to readers. A typical hidden category is “Wikipedia:Categories for discussion,” containing thousands of pages of logged discussions about the suitabilities of various categories. Meta enough for you? Some categories under discussion now are Avenues, Omniscience, and “Equestrian commanders of vexillationes.”

It’s fair to say that Wikipedia has spent far more time considering the philosophical ramifications of categorization than Aristotle and Kant ever did.

On Wednesday a formal proposal appeared for discussion: “Propose merging Category:American women novelists to Category:American novelists.” Nominator’s rationale: “As per gender neutrality guidelines, gender-specific categories are not appropriate where gender is not specifically related to the topic. This subcategory also creates the unfortunate side effect that Category:American novelists contains only male novelists.” Many users quickly posted comments agreeing. One user “struck out” two of these votes, on the ground that they appeared to have been submitted by “sock puppets”—new identities created by an existing user for purposes of deception—or at least by people who had created new Wikipedia accounts specifically for the purpose. Yet another user objected to the striking out of the votes:

These are people who have bothered to get involved. By pushing them out of this conversation, you are contributing to the continuing inability for newcomers to feel comfortable here. Especially women. Which is of course, the subject of the article being discussed.

Which, of course, it was. Wikipedia is periodically accused of being a boys’ club. “Around 90 percent of Wikipedia editors are men, and it shows,” New Scientist said earlier this month. Many Wikipedians agree and would like to do something about it. A large majority of commenters voted “Merge.” Some deployed the terms “ghettoization” and “back of the bus.” Then again, a few are voting for ghettoization—or as they say, “Diffuse women but not men,”diffuse being the term for sending members of a parent  category out into a subcategory. At least it’s arguable that “women novelists” is a category of cultural and sociological interest. It was noted that Wikipedia features an extensive article on Women’s Writing in English, as part of Wikiproject Gender Studies and Wikiproject Women’s History.

category out into a subcategory. At least it’s arguable that “women novelists” is a category of cultural and sociological interest. It was noted that Wikipedia features an extensive article on Women’s Writing in English, as part of Wikiproject Gender Studies and Wikiproject Women’s History.

“We should not let the media impose their view of political correctness on Wikipedia,” wrote Petri Krohn, who identifies himself as a Finnish “writer and Internet commentator.” He added—I think with a straight face—“We might also add some generic warning on American people category pages that they mainly contain white males and one should look into the subcategories.”

To ask Jimbo’s question: how did this happen? It turns out that a single editor brought on the crisis: a thirty-two-year-old student of history named John Pack Lambert, enrolled at Wayne State University and living in the Detroit suburbs. He’s a seven-year veteran of Wikipedia and something of an obsessive when it comes to categories. He creates a lot of them. Last year he briefly created Category:American people of African-American descent. Then he raised hackles by recreating the defunct category American “actresses,” a word that others felt belongs in the same dustbin as “poetess.”

On April 1 Lambert started working alphabetically through all American novelists and moving the women into Category:American women novelists instead. First he did Patricia Aakhus, at 5:44 PM. Two minutes later, Hailey Abbott. Then Megan Abbott—pausing also to add her to Category:University of Michigan alumni. Then Diana Abu-Jaber, Alice Adams, Lorraine Adams, Renata Adler…. He did English women novelists, too; also Australian, German, and Moroccan. At 8:51, he created a new category, Nigerian women novelists, and put Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie there.

By the end of the day he’d gotten to the D’s: so Daphne du Maurier is now an English woman novelist. Like most people, she falls into multiple categories; she is also a “bisexual writer,” a “British historical novelist,” a “Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire,” an “English person of French descent,” an “English short story writer,” a “writer from London,” and an “LGBT writer from England.” But not (as of this morning) an English novelist.

And so it went. The next day Lambert was briefly sidetracked by a discussion of whether there should be a Category:Jeans enthusiasts (for “celebrities and famous people who are always wearing or frequently spotted wearing jeans”), but then he got back to work and A. L. Kennedy, till then a Scottish novelist, became a Scottish woman novelist. On April 3 he created a category for Greek women screenwriters; so far it has only one member.

And so it went. The next day Lambert was briefly sidetracked by a discussion of whether there should be a Category:Jeans enthusiasts (for “celebrities and famous people who are always wearing or frequently spotted wearing jeans”), but then he got back to work and A. L. Kennedy, till then a Scottish novelist, became a Scottish woman novelist. On April 3 he created a category for Greek women screenwriters; so far it has only one member.

The debate that broke out when Filipacchi’s opinion piece appeared is still running, and the issue appears to be more general and pervasive than most had originally thought. Throughout Wikipedia, in all kinds of categories, women and people of nonwhite ethnicities are assigned only to their subcategories. Maya Angelou is in African-American writers, African-American women poets, and American women poets, but not American poets or American writers. Many editors are saying that people need to be “bubbled up” to their parent categories.

Lambert vehemently disputes suggestions that he is motivated by sexism (or racism, as the case may be). He cites principles of Wikipedia categorization: arguing, for example, that huge categories should be broken up and “diffused” because they become useless for navigation. “This whole hullabaloo is really missing the point,” he told me. “The people who are making a big deal about this are not being up-front about what happens if we do not diffuse categories.” Others argued that laypeople are simply misunderstanding the purpose of a big category like American novelists. “It is really a holding ground for people who have yet to be categorized into a more specific sub-cat,” said a user called Obi-Wan Kenobi. “It’s not some sort of club that you have to be a part of.”

The editor who originally created the American women novelists category—a Londoner named Gareth E. Kegg—voted to merge it with American novelists and said that he had hoped the category would be “an inspiration to young women to know how many others have written before.” He was appalled, he said, “that there are less Wikipedia articles on women poets than pornographic actresses, a depressing statistic.”

A user called lmurchie created a new category: American men novelists. Immediately other Wikipedians objected. A distinctive feature of the Wikipedia culture is the development of shorthand for various rhetorical devices. For example, an editor has only to say, “A new user created this unhelpful WP:POINTy category, compounding our problems,” and everyone knows thatWP:POINT is a link to a page describing a behavioral guideline, titled “Wikipedia:Do not disrupt Wikipedia to illustrate a point.” When one editor argues that it’s unfair to address discrimination only  for the American category, another can retort, “Objection: This is the Slippery Slope Fallacy,” with the relevant hyperlink embedded. It’s all very efficient. You can write (and someone did), “It looks sexist, it sounds sexist WP:QUACK.”

for the American category, another can retort, “Objection: This is the Slippery Slope Fallacy,” with the relevant hyperlink embedded. It’s all very efficient. You can write (and someone did), “It looks sexist, it sounds sexist WP:QUACK.”

For some reason the first two members of Category:American men novelistswere Orson Scott Card and P. D. Cacek, who was also categorized in “American science fiction writers” and “American horror writers.” It took about fifteen hours for someone to realize that Cacek, whose full name is Patricia Diana Joy Anne Cacek, didn’t belong. As of this writing, she is back to being an American novelist and an American woman novelist. Ernest Hemingway is now officially an American man novelist—manly indeed. F. Scott Fitzgerald will be relieved to know that he, too, made the cut.

By the end of the week, swimming against the tide, John Pack Lambert was still removing names from American novelists and adding them not just to American women novelists but to Category:African-American novelists, Category:American historical novelists, Category:American surrealist novelists, Category:19th-century American novelists, Category:American Chicano novelists, some of which he’s creating as he goes. This morning, American Chicano novelists contains only one page, Oscar Zeta Acosta. Acosta also belongs to Hispanic and Latino American novelists, American writers of Mexican descent, American politicians of Mexican descent, Writers from California, People from Modesto, California, and People from El Paso, Texas.

People of Wikipedia! You have a problem.

And Amanda Filipacchi? It seems some Wikipedians need to check the policy on shooting the messenger. The article about Filipacchi is undergoing a flurry of editing, not all well-intentioned. Her categories keep changing. Lambert created a new category, American humor novelists, just so he could move her into it.

~

[Written for the New York Review Blog]

April 20, 2013

Total Noise Gets Louder

Kids used to ask each other: If a tree falls in a forest and no one hears, does it make a sound? Now there’s a microphone in every tree and a loudspeaker on every branch, not to mention the video cameras, and we’ve entered the condition that David Foster Wallace  called Total Noise: “the tsunami of available fact, context, and perspective.”

called Total Noise: “the tsunami of available fact, context, and perspective.”

This week was a watershed for Total Noise. When terrible things happen, people naturally reach out for information, which used to mean turning on the television. The rewards (and I use the word in its Pavlovian sense) can be visceral and immediate, if you want to see more bombs explode or towers fall, and plenty of us do. But others are learning not to do that.

The Boston bombings, shootings, car chase, and manhunt found the ecosystem of information in a strange and unstable state: Twitter on the rise, cable TV in disarray, Internet vigilantes bleeding into the FBI’s staggeringly complex (and triumphant) crash program of forensic video analysis. If there ever was a dividing line between cyberspace and what we used to call the “real world,” it’s hard to see now.

March 8, 2013

Taking Daylight Saving Time to Extremes

This is the weekend when the clocks do something—spring forward, it must be—and from now on Daylight Saving Time will always remind me of Marcel Aymé, born 111 years ago this month, a writer of “fantastic” stories, not much translated into English.

I stumbled onto Aymé not via Twitter nor word of mouth nor any of the Intertubes but browsing in a bookstore, the kind with tables, on which were displayed neat stacks of books lovingly chosen by the staff. I picked up a collection titled The Man Who Walked through Walls, put out by an independent London publisher, the Pushkin Press. The beautiful translation is by Sophie Lewis.

Aymé is the kind of writer who makes you think of Borges (but that’s too easy, of course; it’s almost worrisome how often I’m put in mind of Borges). “The Man Who Walked through Walls”—”Le passe-muraille“—is his most famous story, the referent for his monument in Montmartre.  The story that made me gasp with pleasure is the fourth in the set, “The Problem of Summertime” (1943). It’s about— well, never mind what it’s “about.” Let’s just say it expresses something about the nature of time that could not have been expressed, could not have been seen, until the invention of Daylight Saving Time (in French, l’heure d’été—literally, summer time), along with time zones and the International Date Line and the other chronometric paraphernalia of modernity. The story is set in wartime. “At the height of the war, the warring powers’ attention was distracted by the problem of summertime, which it seemed had not been comprehensively examined. Already it was felt that no serious work had been carried out in this field and that, as often happens, human genius had allowed itself to be overruled by habit.”

The story that made me gasp with pleasure is the fourth in the set, “The Problem of Summertime” (1943). It’s about— well, never mind what it’s “about.” Let’s just say it expresses something about the nature of time that could not have been expressed, could not have been seen, until the invention of Daylight Saving Time (in French, l’heure d’été—literally, summer time), along with time zones and the International Date Line and the other chronometric paraphernalia of modernity. The story is set in wartime. “At the height of the war, the warring powers’ attention was distracted by the problem of summertime, which it seemed had not been comprehensively examined. Already it was felt that no serious work had been carried out in this field and that, as often happens, human genius had allowed itself to be overruled by habit.”

How easily, the narrator remarks, time can be moved forward an hour or two! (His readers knew well that their German occupiers had just changed France’s time zone by decree.)

On reflection, nothing prevented its being moved forward by twelve or twenty-four hours, or indeed by any multiple of twenty-four. Little by little, the realisation spread that time was under man’s control. In every continent and in every country, the heads of state and their ministers began to consult philosophical treatises. In government meetings there was much talk of relative time, physiological time, subjective time and even compressible time. It became obvious that the notion of time, as our ancestors had transmitted it down the millennia, was in fact absurd claptrap.

So the authorities decide to do something dramatic. Never mind what. Something Borgesian. You could say that time travel occurs, if you construe the term time travel as broadly, as flexibly, as possible.

January 19, 2013

P.S. re preserving our species memory

Having jotted the below item on Twitter and the Library of Congress, I belatedly rediscovered the following. Too easy to forget these things. From the wise and foresighted Steve Martin, 2008:

I have learned that people are uploading their lives into cyberspace and am convinced that one day all human knowledge and memory will exist on a suitable hard drive, which, for preservation, will be flung out of the solar system to orbit a galaxy far, far away.

January 16, 2013

The Twitterverse Goes to the Library

“What food for speculation each person affords, as he writes his hurried epistle, dictated either by fear, or greed, or more powerful love!”

—Andrew Wynter (1854)

For a brief time in the 1850s the telegraph companies of England and the United States thought that they could (and should) preserve every message that passed through their wires. Millions of telegrams—in fireproof safes. Imagine the possibilities for history!

“Fancy some future Macaulay rummaging among such a store, and painting therefrom the salient features of the social and commercial life of England in the nineteenth century,” wrote Andrew Wynter in 1854. (Wynter was what we would now call a popular-science writer; in his day job he practiced medicine, specializing in “lunatics.”) “What might not be gathered some day in the twenty-first century from a record of the correspondence of an entire people?”

Remind you of anything?

Here in the twenty-first century, the Library of Congress is now stockpiling the entire Twitterverse, or Tweetosphere, or whatever we’ll end up calling it—anyway, the corpus of all public tweets. There are a lot. The library embarked on this project in April 2010, when Jack Dorsey’s microblogging service was four years old, and four years of tweeting had produced 21 billion messages. Since then Twitter has grown, as these things do, and 21 billion tweets represents not much more than a month’s worth. As of last month the library had received 170 billion—each one a 140-character capsule garbed in metadata with the who-when-where.

The library has attached itself to the firehose. A stream of information flows from 500 million registered twitterers (counting duplicates, dead people, parodies, imaginary friends, and bots) who thumb their hurried epistles into phones and tablets and PCs, and the tweets pour into Twitter’s servers at a rate of thousands per second—tens of thousands at peak times: World Cup matches, presidential elections, Beyonce’s pregnancy—and make their way in “real time” to a company called Gnip, a social-media data provider in Boulder, Colorado. Gnip organizes them into one-hour batches on a secure server for download, where they are counted and checked and finally copied to reels of magnetic tape, to be stored in a couple of filing cabinets. In different locations, for safety. If you have ever tweeted, rest assured that each of your little gems is there for posterity.

Of course, the chance of even your very best tweet being seen again by human eyes is approximately zero.

This is an ocean of ephemera. A library of Babel. No one is under any illusions about the likely quality—seriousness, veracity, originality, wisdom—of any one tweet. The library will take the bad with the good: the rumors and lies, the prattle, puns, hoots, jeers, bluster, invective, bawdy probes, vile gossip, epigrams, anagrams, quips and jibes, hearsay and tittle-tattle, pleading, chicanery, jabbering, quibbling, block writing and ASCII art, self-promotion and humble-bragging, grandiloquence and stultiloquence. New news every millisecond. A vast confusion of vows, wishes, actions, edicts, petitions, lawsuits, pleas, laws, proclamations, complaints, grievances. Now comical then tragical matters.

Call it what you will, the Twitter corpus now forms a piece of “the creative record of America” and therefore falls squarely within the library’s mission, says Robert Dizard Jr., the Deputy Librarian of Congress. Historians treasure nineteenth-century diaries; why not twenty-first-century tweets? “I think the twitter archive has the potential to allow researchers or scholars to paint a picture of the past with more colors or a fuller brushstroke.”

Scholars and researchers—several hundred of them—have already asked for access, but providing access is not so easy. The tapes are offline. They are organized by date and time. To keep the archive online, indexed for searching, would require server farms with petabytes or more, the sort of thing Google has in legions and the US government not so much.

Google and Twitter can’t seem to get along—they haven’t managed to agree on terms for enabling either real-time or historical searches. Twitter’s own search function is limited and filtered. Only the last few days are available. A Frequently Asked Question in the Twitter Help Center is “I’m Missing from Search!” (How poignant.)

Effectively searching this mass of unstructured data, this barnyard of straw, will be more difficult than people may think. Despite the metadata attached to each tweet, and despite trails of retweets and “favorite” tweets, the Twitter corpus lacks the latticework of hyperlinks that makes Google’s algorithms so potent. Twitter’s famous hashtags—#sandyhook or #fiscalcliff or #girls—are the crudest sort of signposts, not much help for smart searching. Here is a hashtag exegesis in a New Year’s tweet by the comedian Demetri Martin:

The Library of Congress dreams of being able to provide scholars instant results for all kinds of queries—“to be able to answer any question a researcher puts before the archives,” as Dizard says—but that may be a long way off. Right now, to run a single query can take days. The Gnip company, as Twitter’s collaborator, offers a form of historical search for its clients, but it, too, is slow and specialized. “I think there is broad recognition already that there is enormous value that can be derived from the data,” says Gnip’s president, Chris Moody. “That being said, we have to be realistic in terms of what’s going to be available because it is very expensive and it is very challenging.”

At least the job of preservation costs little enough—in the low tens of thousands, the library says. When the early telegrams were saved in safes they had weight and volume—“those sent by the Recording Telegraph being wound in tape-like lengths upon a roller, and appearing exactly like discs of sarcenet ribbon,” as Wynter said. As the telegraph exploded in popularity, there was soon no hope of collecting and storing all that paper. Nowadays, of course, tweets are just bits.

O historian of the future, will you be able to find gems in the straw? Maybe it won’t be worth your while—not unless you have a lot more time than I have. You may sample it, or listen in on something like pure thought, flickering, static-filled, in a vast dark universe.

Still, I’m enjoying my infinitesimal slice, less than one five-millionth of the whole, in real time. I’m hearing new news every day, I’m not believing everything I hear, and I’m certainly not tracking statistics or spotting trends. Mostly I believe that Twitter is a mirage—— but wait, let’s hear from a neophyte: