Daniel M. Russell's Blog, page 20

July 6, 2022

Answer: Why is there an elephant statue in this Wisconsin park?

An elephant in Delavan?

Seeing THIS in a mid-sized Wisconsin town was a huge surprise, and prompted me to look for the reason.

(As I've said before, the most common motivator for SRS Challenges is something that doesn't quite fit in... something I didn't expect. And I surely didn't expect a life-sized elephant and brightly painted clown in a small town parklet.)

In any case, this scene made me look twice and take the pic, and it leads to the following SearchResearch Challenge:

1. What's the story here? Why is there an elephant in the middle of small-town Wisconsin? Really? I did a little digging and my mind is boggled. Can any of this be true?

I started with the obvious search:

[ elephant statue delavan wisconsin ]

which gave me decent results. But I ALSO tried a longer, more question-based query:

[ why is there an elephant statue in delavan wisconsin ]

and THAT gave me rather different results. Here's a side-by-side comparison of the two SERPs.

In these two versions of the query, Google is trying to give you the best answers with-respect-to your underlying intent. In the short query, Google is guessing that you're looking for information about the statues in Delavan--how to get there, nearby attractions, etc. In the longer query (the more question-based one), Google thinks you're trying to find an answer to that question, "why is there an elephant in Delavan, Wisconsin?" and so it provides a more answer-base set of results, including an expanded snippet of information extracted from the first result (which is the same on both SERPs).

But as you can see, the second result ("Romeo & Juliet") is pushed farther down the page, and generally, the results are rather different.

What this means for you: These days, Google is getting increasingly good at answering full questions, or at least trying to give you links to results that will let you answer those questions.

Note: This doesn't let you off the hook... you still need to read and evaluate the results.

This Challenge is a great example of why this is so.

I opened up the top ten results in parallel in a single browser and looked at them in detail. Fascinating.

In #1, Statue of Romeo, we read that Romeo was just a bad elephant that killed 5 people in 15 years. He was infamous, and so the town (which had a rich circus history) decided to put up a statue commemorating Romeo and a circus clown.

But in #2, Romeo and Juliet, we read that Juliet died one winter on the shores of Lake Delavan and was then pulled out onto the ice of the lake by Romeo, possibly explaining why he turned mean. This page goes on to say that "fishermen still pull elephant bones out of Lake Delavan..."

#3 is a link to Wikimapia, pointing out the location of the statue.

#4 is a story about Romeo and Juliet, claiming that "following the 1853 season, Romeo and a smaller female, Juliet, were sold to the Mabie Brothers and delivered to the showâs winter quarters at the present site of Lake Lawn Lodge..." on Lake Delavan. (Which, coincidentally, was where I was staying while in Delavan.) This story adds a tidbit--that Juliet died of a bowel obstruction, but repeats the claim that she was pulled onto the ice for deposition in the lake. This article goes on to say that several elephant bones have been pulled from the lake since Juliet's death in February of 1864, during the height of the US Civil War. There's a specific claim that "in 1931, a newspaper article documented the finding of a bone in Delavan Lake, which some thought to be from a prehistoric mastodon."

The rest of the results are either recaps of these, or not especially useful.

But what we've got here should be enough to figure out what the backstory is about Romeo and Juliet.

This is obviously a job for a news archive, and my favorite of the moment is Newspapers.com (it's fast, accurate, broad, and available in many public libraries).

A search on Newspapers.com for:

[ Juliet elephant Delavan ]

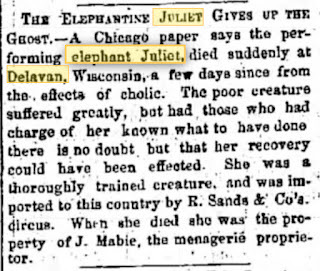

and quickly located several articles from 1864 such as this one from the Semi-Weekly of Milwaukee, WI. On March 16, 1864, they published this short blurb about Juliet:

P/C Semi-Weekly of Milwaukee, WI (3/16/1864)

P/C Semi-Weekly of Milwaukee, WI (3/16/1864)There's no mention of her burial in the lake, nor of Romeo being forced into pulling her there. All of the reports say the same thing: she died in February of 1864 at the site of the Lake Lawn resort (which was the Mabie circus company's overwintering site). The ground would have been frozen in February, and I bet that a lake burial would have been the simplest solution.

Although I tried, I couldn't find anything from those days about Juliet being dropped into the lake, nor about Romeo being forced to push her body into the waters.

Nor was I able to find anything about the mysterious "mastodon bones" from 1931.

So I turned to Google Books, and found several books (including the generally reliable Arcadia Publications ) about Lake Lawn which repeats the same story (Juliet died in winter, was pushed into the lake), Romeo goes on to kill 5 men, bones later found in 1931 thought to be mastodon... etc. But, unfortunately, none of these seem to point to contemporary accounts. It seems that the story of Juliet's burial-at-lake grew up sometime after her death. It's certainly possible that it happened, but there's no confirmation by news reports at the time. (At least not that i could find!)

On the other hand, I did find a poster of the Mabie circus (there are multiple copies of this poster floating around).

The playbill describes "the gymnastic elephants, Romeo and Juliet..." as part of the menagerie. And, as you see, there are illustrations of them at the bottom of the page.

The playbill describes "the gymnastic elephants, Romeo and Juliet..." as part of the menagerie. And, as you see, there are illustrations of them at the bottom of the page. The Clown: To be honest, I didn't think much about the clown (after all, seen one clown statue, and you've seen them all). But the comments thread was fascinating. I'm quoting Mike's comment here (with a little editing):

"I used to collect "First-Day Covers" ... specially decorated envelopes that contained a new stamp and was postmarked at the post office where it was issued.

The 5-cent clown commemorative was issued BY the U.S. Post Office, of course ... but it was issued AT the Delavan Post Office.

A simple search [clown commemorative Delavan] brings up lots of info, including the philatelic industry's standard Scott Catalog ID number for this stamp (#1309) and a wide variety of versions (including First-Day Covers) for sale on eBay and other sites. Most interesting to me was the 26-page program for the first-day festivities, whose description included "It also describes Delavan's circus history, including circuses that originated or quartered in Delavan."

Also found was this article in the Linn's Stamp newspaper that said the famous clown Lou Jacobs was the inspiration for the clown used on the stamp.

[Dan: I checked: Lou Jacobs was very clearly the model clown used for the stamp and the statue. Fascinating.]

That led me to search for info on Lou, finding biographies on Wikipedia, and also a new "-pedia" to me: Circopedia - The Free Encyclopedia of the International Circus.

Jacobs was in the first class (1989) inducted into the International Clown Hall of Fame, which was founded in Delavan in 1987, but moved to Milwaukee in 1997, and is now located in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

[Dan: Interestingly, I found that one of Lou's daughter's, Lou Ann, became an elephant trainer.]

Bottom line: Romeo was a big and bad circus elephant that was famous in the 19th century. He led a an unhappy life, and is commemorated as perhaps the biggest (literally) star from the circus town of Delavan, Wisconsin. Hence the statues of Romeo, a clown (Lou Jacobs), and (nearby) a giraffe.

SearchResearch Lessons

1. No surprise, but not everything you read is true... even in books. To be precise, by doing everything I could to find some validation for the story of Romeo and Juliet, I was able to find that Romeo was in fact a killer, and a generally bad elephant (but also that he was terribly abused during his lifetime). I was not able to verify the story of Juliet being dropped into Lake Delavan, although it seems plausible.

2. Once again, archival newspapers are a fantastic resource. Check out your local library to see if you have access to Newspapers.com -- or, barring that, use one of the other archival news sites we've discussed (e.g., Chronicling America)

3. Sometimes just asking the question is better than trying to guess the shortest possible query! This is a big change from a few years ago. When in doubt, try this first!

Search on!

Thanks again to Meredith Lowe, who first mentioned elephants and their bones in Wisconsin to me over coffee in Delavan. Thanks!

June 29, 2022

Where's Dan? A slight SRS delay this week...

I knew I'd be traveling this week,

.. but I also foolishly thought I'd have more time that reality allows. You know how it is: your trip seems like it will be all perfect timing and a relaxing time, but then reality pours in new tasks to do, people to see, and questions to answer. And that's what's happened to me.

This is actually a work trip, and by looking at the above pic, with the blue and white flag atop the church, you'll know exactly where I'm at. Can you deduce my location from the flag alone? (If not, it's open internet--I'm sure you can figure out what church this is...)

I'll be back next week with my solution to the previous SRS Challenge (the one about elephants in Wisconsin).

Search on!

June 22, 2022

SearchResearch Challenge (6/22/22): Why is there an elephant statue in this Wisconsin park?

I was driving through Delavan...

... a smallish town in southwest Wisconsin, midway between Chicago and Madison. I drove past something so unexpected that I went around the block and parked just to be able to take this picture.

To set the context, I'd been driving through lots of farmland, and then on several lakeshores. On the road are the usual things (corn fields, tractors, bales of hay, pontoon boats on lakes, people fishing on bridges), but then I spotted this life-size statue of an elephant rearing up, threatening a clown.

This made me look twice and take the pic, and it leads to the following SearchResearch Challenge:

1. What's the story here? Why is there an elephant in the middle of small-town Wisconsin? Really? I did a little digging and my mind is boggled. Can any of this be true?

Go ahead, dig into the backstory here and let us know what you find.

MOST IMPORTANTLY: How did you validate the story you found? Is is possible to get to a clear / credible / valid version of this story?

Search on!

Idea credit to Meredith Lowe, who first mentioned elephants in Wisconsin to me over coffee in Delavan. Thanks!

June 15, 2022

Answer: Why do gnats DO that?

... of gnats... I learned a few fascinating things by asking a few simple questions.

As I mentioned, one of the defining features of being great at doing SearchResearch is having a deep curiosity. In my work, I'm paid to be professionally curious, so I've developed a kind of permanently curious outlook on life. As I'm reading, or as I'm walking around in the world, I constantly ask myself questions: Is what I'm seeing actually what's going on? What caused that to happen? Why is this phenomenon taking place?

And so it was when I was walking on the beach. I saw the cloud of gnats circling around in a fairly tight swarm and wondered Why do they do that?

One great strategy for thinking about Why questions is to think of similar situations. In this case, What else flies in tight swarms, circling around a fixed point, rather than wandering off to another location?

That thought is what made me think of starlings and their murmuration flights.

So my Challenge was:

1. Why do gnats and starlings murmurate? (Is that even the right language to use?) What's a good search strategy to find the answer? Do they murmurate for the same reason?

I have to admit that I've only ever read of starlings in a murmuration, but I specifically chose that word to break you, my dear SRS readers, out of a habit. The obvious word would have been a "cloud of gnats" or a "swarm of gnats." But one of the traits of doing good research is to have a wide-ranging vocabulary--it's important to be able to ask a question in a different way, if only to get a different view onto a common topic.

"Murmuration" usually refers to starlings, but other birds (and animals) fly (and swim) in large groups in tightly coordinated turns, with different groups sometimes moving in synchrony, but in multiple directions, often forming lobes of groups staying more-or-less in one location. This is not giant groups of animals migrating--those are flocks or herds or schools.

While the starling murmurations are impressive, I wanted to see if it was ONLY starlings that murmurated, so I did a search for:

[ "murmuration of *" -starling ]

to look for other kinds of murmurations, finding that red-wing blackbirds, pelicans, sanderlings, robins, flamingos, and many other kinds of birds murmurate as well. (Pro Search Tip: Note that I'm using the star operator as a kind of fill-in-the-blank search, along with the minus sign to avoid results with the word starling in them.)

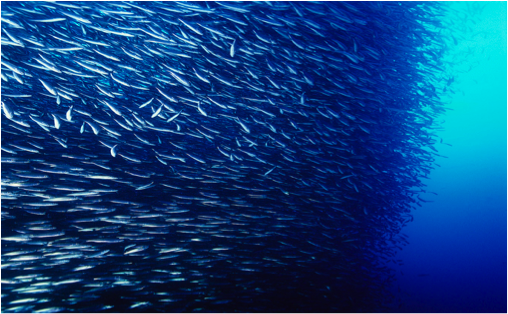

And of course, fish often do something very similar when they form "bait balls" to escape predators. (See this great video from Blue Planet--watch at 1:05 to see a remarkable bait ball murmuration.)

A bait ball of sardines. Large bait balls also murmurate. P/C OpenStax College

A bait ball of sardines. Large bait balls also murmurate. P/C OpenStax College

What about gnats?

(BTW, what IS a gnat anyway? It's important to know your terms when you start a search! A quick definition search told me that gnat is a collective word for many species of small flies that do not bite. In some areas, gnats are also called midges. Gnats only live long enough to mate and lay eggs.)

If you fell into my suggestion and did a search for:

[ gnats murmuration ]

you probably saw some wonderful videos of gnats flying in clusters, BUT by looking down the SERP, you'll quickly learn that "swarm" is the preferred term for gnats (just as "murmuration" is the preferred term for starlings and birds, while "bait ball" is preferred for fish).

So I'm going to modify my query to be:

[ why do gnats swarm ]

and find a bunch of results, the first four which look to be from credible sources (a nature conservancy website, two science journal sites, and the U. Kentucky department of entomology), each of these with articles about "why do gnats swarm?"

All of the sites agree: it's all about mating.

The science news site tells us that

"The swarms make it easier for the male and female gnats to find each other and mate..." and that "Gnats will often congregate around objects or other visual markers that contrast the landscape, such as fence posts...This helps the females more easily see in the swarm. [Turns out that] ...0nly male gnats swarm. The females then identify the swarm and enter it to mate."

Since gnats don't live very long, it's important to have a fast and easy way to find a mate. Swarming is one very visible and simple way to do that. Think of it as speed dating for tiny insects.

But gnats are long-lived compared to mayflies: they live in the mud of a riverbed for up to three years before hatching. After reaching hatching and growing to adulthood before emerging on the waterâs surface, adult mayflies only have about three hours to mate. As you can imagine, this makes for a pretty frantic mayfly swarm. In these swarms, frenzied insects create a dramatic (and to some, dramatically revolting) congregation. One was so large that it appeared as a rainstorm on weather radar. (For a video of a mayfly swarm, see this NatGeo video.)

Interestingly, starlings seem to murmurate as a kind of group defense mechanism; it's difficult for a predator to track an individual when they're swirling around in a giant mob.

By contrast, when gnats swarm, it's easier for some predators to fly through the cloud and pick up multiple meals at once. (That's the way dragonflies will sometimes feed in swarms of gnats. This is so common that it's got a specific term: swarm feeding.)

So what works as defense for the birds, doesn't work out so well for the little insects. Well, if you're a mayfly, you're time limited, so procreation beats out your survival instincts!

1. Curiosity matters. It's not hard to develop the practice of being curious--it's just a matter of asking questions and then doing your SRS to find the answers. It's a great way to learn about the world (and develop that little twinkle in your eye that leads you to ask, "I wonder if...")

2. Be sure to check definitions. I hope murmuration is now in your vocabulary, and that you know it usually refers to starlings (but not exclusively).

3. Check for near-misses: What else is like this thing? Up above I used the * operator along with the minus operator ( - ) to search for alternatives ("other things that murmurate, but don't tell me about starlings"). Once you know what else is nearby, you'll understand the large concept space--the specific answer to your question along with other things that tell you what's nearby or closely associated with it.

As always... Search On!

(And in Dan's addendum: Stay Curious!!)

June 8, 2022

SearchResearch Challenge (6/8/22): Why do gnats DO that?

At the beach I ran into a cloud of gnats...

... and maybe you have as well. Annoying, amirite?

One of the defining features of SRS is a deep curiosity about things that you find, or in this case, you stumble into while on walkabout. I grabbed this short video because I could actually see the gnats against the darker rock in the shadow. They seemed to form an almost stationary cloud over this brighter patch of rock.

I stood there for several minutes watching the cloud swirl around almost like a tiny murmuration of starlings. I'm sure other people walking on the beach thought I was daft, staring at something they couldn't see, moving my hand slowly to see if they'd move out of the way. (Answer: they'd dodge my hand, but the mass of gnats stayed hovering over the same place.)

When I find something like this, I get curious and starting asking myself some basic questions: Why? How? What-for?

And then I usually head home and search for deeper answers to the questions that rise to the surface. (And if it's a really interesting thing I see, I write down the questions for later research. As someone once said, "the most profound misunderstanding of human memory is that you'll remember that later...")

So my Challenge for you, after my beach walk is this:

1. Why do gnats and starlings murmurate? (Is that even the right language to use?) What's a good search strategy to find the answer? Do they murmurate for the same reason?

It's a great, curious thing to see beautiful behaviors in the world and try to understand them. Tell us what you did to understand these behaviors. Let us know in the comments below, won't you?

Search on!

June 1, 2022

Answer: Finding original patents?

Patents don't define a market...

... but they're a decent proxy for when a market comes into being. This week's Challenge asks about finding the patent dates for two devices that are fairly clever, definitely deserving of patent protection.

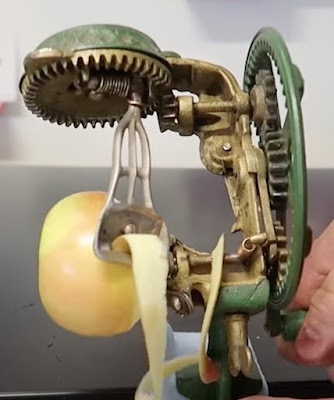

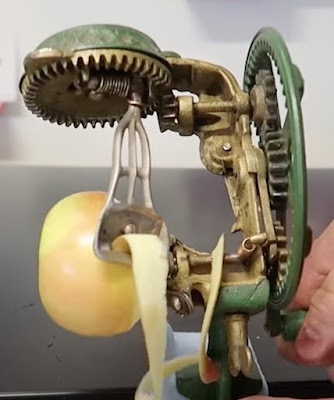

Can you find the patent dates for these two devices?

1. What's the patent date for the apple parer seen above? (See another view below for a similar device with an apple in place.)

I remember that Google has a Patents corpus (Patents.Google.com), so I went there and searched for

[ "apple parer" sargent foster ]

-- surprise! There were NO results!

When I did the search without Sargent, I found this patent for an "improved apple parer" (US116943, July 11, 1871), by Calvin Foster. It's much more complicated than the device shown above, but it also slices the apples as they're pared.

But I was expecting to find a patent with both Sargent and Foster's names. And this isn't it--is there another patent?

To explore a bit, I did a slightly different search without using the exact ("parer") term found in the advertisement--this was my second try at searching for the title (or claims) of the patent. I used:

[ apple paring Sargent Foster ]

but as you might expect, there were a lot of results. Luckily, the result I was searching for was in the 5th position:

You have to read through the OCR failures ("Machine fob pabiwg" should be "Machine for paring apples"). Luckily, the full-text is recognized correctly, which is why my search for "paring apples" worked.

I was curious if I could be more precise, so I put in a date restriction by using the Patents search UI. Here you can see I put in Jan 1 1871 as the latest date I was interested in. (I just guessed this--looking at the style of the drawing, it looked like 1871 or earlier.) Lo and behold, the search is very precise:

This search returns exactly the one result for patent US10078A (1853), the "Machine for Paring Apples."

With this as the original artwork:

Note that the text "Apple Parer" is handwritten in the diagram.

Note that the text "Apple Parer" is handwritten in the diagram. Apparently the OCR doesn't recognize that text in the illustration.

Interestingly, it was invented by Ephraim L. Pratt of Worcester, MA, and then assigned to J. Sargent and Dan P. Foster, as shown in the "Sargent and Foster's Patent" on the top image.

Assigning a patent transfers the ownership of the patent from the inventor (Ephraim) to the persons (or business) that will then own the patent.

And now you can see the mistake I made in the first search--I found "An improved apple parer" by Calvin Foster, that was not the original invention by Pratt in 1864 and assigned to Sargent and Dan Foster. I can speak from personal experience--"Dan" is not the same as "Calvin."

As I poked around, I found even more patents by Ephraim Pratt--turns out he invented multiple apple paring inventions! (Here's another one assigned to George Carter from 1864.

Bottom line: patent US10078A for the device shown above, was 1853, the "Machine for Paring Apples."

2. And the device that captured my heart, a stapler that works WITHOUT staples! When was this (or something very much like it) first patented?

I was curious if I could find this using "regular" Google search, so I tried this search:

[ stapleless stapler ]

and then looked at the images--was really surprised to see that there's an entire universe of shockingly colored stapleless staplers out there.

By looking at these results, it would seem that this is a "Bump Fastener" from the Bump Fastener Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin. (Notice that there's even chip in the upper left corner about "bump paper fastener.")

Searching for [ Bump Fastener Company ] quickly got me to the official LaCrosse County Bump Fastener page, which tells me that "...this handy office tool fastens two or more pieces of paper together. The fastener cuts a small triangular-shaped hole in the paper, folds back the cut triangle, and then slides it into a slot cut in the paper to fasten it in place." And that it was invented in 1910.

That's our gadget!

(And yes, search-by-image works quite well, as does a Lens search.)

But there's more to this history. From the same web page:

"Bump invented and patented other inventions while living in La Crosse, including an air compressor pump, a terminal clamp, a carburetor-adjusting mechanism, a rotary engine and many others. In 1930, Bump changed his company name to the Bump Pump Co., based on his new invention. However, the company was still producing his first patented invention, the paper fastener."

I have to admit that I was interested in the backstory, so I did the obvious search in newspapers of the day and found this lovely story:

LaCrosse Tribune, 3 Aug 1930, before the company name change,

LaCrosse Tribune, 3 Aug 1930, before the company name change,I'm not sure I would have called this a "Combination of Romance, Struggle," but things were different back then. To LaCrosse, this was hot, front-page news! SearchResearch Lessons

Before I get to the lessons I learned, I want to point out that several RegularReaders wrote exemplary SRS discussions and I want to point you to them.

Art Weiss wrote about his great voyage of discovery (which I thought about using for today's text). He also taught me about Espacenet, which is a great patent search engine--well worth knowing about. I especially like their advanced patent search UI which is especially easy to use.

Remmij, as usual, found some intriguing pages, including a site I didn't know about, the Early Office Museum Website, which pointed out that "..[stapleless fasteners] were introduced in 1909 by the Clipless Paper Fastener Co. and in 1910 by Bumpâs Perfected Paper Fastener Co. A Clipless Paper Fastener and the Bump Paper Fastener cut and fold small flaps in the papers in a way that locks the papers together. Bump machines were still marketed in 1950. Curiously, the model of the Bump Stand Machine that was introduced in 1916 was sold until 1950 with the words "Patent Pending." "

Mateojose1 did a marvelous job of walking us through their search process with a nice description of side-journeys.

Ramón points us to this amazing video of an 1870's peeler being restored and used. Which reminded me to search on YouTube for a Sargent and Foster apple peeler video in use.

My observations:

1. Read carefully. I know I say this all the time, but when I was initially searching, I misunderstand Calvin Foster's name, thinking that only one person named Foster would be involved in apple peeler patents. How wrong was I!

2. OCR is inexact.. especially in older documents (like 19th century patents). Sometimes you have to "read through" the OCR errors to get to the good stuff.

3. Don't be afraid to try alternative versions of your query. Note that when I tried searching on patents for "Apple Parer," it didn't work too well. But "Apple peeler" did!

4. Because this is the internet...there's a specialty group for everything. On a lark, I did a search for just [apple parer] and found the Apple Parer Museum, which has a page just on the Sargent & Foster paring device. Go figure.

Search on!

May 25, 2022

SearchResearch Challenge (5/25/22): Finding original patents?

I found the most remarkable machine...

... just a few years ago. I'd gone to a farm auction in upstate New York where a longtime family in the area was getting rid of the old homestead and everything in it. If you've never been to such an auction, it's worthwhile, if only to see gadgets and gizmos that you wouldn't believe.

At this auction, I found two gadgets that amazed me. I grew up in LA, where we didn't have such things. I could figure out what they did, but I was surprised to see how old they were. And that, naturally, led me to try and dig up when these devices first came onto the market. Or, for today's Challenge, when were they first patented. (The patent date being a good proxy for the date they entered the marketplace.)

Can you find the patent dates for these two devices?

1. What's the patent date for the apple parer seen above? (See another view below for a similar device with an apple in place.)

2. And the device that captured my heart, a stapler that works WITHOUT staples! When was this (or something very much like it) first patented?

The one I bought (oddly enough, for $2.00) has long since been lost to me in one move or another, but I remember it fondly. It could "staple" about 5 pages of paper together by cleverly punching a tongue-shape in the paper, and then tucking the tongue through a little cut made behind the tongue. (This makes sense if you look at the image below.) The tongue is punched out, and then threaded through the slit on the right.

Can you figure out the patent dates for these two VERY clever devices?

Let us know what resources you used, and what queries you did to find them.

Search on!

May 20, 2022

Answer: Why... in New Orleans?

Yep... I was in New Orleans...

P/C Hitesh Choudhary

P/C Hitesh Choudhary... at a conference with just over 2,000 of my friends. It was a wonderful time, right up until the last day when I felt pretty sick (felt like a bad head cold + muscular soreness). I figured it was the flu, but out of an abundance of caution, I got a COVID RT test from the pharmacy and found that I was positive!

I was a long way from home, so I stayed, isolated in a local hotel until it was okay for me to be out in polite company again. It wasn't New Orleans fault--it's still a wonderful city--but too many people, too soon, in quarters that were a bit too close.

But now we know.

Before that happened, I had a couple of SRS questions that popped up for me this past week. Can you help me figure them out?

1. One of the great symbols of New Orleans are the steamboats that used to ply the river. They're wedding cakes on the water, full of color, decoration, and outsized components. They don't use propellers, they use giant paddlewheels driven by large steam engines. One of the most noticeable parts of a traditional steamboat are the smokestacks. In this image of the riverboat "City of New Orleans," you can see that the top of the smokestack ends in an incredibly elaborate patterning at the very top. Since you see this kind of thing on nearly all steamboat smokestacks, that made me wonder--is that patterning at the top purely decorative, or does it have some kind of function? What can you find out?

I did a search for:

[ steamboat smokestack decoration on top ]

to start. Note that I did NOT include any localization information (not Mississippi, nor New Orleans), trusting that the results I'd get would be already localized to the US. (If you do this query in other countries, you might get very different results. In such cases, you'd probably have to include some locale identification information.)

In the results to this query, I found a great source, Riverlorian.com (by Jerry Hay, author of multiple books about US river lore and a guide aboard the American Queen and the Delta Queen Mississippi steamboats). In this site, Hay writes that:

"Steamboats had tall smokestacks. The boats originally had boilers fired by wood. Along with the smoke there would often be flaming embers coming up from the furnace and out of the top of the smokestack. Those embers could and did start fires when they landed on the top deck or cargo. Tall stacks would give the embers a better chance to burn out before reaching the deck. In addition, the top of the stacks were "fluted". Fluting consisted of wire or steel mesh and acted like a small fence that would break the embers into small pieces. Smaller embers were more likely to burn out faster than larger pieces. As fancier boats were built, the fluting became very ornamental and eventually came to be considered an essential decorative element of the smokestack. Those vessels with the fancy smokestacks and decorative flutes became known as high-falutin' boats."

It's pretty clear that the design of these steamships was very fanciful, full of enough decoration to choke a horse. In 1886, one of these steamships was described in The River Road Rambler as:

The J. M. White... was 325 feet long with a public salon large enough, it was said, to hold three-hundred waltzing couples under âseven 16-burner gold-gilt chandeliers⦠made of fine brass, highly polished, and then⦠covered with pure gold.â

There were also stained-glass windows, ample staterooms with full-size beds, and one of her two bridal chambers was paneled in mahogany and satinwood, the other in rosewood and satinwood...

You get the idea. Decoration for its own sake was happily accepted, but the decorative fluting atop the smokestacks also seemed to be primarily decorative. The spark arrestors (such as they were) seem to have been simple "wire meshes" (as Hays writes). Meanwhile, other contemporary steamships, like the Multnomah (1851), which served in Washington state, had fairly elaborate spark arrestors.

But here's the thing--spark arrestors, as seen on the Multnomah, were fairly well-developed technology. By the time of the great Mississippi steamboats like the Natchez or the City of New Orleans, spark arrestors were well known gadgets. In fast, the patent office had more than a dozen patents for improvements to spark arrestors filed before 1890. Most involved a distinctive swelling in the stack to contain the arresting mechanism!

US Patent for an "Improved Spark Arrestor" (1855)

US Patent for an "Improved Spark Arrestor" (1855)  Two steamboats in Memphis, 1906--one with spark arrestors (left) and

Two steamboats in Memphis, 1906--one with spark arrestors (left) and one with only screen arrestors (right).

P/C Library of Congress.

But spark arrestors are something else to maintain and are prone to getting deposits of creosote from the burning wood (and then catching on fire themselves).

So the elaborate leaf-like structures seem to have evolved from the meshes built in to arrest sparks and embers. But as far as I can tell, they don't actually do much to suppress anything. (They do look very cool, however...)

2. While New Orleans is a generally colorful place, three colors seem to dominate: purple, gold, and green. Is this color scheme really a thing? Or am I making a vast overgeneralization?

I'm going to quote much of mateojose1's explanation (which is very well done).

Mateojose1 writes (I've lightly edited it here):

Search query #1: [ new orleans purple gold green ]

Source: MardiGrasNewOrleans.com tells us that these are the colors for New Orleans' Mardi Gras celebration, with each being said (in 1892) to represent three different virtues (gold = power, green = faith, purple = justice). The story goes that they were selected in 1872 to honor a Russian grand duke who was visiting. But, it's a story that doesn't quite fit the facts.

This site also tells another version of the story: According to local historian Errol Flynn Laborde, is this: The carnival king did say (in 1872, for the first rex parade) that those would be the three colors for Mardi Gras, but he never said why. At that point, Laborde asked why. And, after investigating, he concluded that the three had to do with how its organizers decided that the Rex parade needed a flag with three colors: Purple, for royalty ("rex" means "king"); gold, since heraldry needed a metal and gold was fit for a king; and green, since heraldry also needed a color, and since green went the best with purple and gold.

(Dan's comment: Here are the details about Laborde--he's a long time journalist and editor focusing on local history and New Orleans culture.)

Source: NOLA.com Retells the 1892 story of the three colors symbolize, and tells us that the three Mardi Gras colors are seen year-round throughout New Orleans.

Search query #2: [ new orleans purple gold green origin ]

Source: MyNewOrleans.com Another article written by Errol Laborde in 2020, which explains his findings in more detail. They date back to a proclamation by the 1872 carnival king, but it's unclear why he chose those three rather than some other choice, plus none of the other explanations can be verified. That, and the popular explanation for what they mean was debunked in 1971.

25 years later, Laborde and others who were researching were able to deduce why those three were selected. They were as follows:

* The carnival king needed a flag, which needed three colors (since the America, British, and French flags are all tri-colored). Red, white, and blue were dismissed, since they were colors for republics and revolution, which would not be appropriate for a king.

* Purple was likely chosen because it's long been connected with royalty.

* They also followed the rules of heraldry (which the people who organized the Rex event were likely familiar with), and those fields need both a metal (gold or silver [white]) and a color (black, green, purple, blue, and red). So, gold was chosen (since white was widely used), and green was chosen, since black didn't go so well with gold and purple.

Conclusion: The three colors represent Mardi Gras, and are based on what was chosen for it back in 1872 (the selection of which was related to heraldry), though a separate explanation was invented in 1892. Now, though, it's a matter of civic pride for the city, and for its Mardi Gras celebration.

(Thanks, MateoJose1.)

3. There also seems to be an awful lot of fleur de lis in the decoration of New Orleans, you see them absolutely everywhere (including between the smokestacks above!): Why?

I started with the Wikipedia article by searching for [ fleur de lis wikipedia ]

I found that the symbol is associated with European monarchs, but especially with the French monarchy. Oddly, its use in France seems to predate Christianity, as Roman coins from Gaul had a design that looked like it. It also appears in other countries, but it's most closely associated with France.

My next query is the obvious one: [ fleur de lis new orleans ]

There are tons of results, but one that looked reliable is the paper of record for the city, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate which repeats the story of the fleur de lis as a French national symbol, but also tells us that in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, it came to represent strength, determination in rebuilding the city, and defiance against the storm.

Background: As Jon pointed out, in 1604 what is now eastern Canada was extensively populated by French people. Eventually the area became part of the British empire and around 1754 most of the 10,000 French were removed to other areas. By 1764 they were allowed to return under certain conditions: mostly so long as they would disperse themselves and swear loyalty to British Crown. These people became knows as the Acadians.

Those returning to the Canadian Maritime provinces chose to settle in Baie Sainte-Marie in western Nova Scotia, Cheticamp on the western shore of Cape Breton Island, the Malpèque region of Prince Edward Island, and on the eastern and northern shores of New Brunswick as well as in the province of Quebec, particularly in the area of Yamachiche and L'Acadie.

Many Acadians from France and the American colonies settled in Louisiana during the Le Grand Dérangement eventually transforming the word "Acadian" into "Cajun," in the process creating a new French dialect and culture to the world. Along the way, they also brought their symbol of France with them.

The fleur de lis represents the city's French heritage.

This was a fun Challenge, exercising our ability to read multiple sources and find the answers we seek. If there's a big lesson from this week it's this:

1. Read multiple sources for every answer you seek. In all of the above research, we sought out multiple sources for every claim made. We also checked the sources themselves (e.g. "who is Errol Labourde?") Some of these require close reading, an essential skill for the practical SearchResearcher!

Search on!

May 17, 2022

Superb example of SearchResearch... in Algeria

I have a wonderful video I want to recommend to you. It's about what this mysterious circle of circles is...

In this video from Vox, they explore the limits of what you can find by internet searching, and go beyond the limit when they realize that they'll have to visit this site in person. It's not exactly around the corner: it's at 27.270161, 4.322245, which is, you'll quickly realize, in the middle of the formidable Algerian desert.

The key question is: When / what / who made these circles in the (literal) middle of nowhere?

I didn't expect to watch this entire video, but it is well worth the time. In it, the researchers do all of the things you'd expect from a SearchResearch Challenge (finding original sources, locating experts, contacting them, etc). It's a wonderfully produced video that lays out their research process step-by-step. Check it out, and tell me if you're not pulled into the mystery after the first 30 seconds.

Bravo, Vox! Bravo!

Vox's video: Who made these circles in the desert?

Search on!

May 11, 2022

SearchResearch Challenge (5/11/22): Why... in New Orleans?

This past week I was in New Orleans...

P/C Hitesh Choudhary

P/C Hitesh Choudhary... that fabled city along a bend of the Mississippi, home to classic jazz, crawfish etouffee, po boy sandwiches, and a confluence of many cultures from around the world.

It's a colorful place with a long and complicated history, and for this traveler, a nearly endless source of great SRS questions. Here are two that popped up for me this past week. Can you help me figure them out?

1. One of the great symbols of New Orleans are the steamboats that used to ply the river. They're wedding cakes on the water, full of color, decoration, and outsized components. They don't use propellers, they use giant paddlewheels driven by large steam engines. One of the most noticeable parts of a traditional steamboat are the smokestacks. In this image of the Natchez, you can see that the top of the smokestack ends in an incredibly elaborate patterning at the very top. Since you see this kind of thing on nearly all steamboat smokestacks, that made me wonder--is that patterning at the top purely decorative, or does it have some kind of function? What can you find out?

2. While New Orleans is a generally colorful place, three colors seem to dominate: purple, gold, and green. Is this color scheme really a thing? Or am I making a vast overgeneralization?

3. There also seems to be an awful lot of fleur de lis in the decoration of New Orleans, you see them absolutely everywhere (including between the smokestacks above!): Why?

As always, be sure to tell us what you found out.. and HOW you found out! (Tell us your process and citations. We want to learn from you.)

Search on!