Roy Miller's Blog, page 265

February 23, 2017

When Writing a Biography Becomes a Race Against Death

Of all the conversations I had while writing my most recent book, I remember one particular exchange distinctly. The man I was speaking with told me that his friend had died just days before, and the news, oddly, caused us both to laugh.

It was, of course, the laughter of irony. The man knew I was a writer, and found some dark humor in the fact that his friend had lived more than 80 healthy years, but had chosen to die only a few days before I learned of his existence.

I was laughing to cover my disappointment not only that the man’s friend died, but had taken with him on his trip to the grave a stockpile of memories that I had been hoping would shed some light on the subject of my book.

I have found this to be a peculiar element of the task of researching the kind of history that has almost, but not quite, receded completely into the history books. Documents, artifacts, letters—these are sources of information that, if preserved, can be available to historians and writers forever. But memories have a limited lifespan—limited by the lives of their possessors.

Article continues after advertisement

Though I consider my work important, as most writers do, this part of the process has an undeniably ghoulish quality to it.

Having written two literary biographies, I’ve spent a lot of time hunting for memories. Finding the right source—somebody who knew my subject five, six, seven decades ago—can open doors in research that have been heretofore closed and locked. Find the right person, and he or she can be the key to new insights and fresh paths for a narrative. Only death stands in the way.

Though I consider my work important, as most writers do, this part of the process has an undeniably ghoulish quality to it. Many times I’ve discovered the name of a person who might aid my research, typed it into a search engine, and been rewarded with an obituary. In most cases, the actual mourning for the death has been over for years. For me, it’s just beginning. Because in this type of hunt, finding out that your target is alive is only the first step. A number of other criteria also must be met for the operation to be a success.

The living, breathing source must be healthy of mind and spirit—at least healthy and clear-minded enough to recall those distant memories that could add detail to the story. And they must be the type of person capable of sharing those recollections, of determining what it is that they’ve experienced that could be of value to a narrative. On many occasions, I’ve found a source who knew my subject intimately, but, no matter how I phrased my questions, always responded with some version of “He was a great guy.”

The source, once found, must also be willing to share the valuable information he’s been holding for all these years. Some just don’t want to talk. Maybe they hate your subject and don’t want him or her to be remembered. Or maybe they just hate writers.

Clues found along the way are often harbingers of success or failure. The phrase “nursing home” can be a bad sign. The inhabitants of such facilities, for obvious reasons, often don’t make for the best interviewees. The search must continue, however, because if there’s no death certificate, there’s still a chance.

While working on my most recent book, I spent weeks calling ex-Marines whose names were listed on faded military records, searching for somebody who had served with my subject in the 1950s. Most were dead or untraceable. Finally, I located one of them living in an old-age facility. His caretaker said he was “on the machine,” unable to speak, and instructed me to call at a specific time a few days later.

At the agreed upon time I called, expecting, at best, a faint voice from a dying old man. To my surprise, I was greeted with the sharp sound of Marine authority. My spirits soared.

“I’ve got a few minutes for you,” he barked. “Who are you writing about?”

I told him the name.

“Never heard of him.”

Once the disappointment fades, though, it’s on to the next. I discovered on another occasion that an important source was living in a nursing home in Southern California. I called repeatedly, only to be told by staff members at the facility that he was very sick, and in no condition to speak on the phone for an interview. I lived across the country and was not in a position to travel without any assurance that an interview would actually take place.

The morbid quality of this work can be somewhat negated when, as a writer, you get the feeling you are preserving something significant that otherwise would fade into oblivion.

In desperation, I wrote him a letter explaining my project and asking for his participation. Time passed, and I soon forgot about the letter. One day, months later, the phone rang. It was my Southern California source, miraculously feeling better and ready to answer my questions. We spoke for hours, and he offered me anecdote after anecdote, all filled with the kind of specific details that I needed to write convincingly about life in America 60 years in the past.

The morbid quality of this work can be somewhat negated when, as a writer, you get the feeling you are preserving something significant that otherwise would fade into oblivion. My first book was about the legendary Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray. Murray had a group of lifelong friends who called themselves The Geezers. For decades, these men, all noted sports writers themselves, traveled together annually to cover all the great American sporting events—the Super Bowl, the Masters, the Kentucky Derby.

Murray was the first to die among them. When I began my research into his life, I wrote out a list of the Geezers, oldest to youngest, and began interviewing them, one by one. Each shared insightful stories about Murray and about what it was like to be a sports journalist in the second half of the 20th century. In the years since the publication of the biography, I’ve read the obituaries of many of these men, with great sadness for their passing, but also with the pride of knowing that I had been able to save some little part of their life experience for posterity.

In the search for memories, the best possible outcome is that the person you find is not only alive and willing to talk, but someone who truly understands the game and his or her role in it, and appreciates the firm deadline imposed by the beckoning grave. That’s why the perfect source is usually another writer.

My most recent book is about the author Harry Crews. When I went to his house to a few years back, he was in very poor health, in a wheel chair, and in need of round-the-clock care. The end, we both knew, was near. But his mind was sharp.

I made my request. Would he be willing to be interviewed, dig deep into his memory bank, and answer question after question about his most personal experiences?

“Sure, bud, you can ask me anything you want,” he said, looking up with a twinkle in his eye. “But you’d better do it quick.”

The post When Writing a Biography Becomes a Race Against Death appeared first on Art of Conversation.

February 22, 2017

PEN America Announces 2017 Literary Award Winners

PEN America has announced the winners of the majority of its 2017 Literary Awards, which include novelist, essayist, and critic Aleksandar Hemon for his oral history of Bosnian migrants, How Did You Get Here?: Tales of Displacement, and novelist Helen Oyeyemi for her debut story collection, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours.

"As global and national political discourse turn toward exclusion, PEN America continues to uphold the humanities' place in fostering coherent dialogue," PEN America president Andrew Solomon said in a statement. "Many of this year's honored books explore the social themes that are at the surface of our nation's consciousness. The PEN America Literary Awards grant us a critical opportunity to recognize the literary excellence of these works and to celebrate the varied experiences of their creators."

Winners of the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award, the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature, the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction, and the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay will be announced live at the 2017 PEN America Literary Awards Ceremony. The ceremony, to be hosted by comedian Aasif Mandvi, will be held on March 27 at The New School's John L. Tishman Auditorium in Manhattan.

The 2017 awards will confer 23 distinct awards, fellowships, grants, and prizes, totaling to nearly $315,000. PEN America established its Literary Awards program in 1963.

The post PEN America Announces 2017 Literary Award Winners appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Wednesday Poetry Prompts: 385 | WritersDigest.com

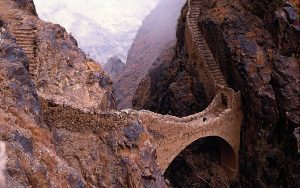

For today’s prompt, write an ekphrastic poem. That is a poem based on a piece of visual art–a painting, a photograph, a sculpture. Your choice. If you have something in mind already, go with it. If not, here are a few images to get you started.

*****

Revision doesn’t have to be a chore–something that should be done after the excitement of composing the first draft. Rather, it’s an extension of the creation process!

In the 48-minute tutorial video Re-creating Poetry: How to Revise Poems, poets will be inspired with several ways to re-create their poems with the help of seven revision filters that they can turn to again and again.

*****

Here’s my attempt at an Ekphrastic poem:

“A Girl”

He fell for a girl

when he was still young

but couldn’t say the words

so he grabbed a gun

and received a mask,

a spear, and a horse

dreaming of that girl

who married, of course,

another fellow

who lived like a dove

as the hawks fought hard

for their secret loves.

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is Senior Content Editor of the Writer’s Digest Writing Community and author of Solving the World’s Problems (Press 53). And he loves ekphrastic poems.

Follow him on Twitter @RobertLeeBrewer.

*****

Find more poetic posts here:

You might also like:

CATEGORIES

Poetry Prompts, Robert Lee Brewer's Poetic Asides Blog, What's New

About Robert Lee Brewer

Senior Content Editor, Writer's Digest Community.

The post Wednesday Poetry Prompts: 385 | WritersDigest.com appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Review: In Joan Juliet Buck’s Memoir, a Parade of Stars and Styles

As a young girl, she knew only that “Peter Autoul,” as she thought of him, was an Irishman with brown, curly hair and a slightly crooked nose who had something to do with her father’s business and might be a big success some day. That was before Autoul — actually Peter O’Toole, who had formed a production company with Buck’s father — appeared in his first conspicuous movie and agreed to the hair color and nose changes that would land him the role of T. E. Lawrence in a big desert spectacle. “Lawrence of Arabia” was the only O’Toole movie that Jules Buck did not produce between 1959 and 1975, the glory years of the actor’s career.

Photo

Credit

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

When O’Toole squired Joan to the premiere of “Lord Jim,” he gave her enduring advice for how, at least, to look like him in the spotlight: “Shut your mouth and look surprised.” But he “gave no clue as to how to raise the inner edges of his eyebrows to create the expression of amused disdain that made him look like a prince,” Buck remembers now.

During her teens, as she tells it, Buck became a romantic magnet for talent. In London, at 17, she met a writer who was just beginning to become very well known. “What is the most important thing in the world?” she asked him. “Status,” he said, “and added that he’d marry me if I wrote a book.” She didn’t write a book, and he didn’t marry her, but she says she gave him one of the phrases for which he remains best known. The phrase is “starved to near-perfection,” and the man was Tom Wolfe.

Continue reading the main story

Think of anyone who had cachet in the worlds of movies, literature or fashion, starting in 1970 or so, and chances are good that they pop up in this book, even if all Buck ever did was consider the person’s proposition and turn it down. Go to the Greek Island of Hydra with Leonard Cohen after meeting him only casually? She thought his skin might be wrinkly, so made apparently weak excuses. He sent her flowers with a note that read, “Never lie to a great poet, or even a minor one.”

Despite their globe-trotting and anything but parallel careers, Buck and Huston seemed to maintain a competition, mostly at Buck’s instigation. She acknowledges being envious of Huston’s acclaimed acting career and movie star boyfriend (Jack Nicholson).

Buck, who did a lot of interviews with stars, went to the set of “1900” and wound up falling hard for Donald Sutherland.

But however well Buck knew free-range celebrities, she wasn’t truly intimate with the way the fashion world worked until she became part of it. The book describes her naïve shock at seeing erstwhile friends in the business start behaving like advertisers; trying to be politically and culturally neutral in her wardrobe choices (not easy at all); and deciding what kinds of values Vogue ought to endorse. Less interesting: thoughts about whether or not her apartment was haunted, notes on office politics and even this quick, witty summary of a runway show: “Lights, music, girls, no plot.”

It would take a more heavily illustrated book to weigh the pros and cons of Buck’s most daring moves, like using quantum physics as the theme for an entire issue of Vogue. Did her editorial choices have anything to do with her removal? Or was it simply, as she says, some confusion about the vials of seawater she carried everywhere, which catty co-workers mistook for syringes?

All of this pales in comparison with the catastrophe that derailed her freelance career: accepting an assignment from Anna Wintour’s American Vogue in 2011 to go to Syria and interview Asma al-Assad, the wife of the Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad. “It was a terrible idea, but I didn’t call Anna to ask her what she was thinking,” Buck writes. Soon after the article ran, Assad’s forces began attacking civilians, and Buck became a pariah in the magazine world.

There are many things in “The Price of Illusion” that don’t sound candidly complete. But Buck has been a fabulous Zelig in the world of memoirs. She has witnessed or experienced a book’s worth of tellable tales, tall or otherwise. She’s certainly entitled to a version of her own.

Continue reading the main story

The post Review: In Joan Juliet Buck’s Memoir, a Parade of Stars and Styles appeared first on Art of Conversation.

16 Things All Historical Fiction Writers Need to Know

When I was in the second grade, we had two units. Remember units? The first semester we read books about animals. And the second semester, we read books about the “Olden Days”. In June, the teacher asked everyone to raise their hands as to which unit they liked better. I was the only one who voted for “Olden Days.” I was a historical fiction fan from the get-go.

As a literary agent who has represented many successful historical fiction authors and books, I think it’s important all writers who want to break into this great category consider these key elements when writing and marketing their work. Here’s what you need to know about this very particular yet wide open area:

This guest post is by Irene Goodman. Goodman has been agenting for 37 years, and after a slew of #1 bestsellers and successful authors, it just never gets old. She loves to find new authors and help them to create careers.

Originally from the Midwest, she learned early to talk straight and stand up straight. There are seven agents in her agency, The Irene Goodman Agency (all women). They are known for their joyful approach, fierce commitment to excellence and killer shoes.

Follow her and her agency’s stable of agents on Twitter @IGLAbooks.

1. Historical fiction can be anywhere from the dawn of time up to about 1950-60

Any later than that and it hasn’t yet acquired that special patina. We want it real, but without feeling like we’re reading the news.

2. This kind of fiction requires high quality writing

It’s not like genre writing and it’s not something you can just dash off. It requires education, thought, and skill.

3. No matter how clever you think it is, it must have a hook

A general story about a real person’s life may not be enough. Which would you rather read: 1) a story about General Sherman’s march to the sea, or 2) General Sherman skips the town of Augusta, GA on his march to the sea, because he promised his southern girlfriend that he would leave her home town intact?

[5 Writing Tips to Creating a Page Turner]

4. You can write about anything that really happened

You can’t write about things that you know didn’t happen. But the catch is that you can write about things that could have happened. No one will ever know what General Sherman said to his girlfriend in private, but maybe he said “wait for me”. He could have, right? You can go with that.

5. Time travel can work

Yes, time travel is historical fiction, if more of the story takes place in the past than in the present. You can also do split stories, with some in the present and some in the past.

6. The more famous, the better

It’s far better, if you choose to write about someone who really lived or any iconic personality, to go with a marquee name. Which would you rather read: 1) the real story behind Helen of Troy, or 2) the real story of Menelaus? (If you’re saying “Who?, then you get my point.)

7. Promoting minor characters

However, you can take a minor character from literature and tell the story from that person’s point of view, providing a fresh take on an iconic subject. Example: THE RED TENT, which provides an eye-opening take on a little-know character in the bible. It works because it’s the bible, which is kinda famous, and because it also features Jacob, Rachel, Leah, and Joseph. And it doesn’t hurt that it’s a little sexy. Not a lot, but enough to dispel any lofty perception of the bible as preachy.

[How To Write Novels When You’re A Parent]

8. Strong women needed

In the last several years, historical fiction has focused mainly on women. That is starting to change. You still need that hook, though.

9. Western Europe is the safest place to set a story.

American settings were not popular for a long time. I’m not sure why, but American history didn’t seem very sexy. Now American stories are starting to come back into the light. It’s about time!

10. What’s out? The Tudors. All of them

Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth I—the whole gang. They were mined incessantly during the last decade or so. If that’s what you want to write about, think about doing something else unless you have something very new and different to offer about the Tudors.

11. What’s in? WWII is very in at the moment, but it’s starting to saturate

Wholly fictional stories are becoming prominent, as opposed to novelized biographies. Strong women are very in. No doormats. This can be a problem, as women weren’t often in a position where they could take a lot of action, but you can show their spirit and also show the constraints.

12. 17th Century big names

What would I love to see? Something in the 17th century. I know, sounds vague, right? But what if I said Cyrano de Bergerac? That helps, doesn’t it? I would also love to see something to do with Harriet Tubman. She has been one of my heroes since I first learned of her when my daughter was in the 4th grade and schools suddenly discovered her. Now she is going to be on the twenty dollar bill. (Harriet, not my daughter).

13. Research, research, research

You knew I was going to bring up research, didn’t you? You were right. Historical fiction requires more than a Wikipedia check. It means going to the places where they lived and worked. It means going to real brick and mortar libraries or museums in order to find that one out of print British book or that obscure Italian recording.

[5 Important Tips on How to Pitch a Literary Agent In Person]

14. Weave historical details in seemlessly

Don’t let anyone say “Your research is showing!”

15. Always check the comp titles

Let’s back up a little. Before you do any of these things, find out if your subject has been done before. Spend some time online looking at comparable titles, or comp titles, in publishing speak. You may very well find something similar, but that’s not a bad thing. They want to know there’s a market for it, but you must present in a way that gives it a fresh look.

16. Start organizing early.

Have a web site. Get on social media. Do anything you can as early as you can to promote yourself and start building an audience. Oh, and don’t forget the most important element of writing historical fiction: Have fun!

Want to have the first draft of your novel finished one month from today?

Use this discounted bundle of nine great resources to make that happen.

Order now.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

Brian A. Klems is the editor of this blog, online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

Listen to Brian on: The Writer’s Market Podcast

You might also like:

The post 16 Things All Historical Fiction Writers Need to Know appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Schoenhof’s books, a Harvard Square landmark, will live online only

It’s the final chapter for the iconic Schoenhof’s Foreign Books in Harvard Square.

After 161 years of serving academics, students, writers, and customers from every corner of the world, Schoenhof’s said Wednesday that it will close its doors next month. It will operate as an online store.

Read the complete story at BostonGlobe.com.

Don’t have a Globe subscription? Boston.com readers get a 2-week free trial.

Close

Catch up with The Boston Globe for free.

Get The Globe's free newsletter, Today's Headlines, every morning.

Thanks for signing up!

Boston Globe Media Privacy Policy

The post Schoenhof’s books, a Harvard Square landmark, will live online only appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Thomas Lux, Poet Who Wrote of Life’s Absurdities, Dies at 70

Thomas Lux, in a photograph from 1993.

Credit

Lynn Saville

Thomas Lux, a poet who used spare, direct language to express the absurdities and sorrows of human life, and whose 1994 collection, “Split Horizon,” won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, one of the most lucrative prizes in American poetry, died on Feb. 5 at his home in Atlanta. He was 70.

The cause was lung cancer, said his wife, Jennifer Holley Lux.

Mr. Lux showed a rare gift for blending comedy and disturbing surrealist images in his early collections “Memory’s Handgrenade” (1972), “The Glassblower’s Breath” (1976) and “Sunday: Poems” (1979). A character in the poem “Five Men I Knew” dreams he is reading “Duino Elegies” by Rilke “aloud, / in German, at a racetrack in Florida,” when suddenly “the flamingos are drained of their color / and collapse.”

His early manner, according to the reference work Contemporary Poets, was “tormented and tortured, full of complex and disjointed images reflecting an insane and inhospitable world.”

With time, Mr. Lux gravitated toward a taut, precise realism, finding his subject matter in seemingly mundane events to which he applied an often comic twist, reflected in titles like “Attila the Hun Meets Pope Leo I” and “Like Tiny Baby Jesus, in Velour Pants, Sliding Down Your Throat (a Belgian Euphemism).”

In “Refrigerator, 1957,” the depressing contents of a midcentury icebox — “boiled potato in a bag, a chicken carcass under foil” — give way to a wondrous jar of maraschino cherries, “heart red, sexual red, wet neon red, / shining red in their liquid.” In “Motel Seedy” he expressed the soul-destroying décor of a cheap hotel room:

To put this color

green — exhausted grave grass — to cinder blocks

takes an understanding of loneliness

and/or institutions that terrifies.

In a 1999 interview with The Cortland Review, Mr. Lux said: “Making poems rhythmical and musical and believable as human speech and as distilled and tight as possible is very important to me. I started looking outside of myself a lot more for subjects.”

His work was gathered in more than a dozen collections. Two compilation volumes were published in the mid-1990s — “The Blind Swimmer: Selected Early Poems, 1970-1975” and “New and Selected Poems: 1975-1995.”

Thomas Norman Lux was born on Dec. 10, 1946, in Northampton, Mass., where he grew up on a dairy farm run by his grandfather and uncle. His father, Norman, delivered milk for the farm. His mother, the former Elinor Healey, answered telephones at a local Sears store.

He studied English literature and took poetry workshops at Emerson College in Boston, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1970. In his senior year, James Randall, one of his teachers, published his poems in “The Land Sighted,” a chapbook. He pursued graduate studies at the University of Iowa but returned after a year to teach at Emerson, where he was named poet in residence.

While teaching at Emerson he married Jean Kilbourne. The marriage ended in divorce, as did a second marriage. Besides his wife, he is survived by a daughter from his first marriage, Claudia Lux.

Continue reading the main story

With “Half-Promised Land,” published in 1986, Mr. Lux began turning away from surrealism. Many of the poems in that collection drew on childhood memories of the family farm. At the same time, he retained the wild comic sense that made for such memorable subjects as “Commercial Leech Farming Today” and “Walt Whitman’s Brain Dropped on Laboratory Floor.”

“Usually, the speaker of my poems is a little agitated, a little smartass, a little angry, satirical, despairing,” he told the arts journal Cerise Press in 2009. “Or sometimes he’s goofy, somewhat elegiac, full of praise and gratitude.” He added: “I think one uses humor/satire to help combat the darkness. I do.”

In 1975 Mr. Lux began teaching at Sarah Lawrence College. At the same time, he served on the faculty of the M.F.A. program for writers at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, N.C. In 2002 he became the Bourne professor of poetry and director of the McEver Visiting Writers Program at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

Mr. Lux’s poetry collections also included “The Drowned River” (1990), “The Street of Clocks” (2001), “The Cradle Place” (2004) and “Child Made of Sand: Poems, 2007-2011” (2012).

His most recent collection, “To the Left of Time,” was published last year. Just before his death, he finished editing “I Am Flying Into Myself,” a selection of poems by Bill Knott, a poet who greatly influenced his early work. It was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on Feb. 14.

Continue reading the main story

The post Thomas Lux, Poet Who Wrote of Life’s Absurdities, Dies at 70 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

8 Highly Unusual Writing Residencies

This year, the Mall of America turns 25—and in order to celebrate itself (I suppose), the monument to American consumerist enterprise is holding a contest for a Writer-in-Residence, who will “spend five days deeply immersed in the Mall atmosphere while writing on-the-fly impressions in their own words,” as well as doubling as a tourist attraction, sitting at their desk for at least four hours a day, with their work “displayed in almost-real time on a large monitor at the workspace.” Work that the Mall will then own, of course. Honestly? This is so weird that someone should actually do it. After all, just because they’ll own whatever you write during the five days you’re trapped there, doesn’t mean the experience won’t turn into a dope novel later. But in case you don’t want to write at a desk in front of tourists, here are a few other highly unusual, but definitely less frightening writers’ residencies to consider applying for (or at least, in the case of bygone programs, pine over).

Fremont Bridge Residency

In 2016, the city of Seattle invited poets and essayists to apply to write in the Fremont Bridge. Yes, in the bridge—or more precisely, in a studio in the bridge’s northwest control tower. I think it’s clear that the hardest thing about this residency would be resisting all the obvious metaphors.

Article continues after advertisement

[image error]

Jan Michalski Foundation Residency

Need clean lines and a futuristic mindset in order to finish your literary project? Now you can live in one of seven hyper-modern treehouses, each designed by a different international architecture firm, overlooking Lake Geneva and the Alps. There’s also an eighth treehouse that serves as kitchen and common area. Residents can stay for two weeks or up to six months, depending on their project, and the foundation pays 1,200 Swiss Francs a month, which is about what I’d guess it would normally cost a night to stay in a place like this.

[image error]

Speaking of treehouses, here’s one that looks a bit more like what you put together in the woods behind your house—although still a lot better. Outlandia is a completely off-grid workspace, up a mountain in Glen Nevis, Lochaber, Scotland, open to creatives of all types—though they are seeking residents with “experimental, radical approaches to a challenging natural and working environment” and “proposals that engage with the tensions around nature, industry, tourism and heritage.”

[image error]

Voices of the Wilderness Residency

Lots of National Parks have writing residencies, but this Alaskan wilderness retreat is a little different. Instead of just being sequestered in a cabin in the woods, “residents are paired with a wilderness ranger, with whom they explore the national forests, parks, or refuges, while assisting with research, fieldwork, and other light ranger duties.” In case you’re a writer who has always secretly wanted to be a park ranger in the wildest, weirdest state.

[image error]

Hawthornden Castle

If your dream is to lock yourself away in a distant castle and write that novel about a girl locked away in a distant castle, writing that novel about, ahem, okay, anyway, this is the residency for you. But honestly, the strangest thing about it isn’t that you get to live in a 17th-century Scottish castle once inhabited by the poet William Drummond—it’s that you can’t apply, or even get information about applying, online. You have to send away for a packet. How charming. Also charming, of course, is the silence, the solitude, and, as Pauls Toutonghi put it, “the lasting magic of William Drummond, the thing worth celebrating. The poet’s sanctuary—the physical embodiment of the poetry, itself—turned out to be as much a part of his life’s work as anything else. His legacy was manifold. Though time could ‘close the thousand mouths of fame,’ the castle would endure—unbreachable even by celebrity—its pale pink limestone walls standing as sanctuary above the meandering currents of the Esk.” Oh and by the way, here’s another residency in a castle—this one’s in Poland.

[image error]

Andrews Forest Writers Residency

If your writing has a strong relationship to the natural world, you might consider immersing yourself in an ancient forest for a couple of weeks. As part of Oregon State’s Long-Term Ecological Reflections program, which seeks to create a two-hundred year record (2003-2203) of humanity’s interactions and experiences with the forest, writers can live at the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon, wander the woods, interact with the scientists, and, of course, write.

[image error]

Amtrak Residency

Famously, the Amtrak Residency was born when Alexander Chee tweeted that he wished there was one. Though it got a medium amount of flak over the fine print, the residency was still a good idea—writing on the train for hundreds of miles! Romance is not dead! Scenery, etc. Delicious, delicious train food. Anyway, the residency has been put on hold for the moment. Maybe someone should tweet at them?

[image error]Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"jdm-credit-cara-sucher-vertical","orientation":"0"}" data-image-title="jdm-credit-cara-sucher-vertical" data-image-description="" data-medium-file="http://16411-presscdn-0-65.pagely.net..." data-large-file="http://16411-presscdn-0-65.pagely.net..." class="aligncenter wp-image-60455" src="https://i1.wp.com/16411-presscdn-0-65..." srcset="https://i1.wp.com/16411-presscdn-0-65... 3265w, http://16411-presscdn-0-65.pagely.net... 300w, http://16411-presscdn-0-65.pagely.net... 768w, http://16411-presscdn-0-65.pagely.net... 1240w" sizes="(max-width: 600px) 100vw, 600px" data-recalc-dims="1"/>

Antarctic Artists & Writers Program

You know what’s unusual? Antarctica. The National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program sends writers and artists to the frozen tundra—a place few people ever have access to. The program is “specifically designed to increase the public’s understanding and appreciation of the Antarctic and human endeavors on the southernmost continent.” I think this would either be deeply inspiring or drive you completely mad.

The post 8 Highly Unusual Writing Residencies appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Fiction: In the Japanese Hit ‘Six Four,’ a Police Inspector Weighs Questions of Loyalty.

In Hideo Yokoyama’s “Six Four,” a Japanese policeman searches for two lost teenagers, one of them his own daughter.

Source link

The post Fiction: In the Japanese Hit ‘Six Four,’ a Police Inspector Weighs Questions of Loyalty. appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Writers, Veterans, Citizens Take to the Halls of Congress

A common chant at the protests over the last month goes like this: Tell me what democracy looks like! The answer, of course, is: This is what democracy looks like.

When I went to Washington to protest the Muslim ban, I was also there to find out what democracy looked like.

I was with a group of writer-veterans and American Muslims. I was part of their community because I wrote a book about a veteran, and because there are few groups I’d rather protest with. Vets are informed and forceful. In today’s noisy arguments, veterans’ voices have an unassailable authority. And the Muslims would speak from personal experience, reporting from the battleground of religious interaction.

Our first meeting is at the State Department. There are 15 of us, and we sit at a long table with a senior staffer. We go around the circle. I explain that I’m the President of the Authors Guild, and that we see the Muslim ban as a free speech issue. We believe that denying entry to thousands of journalists, authors, professors and translators sends a chilling message regarding that most fundamental of our democratic rights, and to do so on religious grounds adds a second layer of discrimination.

Article continues after advertisement

The man next to me is Rasool, an Iranian. He’s in his forties, soft-spoken and well-dressed. He’s getting his PhD here, he’s an imam in a local mosque, and he also teaches at a private Muslim school. “I speak at Friday prayers to my congregation,” he says. “I’ve always told them that the lines are blurred, in this country, between the religions. That hands are stretched across these lines in friendship.” He pauses. “I can’t say that now. And at the school, I’ve always told the children that America was the highest example of religious tolerance in the world. I can’t say that now.” He takes out his cell phone. “Let me read you a quote, from the leader of Iraq.” He reads. “’I want to thank the new US president for doing in two weeks what we have spent the last ten years trying to do.’” He looks up. “He means, to drive a wedge between the two countries.”

The staffer nods. “Thank you.”

Andrew, our organizer, served four tours in Iraq and now teaches at American University. He says, “We’re hearing from our friends in the field that this is having catastrophic consequences. It has hurt all our friends and allies. Counterterrorism is a thinking man’s game. This is a blunt instrument.”

Jerri is in her fifties, retired from Navy Intelligence. She worked in Moscow. “In counterterrorism,” she says, “the work is based entirely on trust. The relationships take years to develop. The reason people cooperate with us is that they have a more appealing view of our country than they do of theirs.” She pauses. “They won’t have that view now. Now they see that we’ll turn on our allies. This ban has badly damaged our national security.”

The staffer nods.

Colin was a tank commander in Iraq, and now teaches college English. He says, “This is a moral issue for me. I was fighting there because I believed in our values, and the people who helped us believed in them too. Our interpreter believed in us. His son was kidnaped and tortured because he worked for us. I still believe in our values, and this ban is a violation of trust. What does it say to our interpreter, who lost his son?”

The staffer says, “Sometimes we receive directives that we have to adjust to,” he says. “I can tell you that we agree about the knock-on consequences of this.”

We go on around the table.

Matt, who was an Army captain in Iraq, says that the new president of Somalia is a professor from New York. Isn’t this the kind of relationship we want, inviting people here to study under a free system, so that they can go back to the Muslim world and teach others what they have learned from our democracy? Instead of blocking them, and sending a message of hate and fear? And besides, he says that he’s been told we already have the most stringent vetting procedure in the world.

The staffer sighs. They hear us, he says. There is a deep abiding anxiety about terrorism in this country, and it connects to skin color, clothes, ethnic identity. We all have citizen obligations to form bonds throughout our communities and reduce the anxiety.

We leave feeling heartened. I like his candor, and I like the phrase “citizen obligation,” which makes me feel as though we really are all in this together. So I like this vision of democracy.

Senator Markey is a Democrat from Massachusetts. We sit around the table while his aide listens to us.

Hussein is from Somalia. He’s a former Marine who served in Ramadi; now he works in counterterrorism in Somalia. He has told the Somalians that Americans do not hate Muslims. But Somalians believe only the leader of the country. “Now,” he says, “if I try to say this I’ll be laughed out of the room. I can’t imagine how I could respond. It has has done severe damage to what I do.”

Rasool says thousands of refugees are trying to flee Daesh. Americans don’t need to be protected from the refugees. How is this a matter of national security? The aide says, “You have identified the biggest mistake in the president’s reasoning: confusing victims of war with the perpetrators of it. And we have the most stringent system of vetting in the world.”

The aide is brisk and courteous. “Thank you for coming in,” he says. “The Senator agrees with everything you’ve said.”

At Senator Joe Manchin’s office, from West Virginia, we sit in the conference room and the aide takes notes. Matt, the former Army captain, says that we’re a nation of immigrants, whether we came in the 19th century because of the potato famine, like his family, or last year, because of civil war, like some of the people in this room. He says that this ban contradicts the most fundamental precepts of America.

Remaz is a young Muslim woman whose family came from Sudan. She is tall and graceful, in pants, high boots and an elegantly wrapped blue hijab. She has lived here since the age of six. “America is my country. I have no other.” She majored in conflict resolution, and she’s studying for her L-SATS. She also runs a youth group for young girls. After the election, she says, the girls were in tears, afraid of what might happen to them. “I told them not to be scared,” Remaz said, “but I understood why they were. A man tried to run me over in his truck because of my headscarf. When I dodged out of the way he rolled down the window and yelled, ‘You’re not in Iraq now, bitch!’”

The room is silent.

The aides says, “I’m so sorry.”

Another Muslim woman says that West Virginia has a disproportionate number of Muslims in the health care system. If all the Muslim green cards were revoked, she says, the hospital would close.

The aide laughs. “I’ve heard that,” she says. “Thank you for coming in. Senator Manchin is one of the most liberal Democrats in the caucus, and he’ll meet soon with the president, and I hope this will be part of the conversation.”

So far we like what democracy looks like. But we’ve been talking to Democrats.

Our last visit is to Senator Marco Rubio’s office. We are told to wait in the hall. A man with greying hair comes up and asks if we are vets or something. We say we are, and he leads us down the hall. We think we’re heading for a conference room, but he walks to the stairwell. Here he stops and faces us, backed by three flags and two aides, clean-cut young men with clipboards. We form a ragged circle facing him. A school group floods down the hall toward us, laughing and talking.

The staffer tells us that he’s Director of Outreach. “At least I think that’s my title. Is it?” he grins at an aide, who nods. “Why don’t you go around the circle and tell me what you’d like to say.”

The acoustics are terrible in the big open stairwell, opening onto the marble corridor. The elevator is beside us, and people move through us constantly, talking. Our voices are blurred, our circle disrupted. As we talk the staffer stands before each speaker, turning his back to everyone else. He disagrees with us. When we speak against the ban he corrects us.

When Jerri explains the damaging message it sends to our allies in other countries, the staffer asks, “Don’t you think that damage was already done by the previous administration?” Jerri doesn’t answer, because it clearly wasn’t.

Colin, the tank commander, says we have created waves of refugees in these countries, and now we have a responsibility to take them in.

The staffer disagrees. Apparently Hillary Clinton is to blame. “That list was made by Clinton and Barack Obama. You have to look back before the last two weeks to see when the damage was actually done.”

I don’t know what list he’s talking about, and I can’t really hear because his back is to me. The acoustics are so bad I’m not sure if he said “List” or something else, and the constant interruptions make it impossible to have a discussion. Even Remaz is rattled, and speaks quickly and impersonally. The staffer goes around the circle, disagreeing with anyone who criticizes the ban.

Then he stands in front of the flags, flanked by his aides.

“I understand that everyone here is hurting to a certain degree,” he says. “All I can do is make sure that the Senator hears what you’ve said.”

“Can you give us an idea of his response to this policy?” someone asks.

“Not yet, but he’s a thoughtful guy. We look forward to hearing it.”

The staffer looks genially around and we look silently back: the Army captain who’s heard catastrophic reports from the field, the woman in Navy Intelligence, the imam who can’t answer his congregation, the Somali who can’t answer his friends. The tank commander who feels betrayed. Remaz, who nearly died because of her blue hijab. The staffer nods as though we’re all set. He looks at me and grins.

“Did you get everything down?” he asks.

“I hope so,” I say, scribbling.

He starts back down the hall, aides following with their clipboards. We are silent.

And this is also what democracy looks like.

The post Writers, Veterans, Citizens Take to the Halls of Congress appeared first on Art of Conversation.