Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 22

July 5, 2021

The right words

Due to mini-strokes and constriction of the blood flow in her brain, my mother has developed the same form of cognitive decline that my mother-in-law had: vascular dementia. In both cases, aphasia ravaged their speech as their conditions worsened. My partner’s stepmother also had aphasia due to stroke, so I have now witnessed the condition up close among three women who had very different backgrounds and personalities. As aphasia presents most noticeably as a loss of verbal expression (talk about being at a loss for words!), the condition fascinates me (a person who loves words).

And devastates me. My mother had never been “good at words” the way my father was, but she was a compassionate listener and often could find the right things to say when my glib and witty friends and family members could not. I recall many times when she would ask to talk to me alone and express something she’d been keeping to herself and reflecting upon, waiting until she could “say it the right way.” Now, she can say almost nothing “the right way.” Rain becomes snow; snow becomes green; hat becomes clark; tomato becomes red; table becomes place…and even these are unreliable substitutes, likely to change from one conversation to the next. The pronoun she has vanished from her lexicon. Her vocabulary is little better than a five-year-old’s, and she inadvertently invents words that are essentially meaningless while trying to convey meaning.

She can still read, a little, and slowly. A few months ago, I gave her a book by Eloise Klein Healy, Another Phase. Healy, a well-known poet, was stricken with Wernicke’s aphasia and–with a devoted speech therapist’s help–regained the ability to compose poetry again, though the work she now produces reflects her profoundly-changed expressive abilities. My mother was pleased that she could read the book and that Healy could make poems even with aphasia. And Mom understood the poems–had memorized a few image-lines that she liked. This stunned me–memory’s often wrecked by vascular dementia, or so we are led to believe. But my mother has a good memory. She merely has extremely limited verbal expressiveness–an inability to locate the right word, and a loss of numeracy and literacy. Alas, the result means she cannot make her ideas and thoughts known to others. Isolating.

The pandemic lockdowns at her assisted living campus, my father’s death after 62 years of marriage, her gradual hearing loss, her inability to drive or go shopping–all of these led to further isolation. And isolation, of course, worsens the dementia.

Now that the lockdowns have been lifted, my family members are spending as much time as we can visiting her. One Best Beloved drove her to the church she has been attending by Zoom, now that in-person services have resumed. This past holiday weekend, I picked her up at her apartment and drove her back to my house. Due to my dad’s ill health and the pandemic, it has been over two years since she was here; but for 25 years, she and my father drove here many, many times. It was heartwarming to watch her as she relished returning to a familiar and much-loved place, which also happen to be my house and yard.

She kept saying, “This is so good. This is so, so good!” We’d arranged a mini-gathering for lunch, and there was tasty food and lively conversation all around her. She doesn’t seem to feel frustrated at not being able to join in the dinner chat; I think she was glad just to listen. After awhile, her vocabulary even expanded a bit. She said, “This is fun!” and “This is so great!” in addition to repeating how the day was so good. The joy was palpable.

(I am reading about joy just now, as it happens–a book by Douglas Abrams, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and the Dalai Lama called The Book of Joy. More on that another time, perhaps.)

After lunch, some dessert, and a brief nap, my beloved mom admitted it was probably time for her to return to her apartment. I drove her home, and the ride back was full of comfort and ease and quiet companionship such as I haven’t felt with my mother during the past couple of difficult years, though it’s been there my whole life. I was helping her out of the car when she said, “That was wonderful. Let’s do that again!” Two sentences in perfect grammar, and a boost in vocabulary from good to wonderful.

“Only connect.” I don’t think E.M. Forster was referring to aphasia or to isolation in Howard’s End, but the phrase suits today’s post. Human connection matters. Indeed, it’s wonderful.

June 26, 2021

The berries

It is my custom to pick blackberries in the heat of the day. Perhaps I relish discomfort: the heat, the muggy late-June or early July weather, the thorny canes interspersed with other thorny canes and exuberant vines, poison ivy among these. I always end up scratched, sweaty, sunburned, and itchy; but I end up with blackberries.

Picking at midday means I encounter fewer mosquitoes, for one thing. And in midday I am likely to be the only berry-gatherer in the thickets. Everyone seems to love blackberries and mulberries—which ripen about a week earlier, so these berry seasons overlap. Everyone! Birds, squirrels, deer, foxes, groundhogs, raccoons, possums, bears…

Blackberry fruiting gives way to blueberries, and blueberries to wineberries and elderberries, so that bellies get filled and seeds get dispersed all over the place. I hear rustlings in the hedgerows and at the edge of the woods at night, so yes, I would rather loot my fruit when only “mad dogs and Englishmen” are outside.

Tonight, we’ll have berry cobbler.

I’m still not writing very much new work, but blackberry picking brought to mind this poem from quite some time ago. The poem’s speaker is hiking, not berrying, but I thought of it just the same.

~

Bear & CloudburstBlue Ridge, 4200 feet:we start our ascent, sweetcicely going fast to seedtrailside goldenrod in bloom.Bees hover and hum,we walk one by one by one by onesummer-heat left behindsmothered in pipe vine.Track and blaze. Trail climbsthrough laurel—twisted, dryfrom two years’ drought, skyovercast, color of thin wheybut the ranger doubts rain,has hoped too long, in vain.As we file by, he waves.Further up. Dense shrubsthickets of berries slubbedlike raw silk, leaves daubedwith stippled insect eggsor lichen, fungus, swagsof spider webbing, sacs and bagsand butterflies, brute gnatsundeterred by repellent. We swatstobs, are scratched. The scatalong trailside I recognize as bearbut say nothing, though a fearthreads my ribs tightly whereinstinct thumps. Our feet trampsoil, each step sounds the tampof soles ascending; camp’sfour hundred meters’ altitudebelow. Skeletal crane-fly skeweddry in a web. We walk through woods, a clearing up aheadwhen a pungency atteststo recent presence, and Alice says“There’s a funny smell.”Her voice seems oddly small.We summon our collective will,engage in loud conversation.Bears aren’t known for discussion,are likely to flee in disgust. Then,thunder. Air, though thin,grows humid. Under the dinthe tree-line beginsto go, our path exposedas a blade of lightning explodesahead, just to the north.Pick up the pace. Slouchback to the undergrowth, the touchof brambles like a scutchon skin. We scuff the leavesin the musky, bracing odor, pleasedto be off-summit, our speedfaster than before and louderas we plunge downhill and wonderwhere the bear has wanderedand if it’s found shelter.We’ve half a mile to weatherin the rain. I slip. I’d ratherclimb into some outcropped sweephidden beneath a sweetgum tree,nuzzle the berry-breathed bear, and sleep.June 22, 2021

In which I regress

I was a child who liked mud puddles. Well, mud, generally–but splashing through mud puddles was an especial pleasure. Barefooted in mid-summer at the beach or in the yard; booted other times of year, because I knew better than to wreck my shoes.

Water sends me back. I’m somewhere between the ages of 3 and 11. I am in one of my happy places. A puddle. A puddle in the rain, perhaps.

Of course people, as early humans existing in the marvelous and dangerous world, would infer that water is holy.

~

Splash!

Splash!~

I felt water’s holiness when I was a child. Though perhaps that was a memory of the baptismal font, with me in my father’s grateful embrace.

June 18, 2021

Constricted

I am forcing myself to write despite my sense that the flow, such as it is, has narrowed. I’m keenly aware that there’s a lot of material beyond the blockage and opening the floodgates may be as unmanageable as the “dry period” is unrewarding. Funny thing about balance. Keeping the seesaw level–no easy task. And as my peers and I progress toward aging, the constriction metaphor applies all too well. Many people I know now walk around with plastic or metal tubes inserted in their interiors to keep vital organs ‘flowing.’ My mother’s brain operates through constricted blood vessels, and now she can barely produce an understandable sentence. My lower back’s accumulating calcium deposits that have narrowed the path my spinal cord takes as it does its daily, necessary work.

Sometimes the flow of anything gets constricted. In our bodies. In the earth’s rivers. In our cities and houses: clogging and backups, plumbing and traffic. We implant stents, dig culverts, widen highways, remove the blockage–once we have determined where it is. There’s the challenge. Where is the rub that keeps us from our dreams? (Hamlet couldn’t figure it out, either).

Normally, I read at least a book a week; lately, just magazine articles, or no reading at all. Very strange for me–and I wonder whether my lack of motivation for reading and my current “dry spell” hinge on sorrow. My workplace has been busy lately, lots of scheduling, many meetings and decisions, not much time for personal reflection. It becomes natural, easy, to do the work of routine and ignore the kind of creative effort that grief requires. In my case, there’s also speculative grief: I know my mother’s dying little by little. We who love her spend as much time as we can with her, lifting our own spirits whenever our visits or gifts of chocolate and flowers and dinners out make her happy. What does she love? Fresh strawberries, for example. I bring them from my garden. She savors them. My day is made.

But I come home sad.

vessels, unconstricted

vessels, unconstricted~

I wrote to a friend recently:

My writing practice has suffered a bit during pandemic but feels also as though underlying changes are in process. Just not much by way of results yet.

Somewhat surprised that my father’s death has affected my practice. Or perhaps it is my mother’s aphasia, frailty, and impending death that’s at work here. Or maybe just the stress of trying to maintain my job and relationships with colleagues and students under pandemic protocols, which has not been easy.

My brain’s been stuffed with things like learning new technology and teaching practices, and that leaves less room for wandering and interconnections and daydreaming. And then I have less energy for the creative work, as well. The garden’s been good, though. I’m not discontented, just feeling the currents of interweaving changes.

~

I suppose those interweaving changes may be a bit knotted, if they are threads, or partially dammed, if they are streams. Maybe why that’s the case does not matter much. What matters more is how to proceed when it seems nothing’s forthcoming–patience, force, ritual, practice, or…change.

You can judge your age by the amount of pain you feel when you come in contact with a new idea.

Pearl S. Buck

Wry words from Ms. Buck. Meanwhile, where are those new ideas? Maybe I just don’t feel up to unblocking the flow just yet. A little apprehensive about the pain.

June 4, 2021

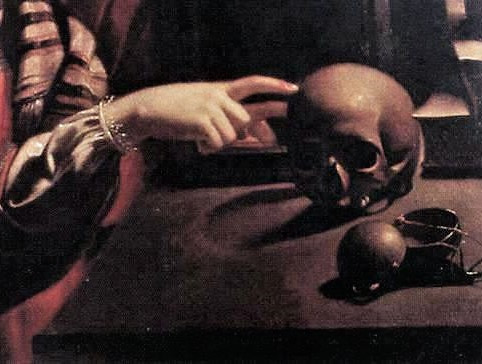

Memento mori

I think I am an amateur naturalist. Maybe my own poetry isn’t so much nature poetry or ecopoetry as it is naturalist poetry. By that I do not mean naturalism as literary criticism defines it–a “movement” belonging to the 19th century. Sean Carroll’s concept of poetic naturalism isn’t quite what I mean, either; Carroll’s approach is more philosophical, though it does get closer to my personal concept. I guess I just mean poetry written by a naturalist.

Such musings arise as I have been reading Bernd Heinrich’s book Life Everlasting: The Animal Way of Death, which offers a naturalist’s low-down on what corporeal death means in terms of the Earth’s environmental cycles; he views every death as a life or as multiple lives–for, in the animal world (which is, after all, our world), a corpse hosts multitudes of new beginnings. It’s simply recycling, the work of millennia. And sometimes the work of Nicrophorus beetles and other “undertakers.” Okay, maybe not a book to every reader’s taste, but fascinating biology. After having read quite a few books on hospice care and human dying, I can now appreciate the amazing biological processes at work in “natural” deaths that work to improve soil, remove waste, feed numerous animals and plants, and regulate the cycle of life. If we want to get ourselves back to the garden, we need to make ourselves more aware of these valuable cleanup crew creatures.

Poets strain experience through words; sometimes we write from the filtered outcome, sometimes we explore the dross that gets caught in the sieve.

A Best Beloved expressed dismay as the news of a friend’s cancer diagnosis coincided with a few recent worries and bereavements: “Everyone’s getting older and falling apart!” But really, what are our options? Die young and leave a good-looking corpse? Live to 100 and die while sleeping? Probably something on the continuum between those poles. Most humans think about, or endeavor not to think about, their deaths and the deaths of those they love. Grief and death are among the Big Themes of poetry, often hovering in the background of a poem that initially appears to be about something else (i.e. Emily Dickinson Emily Dickinson Emily Dickinson  …). Poets strain experience through words; sometimes we write from the filtered outcome, sometimes we explore the dross that gets caught in the sieve. All of it is life.

…). Poets strain experience through words; sometimes we write from the filtered outcome, sometimes we explore the dross that gets caught in the sieve. All of it is life.

“Remember we must die” need not be a call to religious fervor or to pessimistic existentialism. It is merely a fact that we ignore at our peril; for if we remember death is ahead, we can attune ourselves more closely to the lives we do have–and those others with whom we are in relationships. For whether you know it or not, your body has a relationship to Earth and all of its beings. Even, perhaps, the carrion beetle, not to mention billions of microbes and your best friend’s mother.

When I write about death (and I do), I find the tone of the poem depends a great deal on which words or images I use: the clear flow, or the leavings in the sieve. Different purposes, of course. Sometimes the poem wanders in sorrow, sometimes there’s clarity or a lifting of grief. It depends on the perspective (sometimes the speaker of the poem isn’t me), and on where the poem itself decides to go, particularly as I revise. Many readers believe that poems only ever arise from the writer’s experience, but poems are works of the imagination. And they are sometimes informed, or re-formed, by experience or insight that comes later in the writing process.

My own grief? That’s private. I may not decide ever to communicate how that feels. However, having sensed sorrow in my bones and gut and in the empty places in my community of loved ones, I can write about being in the moment of bereavement and the many moments afterwards when the losses make us ache. I like to imagine that memento mori keeps me alert to life. Even when I feel sad.

May 28, 2021

Moon

~

Full moon May

Full moon May~

years agowhen the moon was fullI thought of much to wish fortonight the moonfulfills meMay 26, 2021

Hatching day

After three cloudy, seasonable days–with no rain (we are in a drought)–the temperatures here got up to around 80° F and the cicadas emerged. I took a long walk around campus to observe the hatch.

Judging by the divots in the mulch around the trees, skunks, squirrels, raccoons, and other omnivores had a feast last night. But enough fourth-instar nymphs made it up the trees that I quickly lost count of how many exoskeletons clung abandoned to the bark of pines, maples, rowans, and assorted campus-landscape trees. There were also pale, newly-emergent cicadas–not yet imagoes–most of which were drying out their wings and bodies in the breeze. A few were still in the haemolymph stage (teneral adult stage), which is fascinating. Their wings are still furled, as they haven’t yet inflated with whatever fluid circulates through their systems, and the insects look particularly weird.

Brood X hatches mostly south of us, though this county is right on the border. Definitely seeing more of them this year than I have for many years past.

Magicicada are justly famous for their loudness. There were not many full-fledged adult bugs on campus at noon today; but when I return (on Friday or, perhaps, Tuesday), I expect the place will be buzzing. The students are not here to make the place buzz–I’ll be happy to hear the cicadas.

Teneral adult magicicada. Photo by Shannon Kirby.

Teneral adult magicicada. Photo by Shannon Kirby.I feel as though a haiku might be needed here. Can anyone supply one? I’d be grateful…

May 10, 2021

Perspective(s)

Usually when I spy the red-bellied woodpecker, what I notice is the large red stripe on its…head. Today, the bird was facing me through a nearly-empty birdfeeder, and I perceived the ragged oval of blush-colored down on its underside. I felt a keen admiration for ornithologists who notice such small details. How many times have I seen the red-bellied woodpecker and noticed only its zebra-like striations and its vivid crown? Even those of us who consider ourselves practiced observers of ____ (name your favored area of observation) find we’re not as careful as we imagine we are.

http://www.oiseaux-birds.com/card-red-bellied-woodpecker.html

http://www.oiseaux-birds.com/card-red-bellied-woodpecker.htmlI do not own a powerful telephoto lens for my old digital camera, so I rarely take successful pictures of birds. My noticing tends toward the small and not-fast-moving: flowers, mosses, flora, lichen, fungi, landscapes. I have learned to look mostly at my feet, and occasionally at the clouds. It seems that the limits of my camera and of my vision (terribly, terribly nearsighted) have led to a particular perspective that affects my photos, my botanical interests, and my poetry.

Which is, sometimes, all to the good–but not uniformly. Perspective should be varied; we humans need to imagine that other humans (and non-humans) may witness life from other points of view. This concept is fundamental to psychological understanding and to the much-vaunted and controversial “theory of mind.” It also gives us the pathetic fallacy and anthropomorphism, which expand human ideas about consciousness and offer plangent and resonant metaphors that writers can employ.

All of this came to top of mind today when a student brought in a Philosophy paper concerning Nietzsche’s perspectivism.

Nietzsche opposes philosophers who ignore the fact that individuals have limitations on their theorizing. What makes his idea so thorny is that at the same time he suggests–goes so far as to claim–that perspective (even limited, ideological perspective) is imaginative, is one of our human freedoms. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says:

“Particularly as knowers, let us not be ungrateful toward such resolute reversals of the familiar perspectives and valuations with which the spirit has raged against itself all too long… : to see differently in this way for once, to want to see differently, is no small discipline and preparation of the intellect for its future “objectivity”—the latter understood not as “disinterested contemplation” (which is a non-concept and absurdity), but rather as the capacity to have one’s Pro and Contra in one’s power, and to shift them in and out, so that one knows how to make precisely the difference in perspectives and affective interpretations useful for knowledge.” (GM III, 12)

This famous passage bluntly rejects the idea, dominant in philosophy at least since Plato, that knowledge essentially involves a form of objectivity that penetrates behind all subjective appearances to reveal the way things really are, independently of any point of view whatsoever.

Hence, we do not know and cannot know the kind of “original” knowledge that reveals how things “really are,” since each of us is possessed of a unique perspective essentially unshareable by others. And hence a conundrum for philosophers (and freshman students of Philosophy).

Wait. How did I travel from woodpeckers to perspectivism, by way of poetry? Note: Poetry has a way of doing that kind of traveling.

A quote from Joy Harjo: “It was the spirit of poetry who reached out and found me as I stood there at the doorway between panic and love.” We often stand at that door–and there are other doors–and, as we stand there, the perspective(s) we choose create decision, and purpose, and are colored by an almost journalistic observation or by an almost spiritual calling. It can be either. Both.

The woodpecker--head and neck bright as berries--protects its abdomen pink ovaries, soft underbelly.April 30, 2021

Imagined discourse, new skills

Despite pandemic restrictions, or perhaps because of them, I have been blessed with poetry the past few weeks. I have attended workshops and readings remotely/virtually, and I’ve participated in a few of those as well as giving one in-real-life poetry reading. I signed up to get the Dodge Poetry Festival’s poetry packet & prompts, and those appear daily in my email. Best of all, poems have been showing up in my mind–I started quite a few drafts in April.

Up to my ears in potential manuscripts (I have at least two books I am trying to organize), I’m also waiting rather anxiously to see whether my collection The Red Queen Hypothesis will indeed be published this year as planned. The virus and resulting lockdowns have interfered with so much. The publication of another of my books matters to me, but it remains a small thing in a global perspective, so I try to be patient.

Meanwhile, I thank poet Carol Dorf of Berkeley CA, who has been kind enough to read through one of my manuscripts and offer suggestions. It’s such a necessary step, getting a reader. I recently enjoyed this essay by Alan Shapiro in TriQuarterly, in which the author reflects on his many years of poetry-exchanges (he calls it dialogues) with C.K. Williams. His words reminded me of my friend-in-poetry David Dunn, who was, for close to 20 years, my poetry sounding board, epistolary critic, and nonjudgmental pal who often recognized what I was going for in a poem better than I did. Shapiro says he feels Williams looking over his shoulder as he writes, even after Williams’ death (in 2015). In a section of the essay Shapiro has an imagined (possibly?) conversation with a post-death Williams, conjuring the remarks his friend might have made in life, or after. I have had such dialogues with David, but not recently. It may be time to try again. Or, as Williams told Shapiro before he died, “Find a younger reader.”

As if that were easy.

Anyway, I continue to learn new things, even things I did not feel particularly curious about, such as Zoom teaching [blech!] and Zoom poetry readings and remote workshops and online discourse. Hooray, new skills to practice! Here’s a taped reading in which I read a few poems from Barefoot Girls, The Red Queen Hypothesis, and a couple of newer pieces. I appear at 31:48 on this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HFfeoTOVahQ

Though I think you should also give a listen to the other poets, who are worth hearing. ,

Time to weed the lettuce and spinach rows, time to stoop to smell the lily-of-the-valley. And time to have imagined discourses with my Beloveds.

May brings convollaria into bloom

May brings convollaria into bloom

April 23, 2021

Wary of unity

It’s true that I appreciate a somewhat calmer political/media cycle, in part because I sense slightly lower levels of anxiety from my friends. I love my friends and feel sad when they express fear and exhaustion. The social and environmental messes we humans have made continue, however, as the pandemic stretches on (my region is still in “extremely high risk” covid territory, though most of the people I know personally have been vaccinated). Many of us continue to endure losses of all sorts. Even if the losses are small ones, cumulatively they aggregate, intensified by the spectre of climate change and virus spread and whatever local bogeymen trawl through people’s lives.

In response to the current difficulties, we keep hearing calls for “unity.” One way politicians and community advocates of all stripes and ideologies endeavor to “make nice” is through the concept of unifying people. It sounds like a good thing, to invoke our similarities and our common human bond in order to achieve…[insert goal here].

I’m wary of calls for unity. It’s not that I’m cynical (maybe a little), and I’ve certainly been idealistic in my time; but long experience and lots of stories and histories and my father’s background in how people behave in groups have led to feeling circumspect about unity. It works with people, yes, but it also leads to the worst aspects of tribalism. To the fostering of rigid ideologies. To acts against outliers, to the construct of evil Others. I’ve recently re-read Reinhold Niebuhr’s prescient and insightful Moral Man and Immoral Society, and his analysis of how humans behave individually versus in groups strikes me as relevant today as it was in 1932. My dad studied with Niebuhr during the latter’s last years at Union Theological Seminary and, reading this book, I find I’m reflecting on the ways this philosopher/theologian influenced my then-young father’s views on humanity.

My dad was an optimist, a Pollyanna, a great believer that God loved each human equally and that there exists in each person the promise of Good (because his God is Good). As my dad matured and experienced more of life and a lot of death, injury, backbiting, illness, pain, misery, in-fighting, and scapegoating–even in the Church–he examined more closely the dynamics of people in groups. Here’s where Niebuhr gets it right, as far as I can tell: people in groups suck.

No, he never says that, and perhaps I overstate. People in groups tend toward tribalism, shunning those who differ in opinion, perspective, or other ways. People in groups lean inexorably toward immoral behavior, even when the group is made up of individually moral people. Again and again, under differing social perspectives, Niebuhr demonstrates that unity thwarts diversity even when group intentions are moral. And, all too often, with immoral results.

My dad never really gave up on the idea that people could successfully deal with different perspectives and goals even in the same group, that there were approaches to group dynamics that would produce win-win outcomes or compromises without sore feelings. In this respect, he was an Enlightenment thinker like Locke. Optimistic, as I’ve said, though I suppose there were times he despaired; indeed, I know there were. Perhaps he recited the Serenity Prayer* to himself when he felt powerless to make a difference. Perhaps the way people in groups behave is one of those things we cannot change and must somehow accept.

For myself, I choose diversity. The earth manages its diversity wonderfully, even when human beings thwart it. Milkweed seeds and thistle find their ways into monoculture cornfields. Plants and insects gradually populate the rubble we make.

When circumstances keep me in a tribe-like bubble, I read books and poems that show me other perspectives, other climes, other social cultures, cities, classes, geographies–other histories than my own. I find ways to explore, in person or virtually, artwork and film work, drama, music, and dances from places I may never visit but without which I would be less attuned to the World. To its wonders, which are many. Insert here, instead of a unified goal all people “should” achieve, Whitman’s “Kosmos” or Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty” with its line “All things counter, original, spare, strange;” or, more contemporary, Vievee Francis’ glorious “Another Antipastoral” that states:

Don’t you see? I am shedding my skins. I am a paper hive, a wolf spider,

the creeping ivy, the ache of a birch, a heifer, a doc.

~

The World, that great unity. That global balancing act. That paradox: Outliers and Others being necessary, and Beloved.

Happy Earth Day, a day late.

~~~

* You may be familiar with the Serenity Prayer, which Niebuhr composed.