Salon des Refusés discussion

Group Readings

>

Hermes The Thief: The Evolution Of A Myth

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Okay, I have the book on order from www.abebooks.com, and it should be crossing the Atlantic from the US to England around now. But since 9/11 it can take up to 5 months for this to happen, as I know from previous experience. Things were much faster in the days of Columbus! So I'll join in the read when the book arrives ...

Okay, I have the book on order from www.abebooks.com, and it should be crossing the Atlantic from the US to England around now. But since 9/11 it can take up to 5 months for this to happen, as I know from previous experience. Things were much faster in the days of Columbus! So I'll join in the read when the book arrives ... All right...I am holding out hope you'll get a copy sooner! Why don't we loosely set the reading up for Feb sometime?

All right...I am holding out hope you'll get a copy sooner! Why don't we loosely set the reading up for Feb sometime?

Well, this book is not easy, Candy. It may be a group read but it will certainly be a group of at most two. Fortunately, I know the Greek alphabet, so can read "kleptein" as kappa lambda epsilon pi etc., and see that it is the first part of "kleptomaniac", "crazy about stealing". Such things help. But my knowledge of Greek things is patchy. More precisely, a few patches scattered over a huge empty space. I'm much better on ancient Rome. Norman Brown's book is more like a gigantic reading list of things you ought to go through to understand him fully.

Well, this book is not easy, Candy. It may be a group read but it will certainly be a group of at most two. Fortunately, I know the Greek alphabet, so can read "kleptein" as kappa lambda epsilon pi etc., and see that it is the first part of "kleptomaniac", "crazy about stealing". Such things help. But my knowledge of Greek things is patchy. More precisely, a few patches scattered over a huge empty space. I'm much better on ancient Rome. Norman Brown's book is more like a gigantic reading list of things you ought to go through to understand him fully.But it is interesting. Let me see ...

I have read Hesiod's Theogony in the Penguin book translation, which also contain his Works and Days and Theognis. (Theognis is a second poet, not to be confused with the poem "Theogony"). I had not looked at Works and Days before.

Brown quotes these nice lines,

"Let no strutting dame delude your mind, flattering you with deceitful words, trying to soften your manhood. He who puts his trust in woman, puts his trust in tricksters."

Here is the clumsy Penguin translation,

"Don't let a woman, wiggling her behind,

And flattering and coaxing, take you in.

She wants your barn: woman is just a cheat."

I can see how the Greek for "strutting" might be rendered as "behind wiggling", but I don't see where the barn comes from.

You're reminded that in those days everyone did farming, and there was a lot of coveting going on. Hence the commandment,

"Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour's."

I can honestly say that there is at least one bit of one commandment I have never broken. I have never coveted my neighbour's ox! I have never thought to myself, "My word, that ox is marvellous, how on earth can I get my hands on it?" (An American would say "That sure is one helluvan ox! ...") But supposing I did covet the thing, and managed to get it. I would have no where to put it because some behind-wiggling woman had used her flattering wiles to get my barn off me.

Such was ancient Greece.

I like his idea of "the institution of cattle raiding" among the ancient Greeks. Suddenly their life is like an old episode of Rawhide. Synopsis: "Trouble hits the the boys at the Damoetas ranch when Thrasymachus and Klisthenes brand a loose steer ..."

So far I'm on page 12.

Wow, that's a lot for just page 12!

Wow, that's a lot for just page 12!You know...this book is very insightful for understanding the criminal mind. Just last night we were watching the singer/songwriter Tupac talk about how the whole town where he was in a penitentiary would fall apart because the prison was the main source of income. NOW that is a sobering thought.

Great notes on this book Martin. I hope we get some interest inspired in our other friends here. I think this book is such a great example of how exciting it is to read and break down the history of storytelling. I'm not sure any ancient story or other narratives ever look the same after reading this kind of analysis.

Okay, I'm really getting into this now.

Okay, I'm really getting into this now. I was intrigued by Greek mythology at about age 11, and absorbed various books, Kingsley's the Heroes and Graves' Greek Myths among them. Graves' retelling, I was shocked to discover, seemed to be all sex and violence. Later I read the abridged Golden Bough, and when at University, Folk Lore in the Old Testament, also by Frazer. I have Nilsson's Mycenaen Origin of Greek Mythology (referred to by Brown in the chapter 1 footnotes), but have never read it. Later I read G.S. Kirk's Myth, which I thought was excellent, in giving a more rational, balanced view.

Graves' ideas are merely "eccentric" (choosing a word to be kind to his memory). With Frazer it is terribly easy to do a hatchet job. Anyway, it is hardly necessary. Who reads Frazer's endless volumes nowadays? Brown however is a fine scholar, and always interesting. Nevertheless, he quotes Frazer, and belonged to that academic world which approached Pagan religion and anthropology through the Classics, and a study of the classical languages.

Problems therefore arise:

1) A reliance on philology. If you study culture through its literature, you move back to a time when nothing was written (or at least, nothing that was written is preserved). So then you start looking at the words themselves, that being all that's left, and start making connections. So keerux is Greek for herald (one of Hermes' functions), and this is related to Sanskrit, karus (bard) so perhaps the office of herald was related to poetry recitation. It may all be true, and it is certainly evidence, but one can easily have serious doubts. Take English: "law" is a Danish word in origin. Okay, but what can you deduce from that? Not that the Danes brought law to England, but perhaps that, after all, they were not as lawless as has been suggested. "dog" appeared from nowhere in the English language, displacing "hound". What can be deduced from that? Nothing that I have ever seen, but it must have an explanation. Philology is full of its own problems, and not an instrument that can be readily applied to answering questions of prehistory.

2) The idea that myth comes from ritual. This is very much Frazer's line, but fails to explain the development of myth into a huge system of stories that cover successive generations of gods and heroes, the way myth explains nature, and the way myth satisfies the human desire for stories and storytelling. I'm not suggesting this is Brown's position, but he clearly sees a strong myth-ritual connection.

3) The idea of the "primitive". Brown uses the word frequently, and at least avoids the "savages" of Frazer, Darwin, and other 19th century thinkers. Primitive Greek gets equated with the primitives studied by 19th and 20th century anthropologists or travellers generally (Frazer himself relied repeatedly on reports of missionaries). But how far does this world equate to the early Greek world? Besides we glimpse the early Greek world only through the eyes of later poets, who might have transformed what they found as much as Shakespeare transforms Geoffrey of Monmouth, his source for Lear and Cymbeline.

But these are early thoughts --- more later.

--- Well into it now. This book is really brilliant. But we need at least one other reader. Candy, did I begin the read a bit soon? If so, I can lie fallow for a week or more.

Yes, Martin...it turns out I need an extra week. Got a lot of paperwork here. Thanks so much...I'm very much looking forward to getting into this though!

Yes, Martin...it turns out I need an extra week. Got a lot of paperwork here. Thanks so much...I'm very much looking forward to getting into this though!

Oh no! Here I am dismissing Frazer and Graves, only to find in the Cymbeline read that they are major influences on Candyminx. And Candy believes folk-memories can last over immense periods, whereas I am really sceptical. So this read (if it begins) might be really interesting, because we'd be in serious disagreement ...

No worries about dismissing Frazer or Graves. I am quite inspired by Frazer and The Golden Bough, but I can see why such work might not be so interesting to others. I really love comparative literature and comparative philosophy. I am a light weight, except that I find the recurring patterns very exciting. I'm medium about Graves. The White Goddess is more interesting as a motif for further study than a kind of hard science. The challenge of course wih comprative philosophy especially in mythology is how can it be a hard science? I am more inspired by the attempts rather than the various professionals "success" Martin.

No worries about dismissing Frazer or Graves. I am quite inspired by Frazer and The Golden Bough, but I can see why such work might not be so interesting to others. I really love comparative literature and comparative philosophy. I am a light weight, except that I find the recurring patterns very exciting. I'm medium about Graves. The White Goddess is more interesting as a motif for further study than a kind of hard science. The challenge of course wih comprative philosophy especially in mythology is how can it be a hard science? I am more inspired by the attempts rather than the various professionals "success" Martin.I'm really enjoying this visit to Hermes The Thief this week as I start to read the book and search online for some supportive sites to the book.

Here is a synopsis of sorts of the Hymn to Hermes:

http://ancienthistory.about.com/libra...

And maybe a little bit from Wiki:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermes

Martin in post #10, you have aptly described the chasm that exists when trying to explore Mythology as a hard science. I have a little more faith than you on words, philology and usages. I most definately believe that mythology (and folklore) can pass through hundreds of years maybe thousands.

I shall provide the following link as a sort of basic evidence to how meaning and knowledge can be transmitted through hundreds of generations. Here is a little excerpt from Margeret Visser. (one of my favourite writers and thinkers). Visser defends English spelling because it records a layer of meaning for the eyes. I believe that the influential English editors chose spellings that reflected several layers of meaning. (actually, Visser wrote a lovely piece once about the relatioshp pf veteran to veterinarian...back to "beast of burden" "vet and why these two very different words were related...comes to mind for this very book about cattle-raiding)

http://www.ucc.asn.au/~jem/quotes/eng...

One of the charming things I like about this book can be shown by this example...within the first few pages...

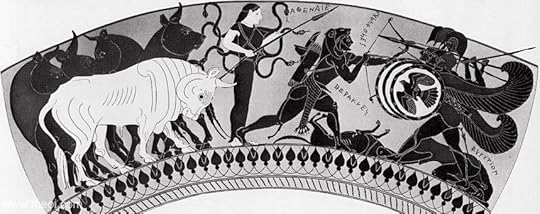

Cattle-raiding, as depicted in Homer, was a public enterprise, led by the kings and participated in by the whole people. It is described as a war-a resort to force, and open force. The institution appears to have been a common heritage of all Indo-European peoples and to have had everywhere the same general characteristics. To cite one illustrative detail: the Sanskrit word for "war" means literally "desire for more cows".

In chapter two...the idea of Hermes associated with "boundaries" is very interesting. The most literal is the stone heaps and mounds to mark land or territory, but I began thinking about how Hermes was associated with inteligence and trickery..."female wiles" and human social transgressions might be another kind of boundary.

In chapter two...the idea of Hermes associated with "boundaries" is very interesting. The most literal is the stone heaps and mounds to mark land or territory, but I began thinking about how Hermes was associated with inteligence and trickery..."female wiles" and human social transgressions might be another kind of boundary.In the mean time I was trying to find pics of boundary markers...the kinds that began to be associated with Hermes.

Hermes, the god of boundary-stone, with his stone-heap and pahallas, was revered not only as a magician who defined his people against the aggressions of strangers, but also as a culture hero. Through contact with strangers and strange places the primitive community supplemented its own limited resources with goods beyond its boundaries.The boundary was crossed not only by goods secured through trade or barter with the strangers living "on the other side", but also enterprising men bent on procuring raw materials from the wasteland that lay between neighbouring communities, or engaged on a "merchant adventure" into alien territory. "Crossing the boundary" was, in the eyes of primitive Greeks, the essence of trade and economic enterprise: the standard Greek words for "buy" and "do business" are derived froma root meaning "beyond, across". Thus Hermes the god of the boundary-stone became the god of trade and craftsmanship. and . consequently, a culture hero and "giver of good things".

Looking for pics of boundary markers...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boundary...

http://www.nativestones.com/cairns.htm

You know...as I'm going through this book and coming here to post..I've been wondering "how do approach" this discussion. And as a matter of fact I got an e-mail asking me if there was a format to follow...a great question.

You know...as I'm going through this book and coming here to post..I've been wondering "how do approach" this discussion. And as a matter of fact I got an e-mail asking me if there was a format to follow...a great question.I was feelign a little devil may care and just dive in nd talk about anything in the book etc. But I wonder...should we work through chapters?

One of the things that this book is notable for is that it set a standard on how to write about Myths. I completely forgot that it was written in 1947. There is somethign about it that feels so contemporary and I think it's the sense of free-flowing style of writing Brown uses. He flies between so many cultures and languages.

I think this book is a great example of E.O. Wilson's argument for interdiciplinary studies and "consilience".

Consilience, or the unity of knowledge (literally a "jumping together" of knowledge), has its roots in the ancient Greek concept of an intrinsic orderliness that governs our cosmos, inherently comprehensible by logical process, a vision at odds with mystical views in many cultures that surrounded the Hellenes. The rational view was recovered during the high Middle Ages, separated from theology during the Renaissance and found its apogee in the Age of Enlightenment. Then, with the rise of the modern sciences, the sense of unity gradually was lost in the increasing fragmentation and specialization of knowledge in the last two centuries. The converse of consilience in this way is Reductionism.

Here is a Wiki page on Wilson's Consilience:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consilie...

I am suggesting these definitions as a option for how to look at Brown

's book.

Brown set out to accomplish a couple of goals with Hermes and the question of whether he succeeds might be an interesting topic as well as the actual myth.

I have one suggestion for a possible theme--theft and social economy. The idea comes from how much analysis of capitalism there is in Life Against Death. Because of this emphasis (which may reflect his Marxism), I've always kind of thought of Brown as approaching myth analysis from the point of view of someone who has a background in economics.

I have one suggestion for a possible theme--theft and social economy. The idea comes from how much analysis of capitalism there is in Life Against Death. Because of this emphasis (which may reflect his Marxism), I've always kind of thought of Brown as approaching myth analysis from the point of view of someone who has a background in economics. So can the argument be made that Hermes as thief is necessary to an economy and thus to social cohesion (whether that be of gods or of humans)? I have a vague idea that one might be able to support the idea employing Georges Battaille's theories on expenditure (think of theft as coerced expenditure).

And if Hermes as thief represents (for Brown) social cohesion, does this reflect Brown's Marxist views, in which private property is seen as an obstacle to social cohesion?

Another possible theme I'd suggest also considers Brown's Hermes in the context of Brown's later ideas in Life Against Death--specifically that of the notion of "polymorphous perversity," which could also be linked to his discussion of Dionysus in the chapter "Apollo and Dionysus." Can the notion of a trickster god be linked to the notion of polymorphous perversity (where the latter is understood from one point of view as "subverting" a "normal" sexual functioning).

And, to return to the notion of social cohesion--how does the Trickster god function in that context? A few different cultures have trickster gods (Loki in Norse mythology comes to mind, and there are a few trickster gods in Native American mythology, and you've got Puck in Shakespeare--Iago, for that matter, and Ted Hughes's Crow--and how about someone like Randall P. MacMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest? So--is the Trickster a villain--and if so, why does society need to produce villains in its mythology? (Note how part of the National Socialist approach to strengthening social cohesion in 1930's Germany was to claim that the "Aryan race" was united in part because its members had common enemies).

And are tricksters only villains? Robin Hood, for instance, is an example of a thieving trickster who was good for the social cohesion of those he represented (but not for those in power, obviously). But with the mention of Robin Hood I'm back to the notion of the redistribution of wealth--and Brown's Marxism, and Battaille's notion of expenditure and potlatches...

So I guess the question I would ask at the moment is how does subversion (including theft) contribute to (or detract from) social cohesion?

I haven't actually started to reread the book yet, so I don't actually know if this something Brown is interested in discussing. Still, he is writing about a particular character associated with a particular set of characteristics--and so I have to wonder whether Brown is working out some ideas about theft, subversion and economy.

Dan,

Dan,Love these questions and ideas for things for us to look for, discuss, explore during our reading. I am totally inspired.

The idea of a co-operative theft economy fits very interestingly into observations and theories of marvin harris in cultural materialism and anthropology.

As a quick note as I would like to link a definition to cultural materialism:

"It is based on the simple premise that human social life is a response to the practical problems of earthly existence" Marvin Harris.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural...

(there might be something to some of Norman O. Brown's ideas from the Frankfurt School. I will look into that and see what I can find)

Something I wanted to add to Dan's idea of watching for the association of economic balances and assimilating "cunning or trickery" into our cultures is one of the major things is this book is the art.

Something I wanted to add to Dan's idea of watching for the association of economic balances and assimilating "cunning or trickery" into our cultures is one of the major things is this book is the art.For me Hermes is a magician associated with art-making. His "magic" seems to have to do with the feeling we might get when art moves us. It's invisible and intangible to explain "why". The idea that a god or goddess has magic inside the artist etc and the viewer to explain the potential power of art is very interesting to me.

In chapter 2,Brown discusses one of the most ancient forms of trade. He says it is silent trade. First we have been introduced, or reminded, that boundary stones were safe places where neighbours or neighbouring villages would meet. Since war or conflict could arise out of competing tribes the idea of placing stones as a neutral meeting spot is a practical idea. It seems there is some kind of formality or ritual of greeting we might have done at these boundary stones. This is contrasted with "silent trade"...

In chapter 2,Brown discusses one of the most ancient forms of trade. He says it is silent trade. First we have been introduced, or reminded, that boundary stones were safe places where neighbours or neighbouring villages would meet. Since war or conflict could arise out of competing tribes the idea of placing stones as a neutral meeting spot is a practical idea. It seems there is some kind of formality or ritual of greeting we might have done at these boundary stones. This is contrasted with "silent trade"...In "silent trade" the parties to the exchange never meet:the seller leaves the goods in some well-known place; the buyer takes the goods and leaves the price. The exchange generally takes place at one of those points which are sacred to hermes-a boundary pint, such as a mountain top,a a river bank, a conspicuous stone, or a road junction. The object so mysteriously acquired is regarded as a gift of a supernatural being who inhabits the place, and who therefore is venerated as a magician and culture hero.

I was triggered by this idea because in the fall, driving on side roads anywhere in North America one is likely to come across a personal farm stand. It is almost always not guarded and produce or goods are kept shaded by a canopy and a note tells the visitor or passerby how much money to leave for so much produce.

(Have read chapers 3 and 4, Homer, Hesiod -- fortunately this is not a long book.)

(Have read chapers 3 and 4, Homer, Hesiod -- fortunately this is not a long book.)Dan, again I must eat my words, since I had said to Candy this group read would be of at most two. And it was really good to read your post and get the broad perspective. I had not heard of Life against death before this thread opened.

I'll explain how all this started, since it is quite interesting.

Candy and I are in a Shakespeare reading group, and have read TWT (The Winter's Tale). It has one foot in the contemporary world, one in ancient Greece. In its Greek setting, it makes use of the myths, Pygmalion (a statue coming to life), Alcestis (a queen returning from the dead) and Autolycus, the thief son of Hermes/Mercury. Autolycus meant nothing to me, but Candy spotted the connection with Hermes, mentioned N.O. Brown's book, and I ordered it second hand. Shortly after there arrived what Americans describe as a "mass market paperback", which means a fragile unbound book on horribly oxidised paper. A sorry specimen, but it will have to do!

One could almost believe Shakespeare had read N.O. Brown. Autolycus is trickster, adopting a series of roles and disguises to fool the peasantry. He is a successful thief -- from sheets off clotheslines to purses. But he also has a useful side, helping prince Florizel with boundary crossing, i.e. eloping to another country. He introduces himself as one who used to be in the prince's service. Later he swaps clothes with the prince, and distracts the peasants who are about to make a report to the King, thereby securing the Prince's escape. His tells us he was "littered under Mercury", an astrological connection rather than a claim of parentage, but we get the point.

All this gets more interesting in the broader context of TWT. Hermes, deceitful and friendly may be contrasted with Apollo, truthful but vengeful. (In the play, disaster follows the denial of Apollo's oracle.) The story is strangely comparable to the Alcestis of Euripes. In Alcestis, Apollo is bondsman (slave, I suppose) to the King, and, being in disguise, is the one practising deceit. Alcestis, the Queen, dies, but is recovered from death by Heracles, who wrestes with death (Hades) and bring Alcestis back to her husband. So Heracles is a robber (Brown makes a robber / thief distinction) helping man, acting one might say as the Trickster. Brown points out that these benevolent thefts are often of things owned by the gods that man is trying to get, fire or immortality. So the serpent in Genesis is an example of the Trickster at work. In TWT the Queen recovered from death is usually rationalised by the reading or viewing audience: she was hidden away, and only pretending to resurrect. But there is nothing in Shakespeare's text to suggest that. Rather there is a sense of mystery, not unlike the sense of mystery that the more thoughtful type of Christian might see in the story of the Resurrection. It is possible therefore to see in TWT an exploration of these very ancient ideas.

I've just finished up chapter 4 too.

I've just finished up chapter 4 too.I love this recollection Martin, well done. It's nice to think about how one idea flows into another and where reading can take us.

I feel very many ideas and connections when I read through this book. For such a small book it has a lot of quick flashes of content and all over the place with words and, as you say, ancient ideas.

For me what begins to happen, is that I start thinking of images. I know that Brown was probably trying to trace the history of economics and as Dan points out, explain how theft and robbery are different and the economic purpose (maybe?) of "crime".

The way I am approaching this book is not too defined. Just going through it and picking out things that catch my eye.

I read this a long time ago and it always influenced my art work and how I read may books. I see association after association.

I think the way Brown thinks has influenced a lot of people since.

I am thinking specifically in contemporary books of Malcolm Gladwell and Leavitt and Dibner. These three have published immensely popular books about economy and "why we live the way we do and do the things we do"....

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freakono...

Candy, I’d like to comment on your including that link to Cultural Materialism—it seems a propos given Brown’s comments in his preface:

Candy, I’d like to comment on your including that link to Cultural Materialism—it seems a propos given Brown’s comments in his preface:“This study of the Greek god Hermes explores the hypothesis that the interrelation of Greek mythology and Greek history is much closer than has generally been recognized...What I have sought to do here is to correlate these changes [in the myth:] with the revolution in economic techniques, social organization, and modes of thought that took place in Athens between the Homeric age and the fifth century B.C.” (v.—the page numbers I’m using are from the Viking edition)

I am reminded of Levi-Strauss’s saying of myth that it is “an imaginary solution to a real contradiction.” The myth comes out of a historical context, and its meaning should be understood in that context. If the myth evolves, does that mean that the situation has changed, or that the “solution” to the situation has changed? I guess Brown is talking about both with the mention of “the revolution in economic techniques, social organization, and modes of thought.”

Before saying anything about the book itself, I wanted to just include a comment on the idea of a myth that evolves, and what that signifies. Although I wanted to say something about modern dress productions of Shakespeare, I think an example of a myth that evolves that is more contemporary, and ubiquitous at the moment, is that of the vampire. How far from the “original core” of the vampire myth is its popular representation in books like Twilight, etc.? And certainly one can see in this case how the changes in the myth are a response to socio-economic factors—in the contemporary moment, the vampire has become, among other things, a way to market to teens. I haven’t read Stephanie Meyers’s books, but I can guess that the themes include teenage sexuality, innocence and experience, and being an outsider. How could the character of the teenage vampire miss in contemporary Western society? But would these themes have been central to the “original core” of the myth?

So to come to Brown, I think one of the points he is making in the first chapter is how “pre-rational” the minds of the “primitive” Greeks were. He does not actually emphasize the point, however, so I wonder whether it was the sort of thing he felt he did not need to prove as he felt that most of his readers would agree with him. There are just a couple of mentions of this, and I had to reread the chapter in order to find them.

Reading the chapter the first time, I thought it was odd to read “Seduction was, throughout Greek civilization, a magic art, employing love-charms, compulsive magic directed at the person desired, and supplicatory rituals invoking the deities of love” (14). This seemed a little too universalizing to me—were there no instances of seduction in which magic was not involved? Could Brown make such a generalizing statement as this?

Later in this chapter, in a discussion of the relation between Hermes the Magician and Hermes the Craftsman Brown comments on the relation between trickery and magic. He says that the word “trick,” “which in Homeric Greek has connotations of magical action, is also used interchangeably with the usual word for ‘technical skill’” (22). In the same passage, he links the words “steal” and “stealthy” with “technical proficiency” (23). At the end of the paragraph he writes that “the aptness of the root [of stealthy, steal:] as applied to technical skill derives from its basic meaning of ‘secret, mysterious action’: Odysseus’ skill with the bow is uncanny” (23, italics Brown’s).

To an onlooker, sure, but would Odysseus himself have considered his ability with the bow magical? The same sort of question might be asked of the seducer who uses words to win over the object of his or her desire.

These passages made more sense to me in the context of other passages in the book:

“A review of Hermes the Trickster shows that his trickery is never represented as a rational device, but as a manifestation of magical power” (11).

“Thus Hermes was magician, and Hermes was trickster. But what is the relation between the two? By and large, the primitive mind makes no distinction between trickery and magic. Modern science would agree, but with this difference: for the scientist the belief in natural causation reduces magic to mere trickery; the primitive, referring the unintelligible to supernatural causes, regards all trickery as magic” (18).

That phrase “all trickery as magic” is an interesting one. Suppose a man were wearing a toupee good enough to fool others into believing it to be real. If he were to show a primitive that the toupee could be removed and put back on his head again, would the primitive see this as magic? Would the primitive not have to resist rational thought actively in order to think that the toupee was a form of magic? Possibly so. The point I want to make is how broadly the words “magic” and “trickery” are employed in Brown’s representation of the primitive mind. If you were to trick the primitive of whom Brown speaks, and then show him how you tricked him, would he still view it as magic? Perhaps, because in Brown’s representation, there does not appear to be a significant distinction between “magic” and “technical skill.”

I've just had the opportunity to read the latest posts (19-22). Candy, you write:

For me Hermes is a magician associated with art-making. His "magic" seems to have to do with the feeling we might get when art moves us. It's invisible and intangible to explain "why". The idea that a god or goddess has magic inside the artist etc and the viewer to explain the potential power of art is very interesting to me.

That's very much the idea I want to get at with regard to Brown's broad use of the term magic. When watching a great athlete, artist, actor, musician, etc. do something that we feel is utterly beyond ourselves, do we not all become pre-rational in a way? Odysseus could give us lessons in the bow, but his skill would still seem to us "uncanny." The same could be said, I suppose, of Tiger Woods, Michael Jordan.

By the way, I noticed some discussion of F is For Fake in one of your other groups. How about Elmyr. A forger, therefore a trickster--and would we say his ability is uncanny? If not, why not. Really great film.

Martin, I think there's the possibility of an academic paper in the connections you mention between TWT and Brown's book on Hermes. The parallels seem to be there--thief versus robber, the employment of Autolycus as a character, the theme of boundary crossing, the reference to Mercury. Wonder if something can be done with Hermes's function as psychopomp and the expiring and resurrecting queen (at the very least, there's something obviously Frazerian about that).

Additional thoughts, coming from thinking about Elmyr: plaigiarism and tricky theft. I was thinking in particular of Kathy Acker, a novelist I like, who frequently takes passages verbatim from well-known novels and uses them in her own work. The titles of two of her novels, for instance, are Great Expectations and Don Quixote.

Additional thoughts, coming from thinking about Elmyr: plaigiarism and tricky theft. I was thinking in particular of Kathy Acker, a novelist I like, who frequently takes passages verbatim from well-known novels and uses them in her own work. The titles of two of her novels, for instance, are Great Expectations and Don Quixote.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathy_Acker

If I'm not mistaken, part of the problem many had with T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land" when it first came out was that it appeared to be a plaigiarized work.

"If you steal from one author it's plagiarism; if you steal from many it's research."

Wilson Mizner

Another artist/plaigiarist I would mention is Sherrie Levine who practices "re-photography"--taking photographs of famous photographs and presenting them as her own.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherrie_...

Other things come to mind--perhaps under the heading of forgery, including doping athletes, lip-syncing singers (Milli Vanilli, anyone?) Or how about the questionable business practices--Ponzi schemes, for example--that brought about the economic troubles on Wall Street so recently?

I suppose the thing is that a line can be drawn as to whether the things I'm mentioning are uncanny or not. If any of these characters I'm mentioning are protected by Hermes, they are probably the ones who never get caught, or, if they get caught, are excused. It's the ones who are uncannily tricky in their forgeries and thefts who get away with it.

Dan, I think that both Marvin harris (Cultural materialism) and Norman O. Brown would have bene peers and probably were aware of each others work. Brown is approaching closely to the way Harris works. Both are concerned with the relationship of social customs (including courtship, trade, agriculture, ritual) being long time directly related to economic benefits to a society. I think Brown differs in that he has a long interest in political choices we could make with knowledge whereas Harris always seemed to be more interested in observing roots of economy and ritual without a political agenda.

Dan, I think that both Marvin harris (Cultural materialism) and Norman O. Brown would have bene peers and probably were aware of each others work. Brown is approaching closely to the way Harris works. Both are concerned with the relationship of social customs (including courtship, trade, agriculture, ritual) being long time directly related to economic benefits to a society. I think Brown differs in that he has a long interest in political choices we could make with knowledge whereas Harris always seemed to be more interested in observing roots of economy and ritual without a political agenda.I'm being firm with Brown here though because I get the sense he also just really find s people interesting.

I think your example of Vampire and their changing purpose in culture is such an excellent parallel to Hermes The Thief. I have read Stephanie Meyers books ( a couple, not all the series, enough for me though) and I was pretty fascinated that she uses the power and magic undead life of Vampires as a metaphor for "born again" and being Christ Consciousness.

Seems quite a strange trip the blood sucker has taken. Quickly the myth likely began with stories structured like the one about Lilith. Then adopted by Christian folklore as a myth to teach lessons on leaving the faith...and

during the 80's and 90's Vampire movies touched on the fears and social challenges of AIDS. Now Meyers has inversed the Myth back to a Christian usage but with the Vampires being "the good Christians".

It's an incredible journey.

Yes! Your example of the toupee is a very good one. I would also include breast implants, and hair extensions, botox, make up, slinky fabrics, stillettoes. Women have long had access to magazines and clothing, family that teaches us about the art of illusion.

It most certainly is magic and we don't need to venture with our toupee example all the way to another country. These magic devices and artistic embellishments work perfectly well on the culture immediately surrounding us. And I would say it is magic.

When we consider a movie liek Avatar which so obviously uses Myth and special effects to produce a stunning sensation fo magic...we see what masters of magic we are today. Magic is not the sole domain of "primitive" or indigenous cultures and religions. A quick visit to a Catholic Church or a Buddhist Temple will reward a visitor with all kinds of illusions and magic too.

Oh. Mon. Dieu.

F For Fake has such resonance for both this discussion on Hermes and for Orson Welles. What a truly magical brilliant movie. We really should try to include a discussion of that movie somewhere here...maybe in tune with Citizen Kane.

Every artist (and I am both a painter and film maker) is woking with a long tradition of being a faker, and a magician. We want to mess with an audiences perspective and emotions and feelings. It is almost completely dependant on how sucessful we are with such experiemntation to making images.

but oh...this whole set of posts here has me so pleased and fired up.

More in a bit...

p.s. Dan, I don't suppose you've run into a friend of mine in London philosophy and literature...John Vanderheide?

p.s. Dan, I don't suppose you've run into a friend of mine in London philosophy and literature...John Vanderheide?

That's a great summary of the vampire myth--I was only thinking back past Bram Stoker to the East European legends--but you take it back all the way to Lilith. You also supply more detail on the modifications to the myth in contemporary times. I'm surprised to know there's a Christian meaning to the myth in Meyers's work.

That's a great summary of the vampire myth--I was only thinking back past Bram Stoker to the East European legends--but you take it back all the way to Lilith. You also supply more detail on the modifications to the myth in contemporary times. I'm surprised to know there's a Christian meaning to the myth in Meyers's work.I would really like to see F is For Fake again. The one time I saw it, it was on the Turner Classic Movies channel. I didn't bother to record it, although I should have.

The whole Orson Welles thing has me thinking of one of the greatest hoaxes of the last century, the radio presentation of The War of the Worlds. And now, when you consider, The *Mercury Theatre*? Is it too perfect?

The name John Vanderheide--no, I don't believe I've heard of him.

Candy: All right, I looked online and I see that John Vanderheide was associated with the Center for Theory and Criticism at U.W.O. I did not meet many students from that program, althought I did have a bit of a connection in that the supervisor of some of my work at U.W.O. was Thomas Carmichael, who at the time was the Acting Director of the Center for Theory and Criticism. It's largely due to his direction that I pay more attention to historicism in the analysis of literature.

Candy: All right, I looked online and I see that John Vanderheide was associated with the Center for Theory and Criticism at U.W.O. I did not meet many students from that program, althought I did have a bit of a connection in that the supervisor of some of my work at U.W.O. was Thomas Carmichael, who at the time was the Acting Director of the Center for Theory and Criticism. It's largely due to his direction that I pay more attention to historicism in the analysis of literature.How do you know Mr. Vanderheide?

Yes, exactly Orson Welles did his radio show which was such a "fake". He also "faked" the life of perhaps Howard Hughes or Hearst for Citizen Kane. It makes complete sense his interest in Clifford Irving (who wrote a fake bio of Hughes) and the art forger Elmyr de Hory.

Yes, exactly Orson Welles did his radio show which was such a "fake". He also "faked" the life of perhaps Howard Hughes or Hearst for Citizen Kane. It makes complete sense his interest in Clifford Irving (who wrote a fake bio of Hughes) and the art forger Elmyr de Hory.I mean really who has the authority to write a bio of somene's life? isn't it open game? Citizen Kane is a fake story about a fake character yet it upset many people and affected Hollywood jobs.

Artists fake landscape and study techniques to trick the eye into believing illusions. Trying to make emotions or images represent "reality" etc.

I know John Vanderheide because we were in an online bookclub for Cormac McCarthy for a long time. We were the only Canandians n said book forum at the time. We've met when I was on road trips in "real life" a number of times. Once he moved to London Ont, he wasn't far away from me in Toronto and we had several visits between our cities over the years.

Wow, chapter 5 is where this book really comes together. I was going to post some excerpts but almost all of it is so good. If I can get some ready to quote here this afternoon I will.

Wow, chapter 5 is where this book really comes together. I was going to post some excerpts but almost all of it is so good. If I can get some ready to quote here this afternoon I will. Martin and Dan, have you got to the section called The Homeric Hymn To Hermes yet?

Some excerpts from chapter 5...

Some excerpts from chapter 5...It is indisputable that myths must originally have had some such simple and direct relation to the behaviour of the myth-makers, and no one will dispute the primitive origin of of the myth-motifs of the trickster and the cattle-raider. But it is also true that myths may be transplanted into an environment different from the one in which they originated and that they can survive, by subtle adaptation, all manner of changes in a culture in which they have once taken root. This truth is ignored by those who regard the Hymn itself as primitive. They tell us that "the idea of a trickster-god is one which appeals to a primitive mind," and forget that the same idea also appeals to minds that are far from primitive, a case in point is the medieval epic Reynard the Fox

Nevermind Reynard the Fox...how about the connection between the arrow images of hermes and the enduring story of Robin Hod. We have seen this story evolve over and over and even this month coming is a new Ridley Scott movie about Robin Hood.

Later Brown begins to articulate a concept that ties in to Citizen kane rather nicely...and F For Fake. And very much part of a independent counter-culture alive and well today. The idea of "sell-out" and greed in corporate business as opposed to creativity...say in the music scene or art scene.

Everyone is familiar with the aristocratic prejudice against retail trade and manual labour, rationalized by Plato into the ethical doctrine that all professionals in which the is profit are vulgar and incompatible with the pursuit of virtue. The prejudice is ultimately derived from the conflict between the traditional patriarchial morality, sustained by the aristocracy, and the new economy of acquisitive individualism-the conflict of Metis and Themis in Hesiod. One of the results of this attitude was to identify trade with cheating, and the pursuit of profit with theft.

As we saw in the preceding chapter, Hesiod regards acquisitive individualism as "theft" and "robbery". Solon uses the same terminology in his indictment of those who pursue wealth without regard to the common weal: "The very citizens, in their folly, are willing to contribute to the destruction of our great city, yielding to the temptation of riches. They do not have the sense to set limits to their superabundance. They grow rich through yeilding to the temptation of unjust practices, and sparing neither sacred nor public property, they go stealing and robbing whenever they can.

Now this section has really got my mind ina twist and I need to sort it out.

I see a couple of things going on. One is the initial surprise I first had when I read this...where I believed that this idea of greed and consumption with material goods originated in a Buddhist principle and history. (which it might) But I was surprised because again, hearing of it's other source from Plato which was such a huge influence on Christian beliefs....on Christian structure of church...then compared to the history and times of industrial revolution and now U.S. economic lifestyles.

I hope I'm clear...as I feel quite foggy. So my surprise is that this notion of property isn't from marx but rather from plato. I mean specifically in the "western" cultures. In Asian religions and cultures this was a fundamental principle to battle with and holds true today.

So not only do we begin to recognize how Myths transport to new cultures and adapt (as in the vampire myth or in the Robin Hood/Hermes myth connections) but the actual economic understanding of community has also changed and adapted.

And then the other strange sensation I have is regarding the DIY and independent art/music/film scene. There has been a forty year (at least) concept probably from Pre-Raphaelites in the 1880's to Hippies in the 1960's and up into today that commerce and making music/art should not be a goal. In fact, there are people within the independent scene who reject anyone who makes huge amounts of fame and money by their art. it is considered "selling out".

The stereotype of the person who measures "selling out" is one of strong values, obsession with "authenticity" and roots and suffering for art. The idea that if one makes it huge and popular their work is no longer respectable!

How would these ethical and high-minded folk feel if they knew their values originated from aristocracy?

This particular sentence stood out to me Everyone is familiar with the aristocratic prejudice against retail trade and manual labour, rationalized by Plato into the ethical doctrine that all professionals in which the is profit are vulgar and incompatible with the pursuit of virtue.

Because it reminded me of "virtue". Even the notion and ideals of virtue have changed over century after century. What Greek ideals of virtue were 3000 years ago have changed to what virtue meant to cultures in 1400's or 1800's and more so now today.

What can we possibly mean by virtue. A book I read around the same time as when I originally read this one was Alistair MacIntyre's epic After Virtue where he analyses and investigates the history of "virtue".

MacIntyre provides a bleak view of the state of modern moral discourse, regarding it as failing to be rational, and failing to admit to being irrational.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/After_Vi...

Many thoughts here and sorry if this post has been too long and too unresolved...

Going to be a long post from me too.

Going to be a long post from me too.I read through the Homeric Hymn section last night, but haven't gotten my comments together on it yet. The following is my comments on Chapters Two-Four.

I like the way ritual is associated with place in Chapter Two. Brown talks about the characteristics of different kinds of places: “the familiar mine” and “the inhospitable not-mine” (37) seems to be the most basic (and pre- or a-rational way) to distinguish between places. It resonates with the Freudian theory that the infant first distinguishes between everything that is him- or herself and everything that is not (of course, I’m thinking of Brown’s later turn to Freud—but I’m also wondering how much of his representation of the thought of the Greek “primitive” is based on a construction of the mental processes of children). Brown also mentions “sacred” places (40) and quotes a passage from Maine in which there is a mention of the Markets as “neutral ground” (39). Using these four types of place, one could put together a semiotic square of the sort A.J. Greimas used in his structural analyses.

Mine -------------------- Not Mine

Sacred --------------------- Neutral

One can then classify the different kinds of exchanges using this square. The exchanges between the “mine” and the “not-mine” as exchanges transacted at boundaries between autonomous families (34); the exchanges between the “mine” and the “sacred” as “gifts of Hermes” (41) and, I think, the “silent” trade would go here too (40-1); the exchanges between the “sacred” and the “neutral” as “the agora on the boundary,” where markets emerged on the edges of religious festivals (40).

I would suppose that the exchanges transacted between the “not-mine” and the “neutral” are those exchanges taking place in the agora that reflect not a religious or ritual, but a mercantile impulse.

In this other book I’m reading, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation, I read this passage by the French woman who owned a bookstore in Paris and who became Sylvia Beach’s life-partner:

“A shop seems to us to be a magic chamber: at that instant when the passer-by crosses the threshold of the door that everyone can open...nothing disguises the look of his face, the tone of his words...and if we know how to observe him at that instant when he is only a stranger, we are able now and forever, to know him in his truth....This immediate and intuitive understanding, this private fixing of the soul, how easy they are in a shop, a place of transition between street and house!”

I thought to quote it because I felt it resonates with the themes of the second chapter—a place of exchange, a “place of transition,” the entry of a stranger.

On the subject of etymology—maybe Brown mentions this later, but I thought I’d mention Mercury comes from the same root (mercis, merx) as the words merchant, merchandise, mercantile.

The long paragraph on pp.42-3 discusses “legitimate appropriation.” There is a mention of “the ritual of Hermes the Giver of Joy at Samos, at which there was general license to steal” (43). One thing this makes me think of is the idea of “free downloading,” where artists are happy to give copies of their work away, as it increases their exposure. Similarly, there are artists who invite other artists to sample their work, to use it in mash-ups, etc. Of course, I am still thinking about my earlier comments on plagiarism, forgery, etc.

For a while, I was also thinking of the concept of “legitimate appropriation” in terms of Brown’s leftist politics, and thinking that perhaps he chose to write about the evolution of the Hermes myth (as opposed to the evolution of the Dionysus myth or the evolution of the Heracles myth) because on some subtextual level Hermes could represent a sort of Marxist hero signifying a utopia in which private property was abolished. I was also thinking that perhaps it could be argued that the primitive Greek Brown discusses might have viewed private property negatively—as a kind of “hot potato” to be passed to someone else—and thus there is all the ritualized exchanging and transacting (as in other cultures one finds the potlatch). However, I’ve changed my mind about that. Brown does not mention the tribal Greek as regarding material goods as possessing some kind of dangerous mana (I see further on in the book that Hesiod was extremely critical of “acquisitive individualism,” but it appears that Hesiod’s position does not have so much to do with material goods themselves as with his dissatisfaction with “the social conditions under which he lived,” 56, footnote 4).

Rather, it seems to me that Brown is interested in what the evolution of a myth says about the evolution of a society, and in this case the effect of economic changes on the society as its organization changed from tribal to monarchic to democratic. And what better way of tracing the economic changes than by analyzing the evolution of the myth of Hermes, the god perhaps most closely connected to economics, exchange, transaction, the merchant class, etc.?

Martin, your quoting the commandment against covetousness makes it hard to argue that the concept of private property in the time of the tribal Greeks had to have been radically different from ours. Indeed, do not the notions of “appropriation,” “permission to steal,” “license to steal,” etc. reinforce the notion of private property? Can there be theft or robbery without private property?

In which case, is not the role of Hermes the Thief, who sanctions theft and stealing, to reinforce the notion of private property? Under his aegis, the rule of private property is subverted, but the function of that subversion is to remind us of the rule. Without private property, the action of stealing has no meaning.

So, far from being a Marxist hero, maybe Hermes is the Ur-Capitalist.

I would really like to quote something from Fredric Jameson’s book Postmodernism here; unfortunately, I can’t find the passage I’m looking for. One of Jameson’s arguments is that in the postmodern moment capitalism has become so universal that it can easily assimilate even that which opposes it—so, for instance, such emblematic anti-capitalist movements like Beat fiction or punk rock or grunge rock are appropriated by the capitalist system and are commodified as goods to market to consumers. I’m suggesting that the early moment of capitalism represented by trickster Hermes could be read as representing something similar—capitalism appropriating to itself that which merely appears to oppose it.

I think the notion of a capitalist, merchant-protecting Hermes takes on more resonance in the context of the time and place in which Brown was writing. It’s the mid-1940’s, he’s a citizen of a country that is on the winning side of a war that has just recently ended; moreover, that country is about to experience a period of affluence unprecedented in its history. Production, distribution and consumption of goods is about to become a big part of Western culture. Along with merchants, there will be a growing class of messengers and heralds (the Madison Avenue people).

I like how the theme of types of places continues through the chapter. As I read Brown’s comments on the common roots of the words for contest (agon) and market (agora), I was thinking of baseball, with its evocative places, and the rituals and characteristics associated with those—the pitcher’s mound, the batter’s box, the foul line, the outfield, the home base.

I also have to comment on the last paragraph of the chapter—really poetic writing. Coming at the end of Brown’s discussion of different kinds of places, the mention of the unfamiliar place names (Mount Pangaeum, Mount Laurium) felt like the beginning of a journey such as one might find in a work of fantastic literature, such as the Lord of the Rings.

Brown’s argument in Chapter Three is very strongly constructed. First, he asserts that myth and ritual are related, and that myth emerges out of ritual:

“The mythology of the trickster is derived from the rituals on the boundary, rituals which originally served the needs of a culture based on autonomous familial collectivities, living in exclusive village communities” (47).

Then, citing Malinowski as an authority, he says that as human behaviours change, the myths associated with those behaviours change too (47)

Then, emphasizing his historicizing approach to the analysis of the functioning of the Hermes myth, Brown states:

“The essential problem of any historical study in the field of Greek religion is to show how religious institutions that were originally integral parts of the pattern of primitive tribal collectivism were adapted during successive phases of historical evolution, to changes in the Greek culture” (48).

It seems to me pretty hard to debate the points Brown is making:

Myth is the product of human behaviour.

As behaviour changes, myth changes.

Therefore, a study of changes in human behaviour must include a study of changes in myth.

At six pages, this was a very short chapter. Hardly anything about Hermes as trickster, thief, magician, or anything like that—just messenger to the gods in the Iliad and Odyssey. I have to wonder, then, whether the Hermes represented in Homer reflects more of an “official” reorganization of the myth, in which Hermes’s subordination in a class system is emphasized, in contrast to a “popular” version of the myth, in which Hermes would continue to represent a character whose function is to subvert, to trick, etc. Again, I’m bringing up Marxist ideas, this time of class struggle. With the emergence of class differentiation in ancient Greece, it’s possible that there was also some class struggle, and different classes had their own versions of Hermes. The one we are familiar with from Homer could represent the Hermes of the dominant order; of the Hermes of the “professional boundary crossers,” however, or the Hermes of the slave class, we know little, as the discourses in which those Hermes are described are not available to us (and may never have been written down).

Yes, this is mostly fantasy. But it’s in response to a radically truncated chapter about a radically truncated—even castrated—Hermes.

From a formal point of view, could the shortness of this chapter be read as signifying a kind of sparagmos—a fragmentation of the book emblematizing a fragmentation of the god reflecting a fragmentation of a society into differentiated classes?

I guess that at this point, though, one can see rational thought emerging in the Greek mind, as they reorganize their myths into a system that resembles their socio-political situation.

The idea of class struggle seems more evident in Chapter Four. Brown writes:

“The champions of the new economy, and of its ethic of acquisitive individualism, were the Third Estate of merchants and craftsmen, who had already crystallized into a distinct social class in the Homeric age, and who were now successfully emancipating themselves from their previously dependent status” (62).

As Brown argues, Hesiod’s Works and Days and Theogony reflect a negative attitude toward this “successful emancipation.” While the Homeric Hermes is a subordinate within a larger hierarchy, the Hermes of Hesiod’s “Iron Age” has too much independence, and is “a satanic character” (55). For Brown, this reflects Hesiod’s critical view of the emerging merchant and craftsman classes.

One line I liked in this chapter: Hesiod “is the first nostalgic reactionary in Western civilization” (63).

Really interestings posts above, especially Dan's last. I was not expecting (and doubt if Candy was) Dan's level of involvement with the text. I feel a bit out of my depth here ... many of the references being lost on me. I've a few points to make though.

Really interestings posts above, especially Dan's last. I was not expecting (and doubt if Candy was) Dan's level of involvement with the text. I feel a bit out of my depth here ... many of the references being lost on me. I've a few points to make though.There are quite a few things Brown leaves unsaid, presumably they were so obvious to him, he did not need to say them. One is that the trading he refers to took place in a world where there was no money -- something quite hard for us to imagine. Another is that it was in the absence of any codified law or police service, to protect individuals against robbery and theft or to enforce contracts. (Even after the invention of money, there was no concept of wage, you either bought the goods or bought the people to make the goods, i.e. acquired slaves. This is elaborated in M.I. Finley's Ancient Economy.) In such a world the boundaries between robbery, theft, trade might well be less distinct that in ours. The decalogue bans "coveting", but this post-dates 700-600BC, the period of interest, and besides, its legal codification suggests there was widespread coveting going on.

Brown stresses a social conflict: the old order of a family-based society versus a new order of specialist craftsmen. The new order needed to survive by trade; the old order saw this (or might have seen it) as something akin to theft.

The question is, can we see things the way that the old order saw them?

The critical quote is,

the aristocratic prejudice against retail trade and manual labour, rationalized by Plato into the ethical doctrine that all professions in which the end is profit are vulgar... page 83

But the old order itself is unlikely to have been aristocratic. Incidentally in England this prejudice is very middle-class, where the professions (medicine, law, teaching ...) often see themselves above the mere money-makers. Hence the derogatory expression "in trade". And middle class in England seems to mean something very different from what it means in the US.

In 600BC you're not sure where you are. The old order might have been small farmers feeling threatened by a new urbanisation, or robber chieftans feeling their old way of life was being displaced by traders who were claiming a similar status.

Similarly with interpreting the Homeric Hymn. Hermes is the "new man" (a baby no less) pushing his way into an established class, represented by Apollo. I will happily grant this interpretation, being unable to imagine a better one! But how is one to take the poet's position? The poem might be saying,

"these new craftsmen are useful after all. They may seem to be no better than the robber barons of old, but their technical mastery makes inventions for us"

--or

"these tradesmen are merely thieves.They exchange their goods with things they've stolen from us in the first place."

It might indeed be a satire. There is also the question, where did the story come from? There are three versions of it (I discover from Graves' Greek Myths), the Homeric Hymn itself, Apollodorus, -- see section 3.10.2 on this page,

http://www.theoi.com/Text/Apollodorus...

and a fragmentary satyr play, "The Trackers" of Sophocles. Apollodorus and Sophocles are centuries later. Apollodorus' account is so similar to the Homeric Hymn it seems to be a direct precis of it. Sophocles throws in Silenus and his satyrs as searchers for the lost cattle (and this finds its way into Graves' retelling), but that was demanded by the dramatic form Sophocles had adopted. I think the author of the Homeric Hymn invented the story. If so, is it therefore myth? Very difficult! G.S. Kirk's book, "Myth ..." goes into "what is myth?" and it has no easy answer. In greek, mythos means story, and I'm not sure one can speak of "the myth of the vampire" etc. independently of a clearly defined narrative about the vampire.

More generally, I think in looking at Greek myths allowance must be made for the fact they have literary origins, and especially origins as poems.

This post is long and dull. I'll write another one about seeing the Homeric Hymn primarily as poem -- sometime over the weekend -- which I hope will be a bit more interesting!

Candy Minx, you mentioned consilience or interdisciplinarity in post 16. At this point, as I think about the different methods Brown is employing in his analysis of the Hermes myth—literary interpretation, etymology and a cultural materialist approach—I see how this book is an example of academic “boundary crossing.” I am supposing that in traditional Classics studies there is not so much emphasis on the social, political and economical conditions out of which this or that myth emerged?

Candy Minx, you mentioned consilience or interdisciplinarity in post 16. At this point, as I think about the different methods Brown is employing in his analysis of the Hermes myth—literary interpretation, etymology and a cultural materialist approach—I see how this book is an example of academic “boundary crossing.” I am supposing that in traditional Classics studies there is not so much emphasis on the social, political and economical conditions out of which this or that myth emerged?I have been seeing the theme of class struggle in some of the earlier chapters, and in Chapter Five it seems to be one of the main topics. I would suppose that for some readers—Classicists—the book is “about” the correct dating of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (the Hymn itself seems as if it would be of particular interest to Classicists more than to the general reader—while many of us have read or at least have some knowledge of The Iliad and The Odyssey, as well as The Works and Days and The Theogony—who doesn’t know the myth of Pandora for instance?—the Homeric Hymn is probably one version of the Hermes myth that doesn’t get read. I certainly have never read it, and as I read Brown’s description of the narrative, I read it the way I would read any story I had never heard before).

For me, though, Brown’s book has been more “about” a cultural materialist and historicist critical method than about a myth. While the subtitle signifies that the book is about the evolution of a myth, for me the book has been about how a number of versions of a myth reflect the emergence of a class in ancient Greece, how that class become more and more closely associated with the hero of that myth, and how the different versions of the myth reflect what was said about that class by other classes, in addition to what the class said about itself. The “narrative” of Brown’s book seems to be about the emergence of the merchant and craftsman class, and the struggle between this and the other (aristocratic, farming) classes.

The myth of the Homeric Hymn itself...the representation of Hermes seems quite different from the Hermes of the first chapter. Both are tricksters, magicians, thieves, etc., but as Brown points out, there is more psychological realism in the Homeric Hymn than in earlier versions:

“The realism of this portrait [...:] is based on observation” (78)

“From the observation of craftsmen at work are derived such vivid touches of psychological portraiture as Hermes’ jouyous laughter, his ‘eureka’ when he gets the idea of the tortoise-shell lyre” (79).

In this context, I want to include a quote from Fredric Jameson. He comments on a passage in Arnold Hauser’s Social History of Art, in which Hauser notes an increased naturalism in the Egyptian art work of the Middle Kingdom (about the time of Ikhnaton) as contrasted with the hieraticism of earlier art. While Hauser says that part of the reason for the changes in methods of representation reflect changes in religious thought, part of the reason is an increased importance of money and commerce and the change this effects in social relations. Jameson writes:

“Herein lies the unorthodox kernel of these orthodox explanations: for it is tacitly assumed that with the emergence of exchange value a new interest in the physical properties of objects comes into being. Their equivalence by way of the money form (which in standard Marxian economics is grasped as the supersession of concrete use and function by an essentially idealistic and abstract ‘fetishism of commodities’) here rather leads to a more realistic interest in the body of the world and in the new and more lively human relationships developed by trade. The merchants and their consumers need to take a keener interest in the sensory nature of their wares as well as in the psychological and characterological traits of their interlocutors; and all this may be supposed to develop new kinds of perceptions, both physical and social—new kinds of seeing, new types of behaviour—and in the long run create the conditions in which more realistic art forms are not only possible but desirable, and encouraged by their new publics.” (“Culture and Finance Capital,” The Cultural Turn, 146)

That is, Jameson argues that once an economy shifts from being dominated by use value (what can I do with this object?) to being dominated by exchange value (what can I get for this object?), people start paying more attention to the details of objects (how is Seller A’s shovel better than Seller B’s shovel?) and to the psychology of other people (how can I do business with this seller/ this customer so as to maximize my profit?). One result of this is increased realism in the representative arts.

Candy Minx, Martin, would either of you be in agreement with me that the myth kind of jumps the shark with its representation of Hermes as having just been born when he steals Apollo’s cattle, invents the lyre, etc.? I suppose that if he wants to be Apollo’s equal, he has to start early, but is the myth improved by the fact that Hermes is a day old? Although Brown does not use the point in this way, for me the fact that Hermes is represented as a baby in the Hymn is another reason for thinking that it is more recent than the Homeric and Hesiodic versions of the myth. Perhaps because for me this is the kind of thinking that gives us precocious child characters on sitcoms. And Little Archie comics. And Muppet Babies.

What I liked better than the representation of Hermes as a baby was the different registers Brown employed to tell the myth. At one point, Hermes is a gangster film tough guy, telling an old man “that if he knew what was good for him he would keep his mouth shut about what he had seen” (70). His “Father I cannot tell a lie” to Zeus (70) is a too-conscious echo of the myth of George Washington and the cherry tree. In terming it an “apologia pro vita sua” (75), Brown employs language to characterize Hermes’s defence of his theft to his mother that we feel Hermes would not himself employ; the effect, for me, is to suggest that Hermes’s defence is not sincere, but an exaggerated parody—as if Hermes felt that his mother was not going to believe he was penitent, but that he would have to act as he were anyway, for the sake of appearances.

Candy Minx, you quote a few passages from Chapter Five representing the attitudes of ancient Greeks who were critical of the impulse to profit. For instance:

Everyone is familiar with the aristocratic prejudice against retail trade and manual labour, rationalized by Plato into the ethical doctrine that all professionals in which the end is profit are vulgar and incompatible with the pursuit of virtue.

I’m not a fan of Plato, and my sense is that he thought a life well-spent was a life of contemplating the Ideal Forms, rather than a life of action (such as labor). However, if I’m not mistaken, he thought that a class of laborers was necessary for a just society. In his Republic, he discusses an idea society made up of an aristocratic class (at the top of which would be the Philosopher-King—guess who Plato was thinking of for that job?), a class of soldiers who would police the society and defend it from enemies (Big Brother is Watching You!), and an “appetitive” class—those who would produce goods on the farms and in factories. So although for Plato manual labor might have been “incompatible with the pursuit of virtue,” his ideal society would require at least a few unvirtuous types for the summum bonum. After all, the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.

On a similar subject, I don’t know about Brown’s line “Benjamin Franklin’s opinion that commerce is generally cheating” (85)—he wrote a book called The Way to Wealth. Come on, his face is on the five dollar bill. Maybe he should have said where Franklin says this.

Candy Minx, you quoted a few passages on politics in art; I’d add this one:

“When the nouveaux riches of the archaic age broke the aristocracy’s monopoly of the arts of cultured leisure, they installed their own god [i.e. Hermes:] as patron of these arts, on a par with Apollo [...:] Hermes symbolized the aspirations of the non-aristocratic classes—and the idealization of the acquisitive philosophy which Solon, Theognis, and so many others denounced” (101).

So Hermes is a patron god for the working class artist. I like how Brown includes acquisitiveness in the latter half of the passage I quoted—one can do business, make money, and still have a creative life.

But, Candy Minx, in connection with your mention of “the DIY and independent art/music/film scene” in post 31, I’d mention that that feeling that creativity and business don’t go together is probably more likely the conventional view. I do not suppose there are many novels, plays, films, in which there is a character who is both a successful businessman and a successful artist? In most of the fictions I’ve read, if there’s a businessman and an artist, the two are usually opposed to one another.

Martin, you make some good points about the problems in Brown's representation of economic behaviour in ancient Greece. As I read the book, I see that most of the footnotes refer to scholarly work on Classical myth--if there are any on the economics of Homeric or pre-Homeric Greece, there probably aren't so many. And yet it seems as if the notion of the emergence of new classes and the changes in economic behaviour related to this are important to Brown's argument. So, as you suggest, he could have supplied some more detail about the economic realities of ancient Greece.

Martin, you make some good points about the problems in Brown's representation of economic behaviour in ancient Greece. As I read the book, I see that most of the footnotes refer to scholarly work on Classical myth--if there are any on the economics of Homeric or pre-Homeric Greece, there probably aren't so many. And yet it seems as if the notion of the emergence of new classes and the changes in economic behaviour related to this are important to Brown's argument. So, as you suggest, he could have supplied some more detail about the economic realities of ancient Greece.But I think this is where one gets into one of the problems of the "soft" sciences (humanities, etc.) Using a text that was written at some remote time in history, one infers that the historic circumstances out of which the text emerged must have been thus and so. Then, taking as proven that the historic circumstances out of which the text emerged must have been thus and so, one infers that that one of the meanings of the text may have been x and y. Then, taking as proven that the meanings of the text may have been x and y, one goes on to make further claims about the historic moment out of which the text emerged.

So it could be asked how much Brown's notion of economic behaviour in Greece is a result of conclusions he has made based on his reading of Greek literature (and how much those conclusions are based on the specific things he wants to prove)

Dan, I loved your excerpt about the bookstore and how it can feel like entering a different kind of place. I know what I feel when I get to certain bookstores...especially when I am excited about picking up a special book and knowing it might be there. It's as if one might be able to be aware of "deciding" to use their imagination.

Dan, I loved your excerpt about the bookstore and how it can feel like entering a different kind of place. I know what I feel when I get to certain bookstores...especially when I am excited about picking up a special book and knowing it might be there. It's as if one might be able to be aware of "deciding" to use their imagination.I don't know if anyone around here is watching the Olympics, but I have been trying to keep up with all the great events. During the opening ceremony....I watched it broadcast in US where I have always only watched it broadcast from Canada. It's a strange sensation to hear the way the newscasters were describing Canada. And then I heard a segment online afrom the Canadian broadcast...and just before the symbolic sections of the opening ceremony...the canadian broadcaster said "this part of the ceremony is where we use our imaginations"

I laughed so hard, it was so funny so geeky and so typically Canadian that we would all decide to suspend out disbelief.

I think that a large part of what is suggested in Brown's book even when he says that intimate and sexual encounters were always based on ritual...he is (too quickly) skipping by the breakdown of ritual and it's connections to behaviour.

Martin has touched on this in his last post too. Brown writes assuming we all know what he is talking about. I believe he wrote specifically for a classical audience and academic audience...so I can forgive him.

Actually, oddly enough...I find a lot of books on Myth tend to take a eap, no background and have a very fast and loose academic style and assumption that readers know what is "going on". It's not a "bad" thing...it seems more reflective that the genral public doesn't read these types of academic essays on Myth or anthropology.

Writers like Harold Bloom, Malcolm Gladwell, Marina Warner try to give backgrounds but their scope is so wide and they come out shooting at the hip...and I would say this book does the same thing. The style is dependent on a rigorous index, appendices and reference notes.