Roy Miller's Blog, page 208

April 25, 2017

C2E2 Attendance Grows, But Graphic Novel Sales Fall

This content was originally published by on 1 January 1970 | 12:00 am.

Source link

Comics sales figures are stagnant, but the mood among retailers remains upbeat. That was the paradoxical takeaway from the Diamond Retailer Summit, a gathering of comics retailers held during the Chicago Comics Entertainment Expo or C2E2, which took place April 19-23 at McCormack Place in Chicago.

C2E2 had its biggest single day ever on Saturday, when fans lined up for a joint appearance by mythic comics figures Stan Lee and Frank Miller, their first convention team-up. Initial numbers show attendance of 80,000 fans, up from 72,000 in 2016, according to Mike Armstrong, event and sales director at show organizer ReedPOP.

At the Diamond Retail Summit breakfast presentation for comics specialty retailers, results for the first quarter of 2017 were mixed, with comics periodicals up 0.7% in dollars but graphic novels down 10.7% from 2016. When toys are factored in, Diamond’s sales are down 3.5% for the year. Customer count--the number of new stores being opened--was flat.

Unit sales are up, but mostly because of free overships (comics publishers sometimes add free bonus copies to a retailer’s order) by Marvel and DC. Also boosting the sales numbers is the continued use of variant covers (offering multiple covers done by high profile artists for certain issues).

The drop in graphic novel sales wasn’t explained, but may be at least partly due to the strong 2016. Last year's high points included Alan Moore's The Killing Joke, a perrennial backlist bestseller, and various Image titles.

Both Marvel and DC announced new programs. DC revealed Dark Matter, a line that will introduce new characters into the DC universe, executed by top level talent. Meanwhile, Marvel is looking to shore up its flagging sales with Legacy, a storyline that will bring back an emphasis on the brand's most iconic characters.

Dark Matter, announced at a high energy presentation by DC co-publishers Dan DiDio and Jim Lee, will see six periodicals roll out. The forthcoming titles include The Silencer by Dan Abnett and artist John Romita Jr., and Immortal Men, by James Tynion IV with art by Jim Lee. At a press event Romita, whose father, John Romita Sr. was an iconic Marvel artist, pushed back against comments in the media about the importance of comics writers over artists. “People have the impression that writers are the gods of this process. They are not,” Romita said.

DC also promoted the idea of diversity both on the page and behind it– although the optics of the press conference, with four white men and Lee (who is of Korean descent), somewhat played against that idea. Lee acknowledged it wasn’t the most “woke” look, but attributed the lack of diversity on the stage to scheduling difficulties.

Marvel’s rebranding is even more of an uphill climb after a widely unpopular linewide crossover event called Secret Empire that has polarized readers. After a multi-year stretch where their major characters were replaced by new ethnically and gender diverse versions--a black Miles Morales as Spider-Man and a female Thor, for instance--the Legacy initiative will return the regular white male versions of these heroes to their titles. It does so, however, after they team up with their replacements in a series of one shot periodicals called “Generations.”

Despite the changes at the Big Two, retailers were generally upbeat about the industry. They cited the increase in graphic novels for kids, and a variety of content options from independent publishers including Image, Valiant, Dynamite, IDW and Boom!, as well as new publishers such as AfterShock and Lion Forge, which will debut of its Catalyst line of superhero comics, and Cubhouse comics for young readers.

As for the show itself, which made a number of improvements over last year's show, including the expansion of Artist Alley (a section devoted to tables by individual artists), the jury is still out on whether C2E2 will become a “must do show.”

Mitigating factors include a crowded spring schedule that features such shows as Emerald City Comic Con (also run by ReedPOP), the well-established WonderCon and now Fan Expo Dallas. All three shows are held in March and April.

Still, this year’s event had the air of a special moment. Citing the huge crowd on Saturday, Armstrong said: "It felt a little like New York Comic Con the year when it broke out and we thought ‘ Man, we really have something here.’"

The post C2E2 Attendance Grows, But Graphic Novel Sales Fall appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Watching Their Dust: Photographing Players in Pollination

This content was originally published by RACHEL NUWER on 24 April 2017 | 8:26 pm.

Source link

Spend just a few minutes in a garden this time of year, and you will likely see a pollinator buzzing or fluttering from flower to flower. While most of us are aware of this vitally important ecosystem service, the act itself — the transfer of pollen from stamen to stigma via tiny feet, wings, antennas or mouthparts — is largely unseen.

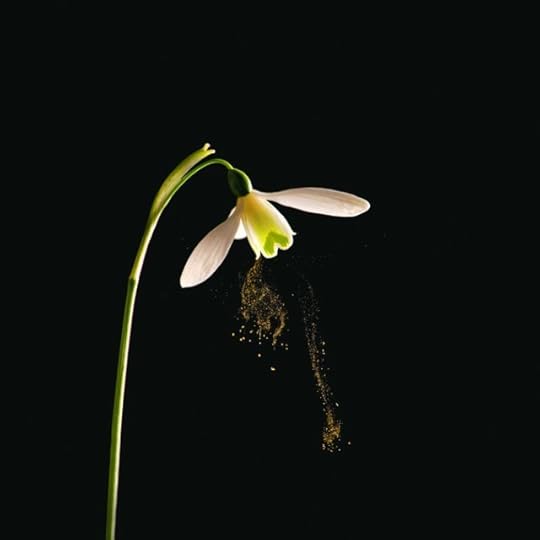

In “Pollination Power,” Heather Angel, a photographer based in Surrey, England, exposes the process in macrophotography, which stands out not only for its range and aesthetics, but also for its scientific exactness: She was determined to show not just creatures in flowers, but the instant release of pollen itself.

Photo

Credit

Heather Angel

Photo

Topside view of a spider flower, top, and a photomicrograph of the planktonic freshwater alga Volvox.

Topside view of a spider flower, top, and a photomicrograph of the planktonic freshwater alga Volvox.Credit

Heather Angel

Ms. Angel’s pursuits took her to 20 countries, from Kazakhstan to Costa Rica, though some of her most productive trips were closer to home: to her own backyard and to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, in London.

The diversity of plants she captured is equaled only by the diversity of pollinators. “Bees get all the publicity, but there are so many other insects and animals that are important pollinators,” she said. While her photographs include bees and butterflies galore, they also spotlight more unlikely players: hoverflies, scarab beetles, day geckos and blue tits.

Technical expertise made many of the images possible. Ms. Angel used an ultraviolet flash to expose the brilliant petal patterns and fluorescing nectar that many flowers produce for the benefit of their pollinators, normally invisible to the human eye. A red light allowed her to photograph nocturnal moth pollinators.

Photo

Credit

Heather Angel

Photo

Mechanical vibration of a snowdrop, top, and a honeybee on the open bud of an evening primrose.

Mechanical vibration of a snowdrop, top, and a honeybee on the open bud of an evening primrose.Credit

Heather Angel

Plants are not passive players in pollination, and Ms. Angel paid special attention to their role in taking care of business.

Some flowers change color when pollination is complete, signaling to would-be visitors that they should move on to freshly opened blooms. Others open and close to control the timing of the act. All provide some form of enticement for pollinators: sugary nectar, pollen, a place to find a mate or even shelter from the elements.

Photo

Credit

Heather Angel

Photo

A high-speed flash freezes the pollen release from the anther pores of a Chilean bellflower, above, and a male hazel catkins releases its pollen clouds from leafless branches. The tiny red structure on the same branch is the erect female flower, which is wind pollinated.

A high-speed flash freezes the pollen release from the anther pores of a Chilean bellflower, above, and a male hazel catkins releases its pollen clouds from leafless branches. The tiny red structure on the same branch is the erect female flower, which is wind pollinated.Credit

Heather Angel

“Sometimes you see up to five solitary male bees sleeping in a flower,” Ms. Angel said.

Continue reading the main story

The post Watching Their Dust: Photographing Players in Pollination appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Paula Hawkins’s ‘Into the Water’ Dives Into Murky Skulduggery

This content was originally published by JANET MASLIN on 24 April 2017 | 10:00 pm.

Source link

What happened to the Paula Hawkins who structured “The Girl on the Train” so ingeniously? That book, and the ensuing movie starring Emily Blunt, used a cleverly devised unreliable narrator, focused on interrelated couples, revealed all its characters to be untrustworthy and came close to bursting at its seams. But that story radiated sheer serenity compared with the three-ring circus that “Into the Water” becomes.

The new one properly begins in 2015 with the death of Nel Abbott. (Make a chart. A big one.) Nel was the mother of 15-year-old Lena, whose best friend, Katie Whittaker, died in the water only a few weeks earlier. Nel has a chilly estranged sister, Julia (known as Jules), who’s been gone so long she doesn’t know her niece Lena, but now comes back to town to impose her presence on the orphaned girl. Lena has no idea who her father was. But he must have been a man and therefore likely a terrible monster. Every man in “Into the Water” has the potential to be one.

Louise Whittaker, Katie’s mother, walks the path beside the river daily as she mourns her daughter. Patrick Townsend, the oldest man in the book, is a frequent walker too. There’s more walking here than in the average Jane Austen novel, and not much else to do in Beckford. We do learn that it’s possible to buy milk and a newspaper somewhere, but everyone seems most drawn to the sinister, wet, lethal outskirts of town.

Photo

Paula Hawkins

Credit

Alisa Connan

Patrick is the father of Sean Townsend, a detective assigned to look into Nel’s death. Sean has his own traumatic history involving a drowned Beckford woman, but nobody thinks to bring it up before he’s given the case. Sean’s partner is Erin Morgan, who likes to run on the riverbank and does her best not to wonder what kind of crazy place this is. And Sean is married to but separated from Helen, head of the local school, who knew a lot about Katie and Lena’s friendship. A teacher on Helen’s staff, Mark Henderson, knows all the local teenagers, has had enough of the school system and would dearly love to get out of town.

Finally, and why not, there’s the psychic. Her name is Nickie Sage and she looks and dresses like a goth witch. She knows a lot more than the police do about Beckford’s endless parade of secrets.

Continue reading the main story

Hawkins does not so much introduce these characters as throw them at the reader in rapid succession. There’s no time to process who’s who, and not much detail about any of them. The writing doesn’t help: Nel’s high school boyfriend (not even mentioned above) is “tall, broad and blond, his lips curled into a perpetual sneer.” One detective describes Beckford as “a strange place, full of odd people, with a downright bizarre history.” So much for prose. As for dialogue, Jules actually leans over Nel’s corpse and whispers: “What did you want to tell me?”

Many of us are going to read this novel anyway. Hawkins could have published a book of 386 blank pages and hit the best-seller lists. So on the bright side for those who insist: A few of the book’s many killings happen for unexpectedly powerful reasons. The one that occurs in 1920 delivers a particularly strong shock. And even though Hawkins does a lot of needless obfuscating just to keep her story moving, she blows enough smoke to hide genuinely salient clues. “Clues” isn’t quite the right word, since nobody in this book behaves logically, schemes cagily, has legitimate motives or relies on any sane staples of the murder story.

“Into the Water” chugs off to a slow, perplexing start, but it develops a head of steam at an unlikely moment. It has exactly one smart, perfectly conceived Hitchcockian page: its last.

Continue reading the main story

The post Paula Hawkins’s ‘Into the Water’ Dives Into Murky Skulduggery appeared first on Art of Conversation.

April 24, 2017

Robert M. Pirsig, Author of ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,’ Dies at 88

This content was originally published by PAUL VITELLO on 24 April 2017 | 11:30 pm.

Source link

Todd Gitlin, a sociologist and the author of books about the counterculture, said that “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,” in seeking to reconcile humanism with technological progress, had been perfectly timed for a generation weary of the ’60s revolt against a soulless high-tech world dominated by a corporate and military-industrial order.

Photo

novel remained near the top of the best-seller lists for a decade." data-mediaviewer-credit="William Morrow & Company" itemprop="url" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/.... Pirsig’s dense novel remained near the top of the best-seller lists for a decade.

Credit

William Morrow & Company

“There is such a thing as a zeitgeist, and I believe the book was popular because there were a lot of people who wanted a reconciliation — even if they didn’t know what they were looking for,” Mr. Gitlin said in 2013 in an interview for this obituary. “Pirsig provided a kind of soft landing from the euphoric stratosphere of the late ’60s into the real world of adult life.”

Mr. Pirsig’s plunge into the grand philosophical questions of Western culture remained near the top of the best-seller lists for a decade and helped define the post-hippie 1970s landscape as resoundingly, some critics have said, as Carlos Castaneda’s “The Teachings of Don Juan” helped define the 1960s.

Continue reading the main story

Where “Don Juan” pursued enlightenment in hallucinogenic experience, “Zen” argued for its equal availability in the brain-racking rigors of Reason with a capital R. Years after its publication, it continues to be invoked by famous people when asked to name a book that affected them most deeply — among them the former professional basketball player Phil Jackson, the actors William Shatner and Tim Allen, and the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk, a Nobel laureate.

Part road-trip novel, part treatise, part open letter to a younger generation, “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” unfolds as a fictionalized account of a cross-country motorcycle trip that Mr. Pirsig took in 1968 with his 11-year-old son, Christopher, and two friends.

The narrative alternates between travelogue-like accounts of their 17 days on the road, from the Pirsigs’ home in Minnesota to the Pacific Coast, and long interior monologues that he calls his “Chautauquas,” after the open-air educational meetings at Lake Chautauqua, N.Y., popular with self-improvers since the 19th century.

Mr. Pirsig’s narrator (his barely disguised stand-in) focuses on what he sees as two profound schisms. The first lay in the 1960s culture war, in which the “hippies” rejected industrialization and the technological values that had been embraced by the “straight” mainstream society.

The second schism is in the narrator’s own mind, as he struggles in his hyperrational way to understand his recent mental breakdown. Mr. Pirsig, who was told he had schizophrenia in the early 1960s, said that writing the book was partly an effort to make peace with himself after two years of hospital treatments, including electric shock therapy, and the turmoil that he, his wife and children suffered as a result.

Describing both breakdowns, cultural and personal, Mr. Pirsig’s narrator invokes the Civil War: “Two worlds growingly alienated and hateful toward each other, with everyone wondering if it will always be this way, a house divided against itself.”

He adds: “What I’m trying to do here is put it all together. It’s so big. That’s why I seem to wander sometimes.”

(Mr. Pirsig’s son Chris was later also found to be mentally ill and institutionalized. He died in 1979 after being stabbed in a mugging outside the San Francisco Zen center where he had been living.)

Continue reading the main story

In a foreword to the book, Mr. Pirsig told readers that despite its title, “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” should “in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice.”

He added, “It’s not very factual on motorcycles either.”

Instead, he wrote later: “The motorcycle is mainly a mental phenomenon. People who have never worked with steel have trouble seeing this.”

He added, “A study of the art of motorcycle maintenance is really a miniature study of the art of rationality itself.”

The literary critic George Steiner, writing in The New Yorker, described the book as “a profound, if somewhat clunky, articulation of the postwar American experience” and pronounced it worthy of comparison to “Moby-Dick” as an original American work. The New York Times critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, in his review, threw in a comparison to Thoreau. In London, The Times Literary Supplement called the book “disturbing, deeply moving, full of insights.”

(Not all reviewers were wowed. Writing in Commentary, Eva Hoffman found Mr. Pirsig’s ruminations obtuse. “Beneath the complexity of disorganization,” she said, “the picture of society which the book presents and the panaceas it offers are distressingly naïve.”)

One of Mr. Pirsig’s central ideas is that so-called ordinary experience and so-called transcendent experience are actually one and the same — and that Westerners only imagine them as separate realms because Plato, Aristotle and other early philosophers came to believe that they were.

But Plato and Aristotle were wrong, Mr. Pirsig said. Worse, the mind-body dualism, soldered into Western consciousness by the Greeks, fomented a kind of civil war of the mind — stripping rationality of its spiritual underpinnings and spirituality of its reason, and casting each into false conflict with the other.

In his part gnomic, part mechanic’s style, Mr. Pirsig’s narrator declares that the real world is a seamless continuum of the material and metaphysical.

“The Buddha, the Godhead,” he writes, “resides quite as comfortably in the circuits of a digital computer or the gears of a cycle transmission as he does at the top of a mountain or in the petals of a flower.”

Continue reading the main story

Robert Maynard Pirsig was born in Minneapolis on Sept. 6, 1928, to Harriet and Maynard Pirsig. His father was a law professor and dean of the University of Minnesota Law School. As a child, Robert spoke with a stammer and had trouble making friends; though highly intelligent (his I.Q. was said to be 170), he was expelled from the University of Minnesota because of failing grades.

Serving in the Army before the start of the Korean War, he visited Japan on a leave and became interested in Zen Buddhism, and remained an adherent throughout his life. After his Army service, he returned to the university and received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in journalism.

He later studied philosophy at the University of Chicago and at Banaras Hindu University in India and taught writing at Montana State University in Bozeman and the University of Illinois at Chicago. He also did freelance writing and editing for corporate publications and technical magazines, including the first generation of computer journals.

His first marriage, to Nancy Ann James, ended in divorce. He married Wendy Kimball in 1978. She survives him, as do a son, Ted; a daughter, Nell Peiken; and three grandchildren.

Mr. Pirsig maintained that 121 publishing houses rejected “Zen” before William Morrow accepted it. He was granted a $3,000 advance, but an editor cautioned him against hoping the book would earn a penny more. Within months of its release, it had sold 50,000 copies.

With the book’s success Mr. Pirsig became famous, wealthy and the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship. He also, he said, became thoroughly unnerved. After enduring a flood of interviews, he began refusing them. He said he had reached the limits of his patience when fans started showing up at his house outside Minneapolis.

His neighbors called them “Pirsig’s Pilgrims.” Most were young people in search of a guru. Mr. Pirsig wanted none of it.

“One morning I just woke up at 3,” he told The Washington Post years later. “I told my wife, ‘I just have to get out of here.’ We had the camper packed in half an hour, and I was on the road.” He stayed away for months at a time, sometimes far out at sea on his boat.

Continue reading the main story

In interviews, he lamented that he was not embraced by academic philosophy departments, and that his books were sometimes lumped with “new age” publications in bookstores.

The near-cult popularity of “Zen,” though, puzzled him for years before he came up with a theory. Writing in an afterword to the 10th-anniversary edition in 1984, he used a Swedish word (it was his mother’s native language) to describe the phenomenon. “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,” he wrote, was a “kulturbarer,” or culture-bearer.

A culture-bearing book is not necessarily a great book, he said. It does not change the culture. It simply heralds a change already underway. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” an indictment of slavery published before the Civil War, was a culture-bearing book, he said.

“I was just telling my own story,” he said in a short interview posted on his website. He had never intended to make a splash.

“I expressed what I thought were my prime thoughts,” he added, “and they turned out to be the prime thoughts of everybody else.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Robert M. Pirsig, Author of ‘Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,’ Dies at 88 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

The Key to Creating Great Characters

This content was originally published by Guest Column on 24 April 2017 | 4:00 pm.

Source link

Among the great strokes of good fortune — and there were many junctures where I could have gone awry — was the decision to write about, via fiction, my small marina family at Tarpon Bay, Sanibel Island, Florida, where I was a fishing guide from 1974 to 1987. This marina family embraced a wider tribe of watermen from along the Gulf Coast, fascinating characters, and also decent, caring people, who now populate my novels.

First, the protagonist: I was an experienced fishing guide, so why not a marine biologist? Also, thanks to Outside Magazine, I’d traveled countries torn by wars and revolutions, so why not a biologist who was also a clandestine operator – a “spook” with skills and knowledge far beyond my own?

I liked the potential such a character offered. Marion D. Ford struck me as a good, solid name.

This guest post is by Randy Wayne White. White’s latest release is Mangrove Lightning: A Doc Ford Novel. He is the author of the Doc Ford novels and the Hannah Smith novels, and four collections of nonfiction. He lives on Sanibel Island, Florida, where he was a light-tackle fishing guide for many years, and spends much of his free time windsurfing, playing baseball, and hanging out at Doc Ford’s Rum Bar & Grille. For more information, please visit randywaynewhite.com and follow the author on Facebook.

This guest post is by Randy Wayne White. White’s latest release is Mangrove Lightning: A Doc Ford Novel. He is the author of the Doc Ford novels and the Hannah Smith novels, and four collections of nonfiction. He lives on Sanibel Island, Florida, where he was a light-tackle fishing guide for many years, and spends much of his free time windsurfing, playing baseball, and hanging out at Doc Ford’s Rum Bar & Grille. For more information, please visit randywaynewhite.com and follow the author on Facebook.

As my editor at Putnam’s, Neil Nyren, has said more than once, a series must be populated with characters that readers want to spend their private time with. As a likeable character, I settled on a hipster boat bum, Tomlinson. But he had to have more than stoner’s sensibilities to appeal to a tough pragmatist like Doc Ford. So, I decided these two would be, cerebrally speaking, polar opposites, and thus attracted as physics demands. Ford, purely linear, unsympathetic. Tomlinson, a purely spiritual, empathetic creature who also loved to womanize and smoke grass. I envisioned the beginning of a sort of spiritual death dance, which made sense to me, anyway, because those two cerebral qualities – the wistful, spiritual; the cold eyed pragmatist – are always at odds, battling for supremacy in my head. (Ask yourself this: in you, which of those qualities most often wins out?) Fun stuff. . . except for the numbing hard work that good writing requires.

The deep affection I feel for Doc Ford and Tomlinson has roots in family, but more so in my treasured friends. As Marion Ford has opined in more than one book: “Friendship has more to do with alchemy than chemistry. It is a bond that comes with obligations, loyalty first among them.” Another Ford quote that I embrace as a credo is: “I admire the small, brave unknown people; people who forge ahead positively, productively despite the inevitable disappointments, illnesses and occasional tragedies that befall us all. They don’t make the headlines, but they are the sinew of our social fabric.”

[]

It’s true that the deep affection I feel for Hannah Smith is also rooted in family stories, and the music of Southern voices. My mother and her sisters were not only natural born rebels (and feminists), they were (and are) hilarious. If Hannah’s voice has a lyrical, authentic ring, the credit goes to the Wilson sisters of Hamlet and Rockingham, North Carolina.

Hannah is a strong, independent woman, and I have always been drawn to women who, rather than being content to serve as their husbands’ orbiting stars, strike out on their own, convention be damned, and pursue their own lives and destinies. As evidenced in my Doc Ford novels (I hope), I am also fascinated by women who aren’t physically attractive by Hollywood standards yet who are imminently attractive to me and other men by virtue of their energy, confidence and their determination to live big lives.

Before I start a book, I write lengthy bios of all main characters — bios that include information my readers will probably never see. It’s the tip-of-the-iceberg approach. If the writer portrays the tip clearly, honestly, the mountain below is believable, even though implied. If I know my characters intimately, they come to life and remain true to themselves from page one, and even beyond where a book ends. Hannah, Nate, Hannah’s mother, Loretta, and the rest will find their own paths. It is up to me to follow them loyally.

This special value pack is filled with 2016 Writer’s Digest Conference sessions,

This special value pack is filled with 2016 Writer’s Digest Conference sessions,

including how to write, pitch, publish, and market your book.

Get 12 conference sessions for one low price right here.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

Brian A. Klems is the editor of this blog, online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

Listen to Brian on: The Writer’s Market Podcast

You might also like:

The post The Key to Creating Great Characters appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Sheryl Sandberg Finds Comfort for Herself and Offers It to Others

This content was originally published by CAITLIN FLANAGAN on 23 April 2017 | 3:24 pm.

Source link

Photo

OPTION B

Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy

By Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant

226 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $25.95.

You could almost hear the collective gasp when news broke, in May 2015, that the internet entrepreneur Dave Goldberg had died suddenly while on vacation in Mexico with his wife, Sheryl Sandberg. Their marriage had become a public one ever since the publication, two years earlier, of “Lean In,” her book about women and leadership. In it she had written some revolutionary things about marriage (she called it having a “partner,” but the book was so much about redefining gender roles that she clearly seemed to be talking about husbands). Deciding to get married — and the choice of whom to marry — weren’t just central to one’s private life, she wrote. Together they made up the “most important career decision that a woman makes.” She observed that most women at the top aren’t the lonely, single women of clichés; they are married women whose husbands support their ambitions and take equal responsibility for making a home. She said that her great success (she is the chief operating officer of Facebook, which has made her a billionaire) would have been impossible without the unwavering support of her husband. Now, in the cruelest way, she had lost him.

“Lean In” sparked a movement, but it had its critics, among them single mothers, women who worked outside corporate America, and those who could not afford to hire the nannies and helpers upon whom the Sandberg-Goldberg household clearly depended. There were also those who thought the principal value underlying the book was flawed. They didn’t want to find ways to make their work more exhilarating; they wanted to find ways to accommodate it to their lives as parents. The tragedy was a vicious reminder of the truth we work hard to forget: Life is cruel. It will casually take away the people we love the most. Even the vaunted “C-suite” job is cold comfort when it cost you hours with a lost loved one. Now, two years after Goldberg’s death, Sandberg has written a new book, “Option B,” which forthrightly addresses all of these issues. It is a remarkable achievement: generous, honest, almost unbearably poignant. It reveals an aspect of Sandberg’s character that “Lean In” had suggested but — because of the elitism at its center — did not fully demonstrate: her impulse to be helpful. She has little to gain by sharing, in excruciating detail, the events of her life over the past two years. This is a book that will be quietly passed from hand to hand, and it will surely offer great comfort to its intended readers.

“I have terrible news,” she told her children, after flying home from Mexico. “Daddy died.” The intimacy of detail that fills the book is unsettling; there were times I felt that I had come across someone’s secret knowledge, that I shouldn’t have been in possession of something that seemed so deeply private. But the candor and simplicity with which she shares all of it — including her children’s falling to the ground, unable to walk to the grave when they arrive at the cemetery — is a kind of gift. She was shielded from the financial disaster that often accompanies sudden widowhood, but in every other way she was unprotected from great pain.

As she did in the memorable Facebook post composed a month after the death, she reports turning in her misery to the psychologist Adam Grant, a friend who had flown to California to attend the funeral and is an expert in the field of human resilience. She told him that her greatest fear was that her children would never be happy again. He “walked me through the data,” she writes, and what she learns offers comfort. Getting “walked through the data,” is as modern a response to grief as the notion that “resilience” is some kind of science. The book includes several illustrative stories that seem to come from Grant’s research, but they are not memorable. It is Sandberg whose story commands our riveted attention, and it is her natural and untutored responses to the horror that are most moving. “This is the second worst moment of our lives,” she tells her sobbing children at the cemetery. “We lived through the first and we will live through this. It can only get better from here.” That is grief: Somehow, you find a language; somehow you get through it. No research could have helped her in that moment. She is the one who knew what to do and what to say. They were her children, and she knew how to comfort them.

Death humbles each of us in different ways. Suddenly a single mother, Sandberg realized how hollow her “Lean In” chapter about the importance of fully involved husbands (“partners”) must have been to unmarried women. If only she had known how little time she would have with her husband, she thinks, she would have spent more of it with him. But that’s not the way life works; Dave Goldberg fell in love with a woman who wanted to lead, not one who wanted to wait for him to come home from the office. The unbearable clarity that follows a death blessedly fades with time. We couldn’t live with it every day.

Sheryl Sandberg followed the oldest data set in the world, the one that says: The children are young, and you must keep going. Slowly the fog began to lift. She found she had something useful to offer at a meeting; she got the children through their first birthdays without their father; she began to have one O.K. day and then another. She made it through a year, all of the “milestone days” had passed and something began to revive within her. Grief is the final act of love, and recovery from it is the necessary betrayal on which the future depends. There is only this one life, and we are the ones who are here to live it.

Continue reading the main story

The post Sheryl Sandberg Finds Comfort for Herself and Offers It to Others appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Free Books Giveaway!

I'm running a contest for some free books! This giveaway begins Tuesday, April 25th at 12:00 AM and will continue until Tuesday, May 2nd at 12:00 AM. At the end of the week-long signup window the winner will be chosen at random and they will receive:

Single, signed copies of all three of my currently published books.

Printed manuscript of an unreleased story from my early days.

A few business cards and a luxury postcard featuring my first publication.

A donation to The Dougy Center in your name, with a printed receipt.

Assorted goodies.

Of course, as with any contest that provides physical prizes, you must be able and willing to provide a valid shipping address to receive the winnings. Unfortunately, this first contest will only be open to those in the continental US, but I'm hoping to make the next one international. Subscribe to the mailing list to unlock the entry form below!

The post Free Books Giveaway! appeared first on Art of Conversation.

A publisher of one’s own: Virginia and Leonard Woolf and the Hogarth Press | Books

This content was originally published by Rafia Zakaria on 24 April 2017 | 2:15 pm.

Source link

“We unpacked it with enormous excitement, finally with Nelly’s help carried it into the drawing room, set it on its stand, and discovered that it was smashed in half,” wrote Virginia Woolf on the afternoon of 24 April 1917. That day she and her husband Leonard took delivery of the hand press that heralded the birth of their brainchild, the Hogarth Press. Their £19 purchase had been long awaited, one of three resolutions made while the couple took tea on Virginia’s 33rd birthday: they would buy Hogarth House in Richmond, find a hand press to do their own printing, and buy a bulldog and name him John.

The missing part needed to fix the press and render it operative arrived several weeks later and the first publication notice, painstakingly hand set by the Woolfs, was sent out in May. In tidy lettering, it bravely announced the imminent publication of a pamphlet titled Two Stories: one each by Virginia and Leonard.

The Woolfs, photographed in 1914. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

So the Hogarth Press was born, and like all parents the Woolfs declared their lives changed forever. The publishing business that the two set up in their drawing room and which would eventually to take up their dining room, then much of their lives, was supposed to be an answer to so much. It was a physically engrossing activity to ease Virginia’s crippling anxiety, a business that could potentially free the couple from the whims of publishers and even a social outlet through which their diverse literary friendships could be monetised.

It almost lived up to all these weighty expectations. Those first afternoons, when Leonard and Virginia sat covered in ink in the drawing room of Hogarth House, learning by trial and error just how hard it was to set type and centre it on the page, were charmed ones. The experience was a simulacrum of the creative process: the beloved final product did not always reflect the pains of its production.But the labours of printing always delivered the satisfaction of a real and tangible object.

The press also fulfilled a desire for creative freedom that both Leonard and Virginia had craved. Virginia had long resented relying on her half-brother Gerald Duckworth to be her publisher. He was a man who, in her words, could not tell “a book from a beehive” and had no interest in avant garde writing. (Woolf would also later accuse him of molesting her when she was a child.) The acute anxiety she felt when waiting for answers from publishers was partially eliminated by Hogarth. Leonard, while happy to have cut out the middle-man, also revelled in the new venture, declaring in a letter: “I should never do anything else, you cannot think how exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying it is.”

Virginia's lover Vita Sackville-West demanded more money from the Woolfs... she got the money, but lost Virginia

He was right. Leonard’s commitment to the press would be lifelong, carrying on through the interwar period and then the second world war and even after Virginia’s tragic death. What started as a hobby would become a vocation and, in later years, his sole source of income. If Leonard’s involvement was steady, Virginia’s was mercurial, waxing and waning through her depressive and creative spells. As early as March 1924, as they got ready to publish her novel Jacob’s Room, she declared in a letter that “publishing one’s own books is very nervous work”. By October 1933, when Hogarth Press turned 16, Virginia declared herself tired of the “drudgery and sweating” and the “altered travel plans” that running the publisher required. She demanded that an “intelligent youth” be found to take over its day-to-day operations.

[image error]

Leonard Woolf, pictured reading with the poet John Lehmann, who was managing director of the Hogarth Press between 1938 - 1946. Photograph: Hulton Deutsch/Corbis via Getty Images

No youth was found but the press plodded along, continuing its early practice of converting friends into Hogarth authors. This too was laden with complication, at least for Virginia. The second book that Hogarth published was Katherine Mansfield’s Prelude, the production of which caused tension in their friendship. In 1934, Virginia would declare her affair with Vita Sackville-West over because of her intense dislike of the latter’s new novel The Dark Island. The book was still published by Hogarth, but only after protracted and awkward negotiations in which an embarrassed Sackville-West demanded more money from the Woolfs, who had chosen to ignore her previous hints towards a more lucrative contract. She got the money, but she lost Virginia. The whole episode was a fitting indictment of the inevitable acridity of lover-publisher unions.

The Hogarth Press ran until 1946 and, in 29 years, published 527 titles. Precisely a century on, the house is one of many imprints making up thegiant publisher Penguin Random House. That Hogarth has reached this milestone is a considerable achievement; as JH Willis writes in his book on the press, many small presses were birthed in the interwar period – and most perished. But beyond the obvious victory of its survival, the Hogarth story reveals much about publishing and the transformations wrought when writers change sides in the game of literary creation.

Virginia and Leonard both discovered that the limitations of publishers, their one-time oppressors, were now their own. In one striking instance, very early in the life of the press, the Woolfs wrote to James Joyce to reject his manuscript of Ulysses. It was too long and beyond their fledgling capabilities, the Woolfs declared in their letter. It was just the sort of statement they would have resented and mistrusted as writers. But they were publishers, now - and so they made it anyway.

The post A publisher of one’s own: Virginia and Leonard Woolf and the Hogarth Press | Books appeared first on Art of Conversation.

In Praise of Derek Walcott’s Epic of the Americas

This content was originally published by JULIAN LUCAS on 23 April 2017 | 9:45 pm.

Source link

The last place “Omeros” took me was to St. Lucia, where just over a year before Walcott died I attended the Nobel Laureate Week celebrations for his 86th birthday. During a catamaran ride around the island, while dozens of guests danced and drank on deck, the poet sat anchored in his wheelchair like Odysseus tied to the mast. His eyes read the passing landscape like a poem in progress: checking the scansion of the shoreline, firming the mountains’ metaphors, making sure there was nothing he had missed.

A Walcott Starter Kit

Photo

If you want to explore Walcott’s poetry, these five works are a good place to begin.

‘MIDSUMMER I ’ (‘MIDSUMMER,’ 1984)

Begin with this window-seat epiphany from the poet in flight, sky liner notes rivaled only by James Merrill’s “A Downward Look” and Elizabeth Bishop’s “Night City.” Walcott approaches Trinidad in a plane recast as a pond’s gliding insect: “The jet like a silverfish bores through volumes of cloud.” From this altitude, all his major themes appear in dioramic miniature: the Odyssean homecoming, this contiguity between language and landscape (“sharp exclamations of whitewashed minarets”), and the Caribbean’s existence beyond official histories. Landing is loveliest — each successive layer of the rematerializing world yields a “shelving sense of home.”

Continue reading the main story

‘ THE SEA IS HISTORY ’ (‘THE STAR- APPLE KINGDOM, 1979)

The orator Demosthenes liked to practice speaking on the seashore, voice raised in challenge to the roaring surf. The ocean is an ancient argument, and here Walcott makes it answer a contemptuous dismissal of the islands’ history. “Where are your battles, your monuments, martyrs?” asks the voice of a metropolitan skeptic — and the poet’s strident answer is “the sea.” Underwater, Caribbean pasts fuse with biblical scenes and the rhythms of marine life, evoking both classical underworlds and the sunken island afterlife of Haitian Voodoo. Bones from the drowned of the Middle Passage are reborn as a living Book of Exodus: “mosaics/ mantled by the benediction of the shark’s shadow.”

‘ LOVE AFTER LOVE ’ (‘SEA GRAPES,’ 1976)

If Walcott had a pop song, “Love After Love” would be it. Uncharacteristically free of proper nouns (no Latinate tropical flowers or seaside villages with soft Creole names), it is a simple, tender promise of healing after heartbreak:

The time will come

when, with elation

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror.

A celebration of return from love’s tempestuous self-exile, the poem’s interior landfall is ultimately inseparable from Walcott’s grander voyages. Concentrically nested in all his circumnavigations of history are the wanderings and homecomings of the individual heart.

‘ THE ANTILLES: FRAGMENTS OF EPIC MEMORY’ (1992)

Evoking a Trinidadian performance of the Hindu epic “The Ramayana,” Walcott begins his 1992 Nobel Lecture by celebrating the hybrid beauty of Caribbean civilization. The speech is not only a paean to a region but a defense of the islands often dismissed (even by V. S. Naipaul, Walcott’s nemesis) as shapeless derivations of those African, Asian and European “originals” from which its people retain only shards. But it is in this “gathering of broken pieces” that Walcott finds the archipelago’s poetry: “Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.”

‘ANOTHER LIFE’ (1973)

Rare is the artist lucky enough to grow up with his country. “For no one had yet written of this landscape/ that it was possible,” says Walcott in this luminous autobiography, a verse chronicle of his artistic apprenticeship during the twilight of colonialism and the early years of St. Lucia’s independence. The book’s highlight is Walcott’s young friendship with the painter Dunstan St. Omer (Gregorias in the poem), companion and competitor in his quest to immortalize the island. Among the most moving tributes to home in poetry, “Another Life” makes it clear why St. Lucia gave Derek Walcott a state funeral — his coffin swathed in the national flag designed by St. Omer.

Continue reading the main story

The post In Praise of Derek Walcott’s Epic of the Americas appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Bookstore News: April 24, 2017

This content was originally published by on 1 January 1970 | 12:00 am.

Source link

Toronto gets a new indie; funding campaign launches for new Bay Area bookstore; Books & Brews opens fourth outlet in Indiana; R.J. Julia's hiring criticized; and more.

Source link

The post Bookstore News: April 24, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.