Daniel M. Russell's Blog, page 12

January 17, 2024

Answer: How do you use LLMs in your SearchResearch?

So....

P/C Dalle3. [an evocative picture of data, data tables, line charts, histograms]

P/C Dalle3. [an evocative picture of data, data tables, line charts, histograms]It looks like many of us are using LLMs (Bard, ChatGPT, etc.) to ask SRS-style questions, especially ones that are a little more difficult to shape into a simple Google-style query.

That's why I asked this week:

1. How have you found yourself using an LLM system (or more generally, any GenAI system) to help solve a real SearchResearch question that you've had?

I've also gotten LLM help in finding answers to SRS questions that I couldn't figure out how to frame as a "regular" Google search. Bard has answered a couple such questions for me (which I then fact-checked immediately!). While the answers might have a few inaccuracies in the answer, the answers are often great lead-ins to regular SRS.

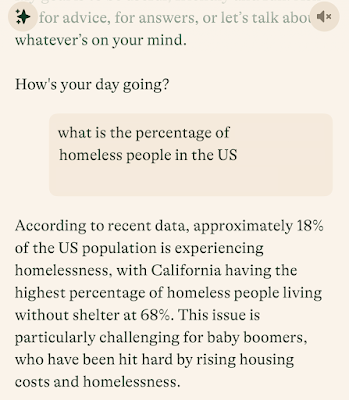

For instance, I asked Pi (their home page) a question that has been in the news recently: "What's the percentage of homeless people in the US?" Here's what it told me:

My first reaction was the obvious one--that can't possibly be correct! 18%???

The strangeness of the answer drove me to do a regular Google search for some data. At the Housing and Urban Development website I found this: "The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) counted around 582,000 Americans experiencing homelessness in 2022. That's about 18 per 10,000 people in the US, up about 2,000 people from 2020."

Or, if you do the math, that's around 0.18% of the US population.

When you look at multiple sites, you'll keep seeing that figure "18 per 10,000 people," which I could imagine an LLM rendering as "18%" in some twisted way. Arggh!!

Interestingly, when I did this on Bard and ChatGPT on the same day, they ALSO quoted 18% as the homeless rate.

However... if you ask all of the LLMs this same question today (1 week after they told me it was 18%), they all get it right: the real percentage is 0.18%.

That's great... but also worrying. I'm glad they're in alignment with more official sources, but the underlying data didn't change--some training must have kicked in.

You can't count on consistency with an LLM.

*

But... I find myself increasingly turning to LLMs to answer questions that really are difficult to frame as a search query. Previously I wrote about finding "Other words that are like cottagecore" as an example of the kind of task that an LLM can do well. They can take fairly abstract language ideas (e.g., "what words are like these words...<insert list>") and come up with something fairly useful. This is a great capability that will let us take SearchResearch questions in new directions.

You can ask follow-up questions without having to include everything you've found out thus far. THAT is a pretty big advantage, especially for more complex tasks that take more than 2 or 3 queries to answer.

*

This past week I found a really interesting paper on our topic by some folks at Microsoft Research. In their Arxiv paper, "Comparing Traditional and LLM-based Search for Consumer Choice: A Randomized Experiment" they compared ordinary search tasks where some people used a "traditional" search engine, while another set used an "LLM-based" search engine. (The LLM was ChatGPT and was primed with an extensive prompt before people started their searching.)

Intriguingly, they found a couple of interesting things:

* people spent less time doing LLM search than trad search,

* they did fewer, but more complex, searches that trad search,

* on the whole, the two conditions were just about as accurate (but see below),

* the searcher's perceptions of accuracy were pretty high, even when the answers weren't great.

They then did a nice intervention to see if they could color-code uncertain results in the LLMs output to see if it would help make everything more accurate. The result? Yes, significantly so. (Although they still had to have a magic oracle know that the results were low-quality!)

However, one of the Challenges they had their participants do was intentionally a hard question that they knew the LLM would give terrible answers. But it didn't matter much--people believe LLMs beyond what they should.

That's not a huge surprise, but a good cautionary note for us. You still need to check to make sure that the results you're getting actually jibe with reality.

So... what do I use LLM search for these days? I'm asking it a lot of knowledge summarization questions. Things like "Give me an overview of how epigenetics works in humans. Tell me assuming I have a college level degree of genetics knowledge."

With this prompt, ChatGPT does a pretty good job. Here's the opening paragraph of its response:

Epigenetics is a fascinating field of study that explores the mechanisms by which gene expression is regulated without altering the underlying DNA sequence. It plays a crucial role in development, cellular differentiation, and the adaptation of organisms to their environment. Here's an overview of how epigenetics works in humans, tailored to someone with a college-level understanding of genetics...

On the other hand, if you ask for an explanation at a 6th grade level of biology knowledge, you'll see:

Alright, let's imagine our body is like a huge library. This library (our body) has lots of books (cells), and each book has the same set of instructions or recipes (DNA) for making you, well, you! But even though all the books have the same recipes, not all recipes are used in every book. Some recipes are for making eye color, some for hair color, and others for how tall you'll be. Now, epigenetics is like having special bookmarks or notes in those books that decide which recipes are going to be used or ignored....

These kinds of summaries are incredibly useful, and much more sophisticated than the abstracts / snippets beneath each web result on the SERP. The ability to ask for more-or-less detail in the prompt is incredibly useful.

*

On the other hand... you still have to be careful about the simplest of things.

If you ask Bard [ how many cups are in a gallon? ] it will reply: "There are 16 cups in a gallon. This applies to both US liquid gallons and imperial gallons, although they have slightly different volumes."

Of course, that doesn't make sense. An imperial gallon is 1.2 US gallons, so they can't have the same number of cups! This is a classic measurement blunder: there are, in fact, 16 Imperial cups in an Imperial gallon. (For the record: There are 19.2 US cups in an Imperial gallon.) As always, check your facts... and check your units! (And for the record, ChatGPT explains this: "However, it's worth noting that the imperial cup and the US cup are not the same in terms of volume: 1 Imperial gallon = 16 Imperial cups, 1 Imperial cup = 10 Imperial fluid ounces.")

SearchResearch Lessons1. It's worth reiterating that you shouldn't assume that the output of an LLM is accurate. Think of it as incredibly handy and useful, but NOT authoritative. Tattoo that on your hand if you need to, but never forget it.

2. Always double check. As we saw, LLMs will make bone-headed mistakes that sound good... so since you're not assuming that the output of an LLM is accurate, make sure you double-or-triple source everything. Do it now, more than ever.

Keep searching!

January 10, 2024

SearchResearch Challenge (1/10/24): How do you use LLMs in your SearchResearch?

It's a New Year!

P/C Dalle3. [an evocative picture of data, data tables, line charts, histograms]

P/C Dalle3. [an evocative picture of data, data tables, line charts, histograms]Let's reflect on what SearchResearch is all about...

I started this blog back in January, 2010 with About this blog--Why SearchReSearch? That was 5,093 days ago.

So far, there have been 1,374 posts, with 4.75M views and 13,700 comments. We're running around 40K blog views / month, and that doesn't include the various syndicated versions of the blog. If you include those, I'm Fermi Estimating the readership at 50K /month. That's a decent number (roughly 1,660 people / day).

As longtime SRS readers know, one of my goals was to use the blog as an effective prompt to write a book. That book--The Joy of Search: A Google Insider's Guide to Going Beyond the Basics--came out in September 2019 and has done reasonably well. At least well enough to be translated into Korean and Chinese, as well as go into a paperback edition.

As my Regular Readers also know, I'm working on another book ("Unanticipated Consequences") which I'm trying to finish up in the first part of this year, 2024.

Writing a regular blog is a serious investment of time and energy, at least it is for me. On average, I spend around 4-8 hours each week bringing you the most interesting SearchResearch tidbits I can find.

But it's a big time commitment, and I'd like to use those hours to work on the new book.

So I'm going to try an experiment--scaling back a bit, trying to do each blog post in two hours or less.

To do that, I'm going to try to involve you Regular Readers a bit more in the search for insights.

As we've discussed, the advent of Generative AI is promising to radically change the SearchResearch process. It has the ability to give us new insights quickly (an example), and also to generate convincing-sounding nonsense with ease (an example).

I know that many of you are using ChatGPT or Bard or Llama to answer questions, so I want to tap into the collective intelligence that SRS Regular Readers can bring to the discussion.

I've asked this before in general (How can we use LLMs to search even better?) and for the specific case of medical searches (How might we best use LLMs for online medical research?). But if there's one thing to know about LLMs and Generative AI in general, it's that this field is changing fast--really fast--fast as a flash rifling down the electric blue gun barrel into a sea of new-age synth-pop psychedelia.

So...

Our SearchResearch Challenge of the week is this is to revisit this:

1. How have you found yourself using an LLM system (or more generally, any GenAI system) to help solve a real SearchResearch question that you've had?

I've told you before that I've used ChatGPT to help me with some data table manipulation. I've solved a few problems in a minute that would have taken me an hour or more to do with my regular programming skills. Those are huge savings.

I've also gotten LLM help in finding answers to SRS questions that I couldn't figure out how to frame as a "regular" Google search. Bard has answered a couple such questions for me (which I then fact-checked immediately!).

We all want to know what you've found to be useful. What has worked for you in the past few months?

Alternatively, what has NOT worked out for you?

We're all ears here at SRS!

Keep searching.

P/C Duet AI (Google Slides) [kangaroo on top of piles of text listening ]

P/C Duet AI (Google Slides) [kangaroo on top of piles of text listening ]

December 22, 2023

Answer: What makes a national dish?

If fondue isn't a national dish,

I'm fond of fondue.

I'm fond of fondue. ... what is it?

Well, it IS a national dish, but as I mentioned last week, fondue was popularized as a Swiss national food by the Swiss Cheese Union (Schweizerische Käseunion) beginning in the 1930s as a way of using up the local excess of cheese. The Swiss Cheese Union created pseudo-regional recipes as part of the "spiritual defence of Switzerland" before World War II to help out the cheese makers and the dairy industry. (For more details, see this wonderful article about the cheese cartel that made fondue an international hit. Or, it you want to listen, this Planet Money podcast about the Swiss Cheese Union.)

This is all fascinating backstory to this week's Challenge. What ELSE has been marketed as an authentic food? I put the Challenge like this:

1. What other national foods have become popular as the result of intense marketing? (I'm especially interested in foods that are presented as being "of the people," but are, in fact, commercial successes driven by clever advertising?) Can you find one or two?

I thought this might be a great question for the LLMs, and so I tried multiple attempts to get ChatGPT, Claude, and Bard to give me an answer.

I'll spare you all of the prompts I created, but basically, I got very little. With prompts like "what well-known national foods are actually the product of marketing campaigns?" I learned about marketing successes (e.g., Campbell's soups; Chiquita bananas; McDonalds hamburgers), but little about foods that are associated with particular countries (as fondue is with Switzerland).

Bard: Of the suggestions Bard made: Poutine (Canada); Big Mac (US); and Hambúrguer Artesanal (Brazil). Those are okay, I guess, but the marketing push behind each is a bit lackadaisical... nothing like the Swiss Cheese Union.

ChatGPT: Slightly better: American fast food as a category (US); Fettuccine Alfredo (Italy); Sushi (Japan)... these are all popular foods, but none that were driven by clever advertising or marketing.

One of the things that became clear to me was that I was a little ambiguous about what my SRS goal actually should be. Was I looking for well-known national foods (like poutine or Big Macs), or was I looking for national foods that reached success because of an advertising/marketing campaign?

As I often say here in SRS, you've got to be clear about what your research goal actually is so you'll know success when you see it.

Naturally, it's okay to learn-as-you-go, but at some point you have to figure out what success will mean.

I decided that I really wanted a well-known national food that became prominent internationally because of an intense marketing or advertising campaign.

What did work? Several friends wrote to me to suggest foods that they learned were market campaign-driven: SPAM, chicken tikka masala, Vegemite, and even peanut butter were all suggested as advertising-driven successes of national foods.

Reading up on these I found that:

SPAM was given a big boost by the maker, Hormel, as the result of SPAM's ubiquity during World War II. Advertising was a big component of pushing SPAM onto the global stage. (Massive distribution during World War II didn't hurt either, making SPAM incredibly popular in Oceania.)

Chicken tikka masala, while immensely popular, doesn't seem to have been driven by advertising. It's clearly a very British product that has become popular by word-of-mouth and news stories, even though it seems very Indian.

Vegemite, the intensely-flavored Australian yeast extract spread, WAS intensely marketed at the product's initial production (in the 1920s) and led to vegemite becoming a distinctly Australian food.

While peanut butter is often thought of as American, its invention is credited to three people with early patents on the production of modern peanut butter. (1) Marcellus Gilmore Edson of Montreal, Quebec, Canada, obtained the first patent for a method of producing peanut butter from roasted peanuts using heated surfaces in 1884. (2) A businessman from St. Louis, George Bayle, produced and sold peanut butter in the form of a snack food in 1894. And (3) John Harvey Kellogg (yes, THAT Kellogg) was issued a patent for a "Process of Producing Alimentary Products" in 1898 with peanuts, although he boiled the nuts rather than roasting them. There's been a fair bit of marketing, but again, nothing quite as intense as the Swiss push on fondue.

But how can we find all of these--and more!--by searching?

My first regular Google search was:

[ national dish food marketing campaign ]

which led me to a fascinating book, "National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home" by Anya von Bremzen. This is basically a compendium of the backstories of various foods, showing how sometimes national foods have a messy beginning. For instance, she points out that Andalusian gazpacho were not just simple Spanish regional foods, but dishes historically cooked across the country. She points out that La Sección Femenina, the women’s branch of Spain’s fascist movement, identified some foods (like gazpacho) with specific regions, as part of its work to create “a sanitized, politically acceptable form of cultural diversity.”

I also found the Wikipedia page on National Dishes (have to admit that I wasn't expecting this page to exist--there must be a lot of foodies among Wikipedians). Scanning that list shows a lot of national dishes, some of which I recognized as very popular.

I spot checked a bunch of them: Wiener schnitzel (Austria), empanadas (Bolivia), Peking duck (China), pot-au-feu (France) and about ten others. The nearly all of the national dishes I checked became national dishes over the course of great spans of time, without any particular interference or promotion. They really are of the land and the people.

However, two Japanese foods that are known world-wide qualify as marketing/advertising driven:

Ramen is a massive international success that was driven in the US by the introduction of instant ramen noodles (beloved by college students), and by Chef David Chang's introduction of ramen at Momofuku in New York City in 2004, driven by a clever influencer campaign. (Incidentally, Momofuku Ando was the name of the inventor of the instant ramen noodle.)

Likewise, but to a lesser extent, sushi seems to have become an international success by marketing, although that effort was a bit hodge-podge with many small pushes from multiple players rather than one large company.

I found those through friends (thanks, friends!) and by manual work from the National Dishes Wikipedia page.

But then I had the thought, what if I limited my previous search to just Wikipedia? Like this:

[ site:Wikipedia.org national dish food marketing campaign ]

What would I find?

Answer: Several additional dishes and a bunch that you can look up on your own. MY favorites from this search...

Ploughman's Lunch (Britain, marketing campaign by the Cheese Bureau and the Milk Marketing Board, shades of the Schweizerische Käseunion!)

Lamb (Australia, marketing by Meat and Livestock Australia, the MLA)

Kentucky Fried Chicken (USA, marketing by KFC, which scored a massive success in making KFC the default Christmas dinner in Japan)

Coca-Cola (USA, the Coke company has run one of the most successful marketing campaigns in history for over 100 years)

1. LLMs sometimes just don't deliver. I spent at least two hours trying to convince Bard and ChatGPT to give me something useful. And yes, I tried all of the clever prompt engineering tricks I could think of, but nothing seemed to work. Ah well... they're not the universal solution to all known problems.

2. Friends! I was happily impressed by the number of friends who had suggestions. Don't ever underestimate the value of a good social network. I got text messages from some friends who'd seen the post, some comments on my other networks (e.g, LinkedIn or Facebook), and a couple of direct emails. Ah, friends. Good to have them as an extension to my brain.

3. Wikipedia lists. I should know by now that there is a list for almost everything. National foods is not an exception to this rule. Remember to look for "list of" something when you're searching for a category.

4. Use site: over a large resource. For instance, my use of my previous search query, when restricted to Wikipedia actually helped me find a few new suggestions. Don't forget the power of limiting your search!

As we close out the year, I'm going to take a couple of weeks off and start anew in 2024. I'll be moving back from Switzerland to California in the next few days and restart my life there. It's been wonderful to explore Zürich and the Swiss countryside from a different perspective, that of someone who is new to the place--a new country to discover, what more could you ask for as a Christmas present. That's what I got, and I hope you enjoyed learning a bit about the place as much as I did.

See you in January, 2024. Have a wonderful holiday season and New Year!

Keep searching!

December 13, 2023

SearchResearch Challenge (12/13/23): What makes a national dish?

When in Switzerland,

I'm fond of fondue.

I'm fond of fondue. ... you have to have fondue.

Something I learned today….

Apparently, fondue has been around for a while, at least since 1875, when the first fondue recipe was published as a town-dweller's dish from the lowlands of the western, French-speaking parts of Switzerland.

It was popularized as a Swiss national dish by the Swiss Cheese Union (Schweizerische Käseunion) beginning in the 1930s as a way of increasing local overproduction of cheese. Too much cheese, too few cheese-eaters--the obvious fix is to figure out a way to increase local demand for local cheese.

And thus it came to pass that the Swiss Cheese Union created pseudo-regional recipes as part of the "spiritual defence of Switzerland" before World War II. After wartime rationing ended, the Swiss Cheese Union continued its marketing campaign, sending fondue sets to military regiments and event organizers across Switzerland as a way to spread the message of social cheese eating.

As a consequence, fondue is not just popular, but also now a symbol of Swiss unity. The marketing campaign successfully associates fondue with Swiss mountains, good times, and healthy outdoor winter sports.

Ever since those heady days, fondue has been promoted aggressively in Switzerland, with slogans like "La fondue crée la bonne humeur" ('fondue creates a good mood') and, in Swiss German, "Fondue isch guet und git e gueti Luune" ('fondue is good and creates a good mood') – usually abbreviated as the tongue-twister "figugegl."

Background: "History of Cheese Fondue" (Oct 29, 2009) – an interview with Isabelle Raboud-Schuele, by Gail Mangold-Vine. Originally published in www.Automnales.ch (http://www.automnales.ch/) Raboud-Schuele is the curator at the Alimentarium Food Museum in Vevey.

This is all fascinating backstory to this week's Challenge. My illusion of fondue as the simple national dish of Switzerland has been shattered. What I thought of as a regional, rustic dish of the commonfolk has been revealed to be the result of rather clever marketing.

And that thought made me wonder:

1. What other national foods have become popular as the result of intense marketing? (I'm especially interested in foods that are presented as being "of the people," but are, in fact, commercial successes driven by clever advertising?) Can you find one or two?

Of course, as always, we're deeply curious about HOW you found these other popular campaign-driven foods! Let us know!

Keep searching!

December 9, 2023

Answer: What type of paintings are these? (Swiss Mystery #4)

Curiouser and curiouser ...

A knight striding with flag, bear, and sword. (Bern, Switzerland)

A knight striding with flag, bear, and sword. (Bern, Switzerland)I'm officially a faculty member at the University of Zürich, and as such, you'd think I'd understand lots about Swiss culture. But I'm a newbie, a recent (and temporary) immigrant. I'm heading back to California at the end of the year.

But one of the great things about traveling is the chance to see the world through new eyes. Last week I posed a simple question: What are these paintings on buildings that I'm seeing everywhere in Switzerland.

In the past week I've asked several Swiss folks what they'd call these things, and surprisingly, most of them said "I don't know... paintings?" It's not something they've thought about much, they're just part of the background, they've always been there. But to me, as an outsider, see the everyday and think it's extraordinary.

Here are a few examples:

But to me, these stand out and are interesting. Since I'm a curious fellow, I had to ask the Swiss Mystery for this week...

1. Is there a name for this particularly Swiss kind of artwork-on-the-walls? Is there a particular name of the style in which most of them are drawn?

How to start?

I know that paintings on walls are often called frescos, so:

[ Swiss frescos ]

actually didn't work all that well. I found a couple new ones, but the new paintings I found were mostly interior frescos (a la the Sistine Chapel in Rome, probably the world's best known fresco). So it's pretty clear they're not called that. My next search:

[ Switzerland painting on exterior of buildings ]

worked a bit better. This led me to find that many people used the word "facade" with these paintings. My next query:

[ Switzerland facade painting ]

returned results that were pretty good. There were many more "Swiss exterior paintings" in the Images collection, but I still don't have a collective noun for these things. Besides, "facade" means "the principal front of a building, that faces on to a street or open space," which is nice, but it doesn't describe the paintings per se, but just where they're located.

On the other hand, this results page points to some great collections of these paintings. One of these links is to the wonderful paintings on buildings in Schaffhausen:

https://www.swiss-spectator.ch/fassad...

I put the full text of the link there because I noticed something odd. See that term in the URL "fassadenmalerei"? I don't know it... could it be a clue?

If you do a search on:

[ fassadenmalerei ]

you'll find a lot of sponsored links--ads for companies that paint the facades of buildings. The German word "fassaden" means "facades" and "malerei" means "painter," specifically of decorative paintings. So this makes sense--of course there are companies that will paint your facades, usually in elaborate geometric color schemes.

I looked at a few of their sites just to get a sense for the kind of work they do. Do any of them do paintings of the shown above?

The fourth site I looked at does something they call "wand-und-fassadenmalerei." Since "wand" means "wall," maybe we're getting a little closer. Their demo images include some of the type we seek.

While reading a few of these sites, I found another word that seems on our trail: "Lüftlmalerei." A quick search for:

[ Lüftlmalerei ]

takes us to the German Wikipedia entry, Lüftlmalerei, which tells us that

"... Lüftlmalerei (also spelled Lüftelmalerei ) refers to the art form of facade painting native to small towns and rural areas in southern Germany and Austria, especially in Upper Bavaria (Werdenfelser Land) and in Tyrol."

Well, that's interesting.

The region of Tyrol is in the far western part of Austria, bordering eastern Switzerland. Southern Germany is to the north and east of Switzerland, so it's definitely in the area.

Interestingly, when I asked my Swiss friends about this word, Lüftlmalerei, they mostly said they understood it as "air painting," and that it sounded somewhat familiar, but they also all said "it sounds like an Austrian word." (Apparently that second L, lüftlmalerei, gives it that uniquely Austrian sound.)

Looking at lüftlmalerei images shows us that this seems like the right word:

Some SRS Regular Readers wrote in (on one of our parallel syndications) about this Challenge.

Regular Reader Bill Janssen just knew that the word was probably “Wandmalerei." As we saw, that's certainly part of the answer.

Franz Miltner (who works in Ingelheim am Rhen) says “Not sure if there is a different term in Switzerland, but it's Lüftlmalerei in southern Germany and Austria."

Perhaps most notably, Regular Reader SpiritualLadder points out that:

You might not like this, but I literally put in your exact question with the image into ChatGPT and this is what I got:

(ChatGPT reply): "The artwork depicted in the image you've provided is reminiscent of a mural. In Switzerland, such murals are often associated with a long tradition of public art and can be reflective of various styles, from classical frescoes to more modern interpretations.

Specifically, in Switzerland and parts of Germany, there is a tradition known as "Lüftlmalerei," a style of mural painting that is particularly found in the alpine regions. This style often features pastoral scenes, historical figures, and local legends, and is characterized by its use of vibrant colors and intricate details to create a sense of three-dimensional space on flat surfaces."

To SpiritualLadder's point, it doesn't bother me at all that ChatGPT was able to provide such a good answer--this is a real improvement!

When you google Lüftlmalerei, you find that it is present in Germany and Austria, so it sounds like it might not be the right answer, but they do look similar to the ones you posted...so it feels right. (Maybe it has a different Swiss name.) If it *is* the right answer, that would explain why it's hard to find!

I felt like ChatGPT (with vision) *might* be able to handle this kind of task well since it might have been trained on images of this style. The first time I prompted it with a different wording it wasn't as helpful, but putting in your exact question got me this answer!

As I've noted before, the LLMs are still subject to hallucinations, so you still need to check everything. But if this accelerates the search process for some Challenges, I'm all for it.

SearchResearch Lessons

The traditional way I did it illustrated some insider techniques.

1. Don't ignore the URLs. They sometimes contain clues that will help you find the result you're looking for.

2. Read related sites while looking for terms and concepts you don't know. Reading related websites is how I learned about the idea of Lüftlmalerei, quickly doing a couple of searches to validate that this is, in fact, the correct term.

3. Don't ignore the LLMs. As SpiritualLadder points out, the LLMs can sometimes do a great job of pointing out things that you might not have considered. Be sure to validate the results they give you, but they're getting better every day. Consider checking AND confirming!

Keep searching!

November 29, 2023

SearchResearch Challenge (11/29/23): What type of paintings are these? (Swiss Mystery #4)

As I wander over hill and through dale, through alpine passes and mountain streams...

A knight striding with flag, bear, and sword. (Bern, Switzerland)

A knight striding with flag, bear, and sword. (Bern, Switzerland)... I'm seeing a kind of exterior artwork on the outside walls of many Swiss buildings. This is such a common thing that surely there must be a specific name for these kinds of paintings that appear on the buildings. Sometimes they're old, sometimes relatively new. Some fancy, but most are stylized in a way that I cannot describe easily--they're often noble, or heroic, frequently bucolic, sometimes civic in design, almost always in a kind of flattened, non-realistic rendering.

The Swiss Mystery for this week is this...

1. Is there a name for this particularly Swiss kind of artwork-on-the-walls? Is there a particular name of the style in which most of them are drawn?

I admit that I do not know the answer yet, but I feel as though there MUST be a rather specific term for these images on the walls of greater Switzerland.

Here are a few examples:

What do you call these? More importantly, what do the LOCALS call this kind of artwork?

I'd like to learn more about this artistic tradition, but don't know quite where to start. Any ideas from the SearchResearch crowd?

When you find the answer(s), let us all know HOW you found them! Let notes in the comments field.

Keep searching!

November 21, 2023

Answer: How does it work? Checking your assumptions?

We all make assumptions...

... it's a normal thing to do. But when we're doing online research, it's good to check yourself. This week's Challenge is a little story about why...

My assumption was that these common kitchen appliances had the same mechanism for knowing when the toast / water / rice is at the right temperature or level of doneness.

Then I checked--and had a big surprise. Really?

Today's SearchResearch Challenge is simple:

1. So... how DO each of these devices know when the toast / water / rice is ready?

2. (extra credit) What other devices do you believe you understand, but when you checked, you learned that you actually didn't understand? Does anything spring to mind? Any surprises?

Searching for the answer isn't hard:

[ how does an electric tea kettle know when

the water is boiling ]

[ how does a rice cooker know when

the rice is done ]

[ how does a toaster know when

the toast is done ]

Let's talk about these one-by-one.

Electric tea kettle: Do this query and you'll find a lot of explanatory text telling you that a ring-shaped bimetallic strip changes shape as it warms up, and since it's slightly buckled, when it deforms just enough, it snaps into a different shape, mechanically flipping the heater switch to off when the water hits the boiling point of 100C (212F). Very simple, very clever. But how does it know?

The underside of a tea kettle with the bimetallic ring outlined with a red dashed line.

The underside of a tea kettle with the bimetallic ring outlined with a red dashed line. That bimetallic ring is actually a fairly smart little invention--the tang coming out of the ring lies in the plane of the ring at room temperature, but as the ring starts to bend under the heating of the kettle, it suddenly snaps to a different shape with the tang pointing up. This is called a bistable device, a gizmo that can be in one of two different physical configurations. Of course, the bimetallic strip's clever trick is that it will flip into the "hot" state when the temperature gets high enough, then flip back to the cool state after the heat is off. That rapid flip to the other bistable position is what mechanically flips the power switch back off.

The best example of this I could find is this YouTube short showing a tea kettle thermostat that flips back and forth rapidly when warmed up. (Video link.)

And... I thought that was that.

But as I was writing this up, I ran across a video about electric tea kettles on Steve Mould's YouTube channel that showed me something I'd completely missed: the steam tube!

(Steve Mould video short on steam tubes in tea kettles.)

It turns out (as Steve Mould points out), that the thermostat is actually at the bottom of the tube that is open to the top of the vessel. As the kettle heats up, eventually the steam in the kettle is forced down the tube where it directly heats up the thermostat, which flips at around 95 C (203 F).

Why is this important? Because water boils at different temperatures at different altitudes, so a thermostat that is preset to 100C won't switch off at high altitudes. In Denver, which is at 1609 meters (5280 feet), water boils at 95°C, or 203°F. So if the thermostat only tripped at 100°C, it wouldn't work!

At this point I got really curious about this somewhat sophisticated design, so I looked up a few electric tea kettle patents, where I learned that this is well-known by tea kettle designers. To quote one such patent (US4357520, from 1979):

"Alternatively a steam tube or passage, which communicates with a steam or vapour aperture in the upper wall of the container, may be run down the outside of the container. Such a tube or passage may be concealed within or behind a handle structure of the container..."

I thought that was it. NOW I understood how they worked.

But as I was writing this up, on a lark, I searched for:

[ electric tea kettle diagram ]

hoping to find a cross-section of a kettle showing the steam tube.

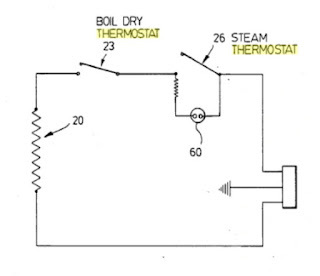

But NO! I was again surprised to learn that there is a second thermostat, a "boil dry" thermostat that kicks in if/when the first thermostat fails to detect any steam. This would happen if the kettle was switched on without any water. No water, no steam, no steam pressure, no thermostat clicking off.

I found this because I saw this diagram in the search results:

Electric tea kettle circuit diagram. (P/C from Karisimby's blog)

Electric tea kettle circuit diagram. (P/C from Karisimby's blog)I know enough about electronics to realize that this was NOT what I had in my head. The "steam thermostat" was what I expected. What I did not expect was a second "Boil dry" thermostat.

A bit more searching revealed that such a second thermostat is set at a much higher temperature and is attached directly to the kettle wall. So if the kettle is dry and heating up, the steam thermostat won't kick in, but the boil dry thermostat will open the circuit and stop the heating from running away (and possibly causing a meltdown).

Amazing what you'll learn if you keep poking. (If you want to learn more, I recommend this wonderful explanation of tea kettles.)

Rice cooker: Again, not a difficult query, but the answer surprised me! I'd assumed that there was a simple bimetallic thermostat in the rice cooker as well--in fact, I'd assumed that it worked in much the same way, probably with an identical part inside.

But I quickly learned that most rice cookers (especially older ones) use a very clever magnet that turns off the heating element when the temperature goes above 100°C, or 223°F.

Basically, there are two heaters in a rice cooker--one that keeps the rice warm and a second heater that boils the water, much like the tea kettle.

However, I learned that rice cookers have a little magnet that holds the switch closed to close the main circuit to the heating element. That circuit heats up the water until it boils, after it boils, the temperature of the magnent will start to rise beyond 100°C, or 223°F. When that happens, the magnet loses it's magnetism, allowing the circuit breaker to pop open, stopping the heating.

The amazing trick here is that the magnet is designed so that it's Curie point (that is, the temperature at which it loses its magnetism) is at 100°C!

This is simpler to watch a video than to explain in text. So I recommend this video: Nice explanation of how the magnetic cutoff switch works on a rice cooker.

The bimetallic strip thermostat works because different metals expand at different rates, causing it to change shape.

I didn't dream that using a magnet's Curie temperature would be used in the simplest of all rice cookers. It's really not obvious that this is would be used to turn off the heat. Incredibly smart use of some sophisticated physics.

Oddly, I can't find any evidence that a rice cooker has a boil dry mechanism! (I assume they do. If you find out, let me know in the comments below.)

To be sure, there are other mechanisms out there for telling when the rice is done--neural fuzzy logic rice cookers with complicated sensing systems. But I love this elegant application of magnets!

Toaster: The big problem with toasters is that there are so many of them. But for the most part, simple toasters are just timing mechanisms... turn the dial, get the level of brown you'd like. It's really up to you learn which dial setting corresponds to the level of toasted that you like.

But there are a LOT of different toasters out there--some with fancy thermocouples to determine temperature, some with just plain old spring-loaded timers that count down the seconds, and some with complex electromagnets to hold down the carriage (that carries the bread/toast on its journey).

The old-fashioned toaster, though, is just a timer... nothing more than that.

Other devices I don't understand?

2. (extra credit) What other devices do you believe you understand, but when you checked, you learned that you actually didn't understand? Does anything spring to mind? Any surprises?

There are LOTS of things I don't understand, but will look into once I get the chance. I want to learn how the magic happens. Among them,

1. iPhone--how it knows how far I've walked or run. I know it counts steps, and I know it has a GPS system in it, so I assume it uses the GPS for distance traveled and counts steps via the on-board accelerometers, but does it combine those information streams in some way? Don't know.

2. Refrigerators--I don't understand the physics of them in detail, but I do know that they have a single cooling unit which then cools the frozen foods at one temperature, but the cool part of the fridge is handled in a different way. Again, how does it know?

3. Sauté release--Sometimes when I cook (say) a piece of meat, it will come out of the pan easily--it "releases" with ease. But sometimes, it sticks and makes a mess. Is it purely a function of temperature, the amount of oil, or the material in use? I need to understand this!

The bigger point here is that all of these phenomena are understandable with a little observation and a dash of SRS.

SearchResearch Lessons

1. Expect surprises and be ready for them. Initially I thought that the rice cooker story was going to be straightforward. So it was a surprise when the story got more complicated. I discovered that when I noticed that something I read from the SERP didn't fit in with what I already knew. (And this happened to me twice!)

2. Use multiple document types to get a full perspective. Sometimes a regular web search works just fine, but for complicated searches like the rice cooker, I used Image search, YouTube searches, and even Patent searches to get multiple perspectives. I ALSO looked at multiple sources for each device, partly because some of the documents are simplified versions. (For instance, not all rice cooker stories mention either the steam tube OR the dry boil cutoff thermostat.)

3. Be aware when what you read doesn't match what you think you know. Again, this happens multiple times for every SRS session--I learn things, and then learn something different. When what you read doesn't line up with what you've already read, take that as a signal that there's more to learn!

And keep searching!

November 8, 2023

SearchResearch Challenge (11/8/23): How does it work? Checking your assumptions.

The most common error...

... in online research is probably that of not checking your assumptions. We tend to see the world without questioning, and we often bake those assumptions into our research behaviors.

Here we see three common, everyday appliances: an electric tea kettle, an ordinary rice cooker, and a plain old toaster.

I've seen these for years--there's nothing especially strange or exotic about them. You've probably used them all as well.

As I was waiting for my toast to turn to a satisfactory shade of brown, I was looking at it standing next to my electric tea kettle, not far from my rice cooker and thinking about how they each know that the toast / water / rice is ready.

My assumption was that they all had the same mechanism for knowing when the toast / water / rice is at the right temperature or level of doneness.

So I was really surprised when I checked my assumption, and found that I was utterly wrong. The only device that I got right was the toaster--I knew that one--the other two surprised me.

Today's SearchResearch Challenge is simple:

1. So... how DO each of these devices know when the toast / water / rice is ready?

2. (extra credit) What other devices do you believe you understand, but when you checked, you learned that you actually didn't understand? Does anything spring to mind? Any surprises?

This SRS Challenge isn't that hard, but it brings up a fairly deep point about when to question our assumptions... and HOW to realize that your assumptions might be wrong. Any ideas?

Share your thoughts in the comments.

Keep searching!

October 31, 2023

Answer: Three little Swiss mysteries?

Living anywhere new inevitably leads to discoveries and recognition that the world is larger and more interesting than you might have thought,

As mentioned, I'm here in Switzerland for four months. Even though I've been here before many times, the extended time period of living in one distinctly different place is proving to be eye-opening.

But as a person who's relatively new to life in Zürich, I've found a few things that are charming and puzzling at the same time. Can you help me figure out what's going on in each of these cases?

1. Why are these eggs colored orange/yellow? I bought them in the local grocery store where they were sitting out on the shelf, unrefrigerated. The label on the container says Schweizer Eier (Swiss eggs). I've seen many different colored eggs from friends who have chickens (blue, green, brown, some with spots), still, this is extraordinary color. But what's the story here? What kind of chicken would produce these eggs?

I was thinking that these eggs were naturally this color. After all, eggs DO come in a bunch of different colors! I knew that, in the US at least, chicken eggs can show up in a variety of shades:

Photo by Justin Pius, NRCS

Photo by Justin Pius, NRCSSo I was prepared to think that maybe Swiss chickens are simply more colorful!

I spent a lot of time searching for colored eggs, learning that I needed to include chicken in my searches, as there are a wild number of different kinds of eggs from a zillion kinds of birds, some of which are extraordinary. (See the Science News article about different egg colors.)

I also have to admit to spending at least 30 minutes poking around looking at many pages, and NOT finding anything. Oh, I found a lot, but the colored eggs made at Easter, or the tendency to have naturally dyed eggs were all over the results. Here's a sample of what I was seeing:

I was just scrolling around, trying to figure out what to do when I noticed one article about Look! Colored Eggs in Swiss Supermarket. That's what I was looking for! But in the article, it mentioned that "colored eggs... are so nice for picnics." Huh? You wouldn't take raw eggs on a picnic, right?

So I changed my query to a question using that as inspiration: [ Why are there colored eggs in Swiss supermarkets? ]

And very quickly learned from a Reddit post that "In Switzerland, grocery stores sell painted hard-boiled eggs in order to differentiate between the fresh and hard-boiled ones." (SRS tip: Google is much, much better at answering free-form questions, independent of the LLM work.)

Now Reddit is fun, but a bit untrustworthy. However, when I double-checked, I found multiple sources telling me this. Grocery stores in Switzerland DO sell hard-boiled eggs in a variety of colors (these red/gold eggs are from one particular store--different store will have different colors)!

I checked on the package that held the eggs and found (in fairly small font!) that they are "Aus Freilandhaltung * gekocht * gefärbt." I should have looked more carefully. Google Translate tells me that this means "Free range * cooked * colored."

Ah. Got it.

Lesson learned: Read the package (even the small print) first. Also learned that sometimes you'll learn the crucial tip by just scanning the results!

2. While on a hike in the Alps (near Rigi Scheidegg, if that helps), I came across this flag--and I have no idea what kind of a flag this is. What does it represent? (It might help to know that the Swiss are a little flag-crazy. There is traditional Swiss flag-tossing (a kind of bucolic, even serene sport... watch the video), and flags seem to abound. Given the level of vexillological interest here, it must signify something, but what?

This has turned out to be very hard--I'm not sure I have the right answer. I tried all of the obvious image search tools (Google Image Search / Lens; Tineye; Bing Image Search; Yandex Image Search), but none of them gave me anything good.

I tried various descriptions of the flag (four white hearts, four-leaf clover on a red background, etc etc.), but nothing really worked. I searched for versions of these terms with words like "logo" or "flag" or "emblem" or "sigil" or "device"... but I didn't get very fair. SRS Reader Paul L tried the specific flag search engine FlagID.org (that's a new one to me.. nice find Paul), but to no avail.

I figured it was a cantonal flag or arms--but I checked those as well--no dice.

Paul also "... finally loosened the search to only include red flag with white and scanned to see the much sharper edges of the Maltese cross on the Bardonnex Commune (Switzerland) flag." While that's really close, it's not quite the same thing.

I even made a fairly high-resolution image of the flag and tried to Google Lens (and Bing, and Tineye) this:

But this didn't really work either. I found some near hits:

- a UK company called Schmecken that has a logo very much like this:

- a Finnish group on Twitter/X called Pohjois-Pohjanmaa for social and health security association:

- a car company, Autoclover:

But nothing that was flag-like and Swiss. Is it possible that this is a one-off custom flag?

Then I was walking down the street in the town of St. Gallen (in northern Switzerland) and saw this stand-up box advertising the Swiss national lottery, Swisslos:

Which is the closest Swiss 4-lobed clover-like bit of iconography I can find. (Later I went back and looked deeper in my search-by-image results and found the Swisslos logo. Always go deeper.)

But it's not an exact match. People who make flags are pretty picky about the details of their design. (See the brilliant Roman Mars TED talk about flag design. 18 minutes that will change the way you look at flags.)

So I'm not convinced we know the answer. We're going to have to leave this as an open Challenge for the moment. I'll keep looking, and you, my Regular Readers, should do the same. IF you see it, post a comment here so we'll all know what it actually is. (And I, for my part, if I go back to that part of the Alps, I'll find the owner and ask!)

3. I've seen some interesting vegetables before in farmer's markets before, but this one seems very Seussian to me. What ARE these things? How would I eat one?

This one was easy: looks like a weird cabbage, smells like a cabbage, so my query was:

[ cone shaped cabbage ]

Which rapidly told me that this cabbage has a number of names: conehead, pointed, arrowhead, and sweetheart cabbage. It's described as having "... leaves, with variations of pea green colorings, are thin, broad, deeply veined, tightly enveloped lengthwise and bluntly pointed. The flavor of Conehead cabbage is mild and remarkably sweet, void of that bold cruciferous flavor that is most reminiscent of cabbage."

Naturally, I bought one for research purposes and ate it for most of the week. It is, indeed, sweetly flavored and is a lovely thing to have on your plate. (I just sautéed/steamed mine with a little olive oil, garlic, and salt. Yum!)

1. Mind your assumptions! In the colored egg Challenge I had assumed that the eggs in question were naturally colored like that. I was prepared to learn that Swiss chickens are some interesting breed that lay technicolor eggs. It took me a while to undo that assumption and figure out that they're dyed eggs.

2. Even unreliable sources can be useful. I found that Reddit post about hard-boiled Swiss eggs to crack the case (so to speak), but I know that Reddit can be unreliable. So when I checked, I was pleased to find MANY sources confirming that colored eggs are hardboiled, just like this detective.

3. Read the fine print. I skipped the fine print on the package partly because it was small and partly because it was in German, and while I can read lots of German, I didn't know what Aus Freilandhaltung meant, so I stopped reading. FWIW, I know what gekocht and gefärbt mean... but I'd stopped reading too early.

4. Some Challenges don't come easily. The identity of the flag has not yet been cracked! It's an open case. Sometimes, that's the way it goes.

Keep searching!

October 24, 2023

SearchResearch Challenge (10/25/23): Three little Swiss mysteries?

I'm currently living and teaching in Zürich until the end of the year,

.. here in the heart of Switzerland. I'm teaching for this semester at the University of Zürich--and you only get one guess as to what I'm teaching. That's right, I'm here to teach the course on Human-Computer Interaction and AI over the 14-week semester.

(In other words, what should we be doing to design and build AI systems so that people can understand and use them. Hence last week's Challenge about getting LLMs to be useful in search tasks.)

But as a person who's relatively new to Switzerland, I've found a few things that are charming and puzzling at the same time. Can you help me figure out what's going on in each of these cases?

1. Why are these eggs colored orange/yellow? I bought them in the local grocery store where they were sitting out on the shelf, unrefrigerated. The label on the container says Schweizer Eier (Swiss eggs). I've seen many different colored eggs from friends who have chickens (blue, green, brown, some with spots), still, this is extraordinary color. But what's the story here? What kind of chicken would produce these eggs?

2. While on a hike in the Alps (near Rigi Scheidegg, if that helps), I came across this flag--and I have no idea what kind of a flag this is. What does it represent? (It might help to know that the Swiss are a little flag-crazy. There is traditional Swiss flag-tossing (a kind of bucolic, even serene sport... watch the video), and flags seem to abound. Given the level of vexillological interest here, it must signify something, but what?

3. I've seen some interesting vegetables before in farmer's markets before, but this one seems very Seussian to me. What ARE these things? How would I eat one?

Of course, we want to know how you found the answers to each Challenge. Share your search tricks with us!

Keep searching!