Avi's Blog, page 3

May 6, 2025

Frankenstein Books

I was recently at a rare book fair, which was quite fascinating. People, for a great variety of reasons, wish to own first editions of books. A mix of compulsion, obsession, and, to be sure, a great love of books, was on display.

Years ago, I embarked upon a search for old children’s books, haunting flea markets on an almost weekly basis. The books I found — and I found more than three thousand — were never expensive, never more than one or two dollars. This was before children’s books became collectible.

At any rate, at some point, I stopped searching for them and simultaneously had no place to keep them. In the end, I gave them all to the library at the University of Connecticut, which was building a research collection of children’s books. They are still there.

But the books and ephemera at this fair were about a different world. I am not sure I would be willing to pay $250,000.00 for the first edition (with mint dust jacket) for Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby but apparently, there are people who can, and will make such a purchase. A letter written by George Washington (the ink faded) could be bought for $15,000.

But the books and ephemera at this fair were about a different world. I am not sure I would be willing to pay $250,000.00 for the first edition (with mint dust jacket) for Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby but apparently, there are people who can, and will make such a purchase. A letter written by George Washington (the ink faded) could be bought for $15,000.

And I was fascinated by the man who was a lawyer by day, but a major collector of Mark Twain books, and the memorabilia that pertained to the TV series Star Trek.

I did learn that people who collect books are full of stories about books. It was great fun to hear them.

I also sat in on a panel discussion titled, “The Dark Side of Book Collecting.” This was a talk by four collectors that dealt with book thefts, forgeries, and fakeries of all kinds in this rare book collecting world. I found it quite fascinating. It was like listening to four detectives talk about their favorite cases.

My favorite part of the discussion was about “Frankenstein Books,” a term I had never heard before.

What are “Frankenstein Books?” These are books that have been altered, marked, notated, restitched, or mutilated by their owners, not with evil intent, but just the opposite, with excessive love. It might be a book with notes in the margin, as in “I love this passage,” or “This statement is terribly wrong.” It might be a book that was converted into a scrapbook. In my collecting days, I used to find books that contained pressed flowers or four-leaf clovers. Unusual bookmarkers. Or even letters. All these Frankenstein Books reveal something, not so much about the books, but the people who owned them.

My own favorite Frankenstein Book was a 19th-century children’s book I once found that contained two short stories. One was about a young woman who marries a poor man, and the consequences of that marriage. The other story was about another young lady who marries a rich man and the consequences of that marriage.

But—on the flyleaf of that book was a handwritten message. As I remember it read something like:

“Dear Molly,

By the time you are old enough to read this book, I will have been long gone. But when you read this book, I hope you follow the wise advice my favorite story offers. I did.

Your Loving Grandmother…..”

But “Grandmother” never indicated which story was to be followed.

April 29, 2025

Detective Fiction

Right next to the Denver, Colorado neighborhood where I spend winters — escaping the snow that buries our mountain home — there is an unusual bookstore. Rather small and not too well lit, with steep stairways, the Park Hill Bookstore advertises itself as “Denver’s Oldest Non-profit Bookstore.” It’s run entirely by volunteers, and its whole inventory of books is donated by the community. All kinds of books are to be found there. Arranged by category, there are novels, cookbooks, children’s books, titles about Colorado and the West, biographies, and so forth. It’s open six days a week.

I, like many others, am a member, which means I pay a modest annual fee. That allows me, on any given Friday, to bring in a few volumes I no longer want. In return, I am given credit, which allows me to pick a few books of my own choosing. If they are not rare books or don’t have some notable aspect to them, my choices are free. Today I brought in three books and brought one home, a soup cookbook.

The neighborhood is called Park Hill, which, to my eyes, is an upscale, middle-class neighborhood, with attractive architecture, trees, coffee shops, and the normal variety of shops you might expect to find in such an area. It seems very peaceful.

There are always kids about, on their own or with, I presume, parents. Indeed, the Park Hill Elementary School, with its hundred-year-old building, is one of the nicest schools I’ve ever visited. I love going there. The teachers are relaxed and happy. So are the kids.

In short, Park Hill always strikes me as a nice, peaceful community. However, since all the books in the bookstore must reflect the reading habits and interests of its local citizens — remember, they are all donated — it fascinates me that the largest category of books to be found there is mystery and detective fiction. Crime.

The Oxford Unabridged Dictionary tells us that the first use of the English word “detective” appears (in 1843) in something called the Chamber’s Journal. To quote: “Intelligent men have been recently selected to form a body called the ‘detective police’ … at times, the detective policeman attires himself in the dress of ordinary individuals.”

Note “intelligent.” And “ordinary individuals.”

There is a history of crime fiction. Depending on how you define it, there are some fairly ancient examples. That said, English-language detective literature — as a genre — is considered to have begun in 1841 with the American publication of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” There you will find the first fictional detective, the brilliant Auguste Dupin.

The most famous fictional detective is, of course, Sherlock Holmes, given to us by the British writer Conan Doyle in 1887, with A Study in Scarlet.

There are many kinds of detective fiction: cozy, noir, procedural, historical, and children’s mysteries. The list goes on. Indeed, I’ve written a few myself. My first novel, No More Magic, is a mystery. So is Midnight Magic. My favorite is Catch You Later, Traitor. The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle came about because I wrote The Man Who Was Poe.

But my question today is, why is this form of fiction so widely popular? It’s read by an extraordinary range of people. It’s said that two billion copies of Agatha Christie books have been sold! What emotional, intellectual need does detective fiction satisfy?

You can find a variety of answers to that question. I won’t presume to offer a definitive response. My own favorite notion is that the crime is usually depicted as cruel, chaotic, and on the surface, illogical, and therefore in need of solving and controlling. The notion that this can be done by rational, non-violent thought is deeply reassuring to “intelligent, ordinary individuals.”

Consider our times. Chaotic, cruel, illogical, violent.

Is Sherlock Holmes running for office? He’d get my vote.

April 22, 2025

Writers and Their Income

There is a very old joke about writers.

“What’s the difference between a large pizza and a writer?”

“With a pizza, you can feed a family of four.”

I don’t know when I first heard that gag, but it comes to mind at least twice a year. That’s when, in April and October, I am paid the royalties for my books. That is to say, in the middle of those months, I learn what half my income for the year is. It’s based on the sales of my books over the previous six months.

Mind, there are complex equations as to how that amount is figured; there are different percentages of royalties paid for hardbacks, paperbacks, e‑books, audio books, foreign sales, and a host of other variations and classifications. Each category pays a different royalty percentage.

The crucial point is, I am never sure what the total amount will be. My income is always changing.

[If an author wishes to dispute the amount, he/she can audit the publisher’s accounting, but the writer must pay for that audit. I once learned of someone who made a business of auditing publishers’ accounts, so there must be a fair number of writers who do so. I never have.]

There have been times I have been surprised by the royalty paid me. Sometimes that is because the royalties are more than I had anticipated. Sometimes it has been less.

The total payment pertains to all of the books I have published that remain in print, from the oldest to the newest. Thus, in my most recent royalty payment, my very first book, Things That Sometimes Happen, which was first published in 1970, just earned me a royalty of $5.16. After fifty-five years, it amazes me that it is still around.

There is a key factor in all this that must be further understood. When a book of mine is accepted for publication, I am paid an advance, that is, a negotiated (by my publisher and my agent) fee based on the royalty that the book is projected to earn. This money is actually a loan to me. It is meant to allow me to live while I write the book. That has sometimes been the true case. However, the further point is that I do not get paid a royalty until I pay back that advance, and I do that with the sales of the book. If the sale of a book goes well, that advance is paid back quickly, and I start to earn royalties. Best-sellers are good. Awards help. So do review stars.

If sales are slow, it may take much longer to earn royalties. There have been very few books of mine that have never paid back the advance. Still, to this moment, I have never earned royalties for those books.

Furthermore, with newly published books, it takes time to earn back that advance. I don’t recall ever paying back that advance in the first six months of publication. So, at best, it will be at least a year after the publication of a particular book that I will begin to earn royalties.

To be fair, if the book does not ever pay back that advance, it is understood that I do not have to pay back that advance [loan] out of pocket.

Let me be very clear that for many years, I have made a decent living as a writer. Yes, there have been fat years and there have been lean years. But I have never been forced to apply for a job as a pizza maker.

April 15, 2025

Reading It Again

To be sure, it was only a coincidence, but the week of March 7th — the week of the recent financial chaos — was also the week that marked the one-hundredth anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Towards the end of the book, Nick Carraway, the book’s narrator says: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

To be sure, it was only a coincidence, but the week of March 7th — the week of the recent financial chaos — was also the week that marked the one-hundredth anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Towards the end of the book, Nick Carraway, the book’s narrator says: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

That seemed very much like a summary of the financial chaos, and its cause. I do wonder who will clean up the current mess.

Reading about The Great Gatsby made me think of another American classic, Moby Dick, by Herman Melville. What is the connection? Captain Ahab, like Gatsby, is also driven to achieve the unattainable — the killing of the great white whale — and in that pursuit also wreaks havoc and destruction.

Reading about The Great Gatsby made me think of another American classic, Moby Dick, by Herman Melville. What is the connection? Captain Ahab, like Gatsby, is also driven to achieve the unattainable — the killing of the great white whale — and in that pursuit also wreaks havoc and destruction.

That these two novels, so utterly different — both real contenders for “The Great American Novel” — should touch on such similar themes struck me. It suggests that the pursuit of the American dream — that one can achieve anything if only one tries — carries the seeds of self-destruction.

The books shared another similarity. When first published, both books were negated by critics, only to be resurrected — after their authors died — as great works of literature. That meant that neither author had any notion how their books would come to be revered.

Did both die thinking themselves failures?

One critic I read — reflecting on The Great Gatsby — comments on how modern a story it is with issues of race, sex, money, greed, addiction, and the general excessive aspects of our lives. Yet, the same critic interestingly suggested that the book is one of our cultural unifiers, in so far as it holds its niche as an almost universal high school reading requirement. I cannot imagine how young people today relate to the book.

I think I’ve read the book four different times in my life, and each reading brings forth a different reaction. I don’t know when I first read it. Perhaps it was in high school, and I don’t fully recall my reaction other than I liked it. But a few years ago, I read it for the third time and was put off by its flamboyant language and syntax. This time — the fourth time — I was taken by how modern it all was, how relevant for today. As for the diction — if you will — it was all one with the wild world the novel depicts. I took pleasure in it.

[One definition of great works of art is that such creations are always relevant to the time they’re being first experienced, not just the time when they were created.]

Fitzgerald himself had a complex life, early wild success, a tragic marriage, a decline into Hollywood alcoholism, and then posthumous fame. A different kind of “American dream.” Or maybe nightmare.

Regardless, it’s all there in The Great Gatsby.

April 8, 2025

Getting a Book Out of My Hands and Into Yours

We go to a library or a bookstore — or maybe even a Little Free Library — and select a book. We take it home, settle into a favorite chair, and turn to the first page. It all seems straightforward and simple. It’s not.

[Note: As you read this, always keep in mind that I love what I do and have been doing it for more than fifty years.]

A number of years ago, a publisher suggested to me that it took about forty people to produce a book. Today, that could be more or less. I have no idea. Most of the book production is by people I never talk to, know, or meet. I do know — as a writer of books — that I am only one of many creators, and the time it takes to get the book into your hands is many months.

It takes me — sometimes longer, sometimes shorter — about a year to write the first draft of a novel. Along the way, there are endless fits, starts, stops, and, if you will, goes. I rewrite endlessly. My wife tells me she knows when my writing is going well by the rapidity of computer key clicks she hears. I’m not so sure. Sometimes, slow is good, too.

When I feel the book is whole (NOT done) I read the book to my wife, pen in hand. Aside from hearing lots of glitches, she — a fine critic — is not shy about telling me what is strong and weak. I pay attention and usually act accordingly.

Then, further along, I have a school where — for years — I have read my early draft books to an appropriately-aged class. I watch and listen to their responses, check with the teacher to get off-class time comments.

There are rewards. When I recently finished reading a new book to a fourth grade class, a boy came up to me and said, “Can I give you a hug?” When he did, he whispered, “Write a sequel.”

If that’s not a * review, I don’t know what is.

Then, I may share the book with friends and colleagues. My forthcoming book — The Road from Nowhere — which is set in an 1890’s Colorado mining camp, was shared with my writer friend Will Hobbs, who has written so wonderfully and knowledgeably about the American West. He knew, given the location of my story, where silver would most likely be smelted. I had it wrong. He set me right.

The book is sent to my agent, who reacts, and I act accordingly. Only then is the work submitted to an editor. Because I have published with so many publishers, this is not an automatic choice.

The book may be accepted by publisher A or rejected. If rejected, it goes on to publisher B. Or C …

Then, if the book is (tentatively) accepted, there is often a discussion as to the strengths and weaknesses of the story. “Would you be willing to rewrite this or that section?” “Are you open to strengthening the ending?”

Yes, no, until agreement is reached.

Simple? No. Not too long ago an editor accepted a book and told me a contract would be forthcoming. And would be. And would be. And would be. For six months. Except it wasn’t forthcoming. A new divisional chief said, “No.”

However, assuming real acceptance, a contract is drawn up. This, too, can take a while.

But since a commitment has been made, the editor and I begin to revise the book. It usually starts with the editor’s editorial letter, which outlines all those places (mostly) big, some small, that will strengthen the book.

I revise. The editor reads. Makes more suggestions. I revise. Back and forth. (I think Crispin’s opening pages were rewritten at least twenty times.)

This goes on until the editor (not me) says, “I think we’re done.” But, knowing we are never truly done, I keep revising — sometimes to the annoyance of my editor.

Then the book truly disappears.

But other things appear. Flap copy (the writing on the dust jacket) will show up for my response. I may rewrite that a bit. Even my bio on the dust jacket has been sent for my reaction and revision.

Also, I am sent sketches for the cover design and illustrations and asked for a reaction. I give it. They will almost always be revised. Usually that will be once or twice, but sometimes many times, as was the case of Gold Rush Girl.

Then, as happened yesterday, the first copy-edited version of the book comes through. I now see the book in print for the first time. (It was printed in, of all places, Italy!) A font was chosen. Its pagination has been set. The page layout was designed.

Many different people are involved in all of this. Not me.

Then the copyeditor weighs in. The copyeditor’s job can be basic — correcting spelling and grammar — but also bringing some (here and there) clarity or corrections to the text.

For Who Was That Masked Man Anyway? a question loomed. In the old radio show, did the Lone Ranger say “Hi yo Silver,” or “Hi ho Silver?”

In one book, the copy editor traced the escape movements of my protagonist and realized he was sailing in circles. A starboard tack was necessary somewhere!

In the current book, the copyeditor caught a lapse of a few hours in the narrative. It was important to the plot. I’ve reset the clock.

Reading the text in print is a different experience from reading a manuscript. I see that further changes are called for. I make them.

The book disappears again.

Revised book cover art pops up.

The book appears in its final form. Final? Once, when reading this “final” text I discovered three whole pages had been dropped.

At last — all of the above taking about a year — I am sent the actual book. All done. Except as I looked through The Man Who Was Poe. To my dismay, a crucial paragraph of cryptic code (part of the story) had been dropped, the printer thought it was gobbledygook.

Stop presses. The book recalled. The whole print run recalled! One page of that first printing was removed. A new page was printed and pasted in. By hand, I’m sure.

Now, we’re ready to put the book in your hands.

I hope you enjoy it.

I’m working on another book.

Repeat above.

April 1, 2025

When Short is Long

Wikipedia defines a novella as “a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories.”

There are debates as to what exactly this means, but there seems to be a general agreement that it is a story of no more than one hundred and fifty printed pages, and as brief as sixty. You can choose your own pagination.

My own definition is that a novella is a novel that you can read — in its entirety — in three or four hours. Obviously, that depends on your own reading speed, but I like the notion that you can read the work in one long sitting. In fact, one of the pleasures of reading a novella is that you absorb the whole narrative experience in one go.

Among famous novellas, there is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, published a hundred years ago. Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. James’ Turn of the Screw, Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and on it goes. You get the idea.

[If you go to the internet and type in “Best novellas,” you can find any number of long lists. I bet you may be surprised by how many titles you know.]

What’s not generally noted is that countless children’s book novels, in fact, fit the definition of novellas. You can start with Alice in Wonderland.

From this writer’s point of view, creating one is very satisfying. It’s no surprise then that I’ve written a good number. Among them, The Fighting Ground, The Button War, Something Upstairs. And the forthcoming The Road from Nowhere (January 2026, no cover image available yet).

I don’t mean to take anything away from the experience of a long novel, which has the reader living with characters and story for an extended, deep period of time and thought. I have a lovely memory of reading a Trollop novel, starting one early Friday evening, and spending all of a rainy Saturday — far into the night — luxuriating in all nine hundred or so pages. It was like living an extra life.

But there is a narrative tension and movement in a novella that can give enormous energy in the telling. Knowing that the reader will take them in with one (or two) immersive gulps means that you need to hone your prose to its sharpest edge, allowing for both poetic diction as well as insightful sparks of revelation. The short journey means there is not a lot of asking, “Are we there yet?”

In the revision process — which I always love — you need to be hard with your edits, precise in your vocabulary, smart in your plotting, and revelatory in character delineation. It’s also not beside the point that in the revision process, you can take in the whole novella, so it works as just that — the whole work. No room for a lot of loose threads — to mix my metaphors.

I’ll even go so far as to suggest that children’s fiction often has an outsized impact because it has the novella’s impact. Watch a young person read one.

Short novellas can bring long memories.

March 25, 2025

Fossil Phrases

If you were writing a story set in 19th Century America I’m sure you would not have a character say, “I’ll check my inbox.” But it would not be absurd to have a contemporary character say, “When I do that, I intend to pull out all the stops.” And yet “pulling out the stops” actually refers to pulling out all the stops on an organ to produce its fullest sound.

Our language is full of what I call “fossil phrases,” terms we still use that are based on things or acts from the past.

Consider, “She’s a flash in the pan.” The “pan” is a kind of tool for looking for gold in a stream, and that “flash” may well be a bit of valuable gold. But probably not.

Or we say, “That person is still in the limelight,” when a limelight was a non-electric type of stage lighting once used in 19th- century theatres.

And thinking of light, some of us still “burn the midnight oil,” which means working late, but surely not using an oil lamp to keep us going.

If you refer to a person as “a loose cannon,” as in creating havoc, you are not thinking of a multi-ton cannon, which having slipped its holding ropes, is rolling around the pitching deck of a mid-ocean warship wrecking everything. But it’s a good metaphor for certain wild-acting presidents.

When you sit down and take on a hard task, you might say “I’m going to bite the bullet,” but I bet you are not thinking of going through a medical procedure so distressing you are given a lead musket ball to bite into so as to alleviate the awful pain. I once saw a basket of such chewed bullets in a Civil War museum, and just to see them made me wince.

If you are going to start something at “the drop of the hat,” my guess is that you are not involved in a foot race that began (as used to be the custom) when someone dropped his hat as a signal to begin the race.

“One for the road,” references a charming British tradition. When taking someone to the gallows to be hung, there was a brief pause at a tavern for a drink of something alcoholic so as to give the victim the courage to face death.

And of course, if you are going “full steam ahead,” it’s not likely you have brought your boiler to the point of producing steam so as to get your locomotive up to speed.

“Up to scratch,” seems to mean the scratch line in the dirt, where you are supposed to be standing when about to engage in a boxing match.

Or that “gumshoe,” you hired probably does not mean the detective is wearing shoes with early 20th century gum-rubber soles so as to render him stealthy. But if you refer to him as a “private eye,” that’s a reference to the 19th-century Pinkerton Detective Agency’s logo. They were hired to protect Abraham Lincoln on the way to his first inauguration.

When I was a boy and a game was about to start, I’d shout “I’ve got dibs” to proclaim my right to go first. I had no idea the term came from an 1800s game played with sheep knuckle bones called, well, “dibs.”

If you read “the riot act” to your child, I bet you are not thinking of the act of the 18th century British Parliament which authorized local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and order them to disperse or face punishment. Then again, if you are confronted by twelve unruly kids it might be a good idea.

In short, the language we use is very much like a linguistic museum.

Readers are encouraged to submit their own examples of Fossil Phrases.

March 18, 2025

Options

Over the years, a number of my books have been optioned for movies. What does “optioned” mean? It means that someone, or some group, or some production company, has purchased the rights to start making a movie of the book. It doesn’t mean a movie will be made. It means a start to making a movie. A start might mean writing a film script. Or hiring a director. Or a host of other things. Or maybe the most important of all is raising money (millions) to make the film.

The actual making of the movie is a whole different and complex thing.

People pay money for such an option which is meant to last for X number of years. The purchase price for an option of my books has ranged from $1,000 to $21,000.

Over the years the books that have been optioned are:

Emily Upham’s Revenge

Night Journeys

The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle (It has been optioned multiple times.)

Nothing but the Truth

Crispin: The Cross of Lead

Something Upstairs

Let it be said none of my books has ever been made into a movie. True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle came closest when two weeks prior to the start of shooting, one of the star actors (and investor) was hurt in an accident, and the whole project collapsed. At the moment, it and Crispin are still under option, which means films just might be made.

Don’t hold your breath.

Filmmaking is both very complicated and very expensive. An option contract can be thirty pages long (single-spaced) and has a variety of clauses and conditions that have boggled my mind. It often contains the phrase “rights to all the known universe.”

One time when my agent was negotiating such a contract — which had that phrase — it was announced in the press that a new moon had been discovered circling the planet Pluto. Having a new grandchild, I asked my agent if she could reserve the rights (for that grandchild) to make a film of the book on that new moon. (Joke.)

Sternly, the agent replied, “Don’t even suggest it. They will think you know something they don’t. It will break the deal.”

One producer explained to me that making a movie was like building a very tall house of cards, the cards being script, director, actors, set design, cinematographer, editor, and on and on and on. (Next time you go to a movie look at all the people who are given credit for working on a film.) Remove just one of those cards — I was informed — and it will all come tumbling down.

One would-be producer wrote to me and said that he and his wife wrote horror films, which their children were not permitted to watch. “Our children asked us to make a film they could watch. Would I be interested in selling the rights to Poppy.” Sure, I said. I never heard from those folks again.

More recently a successful middle-aged film director asked me if she could acquire film rights to one of my books. “I first learned about it when you visited my elementary school forty years ago. I’ve always wanted to make a film of that book.”

Never underestimate the power of school visits!

Let it be said that in all of these options, I have never been consulted about how the film might be made. Once I did request a copy of the written screenplay. When I read it, I realized it left out what I thought was the defining moment of the book.

So I am well aware of how rare it is for a film adaptation to hew closely to the book, and more often than not will disappoint.

Then why give permission?

Simple. A film based on the book means that more people will read my book.

That I’d like to see.

March 11, 2025

Story behind the Story #74: Lost in the Empire City

In all the current political debates about immigration, it is sometimes forgotten, that unless you are connected to Native People, we are ALL immigrants or descended from immigrants, people in search of a better life. Some fled religious or political persecution. Others were seeking to get away from famine, violence, or deep poverty. Some just want to do better. They still are coming.

To be sure, a good deal of that immigration was forced, either by way of slavery or judicial expulsion from England to the British colonies as a form of punishment. Then, too, there were legions of indentured people, folks who crossed the oceans by giving up their liberty and labor for a period of time in return for passage and the promise of future freedom. There was even a group of men who, part of the British or Hessian army corps (during the War for Independence) escaped from their military overlords to become Americans. Also, folks who become part of America through conquest, as happened following the 1846 Mexican War and the 1898 Spanish-American War.

As someone engaged with US history, it was only natural that I have written about some of this. Thus these books all touch upon some aspect of immigration.

The Unexpected Life of Oliver Cromwell Pitts The End of the World and Beyond Night Journeys City of Light, City of Dark Beyond the Western Sea Gold Rush Girl The Man Who Was Poe City of Orphans Lost in the Empire City

Of course, Lost in The Empire City is set in New York City, where I grew up. The particular neighborhood where I lived was full of 19th buildings. The coal chute that is important in the story is something my parent’s 1835 house had — though in my day, it was long after any coal was delivered.

I can trace my own family history to France, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. My grandmother, Mariam Zunser, wrote a memoir (titled Yesterday) about her family, and her coming to America. In it she recounts the first time (as a child) she was given a banana to eat and had no idea how to eat it. The incident is replicated in Lost in The Empire City.

When beginning to write the book, while chatting with my friend and colleague, the illustrator Brian Floca, we discovered that our grandfathers — who immigrated from very different places in Europe — may well have lived in the same NYC neighborhood in the early 20th Century. One of the results of our talk led me to name the ship in which Santo and his family come to America (in the story) The Fulda. That was the ship upon which the Floca family came across the Atlantic.

There are a vast number of books that tell the story of immigration, both personal accounts, and historical studies. Some of those I read were about particular waves of immigration (e.g., Italian Immigration) or about the Ellis Island experience, as well as what it was like for the children of immigrants. As for old New York, go to YouTube NYC 1910, for some very early film.

Kids have a special place in immigrant history, for they embody the evolution of old worlds to the new. In many cases, because they assimilated faster than their elders, they became the guardians and protectors of their parents. Indeed, the premise of my book is young Santo’s promise to take care of his family, no matter what happens. And a lot happens.

Then there is the long legal history of immigration, people welcomed, people pushed away or not allowed in at all. All part of the tapestry of American history, the good, the bad, the endless but never effortless flow of people.

It was my intent that Lost in The Empire City become part of that flow. The novel is in no way about me, and yet, because of my family history it is all about me.

And millions of other Americans. Like you.

March 4, 2025

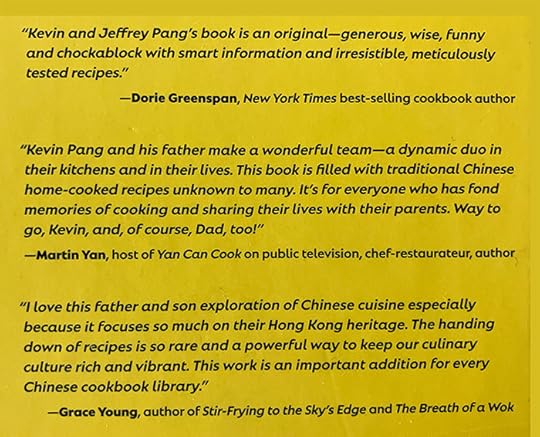

Blurbs

BLURB: “A short laudatory phrase — or even a word — that praises a piece of creative work.”

In the book world, blurbs are often placed on the back of the book jacket, or in the advertising for the book. The word is said to have been coined by the US artist and critic Gelett Burgess (1866–1951) in 1914. The British call them “puffs,” as in empty air.

If you look at books you have seen many a blurb, often laudatory words (“Amazing!” “Wonderful!”) or phrases (“The best book I’ve read in years!” “A thrilling thriller!”) on book jackets. They are there to entice a potential reader to buy or read the work.

Now the publisher Simon and Schuster has recently announced they will no longer put these blurbs on their books. My guess is that other publishers will follow suit.

If you are part of the book world you know that these laudatory remarks have been requested by the writer, the publisher, the book’s editor, or the publisher’s marketing department. It is often assumed (not necessarily correctly) by me — and others — that they have been written by the writer’s good friends.

I know that when I see all these remarks on the back of a book the only ones that hold meaning for me are the quotes from established, published, review publications. Such as — “An important history of a neglected time — New York Times.” I don’t even trust blurbs credited to well-known literary figures. To be sure they may even be honest responses. But embedded as they are in all those glittering phrases, I don’t believe them. They are rather like costume jewelry; pretty but not real.

I have never asked anyone to write a blurb for one of my books. That said, I have often been asked to write one. While I have almost always declined, I confess that over the years I have written three, perhaps four blurbs, when they have come from writers who are friends. In those circumstances, it was difficult — awkward — to say no. Fortunately in those few cases when I wrote them I truly liked the work, so at least I did not have to lie about my reaction.

The problem with “blurbs” is that there is always a need to publicly evaluate books. When you get solicited remarks it devalues legitimate responses. Because it is a fact in the life of a writer that if you publicly publish you are going to be publicly judged. When negative, such judgments can be painful, when stupid, it can be maddening, but when positive, it can also be a joyful, supportive moment.

Blurbs, however, are not to be trusted. Feel free to quote me.

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers