Roy Miller's Blog, page 204

April 29, 2017

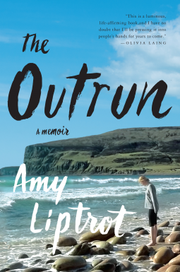

Finding Sobriety in the Rural Rituals of Her Remote Orkney Home

This content was originally published by DOMENICA RUTA on 28 April 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Photo

Credit

Lisk Feng

THE OUTRUN

By Amy Liptrot

280 pp. W. W. Norton & Company. $25.95.

Amy Liptrot begins her memoir with a glossary: In the Orkney Islands of far northern Scotland, seals are called selkies; cattle are kye; and the fog rolling in from the sea goes by the evocative haar. The place Liptrot uneasily calls home is an enchanted, windswept, salt-scoured archipelago where the northern lights are known as Merry Dancers and “lambing” is both a season and a verb.

The term most central to Liptrot and this gorgeous debut, its guiding symbol and title, is “the outrun,” a stretch of uncultivated hillside land at “the furthest reaches of a farm, only semi-tamed, where domestic and wild animals coexist and humans don’t often visit so spirit people are free to roam.” It is in these wild pastures where Liptrot and her brother grew up with their bipolar father and very religious mother on their family sheep farm. Eager to leave at age 18, Liptrot spent the next decade in London, the antithesis of her bucolic home in the north, transforming herself into a party girl of the Hackney district, a place where “it felt like the perpetual last day of a festival.”

It is exactly the excitement she sought when leaving Orkney, but inevitably the party ceases to be fun. As friends and confederates grow up and drink less, Liptrot sinks deeper into alcoholic isolation. She loses all the typical things: friends, boyfriends, apartments, jobs. Soon all decisions (or lack thereof) flow from one primary purpose: getting drunk. One night she is attacked after hitching a ride with a violent stranger, and narrowly escapes, a brush with trauma that a lesser writer would exploit for dramatic effect. Instead, Liptrot makes a realistic, anticlimactic but ultimately braver and more honest narrative decision to reveal her Turning Point as an emotional threshold — she just couldn’t take the pain of drinking any longer and enrolls herself in rehab.

More than 10 years after fleeing, Liptrot returns to the Orkney Islands, chronicling the first two years of her sobriety in this recovery memoir closer in spirit to the work of the naturalist Rick Bass than the hard-drinking tales of Caroline Knapp or Augusten Burroughs. Full of lucid self-discovery and shimmering prose, “The Outrun” is more atmospheric than it is dramatic. “My life was rough and windy and tangled. Growing up in the wind leaves you strong, sloped and adept at seeking shelter.” Building drystone walls becomes a lesson in patience; delivering newborn lambs brings a sense of renewal. Metaphors lay things bare with a stunning simplicity as Liptrot searches for answers again and again in her island landscape, all sky and sea, where not even language has the ability to conceal.

Photo

She does not flee to her parents, somewhat peacefully divorced now and still living on the main island of Orkney. There is a general restraint when writing about her family, vague specters swept away by the much more formative powers of the ocean and wind. What ultimately heals Liptrot and sustains this patiently wrought memoir are the rough and magical islands of Orkney. She gets a job surveying bird populations, eventually spending the winter on one of the smallest islands, Papay, population 70, where her gaze oscillates between her slow, incremental awakening to the sober world and the breathtaking ecology of her home.

“The Outrun” becomes a kind of personal travelogue of the Orkney Islands, their numinous geology and mystical history, from the unique perspective of one who is both an outsider and a native. One imagines Liptrot writing these pages in the spectacular solitude she finds there, writing as much to stave off loneliness as to mine its many gifts, just as alcohol was once both the problem and the solution. It is a hard battle, and the push and pull, the urge to stay and to go, like the wind and the waves, never stops.

Continue reading the main story

The post Finding Sobriety in the Rural Rituals of Her Remote Orkney Home appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Book Deals: Week of May 1, 2017

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Bloomsbury lands an O. Henry winner; actress Adriana Mather inks a six-figure YA deal; Berkley invests in an Irish journalist; and more in this week's notable book deals.

Source link

The post Book Deals: Week of May 1, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Elizabeth Warren Really Does Not Like Donald Trump

This content was originally published by GREGORY COWLES on 28 April 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Photo

Elizabeth Warren

HER BACK PAGES: You can tell a lot about a book from its index. Consider Elizabeth Warren’s “This Fight Is Our Fight,” reviewed by Paul Krugman and new to the hardcover nonfiction list at No. 1. On its face, the book — subtitled “The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class” — is all about economic issues, and the index is correspondingly flecked with terms like “layoffs” (one citation), “manufacturing decline” (one citation) and “rent assistance” (two citations). But really these are just the parsley on the meatloaf. Flip through the back pages and it’s clear that Warren, the hard-punching Massachusetts senator, has a more personal fight in mind: The index listing for “Trump, Donald” is divided into dozens of subcategories beginning with “bait-and-switch and” (two citations), then moving on to “bigotry and” (four citations), “corporate influences on” (five citations) and “trickle-down and” (seven citations). There are also listings for “tax returns and,” “‘nasty woman’ comment of” and — my favorite — “tweetstorms vs.,” which directs readers to a four-page recap of Warren’s social media battle with Trump during the presidential race. “I tweeted about how he cheated hardworking people who had built his hotels and golf courses,” she recalls. “I mentioned his bullying, his attacks on women, his racism, his obvious narcissism. And in that first tweetstorm, I did my best to sound the alarm: This guy is dangerous, and he could end up as president of the United States.”

THE O’REILLY FACTOR: In the cultural economy, the best-seller list is a lagging indicator. Even “instant” books need time to be pitched, approved, written and printed, so it can take months for the list to catch up with the zeitgeist. That’s why it’s too soon to say how Bill O’Reilly’s recent ouster from Fox News over multiple sexual harassment claims might affect the fortunes of Bill O’Reilly, author. For now, though, there are still a couple of O’Reilly titles on the hardcover nonfiction list: “Killing the Rising Sun,” about the end of World War II, is No. 13, and “Old School,” about the importance of traditional values, is No. 4.

AYUH: Anita Shreve’s new novel, “The Stars Are Fire,” about a series of wildfires in 1940s Maine, hits the hardcover fiction list at No. 11. “I seem to be particularly drawn to Maine,” Shreve told WBUR Radio in Boston recently. “There’s a kind of flintiness of character that echoes the jagged rocks and the view of the sea.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Elizabeth Warren Really Does Not Like Donald Trump appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Waterhouse Press Prepares for Misadventures

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Since it was launched in 2014 by bestselling author Meredith Wild, Waterhouse Press has released two romance series that have sold phenomenally well. The company’s first series, Calendar Girl by Audrey Carlan, saw each of its 12 books reach e-book bestseller lists in the U.S., and the series has become a hit overseas: rights have been sold in 31 countries, and the print versions of February and March landed at the top of the bestseller list in France at the beginning of 2017. Waterhouse CEO David Grishman noted that, while Calendar Girl did very well in e-book editions in the U.S., the print editions have sold better than e-books abroad, where e-book penetration is much lower. Overall, Calendar Girl has sold about 4 million units in English (all formats), and while the series has not yet been released in its entirety in all of the 31 countries, international sales in all formats topped 4 million units by the end of 2016.

Waterhouse’s second major series, the Steel Brothers Saga by Helen Hardt, has also seen each of the books released to date hit e-book bestseller lists. Waterhouse acquired the Steel Brothers Saga and other Hardt works in November 2015, and since Waterhouse began releasing the line, it has sold more than 1 million copies across all formats worldwide. Grishman expects unit sales to exceed 2 million by the end of 2017, with three books still to be released.

Beginning this fall, Waterhouse is hoping for another breakout success with Misadventures. As conceived by Wild, Misadventures will be fun, quick reads (about 50,000 words) that “will be high on steam, light on plot.” The first book in the series will be Misadventures of a City Girl by Wild and Chelle Bliss, due out September 12. Seven books are planned for the fall and more for spring 2018. “It will be our flagship product next year,” Grishman said. Each of the authors who have signed on to write for Misadventures has agreed to do at least three books, but Grishman is hoping that if the line is successful they will do more. His ideal schedule would be to release a Misadventure title every few weeks in 2018.

The publication of Misadventures will be the first time Waterhouse has released books in hardcover; currently, it has limited print publication to trade paperback. “We think readers may want to collect the books in the series,” Wild explained. Grishman said one of his goals for 2017 is to raise print’s share of Waterhouse’s sales from 16% to 25%.

Wild will cowrite four of the fall Misadventure books and at least one next year. Although she previously sold her self-published Hacker series to Grand Central’s Forever imprint, she said any new books she writes will be done for Waterhouse. “Selling the rights to Hacker was one of the hardest things I have ever done,” Wild said. (She declined to say whether she would like to buy her rights back at some point.)

It is that experience that lets Wild empathize with Waterhouse’s eight other authors. “I know how personal books can be to an author,” she said. Because of that, Waterhouse will continue to promote books well beyond their initial releases and work to build a community of readers for each author. Wild also said Waterhouse’s contracts are different from those of larger houses, although she didn’t disclose details.

To help grow the business, within the past year Waterhouse has added Scott Saunders as managing editor and Jeanne De Vita as development editor; Waterhouse now has a staff of 10. Waterhouse is also taking some functions it has outsourced in the past, such as rights sales, in-house, although it will continue to use Ingram Publisher Services for print distribution.

For all of its early success, Grishman said Waterhouse is still “fine-tuning [its] process” and that he sees the release of Misadventures as a chance to prove the company isn’t “a one-trick pony.”

A version of this article appeared in the 05/01/2017 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: Waterhouse Press Prepares for Misadventures

The post Waterhouse Press Prepares for Misadventures appeared first on Art of Conversation.

The Book Review Podcast: Sheryl Sandberg on Life After Tragedy

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:08 pm.

Source link

Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant talk about “Option B,” and Annie Jacobsen discusses “Phenomena.”

Source link

The post The Book Review Podcast: Sheryl Sandberg on Life After Tragedy appeared first on Art of Conversation.

April 28, 2017

B&N's New CEO Must Step Up Its Sales

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

As the new head of Barnes & Noble, Demos Parneros knows his top priority is to stop the sales slide that has plagued the company’s retail stores.

Source link

The post B&N's New CEO Must Step Up Its Sales appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Solving a Reign of Terror Against Native Americans

This content was originally published by DAVE EGGERS on 28 April 2017 | 9:29 pm.

Source link

No one argued the point at the time. No one but the Osage knew there was oil under that rocky soil. The Osage leased the land to prospectors and made a fortune. “In 1923 alone,” Grann writes, “the tribe took in more than $30 million, the equivalent today of more than $400 million. The Osage were considered the wealthiest people per capita in the world.” They built mansions and bought fleets of cars. A magazine writer at the time wrote: “Every time a new well is drilled the Indians are that much richer. … The Osage Indians are becoming so rich that something will have to be done about it.”

Indeed. The federal government, ostensibly concerned about the Osage Indians’ ability to manage their windfall, required many Osage Indians — those it classified as “incompetent” — to have a guardian oversee the management and spending of their money. Full-blooded Indians could expect to be deemed “incompetent” and in need of oversight, whereas those of mixed blood were allowed to manage their own affairs. Not surprisingly, the Osage became popular targets for theft, graft and mercenary marriage. A white woman sent a letter to the tribe, offering herself to any willing Osage bachelor: “Will you please tell the richest Indian you know of, and he will find me as good and true as any human being can be.”

Grann approaches his narrative by way of Mollie Burkhart, a full member of the Osage tribe and one of four sisters who all became wealthy and married white men. But despite their windfall, their lives were fraught and ended too soon. Her sister Minnie died at 27 of what doctors ruled a “peculiar wasting illness.” A few years later, her sister Anna, who was known to enjoy speakeasies and whiskey, left one night and never came home. Her body was found a week later in a ravine. She had been shot in the head.

Continue reading the main story

Another Osage member, Charles Whitehorn, was found shot within days of the discovery of Anna’s body. Both he and Anna had been killed with small-caliber bullets. “Two Separate Murder Cases Are Unearthed Almost at Same Time,” a newspaper headline declared. Two months after Anna’s body was found, her mother, Lizzie, also died of the same vague wasting “disease” that had claimed Minnie. When another sister turned up dead in a suspicious fire, leaving Mollie as the last of her family alive, she was terrified. Someone or something was killing not just the members of her family but Osage Indians en masse — hence the first half of Grann’s subtitle, “The Osage Murders and the Birth of the F.B.I.”

Continue reading the main story

Nine months after the deaths of Anna Brown and Charles Whitehorn, a champion Osage steer roper named William Stepson died of an apparent poisoning. Two more Osage died in the ensuing months, both of suspected poisonings. A couple was blown up by a nitroglycerin bomb while they slept in their bed. The killing continued, with more than two dozen people — not just Osage Indians but also white investigators sent to look into the crimes — killed between 1920 and 1924. It became known as the Osage Reign of Terror.

The second part of Grann’s subtitle nods to the fitful investigation into the killings and their role in shaping the modern F.B.I. In the 1920s, law enforcement was typically conducted by a patchwork of sheriffs, private detectives and vigilantes. The sheriff of Osage County at the time was Harve M. Freas, 58, who weighed 300 pounds and was rumored to cavort with bootleggers and gamblers. He had done nothing to determine who was killing the Osage Indians, so the tribe asked Barney McBride, a white oilman they trusted, to go to Washington, D.C., to insist the federal government intervene. A day after he arrived, McBride’s body was found in a Maryland culvert. He was naked and had been stabbed over 20 times. “Conspiracy Believed to Kill Rich Indians,” The Washington Post’s headline read.

Continue reading the main story

The Federal Bureau of Investigation was created by Theodore Roosevelt in 1908, to fill in gaps in jurisdiction and assist where local enforcement was overmatched. By the 1920s, though, it was still relatively small, with only a few hundred agents and a handful of offices around the country. Most important, the bureau’s agents were not trusted. Known for bending laws and getting cozy with criminals, the Department of Justice, Grann writes, “had become known as the Department of Easy Virtue.”

Continue reading the main story

That changed in 1924, when J. Edgar Hoover was appointed the director of the F.B.I. He was not a likely choice. He had been deputy director under Burns, but was only 29 and had never been a detective. He was diminutive, struggled with a stutter and a fear of germs, and lived with his mother. But he was zealous and organized, and had a vision for the bureau. He insisted that all agents have some background in law or accounting; that they wear dark suits and ties; that they abstain from alcohol and be models of personal propriety; and that they use new, scientific methods of sleuthing, including fingerprint identification, ballistics, handwriting analysis and phone-tapping.

The Osage murders would be Hoover’s first significant test of the new F.B.I.’s abilities.

Given that so many investigators had already failed or had been murdered in pursuit of the killers, Hoover needed the sturdiest and most incorruptible of agents to head up the investigation. He chose Tom White, a Texan myth of a man. White’s father was the local sheriff in Austin, so Tom grew up in a home attached to the county jail. He and two brothers eventually became Texas Rangers. Looking for a more stable life, White became an F.B.I. agent.

White was empowered to put his own team together, most of whom would insinuate themselves into Osage undercover. One older agent entered town as an elderly cattle rancher. Another agent, a former insurance salesman, set up a real insurance office in town. And John Wren, part Ute Indian — one of the F.B.I.’s few Native Americans — arrived as an Indian medicine man hoping to find his relatives.

If this all sounds like the plot of a detective novel, you have fallen under the spell of David Grann’s brilliance. In his previous two books, “The Lost City of Z,” about the search for the golden Amazonian city of El Dorado, and “The Devil and Sherlock Holmes,” a varied collection of journalism, Grann has proved himself a master of spinning delicious, many-layered mysteries that also happen to be true. As a reporter he is dogged and exacting, with a singular ability to uncover and incorporate obscure journals, depositions and ledgers without ever letting the plot sag. As a writer he is generous of spirit, willing to give even the most scurrilous of characters the benefit of the doubt.

Thus, when Tom White and his men solve the crime, and the mastermind behind the murders is revealed, you will not see it coming. You will feel that familiar thrill at having been successfully misdirected, but then there are about 70 pages left in the book. And in these last pages, Grann takes what was already a fascinating and disciplined recording of a forgotten chapter in American history, and with the help of contemporary Osage tribe members, he illuminates a sickening conspiracy that goes far deeper than those four years of horror. It will sear your soul. Among the towering thefts and crimes visited upon the native peoples of the continent, what was done to the Osage must rank among the most depraved and ignoble. “This land is saturated with blood,” says Mary Jo Webb, an Osage Indian alive today and still trying to understand the crimes of the past. “History,” Grann writes in this shattering book, “is a merciless judge.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Solving a Reign of Terror Against Native Americans appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Do You Remember the Card Catalogue?

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

When it comes to libraries, there are a couple of ways to size up your next delicious read: you can walk up and down the stacks, picking over titles and authors, weighing prospects by subject or heft; or you can dive into the catalogue and sort through the options there.

For most of my life, going for that second option meant approaching a gigantic oaken chest of small drawers with brass handles and label holders—the card catalogue. For many of us, it’s still a favorite piece of furniture, although as cataloguing has gone digital, it’s been replaced by computer terminals in most libraries.

But even in the days of card-based cataloguing, and certainly since, the Library of Congress has made the fruits of its data-collection effort available to other libraries in the U.S. and around the world, a labor-saving offering that has allowed libraries globally to focus on the myriad other duties of librarianship. I speak for my colleagues and I think my predecessors when I say, “You’re very welcome.”

Here at the Library of Congress, where we were pioneers in electronic cataloguing in the 1960s and 1970s, the old Main Reading Room card catalogue still lines a block-long wall in the subbasement of our Madison Building, providing supplemental information to our research librarians and a warm feeling to our staff.

If you, like me, retain a special place in your heart for the dog-eared cards of a physical catalogue, you might well enjoy The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures, a book the Library of Congress is releasing in cooperation with Chronicle Books in time for 2017’s National Library Week. The Card Catalog lays out the history of card cataloguing and includes images of famous cards and books, from our own collections (including the handwritten annotations we prize—which is one of the reasons we hang onto the old physical catalogues).

Not every accrued piece of wisdom makes it across the digital line. The theme for this year’s National Library Week is “Libraries Transform.” Libraries transform us, and they transform themselves. Cataloging began to move from oaken chests to computers five decades ago, and now that most people expect to access knowledge through search engines, it’s time for another transformation, through Bibframe, a bibliographic framework initiative the Library of Congress is leading to link catalogued library collections to the internet.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the towering computer scientist Henriette Avram came to the library to lead a program to computerize catalogues and link libraries via computer. Known as MARC, for machine-readable cataloguing, it took the bibliographic world by storm. Within just a few years, MARC became the standard for all cataloguing across the U.S. and internationally. MARC and its successors, MARC21 and MARCXML, have served us well for more than half a century.

But in the past decade it has become clear that a new method must be created to get this information out of the libraries and into patrons’ hands through the web. It’s time to connect our library tributary to the big river of the internet.

The work ahead is already underway, with advice from our longtime MARC partners the American Library Association, the Online Computer Library Center, the British Library, the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek, Libraries and Archive Canada, and others. Even as our collaborations move forward, MARC must be maintained to meet immediate needs. And care is being taken to ensure that the final result will be useful to all kinds of libraries, large and small, research and public. When this framework ultimately unfolds, the riches of more than a century of cataloguing will eventually be available to library patrons from any computer—and increasingly, so will the books themselves.

But for that full sensory experience—feeling the roughness of the paper, marveling at the workmanship of bindings, catching a whiff of that old-book perfume—you’ll just have to go to the library.

Carla Hayden, a former president of the American Library Association, was sworn in as the 14th librarian of Congress on Sept. 14, 2016. She is the first woman and the first African-American to lead the nation’s library.

A version of this article appeared in the 05/01/2017 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: Remember the Card Catalogue?

The post Do You Remember the Card Catalogue? appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Monthly StatShot, November 2016

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Adult trade sales rose 6.8% in November 2016, while sales in the children’s/young adult segment jumped 16.2%, according to figures released by the AAP as part of its StatShot program.

Source link

The post Monthly StatShot, November 2016 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

A Kitsch-Filled Writer’s Room for John Waters

This content was originally published by on 28 April 2017 | 9:49 pm.

Source link

The film director and author lives in a 1927 Italianate-style house. A second-floor writing space has lots of pop-culture ephemera.

Source link

The post A Kitsch-Filled Writer’s Room for John Waters appeared first on Art of Conversation.