Roy Miller's Blog, page 269

February 18, 2017

This Week’s Bestsellers: February 20, 2017

Royal Family

The #3 book in the country is King’s Cage, third in a projected four-book YA fantasy series by Victoria Aveyard. The first two installments, 2015’s Red Queen and 2016’s Glass Sword, have sold a combined 394K copies in ; the trade paper edition of Red Queen is at #20 in Children’s Frontlist Fiction, up two positions from the week before. Also up: first-week print unit sales of each book in the series.

First-Seek Print Unit Sales for the Red Queen Series

(See all of this week's bestselling books.)

Page to Screen

As media tie-in editions of two books—Hidden Figures and A Dog’s Purpose—hold the #5 and #10 spots in the country overall, two new tie-ins debut on our lists.

In Before I Fall by Lauren Oliver, #11 in Children’s Frontlist Fiction, a popular teen lives the last day of her life seven times, Groundhog Day style. Conventional editions of the novel, which originally pubbed in 2010, have sold 131K copies in hardcover, 249K copies in trade paper. The movie opens March 3.

Big Little Lies, based on Liane Moriarty’s 2014 novel, is #24 in Mass Market. The HBO series debuted February 19 and stars Nicole Kidman, Reese Witherspoon, and Shailene Woodley. The trade paper tie-in missed that list by just a couple of spots, but the 2015 conventional trade paperback outsold them both. Taking the three editions together, the title sold 14K print copies in the week.

Back for More

Swedish author Fredrik Backman sells respectably in hardcover, but he’s become a mainstay on our lists since the 2015 trade paper publication of his first novel, A Man Called Ove. He’s since published two more novels, the most recent of which just made its trade paper debut.

Week ended Feb. 12

New & Notable

Neil Gaiman

#1 Hardcover Fiction, #1 overall

In this retelling of the tales of Odin, Thor, Loki, and others, “Gaiman has great fun in bringing these gods down to a human level,” our review said.

John Darnielle

#8 Hardcover Fiction

Our starred review called musician Darnielle’s second novel “a slow-burn mystery/thriller whose characters are drawn together by an eerie discovery.”

Min Jin Lee

#22 Hardcover Fiction

Lee mines the immigrant experience in what our review called “an exquisite meditation on the generational nature of truly forging a home.”

Listen to PW Radio’s interview with Lee.

Top 10 Overall

Rank

Title

Author

Imprint

Units

1

Norse Mythology

Neil Gaiman

Norton

42,914

2

Echoes in Death

J.D. Robb

St. Martin’s

34,450

3

King’s Cage

Victoria Aveyard

HarperTeen

23,551

4

1984

George Orwell

Signet Classics

22,133

5

Hidden Figures (movie tie-in)

Margot Lee Shetterly

Morrow

20,806

6

A Man Called Ove

Fredrik Backman

Washington Square

19,953

7

Love from the Very Hungry Caterpillar

Eric Carle

Grosset & Dunlap

19,206

8

Hillbilly Elegy

J.D. Vance

Harper

17,710

9

The Cellulite Myth

Ashley Black

Post Hill

17,295

10

A Dog’s Purpose (movie tie-in)

W. Bruce Cameron

Forge

16,607

All unit sales per Nielsen BookScan except where noted.

A version of this article appeared in the 02/20/2017 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: PW Bestsellers

The post This Week’s Bestsellers: February 20, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Week of February 20, 2017

Knopf Nabs a Biography of Anne Spoerry

Sonny Mehta and Andrew Miller of Knopf secured world rights to In Full Flight: A Story of Africa and Atonement, a biography of Anne Spoerry by John Hemingway, in a deal brokered by Jacques de Spoelberch of J de S Associates. According to the agent, the book tells the story of how Spoerry, known as the Flying Doctor, “saved hundreds of thousands of East Africans until her death in 1999.” The book also goes into Spoerry’s “work as a WWII resistance fighter [and] her capture by the Germans and subsequent imprisonment in the horrific women’s concentration camp Ravensbruck.” Knopf plans to publish In Full Flight in spring 2018.

Debut Author Brings a Noir Sci-Fi Trilogy to Kensington

In a deal arranged by Laurie McLean of Fuse Literary Agency, Kensington’s Liz May purchased print, digital, and audio world English rights to a noir science fiction trilogy by debut author Nick Taylor. According to McLean, Kensington will begin publishing the series—which features the titles Sinthetic, Sindicate, and Sindrome—in January 2018, to kick off the launch of the publisher’s new Rebel Base Books imprint. According to McLean, Sinthetic is a “cross between Blade Runner and I, Robot” that centers on a detective named Jason Campbell who “investigates a string of murders of synthetic women and uncovers a vast conspiracy.”

Sourcebooks Takes Three Books in Thriller Series

Sourcebooks’ Mary Altman acquired world rights (excluding audio) to a new romantic thriller series by Juno Rushdan. The three-book deal was negotiated by Sara Megibow of KT Literary. According to Megibow, the series centers on Maddox Kinkade, a “fixer for a clandestine government agency, known as the Gray Box, tasked with preventing the sale of a deadly bioweapon.” Kinkade’s partner in the mission turns out to be a former lover who she’d assumed was dead—“by her own hand.” Sourcebooks plans to publish the first title in the series, A Long Way to Fall, in summer 2018; both sequels will follow later in 2018.

Waxman Brings Novel of Carpool Drama to Berkley

Berkley executive editor Kate Seaver took North American rights to A Variety of Tremendous Things, the second novel by Abbi Waxman, in a deal brokered by Alexandra Machinist of ICM Partners. According to the publisher, the novel is loosely related to the author’s debut novel, The Garden of Small Beginnings, which Berkley will publish this May, and which has already sold in 13 countries. A Variety of Tremendous Things, said the publisher, “follows a group of families whose main daily connection is that they carpool their children to school together,” and whose relationships become strained by the revelation of an affair. Berkley plans to publish the book as a trade paperback original sometime in 2018.

Europa Picks Up Debut Noir Novel Set in Glasgow

Michael Reynolds, editor-in-chief at Europa, acquired U.S. rights to Bloody January, a debut noir novel by Alan Parks, in a two-book deal negotiated by Andrea Joyce, rights director of Canongate, on behalf of the author and Tom Witcomb of Blake Friedman in the U.K. According to Europa, the novel takes place in the 1970s in Glasgow, “a city that is rife with drug trafficking and organized crime,” and centers on Harry McCoy, a detective. Europa plans to release the novel in March 2018 “as a key title in the press’s major relaunch of its crime list.” Canongate will publish the book in the U.K. in early 2018.

A version of this article appeared in the 02/20/2017 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: Deals

The post Week of February 20, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

“Depressed clowns, dancing bears, lunatic nuns and smitten mobsters”

“If you were to go to sleep and dream of life in early 20th Century Montreal, Heather O’Neill’s The Lonely Hearts Hotel is what you might dream. The Giller-shortlisted author’s new novel has all the absurd, frightening, fantastical qualities of a midnight reverie — complete with depressed clowns, dancing bears, lunatic nuns and smitten mobsters — and with a similar power to haunt … When their much-anticipated reunion takes place, it does nothing to disrupt the bittersweet mood of the book. Great joy and immense sadness follow as their story unfolds, and the two set about staging the circus they’d envisioned as children. It would be hard to overstate here just how the good the writing is in The Lonely Hearts Hotel. For it is stunningly, stunningly good … O’Neill, always an original and enchanting storyteller, is at the height of her powers. The Lonely Hearts Hotel is a feat of imagination, accomplished through the tiny, marvellous details she scatters across the page.”

–Tara Henley, The Toronto Star, February 12, 2017

Read more of Tara’s reviews here

Article continues after advertisement

The post “Depressed clowns, dancing bears, lunatic nuns and smitten mobsters” appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Hunched Over a Microscope, He Sketched the Secrets of How the Brain Works

Illustrations by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the Spanish neuroscientist, from the book “The Beautiful Brain.” From left: A diagram suggesting how the eyes might transmit a unified picture of the world to the brain; a purkinje neuron from the human cerebellum; and a diagram showing the flow of information through the hippocampus in the brain.

Some microscopes today are so powerful that they can create a picture of the gap between brain cells, which is thousands of times smaller than the width of a human hair. They can even reveal the tiny sacs carrying even tinier nuggets of information to cross over that gap to form memories. And in colorful snapshots made possible by a giant magnet, we can see the activity of 100 billion brain cells talking.

Decades before these technologies existed, a man hunched over a microscope in Spain at the turn of the 20th century was making prescient hypotheses about how the brain works. At the time, William James was still developing psychology as a science and Sir Charles Scott Sherrington was defining our integrated nervous system.

Meet Santiago Ramón y Cajal, an artist, photographer, doctor, bodybuilder, scientist, chess player and publisher. He was also the father of modern neuroscience.

Image

A self-portrait of Ramón y Cajal in his laboratory in Valencia, Spain, about 1885.

“He’s one of these guys who was really every bit as influential as Pasteur and Darwin in the 19th century,” said Larry Swanson, a neurobiologist at the University of Southern California who contributed a biographical section to the new book “The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal.” “He’s harder to explain to the general public, which is probably why he’s not as famous.”

Last month, the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis opened a traveling exhibit that is the first dedicated solely to Ramón y Cajal’s work. It will make stops in Minneapolis; Vancouver, British Columbia; New York; Cambridge, Mass.; and Chapel Hill, N.C., through April 2019.

Ramón y Cajal started out with an interest in the visual arts and photography — he even invented a method for making color photos. But his father pushed him into medical school. Without his artistic background, his work might not have had as much impact, Dr. Swanson said.

“It’s fairly rare for a scientist to be a really good artist at the same time, and to illustrate all of their own work, brilliantly,” Dr. Swanson said. “There seems to be a real resurgence of interest between the interaction between science and art, and I think Cajal will be an icon in that field.”

The images in “The Beautiful Brain” illustrate what Ramón y Cajal helped discover about the brain and the nervous system, and why his research had such impact in the field of neuroscience.

Ramón y Cajal wanted to know something no one really understood: How did a neural impulse travel through the brain? But he had to lean on his own observations and reasoning to answer this question.

Image

Pyramidal cells stained with the Golgi method by Ramón y Cajal.

Ramón y Cajal’s life changed in Madrid in 1887, when another Spanish scientist showed him the Golgi stain, a chemical reaction that colored random brain cells. This method, developed by the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi, made it possible to see the details of a whole neuron without the interference of its neighbors. Ramón y Cajal refined the Golgi stain, and with the details gleaned from even crisper images, revolutionized neuroscience.

In 1906 he and Golgi shared a Nobel Prize. And in the time in between, he wrote his neuron doctrine — the theory of how individual brain cells send and receive information, which became the basis of modern neuroscience.

Image

Ramón y Cajal's illustrations of two contrasting theories of the brain’s composition: the reticular theory, left, and the neuron doctrine that he proposed.

Ramón y Cajal’s theory described how information flowed through the brain. Neurons were individual units that talked to one another directionally, sending information from long appendages called axons to branchlike dendrites, over the gaps between them.

He couldn’t see these gaps in his microscope, but he called them synapses, and said that if we think, learn and form memories in the brain then that itty-bitty space was most likely the location where we do it. This challenged the belief at the time that information diffused in all directions over a meshwork of neurons.

The theory’s acceptance was made possible by Ramón y Cajal’s refinement of the Golgi stain and his persistence in sharing his ideas with others. In 1889, Ramón y Cajal took his slides to a scientific meeting in Germany. “He sets up a microscope and slide, and pulls over the big scientists of the day, and said, ‘Look here, look what I can see,’” said Janet Dubinsky, a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota. “‘Now do you believe that what I’m saying about neurons being individual cells is true?’”

Albert von Kölliker, an influential German scientist, was amazed and began translating Ramón y Cajal’s work, which was mainly in Spanish, into German. From there the neuron doctrine spread, replacing the prevailing reticular theory. But Ramón y Cajal died before anyone proved it.

Image

Perhaps one of Ramón y Cajal’s most iconic images is this pyramidal neuron in the cerebral cortex, the outside part of the brain that processes our senses, commands motor activity and helps us perform higher brain functions like making decisions. Some of these neurons are so large that you don’t need a microscope to see them, unlike most other brain cells.

Image

Ramón y Cajal studied Purkinje neurons with fervor, illustrating their treelike structure in great detail, like this one from the cerebellum. Axons, such as the one indicated by an “a” in the picture, can travel long distances in the body, some from the spinal cord all the way down to your little toe, said Dr. Dubinsky, who wrote a chapter in “The Beautiful Brain” about contemporary extensions of his work. Ramón y Cajal traced axons as far as he could, she said.

Image

A few of his drawings had features that resembled the work of other artists. In some, Vincent van Gogh appeared influential. In this drawing of the glial cells in the cerebral cortex of a man who suffered from paralysis, the three nuclei (or nucleoli) in the upper left corner resemble Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.”

Image

In addition to showing how information flowed through the brain, Ramón y Cajal showed how it moved through the whole body, allowing humans to do things like vomit and cough. When we vomit, a signal is sent from the irritated stomach to the vagus nerve in the brain and then to the spinal cord, which excites neurons that make us contract our stomach and heave. Similarly, a tickle in the back of your throat can make you cough: The larynx sends a signal to the vagus nerve, then the brainstem and the spinal cord, where neurons signal the muscles in our chest and abdomen to contract. Ahem.

Image

CreditD. Berger, N. Kasthuri and J.W. Lichtman

This image is a reconstruction of a dendrite (red) and its axons (multicolored) in the outer part of a mouse’s brain. The dendrite has little knobby spines that stick out and receive chemical messages passed from another neuron’s axon across the synapse, or gap between them, via the tiny white sacs called vesicles. Today we know that synapses are plastic, meaning they can get stronger or weaker with use or neglect. This enables us to think and learn.

This is what Ramón y Cajal described in his neuron doctrine.

“People regularly begin seminars with pictures of the drawings that Cajal made because what they’ve added fits right in with where Cajal thought it should be,” Dr. Dubinsky said. “What he did is still relevant today.”

________

Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.

The post Hunched Over a Microscope, He Sketched the Secrets of How the Brain Works appeared first on Art of Conversation.

February 17, 2017

Poetry Needs a Revolution That Goes Beyond Style

America is an experiment.

Thomas Jefferson thought that there needed to be a rebellion against the existing government every 20 years, even if, as he recognized, some of those rebellions were fueled more by ignorance than a desire for liberty. During this election year, we may well ask if all rebellions are equally valued, but every generation certainly needs a revolution of the word. The initial rebellions of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, the Black Arts Movement, and Hip Hop are already two generations behind us. Since that time, American poetry’s mainstreams have absorbed some of the stylistic manners of these movements but not the burning desire for unpredictability, development, and change. What the mainstreams have absorbed is some of the technique but not the motivation. A style that was cutting edge 20 years ago isn’t going to cut it now. A style that is cutting edge right now won’t be so for long.

Art isn’t easy. It’s not just that we need a revolution in style but also a revolution in audience, distribution, circulation, performance, perception and, indeed, motivation. These revolutions are never a question of being marked as ahead of the times—that is the problem with the label avant-garde, with its flamboyant promise of “being out front.” Rather, the issue is staying in and with the times and not letting the times drown you.

All the standard terms for inventiveness in the arts are vexing, even when well-intentioned. Experiment can suggest that the focus is on work-product or test results despite the fact that writing that is open to new possibilities is more likely to be aesthetically accomplished than work that closes off such possibilities. Avant-garde often evokes a hermetically-sealed tradition hobbled by its own triumphalism. We need avant-garde literary history to revolutionize overly narrow lineages and to acknowledge that the revolution of the word was fomented by writers who operated both inside and outside the cultural, ethnic, religious, or racial mainstreams. Which is to say, along with a host of literary scholars, artists and anthologists from the past few decades, that avant-garde history has not always acknowledged its innovators. At the same time, many of those hostile to what they call avant-garde poetry gerrymander the term to suit their foregone biases against it.

Article continues after advertisement

Rather than saying avant-garde, we say en garde: wake up, poetry is about to begin!

It’s not just that we need a revolution in style but also a revolution in audience, distribution, circulation, performance, perception and, indeed, motivation.

In 2015, as for 100 years before, innovative poetry continued to be controversial. Of course, there is much to be critical of in poetry’s multitude of iterations and most practitioners of anything remotely resembling the experimental are quick to make a wide range of criticism, since this is a group of unlike-minded individuals. But all the hoopla suggests that what’s innovative is, paradoxically, at the vital center of contemporary poetics and that its symbolic constructions are therefore subject to the most virulent scrutiny and worthwhile critique.

But, yes, the innovative needs to change, to revolve, or else it will become nothing more than the fashion and design wing of officially sanctioned verse culture. Or you could say all the en-garde is is an indication of change.

The exploration of identities has always been at the center of radical and exploratory poetry. Indeed, you can define a difference between official verse culture and its opposites as one between work that assumes a fixed identity and work that forges new identity constructions. In this sense, identity is a space for exploration, invention, re-creation, and experimentation. No one group has, or has ever had, a monopoly on this. The source of the most provocative American poetics is the collective linguistic expression of all groups refracted into culturally specific works.

In the brutal calculus of official verse culture, it is claimed that identity is erased in “experimental” writing. But one person’s erasure may be another’s path to freedom, just as one person’s experimental diversion may be another’s fate. We favor thick description over thin convention: the discovered over the assumed. Identity is a process and an intersection: it something that unfolds as it is veiled. We are not against writing from one’s identity; rather, we seek a more robust engagement with identity than is often found in conventional writing or narrowly defined experimental writing collections. We wanted to open up Best American Experimental Writing 2016 to a range of voices that, we hope, enrich each other by being in the same volume.

We edited the book in collaboration with the two series editors. We were asked to make 45 selections from work either published in 2015 or not yet published. We further created our own, stricter, criteria to bring more voices into this conversation: No current or recent students or colleagues at institutions where we have primarily worked. No authors who were published in the first two BAX anthologies (that meant leaving out much work that we admire). We also excluded anyone whose poetic work was published by the early 1990s. Since so many poets from this generation are continuing to do some of the best experimental work around, we felt we needed to make room here for new writers (or anyway, newer ones). But we didn’t want to leave out the older generations entirely, so we have included select works by major figures working outside genres for which they are known. We also didn’t select any translations, as we felt including just a few would fall woefully short of representing the vibrancy of poetry written around the world. We’d like to a see a book like this one just of translations, emphasizing also new approaches to the art. In addition to our 45 selections, the series editors made 15 selections. The remainder of the works in the anthology were selected from submitted manuscripts; these were picked by the series editors and us. We hope that this mix makes for a strong volume and contributes to the development of the BAX series. Although we are happy with the resulting volume, the necessary compromises among the four editors, and the inevitable space limitations, has meant that we were disappointed we could not include many outstanding works. We especially want to express our appreciation to the many extraordinary poets who submitted work we were unable to include as well as our colleagues, students and friends. We could not do what we do without our intersecting and ever-expanding communities.

Editors of anthologies committed to the best of conventional writing are likely to reject work because they have never seen anything like it before. In contrast, we tend to reject work that strikes as having been done before—unless the “done before” was done over. It’s not that great work isn’t written in forms that have been previously established: much of the greatest poetry has been written this way. But there is a still a place for something else and indeed a need for something else. That’s where we come in.

In surveying the field in 2015, we found multiple, contrasting trends including work that was multilectical, multiethnic and multilingual; site-specific; constraint-based; work engaged with visual design and layout; poetry in programmable media; work that uses web data mining; appropriation via transcription, reframing, and resisting; ecopoetics; various approaches to radical transliteration, geography, affirmation and remediation, and performance writing.

Poetry is connected to the origins of language and possibilities for language, the poetics beyond what the eye sees or ear hears.

We also wanted to include work that fell outside the usual borders of innovative poetry. We have included work of a few visual artists, including graphic artists, who work with words. And we have included transcriptions of a few writing-based songs, works whose lyrics stand up on their own as poetry. That is, we have brought together writers that aren’t usually in the same room because they come from a wide variety of social and cultural positions. Being in the same room—this collection—makes possible one, of many, necessary conversations.

Poetry is connected to the origins of language and possibilities for language, the poetics beyond what the eye sees or ear hears: what makes logic and language possible. Poïesis is soul-making and builds worlds. All the voices in this room have been given room, because the source of poetry and poetics isn’t the shadow of any one language, group, or culture. Poetry, the kind of poetry we want, is language that breaks its ties to assumed performances of understanding and assumed relationships.

In the U.S. mainstream, 2015 saw the expansion of legal civil rights for same-sex partners and more cognizance of Trans presence in American life, increasing awareness of the historic, sustained blight of police violence, particularly against Black lives. 2015 also saw declining incomes for most Americans, widespread poverty, unconscionable rates of incarceration (especially for people of color), widespread and widely noted racist and gendered aggression, the cementing of an extremist and undemocratic financial disparity between the super rich and the rest of us. And yet, there’s has also been the simultaneous atomization, intersectionality and interconnectivity of individuals, groups and, the planet.

Without a reversal of the maldistirbution of wealth and power, including cultural agency, no real social progress is possible.

But great poems are still being written.

From the introduction to Best American Experimental Writing 2016. Used with permission of Wesleyan University Press. Copyright © 2016 by Charles Bernstein and Tracie Morris.

The post Poetry Needs a Revolution That Goes Beyond Style appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Karen Berger to Launch Berger Books Imprint at Dark Horse

Karen Berger, former executive editor of DC Entertainment’s influential Vertigo imprint and a pioneering graphic novel publisher, is teaming with Dark Horse Comics to launch Berger Books, a new line of creator-owned comics and graphic novels.

Berger will acquire, edit and oversee the comics and graphic novels published by Berger Books. She will oversee the Berger Books imprint from her home in New York City.

All Berger Books will be branded with both the Berger Books and Dark Horse Comics logos. The number of titles, authors and creative teams will be named at a later date. Berger Books, like all Dark Horse books, will be distributed to the book trade by Penguin Random House Publisher Services.

The announcement of the launch of Berger’s new Dark Horse imprint was made today, February 17, at ComicsPro, the comics shop industry retailers association, at their annual meeting in Memphis, Tenn., where Berger was also awarded the organization’s Industry Appreciation Award.

Dark Horse president and publisher Mike Richard described Berger as “a visionary thinker and one of the most highly regarded individuals in the comic book industry.”

“Her fiercely independent streak and forward-looking storytelling instincts are a perfect match for Dark Horse Comics. We’ll have more news in the near future, but today we’re thrilled to announce that Karen Berger and Berger Books have found the perfect home at Dark Horse Comics,” Richardson said.

Berger started at Vertigo in 1993 and stepped down after 20 years leading the imprint and after more than 30 years at DC Entertainment. During her time at Vertigo, Berger published comics work by many of the most highly acclaimed creators of nonsuperhero genre comics in North American publishing.

Under her direction Vertigo became known for publishing a wide variety of critically acclaimed genre and literary works by a host of now-prominent British writers and artists. Artists that she published include Alan Moore (Swamp Thing) and Grant Morrison (The Invisibles), as well as popular Americans like Brian Azzarello (100 Bullets), Brian K. Vaughan (Y the Last Man) and Scott Snyder (American Vampire).

Indeed, she is credited with ushering in the world of graphic novel publishing that characterizes the American comics marketplace today, a market that now offers a growing body of readers a wider variety of comics material far beyond just superheroes.

Since stepping down at DC in 2012, Berger has kept a relatively low profile, surfacing here and there with some freelance editorial projects. Indeed she was on hand at the recent New York Comic Con to talk about several upcoming projects.

Berger said that “Dark Horse has been at the frontline of independent, creator-owned comics for decades. It’s great to be working with a company that has such a rich history of publishing. I’m very fired up about being back in the game in a big way, and to be producing this new line with top, diverse creative talent and exciting, original new voices.”

The post Karen Berger to Launch Berger Books Imprint at Dark Horse appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Manuscript Rejection Feedback: 3 Critiques to Heed (and 2 to Ignore)

One agent loves your setting, but feels your characters fall flat. An editor likes your premise but can’t connect with your voice. If your head has begun to spin from the manuscript rejection feedback you’re receiving while on submission, you’re not alone.

The trick is to figure out which criticism is worth considering. Once I determined how to separate wheat from chaff, I did some of my best revising while my debut novel (Fräulein M., Tyrus Books/Simon & Schuster) was on submission. My rejections ranged from one-liners (“Not for me, thanks”) to lengthy revise-and-resubmit notes and even a few phone calls with editors. The secret, I found, was to pay closer attention to matters of craft than taste. Here are a few specific examples of each:

This guest post is by Caroline Woods. Woods is the author of Fräulein M., available everywhere books are sold from Tyrus Books (Simon & Schuster). She has taught creative writing to undergraduates at The Boston Conservatory and Boston University, where she earned her MFA. Her work has appeared in Slice Magazine, LEMON, 236, and The Scene. You can learn more about Caroline at carolinewoodswriter.com. Follow her on Twitter @carocour and here on Facebook.

This guest post is by Caroline Woods. Woods is the author of Fräulein M., available everywhere books are sold from Tyrus Books (Simon & Schuster). She has taught creative writing to undergraduates at The Boston Conservatory and Boston University, where she earned her MFA. Her work has appeared in Slice Magazine, LEMON, 236, and The Scene. You can learn more about Caroline at carolinewoodswriter.com. Follow her on Twitter @carocour and here on Facebook.

1. “Your subplot detracts from your main storyline.”

Verdict: Revise.

My agent and I heard this comment from several acquisitions editors. What held us back at first was that both my agent and I loved the subplot, which was about a pregnant teenager in Vietnam War-era America. We were both attached to her and her struggle. But editors found it too distracting from my principal story about women in the Weimar Republic. Eventually, I decided the subplot was cannibalizing the book. I did a major overhaul, shrinking it from approximately one-third of the story to a small frame. This decision finally led to a book deal. As a consolation, my agent and I decided I could rewrite my pregnant teen character into a future book.

[When Do I Spell Out Numbers?]

2. “The structure of your novel is confusing.”

Verdict: Revise.

A lovely agent I queried early in the process pointed out that my multiple-POV novel did not have a predictable structure. She suggested that I reorganize it into chapters of relatively even length and alternate between POV characters in a consistent pattern. I followed her advice, even though it took a lot of work—I even converted several first-person chapters into third so that the book flowed more smoothly. If it is important to you to create a varied, unpredictable mosaic of a book, then by all means ignore this sort of advice. But having a loosely constructed novel did nothing to strengthen my story, so this was feedback I gladly accepted.

3. “This (or that) character isn’t likeable.”

Verdict: Ignore.

I heard this a lot. The problem was that I almost never heard it about the same character. Acquisitions editors had differing opinions about which of the two orphan sisters at the heart of Fräulein M. was more likable—or if they were likable at all. Berni’s transgender best friend, Anita, sparked even wilder swings of opinion. Agents and editors either adored her or hated her. I was tempted at times to change her character, but in the end I’m glad I didn’t. I don’t believe characters have to be likable (just believable). Keeping Anita moody and jealous allowed me to contrast her with a Nazi character who at first appears charming and kind. And in the end, the Booklist review of Fräulein M. claimed Anita “steals the show as the novel’s most compelling character,” further proving how subjective character likability can be.

4. “Your monster isn’t enough of a monster.”

Verdict: Revise.

Only one editor mentioned this, but I took it seriously. The oil that drives your novel-machine is conflict. The main source of conflict in my novel was simply not behaving badly enough to justify the lifelong rift he causes in a sister relationship. Furthermore, I’d chosen a heavy and important topic—World War II and the Holocaust. I realized I had to adequately explore the evils committed in that time period. By intensifying one character’s actions, I could increase both the narrative tension and historical significance of my work.

[Here Are 7 Reasons Writing a Novel Makes You a Badass]

5. “I didn’t connect with the voice.”

Verdict: Ignore.

The first few times I read these words, I panicked. The voice?! What was the matter with my voice? I’d stare at the opening sentences of my book with only the vaguest idea of what “voice” even is or how I could fix it. The bottom line is that your voice is your voice. It changes at a glacial pace, as you age and experience and read. When I see these words in a rejection letter in the future, I will recognize them for what they are: a kinder way of saying, “I just don’t like this book.” And that’s okay. When you see that someone doesn’t like your voice, take a breath and move on. There will be better advice in another letter.

With this combination of tutorials, books, and webinars, you’ll learn everything from what editors are looking for in pitches to how to format your manuscript for submission:

With this combination of tutorials, books, and webinars, you’ll learn everything from what editors are looking for in pitches to how to format your manuscript for submission:

— Formatting & Submitting Your Manuscript

— The Writer’s Digest Guide To Query Letters

— The Weekend Book Proposal: How to Write a Winning Proposal in 48 Hours and Sell Your Book

— How to Make Your Submission Stand Out

—And more!

Click here to order this heavily discounted bundle now.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

Brian A. Klems is the editor of this blog, online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

Listen to Brian on: The Writer’s Market Podcast

You might also like:

The post Manuscript Rejection Feedback: 3 Critiques to Heed (and 2 to Ignore) appeared first on Art of Conversation.

17 Great Books About American Presidents for Presidents’ Day Weekend

LINCOLN: “Lincoln,” by David Herbert Donald

There are so many books published about Lincoln every year — probably more books in total than on any other president — that prizes exist solely to honor books about our 16th president. Yet this (fairly massive) 1995 biography by David Herbert Donald, a Harvard historian, pulls together much of the scholarship into a definitive single volume that views Lincoln’s failings and fumbling as much as his achievements. Donald succeeds in demythologizing and humanizing one of the most admired public figures in American history.

Photo

GRANT: “Personal Memoirs,” by Ulysses S. Grant

There are several great biographies of Grant, including one coming from Ron Chernow this fall, but it’s quite possible that no one wrote about our 18th president and former commanding general of the United States Army better than Grant himself. Considered to be one of the gold standards of military memoirs, Grant’s book was an instant best seller, hailed by both critics and the public for its honesty and high literary quality, and has remained in print and on college curriculums ever since. Grant finished the book several days before he died in 1885.

McKINLEY: “The Triumph of William McKinley: Why the Election of 1896 Still Matters,” by Karl Rove

Surprised to know that George W. Bush’s former senior adviser is also an amateur historian? Some might be even more surprised to know that the book is quite good, with widely positive reviews from critics when it came out in 2015. Rove was long obsessed with McKinley’s election and with the repercussions that particular political moment has had since, down to the unexpected victory of Donald Trump. According to our reviewer, Rove’s “richly detailed, moment-by-moment account in ‘The Triumph of William McKinley’ brings to life the drama of an electoral contest whose outcome seemed uncertain to the candidate and his handlers until the end.”

THEODORE ROOSEVELT: “The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt,” by Edmund Morris

It was this Pulitzer Prize-winning book that inspired Ronald Reagan to request the author, Edmund Morris, to be his official biographer. (The result of that endeavor, “Dutch,” didn’t go entirely according to plan.) The first of a three-part biography of Teddy Roosevelt (the other two volumes, “Theodore Rex” and “Colonel Roosevelt,” were equally acclaimed), this book is considered one of the best biographies of the 20th century. Our reviewer described it as “magnificent,” calling it “a sweeping narrative of the outward man and a shrewd examination of his character,” a rare work “that is both definitive for the period it covers and fascinating to read for sheer entertainment.”

WILSON: “Wilson,” by A. Scott Berg

Woodrow Wilson is one of those figures who go in and out of fashion, and he is currently very much out of vogue. Nonetheless, this fascinating 2013 book by the best-selling author of acclaimed biographies of Charles Lindbergh and Katharine Hepburn tells the tumultuous and unlikely story of the rise and terrible fall of our 28th president, who catapulted from the presidency of Princeton University to the governorship of New Jersey and into the Oval Office, with shockingly little government experience. The book begins with Wilson’s victorious welcome in Europe for the Treaty of Versailles; the rest follows like a haunted Shakespearean tragedy in vivid novelistic prose.

Photo

F.D.R.: “No Ordinary Time. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, ” by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Continue reading the main story

This 1994 look at Franklin and Eleanor during the Second World War became a massive best seller for good reason. Written with the same historical nuance and narrative flair as her “Team of Rivals,” Goodwin’s book combines political, social and cultural history into a meaty (759 pages) but highly readable account of two extraordinary figures. As our reviewer noted, this story of a marriage is also an “ambitiously conceived and imaginatively executed participants’-eye view of the United States in the war years.”

EISENHOWER: “Eisenhower in War and Peace,” by Jean Edward Smith

Only a quarter of this book is devoted to Eisenhower’s presidency and beyond. Instead, the focus here is on the military experience that prepared Eisenhower for leadership: the ability to make do with limited means, to delegate authority, to cooperate with allies and keep up morale. It added up to a presidency marked by competence and stability. “Eisenhower’s greatest accomplishment may well have been to make his presidency look bland and boring: In this sense, he was very different from the flamboyant Roosevelt, and that’s why historians at first underestimated him,” the Yale historian John Lewis Gaddis wrote in his 2012 review. “Jean Edward Smith is among the many who no longer do.”

KENNEDY: “A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House,” by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

Schlesinger served in the Kennedy White House, but far from clouding this history of Kennedy’s presidency, his closeness makes his a unique account of the era. The brevity of Kennedy’s tenure finds its counterpoint in this encyclopedic chronicle of those tumultuous years: the victory over Nixon, the challenges from Moscow and Southeast Asia, the momentum of civil rights. Our reviewer’s only complaint: He wished the book had been longer than its thousand-plus pages.

JOHNSON: “Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson,” by Robert A. Caro

Robert Caro, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The Power Broker,” has written four volumes of his biography of Lyndon B. Johnson so far, with more to come — making the selection of just one of his installments a challenge. But then again, this book is an easy win. In the words of our reviewer, the former Times columnist Anthony Lewis: “The book reads like a Trollope novel, but not even Trollope explored the ambitions and the gullibilities of men as deliciously as Robert Caro does. I laughed often as I read. And even though I knew what the outcome of a particular episode would be, I followed Caro’s account of it with excitement. I went back over chapters to make sure I had not missed a word.”

Photo

NIXON: “Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man,” by Garry Wills

“It is no small undertaking to write about the intellectual history of the United States, provide an analysis of modern politics, and keep track of where Richard Nixon fits into it all. Therefore Wills’s book is very large.” That’s Robert B. Semple Jr. in the Book Review, taking stock of Wills’s extraordinary portrait of Richard Nixon, published in 1970, in the context of “a nation whose faith has been corrupted, whose youth knows it has been had, whose president is president only because he has been able to sell a sufficient number of equally deluded souls on the proposition that he can bring us together today ‘because he can find the ground where we last stood together years ago.’” Elsewhere in The Times, John Leonard wrote that “Wills achieves the not inconsiderable feat of making Richard Nixon a sympathetic even tragic — figure, while at the same time being appalled by him.” Nixon would serve nearly four more years before his resignation, but with regard to the verdict on his presidency, Wills had the last word. And still has it.

REAGAN: “ Reagan,” by Lou Cannon

This biography came out in the second year of Reagan’s first term, but its underlying theme, in the words of our reviewer — “that Mr. Reagan’s career represents a triumph of personality and intuition over ignorance” — stands the test of time. Cannon’s bracingly critical approach might strike a chord with current consumers of news: “Mr. Cannon pursues Mr. Reagan’s ‘lies’ and ‘ignorance’ relentlessly, from an occasion on which Mr. Reagan ‘freely lied’ about his acting experience and salary when he was breaking into Hollywood to his presidential news conferences which have become ‘adventures into the uncharted regions of his mind.’ The author is careful to make the distinction between ignorance and stupidity. Mr. Reagan, he says, has ‘common sense,’ but his photographic memory is cluttered with dubious information gleaned from his favorite periodicals, Reader’s Digest and Human Events.”

OBAMA: “Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance,” by Barack Obama

In 1995, Barack Obama was a writer and law professor in his mid-30s, with little evidence of the presidential about him. His memoir traces his roots; it doesn’t prophesy his future. (“After college in Los Angeles and New York City, he sets out to become a community organizer,” our reviewer writes. “Mr. Obama admits he’s unsure exactly what the phrase means, but is attracted by the ideal of people united in community and purpose.”) But Obama’s voice, its cadences now familiar worldwide, provides a through line from the writer who “bravely tackled the complexities of his remarkable upbringing” to the leader who embodied those complexities in the highest office in the land.

Continue reading the main story

The post 17 Great Books About American Presidents for Presidents’ Day Weekend appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Why Are Famous Writers Attending the World’s Most Important Security Conference?

From February 17 to 19, the world’s powerful will gather in the south of Germany for the Munich Security Conference (MSC), a key event on the global political agenda. Over 100 ministers, 30 heads of state, and key decision makers including Mike Pence, James Mattis, Angela Merkel, and Bill Gates will attend the conference at the 5-star hotel Bayerischer Hof. Anyone not security cleared as part of the conference will be unable to set foot on the premises. But this year, the doors to the conference have cracked open to permit a few new participants: writers.

For the first time in its 53 year history, the MSC will include literature panels as part of its program. In a series of public talks entitled “The Cassandra Phenomenon,” world class writers Herta Müller, David Grossman, and Wole Soyinka will add their voices to the debate about international security challenges.

While the inclusion of writers at this high-profile forum at a time that, according to the Munich Security Report 2017, “is arguably more volatile than at any point since World War II,” might seem surprising, it is also understandable. With the rise of illiberalism, post-truth politics, and transatlantic uncertainty, the very pillars of the West are being shaken. In times of turmoil, people often look to literature for illumination.

It is no coincidence that George Orwell’s 1984, a novel about a totalitarian regime that employs phrases such as “doublethink” and “newspeak,” has become a best-seller since President Donald Trump’s inauguration and senior adviser Kellyanne Conway’s use of the term “alternative facts.” Or that Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a dystopian vision of an ultra-conservative US where women are stripped of their civil rights, has seen a similar recent spike in sales. Interestingly, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that mystery benefactors had given away copies of both novels in bookshops this month, accompanied by a sign stating, “Read Up. Fight Back.”

Article continues after advertisement

Like Cassandra, who warned of disaster during the Trojan War, writers often take a longer view of issues. They are uniquely placed to examine and critique society from a removed perspective—as Don DeLillo once said, “The writer is the person who stands outside society, independent of affiliation and independent of influence.” All three writers involved in the MSC talks are known for their incisive, often critical, engagement with the politics, history, and cultures of their milieus.

Nigerian playwright and poet Wole Soyinka, the first African to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, has been a strong critic of Nigeria’s numerous military dictators and other oppressive regimes. Fellow Nobel Literature winner Herta Müller, who experienced Nicolae Ceaușescu’s repressive regime in Romania, advocates for dissidents resisting similar systems. Much of her work undermines the official communist narrative of modern history by representing perspectives from Romania’s German minority and encompasses themes of violence, terror, and the impact of the political on the personal. Finally, Israeli author David Grossman has been critical of his country’s policy towards the Palestinians, and addressed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in his 2008 novel To the End of the Land.

No doubt, these writers are well-equipped to discuss the issues of the day within the context of the MSC. But will the talks have any real impact? Even if writers can foresee the consequences of a society dominated by “newspeak” or controlled by men, do they have the power to make a difference, or fight back?

Writers, who convey complex ideas through a combination of reason and emotion, have lost their currency in an age where the 24-hour news cycle, sensationalism, and the simplistic rhetoric of mainstream politics dominate. Their ability to influence and shape society has declined. To quote Don DeLillo again, who famously expressed the growing ineffectiveness of writers in Mao II: “I used to think it was possible for a novelist to alter the inner life of the culture. Now bomb-makers and gunmen have taken that territory. They make raids on human consciousness.”

The move to include writers at one of the most important forums dedicated to “international cooperation and dialogue in dealing with today’s and future security challenges” could therefore be seen as an irrelevant one. After all, the defining thing about Cassandra is that no one listened to her. And indeed, the writers at the conference will be on the outside, engaging in public talks, instead of inside the private rooms where real decisions will be made.

On the other hand, these writers panels could signal a resurgence in the ability of writers to tackle the concerns of this year’s conference.

In 1976, German constitutional judge Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde wrote: “The liberal secularized state lives by prerequisites which it cannot guarantee itself. This is the great adventure it has undertaken for freedom’s sake.” In other words, the paradox of liberal society is that everyone must believe in it in order for it to succeed, while at the same time it cannot, by its very nature, force everyone to share its values.

As evidenced by the current political climate, this problem is more relevant than ever. The western world, which was some years ago seen as a stable bloc, is fragmenting, with the rise of far right populism and anti-intellectualism. But perhaps a solution to this so-called Böckenförde dilemma, the key to holding the liberal ideal together, is literature.

Literature and enlightenment are fundaments of liberalism, but there has been a gradual sidelining of writers and the humanities in favor of technocratic capitalism. Just look no further than the shift from Obama, an avid reader and writer, who has said that books helped him “get perspective” at the White House, to Trump, who has said that he does not read extensively because he can reach the right decisions “with very little knowledge,” plus “common sense” and “business ability.” Involving writers in important political conferences such as the MSC is a clear rebuttal to anti-intellectualism, and reinforces key liberal values like freedom of expression and plural discourse.

In addition, as the term “humanities” aptly implies, writers are invested in engaging human considerations—moral, ethical, emotional—of issues. Although the rise in populist movements in the US and Europe is in part due to economic factors, much of it is also a consequence of fear and self-preservation. For example, in the US, analyses show that although economics were important, it was “not economic hardship but anxiety about the future that predicted whether people voted for Trump.” Literature can help untangle the complexities of people’s lives and emotions and, as studies have shown, foster empathy: books are a key ingredient in an open, pluralistic, democratic society.

Literature provides a ripe forum for discussion and the exchange of ideas, which is being encouraged by this year’s MSC. As Habermas once proposed, public, critical discourse is imperative to a functioning, pluralistic democracy that is perceived as legitimate by its citizens.

Although the US and certain countries in Europe (Poland and Hungary) have already swung to far right populism and illiberalism, this year will be decisive for the rest of the continent, with upcoming elections in the Netherlands, France, and Germany. So it is heartening to see the MSC welcoming writers into the fold—and maybe Muller, Soyinka, and Grossman will have some ideas about how to swing things back to the middle.

The post Why Are Famous Writers Attending the World’s Most Important Security Conference? appeared first on Art of Conversation.

John Sibley Williams: Poet Interview

Please join me in welcoming John Sibley Williams to the Poetic Asides blog!

John Sibley Williams

John Sibley Williams is the editor of two Northwest poetry anthologies and the author of nine collections, including Disinheritance and Controlled Hallucinations. A seven-time Pushcart nominee, John is the winner of numerous awards, including the Philip Booth Award, American Literary Review Poetry Contest, Nancy D. Hargrove Editors’ Prize, Confrontation Poetry Prize, and Vallum Award for Poetry.

He serves as editor of The Inflectionist Review and works as a literary agent. Previous publishing credits include: The Yale Review, Midwest Quarterly, Sycamore Review, The Massachusetts Review, Poet Lore, Saranac Review, Arts & Letters, Columbia Poetry Review, Mid-American Review, Poetry Northwest, Third Coast, Baltimore Review, RHINO, and various anthologies. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Here’s a poem I really enjoyed from his collection Disinheritance:

November Country, by John Sibley Williams

My grandfather digs a double plot

with his bare hands in case winter

can be shared

though he knows grandmother will outlive

her heart’s thaw by a decade.

I could give him a shovel. Instead

I ball the half-frozen river’s slack

numb around my fist, tighten

into ice. I will try to be less

hard next time.

Here in the gray

and two-dimensional house

we know the answer to rain.

A perforated black

arrow of birds moves

southward, array. Shrill reports

from every side and from the sky

the trajectory of abandonment.

Our surfaces are like the river.

Our circles have learned

to grow edges and crack.

Even the birds

we compare ourselves to

have left us.

*****

Forget Revision, Learn How to Re-create Your Poems!

Forget Revision, Learn How to Re-create Your Poems!

Do you find first drafts the easy part and revision kind of intimidating? If so, you’re not alone, and it’s common for writers to think the revision process is boring–but it doesn’t have to be!

In the 48-minute tutorial Re-Creating Poetry: How to Revise Poems, poets will learn how to go about re-creating their poems with the use of 7 revision filters that can help poets more effectively play with their poems after the first draft. Plus, it helps poets see how they make revision–gasp–fun!

*****

What are you currently up to?

Apart from being a new father of twins, which, along with writing, sort of defines me now, I’ve just completed two full-length poetry manuscripts that I’m submitting to various contests and publishers.

Skin Memory is an amalgam of free verse and prose poetry that focuses on bodies—human, animal, celestial, landscape—and how they affect each other. Keeping the Old World Lit is a tightly structured set of poems that explores our relationship with history, nostalgia, and cultural and personal regret.

I loved reading Disinheritance. How did you go about getting this collection published?

I loved reading Disinheritance. How did you go about getting this collection published?

Thanks so much! I really appreciate that. Disinheritance was a bit more personal, more intimate, than most of my work, so there was a greater emotional risk when introducing it to the world. I’m genuinely touched when someone tells me it resonated with them.

Luckily, the publication process was quite simple. Although I experienced the usual and expected rejections from a few contests and major publishers, Apprentice House Press took it on within a few months of the manuscript’s completion. I wish I had a powerful or inspiring story to share here, but Disinheritance came together easily and found a publisher fairly quickly.

You’re the author of nine poetry collections. Do they get easier or harder as you go along?

Not to sound coy, but both.

Putting together my earlier chapbooks felt like a simpler process, but that’s likely because each was a unique entity with poems written to work together toward the same goals. Those earlier poems were envisioned as short collections. Also, and perhaps more importantly, back then I hadn’t really studied how other poets structure their books.

There’s a true art to making 50, 80, 100 poems read fluidly. There are so many interesting techniques one can employ to create threads for the reader to follow throughout an entire collection. And there is so much culling, so much editing, so many lovely poems that must fall to the cutting room floor for the sake of overall consistency and flow.

So the process of organizing a book has become almost as complex as the writing itself, though it’s also become far more fun and rewarding.

For the individual poems, do you have a submission routine?

Absolutely, and a rather strict one.

It’s taken me years of research and reading hundreds of magazines to create a thorough spreadsheet for my individual poem submissions. I keep notes on their changing editorial focuses and open submission windows. I do my best to match each poem with a few magazines that I feel might enjoy them.

And I track all submissions so that every poem I truly believe in is submitted to around five magazines at a time. It’s a time-consuming process, taking up at least a third of my creative time each week, but it’s worth it.

As a follow up, do you have a writing routine you try to keep?

I became the father of twins about six months ago, so I’m now carving out new, flexible routines that balance writing with life’s many other joyful responsibilities. I still write daily, though usually in fragments, in stolen moments, taking notes that will, hopefully, band together into poems.

I’m currently able to set aside about three days each week for true composition. To balance with the babies’ schedule, I tend to write for a few hours each weekend morning, just after dawn, and I’ve tweaked my full-time work hours a bit to allow me one or two afternoons of writing time.

As to the where of writing, when the notoriously rainy Oregon weather allows it, I prefer to write outside, in open-aired cafes or a nearby park that runs along the southern banks of the Willamette River.

One poet nobody knows but should. Who is it?

One poet nobody knows but should. Who is it?

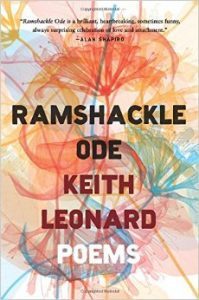

I shouldn’t assume what poets readers are or are not already familiar with, but one of my favorite books from last year that didn’t seem to make any of the Best of 2016 lists is Ramshackle Ode, by Keith Leonard. Admittedly, it was published by Mariner Books, so not exactly an unknown press, but I haven’t noticed much buzz in the poetry community about this incredible collection.

Each poem paints a fragile yet stubbornly persistent world, and somehow Leonard manages to both celebrate and eulogize life with a natural grace that feels so intimate, so familiar.

If you could pass along only one piece of advice to fellow poets, what would it be?

There’s a reason “keep writing, keep reading” has become clichéd advice for emerging writers; it’s absolutely true. You need to study as many books as possible from authors of various genres and from various countries. Listen to their voices. Watch how they manipulate and celebrate language. Delve deep into their themes and take notes on the stylistic, structural, and linguistic tools they employ.

And never, ever stop writing. Write every free moment you have. Bring a notebook and pen everywhere you go (and I mean everywhere). It’s okay if you’re only taking notes. Notes are critical. It’s okay if that first book doesn’t find a publisher. There will be more books to come. And it’s okay if those first poems aren’t all that great. You have a lifetime to grow as a writer.

Do we write to be cool, to be popular, to make money? We write because we have to, because we love crafting poems, because stringing words together into meaning is one of life’s true joys. So rejections are par for the course. Writing poems or stories that just aren’t as strong as they could be is par for the course. But we must all retain that burning passion for language and storytelling. That flame is what keeps us maturing as writers.

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is the editor of Poet’s Market and author of Solving the World’s Problems. Follow him on Twitter @robertleebrewer.

*****

Check out these other poetic posts:

You might also like:

The post John Sibley Williams: Poet Interview appeared first on Art of Conversation.