Andrew Lam's Blog - Posts Tagged "environment"

In Thailand, Elephant Sashimi is All the Rage

SAN FRANCISCO -- In Asia, there's an ongoing irony that deepens as the natural world dwindles to the size of a parking lot. Wild animals, once revered and assigned all kinds of spiritual meaning, are increasingly ending up as the main entree.

The tiger, for instance, that fierce and terror-inducing king of the jungle, is no longer feared so much as coveted: as a rug, as jewelry made of fangs, as a quixotic dish, or as medicinal products made from its various parts - bones and penis and gall bladder - thought to improve man's sexual prowess.

But nowhere is the irony as deep as it is in Thailand, where the regal elephant is now being served up alongside the tiger: on a fanciful diner's plate.

According to a recent Associated Press article, a new taste for elephant meat has sprung up in mega-modern Thailand.

Traditional poaching for male elephant tusks has evolved, with a growing taste for their meat driving hunters to begin targeting female and baby elephants as well. Not exactly a traditional Thai delicacy, the emergence of an army of nouveaux riches across East Asia has fueled ever-more garish culinary trends.

Elephant sashimi, now apparently all the rage, is part of a mindset at once boastful and shallow - if it's the last elephant, then I will show my friends that I can afford it.

So here's the irony: The Asian elephant is still a revered cultural icon in Thailand, gracing bas-reliefs of temples and ancient paintings of battle scenes, but it is fast disappearing. The country whose civilization was more or less built on the elephant's back is now turning its back on the animal.

Indeed, the elephant once served as both builder and war machine: carrying logs and rocks and uprooting trees to build palaces and temples, while fighting countless wars bedecked in the armor of a warrior.

Within Buddhism, Thailand’s state religion and a binding force across much of the region, the elephant remains sacred. According to legend, a white Elephant appeared in the dream of Queen Maya, holding a white lotus flower in its trunk. She later gave birth to the historical Gautama Buddha, Siddhārtha.

Alas, sacred is quickly cast off for cold hard cash. An elephant penis can now fetch as high as $1,000 and a pair of tusks as high as $63,000. Though illegal, poaching has now reached what environmentalists are calling a "crisis point."

At the beginning of last century there were more than 100,000 wild elephants in existence. One hundred years later the population has plummeted to less than 3,000.

Classified as an endangered species, the Asian elephant is expected to disappear from the wild altogether around 2050, if not sooner.

But while poaching is particularly abhorrent, there are other reasons behind the elephant’s disappearance, including deforestation.

For domesticated elephants in Thailand, deforestation means no more jobs. Logging in Thailand's forests has long relied on the strength of the powerful pachyderms. An elephant can pull half its weight and carry 600 kilos on its back. In hilly countryside where roads are small and inaccessible to trucks, an elephant is indispensable for the timber business. But logging is all but illegal now in Thailand, and the domesticated elephant, it seems, is out of luck.

An average elephant weighs 11,000 pounds, and consumes more than 26 gallons of water and 440 pounds of food a day. That's why their owners consciously curb breeding among the captive beasts, bringing down their number even farther.

Many owners, left with no other choice, have now turned their elephants into urban beggars. For the wild elephant conditions are even worse.

Only about 15 percent of the country is still forestland, and those patches are widely scattered. Many wild elephants resort to raiding farms for crops, where they are often shot or poisoned by subsistence farmers. In the story of miserable beast pitted against impoverished human it’s a no brainer who comes out on top… with fork in hand.

Man has conquered everything but himself. The wild is now what we call a reserve, the wilderness nowhere but within. In a world where even the sacred is devoured, one can't help but wonder what are the chances for other species on the endangered list.

NAM editor Andrew Lam is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, "Birds of Paradise," is due out in 2013.

The tiger, for instance, that fierce and terror-inducing king of the jungle, is no longer feared so much as coveted: as a rug, as jewelry made of fangs, as a quixotic dish, or as medicinal products made from its various parts - bones and penis and gall bladder - thought to improve man's sexual prowess.

But nowhere is the irony as deep as it is in Thailand, where the regal elephant is now being served up alongside the tiger: on a fanciful diner's plate.

According to a recent Associated Press article, a new taste for elephant meat has sprung up in mega-modern Thailand.

Traditional poaching for male elephant tusks has evolved, with a growing taste for their meat driving hunters to begin targeting female and baby elephants as well. Not exactly a traditional Thai delicacy, the emergence of an army of nouveaux riches across East Asia has fueled ever-more garish culinary trends.

Elephant sashimi, now apparently all the rage, is part of a mindset at once boastful and shallow - if it's the last elephant, then I will show my friends that I can afford it.

So here's the irony: The Asian elephant is still a revered cultural icon in Thailand, gracing bas-reliefs of temples and ancient paintings of battle scenes, but it is fast disappearing. The country whose civilization was more or less built on the elephant's back is now turning its back on the animal.

Indeed, the elephant once served as both builder and war machine: carrying logs and rocks and uprooting trees to build palaces and temples, while fighting countless wars bedecked in the armor of a warrior.

Within Buddhism, Thailand’s state religion and a binding force across much of the region, the elephant remains sacred. According to legend, a white Elephant appeared in the dream of Queen Maya, holding a white lotus flower in its trunk. She later gave birth to the historical Gautama Buddha, Siddhārtha.

Alas, sacred is quickly cast off for cold hard cash. An elephant penis can now fetch as high as $1,000 and a pair of tusks as high as $63,000. Though illegal, poaching has now reached what environmentalists are calling a "crisis point."

At the beginning of last century there were more than 100,000 wild elephants in existence. One hundred years later the population has plummeted to less than 3,000.

Classified as an endangered species, the Asian elephant is expected to disappear from the wild altogether around 2050, if not sooner.

But while poaching is particularly abhorrent, there are other reasons behind the elephant’s disappearance, including deforestation.

For domesticated elephants in Thailand, deforestation means no more jobs. Logging in Thailand's forests has long relied on the strength of the powerful pachyderms. An elephant can pull half its weight and carry 600 kilos on its back. In hilly countryside where roads are small and inaccessible to trucks, an elephant is indispensable for the timber business. But logging is all but illegal now in Thailand, and the domesticated elephant, it seems, is out of luck.

An average elephant weighs 11,000 pounds, and consumes more than 26 gallons of water and 440 pounds of food a day. That's why their owners consciously curb breeding among the captive beasts, bringing down their number even farther.

Many owners, left with no other choice, have now turned their elephants into urban beggars. For the wild elephant conditions are even worse.

Only about 15 percent of the country is still forestland, and those patches are widely scattered. Many wild elephants resort to raiding farms for crops, where they are often shot or poisoned by subsistence farmers. In the story of miserable beast pitted against impoverished human it’s a no brainer who comes out on top… with fork in hand.

Man has conquered everything but himself. The wild is now what we call a reserve, the wilderness nowhere but within. In a world where even the sacred is devoured, one can't help but wonder what are the chances for other species on the endangered list.

NAM editor Andrew Lam is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, "Birds of Paradise," is due out in 2013.

In Thailand, Elephant Sashimi is All the Rage

SAN FRANCISCO -- In Asia, there's an ongoing irony that deepens as the natural world dwindles to the size of a parking lot. Wild animals, once revered and assigned all kinds of spiritual meaning, are increasingly ending up as the main entree.

The tiger, for instance, that fierce and terror-inducing king of the jungle, is no longer feared so much as coveted: as a rug, as jewelry made of fangs, as a quixotic dish, or as medicinal products made from its various parts - bones and penis and gall bladder - thought to improve man's sexual prowess.

But nowhere is the irony as deep as it is in Thailand, where the regal elephant is now being served up alongside the tiger: on a fanciful diner's plate.

According to a recent Associated Press article, a new taste for elephant meat has sprung up in mega-modern Thailand.

Traditional poaching for male elephant tusks has evolved, with a growing taste for their meat driving hunters to begin targeting female and baby elephants as well. Not exactly a traditional Thai delicacy, the emergence of an army of nouveaux riches across East Asia has fueled ever-more garish culinary trends.

Elephant sashimi, now apparently all the rage, is part of a mindset at once boastful and shallow - if it's the last elephant, then I will show my friends that I can afford it.

So here's the irony: The Asian elephant is still a revered cultural icon in Thailand, gracing bas-reliefs of temples and ancient paintings of battle scenes, but it is fast disappearing. The country whose civilization was more or less built on the elephant's back is now turning its back on the animal.

Indeed, the elephant once served as both builder and war machine: carrying logs and rocks and uprooting trees to build palaces and temples, while fighting countless wars bedecked in the armor of a warrior.

Within Buddhism, Thailand’s state religion and a binding force across much of the region, the elephant remains sacred. According to legend, a white Elephant appeared in the dream of Queen Maya, holding a white lotus flower in its trunk. She later gave birth to the historical Gautama Buddha, Siddhārtha.

Alas, sacred is quickly cast off for cold hard cash. An elephant penis can now fetch as high as $1,000 and a pair of tusks as high as $63,000. Though illegal, poaching has now reached what environmentalists are calling a "crisis point."

At the beginning of last century there were more than 100,000 wild elephants in existence. One hundred years later the population has plummeted to less than 3,000.

Classified as an endangered species, the Asian elephant is expected to disappear from the wild altogether around 2050, if not sooner.

But while poaching is particularly abhorrent, there are other reasons behind the elephant’s disappearance, including deforestation.

For domesticated elephants in Thailand, deforestation means no more jobs. Logging in Thailand's forests has long relied on the strength of the powerful pachyderms. An elephant can pull half its weight and carry 600 kilos on its back. In hilly countryside where roads are small and inaccessible to trucks, an elephant is indispensable for the timber business. But logging is all but illegal now in Thailand, and the domesticated elephant, it seems, is out of luck.

An average elephant weighs 11,000 pounds, and consumes more than 26 gallons of water and 440 pounds of food a day. That's why their owners consciously curb breeding among the captive beasts, bringing down their number even farther.

Many owners, left with no other choice, have now turned their elephants into urban beggars. For the wild elephant conditions are even worse.

Only about 15 percent of the country is still forestland, and those patches are widely scattered. Many wild elephants resort to raiding farms for crops, where they are often shot or poisoned by subsistence farmers. In the story of miserable beast pitted against impoverished human it’s a no brainer who comes out on top… with fork in hand.

Man has conquered everything but himself. The wild is now what we call a reserve, the wilderness nowhere but within. In a world where even the sacred is devoured, one can't help but wonder what are the chances for other species on the endangered list.

NAM editor Andrew Lam is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, "Birds of Paradise," is due out in 2013.

The tiger, for instance, that fierce and terror-inducing king of the jungle, is no longer feared so much as coveted: as a rug, as jewelry made of fangs, as a quixotic dish, or as medicinal products made from its various parts - bones and penis and gall bladder - thought to improve man's sexual prowess.

But nowhere is the irony as deep as it is in Thailand, where the regal elephant is now being served up alongside the tiger: on a fanciful diner's plate.

According to a recent Associated Press article, a new taste for elephant meat has sprung up in mega-modern Thailand.

Traditional poaching for male elephant tusks has evolved, with a growing taste for their meat driving hunters to begin targeting female and baby elephants as well. Not exactly a traditional Thai delicacy, the emergence of an army of nouveaux riches across East Asia has fueled ever-more garish culinary trends.

Elephant sashimi, now apparently all the rage, is part of a mindset at once boastful and shallow - if it's the last elephant, then I will show my friends that I can afford it.

So here's the irony: The Asian elephant is still a revered cultural icon in Thailand, gracing bas-reliefs of temples and ancient paintings of battle scenes, but it is fast disappearing. The country whose civilization was more or less built on the elephant's back is now turning its back on the animal.

Indeed, the elephant once served as both builder and war machine: carrying logs and rocks and uprooting trees to build palaces and temples, while fighting countless wars bedecked in the armor of a warrior.

Within Buddhism, Thailand’s state religion and a binding force across much of the region, the elephant remains sacred. According to legend, a white Elephant appeared in the dream of Queen Maya, holding a white lotus flower in its trunk. She later gave birth to the historical Gautama Buddha, Siddhārtha.

Alas, sacred is quickly cast off for cold hard cash. An elephant penis can now fetch as high as $1,000 and a pair of tusks as high as $63,000. Though illegal, poaching has now reached what environmentalists are calling a "crisis point."

At the beginning of last century there were more than 100,000 wild elephants in existence. One hundred years later the population has plummeted to less than 3,000.

Classified as an endangered species, the Asian elephant is expected to disappear from the wild altogether around 2050, if not sooner.

But while poaching is particularly abhorrent, there are other reasons behind the elephant’s disappearance, including deforestation.

For domesticated elephants in Thailand, deforestation means no more jobs. Logging in Thailand's forests has long relied on the strength of the powerful pachyderms. An elephant can pull half its weight and carry 600 kilos on its back. In hilly countryside where roads are small and inaccessible to trucks, an elephant is indispensable for the timber business. But logging is all but illegal now in Thailand, and the domesticated elephant, it seems, is out of luck.

An average elephant weighs 11,000 pounds, and consumes more than 26 gallons of water and 440 pounds of food a day. That's why their owners consciously curb breeding among the captive beasts, bringing down their number even farther.

Many owners, left with no other choice, have now turned their elephants into urban beggars. For the wild elephant conditions are even worse.

Only about 15 percent of the country is still forestland, and those patches are widely scattered. Many wild elephants resort to raiding farms for crops, where they are often shot or poisoned by subsistence farmers. In the story of miserable beast pitted against impoverished human it’s a no brainer who comes out on top… with fork in hand.

Man has conquered everything but himself. The wild is now what we call a reserve, the wilderness nowhere but within. In a world where even the sacred is devoured, one can't help but wonder what are the chances for other species on the endangered list.

NAM editor Andrew Lam is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, "Birds of Paradise," is due out in 2013.

Giving up a car is a new American responsibility

San Francisco - For the first time in over two decades, I am no longer a driver. Facing spiking gas prices and much-needed repairs, I finally donated my Toyota Corolla to an organization that takes care of orphans.

It's an odd feeling to be on this side of being green. Without a car, my sense of time and space has been immediately altered. What was once a matter of expediency is now an effortful navigation.

"I'll be there in 15 minutes!" I used to tell a good friend who once lived nearby but who now resides, without a car, at an inconvenient distance. Going to my favorite Asian food market suddenly has turned into another arduous chore: Once a 30-minute event, it has become a two-hour ordeal, with bags in hands, and bus transfers.

Indeed when I came to San Francisco from Vietnam with my family at the end of the Vietnam War, I remember such delight when my older brother bought his first car. We were still sharing an apartment with my aunt and her children, but as we cruised the streets at night, it felt as if we were becoming Americans.

The automobile, after all, is intrinsically American, and owning one largely determines how we arrange our daily lives; it is as essential to us as the train and metro are to the Japanese or Europeans. Indeed, a car is the first thing an American teenager of driving age desires; to drive away from home is an established American rite of passage. Even the working poor are drivers here.

For immigrants, the car is the first thing we buy before the house. Vietnamese in Vietnam marvel at the BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes that their relatives drive in America, and no doubt the sleek photos sent home cause many to dream of a life of luxury in the United States.

It seems a natural progression that the housing crisis should quickly lend itself to a car crisis. Both were readily available at one time, with easy loans and cheap gas. But now, with skyrocketing gas prices and faltering mortgages, many have had to give up one in order to keep the other.

Not surprisingly, the car is often the last thing that downtrodden Americans let go. "I can see losing my house, but I can't imagine losing my van," one unemployed friend told me. "I can live in my van. But not being able to get where I need to go would be worst than not having a house."

Mobility defines us far more than sedentary life, thus, the car is arguably more important than the house. Americans, despite accepting global warming as de facto, are still very much in love with the automobile. On average, we own 2.28 vehicles per household.

Addiction

Our addiction to the automobile is as much a symptom of our nomadic culture as it is a matter of necessity: Urban sprawl, combined with little public transportation, makes the car essential. A job seems almost always to require it. The distance between here and there is daunting without a vehicle at one's command.

The car, culturally speaking, is mobility and individualism combined. It is sex, freedom and danger. Thelma and Louise escaped from urban ennui by hitting the freeway with the wind in their hair, the horizon shimmering chimerically ahead. They found romance on the road. Indeed, their final moment approaches the mythic, as the blue Thunderbird Convertible flies across the Grand Canyon, taking the notion of freedom beyond any open road.

Our civilization, too, is driving toward an abyss. The covetous American way of life in the age of climate change and dwindling energy resources has become unsustainable.

Former Vice President turned eco-activist Al Gore called for a radical change in our collective behavior a few years back. He wanted us to completely replace fossil fuel-generated electricity with carbon-free energy sources like solar, wind and geothermal by 2018.

"The survival of the United States of America as we know it is at risk," he said. "The future of human civilization is at stake." We are now being called upon, the Nobel Prize winner told us, "to move quickly and boldly to shake off complacency, throw aside old habits and rise, clear-eyed and alert, to the necessity of big changes."

I wish he were exaggerating, but my gut tells me that the green guru is pointing us in the right direction. How and if we'll ever get there, how we'll find a collective will to act, I have no idea. But I do know this: Humanity has arrived at a historic juncture and it now seems that a drastic shift in the collective behavior is called for. If this means finding the will to be frugal and give up certain luxuries, then so be it.

Disposable

America was built on the premise of progress and expansion. Yet our vision of a future of unimpeded opportunities and comfort is now in conflict with the health of the planet. The consumer culture requires continuous acquisition, and it is built on the concept of disposable goods. And it's unfortunate that consumer culture now that defines much of the world. Our way of life has created an unprecedented crisis on a planetary scale.

I can tell you from experience, however, that being on the right side of the green divide is not easy. As I trudged to work this morning, a 40-minute trek, I dearly missed my car. As I budget my time and memorize bus routes and timetables, it seems as if I am returning to my humble immigrant beginnings, repudiating some notion of being an American.

But I'm not. Because I can, giving up the car is my new American responsibility.

New America Media editor, Andrew Lam, is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres" and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, Birds of Paradise, a collection of short stories, will be published in 2013.

It's an odd feeling to be on this side of being green. Without a car, my sense of time and space has been immediately altered. What was once a matter of expediency is now an effortful navigation.

"I'll be there in 15 minutes!" I used to tell a good friend who once lived nearby but who now resides, without a car, at an inconvenient distance. Going to my favorite Asian food market suddenly has turned into another arduous chore: Once a 30-minute event, it has become a two-hour ordeal, with bags in hands, and bus transfers.

Indeed when I came to San Francisco from Vietnam with my family at the end of the Vietnam War, I remember such delight when my older brother bought his first car. We were still sharing an apartment with my aunt and her children, but as we cruised the streets at night, it felt as if we were becoming Americans.

The automobile, after all, is intrinsically American, and owning one largely determines how we arrange our daily lives; it is as essential to us as the train and metro are to the Japanese or Europeans. Indeed, a car is the first thing an American teenager of driving age desires; to drive away from home is an established American rite of passage. Even the working poor are drivers here.

For immigrants, the car is the first thing we buy before the house. Vietnamese in Vietnam marvel at the BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes that their relatives drive in America, and no doubt the sleek photos sent home cause many to dream of a life of luxury in the United States.

It seems a natural progression that the housing crisis should quickly lend itself to a car crisis. Both were readily available at one time, with easy loans and cheap gas. But now, with skyrocketing gas prices and faltering mortgages, many have had to give up one in order to keep the other.

Not surprisingly, the car is often the last thing that downtrodden Americans let go. "I can see losing my house, but I can't imagine losing my van," one unemployed friend told me. "I can live in my van. But not being able to get where I need to go would be worst than not having a house."

Mobility defines us far more than sedentary life, thus, the car is arguably more important than the house. Americans, despite accepting global warming as de facto, are still very much in love with the automobile. On average, we own 2.28 vehicles per household.

Addiction

Our addiction to the automobile is as much a symptom of our nomadic culture as it is a matter of necessity: Urban sprawl, combined with little public transportation, makes the car essential. A job seems almost always to require it. The distance between here and there is daunting without a vehicle at one's command.

The car, culturally speaking, is mobility and individualism combined. It is sex, freedom and danger. Thelma and Louise escaped from urban ennui by hitting the freeway with the wind in their hair, the horizon shimmering chimerically ahead. They found romance on the road. Indeed, their final moment approaches the mythic, as the blue Thunderbird Convertible flies across the Grand Canyon, taking the notion of freedom beyond any open road.

Our civilization, too, is driving toward an abyss. The covetous American way of life in the age of climate change and dwindling energy resources has become unsustainable.

Former Vice President turned eco-activist Al Gore called for a radical change in our collective behavior a few years back. He wanted us to completely replace fossil fuel-generated electricity with carbon-free energy sources like solar, wind and geothermal by 2018.

"The survival of the United States of America as we know it is at risk," he said. "The future of human civilization is at stake." We are now being called upon, the Nobel Prize winner told us, "to move quickly and boldly to shake off complacency, throw aside old habits and rise, clear-eyed and alert, to the necessity of big changes."

I wish he were exaggerating, but my gut tells me that the green guru is pointing us in the right direction. How and if we'll ever get there, how we'll find a collective will to act, I have no idea. But I do know this: Humanity has arrived at a historic juncture and it now seems that a drastic shift in the collective behavior is called for. If this means finding the will to be frugal and give up certain luxuries, then so be it.

Disposable

America was built on the premise of progress and expansion. Yet our vision of a future of unimpeded opportunities and comfort is now in conflict with the health of the planet. The consumer culture requires continuous acquisition, and it is built on the concept of disposable goods. And it's unfortunate that consumer culture now that defines much of the world. Our way of life has created an unprecedented crisis on a planetary scale.

I can tell you from experience, however, that being on the right side of the green divide is not easy. As I trudged to work this morning, a 40-minute trek, I dearly missed my car. As I budget my time and memorize bus routes and timetables, it seems as if I am returning to my humble immigrant beginnings, repudiating some notion of being an American.

But I'm not. Because I can, giving up the car is my new American responsibility.

New America Media editor, Andrew Lam, is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres" and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, Birds of Paradise, a collection of short stories, will be published in 2013.

Published on March 21, 2012 15:05

•

Tags:

al-gore, automobile, car, driving, economy, environment, gas, green, oil, petroleum, prices, public, transportation

Giving up a car is a new American responsibility

San Francisco - For the first time in over two decades, I am no longer a driver. Facing spiking gas prices and much-needed repairs, I finally donated my Toyota Corolla to an organization that takes care of orphans.

It's an odd feeling to be on this side of being green. Without a car, my sense of time and space has been immediately altered. What was once a matter of expediency is now an effortful navigation.

"I'll be there in 15 minutes!" I used to tell a good friend who once lived nearby but who now resides, without a car, at an inconvenient distance. Going to my favorite Asian food market suddenly has turned into another arduous chore: Once a 30-minute event, it has become a two-hour ordeal, with bags in hands, and bus transfers.

Indeed when I came to San Francisco from Vietnam with my family at the end of the Vietnam War, I remember such delight when my older brother bought his first car. We were still sharing an apartment with my aunt and her children, but as we cruised the streets at night, it felt as if we were becoming Americans.

The automobile, after all, is intrinsically American, and owning one largely determines how we arrange our daily lives; it is as essential to us as the train and metro are to the Japanese or Europeans. Indeed, a car is the first thing an American teenager of driving age desires; to drive away from home is an established American rite of passage. Even the working poor are drivers here.

For immigrants, the car is the first thing we buy before the house. Vietnamese in Vietnam marvel at the BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes that their relatives drive in America, and no doubt the sleek photos sent home cause many to dream of a life of luxury in the United States.

It seems a natural progression that the housing crisis should quickly lend itself to a car crisis. Both were readily available at one time, with easy loans and cheap gas. But now, with skyrocketing gas prices and faltering mortgages, many have had to give up one in order to keep the other.

Not surprisingly, the car is often the last thing that downtrodden Americans let go. "I can see losing my house, but I can't imagine losing my van," one unemployed friend told me. "I can live in my van. But not being able to get where I need to go would be worst than not having a house."

Mobility defines us far more than sedentary life, thus, the car is arguably more important than the house. Americans, despite accepting global warming as de facto, are still very much in love with the automobile. On average, we own 2.28 vehicles per household.

Addiction

Our addiction to the automobile is as much a symptom of our nomadic culture as it is a matter of necessity: Urban sprawl, combined with little public transportation, makes the car essential. A job seems almost always to require it. The distance between here and there is daunting without a vehicle at one's command.

The car, culturally speaking, is mobility and individualism combined. It is sex, freedom and danger. Thelma and Louise escaped from urban ennui by hitting the freeway with the wind in their hair, the horizon shimmering chimerically ahead. They found romance on the road. Indeed, their final moment approaches the mythic, as the blue Thunderbird Convertible flies across the Grand Canyon, taking the notion of freedom beyond any open road.

Our civilization, too, is driving toward an abyss. The covetous American way of life in the age of climate change and dwindling energy resources has become unsustainable.

Former Vice President turned eco-activist Al Gore called for a radical change in our collective behavior a few years back. He wanted us to completely replace fossil fuel-generated electricity with carbon-free energy sources like solar, wind and geothermal by 2018.

"The survival of the United States of America as we know it is at risk," he said. "The future of human civilization is at stake." We are now being called upon, the Nobel Prize winner told us, "to move quickly and boldly to shake off complacency, throw aside old habits and rise, clear-eyed and alert, to the necessity of big changes."

I wish he were exaggerating, but my gut tells me that the green guru is pointing us in the right direction. How and if we'll ever get there, how we'll find a collective will to act, I have no idea. But I do know this: Humanity has arrived at a historic juncture and it now seems that a drastic shift in the collective behavior is called for. If this means finding the will to be frugal and give up certain luxuries, then so be it.

Disposable

America was built on the premise of progress and expansion. Yet our vision of a future of unimpeded opportunities and comfort is now in conflict with the health of the planet. The consumer culture requires continuous acquisition, and it is built on the concept of disposable goods. And it's unfortunate that consumer culture now that defines much of the world. Our way of life has created an unprecedented crisis on a planetary scale.

I can tell you from experience, however, that being on the right side of the green divide is not easy. As I trudged to work this morning, a 40-minute trek, I dearly missed my car. As I budget my time and memorize bus routes and timetables, it seems as if I am returning to my humble immigrant beginnings, repudiating some notion of being an American.

But I'm not. Because I can, giving up the car is my new American responsibility.

New America Media editor, Andrew Lam, is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres" and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, Birds of Paradise, a collection of short stories, will be published in 2013.

It's an odd feeling to be on this side of being green. Without a car, my sense of time and space has been immediately altered. What was once a matter of expediency is now an effortful navigation.

"I'll be there in 15 minutes!" I used to tell a good friend who once lived nearby but who now resides, without a car, at an inconvenient distance. Going to my favorite Asian food market suddenly has turned into another arduous chore: Once a 30-minute event, it has become a two-hour ordeal, with bags in hands, and bus transfers.

Indeed when I came to San Francisco from Vietnam with my family at the end of the Vietnam War, I remember such delight when my older brother bought his first car. We were still sharing an apartment with my aunt and her children, but as we cruised the streets at night, it felt as if we were becoming Americans.

The automobile, after all, is intrinsically American, and owning one largely determines how we arrange our daily lives; it is as essential to us as the train and metro are to the Japanese or Europeans. Indeed, a car is the first thing an American teenager of driving age desires; to drive away from home is an established American rite of passage. Even the working poor are drivers here.

For immigrants, the car is the first thing we buy before the house. Vietnamese in Vietnam marvel at the BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes that their relatives drive in America, and no doubt the sleek photos sent home cause many to dream of a life of luxury in the United States.

It seems a natural progression that the housing crisis should quickly lend itself to a car crisis. Both were readily available at one time, with easy loans and cheap gas. But now, with skyrocketing gas prices and faltering mortgages, many have had to give up one in order to keep the other.

Not surprisingly, the car is often the last thing that downtrodden Americans let go. "I can see losing my house, but I can't imagine losing my van," one unemployed friend told me. "I can live in my van. But not being able to get where I need to go would be worst than not having a house."

Mobility defines us far more than sedentary life, thus, the car is arguably more important than the house. Americans, despite accepting global warming as de facto, are still very much in love with the automobile. On average, we own 2.28 vehicles per household.

Addiction

Our addiction to the automobile is as much a symptom of our nomadic culture as it is a matter of necessity: Urban sprawl, combined with little public transportation, makes the car essential. A job seems almost always to require it. The distance between here and there is daunting without a vehicle at one's command.

The car, culturally speaking, is mobility and individualism combined. It is sex, freedom and danger. Thelma and Louise escaped from urban ennui by hitting the freeway with the wind in their hair, the horizon shimmering chimerically ahead. They found romance on the road. Indeed, their final moment approaches the mythic, as the blue Thunderbird Convertible flies across the Grand Canyon, taking the notion of freedom beyond any open road.

Our civilization, too, is driving toward an abyss. The covetous American way of life in the age of climate change and dwindling energy resources has become unsustainable.

Former Vice President turned eco-activist Al Gore called for a radical change in our collective behavior a few years back. He wanted us to completely replace fossil fuel-generated electricity with carbon-free energy sources like solar, wind and geothermal by 2018.

"The survival of the United States of America as we know it is at risk," he said. "The future of human civilization is at stake." We are now being called upon, the Nobel Prize winner told us, "to move quickly and boldly to shake off complacency, throw aside old habits and rise, clear-eyed and alert, to the necessity of big changes."

I wish he were exaggerating, but my gut tells me that the green guru is pointing us in the right direction. How and if we'll ever get there, how we'll find a collective will to act, I have no idea. But I do know this: Humanity has arrived at a historic juncture and it now seems that a drastic shift in the collective behavior is called for. If this means finding the will to be frugal and give up certain luxuries, then so be it.

Disposable

America was built on the premise of progress and expansion. Yet our vision of a future of unimpeded opportunities and comfort is now in conflict with the health of the planet. The consumer culture requires continuous acquisition, and it is built on the concept of disposable goods. And it's unfortunate that consumer culture now that defines much of the world. Our way of life has created an unprecedented crisis on a planetary scale.

I can tell you from experience, however, that being on the right side of the green divide is not easy. As I trudged to work this morning, a 40-minute trek, I dearly missed my car. As I budget my time and memorize bus routes and timetables, it seems as if I am returning to my humble immigrant beginnings, repudiating some notion of being an American.

But I'm not. Because I can, giving up the car is my new American responsibility.

New America Media editor, Andrew Lam, is author of "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres" and "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora." His next book, Birds of Paradise, a collection of short stories, will be published in 2013.

Published on March 21, 2012 15:06

•

Tags:

al-gore, automobile, car, driving, economy, environment, gas, green, oil, petroleum, prices, public, transportation

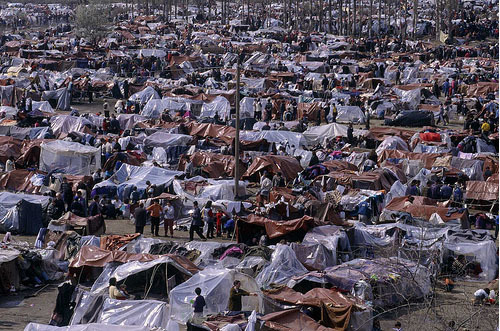

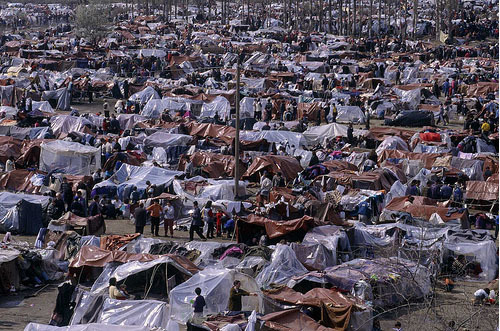

Consequences of Climate Change: A World Awash With Environmental Refugees

The modern world has long thought of refugees in strictly political terms, victims in a world riven by competing ideologies. But as climate change continues unabated, there is a growing population of displaced men, women and children whose homes have been rendered unlivable thanks to a wide spectrum of environmental disasters.

Despite their numbers, and their need, most nations refuse to recognize their status.

The 1951 U.N. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees defines a refugee as a person with a genuine fear of being persecuted for membership in a particular social group or class. The environmental refugee -- not necessarily persecuted, yet necessarily forced to flee -- falls outside this definition.

Not Recognized, Not Counted

Where the forest used to be, torrential rains bring barren hills of mud down on villages. Crops wither in the parched earth. Animals die. Melting glaciers and a rising sea swallow islands and low-lying nations, flooding rice fields with salt water. Factories spew toxic chemicals into rivers and oceans, killing fish and the livelihood of generations.

So people flee. Many become internally displaced, others cross any and all borders in order to survive.

Experts at last year's American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) estimated their numbers would reach 50 million by 2020, due to factors such as agricultural disruption, deforestation, coastal flooding, shoreline erosion, industrial accidents and pollution. Others say the number will triple to 150 million by 2050.

Today, it is believed that the population of environmentally displaced has already far outstripped the number of political refugees worldwide, which according to the United Nation High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) is currently at around 10.2 million.

Still, accurate statistics are hard to come by.

Because the term "environmental refugee" has not been officially recognized, many countries have not bothered to count them, especially if the population is internally displaced. Other countries consider them migrants, and therefore beyond the protection granted refugees.

Another factor obscuring the true scope of the population is the fact that their numbers can rise quite suddenly -- such as after the Fukushima nuclear disaster last year, or Haiti's 2010 earthquake which displaced more than 1 million people -- which makes accounting for their number difficult if not impossible.

In 1999 the International Red Cross put the number of those displaced by environmental disasters at 25 million. In 2009 the UNHCR [United Nation Refugee Agency] estimated that number to be 36 million, 20 million of whom were listed as victims of climate change-related issues.

A "Hidden Crisis" No More

Two decades ago, noted ecologist Norman Myers predicted that humanity was slowly heading toward a "hidden crisis" in which ecosystems would fail to sustain their inhabitants, forcing people off the land to seek shelter elsewhere. After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, however, the crisis became painfully obvious.

As the world watched in awe and horror while hundreds of thousands of displaced Americans scurried across the richest nation on Earth searching for new homes, it became clear that no matter how wealthy or powerful, no country is impervious.

Indeed, being displaced by natural disasters may very well become the central epic of the 21st century. Kiribati, the Maldives and Tuvalu are disappearing as we speak, as the sea level continues to rise. The World Bank estimates that with a 1 meter rise in sea level, Bangladesh would lose close to 20 percent of its land mass, resulting in countless deaths and millions of environmental refugees. Facing present problems of crop failure, destruction of fisheries, loss of biodiversity and flooding, many have already fled to neighboring India, where they endure lives of immense misery and discrimination.

China, in particular, is a hot spot of environmental disasters as it buckles under unsustainable development, giving rise to rapid air pollution and toxic rivers. Alongside desertification, these man-made catastrophes have already left millions displaced.

John Liu, director of the Environmental Education Media Project, spent 25 years in China and witnessed the disasters there. He offered the world this unapologetic, four-alarm warning some years ago: "Every ecosystem on the planet is under threat of catastrophic collapse, and if we don't begin to acknowledge and solve them, then we will go down."

Solution and protection

Yet as the number of the displaced by failing ecosystems increase, the work for their protection is falling behind. While a political refugee is given some modicum of protection -- the right to shelter and food -- often those who fled their environmentally devastated homeland are seen as mere migrants. When President Obama granted temporary protected status (TPS) to undocumented Haitians living in the United States in the aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti, it was a step in the right direction for human rights. After all, repatriating them back to a living hell would be immoral at best, and at worst, a crime against humanity. But it is but a small step toward addressing pressing needs and legal protection of this growing population.

Many more steps are needed. Policies toward resettlement of the millions of climate refugees should also include addressing issues of reforestation, rehabilitating degraded land and soils, and desalination of low coastal areas. And the International Court of Justice should also step up its efforts to prosecute those responsible for the man-made environmental disasters such as illegal mining, deforestation and dumping of toxic waste.

"One of the marks of a global civilization is the extent to which we begin to conceive of whole-system problems and whole-system responses to those problems," noted political scientist Walt Anderson in his book All Connected Now. "Events occurring in one part of the world are viewed as a matter of concern for the whole world in general and lead to an attempt at collective solutions."

Whether humanity can move toward a global civilization will depend by and large on how it can act collectively to deal with what's arguably the central issue of our time: climate change and resulting human displacement.

There's an old saying, "A rising tide lifts all boats." But in the age of melting glaciers, that tide is an ominous threat. The global age will not be as golden as some had predicted unless this dire challenge is met by whatever means necessary. For rising tides will not just send more refugees fleeing but, if ignored, could swallow humanity itself.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of 'Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora' (Heyday Books, 2005) and 'East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres.' His next book, 'Birds of Paradise Lost,' is due out in 2013.

>

Despite their numbers, and their need, most nations refuse to recognize their status.

The 1951 U.N. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees defines a refugee as a person with a genuine fear of being persecuted for membership in a particular social group or class. The environmental refugee -- not necessarily persecuted, yet necessarily forced to flee -- falls outside this definition.

Not Recognized, Not Counted

Where the forest used to be, torrential rains bring barren hills of mud down on villages. Crops wither in the parched earth. Animals die. Melting glaciers and a rising sea swallow islands and low-lying nations, flooding rice fields with salt water. Factories spew toxic chemicals into rivers and oceans, killing fish and the livelihood of generations.

So people flee. Many become internally displaced, others cross any and all borders in order to survive.

Experts at last year's American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) estimated their numbers would reach 50 million by 2020, due to factors such as agricultural disruption, deforestation, coastal flooding, shoreline erosion, industrial accidents and pollution. Others say the number will triple to 150 million by 2050.

Today, it is believed that the population of environmentally displaced has already far outstripped the number of political refugees worldwide, which according to the United Nation High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) is currently at around 10.2 million.

Still, accurate statistics are hard to come by.

Because the term "environmental refugee" has not been officially recognized, many countries have not bothered to count them, especially if the population is internally displaced. Other countries consider them migrants, and therefore beyond the protection granted refugees.

Another factor obscuring the true scope of the population is the fact that their numbers can rise quite suddenly -- such as after the Fukushima nuclear disaster last year, or Haiti's 2010 earthquake which displaced more than 1 million people -- which makes accounting for their number difficult if not impossible.

In 1999 the International Red Cross put the number of those displaced by environmental disasters at 25 million. In 2009 the UNHCR [United Nation Refugee Agency] estimated that number to be 36 million, 20 million of whom were listed as victims of climate change-related issues.

A "Hidden Crisis" No More

Two decades ago, noted ecologist Norman Myers predicted that humanity was slowly heading toward a "hidden crisis" in which ecosystems would fail to sustain their inhabitants, forcing people off the land to seek shelter elsewhere. After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, however, the crisis became painfully obvious.

As the world watched in awe and horror while hundreds of thousands of displaced Americans scurried across the richest nation on Earth searching for new homes, it became clear that no matter how wealthy or powerful, no country is impervious.

Indeed, being displaced by natural disasters may very well become the central epic of the 21st century. Kiribati, the Maldives and Tuvalu are disappearing as we speak, as the sea level continues to rise. The World Bank estimates that with a 1 meter rise in sea level, Bangladesh would lose close to 20 percent of its land mass, resulting in countless deaths and millions of environmental refugees. Facing present problems of crop failure, destruction of fisheries, loss of biodiversity and flooding, many have already fled to neighboring India, where they endure lives of immense misery and discrimination.

China, in particular, is a hot spot of environmental disasters as it buckles under unsustainable development, giving rise to rapid air pollution and toxic rivers. Alongside desertification, these man-made catastrophes have already left millions displaced.

John Liu, director of the Environmental Education Media Project, spent 25 years in China and witnessed the disasters there. He offered the world this unapologetic, four-alarm warning some years ago: "Every ecosystem on the planet is under threat of catastrophic collapse, and if we don't begin to acknowledge and solve them, then we will go down."

Solution and protection

Yet as the number of the displaced by failing ecosystems increase, the work for their protection is falling behind. While a political refugee is given some modicum of protection -- the right to shelter and food -- often those who fled their environmentally devastated homeland are seen as mere migrants. When President Obama granted temporary protected status (TPS) to undocumented Haitians living in the United States in the aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti, it was a step in the right direction for human rights. After all, repatriating them back to a living hell would be immoral at best, and at worst, a crime against humanity. But it is but a small step toward addressing pressing needs and legal protection of this growing population.

Many more steps are needed. Policies toward resettlement of the millions of climate refugees should also include addressing issues of reforestation, rehabilitating degraded land and soils, and desalination of low coastal areas. And the International Court of Justice should also step up its efforts to prosecute those responsible for the man-made environmental disasters such as illegal mining, deforestation and dumping of toxic waste.

"One of the marks of a global civilization is the extent to which we begin to conceive of whole-system problems and whole-system responses to those problems," noted political scientist Walt Anderson in his book All Connected Now. "Events occurring in one part of the world are viewed as a matter of concern for the whole world in general and lead to an attempt at collective solutions."

Whether humanity can move toward a global civilization will depend by and large on how it can act collectively to deal with what's arguably the central issue of our time: climate change and resulting human displacement.

There's an old saying, "A rising tide lifts all boats." But in the age of melting glaciers, that tide is an ominous threat. The global age will not be as golden as some had predicted unless this dire challenge is met by whatever means necessary. For rising tides will not just send more refugees fleeing but, if ignored, could swallow humanity itself.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of 'Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora' (Heyday Books, 2005) and 'East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres.' His next book, 'Birds of Paradise Lost,' is due out in 2013.

>

Published on August 15, 2012 14:04

•

Tags:

bangladesh, china, climate-change, disasters, earthquake, environment, environmental-refugees, migrants, refugees, sea-level, tsunami, tuvalu, vietnam

The Tragedy of the Internally Displaced: Invisibility and Silence

For every Syrian who escaped the civil war in his or her homeland by crossing international borders, there are three more displaced within the country. Those who manage to leave become refugees. Those who stay behind remain invisible. But they are part of a growing population of refugees that are often without international support, a sub-group of people whose basic needs are rarely addressed by the global community: the internally displaced.

Since the civil war started in April 2011, 2.2 million Syrians have fled across the borders, the majority to Jordan, Lebanon, and Jordan. But according to the USAID there are at least 5 million internally displaced people who failed to do so and are in dire need of humanitarian assistance but largely remain out of international reach.

All who are robbed of home and hearth suffer, of course. But those who escaped the fighting in their homelands by fleeing abroad at least managed to survive, even if they have to subsist in tents and ramshackle huts and depend on charities and donations. Some receive the world's sympathy and media coverage. A rare few even found asylum in the West.

By contrast, those who are internally displaced fare much worse, as they become truly dispossessed. They fail to cross an international demarcation and thereby don't legally qualify as refugees. Instead of receiving international protection and media coverage, many remain invisible and live in constant fear. As in the case of Syria, with the civil restricting international media coverage and assistance, very little protection for IDPs can be had.

A United Nations report "Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement" defines internally displaced persons (IDP) as "persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border."

It is the "natural or human-made disasters" part of the UN definition - which itself is not legally binding - that makes the number difficult to quantify and monitor. Do the millions of roaming Chinese within the country because of industrial pollution that's devastated their agricultural land or displacement by a government building project count as Internally Displace people? And what do we make of Japanese citizens forced out of Fukushima region? How about those who fled from environmental degradation and drought? There is just no easy way to quantify this population of the displaced.

On top of the current news curve is the story of the victims of Haiyan typhoon in the Philippines. Some 800,000 are reportedly homeless, and conditions worsened as many are living without support in hard to reach area. But they at least are garnering world sympathy and news coverage.

Darfur Refugees

For the majority of the displaced population, their stories aren't told, and invisibility is their curse. But their numbers are increasing. According to the UNCHR there are 26.4 million internally displaced people in the world in 2011. But some organizations estimate that the actual number of IDP is easily twice the number of internationally recognized refugees, if not triple that amount. The figure can fluctuate due to the sudden outbreak civil war or a natural disaster such as an erupting volcano, tsunami or earthquake.

Distributions of food and medicine vary from place to place, and IDP protection depends on where they find themselves and which country they are in. Haiti is but a quick jump over from the United States and after the earthquakes in 2010, food and supplies and media coverage came relatively quickly - if chaotically - for earthquake victims. But after years of civil war in Darfur, hundreds of villages have been destroyed, 400,000 have died, and 2.2 million are now permanently displaced and many facing starvation and ongoing violence. It's a humanitarian crisis in which the international response is shockingly slow and ineffectual, and world attention is at best sporadic and the international community falls into what is popularly known compassion fatigue.

It may explain why there's little coverage for the millions displaced in The Democratic Republic of Congo, where 45,000 people continue to die each month, and more than 6 million people have died from long drawn out war and famine? And we know little about the hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingya population in Rakhine state who are robbed of home and hearth due to religious persecution in Buddhist majority Myanmar? Unless they drowned at sea trying to escape the country, as in the case of the 50 refugees last week, their stories remain largely untold. In Iraq, as of the end of 2012, there are 2.1 million people living in protracted displacement, their world unraveled because of the US occupation and inter-ethnic strife. In North Korea, the suffering and starvation of a large number of people remain mostly unknown.

Refugees and IDP are essentially the same. Both groups are coerced or compelled to flee in fear for their lives and security, but those who crossed internationally recognized state borders fall under systematic protection and assistance under existing international treaties, while those who don't are entitled to little, and often garner little international attention.

Pope John Paul II once called the plight of refugees "the greatest tragedy of all human tragedies" and "a shameful wound of our time." In the 21st century, that wound has festered and gangrened. How effectively we as an international society address it will largely determine the future of our global society. For all refugees' plight should challenge our conscience, as silence and indifference constitute the sin of omission.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of three books, "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and his latest, "Birds of Paradise Lost," a collection of short stories about Vietnamese refugees struggling to rebuild their lives in the Bay Area. It recently won the Josephine Miles Literary Award and is now available on Kindle.

Since the civil war started in April 2011, 2.2 million Syrians have fled across the borders, the majority to Jordan, Lebanon, and Jordan. But according to the USAID there are at least 5 million internally displaced people who failed to do so and are in dire need of humanitarian assistance but largely remain out of international reach.

All who are robbed of home and hearth suffer, of course. But those who escaped the fighting in their homelands by fleeing abroad at least managed to survive, even if they have to subsist in tents and ramshackle huts and depend on charities and donations. Some receive the world's sympathy and media coverage. A rare few even found asylum in the West.

By contrast, those who are internally displaced fare much worse, as they become truly dispossessed. They fail to cross an international demarcation and thereby don't legally qualify as refugees. Instead of receiving international protection and media coverage, many remain invisible and live in constant fear. As in the case of Syria, with the civil restricting international media coverage and assistance, very little protection for IDPs can be had.

A United Nations report "Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement" defines internally displaced persons (IDP) as "persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border."

It is the "natural or human-made disasters" part of the UN definition - which itself is not legally binding - that makes the number difficult to quantify and monitor. Do the millions of roaming Chinese within the country because of industrial pollution that's devastated their agricultural land or displacement by a government building project count as Internally Displace people? And what do we make of Japanese citizens forced out of Fukushima region? How about those who fled from environmental degradation and drought? There is just no easy way to quantify this population of the displaced.

On top of the current news curve is the story of the victims of Haiyan typhoon in the Philippines. Some 800,000 are reportedly homeless, and conditions worsened as many are living without support in hard to reach area. But they at least are garnering world sympathy and news coverage.

Darfur Refugees

For the majority of the displaced population, their stories aren't told, and invisibility is their curse. But their numbers are increasing. According to the UNCHR there are 26.4 million internally displaced people in the world in 2011. But some organizations estimate that the actual number of IDP is easily twice the number of internationally recognized refugees, if not triple that amount. The figure can fluctuate due to the sudden outbreak civil war or a natural disaster such as an erupting volcano, tsunami or earthquake.

Distributions of food and medicine vary from place to place, and IDP protection depends on where they find themselves and which country they are in. Haiti is but a quick jump over from the United States and after the earthquakes in 2010, food and supplies and media coverage came relatively quickly - if chaotically - for earthquake victims. But after years of civil war in Darfur, hundreds of villages have been destroyed, 400,000 have died, and 2.2 million are now permanently displaced and many facing starvation and ongoing violence. It's a humanitarian crisis in which the international response is shockingly slow and ineffectual, and world attention is at best sporadic and the international community falls into what is popularly known compassion fatigue.

It may explain why there's little coverage for the millions displaced in The Democratic Republic of Congo, where 45,000 people continue to die each month, and more than 6 million people have died from long drawn out war and famine? And we know little about the hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingya population in Rakhine state who are robbed of home and hearth due to religious persecution in Buddhist majority Myanmar? Unless they drowned at sea trying to escape the country, as in the case of the 50 refugees last week, their stories remain largely untold. In Iraq, as of the end of 2012, there are 2.1 million people living in protracted displacement, their world unraveled because of the US occupation and inter-ethnic strife. In North Korea, the suffering and starvation of a large number of people remain mostly unknown.

Refugees and IDP are essentially the same. Both groups are coerced or compelled to flee in fear for their lives and security, but those who crossed internationally recognized state borders fall under systematic protection and assistance under existing international treaties, while those who don't are entitled to little, and often garner little international attention.

Pope John Paul II once called the plight of refugees "the greatest tragedy of all human tragedies" and "a shameful wound of our time." In the 21st century, that wound has festered and gangrened. How effectively we as an international society address it will largely determine the future of our global society. For all refugees' plight should challenge our conscience, as silence and indifference constitute the sin of omission.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of three books, "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and his latest, "Birds of Paradise Lost," a collection of short stories about Vietnamese refugees struggling to rebuild their lives in the Bay Area. It recently won the Josephine Miles Literary Award and is now available on Kindle.

Published on November 13, 2013 07:55

•

Tags:

climate-change, environment, haiyantyphoon, humanitarian, internally-displaced, invisibility, iraq, philippines, refugees, suffering