Roy Miller's Blog, page 253

March 7, 2017

14 Books to Read This March

Keggie Carew, Dadland

(Grove Atlantic)

Keggie Carew’s Dadland is a rare amalgam: It’s a memoir of the days her father Tom Carew spent as one of the dashing, daring “Jedburghs” during World War II and yes, I said memoir even though Keggie wasn’t even born during her dad’s greatest exploits. Through a combination of her father’s archives, reunions with the remaining “Jeds,” and her own observations of Tom Carew deep in dementia, the author pieces together a joint memoir/biography that tugs at the heartstrings even as it describes real feats of bravery, such as Tom’s parachuting into Occupied France with a tiny team to defy Nazis, and his incredible work in trying to maintain a free Burma. Throughout, Keggie Carew balances historical summary with personal anecdote. No wonder it won the Costa Prize.

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub columnist

Article continues after advertisement

[image error]

Duncan Barlow, The City, Awake

(Stalking Horse Press)

I’m always up for a novel that takes a basic noir setup and heads into increasingly weird or unsettling spaces with it: Brian Evenson’s Last Days, Laird Hunt’s The Exquisite, Joe Meno’s The Boy Detective Fails, and several of Laird Barron’s short stories all come to mind. Duncan Barlow’s The City, Awake is another memorable entry into this world: readers will note the presence of beleaguered detectives, mysterious assignments, and a femme fatale, but they coexist with doppelgangers, religious fanaticism, and sinister conspiracies.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

[image error]

Joan Didion, South and West: From a Notebook

(Knopf)

Joan Didion’s work is rooted in a precision of observation, the kind of thinking that strips a subject bare or turns it carefully in the light like a well-cut stone. South and West: From a Notebook affords us the opportunity to revel in the fabulous workshop of such writing—that is, her journals. While both of the included excerpts are the detritus of failed writing assignments from the 70s—one on the American South, the other on the Patty Hearst trial—what remains is a glittering sediment.

–Dustin Illingworth, Lit Hub staff writer

[image error]

Dan Egan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes

(W.W. Norton)

Many people smarter than me say the next big war will be about water. Already, skirmishes are erupting: in small towns where conglomerates like Nestlé buy up local water supplies without citizen input or in the occupied Palestinian territories, which boast the biggest aquifer in the West Bank to the consternation of nearby Israeli settlers. Dan Egan (one of those smarter people) has written The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, a terrifying book indicating that the Great Lakes, which comprise 20 percent of the world’s freshwater, are heading toward ecological collapse. With US environmental policy on the verge of its own unraveling, this book feels urgent to policymakers and laypersons alike.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributing editor

[image error]

Patty Yumi Cottrell, Sorry to Disrupt the Peace

(McSweeney’s)

Patty Yumi Cottrell’s debut novel, Sorry to Disrupt the Peace, is a story that focuses on estrangement and suicide—but despite the serious subject matter, it’s also quirky and funny. A 32-year-old woman returns home to investigate her adoptive brother’s death. “I needed to put his life into an arrangement that made sense,” Cottrell writes, and it’s a quest that makes for a compelling, emotional read.

–Michele Filgate, Lit Hub contributing editor

[image error]

Paul Josephson, Traffic

(Bloomsbury Academic)

As someone who has driven cross country over 30 times and lives in Los Angeles (acknowledged by many as “the driving capital of the world”), I know my fair share about traffic—sitting in it, suffering through it, avoiding it, changing routes or canceling plans because of it. And yet, from one of the recent crop of books from Bloomsbury Academic’s Object Lessons series, I discovered just how much I had yet to learn about it. These Object Lessons books are interesting little in-depth examinations and philosophical treatises on objects as disparate as cigarette lighters, hotels, questionnaires, eggs, drones, golf balls, shipping containers, and waste. Like many of the other authors in the series, Paul Josephson, through humor and intelligence, offers great insight. He makes reading about traffic much more pleasant than being stuck in it.

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributing editor

[image error]

Mathias Énard, Compass

(New Directions)

Mathias Énard, author of the groundbreaking, single-sentence, 500-page novel Zone, finally garnered France’s top literary honor—the Prix Goncourt—with this, his ninth novel. Énard has long been known as one of France’s most political and literary authors, and this book, described as a “poetic eulogy to the long history of cultural exchanges between east and west,” would seem to be a very timely release from a writer who has relentlessly and profoundly explored that relationship. Compass very well may be the book that makes Énard a star in English translation.

–Scott Esposito, Lit Hub columnist

[image error]

Kim Stanley Robinson, New York 2140

(Orbit)

The man who wrote the Mars trilogy is following up with one of the most exciting books in climate change fiction (or “cli-fi”) yet written. New York 2140 takes place 120 years in the future in a submerged New York City. Sea levels have risen 50 feet, turning lower Manhattan into a series of Venice-like canals and sending Wall Street moguls north to the Cloisters. Capitalism, social media, and tech crime continue to shape the city, and representatives from all three catalyze a series of events that jeopardize an already uncertain future. Sweeping in scope and shot through with a wry humor, this book is both immensely readable and timely.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

[image error]

Adrian McKinty, Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly

(Seventh Street Books)

It’s time to visit our favorite totally dysfunctional detective in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland again. Yes, Detective Sean Duffy is back, but things are different now: he has a family, and is attempting to take a vacation with wife, child, and his parents when the novel opens. Oh, and the book has another one of those awesome Tom Waits titles: Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly. That neatly summarizes another aspect of the plot: someone in Internal Affairs seems to be gunning for Duffy. And there is a man killed by a cross bow in front of his house. Everybody sold now? Jump in.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor

[image error]

Julie Lekstrom Himes, Mikhail and Margarita

(Europa)

This book is a timely gem. Since the promise of “the gulag” seems to be in the future of many, this is a must read. Bulgakov, Mandelstam, women’s rights, oppression, love, and artistic suppression provide a backbone from which this wonderful debut takes shape. Read it, and then (re)read The Master and Margarita, for an extremely rewarding few days.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

[image error]

Paul LaFarge, The Night Ocean

(Penguin Press)

We begin with Marina, a woman whose husband has escaped from the psychiatric hospital where he had been living and drowned in a nearby lake. But Marina does not believe her husband is dead, because she has picked up the trail of his obsessions—namely H.P. Lovecraft, the young teenage fan with whom the famous weird fiction writer spent a summer, and the thinly coded diary of their love affair, which may or may not be a forgery. This is a formally and emotionally limber novel that pulls you in as a black lake might, except that it’s also funny, and transformative, and illuminating—it’s a book of spells if I’ve ever read one.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub associate editor

[image error]

Elif Batuman, The Idiot

(Penguin Press)

Elif Batuman’s fiction debut subverts narrative and genre expectations at every turn: The Idiot is a coming-of-age story with no epiphany, a campus novel in which banality supersedes intrigue, a travelogue without wonder, a would-be romance tortured in the most unglamorous way—that is, primarily by dial-up connection and existentialism. It follows, then, that the voice of Selin, Batuman’s protagonist, is one of the most singular I have encountered in recent memory. Her preternatural intelligence never gives way to precocity, nor, in her growing disillusionment, does she become an insufferable A.J. Soprano-style nihilist. And Selin’s occasional lapses into undergraduate pretension are tempered by a surprising, deadpan wit. This is a book that will make you want to write long, inscrutable e-mails late into the night, just to find out what language can do.

–Jess Bergman, Lit Hub features editor

[image error]

Ruud Gullit, How to Watch Soccer

(Penguin Books)

Think you know how to watch soccer? Think again, jackass. Turns out you’ve only been watching the ball (rookie mistake) while legendary former Holland and AC Milan midfielder Ruud Gullit has been watching the whole game (pro move). Fear not though, Gullit is here to break your chains and lead you by the hand, naked and afraid, out of Plato’s cave with his masterclass on the art and science of reading a match: How to Watch Soccer. It promises to be a revelatory experience.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

[image error]

Louise Glück, American Originality

(FSG)

When one of the nation’s great living poets sets her observational eye on the state of the American letters—poetry specifically—it is for all of us to pay attention. Ranging in scope from the more rigorously theoretical to the deeply personal, Gluck is an essayist at once generous and sharp, and her insights into craft, classic American poetry, and the souls of the poets, are essential reading.

–Jonny Diamond, editor, Lit Hub

The post 14 Books to Read This March appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Nancy Willard, Prolific Children’s Book Author, Dies at 80

Nancy Willard in 1998.

Credit

Eric Lindbloom

Nancy Willard, a prolific author whose 70 books of poems and fiction enchanted children and adults alike with a lyrical blend of fanciful illusion and stark reality, died on Feb. 19 at her home in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. She was 80.

The cause was coronary and pulmonary arrest, her husband, the photographer Eric Lindbloom, said.

Ms. Willard’s 1982 picture book, “A Visit to William Blake’s Inn: Poems for Innocent and Experienced Travelers,” was the first volume of poetry to receive the Newbery Medal, the country’s highest honor for children’s writing. Illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen, it also received a Caldecott Honor as one of the best illustrated books of the year. It was the first time a Newbery winner was also named a Caldecott book.

Ms. Willard traced her weaving of fancy and realism to her upbringing. Her father was a chemistry professor who perfected a method of rustproofing; her mother, she said, was a romantic who read to her daughters during summer boating idylls.

“I grew up aware of two ways of looking at the world that are opposed to each other and yet can exist side by side in the same person,” Ms. Willard wrote in an essay in Writer magazine. “One is the scientific view. The other is the magic view.”

In “William Blake’s Inn,” she transformed the English poet and printmaker into a hotelier who keeps an inn for a host of imaginary guests.

Continue reading the main story

“Nancy Willard’s imagination — in verse or prose, for children or adults — builds castles stranger than any mad King of Bavaria ever built,” the poet Donald Hall wrote in The New York Times Book Review in 1981. “She imagines with a wonderful concreteness. But also, she takes real language and by literal-mindedness turns it into the structure of dream.”

He continued: “If you know children virtuous in imagination, give them this book in which ‘The Wise Cow Enjoys a Cloud’:

“Where did you sleep last night, Wise Cow?

Where did you lay your head?”

“I caught my horns on a rolling cloud and made myself a bed,

and in the morning ate it raw on freshly buttered bread.”

While she was best known for her children’s books, Ms. Willard also wrote novels for adults. In 1993 the Times critic Michiko Kakutani described her second, “Sister Water,” as “a luminous, lyrical novel about familial love and loss, a novel that almost literally hums with the power of her language.”

Nancy Margaret Willard was born in Ann Arbor, Mich., on June 26, 1936, the daughter of Hobart Willard, who taught at the University of Michigan, and the former Margaret Sheppard.

Continue reading the main story

The first texts she read, she said, were the labels on canned goods in her kitchen. (“They gave me an eclectic vocabulary: ‘spinach,’ ‘green beans,’ ‘registered trademark,’ ‘net weight.’ ”) She published her first poem when she was 7, she said.

Ms. Willard, an English major, graduated from the University of Michigan in 1958 and went on to earn a master’s at Stanford, with a thesis on medieval folk songs, and a doctorate at the University of Michigan. She taught creative writing at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie from 1965 until she retired in 2013.

Her first children’s book, “Sailing to Cythera: And Other Anatole Stories,” was published in 1974 after her son, James Lindbloom, was born. In addition to her husband, he survives her. (She published other “Anatole” stories, and James became a model for a character in several other books.)

Continue reading the main story

Ms. Willard had no illusions about her young audience.

“Writing a book of poems for children is like sending a package to a child at camp: The cookies are fed to the fish, the books are fly swatters and the baseball cards are traded,” she once observed. “You never know the use to which your gift — or your poems — will be put. if you’re lucky, children a hundred years hence will be skipping rope to them or muttering them over the graves of dead cats.”

While her style evolved, one ingredient remained integral.

“Most of us grow up and put magic away with other childish things,” she explained in Writer magazine. “But I think we can all remember a time when magic was as real to us as science, and the things we couldn’t see were as important as the things we could.”

She added: “I believe that all small children and some adults hold this view together with the scientific ones. I also believe that the great books for children come from those writers who hold both.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Nancy Willard, Prolific Children’s Book Author, Dies at 80 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Translation as Activism: An Interview with Philip Boehm

Philip Boehm greets me on a Skype call from Texas where he is visiting his father and where, as he says, smiling thinly, narrowing his eyes, “there are neighbors who voted for Trump.” As a critically acclaimed playwright, founder of the Upstream Theater in St. Louis, and multiple prize-winning translator, Boehm has built an astounding career giving voice to a whole host of German and Polish writers whose work is growing increasingly prophetic, and thus mandatory, by the day. Philip Boehm surrounded by Trumpists is an absurd image I’ll cherish for a while.

Boehm began his theatre career at the State Academy of Theatre in Warsaw, Poland, where he lived through the last several years of the Jaruzelski regime. Fluent in German and Polish, Boehm’s own biography, theatre training, and uncanny ability to “hear voices” in foreign languages make him a maverick in translating for an American audience the darker sides of humanity as recorded by Franz Kafka, Berthold Brecht, Christoph Hein, Gregor von Rezzori, and Nobel Prize-winner Herta Müller. Boehm’s work is the art of literary diplomacy—quite literally, and sometimes hilariously so, as the self-proclaimed “man from Texas” who was “raised to be nice” assured me during our conversation.

Philip Boehm is in conversation tonight with Tablet literary editor David Samuels, at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City.

Jennifer-Naomi Hofmann: The obvious question: How did you get into literary translation, what were the steps that led you there, and how did you learn to speak German and Polish well enough to translate them?

Article continues after advertisement

Philip Boehm: I got into translation by complete chance. I’m not trained as a translator. It started when I was living in Poland, where I was directing plays at the State Academy in Warsaw. A friend in New York told me they were looking for someone to translate Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina. It sounded like something I could do even while living in Poland, so I submitted a sample and, lo and behold, they chose it. So I translated Bachmann and once that happened people started coming to me. That’s how it’s been since.

I learned German in high school. My grandfather was from Austria, but I didn’t know him, so we didn’t speak German at home apart from a few snatches of it floating about in my father’s world. Polish I learned in Poland, where I’ve lived a lot longer than in any German-speaking country. But I translate a lot more from German because there is a market for it.

JNH: I have heard people claim that one does not have to be fluent in the source language to translate it. Do you agree?

PB: Speaking the language is a necessary but insufficient condition. You don’t just have to speak the language, you absolutely have to understand it. Otherwise how are you going to get the nuances right? And that’s only step one. The other thing is you have to be able to write it in your own language. This would be the sufficient condition. And this is where I talk about the overlap between my work as a theatre director and translator.

JNH: Tell me about how those two disciplines cross-pollinate.

PB: It’s a lot about envisioning. As a director there is usually a script and I have to imagine how to stage it and put it into a new world, or rather, create a new world. So it’s moving from the language on the page to the reality on the stage. Of course, in translation you’re also moving from one world to another world. It’s not just from word to word, but worlds have to be reimagined. So I spend a lot of time imagining these concrete details. Like what implement would Leo Auberg [in The Hunger Angel] be eating from? Was it an aluminum cup? Was it this, or that?

When I am staging a play I like to create a world that is concrete enough for a prop to be able to portray the world, not just fill the set as stage dressing. The rehearsal process is like the translation process, where I play around with different possibilities, ultimately settling on something. Sometimes I will rehearse the first scene until I find the right musical key. And that’s often what I find myself doing in translation, as well. I often rewrite the first pages over and over until I find the musical key. So there is imagining another world, and also the willingness to let yourself be taken somewhere. That is something I like to do.

But it’s also all about hearing voices. When I direct a play, I have to be able to hear the voices in the script in order to help the actors find it in themselves. And I also have to hear the voices in a text and make the translation work in English. There is a lot of talk in the theatre world about voice workshops. But I’ve always advocated for “hearing workshops” because I think the art of listening and hearing is important.

JNH: Hearing voices in your own language is one thing, but how did you learn to channel them from a language and culture that is not your own?

PB: I worked on a farm in Bavaria once, which was quite an experience, linguistically. And I lived in Berlin and worked at a foundry for a while, so I was exposed to a wide variety of Germans. But I’m sure I’ve also made terrible mistakes that will haunt me at some point.

JNH: Now I am curious to know what they are.

PB: In that first book I translated, Malina, I remember some “Germanist” wrote a paper on that translation and they took me to task for my translation of the word “Todesarten.” I was trying to work within the framework of what I thought Bachmann was doing at the time, playing with contemporary ad-speak, incorporating a lot of things in her prose. Instead of translating it as “ways of dying,” which seems so flat, I was trying to come up with something that Bachmann would have called an “aura,” and I came up with “death styles.” I’m not sure if I’d do that today. People got polemic about this word. Ingeborg Bachmann has this following that has very strong ideas about what should and shouldn’t happen with her work, and the same goes for some of my Kafka decisions.

JNH: Going through these texts with such a fine-toothed comb, you must encounter the occasional blooper on part of a Nobel Prize winner, as well.

PB: Yes, even the first edition of The Hunger Angel contained some mistakes with the Russian words she was using. I think Herta Müller was recording things and just writing words down as she had heard Oskar Pastior say them. The German editors should have looked it up but, you know, when Herta Müller writes something, German editors don’t tend to suggest corrections. My editor on the other hand, Sara Bershtel, doesn’t hesitate to offer suggestions to Herta Müller, or anyone else for that matter. Which is one reason she is brilliant at what she does. It was actually thanks to Sara that Herta Müller came into the English speaking market. She was publishing Herta long before she won any of these prizes.

JNH: What is your relationship with the living authors you translate? Can it get difficult?

PB: I usually have very good relationships with the people I translate. Some of these friendships I’ve maintained for over a couple of decades now. Ilija Trojanow is supposed to come over and we’re supposed to romp around Texas together. You know, go canoeing or something. That’s the latest plan. I can call most of them when I’m in the process of translating their work, but I try to limit the number of questions I have for them. The big authors know that at some point they are going to have to trust me. Also, Herta Müller and Christoph Hein don’t really speak English. But Ilija Trojanow speaks beautiful English. He could write in English actually, so I could send him passages and he could make suggestions others would not make.

There have been a couple of people that just weren’t accessible. And if it’s a first-time author who doesn’t understand the process, or if someone is armed with a dangerous amount of English, it can get a little complicated.

JNH: Speaking of complicated: Both Herta Müller’s original Atemschaukel and your translation, The Hunger Angel, had an immense impact on me, but in very different ways. One could say you have created an independent, brilliant work of art. Do you take ownership of your work’s artistic autonomy or do you have a different relationship to the text?

PB: Ownership is a strange word in these cases. Certainly, as many people have pointed out, as translators we strive for anonymity, but also for recognition. There is some tension there. I think, yes, it is important to take credit for work that is both autonomous and derived. These are not mutually exclusive things. Let’s say, just because I happen to like him, Carlos Kleiber would conduct a piece by Brahms. You’re hearing Brahms’s symphony, but in Carlos Kleiber’s version. They both have a claim there.

It’s tricky in the publishing world. For instance, in many cases publishers are reluctant to recognize the translator on the jacket of a book. Generally speaking, publishers used to want to downplay that the book was translated. There was a prejudice against translated literature, and I think there is still a vestige of this. But now, with the bourgeoning of translation programs and some growing interest in the actual act of translation from the academic world, it’s changing. And we’re thinking they should push for it, for the profession as a whole, but it’s awkward for me. I don’t have this self-marketing gene.

Personally, let me put it this way: A few years ago, Herta Müller and I were giving a reading at the Library of Congress. While we’re walking to the venue, she stops, bends over, and finds a perfect four-leaf clover—yes, she’s just remarkable like that. She gave it to me, and I keep it in my translated copy of The Hunger Angel. That is symbolic for how I feel about our collaboration.

JNH: In the afterword to The Hunger Angel you write that, in the novel, “innocent expressions are frequently filled with lethal content,” and that your task was to “preserve this fundamental displacement without adding undue dislocation.” Translating an author like Herta Müller, who is known for her metaphoric richness and semantic precision, what is the basis for your understanding of such coded texts and how do you adapt these elements into the English language?

PB: For some reason, which may have something to do with having lived in Poland, a lot of the work I have done, both in translation and in theatre, goes into very dark places: Into the holocaust, into the camps. I translated these accounts from the Warsaw Ghetto, for example—that took forever. It was a big book, so I’m familiar with their use of language; the state-sponsored euphemisms to cover up crime. Herta Müller shows people caught up in a linguistic world where the language doesn’t match the reality. In a way, for her, there is a kind of primal echo from when she was little, when she encountered words that not only did not match reality but actually masked it or were in opposition to reality, and were thus loaded with all sorts of potentially “lethal content.” She was used to living with that tension and it is something she portrays very well in her characters.

So for me it was, again, about being sensitive. It’s a matter of hearing, listening to that disconnect, and respecting the silence. The elisions in a sentence. I’m a man from Texas, and I try to be nice. I’m often softening my own speech. We’re all soft spoken in my family. My tendency is to want to soften something by having a word in front of what I’m saying. But I have to fight that tendency. That’s not Herta Müller’s world. And I have to hear what that is. Her sharpness, her strength is partly due to what has been cut out.

JNH: Not only do you have to teach the English-speaking public what that world sounds like you also have to make them understand why it is important. How is that going?

PB: Yes, and you do have to ask yourself: If Herta Müller hadn’t won these awards, would these books have been translated? And if they had, would they have been accorded the same critical reception? We’re lucky in a way. John Freeman, for example, has this insight into these books and what they are doing. But how many critics are like him? I sent the book to a couple of critics and there was no response. They don’t even care. I once translated a German radio play based on The Hunger Angel, and gave it to the NPR station in St. Louis. They didn’t care at all. The fact that this could be the premiere of a radio play by a Nobel Prize-winning author, and they couldn’t care less. So there is that. So it’s not just teaching the culture about this world, but also making it interesting to people.

JNH: Given the current political landscape in the US, it’s now more important than ever to be reading literature from countries that have traveled this treacherous political path before us. As a translator of such works, where do you see your responsibility as diplomat and educator?

PB: I think that responsibility precedes the act of translation. In fact, I have published a couple of op-ed pieces in the past year. The last time I was in Germany, we went to the Leipzig Book Fair and I wrote a short piece about how impressed I was that a couple of hundred thousand people were visiting this book fair. The whole city had shut down. Wouldn’t it be something if, in St. Louis, instead of traffic jams when the Cardinals are playing, the highways were backed up because there is a book fair at Busch Stadium? But that’s not all, the grounds for that book fair were used to house temporary refugees before they were resettled. That was the theme of this past year’s book fair. They were really putting their money where their mouth is because they are actually doing this. Compared that to the fear mongering—at that time it was still the primaries—of Trump, Cruz, et al.

A neighbor tells me that he hears “the Mexicans want to do this, they want to do that.” And I ask him if he speaks Spanish and he says, no. It is our job then to say, “Well, this is what this person is actually saying.” Translating becomes a way to help people with limited vision. Elsewhere I have written about the necessity of imagination. Imagination is the key to empathy, and if we’re not able to imagine peoples’ lives, then our empathy diminishes. Translation is a bridge that serves to enlarge imagination, to connect to the world. We’re impoverished without it. This is something I have been saying for years.

So yes, as translators we are both diplomats and activists. The sheer act of translation is one of engaging with a world outside of whatever world we’re in. You’re not going to find a lot of translators that are in favor of Brexit. I feel we need to be increasingly outspoken; the more insular cultures become, the more outspoken we need to be, lest that insularity makes our fears come true—which is actually what is happening right now.

JNH: One could say translators are literary diplomats.

PB: Quite literally, yes. There is a funny story. I was asked to translate a German screenplay by a Romanian author living in Berlin. He had written a play based on an American author’s film, lifting full passages from the original script. Because they had mutual friends it was understood that it was all going to fly. So I translated it and sent it off to the American writer. I get a call a few days later and he says something like: “You… I… I don’t know what to say about this. I mean, you obviously know, but this… half of the script, no, more than half is my writing! I don’t even understand cubism, much less postmodernism if that is what this is supposed to be!” There was a whole back and forth, with the Romanian author saying, “I don’t understand. Already in Romania in seventh grade we learn difference between character and author. What is this? I am comparing him to Lampedusa! Do they not understand how flattering that is?”

I was trying to calm them down. The American was talking about intellectual property and the Romanian had a completely different view. This was not a successful diplomatic mission. In the end, the American did not allow it and the Romanian said, “In that case you are no longer invited to play in my film!”

JNH: You recently translated Herta Müller’s essay “Germany and Its Exiles” for Freeman’s forthcoming “Home” issue. In it she revisits not only her own experience leaving Romania as a political refugee, but the bureaucracy and nomenclature of exiling as a whole. She coins the term “appropriate” (“zweckmässige”) immigrants, describes a state of “inner exile” for dissidents within their own countries, and criticizes the shameful treatment of exiles post factum. You translated the essay before the primaries. From the works you have been translating to your own experience living in Poland, did you see parallels to what is happening in the US right now?

PB: Yes, I thought the essay was a great choice for the issue, and I was very aware of how appropriate it was when I was working on it.

Just from my own experience living in Poland, I remember I had to report to the police when I wanted a visa, or sometimes they would call and were pretty mean to me. They were just these types of people; that kind of vanity mixed with power. Now I’m in touch with these Polish and other Eastern European writers, people like Oksana Zabuzhko, and I’m getting notes about how to survive living in an autocracy. Because they’ve experienced it.

Herta’s piece is about those people who made the decision to leave very early on, and claims that they should be the first to be applauded. So who are these people now? And how do we make sure this doesn’t go further? I just spoke to a friend in the State Department, and he said he believes in American institutions and that the weight of our democratic tradition, checks and balances, and government are strong enough to withstand this challenge. But, as you know, I have seen shaky things before. So at what point do we challenge that notion?

The weight of banishment is lost on us today, but for those who are banished it has profound psychological effects. In one of the first plays we did at the theatre, some 12 years ago, there is a scene where a woman goes to an unnamed Middle Eastern country and has an encounter with a Palestinian refugee who says: “What about my children’s future? Did it get lost somewhere, did it fall out of your shoe somewhere?” And Herta [Müller] has this line, “homesick for a future.” That is the theme here. The people who are asked to leave their own countries and those who are not being admitted into others, they are “homesick for a future.” How can we reduce their situation to a simple, “They want to get here because they want everything we have?”

JNH: Looking back to successful resistance in the past, the public protests that helped bring down the Berlin Wall in 1989, for example, grew out of a collective need, a desperation that was able to create a critical mass. Protests today, however, are based purely on moral and ideological arguments—much less effective reasons to mobilize the masses. What have you learned translating authors familiar with the first twitches of authoritarian regimes? What can we do?

PB: Great question. Critical mass is a good term. When the Iron Curtain fell, energy had been released elsewhere, starting with Gorbachev. The critical mass receiving that energy propelled that. But there was also a lot of self-interest in the protests. In our situation, however, I don’t think enough people feel sufficiently threatened. I think we need to work on various fronts: artistic, intellectual, as well as calling senators, voting, all of those things, and of course, protesting. I don’t have any illusions that the people who come to the theatre in St. Louis will become enlightened, but that happens to be where I’m working. And Herta Müller’s article, for example: the piece was chosen and maybe someone will read it. Then again, the people who read it are probably already in line with the argument.

But what do I do with the neighbor who voted for Trump? A designer I work with says he thinks the country should just break up because he doesn’t want to deal with the people who voted for Trump. I don’t think you can say that.

JNH: A large part of the work that needs to be done is, of course, making foreign literature accessible to American readers. Other than the translation prejudices you’ve mentioned, what are some of the roadblocks in terms of the American audiences’ tastes and preferences?

PB: American audiences are used to realism and logic. European audiences, because they have more practice perhaps, are able to take in things that are not necessarily linear, logical, and realistic. The American reader, I believe, usually wants the well-made book. The plot has to move. A German reader, on the other hand, will tolerate the digressions, the philosophical exposes of, say, Gregor von Rezzori. It’s similar to what happens in theatre. In Poland I staged three-hour plays with no problem. In the US, they all said, “We can’t sit through that!” I translated supertitles for a piece at Lincoln Center of a famous Polish adaptation of a Thomas Bernhard novel—four hours long, brilliant staging. The New York Times called the aisles “escape routes.” The same production won awards in Poland. The US audience is not willing to go on that ride. And it makes no sense, because these are probably critics who claim to admire Leonard Cohen, for example. But how can you accept a Cohen poem or accept Cubism and Surrealism in a museum, but not accept the same in literature?

If I’m going to make a generalization, there is a more pragmatic understanding of literature in the States, and what might be considered high literature here still has less reach than it does in Europe. These writers exist in the US, but do they get published? And if they are published, where and how? Hopefully that will change a little bit, people are more interested in translation nowadays. An interesting paradox is that someone like Roberto Bolaño, for example, has a big following in the US. But if he were a US writer, would he have gotten published?

The post Translation as Activism: An Interview with Philip Boehm appeared first on Art of Conversation.

March 6, 2017

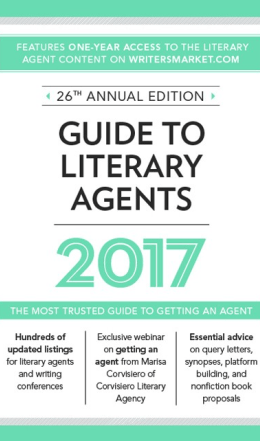

New Literary Agent Alert: Claire Easton of Painted Words

Reminder: New literary agents (with this spotlight featuring Claire Easton of Painted Words) are golden opportunities for new writers because each one is a literary agent who is likely building his or her client list.

About Claire: Claire joined Painted Words in 2012 as Lori Nowicki’s assistant, and worked her way up to being an agent. She studied English and Creative Writing at Binghamton University.

She is Seeking: Claire is looking for author-illustrated picture books, and also considers the occasional middle-grade and young adult manuscript. For any picture book, she loves humorous, character-driven stories; entertaining nonfiction; timeless stories that can be enjoyed at any age; and books that speak to the diversity of children’s experiences. For middle-grade and YA, she is open to all genres, as long as they story features strong characters and a unique voice.

How to Submit: Queries can be sent to submissions@painted-words.com. For picture books, please include the full manuscript or book dummy (if an attachment is over 5 MB, please send a link). For MG and YA, please send a synopsis and the first 10 pages of your manuscript.

The biggest literary agent database anywhere

is the Guide to Literary Agents. Pick up the

most recent updated edition online at a discount.

I f you’re an agent looking to update your information or an author interested in contributing to the GLA blog or the next edition of the book, contact Writer’s Digest Books Managing Editor Cris Freese at cris.freese@fwmedia.com.

f you’re an agent looking to update your information or an author interested in contributing to the GLA blog or the next edition of the book, contact Writer’s Digest Books Managing Editor Cris Freese at cris.freese@fwmedia.com.

You might also like:

The post New Literary Agent Alert: Claire Easton of Painted Words appeared first on Art of Conversation.

All Too Human – The New York Times

Similarly, Scruton contends, personhood is an “emergent” property of a biological organism. The critical shift occurs when the organism is complex enough to become self-conscious, when it is capable of conceiving itself as an “I,” and of grasping that other like-minded organisms also conceive of themselves this way. This is the human equivalent of the moment when the image of Lisa Gherardini arises from Leonardo’s paint: A new way of understanding ourselves and others like us comes into view. We become “persons,” whose actions make sense in terms of things like reasons and obligations and free choice — a different order of explanation than biologists have recourse to when talking about instinctive animal behavior. Science can offer powerful accounts of the relations between organisms — between an “it” and an “it” — but it cannot capture the understanding of us as we understand each other: as between a “you” and an “I.” For Scruton, this marks a radical separation of us from the rest of the natural world.

The idea that humans have a unique ability to act for reasons, as opposed to behaving like mere animals, also figures in THE WILD AND THE WICKED: On Nature and Human Nature (MIT Press, $29.95), by the environmental ethicist Benjamin Hale. Hale’s concern is how to “justify environmentalism — why we should preserve, defend or protect nature.” Hale finds the two main approaches to this question wanting. Groups like the World Wildlife Foundation and the Sierra Club argue that nature is intrinsically valuable: “grand and wonderful and awesome.” Hale dismisses this as naïve romanticism that ignores the inconvenient fact that nature is also “nasty and horrible and cruel.” But the alternative approach, prominent in today’s debates about climate change, is to view nature as instrumentally valuable, with human well-being and survival providing the justification for protecting the environment. Hale fears this approach loses sight of the guiding ethos of the environmental movement: its “concern for nature” as such.

Is there a third way? Can environmentalists avoid prioritizing human self-interest without succumbing to the temptation to anthropomorphize nature as having a humanlike dignity of its own? The trick, Hale argues, is to set aside the quest for a “guiding principle.” The trouble with our relationship with the environment, in his view, is not that we have the wrong values, but that we too often “don’t think about what we do” at all. His prescription is to focus on our human responsibility to “justify our actions,” our moral obligation “not to act like animals.” The mere process of deliberation and debate with others, the “justificatory struggle,” will lead to a higher environmentalism.

This suggestion is a bit confusing. It is not obvious how you go about justifying an action without having in mind some principle or objective in light of which it is justified. Indeed, Hale seems awkwardly aware that some people will find his proposal “empty and devoid of content.” What remains evident is his firm intuition that the human duty to nature is bound up in our status as the “sole bearers of responsibility on this planet.”

Continue reading the main story

For the literary theorist Terry Eagleton, the author of MATERIALISM (Yale University, $24), talk of human nature comes as a bracing tonic. For the past several decades, his academic field and its close cousin, cultural studies, have been dominated by what he calls “postmodern dogmatists” who see everything — especially so-called human nature — as a “cultural construct.” The assertion that “certain aspects of humanity remain more or less constant,” regardless of historical era or social conditions or prevailing ideology, is viewed, Eagleton complains, as not just incorrect but, as with all universal claims, “oppressive.” To suggest anything is fixed and immutable is thought to endorse a kind of political conservatism, a resistance to the potential for change and progress.

Eagleton’s book is a short, impish work of “unabashed universalism.” He devotes much of it to cursory discussions of three thinkers — Marx, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein — all of whom kept firmly in mind that human beings are part of the material world, and in that respect subject to nature’s unchanging laws. Even Marx, who is associated with the view that humans, unlike other animals, are historical beings, believed they were historical “invariably and without exception.” And Marx was not a conservative.

Continue reading the main story

Eagleton cautions his fellow leftists not to assume that those who oppose the idea of human nature are “always on the side of the political angels.” He stresses that as a matter of simple logic, mutability is “by no means a good in itself.” Stasis can be good; change can be bad. More to the point, he concludes, if “human creatureliness” is a fixed feature of the world, there is no sense in resisting it for political reasons.

Continue reading the main story

The post All Too Human – The New York Times appeared first on Art of Conversation.

IDW Taps Shelly Bond to Launch Black Crown Comics Imprint

Shelly Bond, the former v-p and executive editor of DC Entertainment’s Vertigo imprint, is joining IDW Publishing to oversee Black Crown, a new creator-owned comics and graphic novel imprint.

Authors and the first titles that will be published by Black Crown will be announced in July at the San Diego Comic-Con International. The books will begin being released in October 2017. Black Crown comics and graphic novels will be creator-owned rather than work-for-hire properties owned by IDW.

Bond, who started at DC’s Vertigo in 1993 as an assistant editor, as executive editor of Vertigo when Berger left in 2012. Bond directed Vertigo until April 2016 when she left after a restructuring at the imprint eliminated her position. During her time at Vertigo, Bond was responsible for overseeing a list of acclaimed nonsuperhero comics, among them such series as Fables, Sandman, iZombie and others. At IDW her title will be senior editor, special projects.

IDW chief creative officer Chris Ryall said he was " huge fan of the direction, vision, and creative teams Bond assembled on her books over the years."

Bond, speaking to her new job, said, "I can’t think of a better fit for Black Crown than with IDW. They appreciate, share, and champion my vision for creating concepts that are first and foremost incredible, unconventional, and riveting comic books."

The post IDW Taps Shelly Bond to Launch Black Crown Comics Imprint appeared first on Art of Conversation.

What Writers Should Do Right After Publication

For most of us, publishing our work is what we crave most. We probably assume that when we’ve reached this goal, we’re done with a particular piece. Not so. As you may already know, if we want to maximize the benefits of publication, we can do many things after the piece has appeared. Some are obvious (like posting on Facebook and exclaiming on Twitter), some you may already be doing, and a few may be new to you.

After you publish any short piece, consider taking steps in two main categories. I do these myself and think of them, broadly, as “external” and “internal.”

Guest post by Noelle Sterne. Author, editor, dissertation and writing coach, and spiritual counselor, Noelle has published over 300 pieces in print and online venues, including Author Magazine, Fiction Southeast, Funds for Writers, Children’s Book Insider, Graduate Schools Magazine, Inspire Me Today, Pen & Prosper, Romance Writers Report, Transformation Magazine, Unity Magazine, Women in Higher Education, Women on Writing, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer. She has also published pieces in anthologies, including Chicken Soup for the Soul books; has contributed several columns to writing publications; and recently became a volunteer judge for Rate Your Story. With a Ph.D. from Columbia University, Noelle has for 30 years assisted doctoral candidates to complete their dissertations (finally). Based on her practice, her handbook addressing dissertation writers’ overlooked but very important nonacademic difficulties will be published in September 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield Education. The title: Challenges in Writing Your Dissertation: Coping with the Emotional, Interpersonal, and Spiritual Struggles. In Noelle`s previous book, Trust Your Life: Forgive Yourself and Go After Your Dreams (Unity Books, 2011), she draws examples from her academic consulting and other aspects of life to help readers release regrets, relabel their past, and reach their lifelong yearnings. Her webinar about the book can be seen on YouTube. Visit Noelle`s website: trustyourlifenow.com.

External

Think of this category as anything outside your workspace. Even though your article may appear in a small (even obscure) publication, off- or online, it’s still an accomplishment and a credit. So . . . .

Write to the Accepting Editor

I think writers often take editors for granted. Editors have a hard job too, and many must plant themselves in sterile cubicles (or lonely home offices) surrounded by piles of submissions and impossible lists of tasks and deadlines. I make a point of writing the editor shortly after publication, after I’ve gotten the check and complimentary copies and bought another two dozen myself.

In my letter I thank the editor for the fee and issues, and I also praise (a) something about my article (other than the brilliant writing) and (b) something else in the issue. For example, I voice appreciation for the crisp layout of my piece or a photo that captures the essence. For other entries in the issue, I praise an author’s particularly helpful column, a moving poem, or an article that taught me something new.

Sometimes editors reply with gratitude, sometimes they don’t. Either way, I always feel good writing these notes. I believe the editors do feel appreciated and, even subliminally, will hold a special place for me as a considerate author in their hearts and hopefully on their editorial calendars.

[Get your creative juices flowing by trying this 12-Day plan of simple writing exercises.]

Tell Everyone

We writers may have a hard time self-promoting, especially if our piece appears in a publication no one but four depressed poets has ever heard of. Nevertheless, publication—any publication—is cause for pride (the good kind) and declaration.

Post your news, with a link, if possible, not only on Facebook and Twitter but also on your email signature, website, and any other social media you’re addicted to. Equally important, speak up to everyone you know or bump into. Announcement may take practice. You can be casual but purposive, in person or on the phone. For example:

Your friend: “Hi, how are you!”

You: “Great, thanks [don’t stop], and my latest news is that my essay on how not to let your child get in the way of your writing is published this month in Parenting Away.

Wait for the congratulations or squeal. Then lower your eyes, smile a little, and murmur, “Thank you . . . so much.”

Practice too on neighbors, salespeople, the supermarket grocery manager you’ve known for years. When I told a server in a local restaurant about my book Trust Your Life, to my pleased surprise she declared, “I’m going to buy three copies—for myself, my daughter, and my best friend.”

Create your own variations of your announcement. What to say and how will get easier and more natural, and you’ll be getting excellent practice for when your master tome hits the bookstores and talk shows.

[Do you underline book titles? Underline them? Put book titles in quotes? Find out here.]

Internal

This category is, obviously, anything you do inside. Some of my suggestions will sound like grunt-work, but they pay off.

Keep Good Records

We may scoff or groan at what seems like an accountant mentality about keeping records. After all, we’re creative. But, the greatest artists in every field can’t function without lists—of paint, brushes, solvents, notebooks, printer cartridges, pens, marble slabs, chisels, mud, mixing bowls, music paper. Not to mention computer folders and files and somewhat organized places for quick access to supplies in both scheduled creative sessions or ideas that descend with ferocious urgency.

Your system of cascading post-its may have been good enough for the acceptances you got once a year. But now you’re publishing more regularly(!). Please don’t rely on your memory or those scraps that can whirl like a tornado at the first sneeze.

Here are some suggestions that have long worked for me to keep good records.

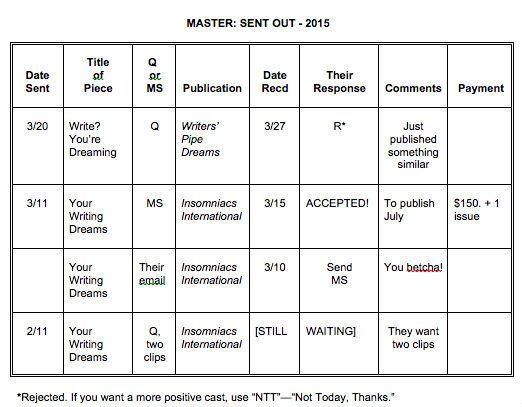

Track Your Pieces

As you send out your work, keep track of the titles, where you send, dates you send, and the responses. Various types of software are available for tracking. Free systems include SAMM (sandbaggers.8m.com/samm.htm) and Writing World’s fine, simple tracker (writing-world.com/store/year/index.shtml).

Fee-paid systems can be found at Duotrope (duotrope.com/index.aspx? bp=subtracker ) and WritersMarket.com. See also Robin Mizell’s helpful roundup of tracking software sites (robinmizell.wordpress.com/2008/02/18/submission-tracking-for-freelance-writers/).

Study what the different software programs offer and determine for yourself whether they’re too simple, complex, or totally unfathomable. Browse the Internet also for other programs; use keywords such as “writers’ tracking tools,” “writing query tracker,” “submission trackers,” “writing submission trackers.”

After studying several types of tracking software, you may choose to create your own system. Many writers use Microsoft Excel, but I’m allergic to it. I finally mastered the table feature in Microsoft Word and designed my own tables. I make one for each year, with columns that make sense to me (important consideration), and type the entries in reverse chronological order. A sample:

Keep a List of Credits

Kindly curb the whimpers. A list of credits can be invaluable, and the sooner you start the less you’ll have to catch up with. Think of this list as your writing resume. As you publish more, you can add to it (a great confidence booster).

I’ve arranged mine again in reverse chronological order and by year and month. Each entry lists the name of the piece, the publication, volume, issue, date, and, if the piece was published on the Web, the URL. If you prefer, order your list by genre—poems, essays, articles.

I also added a delicious section labeled “To Be Published.” Even if you have no entries right now, when you add this heading at the top of your list you’re affirming what will take place.

Make and Keep Good Clips

In the table above, notice the comment in the 2/11 entry in “Comments.” At the magazine’s request, I whipped off two sample clips of previous work. They were in my “Sample Clips” folder. Like your list of credits, your collection of clips has many uses (but that’s another article).

B.C. (Before Computers), I laboriously made hard copies of my articles at the nearest copy shop and tucked them into folders in one of my file cabinets. Today, electronics trump xerox.

The Miracle of the pdf. The portable document format is an unsung software miracle! You can convert anything to a pdf—meaning that a “picture” is taken of your work and cannot be altered.

The most well-known pdf software suite is Adobe Acrobat. You can get various packages with different levels of sophistication for a range of prices. Adobe is excellent, always upgrading, and with many tools for manipulating your pdfs.

Other pdf converters, called writers, are available and they are fine too—and free. I’ve used Nitro PDF Reader and Creator (http://www.nitroreader.com/) and CutePDFWriter (http://www.cutepdf.com/Products/CutePDF/writer.asp). Whatever software you download, play around with it and you’ll get to know how to use it.

Scan Scan Scan. Again, you have choices on scanning. My printer and scanner are HP, so I use HP “Solution Center,” which directs you to scan or perform other tasks. Microsoft also has scanning software.

[How to go from proposal to book contract in less than a week]

So, for your clips, if your article has been published in a hard copy-only publication, fold the issue carefully and scan the article into your computer (labeled properly, of course). Most of the time, the “scan document” choice works well, even with some graphics and an illustration. Otherwise, you can use “scan picture.” Aim for the sharpest image of the article.

I also scan in the issue cover and table of contents, showing my article title and name, of course. For your online publications in a magazine, journal, or blog, you can print and/or scan right from the site, again with the pdf choice.

Label each pdf of your published article by your name, title, publication title, number of words, and date of publication. Now save them all in your growing “Sample Clips” folder.

To Conclude, For Now

All of these steps and suggestions may seem like a lot of work. If you’re doing some of them already, congratulations! Once you recognize the importance of both the external and internal après-pub steps, you’ll be more willing to give them the necessary time to set up your procedures.

As you master your systems, it will get easier, I promise, especially if you log, scan, and file as you go. Then faster than a document converter and more elating than an editor’s “Yes!” you’ll be doing all the right things right after you publish and publish and publish.

Get the complete start-to-finish mega-guide to

Get the complete start-to-finish mega-guide to

writing your book with Novel Writing, a special

130-page bookazine from Writer’s Digest.

Download it now or buy it in print.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

Brian A. Klems is the editor of this blog, online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

You might also like:

The post What Writers Should Do Right After Publication appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Women Can Lead Lives of Quiet Desperation Too

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” goes Thoreau’s oft-quoted line from Walden. “What is called resignation is confirmed desperation.” This fits neatly into the category of lines from literature guaranteed to make me roll my eyes—not because Thoreau is wrong, necessarily, but because of how tightly we often cling to his rightness.

After all, in our culture, and especially on screen, it’s indeed usually men who get to lead lives of quiet desperation—I say get to but I mean are afforded the emotional agency to, since no one really wants that kind of life (after turning 18, at least)—or who, in their more amplified incarnations, get to be Byronic heroes, brooding on cliff sides in black capes, staring out into the infinite, meaningless, cruel, dark ocean. Dark as their souls, their pasts, the hair of their dead beloveds. Etc. At least, that’s how used to be.

Thoreau’s famous line comes from the first section of Walden, “Economy,” in which he complains of a culture of men becoming so mired in work and the lives they are societally expected to live that they forget to actually live. That is, that they are “so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them.” Run off into the woods like me instead, says Thoreau. Emerson’s mom will still make you snacks and do your laundry. But I digress.

Thoreau may have been right about one problem—that it takes too much work to make it in America, and too many people have to work too hard for too little—but I take issue with the idea of men leading lives of quiet desperation as it has been adopted in our culture. It’s obviously problematic as a social construct: among other things, it suggests that men are more prone to this kind of existential crisis than women are (hey, perhaps that’s because their intellects are valued more highly), and also that men shouldn’t express their emotions to other humans and therefore must stare out at the horizon to quietly feel desperate about them. Men, that is, are told that “quiet desperation” is a kind of manliness.

Article continues after advertisement

Even more manly, of course, is the Byronic hero: typically attractive, magnetic, intelligent, and moody, conflicted, self-critical, and jaded. Often haunted by his past. Often characterized by strong beliefs that seem detached from the norms of his world, and his drive to follow those beliefs are self-destructive. Often violent, but the misunderstood kind of violent. Like Byron himself, these men are “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

I can’t help, when thinking about men who lead lives of quiet desperation, but make some mental parallels with the idea of “the forgotten men and women of our country,” who Donald Trump promised in his 2016 victory speech “will be forgotten no longer.” We love to romanticize their desperation, but I’ll be shocked if Trump helps them. At any rate, none of those Americans live in the Monterey that Madeline (Reese Witherspoon), Celeste (Nicole Kidman), and Jane (Shailene Woodley) occupy in HBO’s Big Little Lies. Maybe some of the characters here would have voted for Trump, but only so as to get their millionaire’s tax break. And to be honest, Donald Draper is a better example of what I mean here than the blue collar American worker to whom Trump was referring: rich, successful, tortured, self-destructive.

In this show, Madeline, Celeste, and Jane (along with, to a lesser extent, Renata Klein, portrayed by Laura Dern) are leading lives of quiet desperation, too. And one of the many great things about Big Little Lies is that it allows these women to occupy this traditionally male character trope. It’s not surprising to me that the series is based on a book (a novel of the same name by Liane Moriarty). After all, though it’s rarer (though not unheard of) on screen, in literature, women are much more regularly portrayed in this way. Consider women written by Clarice Lispector, Claire Messud, Evan S. Connell, Paula Fox, Catherine Lacey, etc. But these are not women that are often given their own HBO series or feature films. (One example to the contrary, which may or may not suggest an emerging trend, is Kelly Reichardt’s recent film Certain Women, based on Malie Meloy’s Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It, also, incidentally, featuring Laura Dern.) Most of the time, on screen, women have it much more together than the typical Byronic or Thoreauian hero—or even when they don’t have it together, they have lost their minds in some much more extravagant or comedic way (as in My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend). How to Get Away With Murder’s Annalise Keating may fit the Byronic mold, but she’s pretty singular. Jessica Jones is pretty Byronic, but she isn’t the least bit quiet about her desperation.

More often on our screens, women are the ones waiting in the kitchen for their wayward husbands to come home, to change, to figure out their shit. They are the frame for someone else’s story; they are the living, breathing, emotional stakes. Sometimes this seems like a good thing: women are portrayed as the strong ones—they are less moody, less disorganized, less prone to random, rash acts. They are victims, even when they aren’t. It’s a similar cultural impulse to the one that has TV ad after TV ad showing a clueless husband set straight by his slim hoodie-clad wife, who smiles ruefully and puts whatever product into his hand.

But Madeline, Celeste, and Jane, could also be characterized as mad, bad, and dangerous to know—at least sometimes. I see all three of them as contemporary, realistic Byronic heroes, though each one has refracted the trope differently—Jane is haunted by her past, Celeste clings to self-destructive patterns, Madeline forces her left-of-center belief system through everyone else’s like a cudgel, all three of them are “moody” in the secretive, tortured sense, and importantly for the show, all three of them seem like they’re equally capable of killing someone or of getting themselves killed. It’s refreshing to see women in these roles.

In an early scene, Jane tries to explain her feelings of detachment to Madeline and Celeste: “Sometimes when I’m in a new place, I get this sensation. Like, if only I were here. It’s like I’m on the outside looking in. I see this life, and this moment, and it’s so wonderful, but it doesn’t quite belong to me… You guys are just right. You’re exactly right, and for some reason that makes me feel wrong.” Celeste looks at her with such intense comprehension. She understands completely. She has her own kind of desperation, and is perhaps, the quietest of the three, despite the fact that her story is the most terrifying, and the most compelling. Madeline’s desperation is less quiet—in this scene, she’s babbling away, refusing to delve beneath the surface with her two friends, but even she has an underworld.

Even the show’s opening credits underscore the translation of typical masculine emotional angst markers to these female characters, taking a traditionally gendered task—driving the children to school—and treating it with seriousness, as if it were the kind of opening montage you might expect from a similar show, if it were gender-swapped: men staring off into the distance, thinking moody, uncertain thoughts, as Michael Kiwanuka sings “Did you ever want it? Did you want it bad?” and “We can try and hide it, it’s all the same…” (This isn’t the only song that speaks to the theme—“Papa was a Rolling Stone,” which soundtracks the trailer and ends the 6th episode, is nothing if not a song about a Byronic hero leaving misery in his wake.)

The cars, of course, are key. A lot happens in those cars—questions, decisions, release, reveals, tears, disaster—which rings true; the car is certainly one of our primary locations for the quiet desperation of contemporary life: it’s a place where you can be alone in the world for the amount of time it takes you to get from one errand to the next. It’s a mobile emotional hood. The landscape too is evocative of introspection and serious emotional trauma: cliff sides abound—and at least one character fantasizes about throwing herself off one—the complicated metaphor of the ocean is constantly in the background, the cheeky closing and opening of the fancy homes’ automated blinds a nod to modernity. What I mean to say is that every part of the show is taking these women seriously. (That’s not something you’d have to point out about a male-fronted psychological drama, of course, but I’ll just leave that alone.)

In the end, though, this is a story about trauma and the aftermath of trauma, about abuse and the way we hide it, and not about the disconnected sense of self one feels when one has to work too hard for too little actual life. So I’d argue that in fact these characters are actually better at filling this trope in than their male counterparts—they’re desperate, yes, they’re unsatisfied with their lives, sure, but they aren’t just that. They’re also clawing their way into this world, holding on as best they know how. Which is, among other things, deeply entertaining to watch.

The post Women Can Lead Lives of Quiet Desperation Too appeared first on Art of Conversation.

At Media Conference, Murray Details HC’s International Growth

Continued investment in its global publishing ventures is one way that HarperCollins hopes to expand its operating margins, company CEO Brian Murry said at Deutsche Bank’s 25th Annual Media & Telecom conference held March 6 in Palm Beach, Fla.

HC now publishes in 17 languages and is continuing to build up its author services in the countries where it has divisions, Murray said. He told the crowd that, by the end of the year, he estimates foreign language markets will account for nearly 10% of the publisher's overall revenue, up from less than 1% before HC acquired Harlequin in 2014. Murray sees HC operating like a movie studio, with it developing content in a central location and then marketing and distributing that content around the globe.

Another growth area for the publisher will be digital audiobooks, which Murray said will grow by significant double digits this year. He said that given the rapid growth of digital audio he expects another significant player to get into the market to compete with Audible. At present, digital audiobooks generates revenue of about $50 million for HC.

Murray told the analysts that book publishing has weathered the digital transition well, and that a good balance between print and digital has been established. He said he is very happy with HC’s portfolio, explaining that about half of its revenue comes from its backlist and the remainder from the frontlist.

While the backlist is relatively steady generator of cash and profits, it is the unexpected hit that can give the company a real boon. And, although the Divergent remains the biggest home run the company has had in the last five years, HC still has surprise hits. Highlighting this, Murray pointed to the Hillbilly Elegy. The 2016 nonfiction title had a first printing of 15,000 copies and is now up to 1 million copies in print.

Another steady source of revenue is the Bible market which, annually, bring in about $60 million for the publisher. To ensure it remains competitive with the other major trade houses, HC spends about $200 million a year to acquire content, Murray said.

Asked if HC was on the lookout for more acquisitions, Murray said the company always has an eye out for “the right company that is the right fit at the right price,” but that no deal is eminent.

The post At Media Conference, Murray Details HC’s International Growth appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Cywydd Llosgyrnog: Poetic Form | WritersDigest.com

Just when you think we’ve uncovered every poetic form under the sun, we unearth another Welsh form–this time, cywydd llosgyrnog.

Cywydd Llosgyrnog Poems

Besides the spelling of the name, a poet can figure out this is a Welsh form pretty quick because it’s a syllabic-based form with internal rhymes. Here’s the structure of this six-line form (with the letters acting as syllables and the a’s, b’s, and c’s signifying rhymes:

1-xxxxxxxa

2-xxxxxxxa

3-xxxaxxb

4-xxxxxxxc

5-xxxxxxxc

6-xxxcxxb

So lines 1, 2, 4, and 5 are 8 syllables in length with lines 1 and 2 rhyming as well as lines 4 and 5. Lines 3 and 6 have 7 syllables and rhyme with each other; plus, line 3 has an internal rhyme with lines 1 and 2 while line 6 has an internal rhyme with lines 4 and 5. No other rules as far as subject matter or meter.

*****

Learn how to write sestina, shadorma, haiku, monotetra, golden shovel, and more with The Writer’s Digest Guide to Poetic Forms, by Robert Lee Brewer.

This e-book covers more than 40 poetic forms and shares examples to illustrate how each form works. Discover a new universe of poetic possibilities and apply it to your poetry today!

*****

Here’s my attempt at a Cywydd Llosgyrnog:

Daffodils, by Robert Lee Brewer

Daffodils don’t sway in the breeze

every time you hear old men sneeze;

instead, they tease spring awake

with their precocious happiness

in maintained beds and wilderness–

a simple dress for love’s sake.

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is Senior Content Editor of the Writer’s Digest Writing Community and author of Solving the World’s Problems (Press 53). Follow him on Twitter @RobertLeeBrewer.

*****

Find more poetic posts here:

You might also like:

The post Cywydd Llosgyrnog: Poetic Form | WritersDigest.com appeared first on Art of Conversation.