The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Doctor Zhivago

RUSSIA

>

DR ZHIVAGO - HF - GLOSSARY (SPOILER THREAD)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Joanne wrote: "If you are looking for an accessible survey of Russian History, consider the Teaching Company course: "History of Russia: From Peter the Great to Gorbachev" by Prof. Mark D. Steinberg.

Joanne wrote: "If you are looking for an accessible survey of Russian History, consider the Teaching Company course: "History of Russia: From Peter the Great to Gorbachev" by Prof. Mark D. Steinberg.http://www.t..."

Thanks that looks so great - if it weren't quite so pricey - I took a course on the history of Russia in college - many many moons ago - and it was so terrific - I don't know how much I remember - :-(

Becky wrote: "Joanne wrote: "If you are looking for an accessible survey of Russian History, consider the Teaching Company course: "History of Russia: From Peter the Great to Gorbachev" by Prof. Mark D. Steinber..."

Becky wrote: "Joanne wrote: "If you are looking for an accessible survey of Russian History, consider the Teaching Company course: "History of Russia: From Peter the Great to Gorbachev" by Prof. Mark D. Steinber..."These courses always go on sale. Titles are rotate. So watch for sales. Also, my public library has many titles.

I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)

I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)

This outline of the chronology of "Doctor Zhivago is from "Doctor Zhivago in the Post-Soviet Era: A Re-Introduction" an essay in Doctor Zhivago: A Critical Companion edited by Edith Crowes. It's basically a chapter-by-chapter dates and places review. (NOTE: there are some spoilers!)

This outline of the chronology of "Doctor Zhivago is from "Doctor Zhivago in the Post-Soviet Era: A Re-Introduction" an essay in Doctor Zhivago: A Critical Companion edited by Edith Crowes. It's basically a chapter-by-chapter dates and places review. (NOTE: there are some spoilers!)  by Edith W. Clowes (no photo)

by Edith W. Clowes (no photo)Chapter 1 :October 1901 - burial of Yuri's mother

summer 1903 - at Kologrivov's estate

Chapter 2: October 1905 - Moscow rail workers' strike, suppressed by Cossacks

December 1905 - Moscow Presnya neighborhood revolt

Chapter 3: Christmas 1911 - winter 1912 - Moscow, Sventitsky's party

Chapter 4: spring 1912 - Moscow - departure of Lara and Pasha for Yuryatin

1915 - Yuriatin, Pahsa leaves for the front, Yurii at front in Galicia

February 1917 - at the front

Chapter 5: summer 1917 - "republic" of Zybushino,

August 1917 - Yurii leaves for Moscow

Chapter 6: late summer 1917 - Moscow

October 1917 - Bolshevik Revolution

Winter 1917-18 - Moscow

Chapter 7: March 1918 - trip to the Urals

Chapter 8: spring, early summer 1918 - arrival at Varykino

Chapter 9: winter-spring, 1918-19 - Varykino

Chapter 10: 1919 - Western Siberian villages on the road

Chapter 11: 1919, fall 1920 - Western Siberia

Chapter 12: all 1920, winter 1920-21 - Western Siberia, Yurii's trek to Yuriatin

Chapter 13: spring-summer 1921 - Yuryatin

Chapter 14: winter 1921 - Varykino -Lara's departure for Siberia

Chapter 15: 1922-29 - Yurii's trek back to Moscow (New Economic Policy), Yurii's death

Chapter 16: 1943 - camp during World War II.

"Five or ten years later": Moscow - Misha and Nika read Yurii's notebooks.

Chapter 17: poem cycle

***

Becky wrote: "I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)"

Becky wrote: "I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)"I have enjoyed The Great Courses for many years. The sales rotate and in the course of a year most (all?) of the titles go on sale. I've never been disappointed. The professors at tops in their field as scholars and are also rated as great "teachers."

Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25

Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25 Summer-Fall 1960

Interviewed by Olga Carlisle

http://www.theparisreview.org/intervi...

Good article - interview with Pasternak - much more at the site. Here are some relevant snips:

“As you can imagine, some of the letters I get about Doctor Zhivago are quite absurd. Recently somebody writing about Doctor Zhivago in France was inquiring about the plan of the novel. I guess it baffles the French sense of order. . . . But how silly, for the plan of the novel is outlined by the poems accompanying it. This is partly why I chose to publish them alongside the novel. They are there also to give the novel more body, more richness. For the same reason I used religious symbolism—to give warmth to the book. Now some critics have gotten so wrapped up in those symbols—which are put in the book the way stoves go into a house, to warm it up—they would like me to commit myself and climb into the stove.”

****

“These poems were like rapid sketches—just compare them with the works of our elders. Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy were not just novelists, Blok not just a poet. In the midst of literature—the world of commonplaces, conventions, established names—they were three voices which spoke because they had something to say . . . and it sounded like thunder. As for the facility of the twenties, take my father for example. How much search, what efforts to finish one of his paintings! Our success in the twenties was partly due to chance. My generation found itself in the focal point of history. Our works were dictated by the times. They lacked universality; now they have aged. Moreover, I believe that it is no longer possible for lyric poetry to express the immensity of our experience. Life has grown too cumbersome, too complicated. We have acquired values which are best expressed in prose. I have tried to express them through my novel, I have them in mind as I write my play.”

****

“When I wrote Doctor Zhivago I had the feeling of an immense debt toward my contemporaries. It was an attempt to repay it. This feeling of debt was overpowering as I slowly progressed with the novel. After so many years of just writing lyric poetry or translating, it seemed to me that it was my duty to make a statement about our epoch—about those years, remote and yet looming so closely over us. Time was pressing. I wanted to record the past and to honor in Doctor Zhivago the beautiful and sensitive aspects of the Russia of those years. There will be no return of those days, or of those of our fathers and forefathers, but in the great blossoming of the future I foresee their values will revive. I have tried to describe them. I don’t know whether Doctor Zhivago is fully successful as a novel, but then with all its faults I feel it has more value than those early poems. It is richer, more humane than the works of my youth.”

Becky wrote: "Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25

Becky wrote: "Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25 Summer-Fall 1960

Interviewed by Olga Carlisle

http://www.theparisreview.org/intervi...

Good article - inte..."

Nice addition. Thanks!

Joanne wrote: "Becky wrote: "I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)"

Joanne wrote: "Becky wrote: "I have two (!) other friends who have mentioned these courses to me. I think I'm going to have to cave! (g)"I have enjoyed The Great Courses for many years. The sales rotate and i..."

I agree. Their music courses are great for amateur music types like me. I wish they had an 'App', though, as Audible does. I also have a few DVDs of theirs on Art and Architecture. Always well done, and as you said, they all eventually go on sale. I am going to have to keep my eyes open for the History of Russia. Thanks.

Edmund Wilson was one of the really preeminant literary critics of the 20th century and his 1959 article, Legend and Symbol in "Doctor Zhivago" has been regularly noted in analyses ever since. Wilson also wrote To the Finland Station, a classic now, about the historical roots of socialism through Lenin's arrival in St. Petersburg

Edmund Wilson was one of the really preeminant literary critics of the 20th century and his 1959 article, Legend and Symbol in "Doctor Zhivago" has been regularly noted in analyses ever since. Wilson also wrote To the Finland Station, a classic now, about the historical roots of socialism through Lenin's arrival in St. Petersburg http://www.unz.org/Pub/Encounter-1959...

Thank you for the heads up, Frank!

by

by

Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson

Becky wrote: "Edmund Wilson was one of the really preeminant literary critics of the 20th century and his 1959 article, Legend and Symbol in "Doctor Zhivago" has been regularly noted in analyses ever since. Wi..."

Becky wrote: "Edmund Wilson was one of the really preeminant literary critics of the 20th century and his 1959 article, Legend and Symbol in "Doctor Zhivago" has been regularly noted in analyses ever since. Wi..."Smiling. I had "To the Finland Station" in a college course.

by

by

Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson

I'm ready to get out the samovar and enjoy a cup (or two) of Russian Caravan tea. Thanks, Becky!

I'm ready to get out the samovar and enjoy a cup (or two) of Russian Caravan tea. Thanks, Becky!http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_...

I think it will be interesting to read the poetry at the end of the book. I've never really "read" it, not carefully. I feel like I'm well enough versed in the book now to appreciate them - well- maybe. I'm curious for sure. I know there is one called Mary Magdalene, and with the Chapter 12 (Rowan Tree) discussion I got really curious.

I think it will be interesting to read the poetry at the end of the book. I've never really "read" it, not carefully. I feel like I'm well enough versed in the book now to appreciate them - well- maybe. I'm curious for sure. I know there is one called Mary Magdalene, and with the Chapter 12 (Rowan Tree) discussion I got really curious.

Another item we have not discussed is the movie. I had never seen it although I was in my mid-teens when it came out. My parents loved it. And I haven't seen a movie in any form since 1999 because I tend to just fall asleep.

Another item we have not discussed is the movie. I had never seen it although I was in my mid-teens when it came out. My parents loved it. And I haven't seen a movie in any form since 1999 because I tend to just fall asleep. That said, I got Doctor Zhivago from the library and watched. I felt that some parts were really well done, other parts a travesty, and occasionally there was a part which so 1965 ( dated).

What did you all think of the film?

Becky wrote: "I think it will be interesting to read the poetry at the end of the book. I've never really "read" it, not carefully. I feel like I'm well enough versed in the book now to appreciate them - well- m..."

Becky wrote: "I think it will be interesting to read the poetry at the end of the book. I've never really "read" it, not carefully. I feel like I'm well enough versed in the book now to appreciate them - well- m..."I haven't read the poetry yet. I am trying to read without reading ahead (don't ask me why; I don't really know) but now that you mention the Mary Magdalene poem I am just going to have to. Very interesting.

Becky wrote: "There are many who think the poems should have been incorporated ... ?"

Becky wrote: "There are many who think the poems should have been incorporated ... ?"Yes. Absolutely. What do we think is behind the decision to isolate them after the novel's conclusion?

I think Zhivag's poems are at the end because we are to read them as Misha and Dudorov are said to be reading them in the preceding pages. They are not privy to Zhivag's life as we, the readers are. I suppose because of that, they are to be read for their aesthetic experience alone. ??

I think Zhivag's poems are at the end because we are to read them as Misha and Dudorov are said to be reading them in the preceding pages. They are not privy to Zhivag's life as we, the readers are. I suppose because of that, they are to be read for their aesthetic experience alone. ??Also, the poems' placement at the end means that Zhivago's spiritual life does not end. The book begins and ends with "Eternal Memory," not death.

About Pasternak's relationship with Stalin, I found the following in a rather lengthy article in a Russian studies archive:

About Pasternak's relationship with Stalin, I found the following in a rather lengthy article in a Russian studies archive:He, the living, by Michael Weiss

On the vision of Boris Pasternak.

https://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/cgi-bin/we...

"In Koryakov’s view, Pasternak was indebted both to chance and to the

numinous serendipities he favored in Doctor Zhivago. When Stalin’s wife N.

S. Alliluyeva committed suicide in 1932, an obsequious letter of condolence,

signed by thirty-three prominent Soviet writers—all of them subsequently

executed in the Great Terror—was sent to the Kremlin. Pasternak was offered an opportunity to add his signature but declined, instead choosing to append a postscript to the letter saying:

"I had been thinking, the evening before, deeply and persistently of

Stalin; for the first time from the point of view of the artist. In the

morning I read the news. I was as shaken as if I had been present, as if I

had lived it and seen it.

"Koryakov posits that this cryptic postscript, as well as Pasternak’s courageous refusal to sign the more perfunctory and toadying letter, had a

strange effect on Stalin. One needn’t take the point further, as Koryakov

does, and claim that Stalin viewed Pasternak as some sort of mystic or “dervish,” to appreciate that Asiatic tyrants inspired fear not by being

consistent in their choice of victims but by being capricious."

(more about a variety of related issues at the site)

Back to the Rowan tree: I found this link, and although it is British, it references the Rowan tree as the source of Woman (Man being made from an Ash tree) - so the tree as 'Eve' might play into this as well, but perhaps I am carrying it too far. The image of Zhivago grasping the branches of the tree as Lara has to have some sort of symbolism, though.

Back to the Rowan tree: I found this link, and although it is British, it references the Rowan tree as the source of Woman (Man being made from an Ash tree) - so the tree as 'Eve' might play into this as well, but perhaps I am carrying it too far. The image of Zhivago grasping the branches of the tree as Lara has to have some sort of symbolism, though. http://www.treesforlife.org.uk/forest...

There is also some vague Celtic belief that it leads to immortality. How any of this relates to Pasternak, I am not sure.

I think immrortality very surely does relate to Dr. Zhivago in the idea of a resurrection and the seasonal cycle of spring. Thanks for the idea.

I think immrortality very surely does relate to Dr. Zhivago in the idea of a resurrection and the seasonal cycle of spring. Thanks for the idea.

G wrote: "Back to the Rowan tree: I found this link, and although it is British, it references the Rowan tree as the source of Woman (Man being made from an Ash tree) - so the tree as 'Eve' might play into t..."

G wrote: "Back to the Rowan tree: I found this link, and although it is British, it references the Rowan tree as the source of Woman (Man being made from an Ash tree) - so the tree as 'Eve' might play into t..."What a lovely idea, G! The fact that this is a Rowan tree is so definite, so explicit. It has to mean something and Pasternak was using that type of legend/symbol in the Ural parts. The article also mentions the Norse ideas.

Becky wrote: "Another item we have not discussed is the movie. I had never seen it although I was in my mid-teens when it came out. My parents loved it. And I haven't seen a movie in any form since 1999 because ..."

Becky wrote: "Another item we have not discussed is the movie. I had never seen it although I was in my mid-teens when it came out. My parents loved it. And I haven't seen a movie in any form since 1999 because ..."In contrast to the book, in the movie (which in my opinion was largely a love story), the characters were overly earnest. The rather grave countenance of everyone is not unlike early Russian cinema, and I give Lean credit for bringing that dour characteristic forward.

I think what is tragedy in the book translates to earnestness in the movie.

G wrote: "I think what is tragedy in the book translates to earnestness in the movie.."

G wrote: "I think what is tragedy in the book translates to earnestness in the movie.."In addition to the film (anniversary video edition of the movie) I saw a documentary related to it. In the documentary portion, the "host" (?) said that David Lean wanted Zhivago portayed as "dreamy."

I think Lean was right to go for that, but it didn't come off in the film too well, not to me, anyway. To me, Shariff just looked love-struck and lost. (But I'm NOT a big movie-goer, much less a critic.)

Becky wrote: "G wrote: "I think what is tragedy in the book translates to earnestness in the movie.."

Becky wrote: "G wrote: "I think what is tragedy in the book translates to earnestness in the movie.."In addition to the film (anniversary video edition of the movie) I saw a documentary related to it. In the..."

I vividly remember seeing "Dr. Zhivago" on its initial release (1965). I was a bit young to understand the history, but I totally understood that Omar Sharif was "dreamy." He was exotic and, therefore, fresh for American audiences. All the girls and women in the audience agreed with me, and there was solidarity among the men and boys concerning Julie Christie's beauty. Director David Lean, of course, was accepted as a powerhouse. The whole experience, as I recall, was enveloping and transporting. I knew nothing of the novel and was all caught up in Sharif's liquid brown eyes. I plan to revisit the film when we finish the book discussion and will, no doubt, see a very different film. The music haunted us for many months on the radio and in recordings. It is also important to remember that Lean's work was immense in scope and size; viewing it in even the largest home theater will never match the theatrical experience.

There is an aspect of "Dr. Zhivago" that is musical, symphonic. Interestingy, it echos a type of film popular in Europe in the 1920s -- City Symphonies -- for lack of a better term. Films such as Walter Ruttmann's "Berlin, Symphony of a City," Alberto Cavalcanti's "Rien que les heures," and Dziga Vertov's "Man with the Movie Camera," are good examples. Was Pasternak at all influenced by this film form? The ending of the book suggests that he may have at least been aware of it. In any case, I highly recommend watching Vertov's "Man with a Movie Camera" to get a feel for Soviet experimental film. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=op2sOt...

There is an aspect of "Dr. Zhivago" that is musical, symphonic. Interestingy, it echos a type of film popular in Europe in the 1920s -- City Symphonies -- for lack of a better term. Films such as Walter Ruttmann's "Berlin, Symphony of a City," Alberto Cavalcanti's "Rien que les heures," and Dziga Vertov's "Man with the Movie Camera," are good examples. Was Pasternak at all influenced by this film form? The ending of the book suggests that he may have at least been aware of it. In any case, I highly recommend watching Vertov's "Man with a Movie Camera" to get a feel for Soviet experimental film. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=op2sOt...

From en excellent review/analysis at:

From en excellent review/analysis at:http://booksandauthorsblog.com/archiv...

"Convinced that the Soviet state had betrayed the ideals of the revolution and that the drive for collectivism in Soviet society violated essential imperatives of human nature, sometime during the 1930s, Pasternak decided to turn from poetry to prose to tell the story of his generation and its historical fate under the tsar, during the Great War, and through the revolution and the establishment of the communist state, in part as an expression of survivor’s guilt. Writing in 1948, Pasternak admitted, 'I am guilty before everyone. But what can I do? So here in the novel—it is part of this debt, proof that at least I tried.' Drawing on his earlier interests in musical composition, philosophy, and a career devoted to poetry, Pasternak conceived a novel capacious enough to contain his 'views on art, the Gospels, human life in history and many other things.' Rejecting the 'idiotic clichés' of socialist realism and an edited, sanitized view of the revolution and its aftermath, Pasternak embraced the role as truth teller in which 'Everything is untangled, everything is named, simple, transparent, sad. Once again, afresh, in a new way, the most precious and important things, the earth and the sky, great warm feeling, the spirit of creation, life and death, have been delineated.'"

From an excellent review/analysis at: http://www.dspt.edu/dspt/lib/dspt/_sh...

From an excellent review/analysis at: http://www.dspt.edu/dspt/lib/dspt/_sh...The historical background to the novel is important, but only as it touches the inner lives of the characters. At one point the historical process, including revolution and war, starts to imitate nature.

“He reflected again that he conceived of history, of what is called the course of history, not in the accepted way but by analogy with the vegetable kingdom. In winter the leaf less branches under the snow are thin and poor... in spring the forest is transformed, it reaches the clouds, and you can hide or lose yourself in its leafy maze. ... And such to our eyes is the eternally growing, ceaselessly changing history...” (Ch. 14, §14).

We see Yurii and Lara in contrast to those whom the Revolution has transformed. Nikolai Nikolaevich Vedeniapin, Yurii’s uncle, is a Tol stoyan. He sees the Bolshevik revolution as the realization of the Tolstoyan messianic dream. We never hear what happens to him, but we see the identities of many of the intelligentsia swallowed up by the revolution: Pasha, young Vasya, even Yurii’s friends Misha and Innokentii Dudorov. The mystic Sima Tuntseva is also so caught up: she gives a long lecture to Lara on the mystical- religious transformation of Russia which the revolution has brought about, but the real transformation is to turn Sima into a fanatic."

In end, if "Dr. Zhivago" has left you drained and feeling hopeless, please consider Woody Allen's "Love and Death" (1975). You will cry, not from sadness, but because you are laughing so hard.

In end, if "Dr. Zhivago" has left you drained and feeling hopeless, please consider Woody Allen's "Love and Death" (1975). You will cry, not from sadness, but because you are laughing so hard. by

by

Woody Allen

Woody Allen

Joanne wrote: "In end, if "Dr. Zhivago" has left you drained and feeling hopeless, please consider Woody Allen's "Love and Death" (1975). You will cry, not from sadness, but because you are laughing so hard."

Joanne wrote: "In end, if "Dr. Zhivago" has left you drained and feeling hopeless, please consider Woody Allen's "Love and Death" (1975). You will cry, not from sadness, but because you are laughing so hard."Thanks, Joanne, it's ordered - I read up on it and it sounds just like my cuppa right now.

PASTERNAK & ZHIVAGO

PASTERNAK & ZHIVAGOThe Relationship Between Fiction and Fact

It has been cited that the character of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago may have been based in part on the real life Russian poet Alexandre Blok who was the most famous and influential of the Symbolist poets in turn of the century Russia. That Pasternak admired Blok is undoubted and that some aspects of Zhivago’s character were inspired by him is also very likely. Also, like Zhivago, Blok was the scion of a wealthy family, albeit St. Petersburg and not Moscow, but the resemblance ends there and takes up with another, now equally famous author of Pasternak’s acquaintance, Mikhail Bulgakov the author of The Master And Margarita.

Zhivago’s experiences as a doctor in the Tsarist Armies during the Great War and being conscripted as a medical officer during the Russian Civil War are pages that could have been taken directly from Bulgakov’s life. Bulgakov rarely spoke of his time as a medical officer as in neither instance did he serve with the forces that were to eventually rule Russia, a fact that could have served to mark him for extermination during the purges of the 1930s.

As to the relationship between Pasternak and Bulgakov here is a quote from Christopher Barnes’ Boris Pasternak A Literary Biography Volume 2 1928 – 1960 page 169:

"In early 1940 Pasternak also paid homage to another unappreciated literary celebrity. Along with many from the Arts Theatre he was grieved by news of Bulgakov’s terminal illness. He had visited him on his sickbed, although their long private conversation went unrecorded. Later, after Bulgakov’s death on 10 March, Pasternak was one of several actors, artists and writers in the guard of honour as his coffin stood in the Union of Writers."

The relationship between Pasternak and Bulgakov has never, to my knowledge, been cited as a possible inspiration for any aspects of Zhivago’s character. This may have been due to the fact that at the time of the publication and initial filmization of Zhivago, Bulgakov was virtually unknown outside the Soviet Union, his two major pieces, The Master And Margarita and The White Guard both having yet to be published in the West. (Note: The White Guard had an extremely limited publication in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and had been adapted by Bulgakov into the play The Days Of The Turbins, The Master And Margarita was not published anywhere in any format until the 1960s.)

In creating the character of Zhivago, Pasternak drew heavily from his own life and experiences while obviously incorporating some of the near mythological status that had been accorded Blok. That a share of the story that creates the richest portion of the dramatic structure of the book may have come from the life of Mikhail Bulgakov, a now legendary author in his own right is not only extremely interesting, but imperative to the understanding of the composition of one of the 20th Centuries greatest novels.

From - http://russianmemory.com/pasternak.htm

DR. ZHIVAGO AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

DR. ZHIVAGO AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONOpinions vary about whether the novel Dr. Zhivago is political or not. Some critics see it as apolitical ("Dr. Zhivago," Grolier's), whereas others, such as Bayley, who wrote the introduction to the present translation, sees it "first and foremost [as] a political novel, designed to express its author's overview of what is happening, and has happened, to his country and to her people" (vii). Political or not, the Russian Revolution is depicted accurately and in detail in Pasternak's novel Dr. Zhivago.

The events that lead to the 1917 revolution had started as early as in the 19th century. Lenin started his revolutionary activities in 1895. Bolsheviks and Mensheviks split in 1903, and on January 9, 1905, an estimated 1,000 workers were killed in Petersburg by Cossacks who fired on peaceful demonstrators. This event was called Bloody Sunday ("Russian revolution of 1905," Grolier's).

The events in Dr. Zhivago range from approximately 1905 to the 1940's, with most of the narrative concentrating on the revolution of 1917. At the beginning of the novel, Pasternak describes the revolutionary activities in Moscow from around 1905 to 1912. Working classes were marching along the streets carrying banners with revolutionary slogans, and singing "Warsaw" and "Victims they fell" (41). All kinds of people were participating in the demonstration.

Down the street people came pouring in a torrent - faces, faces, quilted winter coats and sheepskin hats, men and women students, old men, children, railway men in uniform, workers from the tramcar depot and the telephone exchange in knee boots and leather jerkins, girls and schoolboys. (41)

As in Petersburg on Bloody Sunday, Pasternak describes how the czar's troops cruelly killed the demonstrators:

"Then the sun, setting behind the houses, poked a finger round the corner and picked out everything that was red in the street - the red tops of the dragoons' caps, a red flag trailing on the ground and the red specks and threads of blood on the snow. (43)"

One of the main characters of the novel, Pasha Antipov, was active in the revolutionary movement. He distributed fliers and lead the marching band in demonstrations, without the slightest fear for his life. Dr. Zhivago himself, or Yuri, was at this time still a student at a medical institute. Yuri's attitude to the revolution was slightly more distant; he seemed to be sympathetic to the idea of revolution, but he kept out of the main action. Similarly, most of Yuri's acquaintances and relatives observed the course of events from the side without active participation.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Russian men were sent to the front. In Dr. Zhivago, Pasha Antipov enlisted in 1916 and was later sent to the Hungarian border. Yuri Zhivago, who was now working as a doctor, was stationed near the western border in a military hospital.

The outbreak of the war added to general discontent of people, which, in its turn, added more fuel to the upcoming 1917 revolution. Soldiers on the front were especially unhappy (Crankshaw 45). Pasternak describes the weary soldiers like this:

Tired young soldiers in enormous boots, their dusty tunics black with sweat on the chest and shoulder blades, sprawled, some on their backs, others face down, by the side of the road....They lay there as if they were made of stone, without energy to smile or swear. (112)

Czar Nicholas II was a weak leader and could not motivate the soldiers to fight, since the war was not going to benefit the soldiers in any way (Crankshaw 46). Yuri Zhivago met the czar when he visited the front to try to improve the morale of the soldiers, but he failed to make a good impression on Yuri.

The Tsar, smiling and ill at ease, looked older and more tired than his image on his coins and medals. His face was listless and a little flabby....Yuri felt sorry for the Tsar and horrified to think that this diffident reserve and shyness were the essential attributes of the oppressor, that such weakness could kill or pardon, bind or loose. (115)

Pasternak says that everything was being done to break the soldiers' apathy and tighten discipline (127). Not only the czar, but also his commissars were trying to restore order on the front. Since Bolsheviks were the ones against the czar, the commissars accused them of causing distraction on the front and in the nearby villages (132). Most people in the villages, however, did not seem to care for any doctrines; all they were interested in was peace and justice. As one outspoken woman, Ustinya, in the village said:

. . . that's all you talk about, bolsheviks and mensheviks. Now all that about no more fighting and all being brothers, I call that being godly, not menshevik, and about the works and factories going to the poor, that isn't bolshevik, that's according to the humanity and loving-kindness. (133)

The chronological events of World War I are followed closely in the novel. The Germans had broken through to the Russian territory and Yuri Zhivago had to move the military hospital to a different location (119). At the beginning of the year 1917, Russian soldiers were still on the front. In March they heard the news: "Street fighting in Petersburg! It's the Revolution!" (122) and later on, in the summer of 1917, the soldiers, among them Yuri Zhivago, were finally sent home.

The political events of the October 1917 were not described in great detail. Pasternak mentions that fighting increased in Moscow, and that the bolsheviks had earlier formed a provisional government (175). Yuri Zhivago read in the newspaper that the Dictatorship of Proletariat had been established (176).

In contrast to the relatively short description of the political events of the winter of 1917, more attention is given to the effect it had on the actual life of people. The winter was going to be hard. Yuri Zhivago and his family spent the winter of 1917 hungry and cold, "watching the destruction of all that was familiar and changing of all the foundations of life" (178). There was very little food and people had to eat whatever they could get hold of. The meals in the Zhivago household consisted of "boiled millet and fish soup made of herring heads, followed by the rest of the herring as the second course; there was also gruel made by boiling wheat or rye" (179).

During the following three years, Yuri Zhivago saw "an iron fist in everything" (178). Private property was seized, everything was guarded with guns, and "enterprise after enterprise became bolshevized" (178). Names of streets and government establishments were changed to better conform to the ideas of the revolution. For example, Governor-General Street was changed into October street (340), and the hospital where Zhivago worked in Moscow, Hospital of the Holy Cross, was turned into the Second Reformed Hospital (178).

In order to escape the hunger in the cities, a lot of people were going to the south or abroad (156). In addition, people who were afraid of the "iron fist" (178) decided that it was better to go to the countryside. In the novel, Yuri's half-brother Yevgraf, who was more active in the political arena, told Yuri that it was dangerous for him to stay in Moscow and that Yuri should take his family and go to the far-away city of Yuryatin in the Urals, where Yuri's late mother-in-law had owned a country estate called Varykino (189).

The October Revolution of 1917 led to the Civil War in 1918, battles between the Reds, the supporters of the new socialist government, and the Whites, who supported the pre-revolutionary state of affairs ("Russian revolutions of 1917," Grolier's). In Dr. Zhivago, the readers witness the devastating results of the Civil War: villages burnt by the Reds or Whites, cities occupied by first the Reds, then the Whites, and then the Reds again. For instance, when the Zhivago family were on their way to Yuryatin they saw villages burned by a revolutionary called Strelnikov, for not giving horses to the Red Army (206). The city of Yuryatin, where the Zhivagos were headed was rumored to be occupied by the white forces led by Yuri Zhivago's friend Galiullin (211).

Later on, the city of Yuryatin fell under the Red Army and the whole city underwent the same kinds of changes as were seen in Moscow. Various name changes occurred, and there were people's councils that abolished private ownership and controlled food distribution in the city. The huge Varykino estate, which was formerly private property of the Kruegers, the family of Yuri's mother-in-law, now became property of the Soviet state. The Zhivagos settled on the estate anyway, although Yuri admitted that their "use of land is illegal . . . The wood we cut is stolen, and it is no excuse that we steal from the State or that the property once belonged to Krueger" (252).

Later on, Yuri Zhivago was captured by the Red Army, who needed a medical officer. Yuri was forced to stay with them for almost two years. During this time, he witnessed a lot of unnecessary cruelty by the Red Army. For instance, once the Reds fought against a troop of white soldiers who turned out to be nothing but 14-year-old boys from a nearby military school. All the sympathies of Yuri Zhivago, who did not like human suffering of any kind, "were on the side of these heroic children who were meeting death. With all his heart he wished them success" (302).

During the time of the Civil War, many people who were not bolsheviks were deported from Russia. Yuri Zhivago's family, who had moved back to Moscow while Yuri was held by the Red Army, was deported to France, along with various other members of the intelligentsia, such as right-wing socialists, professors, and writers (373).

In 1921, the New Economic Policy, or NEP, was introduced, which restored some private property, and ended restrictions on private trade ("Russian Revolutions of 1917,"Grolier's). Yuri Zhivago arrived in Moscow again in 1922 at the beginning of NEP and saw that certain limited private enterprise was allowed at this time. He noticed, however, that such enterprise often "led to profiteering and speculation" (423). Yuri also noticed other changes in the city. Members of the gentry and intelligentsia who had stayed in the Soviet Union had become to accept the revolution and had modified their language accordingly. They now said "sure thing" instead of "very well" (423).

The years that followed the Civil War were relatively uneventful in Russia, with the exception of Stalin's terrors on individual people. ("Stalin," Grolier's). Yuri Zhivago lived a quiet life in Moscow until at least 1929. The fate of his former mistress, Lara, who was the wife of the revolutionary Strelnikov, was unknown during this time period. There was speculation, however that "she must have been arrested, as so often happened in those days. . . forgotten as a nameless number on a list which later was mislaid, in one of the innumerable mixed or women's concentrations camps in the north" (449).

In addition to painting a very accurate picture of the political events of the beginning of the century, the novel Dr. Zhivago looks into the lives and feelings of the aristocrats and intelligentsia living in Russia at that time (Slonim 225).

(continued next message)

http://flan.utsa.edu/russian/dr%20zhi...

DR. ZHIVAGO AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION (cont.)

DR. ZHIVAGO AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION (cont.) The aristocrats had led a wealthy and carefree life all the way up to the revolution. Yuri Zhivago grew up in Moscow in the household of his distant relatives, the Gromekos, who lived in a huge two-story house in the center of Moscow. On the second floor they had their living quarters, bedrooms, schoolroom, study, library, sitting room, Yuri's and Tonya's rooms. The ground floor was used for receptions (58). Most aristocrats, including the Gromekos, also had country estates. These were huge estates that were run by bailiffs and peasants as workers.

The Gromekos lived the life of cultivated, sophisticated aristocrats. They "loved music, held receptions and evenings of chamber music at which string quartets and piano trios were performed" (58). The aristocrats also gave a lot of lavish balls, with fine dresses, good food, drinking and dancing all night long (82).

The lavish life of the aristocrats came to and end with the revolution. They had to give up much of their private property, and share their housing with people of the lower classes (Hayward 103). The military hospital where Yuri Zhivago worked during World War I, had belonged to Countess Zhabrinskaya, who had given up her house to the Red Cross (126). Similarly, Yuri's mother-in-law's family estate had been confiscated by the Government. While Yuri was on the front, his wife, Tonya, had had to send all the servants away, except for one who was looking after the child (154). In addition, the Gromekos had given their downstairs away. Even the vocabulary for housing had changed. Rooms were not called "rooms" any more but "living space" (156). Yuri Zhivago, however, seemed to agree with the new arrangement.

". . . there really was something unhealthy in the way rich people used to live. Masses of superfluous things. Too much furniture, too much room, too much refinement, too much self-expression. I'm very glad we're using fewer rooms. We should give up still more." (156)

In the novel we can also see how the revolution which had seemed to promise such high hopes had developed under Stalin into a soulless tyranny (Introduction to Dr. Zhivagovi). Yuri Zhivago, like many students of the time, had eagerly supported the 1905 revolution and the idealism behind it. Now, with the bolsheviks in charge, he was less pleased with it.

These new things were not familiar, not led up to by the old. . . Such a new thing, too, was this revolution, not the one idealised in the student fashion in 1905, but this new upheaval, today's born of the war, bloody, pitiless, elemental, the soldiers' revolution, led by the professionals, the bolsheviks. (148)

Yuri seemed to be much more moderate in his ideas of the revolution. On the train back to Moscow from the front he met a true revolutionary, who believed in a bloody revolution, a total disintegration of the current society, so that the whole system can be started from scratch. Yuri Zhivago was horrified at his words (151). Yuri also understood that his fate was sealed. He was convinced he was doomed, because he was not believed to be "red enough". He was also very disenchanted with the way things had turned out (168), and for the rest of his life Yuri felt isolated from the society and he never was able to fully adjust to the Soviet system.

In conclusion, in the novel Dr. Zhivago, the readers can see all the main events of the Russian revolution through the eyes of aristocrats. It is an accurate and truthful picture, although it did not turn out to be the kind of truth the Soviet government wanted. Nevertheless, it was an honest and accurate depiction of reality.

WORKS CITED

Crankshaw, Edward. The Shadow of the Winter Palace. London: MacMillan, 1976.

"Dr. Zhivago." The 1996 Grolier's Multimedia Encyclopedia, vers. 8.0.3 CD-ROM. Danbury, CT: Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1996.

Hayward, Max. Writers in Russia: 1917-1978. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Pasternak, Boris. Dr. Zhivago. New York: Alfred Knopf, Inc., 1991.

"Pasternak, Boris." The 1996 Grolier's Multimedia Encyclopedia, vers. 8.0.3 CD-ROM. Danbury, CT: Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1996.

"Russian Revolution of the 1905." The 1996 Grolier's Multimedia Encyclopedia, vers. 8.0.3 CD-ROM. Danbury, CT: Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1996.

"Russian Revolutions of 1917." The 1996 Grolier's Multimedia Encyclopedia, vers. 8.0.3 CD-ROM. Danbury, CT: Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1996.

Slonim, Marc. Soviet Russian Literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

"Stalin." The 1996 Grolier's Multimedia Encyclopedia, vers. 8.0.3 CD-ROM. Danbury, CT: Grolier Electronic Publishing, 1996.

http://flan.utsa.edu/russian/dr%20zhi...

From the Nobel site: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prize...

From the Nobel site: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prize..."The Nobel Prize in Literature 1958 was awarded to Boris Pasternak 'for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition'."

And - the poems of Pasternak - (about 122 - there are only 25 in the book)

The poems on this page are listed in alphabetical order -

http://www.poemhunter.com/boris-paste...

This is more on the Christina mentioned in Chapter 16 - there's a bit above but this is more thorough -

This is more on the Christina mentioned in Chapter 16 - there's a bit above but this is more thorough - From http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-r...

Zoya Anatolyevna Kosmodemyanskaya was a guerilla fighter and a member of a Red Army Western Front sabotage and reconnaissance force. She was the first woman awarded with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union during World War II. She became the symbol of the Soviet people’s heroism in protecting their motherland. Her image is depicted in fiction, essays, movies and art.

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was born in a village in the central Russian Tambov Region into a family of local priests. When she was six, her family found themselves in Siberia. Some research suggests they were expelled for Zoya’s father’s speech against collective farming, but in a report published in 1986, her mother stated that they had run to Siberia to escape an accusation. For a year, they lived on the Biryusa River in Southeastern Siberia, but later moved to Moscow. Zoya’s father died when Zoya was ten, after intestinal surgery, and the children, Zoya and her younger brother Aleksandr, remained under their mother’s care.

Zoya did well in school, was especially fond of history and literature and dreamed of entering Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) University. However, her relationships with her classmates did not develop well, and that, according to her mother, led to a “nerve illness.” Some witnesses suggested she had schizophrenia. In 1940 she was ill with acute meningitis, after which she underwent rehabilitation in Moscow’s Sokolniki clinic, where she befriended writer Arkady Gaydar, who was also there for treatment. Despite having missed many classes, she graduated from nine-grade secondary school later that same year.

On 31 October 1941, Zoya, together with 2,000 young communist volunteers entered a sabotage school, becoming a member of a sabotage and reconnaissance force officially named the “guerilla troop of the 9903rd staff of the Western Front.” After a short period of training, she was sent to the Volokolamsk District of the Moscow Region where she and her group succeeded in laying mines on a road. Later, Stalin issued an order to prevent the German army from stationing in towns and villages, and thus to burn and destroy all settlements in the German rear. To fulfill the order, sabotage group commanders were to burn ten settlements within a week, including the village of Petrishevo in the western Moscow Region. Two groups set out on the mission, but came under German fire and, after taking heavy casualties, scattered. Their remnants then rejoined under the command of Boris Kraynev.

On 27 November Kraynev, Vasily Klubkov and Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya set fire to three houses in Petrishchevo, where German soldiers and officers were stationed. Then, as they scattered to rendezvous at a prearranged meeting point, Kraynev left without waiting for his comrades. Klubkov was captured by the Nazis, and Zoya, left alone, decided to return to Petrishchevo and continue burning the village. However, both the Germans and the locals were already on alert, and the Germans had positioned several local men to guard the village against saboteurs. At nightfall the next day, Zoya was spotted by one of the guards as she tried to set fire to a barn. The guard called the Germans, who captured Zoya. The Nazis rewarded the local man with a bottle of vodka, and later, a Soviet court sentenced him to death.

At the interrogation, Zoya said her name was Tanya and refused to say anything definite. The Germans stripped her naked and lashed her, then marched her outside in the freezing cold. Local women also tried to take part in the humiliation, by throwing a pot full of dishwater at her. Later, they too were sentenced to death. The next morning, Zoya was hanged with a tablet saying “arsonist” on her chest. Her body remained hung up for another month, and suffered numerous more humiliations from passing German soldiers. Then the Germans ordered the removal of the gallows, and Zoya’s body was buried outside the village, and later, reburied at the Novodevichye Cemetery in Moscow.

Zoya’s fate became widely known after the publicaton of Petr Lidov’s article “Tanya” in the Pravda newspaper in January 1942. The author learned of the Petrishchevo execution by chance, from a local elderly peasant who had witnessed it. In February the same year Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

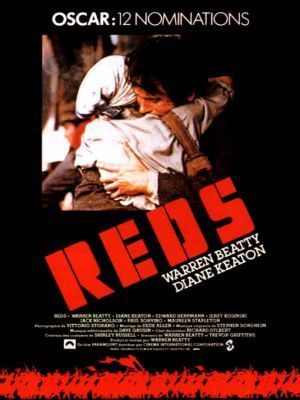

"Reds" (1981) was very well received at the time of its release and I'm looking forward to revisiting it, having recently finished "Doctor Zhivago."

"Reds" (1981) was very well received at the time of its release and I'm looking forward to revisiting it, having recently finished "Doctor Zhivago."

Becky wrote: " Leon Trotsky

Becky wrote: " Leon TrotskyIt has been suggested that Leon Trotsky was a very loose "model" for Strelnikov. There are similarities:

From: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

Leon Trot..."

Trotsky's grandson remembers his grandfather's murder and death in Mexico City, 72 years ago, today.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/...

Interesting! Yes, Trotsky was one of those who was deported and landed in France (like some in Pasternak's novel although he would not have been associated with them). Later he was forcibly moved to Mexico where he was assassinated at the home of Diego Rivera.

Interesting! Yes, Trotsky was one of those who was deported and landed in France (like some in Pasternak's novel although he would not have been associated with them). Later he was forcibly moved to Mexico where he was assassinated at the home of Diego Rivera. Barbara Kingsolver's book, The Lacuña, is partly about Trotsky's time there and it feels like she's got the history right. Checking that was the most interesting part of the book for me.

Barbara Kingsolver

Barbara Kingsolver

Books mentioned in this topic

The Lacuna (other topics)The Complete Prose (other topics)

To the Finland Station (other topics)

To the Finland Station (other topics)

Pasternak's "Dr. Zhivago": A Critical Companion (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Barbara Kingsolver (other topics)Woody Allen (other topics)

Edmund Wilson (other topics)

Edmund Wilson (other topics)

Edith W. Clowes (other topics)

More...

http://www.thegreatcourses.com/tgc/co...

Prof. Stienberg is also the author of several books, including "Petersburg Fin de Siecle."