Art Lovers discussion

Introduce an Artist and/or Work

>

Why I like Mannerism

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Yes, but the best book I recommend for an overview of the period is Mannerism by John Shearman

Yes, but the best book I recommend for an overview of the period is Mannerism by John Shearmanhttp://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17...

Two of my favorite mannerists works (here) are –

Two of my favorite mannerists works (here) are –[image error]

Pietro Francavilla, Venus with a Nymph and Satyr, 1600

In Avery Memorial (the first American museum interior in the International Style, 1934) is an ornate pool with a fountain, featuring a magnificent marble group of Venus with a nymph, a satyr, and two dolphins, signed and dated 1600 by the Mannerist sculptor Pietro Francavilla. Director “Chick” Austin (who designed this interior) deliberately wanted to contrast the smooth, rectilinear lines of the cantilever balconies with this beautiful mannerist sculpture.

This was the last of 13 marble statues commissioned by Abbot Antonio Bracci of Rovezzano. The others reside in London, at Kensington Palace, and Windsor Castle. Director “Chick” Austin discovered it at the Fogg Museum.

[image error]

Bernardo Strozzi, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615

This is an early religious work done by Strozzi.

Monica,

Monica, Mannerist art seems so graceful to me; especially in color and composition. Is this one of the things that appeals to you?

Monica, can you pick one mannerist artist who is your favorite?

Monica, can you pick one mannerist artist who is your favorite?Are you drawn to the colors or the elongated figures?

We just returned a loan (from the Prado) of the painting below.

The colors in it were so vibrant that you would think it was painted recently.

El Greco, The Holy Family with Saint Anne and the Infant John the Baptist, c. 1595/1600

Yes, Divvy, it is all about grace, that's part of the definition of maniera and tongue-in-cheek aspects of architecture say something about it, too. I'm especially fond of work from the 1st quarter of the 16th century, and, as it progresses more toward baroque, it looses it's sensuality and attraction for me. Giulio Romano played tricks all over Palazzo Te. Symbolism fascinates me, too. Symbolism in the Unicorn tapestries attracted me before I knew anything about mannerism. Girolamo da Carpi, Buontalenti, Baccio Bandinelli, Rosso, Pontormo all fascinate me. Detailed dissertations involving history and symbolism can transfix me for weeks/months on end. Palma Vecchio, Guilio Romano, Perino del Vaga and Baldassare Peruzzi ... are like all my dead boyfriends. I read so much about them they are practically alive to me. It's not for everybody, I admit. Graham Smith, a brilliant historian (whose Scottish accent didn't deter me) instilled his passion for the period in me during college. Smith is so bright, so very, very good, and absolutely without ego. I was blessed to be in his class when he first came as a guest prof from Princeton to Ann Arbor.

Yes, Divvy, it is all about grace, that's part of the definition of maniera and tongue-in-cheek aspects of architecture say something about it, too. I'm especially fond of work from the 1st quarter of the 16th century, and, as it progresses more toward baroque, it looses it's sensuality and attraction for me. Giulio Romano played tricks all over Palazzo Te. Symbolism fascinates me, too. Symbolism in the Unicorn tapestries attracted me before I knew anything about mannerism. Girolamo da Carpi, Buontalenti, Baccio Bandinelli, Rosso, Pontormo all fascinate me. Detailed dissertations involving history and symbolism can transfix me for weeks/months on end. Palma Vecchio, Guilio Romano, Perino del Vaga and Baldassare Peruzzi ... are like all my dead boyfriends. I read so much about them they are practically alive to me. It's not for everybody, I admit. Graham Smith, a brilliant historian (whose Scottish accent didn't deter me) instilled his passion for the period in me during college. Smith is so bright, so very, very good, and absolutely without ego. I was blessed to be in his class when he first came as a guest prof from Princeton to Ann Arbor. We were discussing Friedlander who was instrumental in removing some of the stigma from maniera.

Monica wrote: "Yes, Divvy, it is all about grace, that's part of the definition of maniera and tongue-in-cheek aspects of architecture say something about it, too. I'm especially fond of work from the 1st quarter..."

Monica wrote: "Yes, Divvy, it is all about grace, that's part of the definition of maniera and tongue-in-cheek aspects of architecture say something about it, too. I'm especially fond of work from the 1st quarter..."Great post -- !

The Shearman book is great. It formulates a rigorous definition of what mannerism meant in its Italian historical context. The term therefore becomes something more than just an art-historical catch-all for things that don't fit into the categories of Renaissance or baroque.

The Shearman book is great. It formulates a rigorous definition of what mannerism meant in its Italian historical context. The term therefore becomes something more than just an art-historical catch-all for things that don't fit into the categories of Renaissance or baroque. Shearman, for instance, would omit El Greco from the discussion entirely. El Greco's work was formed and inspired by different cultural forces from the ones that Sherman identifies in Italian mannerism and functioned in a very different context.

The stigma of mannerism outlived Max Friedlaender. When Philippe de Montebello was a young curator at the Met in the 1960s, he spotted a top-quality work by Rosso Fiorentino for sale by a New York dealer. He went to his boss, Theodore Rousseau, the Met's chief curator, to recommend that the museum purchase the picture, as the Met's collection was (and still is) extremely weak in this area. Rousseau said, "Oh, no. Certainly not. It's mannered." End of discussion.

There's a portrait at Cranbrook House that iirc was identified as a Rosso and my heart stopped. It didn't seem possible. Graham Smith drove to Bloomfield Hills with a colleague from Ann Arbor to examine it. It was many years ago so I'd have to contact the curator to remember exact details, but, even though the painting was from the period and wonderful, Duveen had not been 100% correct in the identification.

There's a portrait at Cranbrook House that iirc was identified as a Rosso and my heart stopped. It didn't seem possible. Graham Smith drove to Bloomfield Hills with a colleague from Ann Arbor to examine it. It was many years ago so I'd have to contact the curator to remember exact details, but, even though the painting was from the period and wonderful, Duveen had not been 100% correct in the identification.

I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know.

I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know. I'm raising my coffee cup to Heather right now for starting and keeping this thing going.

Divvy wrote: "I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know.

Divvy wrote: "I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know. I'm raising my coffee cup to Heather right now for starting and keeping this thing going."

I second that.... Finding this group has been like stumbling into a university education!

Jonathan wrote: "Shearman, for instance, would omit El Greco from the discussion entirely. El Greco's work was formed and inspired by different cultural forces from the ones that Sherman identifies in Italian mannerism and functioned in a very different context.

Jonathan wrote: "Shearman, for instance, would omit El Greco from the discussion entirely. El Greco's work was formed and inspired by different cultural forces from the ones that Sherman identifies in Italian mannerism and functioned in a very different context."

Well good. I was always uncomfortable with including El Greco. It always seemed to me that long slender figures were about all he had in common with the Italians. But hey, what do I know? I'm just a studio artist with dirty fingernails.

Yes, El Greco is considered mannerist by some people, but to my eye, not. The names I mention are some of the finest.

Yes, El Greco is considered mannerist by some people, but to my eye, not. The names I mention are some of the finest.After the sack of rome in 1527 many of the great artists were dispersed to other cities in Italy and Primaticcio went to France.

That is interesting - and now I understand the title of that book by Chastel which you like. --

That is interesting - and now I understand the title of that book by Chastel which you like. -- The French attack on Sforza is what flushed Leonardo out of Milan.

And it was the sacking of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 that sent many Byzantine scholars (and texts) scurrying westwards to places like Venice -- which more than anything else is what established the study of Greek in the West. Before that, there were only a very few latinate scholars competent in Greek.

A similar process occurred as a result of WWII, which sent many European scholars in all fields to America -- especially (though not exclusively) from Germany -- many German Jews, for example, ended up teaching for years at the nation's Historically Black Colleges and Universities -- not everyone could find a position at Harvard or UCLA, of course... It took probably 40 years or two generations for Continental universities to heal themselves. It rented the continuity of teaching, among other things.

War, as Céline said, being primarily "the movement of peoples"...

Monica wrote: "So true. I wonder what the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are going to do."

Monica wrote: "So true. I wonder what the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are going to do."I'll avoid politics...; and modern wars, in any case, are profoundly different from the "migratory feasts" of the past -- but if you think of the great sweeping movements in history - many of them have had these population aspects.

Monica wrote: "Carol, I really like that sculpture in message 4. Where is it? In CT?"

Monica wrote: "Carol, I really like that sculpture in message 4. Where is it? In CT?"Its at the Wadsworth Atheneum (of course!) in the Avery Memorial Building.

No, not Avery. The Morgan Memorial is closed (not completely). The front of the first floor near Main Street is open with one small gallery currently featuring "Sol LeWitt: Hartford's Native Son."

No, not Avery. The Morgan Memorial is closed (not completely). The front of the first floor near Main Street is open with one small gallery currently featuring "Sol LeWitt: Hartford's Native Son."

Jonathan wrote: "Shearman, for instance, would omit El Greco from the discussion entirely. El Greco's work was formed and inspired by different cultural forces from the ones that Sherman identifies in Italian mannerism and functioned in a very different context. "

Jonathan wrote: "Shearman, for instance, would omit El Greco from the discussion entirely. El Greco's work was formed and inspired by different cultural forces from the ones that Sherman identifies in Italian mannerism and functioned in a very different context. "So . . . is El Greco is a mannerist artist?

I am no expert in this area but what I remember about mannerist artwork is:

* compositions--dramatic, exaggerated, confusing use of space; almost surreal; sense of fantasy;

* figures --elongated (neck, limbs); distorted/strained postures; sensual/ emotional

* clashing colors

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WMMx6i...

El Greco artworks (3:26)

Carol wrote: "So . . . is El Greco is a mannerist artist? "

Carol wrote: "So . . . is El Greco is a mannerist artist? "Yes, if you think of Mannerism as most 19th and early 20th-century art historians did--a term to describe many different styles of 16th-century art that seemed to be neither Renaissance nor Baroque.

No, if you think of Mannerism as John Shearman defined it.

In his book Mannerism (1967), Shearman painstakingly examined the 16th-century Italian term maniera and argued that it was a phrase "of long standing in the literature of a way of life so stylized that it was in effect a work of art in itself...So, when we turn to look for tendencies in the art of the sixteenth century that may justifiably be called Mannerist, it is logical to demand, so to speak, that these be drenched in maniera and, conversely, should not be marked by qualities that are inimical to it, such as strain, brutality, violence, or overt passion. We require, in fact, poise, refinement and sophistication, and works of art that are polished, rarified and idealized away from the natural: hot-house plants, cultured most carefully. Mannerism should, by tradition, speak a silver-tongued language of articulate, if unnatural, beauty, not one of incoherence, menace and despair; it is, in a phrase, the stylish style."

Of El Greco, Shearman writes, "El Greco is perhaps best considered as an artist who used strongly Mannerist conventions with an increasingly expressive purpose and urgency that is far from characteristic of Mannerism."

So, I think the main qualities that would mark El Greco out as being something other than a Mannerist (for Shearman) are the artist's spiritual ardor and intense religious passion. By turning Mannerist conventions to a deeply-felt examination of the human soul in relation to the divine plan, El Greco certainly became a practitioner of his own individual style, but he was not a practitioner of "the stylish style."

Thanks Jonathan.

Thanks Jonathan. I haven't done anything concerning El Greco. And just the basics concerning mannerist artwork. I'm going to see if I can locate a copy of Shearman's book in the library . . . (I'm still waiting for my Dutch Painting book by Slive -- AbeBooks offered free shipping, so I guess it takes awhile -- lesson learned.)

Yes, Thank you Jonathan! El Greco is an expressionist, his style loose and unrefined, compared to Rosso or Pontormo, and, above all, Parmigianino.

Yes, Thank you Jonathan! El Greco is an expressionist, his style loose and unrefined, compared to Rosso or Pontormo, and, above all, Parmigianino.

The religious struggles in northern Europe affected artists' relationship with religion and fundamental doubts about their world view. What if God is not the center of the universe? What if Catholicism is not the one true religion?

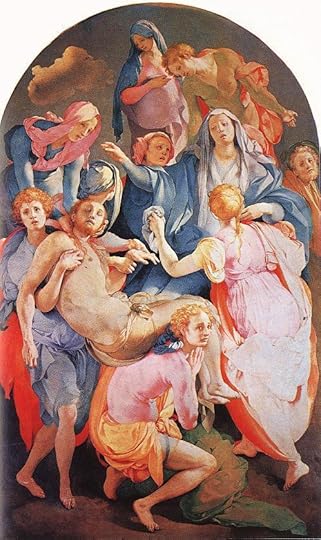

Imagine Pontormo working away in the Capponi Chapel at St. Felicita, doubting the existence of God, not wanting his client or anyone else to see what he was doing. The painting has all that torment and passion, yet it's refined and exquisite. Plus I'd be hard pressed to think of any art that has more beautiful color.

I drove up to the Capponi mansion on the outskirts of Florence to see the house and hopefully the garden but the maid was not sure about letting me in!

Monica wrote: "The religious struggles in northern Europe affected artists' relationship with religion and fundamental doubts about their world view. What if God is not the center of the universe? What if Catholicism is not the one true religion? ..."

Monica wrote: "The religious struggles in northern Europe affected artists' relationship with religion and fundamental doubts about their world view. What if God is not the center of the universe? What if Catholicism is not the one true religion? ..."I get the part about northern artists doubting that Catholicism was the one true religion. But I don't see the connection between the Reformation and "doubting the existence of God." That was definitely not on Martin Luther's agenda, nor on John Calvin's, nor on Ulrich Zwingli's, etc.

The vast majority of northern artists--think of Rembrandt for instance--remained committed to Christianity. And through personal study of the bible, which was available to them in their native languages, rather than just Latin, they were in many cases able to develop a close, personal understanding of the gospels. The bible remained the central text in Rembrandt's work, for instance, throughout the artist's career.

There was, however, a general decline in the production of elaborate, large-scale biblical narratives in northern Europe because of the widespread ban on "icons," which were considered idolatrous in most Reformed churches and therefore inconsistent with the Mosaic commandment against worshiping graven images.

Again, this is an example of a society that took its religion very seriously but in a way quite different from that of their southern neighbors.

Perhaps no one doubted God's existence but there is no doubt the world, even in Italy, was undergoing fundamental change. People were more aware of chaos and imperfections in their world view. (You mean I'm not made in God's image and likeness? God is not the creator of a perfect universe?) The reformation had people riled up and I think that their questioning the status quo attracted me to that period because it parallels with the 1960s and today.

Perhaps no one doubted God's existence but there is no doubt the world, even in Italy, was undergoing fundamental change. People were more aware of chaos and imperfections in their world view. (You mean I'm not made in God's image and likeness? God is not the creator of a perfect universe?) The reformation had people riled up and I think that their questioning the status quo attracted me to that period because it parallels with the 1960s and today.

Hey, Jonathan and everybody,

Hey, Jonathan and everybody,Reformation and Society in Sixteenth Century Europe is a gem of a book on the Reformation because it's a history but great for art lovers because it's wonderfully illustrated.

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/32...

Monica wrote: "the world, even in Italy, was undergoing fundamental change. People were more aware of chaos and imperfections in their world view. (You..."

Monica wrote: "the world, even in Italy, was undergoing fundamental change. People were more aware of chaos and imperfections in their world view. (You..."True enough. The specific differences of opinion that existed between northern and southern Europe as well as between various factions within the Catholic Church of this period were quite complex and sometimes confusing. I think the great virtue of Shearman's book is that instead of generalizing with regard to historical trends, it untangles many complex strains of artistic and societal development and helps to sort out their consequences. Tumult and change, for instance, would explain the advent of the Baroque just as well as Mannerism. Shearman gets down to cases, which is what made his book so important.

AC wrote: "Divvy wrote: "I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know.

AC wrote: "Divvy wrote: "I love reading these discussions. You guys are among the most interesting people I know. I'm raising my coffee cup to Heather right now for starting and keeping this thing going."

..."

Kudos to Heather and all of You for providing so much information about art and the art itself in an insightful,scholarly, down-to earth and respectful manner.

I feel very lucky to be a part of this group.

Thank you Divvy, AC, Jim and everyone else. This group would be nothing without all your wonderful contributions. I agree with Jim, the information provided by you all is very educational, 'insightful, scholarly, and down-to-earth'. And it is addressed in a respectful manner. Thank you all so much.

Thank you Divvy, AC, Jim and everyone else. This group would be nothing without all your wonderful contributions. I agree with Jim, the information provided by you all is very educational, 'insightful, scholarly, and down-to-earth'. And it is addressed in a respectful manner. Thank you all so much.

AC asked me why I like Mannerism and I answered it was too big a question. I didn't want to get into a big spheel. Blow this image up here: http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=h...