Roy Miller's Blog, page 250

March 10, 2017

Open Books: Poetry Spotlight | WritersDigest.com

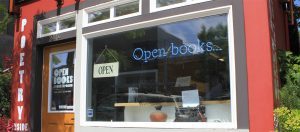

A month back, I posted on Berl’s Brooklyn Poetry Shop in New York; this week, I’m going to focus on a poetry bookstore on the West Coast: Open Books!

By the way, I appreciate the poetry spotlight ideas people have sent my way. Keep them coming at robert.brewer@fwmedia.com with the subject line: Poetry Spotlight Idea.

*****

The 2017 Poet’s Market, edited by Robert Lee Brewer, includes hundreds of poetry markets, including listings for poetry publications, publishers, contests, and more! With names, contact information, and submission tips, poets can find the right markets for their poetry and achieve more publication success than ever before.

In addition to the listings, there are articles on the craft, business, and promotion of poetry–so that poets can learn the ins and outs of writing poetry and seeking publication. Plus, it includes a one-year subscription to the poetry-related information on WritersMarket.com. All in all, it’s the best resource for poets looking to secure publication.

*****

Open Books: A Poem Emporium

Open Books: A Poem Emporium is located in Seattle, Washington, and it’s a 500-square-foot shop packed with more than 10,000 new, used, and out-of-print poetry titles, “as well as a selection of titles about poetry.” In other words, it’s a bookstore that specializes in one thing: poetry!

In addition to the poetry books, lovers of poetry can also find poetry events, including readings with both local and national poets. And, of course, this bookstore will celebrate its 22nd anniversary during the month of April (on the 28th to be precise).

Interested in buying books online? Open Books lists some of the better used book finds online. And if you’re in the Seattle area, the bookstore is open Tuesday through Saturday 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., as well as the first Sunday of the month from noon to 4 p.m.

*****

Robert Lee Brewer is the editor of Poet’s Market and author of Solving the World’s Problems. Follow him on Twitter @robertleebrewer.

*****

Check out these other poetic posts:

You might also like:

The post Open Books: Poetry Spotlight | WritersDigest.com appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Letters to the Editor – The New York Times

On the contrary: Women writing about women’s achievements in fields and institutions where they have been invisible and without voice has been instrumental in calling attention to their exclusion. Schwendener says that this kind of writing won’t “reverse the course of patriarchal art history.” Of course it won’t. But while one book won’t do it, many books, focusing as Donna Seaman does on the work and lives of women artists, can go a long way toward pointing to the desperate need for change.

Continue reading the main story

ANGELA BONAVOGLIA

MOUNT VERNON, N.Y.

⬥

Celebrating Our Illustrators

To the Editor:

I am repeatedly impressed by the combination of ingenuity and relevance of the art in the Book Review. The front-page drawing by Pablo Amargo, illustrating the lead review by Terrence Rafferty of “Six Four,” by Hideo Yokoyama (Feb. 26), is a case in point. It captures the unease of the central character within seemingly well-ordered Japan that the review suggests the crime novel conveys so well. At the same time the art is striking and dynamic, drawing the viewer into the central symbol.

STEPHEN M. JACOBY

CROTON-ON-HUDSON, N.Y.

⬥

To the Editor:

The graphics that accompany Book Review pages are always marvelous. Do these artists ever get any honors? Credits beyond the listing of their names? Praise for their extraordinary creativity? Because they are never explicitly celebrated, I feel that their work is taken for granted.

MITSI WAGNER

CLEVELAND

⬥

Reading for the Age of Trump

To the Editor:

Several articles and letters in the Book Review have addressed dystopian literature and the Trump administration. To these titles I would add Theodore Dreiser’s Trilogy of Desire (“The Financier,” “The Titan” and “The Stoic”). These novels are based on the life of the robber baron Charles Yerkes.

Continue reading the main story

The ruthless doings and outrageous behavior of the fictional Frank Cowperwood not only shed light on Trump but on the members of his billionaire cabinet as well. It’s a shame Dreiser’s works are largely unread today, especially in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse.

MARK KISSELBACH

PHILLIPSBURG, N.J.

⬥

More, Not Less

To the Editor:

Annie Murphy Paul, in her review of “Testosterone Rex” (Feb. 26), writes, “Built into the very structures of our thinking is the notion of women as less: less lustful, less competitive, less aggressive.”

Agreed, “women as less” is a source of injustice across cultures. But Paul’s list reinforces this bias. Isn’t being more lustful, competitive and aggressive exactly what’s wrong with maleness? Why venerate what testosterone does? I see women not as “less” lustful, competitive and aggressive but rather as more love-oriented, cooperative and peace-seeking. If that’s “less,” it’s certainly also more.

Continue reading the main story

To the extent that males and females differ in these things, women appear dealt the better hand. And if that’s just in my own personal pro-woman bias, I’m sticking with it. It seems to me that women have a lot to teach men about how best to be human.

CARL SAFINA

STONY BROOK, N.Y.

The writer is the first endowed professor for nature and humanity at Stony Brook University.

Continue reading the main story

⬥

‘Age of Anger’

To the Editor:

In his review of “Age of Anger,” by Pankaj Mishra (Feb. 19), Franklin Foer states, “Thanks to the advance of capitalism, we live in a world with less abject poverty, less disease, less oppression and greater material prosperity.” That such aspects of the world are better only because of capitalism is overly simplistic and perhaps plain wrong, given its displacement of hundreds of millions of people for arable land, cheap labor and natural resources.

Continue reading the main story

Mishra’s book has flaws, like its overreliance on Rousseau, but there is no “glibness” to his statement that “most people have found the notions of individualism and social mobility to be unrealizable in practice,” even in the United States, where mobility rates have fallen. His critique of global capitalism widens our understanding of its subjective as well as material effects upon an increasingly flat Friedmanian world.

JIM HANSON

COLLINSVILLE, ILL.

⬥

The Book Review wants to hear from readers. Letters for publication should include the writer’s name, address and telephone number. Please address them to books@nytimes or to The Editor, The New York Times Book Review, 620 Eighth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10018. Comments may also be posted on the Book Review’s Facebook page.

Continue reading the main story

Letters may be edited for length and clarity. We regret that we are unable to acknowledge letters.

Information about subscriptions and submitting books for review may be found here .

Continue reading the main story

The post Letters to the Editor – The New York Times appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Looking at America from the Trans-Siberian Express

Writer Rosa Liksom boarded a train in Siberia this past November and stayed in compartment no. 6 once again. The same trip 30 years ago was the inspiration for her novel Compartment No. 6 (Hytti no. 6), published in English in 2016 by Graywolf Press. Liksom won the Finlandia Prize for the novel in 2011. The following was translated by Mia Spangenberg.

______________________

What do Russia’s train stations look like now? How have Russia and its inhabitants changed?

The Trans-Siberian train arrives at Krasnoyarsk’s station at platform 4.

Article continues after advertisement

The conductor, a stylish lady, compliments me on my coat and with a smile leads me to compartment no. 6 and wishes me a pleasant journey. I put my backpack under the bed in the metal storage bin.

A young woman who looks like a hipster from Berlin sits on the edge of the other bed; her name is Mila. She’s on her way home to Moscow from a business trip in Irkutsk.

I go back out into the corridor to join other passengers who are chatting and milling about. The train is new—every nook and cranny is gleaming, even the samovar. There’s no smell. Smoking is not allowed, and the man standing next to me smells of Obsession aftershave.

The train rolls into motion, and the speakers softly begin to play Chopin’s prelude. A lively looking grandmother steps out of compartment no. 4 with her five-year old granddaughter in braids. Both of them wave at the people standing outside on the platform.

We leave Krasnoyarsk behind. Its main street is a mixed architectural wonder: there’s a dark, shiny skyscraper with a community garden quietly hibernating in its backyard. We leave behind a late constructivist concrete block, a new building built in Stalin’s socialist classicist style, and two Hrustsovka, brick apartment buildings built while Khrushchev was in power, with a dainty blue onion dome church squeezed in between them.

We leave behind the old Siberian banya on the outskirts of town, and the Soviet grannies who bathe there and covered my skin in salted honey, who whisked me with two birch branches and massaged me and threw water on the sauna stones with woolen hats on their heads and slippers on their feet.

We leave behind the trendy cafes and organic restaurants, the modern art museums, the clubs, the coffee snobs, hipsters, and dandies. There goes electric, pulsing Krasnoyarsk, a city which used to be closed and forbidden, and a feared staging area for deportation to labor camps.

The compartment features a small flat-screen TV and pretty reading lamps, and white cotton curtains hang in the windows, just like at a summer cottage. The table is covered in a white table cloth, and there’s a white vase with a yellow silk rose.

There’s also a white cardboard box for every passenger on the table. It’s been packed with a croissant, a muffin, a roll, jam, butter, cheese, a bag of black and green Lipton tea, and a rosy red apple. Two traditional tea glasses sit on their porcelain saucers. Passengers can retrieve hot water from the large samovar out in the corridor.

Mila’s phone rings.

“I’m not going to answer. My grandmother has already called me 20 times today. I just talked to her a little while ago and don’t feel like talking to her right now. I didn’t tell her that I am on a business trip to Siberia because she can’t stand them. She can’t sleep because she’s afraid something will happen to me.”

The conductor, whose name is Pasha, arrives in her snug uniform, which includes a dark blue skirt, a white shirt, and a dark blue vest. She shows me how to open the bed. It’s been made with white bed linens. Pasha tells me that the restaurant car is open, and that if I need anything, I should feel free to ask her.

I pick up the tea glasses and retrieve hot water from the samovar. Pasha sits in her compartment and watches an episode from a Russian TV series on her laptop. Mila and I put raspberry jam in our tea and open our muffin wrappers. Mila tells me that she is an English teacher.

“My father was a miner and died from alcohol abuse when I was little. My mother is an economist, and she moved to New York ten years ago. She fell in love, but then they broke up, and she ended up staying there. First she worked at McDonald’s, then as a cleaner, and now she works at a Russian investment firm. They told her she can have the job if she doesn’t steal anything! My mom is planning to return to Moscow. She loves the arts. She thinks Russia could brand itself as a superpower of culture. Not a bad idea!”

I ask Mila what kind of feelings she has about Soviet times.

“Foreigners always ask about Soviet times. What’s so interesting about that? I was one year old when the Soviet Union became Russia. I don’t know anything at all about Soviet times.”

Mila watches the scenery for a moment. We catch glimpses of a valley covered in a thin layer of snow reaching out towards the horizon between the birch trees. A narrow river courses its way through the valley, and the water steams in the current. The frozen sun colors the sky a hazy violet.

“My mom has told me that when the Soviet Union collapsed, my dad didn’t get paid for half a year, even though he had two jobs. My parents were fighting starvation because we didn’t have any family in the countryside to help us. Things got better for a while, but when the value of the ruble collapsed in 1998, we fell on hard times again when salaries weren’t paid. One time when my dad came home from work, he had a Swiss chocolate bar in his hand. His monthly salary had been paid with one chocolate bar. I clearly remember the wrapper. It was light blue and had a big round cow on it. My mom put the chocolate bar in a metal container on top of one of the kitchen cabinets. When I was home alone, I climbed up on a chair and took out the chocolate bar. Then I admired it at the kitchen table.”

We talked about life and the problems caused by globalization in Finland, Europe, and Russia.

“I followed the US presidential election on the internet. I was a Bernie Sanders supporter, and I was very disappointed when he lost to Clinton. In Russia, no one talks about equality and the common good, and how globalization could benefit everyone like Sanders does, and also Obama. Greed and corruption are completely acceptable and prized in Russia, as I guess they are in Finland, too. No one really misses the Soviet Union, but there are other alternatives in the world, like Bernie’s alternative. The middle class is disappointed, even though they still lead normal lives.”

“I’m just upset all of the Finnish cheeses disappeared from the shelves,” Mila laughs.

Pasha knocks on the door, and she enters with a small basket and an embarrassed smile. The basket contains souvenirs: some thumb drives and thermometers in the shape of a train, tea glass holders, and notepads. Mila buys a thumb drive.

After Pasha leaves, Mila explains that if the conductor wants to receive a bonus to supplement her small salary, she has to sell trinkets to the passengers.

Then she continues her story.

“Rich people and millionaires, and there are millions of them in Russia, live downtown in cities or in their own private, guarded compounds. They buy their clothes from fancy boutiques, and they have their own very expensive services everywhere: restaurants, gyms, department stores, beauty salons, resorts, spas, and so on. Those who aren’t doing so well live in the countryside, in small cities, or in suburbs on the outskirts of town. People look down on migrant workers from Central Asia and anyone without papers, even though they do all the shit work that isn’t good enough for any Russian. Society’s different classes never mix. The poor were angry for a while, but they’ve already given up a long time ago now. They’ve been abandoned to their fate.”

We decide to go to the restaurant car.

It’s decorated with red-gold curtains, plush benches and flowery tablecloths. There are only three other customers: a Mongolian woman with a model’s figure wearing a black dress paired with a blue fox fur collar, her two-year-old son, and her restless mother-in-law from Tula.

I order tea, and Mila orders a latte. The waiter smiles and says: “Unfortunately we don’t have a latte machine, but I can make you an espresso.” I receive a cup of hot water, a Lipton tea bag, and a slice of French bread, and Mila receives her espresso.

It’s so quiet and dreamy that we decide to return to compartment no. 6. It’s cozy and full of ambiance.

The beauty box I’ve been given contains all the toiletries I need, and I make my way to the restroom. It smells like pine forest air freshener. I wash my face with warm water and listen for a moment to the calm clanking of the rails. Mila has put on soft H&M pajamas. She sits on the edge of her bed with her iPad on her lap and surfs the internet. She responds to her emails, posts on Facebook, and puts pictures she’s taken of Irkutsk on Instagram.

“Can you believe this picture I posted yesterday has already gotten more likes than all of my other posts combined?”

She shows me a picture of her cat ripping a book on the floor.

The day starts quietly. I dress and watch the warehouse district flickering past outside the window. The train moves slowly and then stops at Novosibirsk’s train station.

Mila stays inside to sleep when I rush out with my camera. Pasha says that we’ll stop for 25 minutes.

The large, solid train station looks as if it has just been renovated. The emerald green buildings shimmer. The door to the entrance is still as heavy as it was 35 years ago. I slip inside.

Inside I walk through a metal detector that doesn’t seem to work. Five policemen in crisp uniforms are chatting among themselves and keeping an eye on it. The duty officer is stationed in his customary spot next to the metal detector. The elderly gentleman is wearing an official dark blue uniform. He looks relaxed as he sits behind the table and yawns.

Ten or so central Asian cleaners incessantly clean the floors. Some are pushing along cleaning machines, while others are polishing the doorknobs and railings. Here they don’t pretend to work. They actually work.

The kiosks sell icons, books, souvenirs, food, fruit, beer, clothes, and herbal remedies. A few people are sitting in the waiting area. Two policeman are inspecting the papers of a Central Asian-looking teenage boy, and something is amiss. They lead the listless but scared youth into a back room.

I walk outside and onto the passenger bridge that leads into town.

The sharp rays of the cold sun cut up the landscape. Bank billboards and digital advertisements flash from the tops of high-rise buildings. I don’t recognize the view anymore—old buildings have been torn down and replaced with dozens of new buildings. They look both humorous and cocky. Millions of LED lights watch the people as they rush to work.

I run back to the train. Pasha sighs with relief; I almost missed it.

Mila is dressed. She has already made her bed and is surfing on the internet. I go out in the corridor. A handsome young man named Elnur has boarded the train in Novosibirsk and is staying in compartment no. 5. He’s on the way to Tyumen and is eager to talk.

“Are you married?” I ask.

“Of course not. I’m still young, I’m only 28. I didn’t finish my studies, and I do odd jobs. Most recently I drove a truck. I was visiting my grandmother, and now I’m going to go visit my mother. My grandmother is Urdmurt, and my father’s mother was Azeri. I was born in Azerbaijan, but we moved to Moscow when I was five. My parents divorced, my father and I stayed in Moscow, and my mother moved with her new partner to Tyumen. I never want to live in Siberia. Everything’s better in Moscow.”

“Do you know that Trump will be the next American president and the most powerful person in the world? It’s bad news, it will bring war. Two roosters won’t fit in the same henhouse. Putin is a tough guy, he loves war. I was in the army for a year and seven months. They weren’t fun times. I was in the Nargorno-Karabakh War and had to shoot Armenians at close range. It was unpleasant, but in war you have to abide by war’s rules.”

“Obama was a good president. Trump is a racist and a fascist, but so is Putin. Still, Putin has managed pretty well in his position. He won’t let the West humiliate Russia. We want to be proud of our country, history, and culture. We want to be treated equally. We don’t want to end up on the outside, shivering by ourselves. We want to be part of the world and sit at the same table with Americans and shake hands. We’re all people here, all of us.”

Elnur goes off to call his mother and let her know he is on the train. Mila tells me a friend sent her a picture from Sheremetyevo Airport showing a cardboard statue of Vladimir the Great with a text that reads: Welcome home, Krim.

“My friend Sasha thinks that the Stalin-era propaganda machine has come back. And of course it is true that the government’s TV channels disseminate garbage and that people are too lazy to read the papers or to get information from the internet.”

Someone knocks on the door, and a waitress named Vania asks us if we would like to have dinner at 7 o’clock in our compartment or in the restaurant car. We choose to go to the restaurant.

I ask Mila if she has enough money to live a decent life. Mila looks at me with her head cocked to the side.

“When I get paid, I first buy trendy and high quality clothes or shoes, then some skin care products, and finally food with the rest—if I have anything left.”

When the train stops at the station in Barabinsk, Elnur, Mila and I rush outside. Trine, a Danish backpacker traveling in compartment no. 3, joins us.

The platform is utter chaos: fur traders run around offering their wares to critical travelers. Fried fish, frozen fish, smoked fish, dried meat, salted meat, barbecue steaks, woolen socks, and scarves are also on offer.

Elnur looks at me and grins.

“Those grannies are Finno-Ugric like you. You should buy something from your kinswomen so they can buy some vodka. They’re all alcoholics!”

Pasha calls out that the train is leaving, and we rush back inside. A disappointed trader gives me the evil eye from the platform and extends her middle finger.

Trine is a freelance journalist and a fan of Copenhagen’s Christiania, and she tells me she has spent ten days in North Korea. The trip cost 1,500 euros, and included full room and board as well as trips within the country and a guide.

There are enough of us to fill three tables in the restaurant car.

A man with a large belly, dressed in straight pants and a sweater, sits at one table with his small and slender girlfriend. Mila whispers that he’s a gangster. I ask her how she knows that. “He has an American Express card on the table, and only crooks and the new rich use that credit card.”

Grandmother Sonja and her son’s daughter Pauline are sitting at another table. I now notice that Sonja has a nose piercing. We’re sitting at the third table: Elnur, Volodya, who is sharing a compartment with Elnur, Mila, and me.

We have three choices for dinner: meat, fish, or vegetables. The men order meat, Mila vegetables, and I order fish. The wine is French, the food is good home cooking, and there’s plenty for everyone.

When we return to our compartments, we say goodbye to Elnur since the train will arrive so early in Tyumen that we’ll probably still be sleeping. I end up talking to Volodya, who has been reading in his compartment since he boarded the train. He’s a banker from Omsk, and he’s on a business trip to Moscow.

“Stocks went down 20 percent as soon as the results of the US presidential election were in. But it’s not a problem; they’ll stabilize sooner or later. Trump has investments in Russia, and it could have a positive effect on Putin’s and Trump’s relations. A businessman wants profits, and if he can get them in Russia, everything will be OK. The worst isn’t abjection or despair, but chaos.”

“Russia’s economy is in a tailspin. Many Western companies have left. Even Turkish businessmen have abandoned us because Putin doesn’t understand the first thing about the economy or about business in general. It’s sad. Where are you headed, Russia?” Volodya asks.

We watch the dense forest retreating into the freezing darkness and are silent for a while.

“I live with my wife in a house on the edge of town. I woke up yesterday at five, and when I looked out the window into the yard, I saw three wolves trotting along the edge of the woods. When it’s really cold they seek out humans. They kill stray dogs for food, and we kill the wolves. That’s how we keep things in balance.”

When I wake up early the next morning, the train has stopped. Mila is sleeping. I dress quickly and go outside. We’ve arrived in Yekaterinburg.

The sun winks at me from behind the steaming train station. People huddle in the freezing fog that has wrapped the city in its embrace. Well-fed strays are milling about on the platform; I count 16 of them.

I pick up a leftover roll and croissant from my compartment and throw them on the platform. A few dogs wander over to sniff at my alms but scurry away in disappointment.

Pasha watches me and laughs. “Those dogs aren’t after pastries, only meat is good enough for them!” An old, feeble little dog returns to the offerings and nibbles at the croissant as if offended.

I return to my bed, read a book, fall asleep, read again, fall asleep, draw, and rest.

I look at the valiantly persevering villages enveloped in the mist of the cold light. Some of them have been abandoned, and some of them have gone through the facelift brought by the euro. I glance over at the top bunk. Mila is watching a movie with headphones on. One station after another whizzes past compartment no. 6. We pass Perm, and dozens more little stations along the way.

Vania appears at the door with a basket full of warm potato perushky. We buy two juicy perushky and have them with some tea.

In the evening we arrive in Udmurtia, in the small town of Balezino. Mila doesn’t feel like going out, but Trine joins me. The thermometer reads -22 C.

Blue booths appear in the middle of stately snowbanks, as if torn from the pages of a fairy tale. They sell knitted plush toys, handmade knickknacks, Snickers and Mars bars, Oreo cookies, Coca Cola and ginger ale, porn magazines and romances, outerwear, and souvenirs.

Trine tells me she enjoyed her trip to North Korea, but she sounds slightly sarcastic. She has never been on a trip where things were made so easy. She didn’t have to do or think about anything.

Back in the compartment, Mila tells me she’s read that there will be a supermoon in the sky the next evening. The last one was seen in 1948. The news spreads, and soon we all start to really look forward to it together.

A man who looks like Pierce Brosnan joins Volodya in Balezino. Boris is a taxi driver on his way to Nizhny Novgorod. We talk in the corridor the next day, and Boris tells me he was born in the province of Krasnoyarsk, in the city of Norilsk.

“My father was Latvian, and he was deported to Norillag labor camp after the big nationalist war. He was freed after Stalin’s death, stayed in Norilsk, got married, and so I was born.”

In the evening almost all of the passengers are standing in the corridor waiting for the supermoon.

The sky is clear, the train is racing along its tracks, the snow is billowing, the stars are twinkling, but there’s still no sign of the supermoon. Then, before we reach the train station in Kirov, Boris shouts from his compartment. Mila and I rush over, and there it is: the pale neon orange disc covers half the sky and shines with a surreal glow.

“It shines its light over the guilty and the innocent, the victims and the criminals alike,” Boris says.

Before we return to our cozy compartment no. 6, we say goodbye to our traveling companions. There are selfies and big hugs. Mila and I play our favorite songs for each other on YouTube, and we listen to CNN News.

Mila says that compared to Trump, Putin is beginning to look like a humanist, and she’s really looking forward to returning home to her cat and her boyfriend.

“Irkutsk has good lattes and amazing sushi restaurants, but everything is still better in Moscow.”

The post Looking at America from the Trans-Siberian Express appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Riggio Reiterates B&N’s Commitment to Restoring Growth

As one of the featured speakers at the Association of American Publishers annual meeting held March 8 in New York, Barnes & Noble CEO Len Riggio delivered something of a bookselling history lesson, as well as his vision for the future of the country's biggest bricks and mortar book retailer.

In conversation with Penguin Random House CEO Markus Dohle, who conducted the Q&A, Riggio was clearly someone the audience wants to succeed. (After announcing his plans to retire from B&N in April 2016, he took back control of the company he founded in August of the same year).

Speaking only six days after the release of disappointing third quarter results (in which he said he has yet to find a “magic bullet” to stop B&N's sales slide), Riggio repeated that turning around negative comparable store sales into positive comps at the company is key to its future. Riggio said he thought B&N was on its way to achieving positive comps, but the distraction caused by the presidential election and its aftermath ended the upward momentum.

B&N remains comitted to being a multichannel retailer, Riggio continued, offering customers books through its physical stores and e-commerce website. He said the back end of BN.com, which had had a string of problems, is now “secure,” and the company has a great team of new people who have BN.com on track.

Riggio acknowledged that B&N’s expansion into manufacturing digital devices was a mistake, saying, "we’re not a technology company.” And the Nook unit, which at one point had as many as 1,600 employees, he said is now, after dramatic cuts, at about the right size, selling devices manufactured by third parties, but that carry the Nook name. Riggio said that while Nook is significantly smaller, he still wants B&N to be able to sell customers an e-book if that is what they want. On the topic of online sales versus in-store sales, Riggio noted that B&N does "a huge amount of business” from customers who order books online and then pick them up in a store.

In a reference to Canadian retailer Indigo Books & Music, Riggio said that CEO Heather Reisman has done a great job turning around the company (which posted strong 2016 results), by making the retailer a cultural store. But Riggio said making B&N a cultural department store “is not in our DNA.” He said books, which account for about 80% of B&N's sales, will remain central to the company.

Asked by Dohle what publishers can do to help B&N succeed, Riggio suggested that more heads of houses could visit B&N’s headquarters to explore new ideas. He also advised publishers not to fixate on B&N but, rather, on what their customers want. To this end, he suggested publishers should visit more stores outside of major cities.

The final piece of advice Riggio offered to publishers was to inject new life into the steadily declining mass market paperback business. He said at one point mass market paperbacks outsold hardcovers by a seven-to-one ratio. Riggio said with their low price points, mass market paperbacks are an entry format for many customers.

The meeting, in addition to offering a platform for Riggio to discuss B&N, served as the formal transfer of power from Tom Allen as AAP CEO to Maria Pallante, the former U.S. Register of Copyrights, who was selected to succeed Allen in January. In very brief remarks, Pallante said she will work to articulate the value of publishing to the public and will focus on such key areas as copyright protection, free speech issues, and trade.

The post Riggio Reiterates B&N’s Commitment to Restoring Growth appeared first on Art of Conversation.

March 9, 2017

Reading by Numbers – The New York Times

Credit

Joon Mo Kang

It was only a matter of time before big data came for literature.

Ben Blatt’s new book, “Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve,” slices and dices the texts of classic and contemporary books to generate charts and graphs with titles like: “Use of Exclamation Points per 100,000 Words in Elmore Leonard’s Novels.”

“You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose,” Leonard once wrote about the enthusiastic punctuation mark. He actually used 49 per 100,000 words, according to Blatt, but that still makes him the stingiest of the writers Blatt surveyed. You might guess Tom Wolfe would be the obvious leader of the exclamatory pack, and he’s close. But his 929 per 100,000 words comes in second to James Joyce’s 1,105.

Who uses the most clichés? (Like much else in Blatt’s book, the definition of cliché is both explained at length and open for debate.) James Patterson has the highest rate, and Jane Austen the lowest, but there are still surprises. Veronica Roth, author of the best-selling Divergent series, relies on them less than William Faulkner did, and F. Scott Fitzgerald called on them more (just) than Ayn Rand.

Blatt studied applied mathematics at Harvard, and while some of his charts require wonky parsing before diving in (Percent of Non-Neutral Speaking Verbs That Are “Loud”), others are immediately understandable, like the one showing that after a critically acclaimed debut, 72 percent of novelists publish a longer second book.

Continue reading the main story

Quotable

“Fiction stymies me with its possibility. In nonfiction . . . the constriction turns it into a puzzle, and I love puzzles. I would rather transform or solve something than invent it, I guess.” — Melissa Febos, author of “Abandon Me,” in an interview with the Rumpus

From Sherlock to Melrose

Benedict Cumberbatch — Oscar-nominated actor, Sherlock Holmes avatar and widely adored dreamboat — has signed on to star in and executive produce Showtime’s “Melrose,” a five-part adaptation of Edward St. Aubyn’s highly acclaimed series of Patrick Melrose novels.

David Nicholls, who has adapted Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens for the screen, in addition to his own novel “One Day,” will write all five episodes.

In The Times, Michiko Kakutani wrote about St. Aubyn’s “remarkable” series: “The books are written with an utterly idiosyncratic combination of emotional precision, crystalline observation and black humor, as if one of Evelyn Waugh’s wicked satires about British aristos had been mashed up with a searing memoir of abuse and addiction, and injected with Proustian meditations on the workings of memory and time.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Reading by Numbers – The New York Times appeared first on Art of Conversation.

David Cully Named President at B&T

Follett Corporation has named David Cully president of Baker & Taylor, effective April 1. Cully replaces George Coe, former president and CEO of B&T, just weeks after Coe was named COO of Follett.

In his new role, Cully will lead and manage all operations of the Baker & Taylor retail and public library businesses, and work to expand Baker & Taylor’s market presence and role in Follett’s growth plan. He will report to Coe.

“David has a strong background and extensive experience in retail sales, merchandising, marketing and supply chain with in-depth knowledge of the business,” Coe said in a statement. “His unique qualifications make him the ideal candidate to lead and grow the Baker & Taylor business for long-term success.”

Cully, who joined B&T in 2008, most recently served as executive v-p of its merchandising and digital media services division. He formerly held a variety of leadership positions at companies including Barnes & Noble and Simon & Schuster.

The post appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Marilyn Young, Historian Who Challenged U.S. Foreign Policy, Dies at 79

Marilyn B. Young in 2007. She remarked in 2012 that the United States had been at war in one form or another since her childhood.

Credit

Robin Holland

Marilyn B. Young, a leftist, feminist, antiwar historian who challenged conventional interpretations of American foreign policy, died on Feb. 19 at her home in Manhattan, where she was a longtime professor at New York University. She was 79.

The cause was complications of breast cancer, said her son, Michael.

Professor Young’s political consciousness was rudely awakened as a Brooklyn teenager in 1953, when she defied her father and watched from the fire escape of her family’s East Flatbush apartment as thousands of mourners gathered for the funeral of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who had been executed two days before at Sing Sing Prison for conspiracy to commit espionage.

“Get back inside,” her father yelled, a friend recalled. “The F.B.I. is taking pictures.”

The government’s aggressive pursuit of Soviet spies and her father’s trepidation set her on a course from which she never deviated: writing editorials for the Vassar College newspaper against red-baiting and favoring civil rights for blacks and political opportunities for women; researching a doctoral thesis that re-evaluated historic United States relations with China; and laying an anticolonial foundation for her opposition to the wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

Describing the United States as “a nation dedicated to counterrevolutionary violence,” she wrote in The New York Times Book Review in 1971 that “the most agonizing problems of recent American foreign policy have concerned not our ability to reach accommodation with acknowledged big powers, but our persistent refusal to allow revolutionary change and self-determination in smaller ones.”

In one form or another, she explained in 2012, since her childhood the United States had been at war — “the wars were not really limited and were never cold and in many places have not ended — in Latin America, in Africa, in East, South and Southeast Asia.”

Continue reading the main story

She described her evolving foreign policy until then as “anti-interventionist” — a policy she forswore, however, when it came to advancing the causes she cared about.

She was born Marilyn Blatt on April 25, 1937, in Brooklyn to Aaron Blatt, a postal superintendent, and the former Mollie Persoff, a school secretary.

She graduated from Samuel J. Tilden High School, earned a bachelor’s degree in history from Vassar in 1957 and received her doctorate from Harvard. Her dissertation became, in 1968, her first book: “The Rhetoric of Empire: American China Policy, 1895-1901.”

She also wrote “The Vietnam Wars, 1945-1990,” published in 1991, in which she called the conflict a revolution driven by anti-foreign nationalism. The Cornell historian Walter LaFeber described the book as a “deeply researched, detailed, well-written and outspoken account that should help shape how serious people view the Vietnam wars.”

Continue reading the main story

She married a fellow graduate student, Ernest P. Young. They moved to Japan, where he was a speechwriter to the American ambassador, and then to Ann Arbor, Mich., where both became professors at the University of Michigan. They separated in 1976 and later divorced.

In addition to their son, Michael J. Young, the president of the New York Film Academy, Professor Young is survived by a daughter, Dr. Lauren Young, a psychologist; three grandchildren; and her sister, Leah Glasser, a dean at Mount Holyoke College.

Continue reading the main story

Professor Young joined the faculty of N.Y.U. in 1980. She founded its Women Studies Department, was chairwoman of the history department from 1993 to 1996 and was co-director of the Center for the United States and the Cold War at the Tamiment Library. In 2011, she was elected president of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations.

“I find that I have spent most of my life as a teacher and scholar thinking and writing about war,” Professor Young said in her presidential address to the organization. “I moved from war to war, from the War of 1898 and U.S. participation in the Boxer Expedition and the Chinese civil war, to the Vietnam War, back to the Korean War, then further back to World War II and forward to the wars of the 20th and early 21st centuries.”

“Initially, I wrote about all these as if war and peace were discrete: prewar, war, peace or postwar,” she said. “Over time, this progression of wars has looked to me less like a progression than a continuation: as if between one war and the next, the country was on hold.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Marilyn Young, Historian Who Challenged U.S. Foreign Policy, Dies at 79 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Paul La Farge and Ed Park: In Praise of the Old School Cold Take

Paul La Farge ’s new novel, The Night Ocean , is inspired by an episode in the life of the great horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. His editor at Penguin Press, Ed Park, has long been familiar with La Farge ’s work, having edited dozens of his pieces in assorted publications.

Ed Park: I’m just looking up some past articles we worked on together—there are a lot of them! I’m struck by the fact that you were part of the very first Village Voice section I got to edit, as well as the very first issue of The Believer, a magazine I worked on for eight years.

Paul LaFarge: And you were the first editor I wrote anything for! I think the first piece I wrote for you was “In Search of the Fur Bat,” about the history of psychic research at Stanford; then I wrote an essay about the artificial language Volapük, which had about a million speakers in the 1880s, before Esperanto was invented. Later I wrote a short story about a school called “Bleak College,” which was, well, bleak. And those were all in the Village Voice’s Educational Supplement!

I loved working on those essays, and I didn’t know much about how things worked at the Voice, but I have to say, even then I was amazed that you let me write all those pieces. Now that I’m older, and I’ve written for other magazines, I am even more amazed, in a good way. Who else would ever have assigned me an essay about Volapük?

Article continues after advertisement

EP: I remember getting that first Voice piece, and smiling at the first sentence: “Stanford University’s Spanish Revival campus sprawls between Palo Alto and the foothills of the coastal mountains like a training center for Taco Bell franchise owners, a gigantic testament to the incompatibility of money and taste.”

PLF: Yeah, I’d just dropped out of a PhD program at Stanford, and that was my sense of the campus. But remember, I was coming from New York, and I had a lot of prejudices about California. Most of which I’ve outgrown, although I still think the Stanford campus is kind of quietly garish.

EP: I just did a double-take looking at that piece. It says that we published it 17 years ago. But we knew each other even before that.

PLF: We had the same writing teacher! I took an undergraduate writing workshop with Maureen Howard, who was just wonderful—in fact she was so wonderful that I’ve never taken another writing class. You studied with Maureen in a different class. And I’d stayed friends with her, and whenever I’d go to see her, at her apartment on Central Park West, she would tell me what a great writer you were, and how smart you were, and I’d sit there and drink tea and listen to her rave about you. I have to say that I was a little jealous. And then somehow, because of Maureen, I think, you sent me something you were working on, about Atlantis. And I had to admit that she was right.

EP: You wrote what I still believe to be the best single piece about Dungeons & Dragons ever published: “Destroy All Monsters,” which is collected in Read Hard, an anthology of Believer articles. Is it fair to say you got obsessed with the assignment?

PLF: Ed, thank you! That essay was a piece of utter madness. I wrote a letter to Gary Gygax, one of the inventors of D&D, to ask if my friend Wayne and I could go out to Wisconsin and play D&D with him, and to my amazement, he said yes. So we went out to Lake Geneva and played and talked to him for a couple of days. Then I came back and spent months and months reading about D&D and talking to people who’d been involved with the game in its early days, and also to people who’d known Gary when he went off to LA to become a movie producer—and then I had to go to LA, to see the vacant lot in Beverly Hills where King Vidor’s mansion used to stand—that was where Gary had lived. And it just went on from there. I think the essay took a year to write, which at the time seemed like a normal thing. You know, just another of those essays that you work on for an entire year. But in retrospect I can see that I’d become obsessed.

EP: It occurs to me that The Night Ocean is making a similar play for a cult or niche audience, the many people interested in Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos, as well as those who don’t know about him or in fact dislike him. (A recent review begins, ” I’ve never been mesmerized by horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, but I was immediately spellbound by The Night Ocean.”) Could you talk about balancing your often recondite or subcultural interests with writing for a broader audience?

PLF: Part of that comes from writing so many pieces for the Village Voice and the Believer! I was taking on some very esoteric subjects, but writing for a completely non-specialized audience, which, I have to say, was a wonderful change from the academic writing I’d been doing at Stanford. So I had to figure out how to introduce the reader into these very particular worlds, each of which has its own terminology—Volapük has its own entire language!—and its own cast of peculiar and fascinating characters, whose names are totally unknown to the general reading public.

Now that I think of it, the way I introduced that Volapük essay, by writing about a time in the late 90s when I was at a party with my friend Herb, and I met a woman who spoke Volapük, was not unlike how The Night Ocean begins: a party, a chance meeting, the start of a relationship. Which was a way to pull the reader into this new, strange world.

EP: I remember talking to you several years back—you must have been in the middle of your Cullman research fellowship at the New York Public Library, diving into the letters of H.P. Lovecraft and the lives of some of the writers he intersected with. My memory is that you were contemplating a nonfiction book about these people. Do you remember when you realized it had to be a novel?

PLF: The historical material that shows up in The Night Ocean is so rich that I still think it would make a great work of nonfiction, but it would have to be written by someone even more obsessive than I am. There’s just too much material, not only about Lovecraft, but about his friends and protégés, some of whom became great writers and editors in their own right and who inhabited all these different worlds. Lovecraft knew Hart Crane, and he once went to a party in the apartment on Columbia Heights where Crane had written “The Bridge,” which was actually the building where Washington Roebling lived when he was building the Brooklyn Bridge—how much would you have to know, about weird fiction and 20th-century poetry (and architecture, too), to make that one scene come to life?

Then there’s Robert Barlow, the central historical figure in The Night Ocean. His life spans the worlds of weird fiction, experimental poetry in mid-20th century San Francisco, and Mexican anthropology and archeology, in English, Spanish, and Nahuatl. Barlow did so much in his short life—he died at 32—that he’s almost impossible to write about. Nine people have tried to write his biography, and none of them have succeeded.

Which isn’t to say that I wrote The Night Ocean as a novel out of sheer laziness. I knew from the beginning of the project that it would be about hoaxes and deceptions, among other things; some of the stories in it would be true but some of them would not, and the action of the novel would involve sorting the one kind of story from the other, to the extent that one ever can do that.

I spent about a year researching The Night Ocean, and I put a lot of what I learned into the book but far from all of it. I still have hundreds of pages of notes about people who I couldn’t find room for. There’s Hart Crane and Washington Roebling and an episode about the British fantasy writer and artist Mervyn Peake (the of Titus Groan, etc.), and how his life was changed by his visit to the Belsen concentration camp just after the end of the Second World War in Europe, which I kept trying to work into my novel and never could. If someone else wants to borrow all those notes for a nonfiction book, they’re welcome to.

The post Paul La Farge and Ed Park: In Praise of the Old School Cold Take appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Bookstore News: March 9, 2017

ABA to provide low-cost e-commerce platform; a feminist bookstore opens in Montreal; a Providence store faces a forced move; and more.

ABA Adding Low-cost E-commerce Alternative: IndieLite is a new platform under development by the American Booksellers Association for bookstores just getting started with online sales or want a simple, low-maintenance option compared with ABA's signature IndieCommerce platform.

Feminist Bookstore Opens in Montreal: After a soft-launch in December, L’Euguélionne is now open for business. The non-profit bookstore is Canada's only feminist bookstore, after the closing of Northern Woman’s Bookstore in Thunder Bay, Ontario last year.

French Bookstore Has Instagram Hit with Hybrid Photos: The Instragram site of Librairie Mollat in Bordeaux, opened in 1896 and said to be the first independent bookstore in France, has gained nearly 20,000 followers in a few days after posting a series of photos blending real customers faces and bodies with book covers.

Providence Bookstore Paper Nautilus Must Move: The bookstore has been in the same location for 21 years, but will not have its lease renewed and must move by April 15. A Change.org petition has been launched to change the landlord's mind.

Detroit Bookseller Says Crime is Still Plaguing the City: John K. King, who lives in an apartment above his eponymous bookstore, says that crime continues to push people out of the city of Detroit and the answer is to bring more immigrants to live in the city.

The post Bookstore News: March 9, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

BookExpo Editors’ Buzz Finalists Announced

BookExpo has named its finalists for its Editors’ Buzz program, which highlights titles in three categories expected to resonate with readers in 2017.

The books will be touted at panel presentations, where the books' editors will discuss the work. The authors with books on the buzz panels will also appear on the BookExpo Authors Stage. Books were selected by three separate committees made up of booksellers, librarians, and other industry professionals.

The program has, in the past, selected nine books that proved to be bestsellers, according to BookExpo.

The finalists in each category are as follows:

For adult:

Unraveling Oliver by Liz Nugent

Scout Press

Publication Date: August 22, 2017

Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo

Alfred A. Knopf

Publication Date: August 22, 2017

My Absolute Darling by Gabriel Tallent

Riverhead Books

Publication Date: August 29, 2017

The World of Tomorrow by Brendan Mathews

Little Brown and Company

Publication Date: September 5, 2017

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin

Putnam

Publication Date: January 9, 2018

The Woman in the Window by A.J. Finn

William Morrow

Publication Date: January 23, 2018

For young adult:

Spinning by Tillie Walden

First Second Books

Publication Date: September 12, 2017

Beasts Made of Night by Tochi Onyebuchi

Razorbill

Publication Date: September 12, 2017

All the Wind in the World by Samantha Mabry

Algonquin Books for Young Readers

Publication Date: October 10, 2017

The 57 Bus: A True Story of Two Teenagers and the Crime That Changed Their Lives by Dashka Slater

Farrar Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers

Publication Date: October 17, 2017

Dear Martin by Nic Stone

Crown Books For Young Readers

Publication Date: October 17, 2017

For middle grade:

Auma's Long Run by Eucabeth Odhiambo

Carolrhoda Books

Publication Date: September 1, 2017

The Witch Boy by Molly Ostertag

Graphix

Publication Date: September 1, 2017

Greetings From Witness Protection! by Jake Burt

Feiwel & Friends

Publication Date: October 3, 2017

The Stars Beneath Our Feet by David Barclay Moore

Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers

Publication Date: October 24, 2017

The Unicorn Quest: The Whisper in the Stone by Kamilla Benko

Bloomsbury Children's Books

Publication Date: January 30, 2018

The post BookExpo Editors’ Buzz Finalists Announced appeared first on Art of Conversation.