The History Book Club discussion

ART - ARCHITECTURE - CULTURE

>

ARCHITECTURE

Gothic Architecture - English Perpendicular Gothic (c. 1350– c.1550)

Gothic Architecture - English Perpendicular Gothic (c. 1350– c.1550)

Manchester Cathedral

Overview:

The perpendicular Gothic period (or simply Perpendicular) is the third historical division of English Gothic architecture, and is so-called because it is characterised by an emphasis on vertical lines. An alternative name, the Rectilinear, was suggested by Edmund Sharpe, and is preferred by some as more accurate, but has never gained widespread use.

The Perpendicular style began to emerge c. 1350. Harvey (1978) puts the earliest example of a fully formed Perpendicular style at the chapter house of Old St Paul's Cathedral, built by William Ramsey in 1332. It developed from the Decorated style of the late 13th century and early 14th century, and lasted into the mid 16th century. It began under the royal architects William Ramsey and John Sponlee, and fully developed in the prolific works of Henry Yevele and William Wynford.

In the later examples of the Decorated Period the omission of the circles in the tracery of windows had led to the employment of curves of double curvature which developed into flamboyant tracery: the introduction of the perpendicular lines was a reaction in the contrary direction. The style grew out of the shadow of the Black Death which killed about half of England's population in 18 months between June 1348 and December 1349 and returned in 1361–62 to kill another fifth. This had a great effect on the arts and culture, which took a decidedly morbid and pessimistic direction. It can be argued that Perpendicular architecture reveals a populace affected by overwhelming shock and grief, focusing on death and despair, and no longer able to justify previous flamboyance or jubilation present in the Decorated style. The style was affected by the labour shortages caused by the plague as architects designed less elaborately to cope.

Features

This perpendicular linearity is particularly obvious in the design of windows, which became very large, sometimes of immense size, with slimmer stone mullions than in earlier periods, allowing greater scope for stained glass craftsmen. The mullions of the windows are carried vertically up into the arch moulding of the windows, and the upper portion is subdivided by additional mullions (supermullions) and transoms, forming rectangular compartments, known as panel tracery. Buttresses and wall surfaces are likewise divided up into vertical panels. The technological development and artistic elaboration of the vault reached its pinnacle, producing intricate multipartite lierne vaults and culminating in the fan vault.

Doorways are frequently enclosed within a square head over the arch mouldings, the spandrels being filled with quatrefoils or tracery. Pointed arches were still used throughout the period, but ogee and four-centred Tudor arches were also introduced.

Inside the church the triforium disappears, or its place is filled with panelling, and greater importance is given to the clerestory windows, which are often the finest features in the churches of this period. The mouldings are flatter than those of the earlier periods, and one of the chief characteristics is the introduction of large elliptical hollows.

Some of the finest features of this period are the magnificent timber roofs; hammerbeam roofs, such as those of Westminster Hall (1395), Christ Church Hall, Oxford, and Crosby Hall, appeared for the first time. In areas of Southern England using flint architecture, elaborate flushwork decoration in flint and ashlar was used, especially in the wool churches of East Anglia.

Notable examples

Some of the earliest examples of the Perpendicular Period, dating from 1360, are found at Gloucester Cathedral, where the masons of the cathedral seemed to be far in advance of those in other towns; the fan-vaulting in the cloisters is particularly fine. Perpendicular additions and repairs can be found in smaller churches and chapels throughout England, of a common level of technical ability which lack the decoration of earlier stonemasonry at their sites, so can be used for school field trips seeking evidence of the social effects of the plagues.

Among other buildings and their noted elements are:

nave, western transepts and crossing tower of Canterbury Cathedral (1378–1411),

late 15th-century tower, New College, Oxford (1380–86, Henry Yevele);

Beauchamp Chapel, Warwick (1381–91);

Quire and tower of York Minster (1389–1407);

remodelling of the nave and aisles of Winchester Cathedral (1399–1419);

transept and tower of Merton College, Oxford (1424–50);

Manchester Cathedral (1422);

Divinity School, Oxford (1427–83);

King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446–1515) [1]

Eton College Chapel, Eton (1448–1482) [2]

central tower of Gloucester Cathedral (1454–57);

central tower of Magdalen College, Oxford (1475–80);

choir of Sherborne Abbey (1475–c. 1580)

Collegiate Church Of The Holy Trinity, Tattershall, Lincolnshire. (c1490 - 1500) [3]

Notable later examples include Bath Abbey (c. 1501 – c. 1537, although heavily restored in the 1860s), Henry VII's Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503–1519), and the towers at St Giles' Church, Wrexham and St Mary Magdalene, Taunton (1503–1508).

The Perpendicular style was less often used in the Gothic Revival than the Decorated style, but major examples include the rebuilt Palace of Westminster (i.e. the Houses of Parliament), Bristol University's Wills Memorial Building (1915–25), and St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney.

Example of the English Perpendicular Ghotic:

Eton College Chapel

Source: Wikipedia

Gothic architecture - Rayonnant Gothic 1240-c. 1350 (France, Germany, Central Europe)

Gothic architecture - Rayonnant Gothic 1240-c. 1350 (France, Germany, Central Europe)Overview:

In French Gothic architecture, Rayonnant was the period between c. 1240 and 1350, characterized by a shift in focus away from the High Gothic mode of utilizing great scale and spatial rationalism (such as with buildings like Chartres Cathedral or the nave of Amiens Cathedral) towards a greater concern for two dimensional surfaces and the repetition of decorative motifs at different scales.

Whilst all phases of Gothic architecture were concerned to some degree with levels of illumination and the appearance of structural lightness, Rayonnant takes this to the extreme. More of the wall surface than ever before was pierced by windows (for example the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris) and buildings were often given lace-like tracery screens on the exterior to hide the bulk of load bearing wall elements and buttresses (such as at Strasbourg Cathedral or the Church of St Urbain in Troyes).

Example: Cologne Cathedral

The high choir of Cologne Cathedral (1248–1322) is considered as one of the finest Rayonnant structures of the Middle Ages.

Source: Wikipdia

Gothic architecture - Venetian Gothic 14th - 15th centuries (Venice in Italy)

Gothic architecture - Venetian Gothic 14th - 15th centuries (Venice in Italy)

Doge's Palace

Overview:

Venetian Gothic is a term given to an architectural style combining use of the Gothic lancet arch with Byzantine and Moorish architecture influences. The style originated in 14th century Venice with the confluence of Byzantine styles from Constantinople, Arab influences from Moorish Spain and early Gothic forms from mainland Italy. Chief examples of the style are the Doge's Palace and the Ca'd'Oro in Venice.

In the 19th Century, the works of John Ruskin and others drew from the style in a revival, part of the broader Gothic Revival movement in Victorian architecture.

Characteristics and examples:

Unique to the Venetian Gothic architectural style is the desire for lightness and grace in structure. While other European cities often favored heavy buildings, Venice had always held the concern that every inch of land is valuable, because of the canals running through the city. Therefore, the Venetian Gothic, while far more intricate in style and design than previous construction types in Venice, never allowed more weight or size than necessary to support the building. This is an interesting concept because, while the window traceries in Northern Gothic construction only supported stained glass, the traceries in Venetian Gothic supported the weight of the entire building. Therefore the immense weight sustained by the traceries only alludes to the extreme weightlessness of the buildings as a whole.

One major aspect of the Venetian Gothic style change that came about during the 14th and 15th centuries was the proportion of the central hall in secular buildings. This hall, known as the portego, evolved into a long passageway that was often opened by a loggia with gothic arches. Architects favored using intricate traceries, similar to those found on the Doge’s Palace.

The most iconic Venetian Gothic structure, the Doge's Palace, is a luxuriously decorated building that includes traits of Gothic, Moorish, and Renaissance architectural styles. In the 14th Century, following two fires that destroyed the previous structure, the palace was rebuilt in its present, recognizably Gothic form.

Yet another important example of Venetian Gothic architecture is Santa Maria dei Frari, a Franciscan church. First constructed in the 1400s, this Franciscan church was rebuilt in its current Gothic style in the 15th Century.

Examle: Palazzo Cavalli-Franchetti

Source: Wikipedia

Please correct me if I'm wrong but aren't some of the ancient buildings in Venice slowly falling to ruin because of the canals and the water eating away at the foundation?

Please correct me if I'm wrong but aren't some of the ancient buildings in Venice slowly falling to ruin because of the canals and the water eating away at the foundation?

You are not wrong but the buildings are not falling to ruin, the whole city is sinking, faster each year, because the foundations are built of wood. Did you know that the wood used for the foundations the Venetians took from the Croatian mountain Velebit. The stories say that Velebit was one full of beautiful woods but that Venetians took down so much of it, it's now all naked.

You are not wrong but the buildings are not falling to ruin, the whole city is sinking, faster each year, because the foundations are built of wood. Did you know that the wood used for the foundations the Venetians took from the Croatian mountain Velebit. The stories say that Velebit was one full of beautiful woods but that Venetians took down so much of it, it's now all naked.

When I was in Venice last year, on one of the canals I actually saw a level of one house bellow water. If I remember correctly, I saw the door.

When I was in Venice last year, on one of the canals I actually saw a level of one house bellow water. If I remember correctly, I saw the door.

I never got to Venice when I was in Italy but had heard that the water was causing severe problems. I wonder how they are addressing it. It would be criminal to lose some of those historic homes/buildings. Interesting and sad information about the wood from Croatia. Thanks, Samanta

I never got to Venice when I was in Italy but had heard that the water was causing severe problems. I wonder how they are addressing it. It would be criminal to lose some of those historic homes/buildings. Interesting and sad information about the wood from Croatia. Thanks, Samanta

That info I do not have but it would be interesting to do some research. I do know they are trying to limit the number of tourists that enter but that's only a surface solution.

That info I do not have but it would be interesting to do some research. I do know they are trying to limit the number of tourists that enter but that's only a surface solution.

I wouldn't have a clue as to what they could do except drain the canals and of course that is not an option. It is a precarious situation.

I wouldn't have a clue as to what they could do except drain the canals and of course that is not an option. It is a precarious situation.

Terrific.....be sure and post what you find. It is an interesting topic that we never think of much and yet, it could destroy some classic architecture.

Terrific.....be sure and post what you find. It is an interesting topic that we never think of much and yet, it could destroy some classic architecture.

Jill, here is an article on sattelite measuring of the sinking of Venice:

Jill, here is an article on sattelite measuring of the sinking of Venice:Venice's Gradual Sinking Charted by Satellites

By Tanya Lewis

Maps of the displacement rate (mm/yr) detected at Venice by TerraSAR-X satellites from March 2008 and January 2009. Negative values indicate settlement, positive mean uplift.

The results revealed the city is naturally subsiding at a rate of about 0.03 to 0.04 inches (0.8 to 1 millimeter) per year, while human activities contribute sinking of about 0.08 to 0.39 inches (2 to 10 mm) per year. However, human activities, such as conservation and reconstruction of buildings, cause sinking only on a localized, short-term scale, the researchers said.

The sinking threatens to increase flooding in Venice, which already occurs due to high tides about four times per year. And the problems are compounded by rising sea levels resulting from climate change. The Northern Adriatic Sea is rising at about 0.04 inches (1 mm) per year, Teatini said. To buffer this rise, the MOSE (Experimental Electromechanical Module) project, planned to begin in 2016, will install a system of movable gates that would block the inlets to the Venetian lagoon during high tides.

Read more here: Venice's Gradual Sinking Charted by Satellites

Source: livescience.com

Also one of the studies conducted on the subject:

Also one of the studies conducted on the subject:Injections Could Lift Venice 12 Inches, Study Suggests

By Brian Handwerk, for National Geographic News

Piazza San Marco under water

Injecting billions of gallons of seawater could "inflate" porous sediments under the canal-crossed city, causing the Italian city to rise by as much as a foot (about 30 centimeters), scientists say.

Under the plan, a dozen wells surrounding Venice in a six-mile (ten-kilometer) circle would pump water into the ground over a ten-year period—nearly 40 billion gallons in all (150 billion liters).

Read more on: Injections Could Lift Venice 12 Inches, Study Suggests

Source: National Geographic

Yeah, it is! Imagine living right across it, one the same sea, but not having those kind of problems.

Yeah, it is! Imagine living right across it, one the same sea, but not having those kind of problems.

Thanks so much, Samanta. It is a terrible problem and I hope they follow through with their plans. Look at that picture of the Piazza San Marco!!!!.......the damage being done to those old buildings is heartbreaking.

Thanks so much, Samanta. It is a terrible problem and I hope they follow through with their plans. Look at that picture of the Piazza San Marco!!!!.......the damage being done to those old buildings is heartbreaking.The movable gates seems like only a partial fix though....it will stop the tide flooding but since Venice is sitting on porous ground, I would think that it would continue to sink, just not as fast. Not being an engineer, what do I know but they have some tough challenges ahead.

The "funny" thing is that the citizens are already so used to it that they only consider it a nuisance, a not a big problem.

The "funny" thing is that the citizens are already so used to it that they only consider it a nuisance, a not a big problem.

I would think it would be more than a nuisance if my front door was underwater!!!!! Oh well, just keep diving equipment in your front room.

I would think it would be more than a nuisance if my front door was underwater!!!!! Oh well, just keep diving equipment in your front room.

Gothic architecture - Spanish Gothic - late Medieval period

Gothic architecture - Spanish Gothic - late Medieval periodSpanish Gothic architecture is the style of architecture prevalent in Spain in the Late Medieval period.

The Gothic style started in Spain as a result of Central European influence in the twelfth century when late Romanesque alternated with few expressions of pure Gothic architecture. The High Gothic arrives with all its strength via the pilgrimage route, the Way of Saint James, in the thirteenth century. Some of the most pure Gothic cathedrals in Spain, closest related to the German and French Gothic, were built at this time.

The Gothic style was sometimes adopted by the Mudéjar architects, who created a hybrid style, employing European techniques and Spanish-Arab decorations. The most important post−thirteenth-century Gothic styles in Spain are the Levantino, characterized by its structural achievements and the unification of space, and the Isabelline Gothic, under the Catholic Monarchs, that predicated a slow transition to Renaissance style architecture.

Sequence of Gothic styles in Spain:

The designations of styles in Spanish Gothic architecture are as follows. Dates are approximate.

Early Gothic (twelfth century)

High Gothic (thirteenth century)

Mudéjar Gothic (from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries)

Levantino Gothic (fourteenth century)

Flamboyant/Late Gothic (fifteenth century)

Isabelline Gothic (fifteenth century)

Example: León Cathedral

Source: Wikipedia

Indeed! Gothic architecture is something special. I am at the moment in Luxembourg for vacations. I went to Metz, France for a visit. The cathedral over there took my breath away. It's enormous.

Indeed! Gothic architecture is something special. I am at the moment in Luxembourg for vacations. I went to Metz, France for a visit. The cathedral over there took my breath away. It's enormous.

Gothic Architecture - Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon (c.1200-1700)

Gothic Architecture - Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon (c.1200-1700)

La Mota castle. Medina del Campo, Valladolid

Overview:

Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon is an aesthetic trend in the Mudéjar style, which is centered in Aragon (Spain) and has been recognized in some representative buildings as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The chronology of the Aragonese Mudejar occupies 12th to the 17th century and includes more than a hundred architectural monuments located predominantly in the valleys of the Ebro, Jalón and Jiloca. In this area there was a large population of Muslim origin, although many of them were nominally Christian. Described as Mudejar or Morisco, they kept their workshops and craft traditions, and rarely used stone as building material.

The first manifestations of Aragonese Mudejar have two origins: on the one hand, a palatial architecture linked to the monarchy, which amends and extends the Aljafería Palace maintaining Islamic ornamental tradition, and on the other hand, a tradition which develops Romanesque architecture using brickwork rather than masonry construction and which often displays Hispanic-rooted ornamental tracery. Examples of the latter type of mudejar architecture can be seen in churches in Daroca, which were started in stone and finished off in the 13th century with Mudejar brick panels.

From the construction point of view, the Mudejar architecture in Aragon preferably adopts functional schemes of Cistercian Gothic, but with some differences. Buttresses are often absent, especially in the apses which characteristically have an octagonal plan with thick walls that can hold the thrust from the roof and which provide space to highlight brick decorations. On the other hand, buttresses are often a feature of the naves, where they may be topped by turrets, as in the style of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar. There may be side chapels which are not obvious from the exterior. Churches in neighborhoods (such as San Pablo of Zaragoza) or small towns do not usually have aisles, but locations for additional altars are provided by chapels between the nave buttresses. It is common for these side chapels to have a closed gallery or ándite (walkway), with windows looking to the outside and inside of the building. This constitution is called a church-fortress, and his prototype could be the church of Montalbán.

Typically the bell towers show extraordinary ornamental development, the structure is inherited from the Islamic minaret: quadrangular with central pier whose spaces are filled via a staircase approximation vaults, as in the Almohad minarets. On this body stood the tower, usually polygonal. There are also examples of octagonal towers.

Aljafería Palace in Zaragoza, Aragon

Sources: Wikipedia and Spainisculture

Gothic architecture - Isabelline Gothic 1474-1505 (reign) (Spain)

Gothic architecture - Isabelline Gothic 1474-1505 (reign) (Spain)

Miraflores Charterhouse, Burgos

Overview:

Isabelline Gothic (in Spanish, Gótico Isabelino), was the dominant architectural style of the Crown of Castile during the reign of Queen Isabella I; it represents the transition between late Gothic and early Renaissance architecture, with original features and decorative influences of Mudéjar, Flemish, and to a lesser extent, Italian architecture.

The Isabelline style introduced several structural elements of the Castilian tradition and the typical Flemish Flamboyant forms, as well as some ornaments of Islamic influence. Many of the buildings that were built in this style were commissioned by the Catholic Monarchs or were in some way sponsored by them. A similar style called Manueline developed concurrently in Portugal. The most obvious characteristic of the Isabelline is the predominance of heraldic and epigraphic motifs, especially the symbols of the yoke and arrows and the pomegranate, which refer to the Catholic Monarchs. Also characteristic of this period is ornamentation using beaded motifs of orbs worked in plaster or carved in stone.

After the Catholic Monarchs had completed the Reconquista in 1492 and started the colonization of the Americas, imperial Spain began to develop a consciousness of its growing power and wealth, and in its exuberance launched a period of construction of grand monuments to symbolize them. Many of these monuments were built at the command of the Queen; thus Isabelline Gothic manifested the desire of the Spanish ruling classes to display their own power and wealth. This exuberance found a parallel expression in the extreme profusion of decoration which has been called Plateresque.

References to classical antiquity in the architecture of Spain were more literary, whereas in Italy, the prevalence of Roman-era buildings had given 'Gothic' a meaning adapted to Italian classicist taste. Until the Renaissance took hold in the Iberian peninsula, the transition from the 'Modern' to the 'Roman' in Spanish architecture had hardly begun. These terms were applied with a meaning different from what one would expect now—the 'Modern' referred to the Gothic and the Platereque decorative vocabulary,[1] while the 'Roman' was the neoclassical or purist style of the Italian Renaissance.

Regardless of the spatial characteristics of the interiors, Gothic buildings utilized proven structural systems. The Gothic style in the Iberian Peninsula had undergone a series of changes under the influence of local tradition, including much smaller windows which allowed the construction of roofs with substantially less pitch and even flat roofs. This made for a truly original style, yet more efficient construction. Spanish architects, accustomed to their Gothic structural conventions, looked with some contempt on the visible metal braces that Italian architects were forced to put on their buildings' arches to resist horizontal thrust, while their own Gothic building methods had avoided this problem.

The development of classical architecture in the Iberian Peninsula, as elsewhere, had been moribund during the centuries of building construction done in the Gothic tradition, and the neoclassical movement of the Italian Renaissance was late to arrive there. A unique style with modern elements evolved from the Gothic inheritance. Perhaps the best example of this syncretistic style is the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo; designed by the architect Juan Guas; its Gothic ideals are expressed more in the construction than in the design of the interior space, as the relationship with original French Gothic building techniques had receded with the passage of time.

In the Isabelline style, decorative elements of Italianate origin were combined with Iberian traditional elements to form ornamental complexes that overlay the structures, while retaining many Gothic elements, such as pinnacles and pointed arches. Isabelline architects clung to the Gothic solution of the problem of how to distribute the weight burden of vaults pressing on pillars (not on the walls, as in the Romanesque or Italian Renaissance styles): that is, by propping them up with flying buttresses. After 1530, although the Isabelline style continued to be used and its decorative ornaments were still evolving, Spanish architecture began to incorporate Renaissance ideas of form and structure.

Iglesia de San Jeronimo el Real, Madrid (St. Jerome Royal Church)

Source: Wikipedia

Gothic architecture - Plateresque 1490-1560 (Spain & colonies, bridging Gothic and Renaissance styles)

Gothic architecture - Plateresque 1490-1560 (Spain & colonies, bridging Gothic and Renaissance styles)

Facade of the University of Salamanca, Spain

Plateresque, meaning "in the manner of a silversmith" (Plata means silver in Spanish), was an artistic movement, especially architectural, traditionally held to be exclusive to Spain and its territories, which appeared between the late Gothic and early Renaissance in the late 15th century, and spread over the next two centuries. It is a modification of Gothic spatial concepts and an eclectic blend of Mudéjar, Flamboyant Gothic and Lombard decorative components, and Renaissance elements of Tuscan origin. Examples of this syncretism are the inclusion of shields and pinnacles on facades, columns built in the Renaissance neoclassical manner, and facades divided into three parts (in Renaissance architecture they are divided into two).

It reached its peak during the reign of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, especially in Salamanca, but also flourished in other cities of the Iberian Peninsula as León and Burgos and in the territory of New Spain, which is now Mexico. Plateresque has been considered down to current times a Renaissance style by many scholars. To others, it is its own style, and sometimes receives the designation of Protorenaissance. Some even call it First Renaissance in a refusal to consider it as a style in itself, but to distinguish it from non-Spanish Renaissance works.

The style is characterized by ornate decorative facades covered with floral designs, chandeliers, festoons, fantastic creatures and all sorts of configurations. The spatial arrangement, however, is more clearly Gothic-inspired. This fixation on specific parts and their spacing, without structural changes of the Gothic pattern, causes it to be often classified as simply a variation of Renaissance style. In New Spain the Plateresque acquired its own configuration, clinging tightly to its Mudéjar heritage and blending with Native American influences. A Plateresque style could also be said to have developed in the first decades of the 16th century in southern France and Portugal.

In the 19th century with the rise of historicism, the Plateresque architectural style was revived under the name of Monterrey Style.

Facade of the New Cathedral of Salamanca, Spain

Features

Spanish Plateresque

Typical Plateresque facades, like those of altarpieces, were made as carefully as if they were the works of goldsmiths, and decorated as profusely. The decoration, although of various inspirations, was mainly of plant motifs, but also had a profusion of medallions, heraldic devices and animal figures, among others. Plateresque utilized a wealth of materials: gold plates on crests and roofs, vases, etc. There is evidence of more polychrome works at the conclusion of the first third of the 16th century, when there appeared heraldic crests of historical provenance and long balustrades, to mention one kind of less busy decoration.

The proliferation of decoration for all architectural surfaces led to the creation of new surfaces and subspaces, which were in turn decorated profusely, such as niches and aediculas.

Italian elements were also being developed progressively as decoration: rustications, classical capitals, Roman arches and especially grotesques.

The decoration had specific meanings and can not be read as merely decorative; thus laurels, military shields and horns-of-plenty were placed in the houses of military personnel. In a similar vein, Greek and Roman myths were depicted elsewhere to represent abstract humanist ideals, so that the decorative became a means to express and disseminate Renaissance ideals.

Plataresque implemented and preferred new spatial aspects, so caustrales, or stairs of open boxes, made their appearance.[12] However, there were few spatial changes with respect to the Gothic tradition.

American Plateresque

In America, especially in today's Mexico, various indigenous cultures were in certain stages of development that can be considered Baroque when the Spanish brought with them the Plateresque style. This European phenomenon mixed symbiotically with local traditions, so that pure Gothic architecture was not built in America itself, but the Plateresque mixed with Native American influences, soon evolving into what came to be called American Baroque.

Plateresque Gothic (late 15th century–1530)

The movement began in late 15th century Spain to disguise Gothic buildings with florid decoration, especially grotesques, but the superficial application of this principle did not change the spatial qualities or architectural structure of those buildings. This process began when the Renaissance arrived in Spain and architects began copying Renaissance architectural features without understanding the new ideas behind them, that is, without letting go of medieval forms and ideas.

Many of the Plateresque buildings were already built, to which were added only layers of Renaissance ornamentation, especially around openings (windows and doors), and in general, all non-architectural elements, with some exceptions.

Although the appellation 'Plateresque' is usually applied to the act of superimposing new Renaissance elements on forms governed by medieval guidelines in architecture, this trend is also seen in the Spanish painting and sculpture of the time.

The Facade of Convento de San Esteban, Salamanca, Spain

Source: Wikipedia

I've never been to Salamanca, only Madrid and Barcelona but when I get a chance to go again I'm definitely making my own itinerary. What did you visit?

I've never been to Salamanca, only Madrid and Barcelona but when I get a chance to go again I'm definitely making my own itinerary. What did you visit?

Gothic architecture - Flamboyant Gothic 1400-1500 (Spain, France, Portugal)

Gothic architecture - Flamboyant Gothic 1400-1500 (Spain, France, Portugal)

The main facade of the Parliament of Normandy, Rouen, France

Overview:

Flamboyant (from French flamboyant, "flaming") is the name given to a florid style of late Gothic architecture in vogue in France from about 1350 until it was superseded by Renaissance architecture during the early 16th century, and mainly used in describing French buildings. The term is sometimes used of the early period of English Gothic architecture usually called the Decorated Style; the historian Edward Augustus Freeman proposed this in a work of 1851. A version of the style spread to Spain and Portugal during the 15th century. It evolved from the Rayonnant style and the English Decorated Style and was marked by even greater attention to decoration and the use of double curved tracery. The term was first used by Eustache-Hyacinthe Langlois (1777–1837), and like all the terms mentioned in this paragraph except "Sondergotik" describes the style of window tracery, which is much the easiest way of distinguishing within the overall Gothic period, but ignores other aspects of style. In England the later part of the period is known as Perpendicular architecture. In Germany Sondergotik ("Special Gothic") is the more usual term.

The name derives from the flame-like windings of its tracery and the dramatic lengthening of gables and the tops of arches. A key feature is the ogee arch, originating in Beverley Minster, England around 1320, which spread to York and Durham, although the form was never widely used in England, being superseded by the rise of the Perpendicular style around 1350. A possible point of connection between the early English work and the later development in France is the church at Chaumont. The Manueline in Portugal, and the Isabelline in Spain were even more extravagant continuations of the style in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

In the past the Flamboyant style, along with its antecedent Rayonnant, has frequently been disparaged by critics. More recently some have sought to rehabilitate it. William W Clark commented:

The Flamboyant is the most neglected period of Gothic architecture because of the prejudices of past generations; but the neglect of these highly original and inventive architectural fantasies is unwarranted. The time has come to discard old conceptions and look anew at Late Gothic architecture.

Seville cathedral - Southeastern facade

Source: Wikipedia

Gothic architecture - Brick Gothic c. 1350–c. 1400

Gothic architecture - Brick Gothic c. 1350–c. 1400

Malbork Castle on the Nogat river in Pomerania, Poland — the world’s largest Brick Gothic castle

Overview:

Brick Gothic (German: Backsteingotik, Polish: Gotyk ceglany) is a specific style of Gothic architecture common in Northern Europe, especially in Northern Germany and the regions around the Baltic Sea, which do not have natural stone resources. The buildings are essentially built using bricks.

Brick Gothic buildings are found in Belarus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

As the use of baked red brick in Northern Europe dates from the 12th century, the oldest such buildings are classified as the Brick Romanesque. In the 16th century, Brick Gothic was superseded by Brick Renaissance architecture.

Brick Gothic is characterised by the lack of figural architectural sculpture, widespread in other styles of Gothic architecture; and by its creative subdivision and structuring of walls, using built ornaments and the colour contrast between red bricks, glazed bricks and white lime plaster.

Many of the old town centres dominated by Brick Gothic, as well as some individual structures, have been listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Distribution

Brick architecture is found primarily in areas that lack sufficient natural supplies of building stone. This is the case across the Northern European Lowlands. Since the German part of that region (the Northern German Plain, except Westphalia and the Rhineland) is largely concurrent with the area influenced by the Hanseatic League, Brick Gothic has become a symbol of that powerful alliance of cities. Along with the Low German Language, it forms a major defining element of the Northern German cultural area, especially in regard to late city foundations and the areas of colonisation north and east of the Elbe. In the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, that cultural area extended throughout the southern part of the Baltic region and had a major influence on Scandinavia. The southernmost Brick Gothic structure in Germany is the Bergkirche (mountain church) of Altenburg in Thuringia.

Brick Gothic in Poland

Brick Gothic in Poland is sometimes described as belonging to the Polish Gothic style. Though, the vast majority of Gothic buildings within the borders of modern Poland are brick-built, the term also encompasses non-brick Gothic structures, such as the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, which is mostly stone-built. The principle characteristic of the Polish Gothic style is its limited use of stone work to complement the main brick construction. Stone was primarily utilized for window and door frames, arched columns, ribbed vaults, foundations and ornamentation, while brick remained the core building material used to erect walls and cap ceilings. This limited use of stone, as a supplementary building material, was most prevalent in Lesser Poland and was made possible by an abundance of limestone in the region.

Corpus Christi Basilica and monastery in Kraków, Poland

Development

Brick architecture became prevalent in the 12th century, still within the Romanesque architecture period. Wooden architecture had long dominated in northern Germany but was inadequate for the construction of monumental structures. Throughout the area of Brick Gothic, half-timbered architecture remained typical for smaller buildings, especially in rural areas, well into modern times.

In the areas dominated by the Welfs, the use of brick to replace natural stone began with cathedrals and parish churches at Oldenburg (Holstein), Segeberg, Ratzeburg, and Lübeck. Henry the Lion laid the foundation stone of the Cathedral in 1173.

In the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the lack of natural stone and the distance to the Baltic Sea (which, like the rivers, could be used for transporting heavy loads) made the need for alternative materials more pressing. Brick architecture here started with the Cathedral of Brandenburg, begun in 1165 under Albert the Bear. Jerichow Monastery ( then a part of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg ), with construction started as early as 1148, plays a key role regarding Brick Gothic in Brandenburg.

Characteristics of Brick Gothic

Romanesque brick architecture remained closely connected with contemporary stone architecture and simply translated the latter's style and repertoire into the new material. In contrast, Brick Gothic developed its own typical style, characterised by the reduction in available materials: the buildings were often bulky and of monumental size, but rather simple as regards their external appearance, lacking the delicacy of areas further south. Nonetheless, they were strongly influenced by the cathedrals of France and by the gothique tournaisien or Schelde Gothic of the County of Flanders.

Later, techniques that led to a more elaborate structuring of the churches became prevalent: recessed wall areas were often painted with lime plaster, creating a marked contrast to the darker brick-built areas. Furthermore, special shaped bricks were produced to facilitate the imitation of architectural sculpture.

Treptower Tor, one of the 4 unique Brick Gothic city gates in Neubrandenburg, Germany

Source: Wikipedia

Gothic architecture - Manueline 1495-1521 (Portugal & colonies)

Gothic architecture - Manueline 1495-1521 (Portugal & colonies)

The Tower of Belém, in Lisbon, is one of the most representative examples of Manueline style

Overview:

The Manueline (Portuguese: estilo manuelino, IPA: [ɨʃˈtilu mɐnweˈɫinu]), or Portuguese late Gothic, is the sumptuous, composite Portuguese style of architectural ornamentation of the first decades of the 16th century, incorporating maritime elements and representations of the discoveries brought from the voyages of Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral. This innovative style synthesizes aspects of Late Gothic architecture with influences of the Spanish Plateresque style, Mudéjar, Italian urban architecture, and Flemish elements. It marks the transition from Late Gothic to Renaissance. The construction of churches and monasteries in Manueline was largely financed by proceeds of the lucrative spice trade with Africa and India.

The style was given its name, many years later, by Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen, Viscount of Porto Seguro, in his 1842 book, Noticia historica e descriptiva do Mosteiro de Belem, com um glossario de varios termos respectivos principalmente a architectura gothica, in his description of the Jerónimos Monastery. Varnhagen named the style after King Manuel I, whose reign (1495–1521) coincided with its development. The style was much influenced by the astonishing successes of the voyages of discovery of Portuguese navigators, from the coastal areas of Africa to the discovery of Brazil and the ocean routes to the Far East, drawing heavily on the style and decorations of East Indian temples.

Although the period of this style did not last long (from 1490 to 1520), it played an important part in the development of Portuguese art. The influence of the style outlived the king. Celebrating the newly maritime power, it manifested itself in architecture (churches, monasteries, palaces, castles) and extended into other arts such as sculpture, painting, works of art made of precious metals, faience and furniture.

Characteristics:

his decorative style is characterized by virtuoso complex ornamentation in portals, windows, columns and arcades. In its end period it tended to become excessively exuberant as in Tomar.

Several elements appear regularly in these intricately carved stoneworks:

- elements used on ships: the armillary sphere (a navigational instrument and the personal emblem of Manuel I and also symbol of the cosmos), spheres, anchors, anchor chains, ropes and cables.

- elements from the sea, such as shells, pearls and strings of seaweed.

- botanical motifs such as laurel branches, oak leaves, acorns, poppy capsules, corncobs, thistles.

- symbols of Christianity such as the cross of the Order of Christ (former Templar knights), the military order that played a prominent role and helped finance the first voyages of discovery. The cross of this order decorated the sails of the Portuguese ships.

- elements from newly discovered lands (such as the tracery in the Claustro Real in the Monastery of Batalha, suggesting Islamic filigree work, influenced by buildings in India)

- columns carved like twisted strands of rope

- semicircular arches (instead of Gothic pointed arches) of doors and windows, sometimes consisting of three or more convex curves

- multiple pillars

- eight-sided capitals

- lack of symmetry

- conical pinnacles

- bevelled crenellations

- ornate portals with niches or canopies

Manueline exterior of the Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon

Examples:

When King Manuel I died in 1521, he had funded 62 construction projects. However, much original Manueline architecture in Portugal was lost or damaged beyond restoration in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and subsequent tsunami. In Lisbon, the Ribeira Palace, residence of King Manuel I, and the Hospital Real de Todos os Santos (All-Saints Hospital) were destroyed, along with several churches. The city, however, still has outstanding examples of the style in the Jerónimos Monastery (mainly designed by Diogo Boitac and João de Castilho) and in the small fortress of the Belém Tower (designed by Francisco de Arruda). Both are located close to each other in the Belém neighbourhood. The portal of the Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Velha, in downtown Lisbon, has also survived destruction.

Outside Lisbon, the church and chapter house of the Convent of the Order of Christ at Tomar (designed by Diogo de Arruda) is a major Manueline monument. In particular, the large window of the chapter house, with its fantastic sculptured organic and twisted rope forms, is one of the most extraordinary achievements of the Manueline style.

Other major Manueline monuments include the arcade screens of the Royal Cloister (designed by Diogo Boitac) and the Unfinished Chapels (designed by Mateus Fernandes) at the Monastery of Batalha and the Royal Palace of Sintra.

Other remarkable Manueline buildings include the church of the Monastery of Jesus of Setúbal (one of the earliest Manueline churches) (also designed by Diogo Boitac), the Santa Cruz Monastery in Coimbra, the main churches in Golegã, Vila do Conde, Moura, Caminha, Olivença and portions of the cathedrals of Braga (main chapel), Viseu (rib vaulting of the nave) and Guarda (main portal, pillars, vaulting).

Civil buildings in manueline style exist in Évora, home to the Évora Royal Palace (1525, by Pedro de Trillo, Diogo de Arruda and Francisco de Arruda) and the Castle of Évoramonte (1531) as well as Viana do Castelo, Guimarães and some other towns.

The style was extended to the decorative arts and spread throughout the Portuguese Empire, to the islands of the Azores, Madeira, enclaves in North Africa, Brazil, Goa in Portuguese India and even Macau, China. Its influence is apparent in Southern Spain, the Canary Islands, North Africa and the former Spanish colonies of Peru and Mexico.

Batalha Monastery in Portugal

Source: Wikipedia

Russian architecture - Early Muscovite period (1230–1530)

Russian architecture - Early Muscovite period (1230–1530)

Episcopal palace in Suzdal (15th century)

The Mongols looted the country so thoroughly that even capitals (such as Moscow or Tver) could not afford new stone churches for more than half a century. Novgorod and Pskov escaped the Mongol yoke, however, and evolved into successful commercial republics; dozens of medieval churches (from the 12th century and after) have been preserved in these towns. The churches of Novgorod (such as the Saviour-on-Ilyina-Street, built in 1374), are steep-roofed and roughly carved; some contain magnificent medieval frescoes. The tiny and picturesque churches of Pskov feature many novel elements: corbel arches, church porches, exterior galleries and bell towers. All these features were introduced by Pskov masons to Muscovy, where they constructed numerous buildings during the 15th century (including the Deposition Church of the Moscow Kremlin (1462) and the Holy Spirit Church of the Holy Trinity Lavra, built in 1476).

The 14th-century churches of Muscovy are few, and their ages are disputed. Typical monuments—found in Nikolskoe (near Ruza, possibly from the 1320s) and Kolomna (possibly from the second decade of the 14th century)—are diminutive single-domed fortified churches, built of roughly hewn ("wild") stone and capable of withstanding brief sieges. By the construction of the Assumption Cathedral in Zvenigorod (possibly in 1399), Muscovite masons regained the mastery of pre-Mongol builders and solved some of the construction problems which had puzzled their predecessors. Signature monuments of early Muscovite architecture are found in the Holy Trinity Lavra (1423), Savvin Monastery of Zvenigorod (possibly 1405) and St. Andronik Monastery in Moscow (1427).

By the end of the 15th century Muscovy was so powerful a state that its prestige required magnificent, multi-domed buildings on a par with the pre-Mongol cathedrals of Novgorod and Vladimir. As Russian masters were unable to build anything like them, Ivan III invited Italian masters from Florence and Venice. They reproduced ancient Vladimir structures in three large cathedrals in the Moscow Kremlin, and decorated them with Italian Renaissance motifs. These ambitious Kremlin cathedrals (among them the Dormition and Archangel Cathedrals) were imitated throughout Russia during the 16th century, with new edifices tending to be larger and more ornate than their predecessors (for example, the Hodegetria Cathedral of Novodevichy Convent from the 1520s).

Apart from churches, many other structures date from Ivan III's reign. These include fortifications (Kitai-gorod, the Kremlin (its current towers were built later), Ivangorod), towers (Ivan the Great Bell Tower) and palaces (the Palace of Facets and the Uglich Palace). The number and variety of extant buildings may be attributed to the fact that Italian architects persuaded Muscovites to abandon prestigious, expensive and unwieldy limestone for much cheaper and lighter brick as the principal construction material.

Example: Dormition Cathedral, Moscow

south façade, viewed from Cathedral Square

The Cathedral of the Dormition (Russian: Успенский Собор, or Uspensky sobor) is a Russian Orthodox church dedicated to the Dormition of the Theotokos. It is located on the north side of Cathedral Square of the Moscow Kremlin in Russia. The Cathedral is regarded as the mother church of Muscovite Russia. In its present form it was constructed between 1475–79 at the behest of the Moscow Grand Duke Ivan III by the Italian architect Aristotele Fioravanti. From 1547 to 1896 it is where the Coronation of the Russian monarch was held. In addition, it is the burial place for most of the Moscow Metropolitans and Patriarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Dormition Cathedral is a tremendous 6 pillared building with 5 apses and 5 domes. It was modeled after the Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir, in that it made extensive use of limestone masonry on a high limestone base, and was laid out as a three nave church with a vaulted cross-dome. It is built of well-trimmed white-stone blocks. However, Fioravanti did not use cantilever vaults as was common in Russian architecture, but introduced groin vaults and transverse arches. For the upper portion of the building, he used specially-made bricks, larger than the standard Russian size, which reduced weight and allowed for more slender arch supports. Thus, the easternmost pair of columns in front of the apses are typically Russian in the use of massive rectangular open piers, whereas the remaining four are simpler Corinthian columns. The slim shape of these columns contributes significantly to the light, spacious effect of the interior.

Inside, the church decoration is dominated by its fresco painting. The huge iconostasis dates from 1547, but its two highest tiers are later additions from 1626 and 1653/1654 under Patriarch Nikon. It addition to its liturgical function, the iconostasis also served as a sort of trophy wall, in that Russian Tsars would add the most important icons from cities they had conquered to its collection. One of the oldest, icons with the bust of Saint George dates from the 12th century and was transferred to Moscow by Tsar Ivan IV on the conquest of the city of Veliky Novgorod in 1561.

However, one of the most important cult images of the Russian Orthodox Church, the Theotokos of Vladimir kept at the Cathedral from 1395-1919 is now at the Tretyakov Gallery.

Near the south entrance to the Cathedral is the Monomach Throne of Ivan IV (1551).

Source: Wikipedia

Gothic architecture - Sondergotik (1350 - 1550)

Gothic architecture - Sondergotik (1350 - 1550)Sondergotik (Special Gothic) is the style of Late Gothic architecture prevalent in Austria, Bavaria, Saxony and Bohemia between 1350 and 1550. The term was invented by art historian Kurt Gerstenberg in his 1913 work Deutsche Sondergotik, in which he argued that the Late Gothic had a special expression in Germany (especially the South and the Rhineland) marked by the use of the hall church or Hallenkirche. At the same time the style forms part of the International Gothic style in its origins.

The style was contemporaneous with several unique local styles of Gothic: the flamboyant in France, the perpendicular in England, the Manueline in Portugal, and the Isabelline in Spain. Like these, the Sondergotik showed an attention to detail both within and without. In many Sondergotik buildings, fluidity and a wood-like quality were stressed in carving and decoration, particularly on vaults. The rib patterns of Sondergotik vaults are elaborate and often curved (in plan), sometimes using broken and flying ribs (features extremely rare in other regions). Outside, the buildings tended towards mass buttressing.

Among the most famous Sondergotik constructions is Saint Barbara Church in Kutná Hora (modern Czech Republic), built by the Parlers, a family of masons.

Example: St. Barbara's Church in Kutná Hora, Czech Republic

Saint Barbara's Church (Czech: Chrám svaté Barbory) is a Roman Catholic church in Kutná Hora (Bohemia) in the style of a Cathedral, and is sometimes referred to as the Cathedral of St Barbara (Czech: Katedrál sv. panny Barbory). It is one of the most famous Gothic churches in central Europe and it is a UNESCO world heritage site. St Barbara is the patron saint of miners (among others), which was highly appropriate for a town whose wealth was based entirely upon its silver mines.

Construction began in 1388, but because work on the church was interrupted several times, it was not completed until 1905. The first architect was probably Johann Parler, son of Peter Parler. Work on the building was interrupted for more than 60 years during the Hussite Wars and when work resumed in 1481, Matěj Rejsek, Benedikt Rejt and Mikuláš Parler, assumed responsibility.

The original design was for a much larger church, perhaps twice the size of the present building. Construction, however, depended on the prosperity of the town's silver mines, which became much less productive. So, in 1588, the three-peaked roof had been completed and a provisional wall was constructed. A little later it was occupied by Jesuits who gradually changed the structure into Baroque style, though parts still remain in Gothic style.

The final process of repair and completion took place at the end of the 19th century, under architects J. Mocker and L. Labler.

Originally there were eight radial chapels with trapezoidal interiors. Later on, the choir was constructed, supported by double-arched flying buttresses.

Internal points of note are the glass windows, altars, pulpits and choir stalls. Medieval frescoes depicting the secular life of the medieval mining town and religious themes have been partially preserved.

Source: Wikipedia

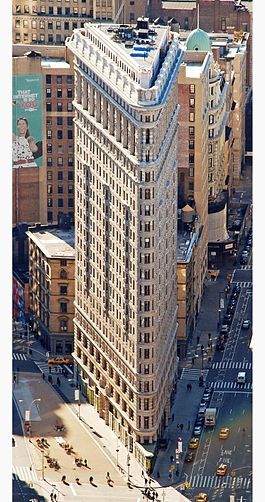

Let's not forget the fantastic Flatiron building, an icon of New York City skyscrapers.

Flatiron Building

The Flatiron Building, originally the Fuller Building, is a triangular 22-story steel-framed landmarked building located at 175 Fifth Avenue in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, and is considered to be a groundbreaking skyscraper. Upon completion in 1902, it was one of the tallest buildings in the city at 20 floors high, and one of only two skyscrapers north of 14th Street – the other being the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, one block east. The building sits on a triangular block formed by Fifth Avenue, Broadway and East 22nd Street, with 23rd Street grazing the triangle's northern (uptown) peak. As with numerous other wedge-shaped buildings, the name "Flatiron" derives from its resemblance to a cast-iron clothes iron.

The building, which has been called "one of the world's most iconic skyscrapers, and a quintessential symbol of New York City", anchors the south (downtown) end of Madison Square and the north (uptown) end of the Ladies' Mile Historic District. The neighborhood around it is called the Flatiron District after its signature building, which has become an icon of New York City. The building was designated a New York City landmark in 1966, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989.

(Source: Wikipedia)

This is a very interesting photographic study of New York City - from 1930 until today - fascinating really:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/classic-n...

http://www.wsj.com/articles/classic-n...

I just finished this book about the 1920s in NYC and the rise of the skyscrapers. A lot of very interesting information about the architecture of the City. Recommended.

I just finished this book about the 1920s in NYC and the rise of the skyscrapers. A lot of very interesting information about the architecture of the City. Recommended. by

by

Donald L. Miller

Donald L. Miller

Bentley wrote: "This is a very interesting photographic study of New York City - from 1930 until today - fascinating really:

Bentley wrote: "This is a very interesting photographic study of New York City - from 1930 until today - fascinating really:http://www.wsj.com/articles/classic-n......"

This is great! :)

Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture

The dome of Florence Cathedral (the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore)

Renaissance architecture is the architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 17th centuries in different regions of Europe, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought and material culture. Stylistically, Renaissance architecture followed Gothic architecture and was succeeded by Baroque architecture. Developed first in Florence, with Filippo Brunelleschi as one of its innovators, the Renaissance style quickly spread to other Italian cities. The style was carried to France, Germany, England, Russia and other parts of Europe at different dates and with varying degrees of impact.

Renaissance style places emphasis on symmetry, proportion, geometry and the regularity of parts as they are demonstrated in the architecture of classical antiquity and in particular ancient Roman architecture, of which many examples remained. Orderly arrangements of columns, pilasters and lintels, as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical domes, niches and aedicules replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of medieval buildings.

Development in Italy – architectural influences

Italy of the 15th century, and the city of Florence in particular, was home to the Renaissance. It is in Florence that the new architectural style had its beginning, not slowly evolving in the way that Gothic grew out of Romanesque, but consciously brought to being by particular architects who sought to revive the order of a past "Golden Age". The scholarly approach to the architecture of the ancient coincided with the general revival of learning. A number of factors were influential in bringing this about.

Italian architects had always preferred forms that were clearly defined and structural members that expressed their purpose. Many Tuscan Romanesque buildings demonstrate these characteristics, as seen in the Florence Baptistery and Pisa Cathedral.

Italy had never fully adopted the Gothic style of architecture. Apart from the Cathedral of Milan, (influenced by French Rayonnant Gothic), few Italian churches show the emphasis on vertically, the clustered shafts, ornate tracery and complex ribbed vaulting that characterise Gothic in other parts of Europe.

The presence, particularly in Rome, of ancient architectural remains showing the ordered Classical style provided an inspiration to artists at a time when philosophy was also turning towards the Classical.

Architectural theory

During the Renaissance, architecture became not only a question of practice, but also a matter for theoretical discussion. Printing played a large role in the dissemination of ideas.

The first treatise on architecture was De re aedificatoria ("On the Art of Building") by Leon Battista Alberti in 1450. It was to some degree dependent on Vitruvius's De architectura, a manuscript of which was discovered in 1414 in a library in Switzerland. De re aedificatoria in 1485 became the first printed book on architecture.

Sebastiano Serlio (1475 – c. 1554) produced the next important text, the first volume of which appeared in Venice in 1537; it was entitled Regole generali d'architettura ("General Rules of Architecture"). It is known as Serlio's "Fourth Book" since it was the fourth in Serlio's original plan of a treatise in seven books. In all, five books were published.

In 1570, Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) published I quattro libri dell'architettura ("The Four Books of Architecture") in Venice. This book was widely printed and responsible to a great degree for spreading the ideas of the Renaissance through Europe. All these books were intended to be read and studied not only by architects, but also by patrons.

Principal phases

Historians often divide the Renaissance in Italy into three phases. Whereas art historians might talk of an "Early Renaissance" period, in which they include developments in 14th-century painting and sculpture, this is usually not the case in architectural history. The bleak economic conditions of the late 14th century did not produce buildings that are considered to be part of the Renaissance. As a result, the word "Renaissance" among architectural historians usually applies to the period 1400 to ca. 1525, or later in the case of non-Italian Renaissances.

Historians often use the following designations:

1. Renaissance (ca. 1400–1500); also known as the Quattrocento[8] and sometimes Early Renaissance

2. High Renaissance (ca.1500–1525)

3. Mannerism (ca. 1520–1600)

Source: Wikipedia

For further research:

by Christy Anderson (no photo)

by Christy Anderson (no photo) by

by

Ross King

Ross King by Alexander Markschies (no photo)

by Alexander Markschies (no photo)

Tudor architecture

Tudor architecture

Outside view of King's College Chapel, Cambridge, showing the distinctive Tudor arch

The Tudor architectural style is the final development of Medieval architecture in England, during the Tudor period (1485–1603) and even beyond. It followed the Perpendicular style and, although superseded by Elizabethan architecture in domestic building of any pretensions to fashion, the Tudor style long retained its hold on English taste. Nevertheless, 'Tudor style' is an awkward style-designation, with its implied suggestions of continuity through the period of the Tudor dynasty and the misleading impression that there was a style break at the accession of Stuart James I in 1603.

The four-centered arch, now known as the Tudor arch, was a defining feature. Some of the most remarkable oriel windows belong to this period. Mouldings are more spread out and the foliage becomes more naturalistic. During the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, many Italian artists arrived in England; their decorative features can be seen at Hampton Court, Layer Marney Tower, Sutton Place, and elsewhere. However, in the following reign of Elizabeth I, the influence of Northern Mannerism, mainly derived from books, was greater. Courtiers and other wealthy Elizabethans competed to build prodigy houses that proclaimed their status.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries redistributed large amounts of land to the wealthy, resulting in a secular building boom, as well as a source of stone. The building of churches had already slowed somewhat before the English Reformation, after a great boom in the previous century, but was brought to a nearly complete stop by the Reformation. Civic and university buildings became steadily more numerous in the period, which saw general increasing prosperity. Brick was something of an exotic and expensive rarity at the beginning of the period, but during it became very widely used in many parts of England, even for modest buildings, gradually restricting traditional methods such as wood framed daub and wattle and half-timbering to the lower classes by the end of the period.

Example: King's College Chapel, Cambridge

Side view of the Chapel from inside the college

King's College Chapel is the chapel at King's College in the University of Cambridge. It is considered one of the finest examples of late Perpendicular Gothic English architecture. The chapel was built in phases by a succession of kings of England from 1446 to 1515, a period which spanned the Wars of the Roses. The chapel's large stained glass windows were not completed until 1531, and its early Renaissance rood screen was erected in 1532–36. The chapel is an active house of worship, and home of the King's College Choir. The chapel is a significant tourist site and a commonly used symbol of the city of Cambridge.

The windows of King's College Chapel are some of the finest in the world from their era. There are 12 large windows on each side of the chapel, and larger windows at the east and west ends. With the exception of the west window, they are by Flemish hands and date from 1515 to 1531. Barnard Flower, the first non-Englishman appointed as the King's Glazier, completed four windows. Gaylon Hone and three partners (two English and one Flemish) are responsible for the east window and 16 others between 1526 and 1531. The final four were made by Francis Williamson and Symon Symondes. The one modern window is that in the west wall, which is by the Clayton and Bell company and dates from 1879.

This large wooden screen, which separates the nave from the altar and supports the chapel organ, was erected in 1532–36 by Henry VIII in celebration of his marriage to Anne Boleyn. The screen is an example of early Renaissance architecture: a striking contrast to the Perpendicular Gothic chapel; Sir Nikolaus Pevsner said it is "the most exquisite piece of Italian decoration surviving in England".

Source: Wikipedia

Russian architecture - Middle Muscovite period (1530–1630)

Russian architecture - Middle Muscovite period (1530–1630)

Church of the Ascension in Kolomenskoe (1532)

In the 16th century, the key development was the introduction of the tented roof in brick architecture. Tent-like roof construction is thought to have originated in northern Russia, since it prevented snow from piling up on wooden buildings during long winters. In wooden churches (even modern ones), this type of roof has been very popular. The first tent-like brick church is the Ascension church in Kolomenskoe (1531), designed to commemorate the birth of Ivan the Terrible. Its design gives rise to speculation; it is likely that this style (never found in other Orthodox countries) symbolized the ambition of the nascent Russian state and the liberation of Russian art from Byzantine canons after Constantinople's fall to the Turks.

Tented churches were popular during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. Two prime examples dating from his reign employ several tents of exotic shapes and colors, arranged in an intricate design: the Church of St John the Baptist in Kolomenskoye (1547) and Saint Basil's Cathedral on Red Square (1561). The latter church unites nine tented roofs in a striking circular composition.

Example: Terem Palace

Facade of the Terem Palace

Terem Palace or Teremnoy Palace (Russian: Теремной дворец) is a historical building in the Moscow Kremlin, Russia, which used to be the main residence of the Russian tsars in the 17th century. Its name is derived from the Greek word τερεμνον (i.e., "dwelling"). Currently, the structure is not accessible to the public, as it belongs to the official residence of the President of Russia.

On the 16th century Aloisio the New constructed the first royal palace on the spot. Only the ground floor survives from that structure, as the first Romanov tsar, Mikhail Feodorovich, had the palace completely rebuilt in 1635–36. The new structure was surrounded by numerous annexes and outbuildings, including the Boyar Platform, Golden Staircase, Golden Porch, and several turrets. On Mikhail's behest, the adjoining Golden Tsaritsa's Chamber constructed back in the 1560s for Ivan IV's wife, was surmounted with 11 golden domes of the Upper Saviour Cathedral. The complex of the palace also incorporates several churches of earlier construction, including the Church of the Virgin's Nativity from the 1360s.

The palace consists of five stories. The third story was occupied by the tsaritsa and her children; the fourth one contained the private apartments of the tsar. The upper story is a tent-like structure where the Boyar Duma convened. The exterior, exuberantly decorated with brick tracery and colored tiles, is brilliantly painted in red, yellow, and orange. The interior used to be painted as well, but the original murals were destroyed by successive fires, particularly the great fire of 1812. In 1837, the interiors were renovated in accordance with old drawings in the Russian Revival style.

Source: Wikipedia

Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture

Façade of the Church of the Gesù, the first truly baroque façade

Baroque architecture is the building style of the Baroque era, begun in late 16th-century Italy, that took the Roman vocabulary of Renaissance architecture and used it in a new rhetorical and theatrical fashion, often to express the triumph of the Catholic Church and the absolutist state. It was characterized by new explorations of form, light and shadow, and dramatic intensity.

Whereas the Renaissance drew on the wealth and power of the Italian courts and was a blend of secular and religious forces, the Baroque was, initially at least, directly linked to the Counter-Reformation, a movement within the Catholic Church to reform itself in response to the Protestant Reformation.

Baroque architecture and its embellishments were on the one hand more accessible to the emotions and on the other hand, a visible statement of the wealth and power of the Church. The new style manifested itself in particular in the context of the new religious orders, like the Theatines and the Jesuits who aimed to improve popular piety.

The architecture of the High Roman Baroque can be assigned to the papal reigns of Urban VIII, Innocent X and Alexander VII, spanning from 1623 to 1667. The three principal architects of this period were the sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini and the painter Pietro da Cortona and each evolved his own distinctively individual architectural expression.

Dissemination of Baroque architecture to the south of Italy resulted in regional variations such as Sicilian Baroque architecture or that of Naples and Lecce. To the north, the Theatine architect Camillo-Guarino Guarini, Bernardo Vittone and Sicilian born Filippo Juvarra contributed Baroque buildings to the city of Turin and the Piedmont region.

A synthesis of Bernini, Borromini and Cortona’s architecture can be seen in the late Baroque architecture of northern Europe which paved the way for the more decorative Rococo style.

By the middle of the 17th century, the Baroque style had found its secular expression in the form of grand palaces, first in France—with the Château de Maisons (1642) near Paris by François Mansart—and then throughout Europe.

During the 17th century, Baroque architecture spread through Europe and Latin America, where it was particularly promoted by the Jesuits.

Catedral Metropolitana, Mexico City, started in 1573

Precursors and features of Baroque architecture

Michelangelo's late Roman buildings, particularly St. Peter's Basilica, may be considered precursors to Baroque architecture. His pupil Giacomo della Porta continued this work in Rome, particularly in the façade of the Jesuit church Il Gesù, which leads directly to the most important church façade of the early Baroque, Santa Susanna (1603), by Carlo Maderno

Distinctive features of Baroque architecture can include:

- In churches, broader naves and sometimes given oval forms

- Fragmentary or deliberately incomplete architectural elements

- Dramatic use of light; either strong light-and-shade contrasts (chiaroscuro effects) as at the church of Weltenburg Abbey, or uniform lighting by means of several windows (e.g. church of Weingarten Abbey)

- Opulent use of colour and ornaments (putti or figures made of wood (often gilded), plaster or stucco, marble or faux finishing)

- Large-scale ceiling frescoes

- An external façade often characterized by a dramatic central projection

- The interior is a shell for painting, sculpture and stucco (especially in the late Baroque)

- Illusory effects like trompe l'oeil (an art technique involving extremely realistic imagery in order to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects appear in three dimensions) and the blending of painting and architecture

- Pear-shaped domes in the Bavarian, Czech, Polish and Ukrainian Baroque

- Marian and Holy Trinity columns erected in Catholic countries, often in thanksgiving for ending a plague

Source: Wikipedia

For further research:

by Rolf Toman (no photo)

by Rolf Toman (no photo) by Frederique Lemerle-Pauwels (no photo)

by Frederique Lemerle-Pauwels (no photo) by Claudia Zanlungo (no photo)

by Claudia Zanlungo (no photo)

Baroque architecture - Italian Baroque architecture - Central Italy

Baroque architecture - Italian Baroque architecture - Central Italy

Palazzo Barberini, Rome

The sacred architecture of the Baroque period had its beginnings in the Italian paradigm of the basilica with crossed dome and nave. One of the first Roman structures to break with the Mannerist conventions exemplified in the Gesù, was the church of Santa Susanna, designed by Carlo Maderno. The dynamic rhythm of columns and pilasters, central massing, and the protrusion and condensed central decoration add complexity to the structure. There is an incipient playfulness with the rules of classic design, still maintaining rigor. They had domed roofs.

The same emphasis on plasticity, continuity and dramatic effects is evident in the work of Pietro da Cortona, illustrated by San Luca e Santa Martina (1635) and Santa Maria della Pace (1656). The latter building, with concave wings devised to simulate a theatrical set, presses forward to fill a tiny piazza in front of it. Other Roman ensembles of the period are likewise suffused with theatricality, dominating the surrounding cityscape as a sort of theatrical environment.

Probably the best known example of such an approach is trapezoidal Saint Peter's Square, which has been praised as a masterstroke of Baroque theatre. The square is shaped by two colonnades, designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini on an unprecedented colossal scale to suit the space and provide emotions of awe. Bernini's own favourite design was the polychromatic oval church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale (1658), which, with its lofty altar and soaring dome, provides a concentrated sampling of the new architecture. His idea of the Baroque townhouse is typified by the Palazzo Barberini (1629) and Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi (1664), both in Rome.

The facade of Santa Susanna, Rome

Bernini's chief rival in the papal capital was Francesco Borromini, whose designs deviate from the regular compositions of the ancient world and Renaissance even more dramatically. Acclaimed by later generations as a revolutionary in architecture, Borromini condemned the anthropomorphic approach of the 16th century, choosing to base his designs on complicated geometric figures (modules). Borromini's architectural space seems to expand and contract when needed, showing some affinity with the late style of Michelangelo. His iconic masterpiece is the diminutive church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, distinguished by a corrugated oval plan and complex convex-concave rhythms. A later work, Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza, displays the same antipathy to the flat surface and playful inventiveness, epitomized by a corkscrew lantern dome.

Following the death of Bernini in 1680, Carlo Fontana emerged as the most influential architect working in Rome. His early style is exemplified by the slightly concave façade of San Marcello al Corso). Fontana's academic approach, though lacking in the dazzling inventiveness of his Roman predecessors, exerted substantial influence on Baroque architecture both through his prolific writings and through a number of architects whom he trained and who would disseminate the Baroque idioms throughout 18th-century Europe.

The 18th century saw the capital of Europe's architectural world transferred from Rome to Paris. The Italian Rococo, which flourished in Rome from the 1720s onward, was profoundly influenced by the ideas of Borromini. The most talented architects active in Rome — Francesco de Sanctis (Spanish Steps, 1723) and Filippo Raguzzini (Piazza Sant'Ignazio, 1727) — had little influence outside their native country, as did numerous practitioners of the Sicilian Baroque, including Giovanni Battista Vaccarini, Andrea Palma, and Giuseppe Venanzio Marvuglia. (Source: Wikipedia)

Books mentioned in this topic

Representing Women (other topics)Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (other topics)

Morality and Architecture: The Development of a Theme in Architectural History and Theory from the Gothic Revival to the Modern Movement (other topics)

A History of Western Architecture, 4th edition (other topics)

Baroque: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Linda Nochlin (other topics)Linda Nochlin (other topics)

David Watkin (other topics)

David Watkin (other topics)

Rolf Toman (other topics)

More...

Overview:

The Decorated Period in architecture (also known as the Decorated Gothic, or simply "Decorated") is a name given specifically to a division of English Gothic architecture. Traditionally, this period is broken into two periods: the "Geometric" style (1250–90) and the "Curvilinear" style (1290–1350).

Elements of the style

Decorated architecture is characterised by its window tracery. Elaborate windows are subdivided by closely spaced parallel mullions (vertical bars of stone), usually up to the level at which the arched top of the window begins. The mullions then branch out and cross, intersecting to fill the top part of the window with a mesh of elaborate patterns called tracery, typically including trefoils and quatrefoils. The style was geometrical at first and flowing in the later period, owing to the omission of the circles in the window tracery. This flowing or flamboyant tracery was introduced in the first quarter of the 14th century and lasted about fifty years. This evolution of decorated tracery is often used to subdivide the period into an earlier "Geometric" and later "Curvilinear" period.