Avi's Blog, page 5

December 17, 2024

Reading A Christmas Carol Every Christmas

Back in 2019, on this blog, I first answered this question: “You said you read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol every Christmas. Why?”

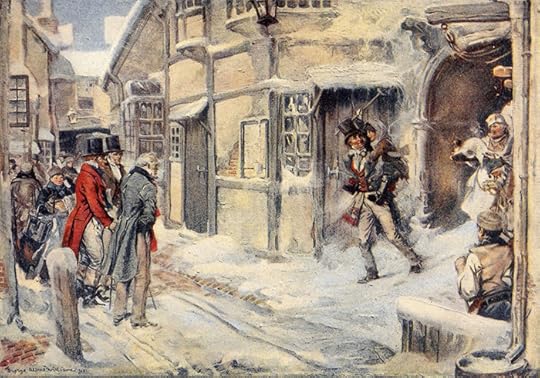

“A Christmas Carol” (public domain)

“A Christmas Carol” (public domain) I have no idea when I first read A Christmas Carol. Perhaps it was read to me. I might have heard it on the radio if you can believe in such ancient times. Many times I have seen the British film, in black and white, with actor Alastair Sim who played Scrooge quite wonderfully. I took my kids to see stage adaptations of the book. I have read the book to my wife a number of times. Indeed, it has been said that the best way to enjoy the book is to read it out loud. I’ll do so this Christmas Eve.

Dickens wrote the book quickly, apparently within a six-week period in 1843 even as he was working on a much larger serial novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, not, in my view, one of his better efforts. As he wrote A Christmas Carol in a frenzy, he described himself alternating between crying and laughing aloud. Still, the first draft was not perfect. The original manuscript is in the Morgan Library (NYC) and, yes, I have looked at it when it’s been put on display there. Here, look at it for yourself (notice the “next” button so you can see the entire manuscript).

When visiting classes, I used to show kids pages from this MS by way of demonstrating that even a writer of genius revises his or her work.

But I note that the opening words, “Marley was dead: to begin with,” were not altered, and I think of that sentence as one of great brilliance.

I think the writing throughout is quite wonderful, so deep and incise in delineating character and place while swerving madly—like a racecar driver on a twisty course—from humor to pathos.

“A Christmas Carol” (public domain)

“A Christmas Carol” (public domain) I admire the construction and pace — a perfect novella — which allows me to read it on a Christmas Eve — the very best time to enjoy it.

When the book was first published, it was an instant and enormous cultural and publishing success. It has never ceased to be. It has been suggested that the book invented modern Christmas.

The most curious thing is — after all these readings and years — it never fails to move me.

Why? Why does it always bring tears to my eyes?

I suspect I feel there is a bit of Scrooge in me—as I suspect there is something of Scrooge in everyone. Accordingly, it reminds me that I regret having done this or that — however small — or maybe big. I connect too — if you have been a child you know it — to the feelings of abandonment that Scrooge as a child experienced.

So, in my experience, A Christmas Carol is ultimately a tale of forgiveness, of redemption, and it is redemption by virtue of giving, the power to make others happier, better — by love.

How could I not need that message? How could I not be moved?

“And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God Bless us, Every One.”

December 10, 2024

The Question of Book Reviews

The question of book reviews is vexing for many writers. Some writers have told me they never read reviews. Others have told me they read them all. Then there are the writers who read selectively, from only certain sources. Over the years editors have told me to ignore reviews, even as others have told me I need to study and learn from them.

Then there is this: Over my years of writing the world of reviewing has changed radically. Whereas many newspapers and journals once reviewed books, these days far, far fewer do. Book sections (and reviewing) in newspapers were once ubiquitous. Many have now disappeared.

Does your local newspaper — if you still have one — review books? Does it matter to you?

Almost simultaneously I heard the head of a publisher’s marketing division say that unless a new book gets three starred reviews, that publisher was not likely to put much effort into promoting it.

That said, a recent book of mine was reviewed by only two professional journals, (both positive) and my editor said I was lucky to get that many.

So the number of book reviews has diminished. Whoever writes these reviews has changed too. Professional reviewing has been reduced, while online reviews, in which regular readers give their personal opinions, have grown far greater in number and have evolved as well.

I have not seen them but I gather book reviewing exists on such as TikTok.

It used to be that reviews truly impacted readership and sales. It is no longer clear if this is so. One wonders, who read reviews? Librarians I suppose. Book store buyers. Readers? Do you read reviews?

Just as social media has changed the way we communicate — not necessarily for the good — online reviewing (which is relatively new) can be much more critical, with anonymity allowing for negative personal remarks. People who write these online reviews are free to say anything, and they do.

Online reviews can also be much more effusive in a positive way. I recently spoke to a voracious reader who said she only reads what’s recommended in online reviews. She pays no mind whatsoever to what any in-print reviewer wrote.

I do read reviews of my books, holding to the notion that I can learn from them. I am also grateful for positive reviews, hoping that they will bring more readers to the book.

I try to mentally screen out personal remarks or quirks and am grateful for the positive reviews. I also try to learn from negative comments. If there is repeated criticism of one aspect of a particular book, I’m willing to believe it’s probably justified.

That said, not long ago a reviewer picked up one of my books (City of Orphans) thinking — because of the title — that it was a dystopian tale. When she discovered that it was nothing of the kind, she wrote a negative review and rated it poorly.

Another recent review, while liking my book (for elementary readers) criticized my failure to give the sociological reasons for aspects of the book.

All this begs the question: what makes for a good book review? What is its purpose? Is it a review of the writer, the writing, or the book? Or all three? Many book reviews are hardly more than a summary of the book. Other reviews are extensive, almost academic discourses on a given book.

Is a review a purely personal response, or should it be put in the context of other similar books? Should the reviewer consider that the writer has spent a year or more laboring over the book? Or is the book, having been made public, fair game for any response?

Should self-published books be reviewed exactly the same way as traditionally-published books? Should a review note that the book was self-published? Is that irrelevant?

Should writers who receive negative reviews be free to review the reviewer? Should a writer ever respond to reviews?

Speaking for myself, I want (and need) to see reader responses to my work. I would like to believe I am still an evolving and viable writer with much to learn.

So, feel free to take a look at what I have written here and — review it.

December 3, 2024

A Book Signing

I may have told this book story here before, but since it happened exactly thirty years ago…

In the spring of 1994, I was informed that I had won the Arizona state award for Nothing but the Truth. Would I come to Phoenix (I think that’s where it was to happen) to accept the award and give a short speech? I was happy to say yes. The date was for early December 1994.

At the time I was living in Providence, Rhode Island.

Shortly after that call, I received another call. Somehow some folks in Colorado learned of this award event and asked if I’d be willing to do a few school visits in the Denver area following my trip to Arizona.

Having an East Coast mentality about geography, I said yes.

Sometime after that call came yet another call from the manager of a children’s bookstore in Denver (where I had never been). The caller knew about my Denver school visits and asked if I’d do a signing at the bookstore, some place called The Bookies.

Sure.

Once I had flight arrangements set, the bookstore manager would pick me up at Stapleton Airport, I’d do the signing, then I’d be taken to my school-designated hotel.

All good. Arrangements were made and the information was passed on to all the necessary parties.

Some six months later, on December 4, I arrived at the old Denver airport. No one was there to meet me. Such things happen. So I went out to the curb and waited. I waited for about an hour.

Not knowing what else to do, I called the bookstore and reached the manager. She apologized and explained she was new on the job. The old manager (the one who set up the visit) had left, and this new one hadn’t been told I was to be picked up. She would come right out to get me.

Another forty minutes passed before a battered Grand Cherokee pulled up. A skinny lady wearing a kilt popped out of the car. “Are you Avi?”

“I am.”

“Sorry about all this. I’m just two weeks into being the store manager and I had very little information about your visit. I’ll get you where you need to be.”

I got in and we started up. After a short while, she turned to me and said, “What were you going to be doing at the store?”

“A book signing.”

“Oh. I wasn’t told that, either. In fact, I don’t know anything about signings. My last job was at IBM. They didn’t have authors coming there.”

Indeed, it soon became apparent that nothing had been done to set up the signing, much less publicize it. The only kids that were in The Bookies that afternoon were the new manager’s two kids. That meant there was nothing for me to do in this essentially deserted store other than to talk to this new manager.

Happily (Linda was her name) was smart, interesting, and a very good conversationalist. I think we talked for two hours, at least. In fact, I was quite smitten with her.

The next day I made my first school visit. As it happened, some of Linda’s kids were students at the school. I noticed that she was there.

I kept thinking about her.

That next day, when I finished up at yet another school and was back at my hotel, I called the bookstore, reached Linda, and asked her to have dinner with me the next night.

She agreed.

We did have dinner and had a lot more talk. She brought me back to the hotel. We said good night, and I went to my room. She left.

As it happened, she decided she wanted to talk some more and went back to the hotel. At the check-in counter, she asked if she could speak to “Avi.”

“I have no guest with that name,” said the clerk “What’s his last name?”

Linda looked at him. “I have no idea.”

Resourceful, she grabbed the guest sign-in book, went down the list of names, found my last name, and called me. “Would you like to talk some more?”

So we did.

Was it love at first sight? Well, maybe second. Reader, the key point is that I married her.

The thirtieth anniversary of our first meeting is coming up.

Best book signing I ever did.

November 26, 2024

Thankful

One of the particular joys of writing for kids is that they write to you. Some, to be sure, are teacher / school assignments, but that doesn’t reduce their own young voices. Then there is the young reader who has felt a particular connection to me and one of my books and shares self and point of view in a very personal manner.

The envelopes that contain their letters are often fancifully decorated, along with messages on the outside. “Read me!” “Open me!” “Write back PLEASE!”

Depending on the handwriting, if it is handwritten, I often can guess the age of my reader.

It’s pretty rare, but now and again the young writer will tell me that he or she did not like a book. I’m interested and appreciative of those thoughts too.

And then there are questions. Everything from how old I am to why do I write books. Where do I get my ideas? How long does it take to write a book? Which is my favorite of my own books? Which is my favorite of all books? And on and on.

There are those letters that tell me I have changed their lives, or their ideas, or feelings about reading. There are those who tell me that they just enjoyed my book.

I answer every letter and try to answer their questions.

And then there are the letters from people who were once kids. Adults who now remember a particular book. Or they share a particular book with their own children. There are the librarians and teachers who have shared my books for many years with their students.

The point of all this is that I am nothing without my readers. To speak metaphorically, my book is one hand, the reader is another, and when they come together there is a joyful noise. It’s not applause. It is the sound of a human connection found in one of my stories.

How thankful I am for all of that.

Avi

November 19, 2024

Lemony Tomato Soup

It was two days after the election, and I was feeling gloomy. Moreover, it had — unexpectedly — started to snow, so the gloominess intensified. Here, at 9,000 feet up in the Rocky Mountains, you take snow seriously.

In any case, I turned back to my current book project, and started a read-through, wanting to be sure my complex story was logical so that it would be easy for my readers to follow.

[See my October 22, 2024, blog post about logic to understand what was in my mind.]

Before I knew it, I had passed midday, and I was hungry. But it (and I) were still gloomy. What to do? Into my mind popped a recipe for Tomato Soup that my wife (and I) love. Perfect for a dull day and easy to make.

I won’t — at this point — share my new book. But I am happy to share the recipe, slightly adapted. It’s called “Lemony Tomato Soup,” from the cookbook, Lemon Zest, by Lori Longbotham.

INGREDIENTS

2 tablespoons butter

1 large onion, chopped

I good squeeze of lemongrass paste

zest from one lemon

28 oz canned whole tomatoes

1 tablespoon dried basil

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon ground black pepper

The freshly squeezed juice of that lemon above

ground Parmesan cheese

INSTRUCTIONS

Melt butter in panCook chopped onion in butter till soft.Add tomatoes and crush themAdd 1 cup of water. Zest. Basil. Lemon grass paste. Pepper. Salt.Simmer for 15 minutes.Put all in a blender. Add lemon juice.Serve hot with Parmesan cheese on top.Was it good? By the time we had our soup lunch, it had stopped snowing, and the sun was shining brightly. What other proof can you ask for? In other words, at that point the soup was a lot better than my new book.

Enjoy (the soup).

November 12, 2024

A Curious Contradiction

There is a curious contradiction that comes from writing for so many years: The more books I begin, the worse they seem at the start. I kid you not, there is almost a feeling of agony when I review the first drafts of a new novel:

This is awful. You’ve lost it. You need to start something else. No one will take this. No one will read this. What made you think this would work?

These are real thoughts — I’ve had them all — as I plunge into the long process of creating a new book. The irony is that these thoughts are not just accurate, they come about because I know good writing when I read it. Early drafts are always bad writing. They are painful to read.

As I have written in these posts many times, the process of good writing is such that the time of creation is long, the effort is arduous, and the process is one of endlessly nitpicking and revising. It can even be boring.

The key point is that it takes a lot of time to write something good. It must evolve. That evolution is also a lesson that I have to teach myself over and over again. The work is bad before it can become good.

Accept it and push on.

The nicest moment comes when, after a great deal of work, I suddenly — and it is often sudden — gain a sense that things are falling into shape. That the work is becoming good.

All of this is because one of the most difficult aspects of writing is the author’s ability to objectively see and be critical of one’s own work. It’s why folks like me so much appreciate a good editor. In truth, there are many editors in my life. You can begin with my wife who is as sharp as she is outspoken. She does not stint, either with the positive or with the negative.

[The worst kind of response — true story — comes from the person who reads fifty pages over an hour and then puts the work down.

Me: Well, what do you think?

Reader: There is a dangling participle in the first paragraph.]

But I have a couple of trusted friends — who are willing to read what I have written and who will tell me what they think. Invaluable.

And finally — most importantly — my professional editor. Your relationship with that person, a matter of deep trust, is key to what you will eventually produce.

All of this goes far to explain why I can say that I have absolutely no objection to self-published work. Equally, I object strongly against self-edited work.

It is a myth that the author creates a book on his or her own.

All of these thoughts come about because I have started a new book. And it’s bad.

That gives me hope.

November 5, 2024

Yes, Foxes Are Sly, But They’re Not Always Sly

I was talking to a sixth-grade class the other day when one of the students asked: “How do you make a character in a book, you know, all the different things and feelings she has?”

That’s a vital question! It’s really good because there is no one answer. My guess is if you ask ten different writers that question, you’ll get ten different answers. Here are a few I’ve learned about.

One of the basic ways to create a character is not to create one but base the fictional person on someone you know well in real life. Mind, no matter how well you do it, it will not be that person, but someone like that person. Also, be cautious, if the real person you are depicting comes across your portrayal, they may not appreciate it.[Years ago, I published a book in which there was a nasty character. A friend of mine decided the character was him and was deeply offended. Actually, I had never given that friend a moment’s thought when I was writing the book. Still, it meant the end of the friendship — his choice.]

Some writers have told me they invent a whole biography of a character, before setting down his/her adventures. Where, when, circumstances of birth, and so forth. Almost like writing another book.You have briefly seen or met someone, and you borrow (as it were) the person’s physical characteristics, and let the character’s physicality determine who and what they do. The way the person dresses, way of talking, and acting can be helpful here. The character of Bear in Crispin, The Cross of Lead, is based on someone I met but did not really know. But his physical presence was quite impactful.

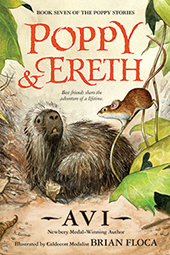

You can evoke a historical personage and work that character into your story in such a way that what is known about him/her shapes your character and story. My most recent book, Lost in the Empire City, has a real person in it, Lieutenant Becker of the New York City Police. He was, no question, a crooked cop, being the only NYPD officer to be executed for murder. But from what I read about him, he was not just a ruthless man, he was also considered quite charming. Curiously, how you name a character can influence how you write about him/her. Names, consciously, or unconsciously, carry emotional weight which is quite individual. It’s not unusual for me to change a character’s name until it feels right. I won’t even presume to understand that, but it does happen, and work. If you are writing about an animal character, learning the biological facts about the creature can often suggest character traits. But beware of clichés. Yes, foxes are sly, but they are not always sly.

You can evoke a historical personage and work that character into your story in such a way that what is known about him/her shapes your character and story. My most recent book, Lost in the Empire City, has a real person in it, Lieutenant Becker of the New York City Police. He was, no question, a crooked cop, being the only NYPD officer to be executed for murder. But from what I read about him, he was not just a ruthless man, he was also considered quite charming. Curiously, how you name a character can influence how you write about him/her. Names, consciously, or unconsciously, carry emotional weight which is quite individual. It’s not unusual for me to change a character’s name until it feels right. I won’t even presume to understand that, but it does happen, and work. If you are writing about an animal character, learning the biological facts about the creature can often suggest character traits. But beware of clichés. Yes, foxes are sly, but they are not always sly.  illustration © Brian Floca, from Poppy and Ereth, written by Avi, published by HarperCollins Someone tells you a story about someone they knew, an odd uncle, a wild office mate, a curious student, a singular teacher they once had — all of them quirky in one way or another, but upon which you can base your character in fiction. Speaking for myself, my characters mostly emerge in the process of the many rewrites I do. I equate such a methodology as learning about a person I just met. It is only when I come to know them in the evolving context of a story (as in life), do I learn about their traits, whims, and how they deal with real events. Be warned, this method requires a lot of rewriting.

illustration © Brian Floca, from Poppy and Ereth, written by Avi, published by HarperCollins Someone tells you a story about someone they knew, an odd uncle, a wild office mate, a curious student, a singular teacher they once had — all of them quirky in one way or another, but upon which you can base your character in fiction. Speaking for myself, my characters mostly emerge in the process of the many rewrites I do. I equate such a methodology as learning about a person I just met. It is only when I come to know them in the evolving context of a story (as in life), do I learn about their traits, whims, and how they deal with real events. Be warned, this method requires a lot of rewriting. Having said all that it is certainly a truism of great books: great characters make great books.

But the deeper and harder truth is, creating a memorable fictional character is brought about by the writer’s knowledge, conscious and unconscious, of people, in all their bewildering and adorable complexity.

October 29, 2024

A New Book

Today is the day my newest book, Lost in the Empire City, will be published. People often ask me, “How does it feel to have a book published?”

Strictly speaking, there are many key dates in the creation of a published book. One might well ask how I feel about any one of them.

Day One. When I commit myself to writing a specific book.Feelings: Excitement and anxiety.

Day Two. When I finish the final draft of that book.Feelings: Relief tinged with sadness. I’ll miss the characters.

Day Three. When — and if — a publisher accepts the book.Feelings: Joy.

Day Four. When word comes from the editor that the book is considered done, or “complete” in publishing jargon.Feelings: Satisfaction.

Day Five. When the first published pass of the book is sent to me for copyright review. That is, I see the book in print for the first time.Feelings: curiosity and delight.

Day Six. When I receive a copy of the published book, which is usually about a month ahead of the official publication.Feelings: Pleasure.

Day Seven. When I get the first review of the book, which is a portent as to how the book will be received.Feelings: Depends on the review.

Day Eight. The official date of publication.Feelings: Pleasure. Another book done.

Seven key days, to be sure, but they can be strung out over a long period, sometimes two or more years. The fastest time I ever had a book published—from day one to day seven, was Night Journeys, with an elapsed time of just eleven months. The longest time was fourteen years, for Bright Shadow.

Let it also be said that by the time I reach day seven, I am usually deep into creating another book. Indeed, my next book has already been written and it has been declared “completed.” Chasing Rocks, as it is titled, is scheduled to be published in early 2026.

So it goes.

The days — as cited here — which are most emotional for me—in a positive way—come when I have completed a book, and when I learn that it will be published.

The days — as cited here — which are most emotional for me—in a positive way—come when I have completed a book, and when I learn that it will be published.

The actual date of publication surely gives me pleasure, but nothing happens with me on that date. Yes, that is the date when it is put on sale, but I am not part of the process.

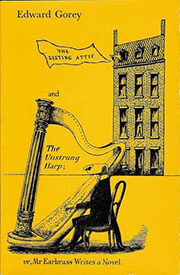

My favorite depiction of the writing life—and publication day is brilliantly and hilariously captured by Edward Gorey’s The Unstrung Harp.

It has more truth about the writer’s life than any other book I know.

October 22, 2024

Logic

The word logic appears to be a Middle English word borrowed from the French language, but only introduced into the written English language in 1362 by the English writer William Langland. It was he who wrote Piers Plowman, a foundational English poem from Chaucer’s time.

The word logic appears to be a Middle English word borrowed from the French language, but only introduced into the written English language in 1362 by the English writer William Langland. It was he who wrote Piers Plowman, a foundational English poem from Chaucer’s time.

A functional definition of logic may be “reasoning according to strict principles of validity.”

And while we may not think of the concept as having anything to do with fiction, it is not just a key aspect of narrative, but particularly important to readers.

Consider the last novel you read: did the story unfold in such a way that it was believable?

Did the events move from one to another in a fashion that you thought made sense? Was it all credible?

I can recall the writer (and my old friend) the late Bob Cormier telling me that “we are allowed only one coincidence per plot.” On the other hand, I take heart with the notion that “Coincidences are God’s little miracles.”

As I compose a new book — as I am now doing — I am constantly asking myself what should (can) happen next? Do the events, actions, revelation, characters, etc., flow logically from what I have already written? In fact, it is not unusual for me to backtrack in my revisions to introduce something into the story at the beginning, so as to allow something else to happen (logically) down the road, so to speak. The reader (hopefully) does not notice.

[Thus, in a book I had recently finished — a tale in the wilderness — it occurred to me belatedly that I neglected to supply my characters with water to drink. Back into the text I went and no longer found myself up a creek, so to speak.

Fine writers create stories with deep logic, bringing about revelations, and new kinds of truth.

On the other hand, if there is no inherent logic in what happens, the reader may (and often does) feel cheated.

It’s relatively easy to see how this works in a mystery, or detective fiction. Here, in a curious way, the logic is deliberately hidden, or made obscure, in the service of the puzzle. But at the same time, when the logic of the deduction is revealed, one wants the reader to say “Of course!”

And there are novels (romance) which, as it were, require a happy ending, and even then, one wants to create (hopefully) logic to make it so.

Comedy creates its own logical problem. Much depends on surprise, twists, the unexpected, but here again it needs to make sense—logic.

I’m not suggesting that writers are philosophers, only that they should think philosophically. Because I do think good writing creates understanding (logic) out of the chaos of life.

QED.

(Latin abbreviation for quod erat demonstrandum: “Which was to be demonstrated.” Q.E.D. may appear at the conclusion of a text to signify that the author’s overall argument has just been proven.)

October 15, 2024

Titles

What does a good title have that makes it good? Lots of notions here. It should encapsulate the story itself. It should suggest what the story is about. It should intrigue the potential reader. It should provide some strong or poetic statement. It may also be said the title is the first salvo of a marketing campaign. The truth is, as any author will tell you, a good title is hard to compose.

In my experience. a title can stay with a book all during its composition. Or it can change often, even as the book evolves.

Perhaps my favorite title shift is The Sea Cook to Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson. Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice had the working title, First Impressions. The Great Gatsby was originally titled Timalchio in West Egg. [Check Google if you want to find out who Timalchio was.] Then there was Orwell’s 1984, and its earlier title, Last Man in Europe.

To be fair, those earlier titles seem odd (or wrong) because we know the books with their final titles so well.

But from personal experience, title changes can happen for many reasons. Sometimes the working title — you discover — has been used for another book. That was the case for my Poppy which had been called Pip.

Turned out there was a book titled Pip: The Story of a Mouse. When I changed the title, I, of course, also had to change the main character’s name.

Something Upstairs got its title when I read the first (unpublished) chapters to a class of fifth graders. At the time it had no title. I asked the kids for a suggestion. A girl raised her hand. “Call it Something Upstairs,” she said.

Done.

My Wolf Rider title doesn’t work because it refers to an obscure line buried in the text. Readers rarely find it.

Sometimes a shift happens because the book itself changes. Thus, The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle was first called The Seahawk, the name of the ship on which all the action takes place. But of course, the novel is far less about the ship, than about the main character, Charlotte. Thus, The Secret School’s working title was simply Ida.

It took a while to give Secret Sisters a title. For a while, I simply called it Secret Sequel.

I used the legal term Discovery, for Nothing but the Truth, but changed it for what I came to think was a clearer, better title.

My original title for Crispin: The Cross of Lead, was No Name. In that case, it was the editor who felt a change was necessary, not an unusual occurrence. I always preferred the original name.

Catch You Later, Traitor was first called Season of Suspicion. But the book shifted publishers and got a new title. One of my sons suggested it should be called just Later.

A title change can occur when the publisher’s marketing team weighs in, but the author hears about that only indirectly. Such was the case when my recently published City of Magic, lost its original title, Midnight in Another World.

My newest book Lost in the Empire City had the title The Four Million and Me. The number refers to the population of New York City in 1911, the time of the story. It’s also an obscure reference to the short story writer, O Henry, who wrote a book about NYC called The Three Million. The new title has much more energy.

So, it goes …

Now I have to give a title for this short essay. Let’s just call it Titles.

Does that work?

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers