Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Martin Chuzzlewit

Current Group Read

>

Martin Chuzzlewit 1: Chapter 1 - 10

That is good to know about Coutts. I recall her name from biographies, but did not know much about her.

That is good to know about Coutts. I recall her name from biographies, but did not know much about her.

The information you provided as an introduction was great, Plateresca. Funny how I couldn't open it on my iPad but no problem on my laptop. I'm finding more tasks in life that can't be done on an iPad. Glad I have an easily accessible alternative now.

The information you provided as an introduction was great, Plateresca. Funny how I couldn't open it on my iPad but no problem on my laptop. I'm finding more tasks in life that can't be done on an iPad. Glad I have an easily accessible alternative now.Looking forward to starting reading MC shortly.

Thanks for the great introductory material, Plateresca. This is one of Dickens' that I haven't read yet, so I'm excited to read it with the group. What is interesting is that I have another Facebook group and a group on Litsy who are also starting this book on Sept. 1, so I will be killing three birds with one stone!

Thanks for the great introductory material, Plateresca. This is one of Dickens' that I haven't read yet, so I'm excited to read it with the group. What is interesting is that I have another Facebook group and a group on Litsy who are also starting this book on Sept. 1, so I will be killing three birds with one stone!

John, thank you. I think Miss Coutts deserves to be known, but I also had another reason for mentioning her. I think when we read about characters like the Brothers Cheeryble in 'NN', kind and generous people who help others, we tend to attribute a fairy-tale quality to them. But such people did exist (the brothers themselves, of course, were based on real-life prototypes), and, in fact, Charles Dickens himself was one of them (I mean, kind people, not the brothers Cheeryble %)). (And I'm sure such people exist in our days, too). So next time when we meet a charitable character, let's not immediately dismiss this character as unrealistic :)

John, thank you. I think Miss Coutts deserves to be known, but I also had another reason for mentioning her. I think when we read about characters like the Brothers Cheeryble in 'NN', kind and generous people who help others, we tend to attribute a fairy-tale quality to them. But such people did exist (the brothers themselves, of course, were based on real-life prototypes), and, in fact, Charles Dickens himself was one of them (I mean, kind people, not the brothers Cheeryble %)). (And I'm sure such people exist in our days, too). So next time when we meet a charitable character, let's not immediately dismiss this character as unrealistic :) Sue, thank you for persevering in search of knowledge :)

Cindy, that's surely a lot of birds!

And so we begin the first chapter...

Chapter 1

Chapter 1Introductory, concerning the Pedigree of the Chuzzlewit Family

Summary & Notes

[For all other chapters, I will be posting my summaries and notes separately, in the tradition of the group. This chapter, however, is tricky: it is introductory in Fielding's style (as are most chapter titles) and very tongue-in-cheek: basically, we're to assume the opposite of what is being said. It has a number of references which might be obscure to the modern reader, which is why I'll be posting my explanations along with the summary, so it's easier to relate the notes to the text. I will use square brackets to distinguish my comments from my paraphrasing of Dickens's words.

I promise: this is the most difficult chapter in the whole book, the rest will be much easier! :)]

The Chuzzlewit Family 'undoubtedly descended in a direct line from Adam and Eve'.

[Who didn't?]

There was 'a murderer and a vagabond' 'in the oldest family of which we have any record'.

[I.e., Cain].

According to the narrator, most or all of the old and high-ranking families often have violence and vagabondism in their history. And the Chuzzlewits are no exception, they participated in 'divers slaughterous conspiracies and bloody frays'.

'There can be no doubt that at least one Chuzzlewit came over with William the Conqueror.' We know that William the Conqueror granted nobility and land to his supporters (on which the narrator notes, wryly, that it's easy to give away what doesn't belong to you in the first place), but, apparently, this did not happen to the 'illustrious ancestor' of the family in question, so the Chuzzlewits never had any titles or land.

[NB this attack on Dickens from the American newspaper 'New Englander': 'We have not been able to trace his pedigree back far enough to ascertain whether any of his ancestors fought by the side of William the Conqueror'.

But generally, this is understood as a jab at those who worship the aristocracy and the past.]

This is followed by a number of jokes about the Gunpowder Plot and the possible implication of a Chuzzlewit in it.

[Just in case: As we all remember-remember, The Gunpowder Plot happened on the 5th of November, 1605. A group of English Roman Catholics planned to assassinate King James I. Their plot was to blow up the Houses of Parliament with barrels of gunpowder. They were forestalled. One of the main participants of the conspiracy was called Guy Fawkes, so the celebration of the king's escape from assassination has been called Guy Fawkes Night (or Bonfire Night, as at some point, people have started to burn effigies of Guy and other bad guys).]

Maybe the Chuzzlewit who was involved in the plot was, indeed, Guy Fawkes himself?! The narrator assumes a Chuzzlewit might have married a Spanish lady.

[Fawkes was not Spanish, but he did spend some time in Spain.

Dickens wrote this chapter in early November (1842), which is probably why he was thinking about Guy Fawkes.]

The narrator finds further arguments to support this hypothesis: when some Chuzzlewits decided to become coal merchants, they just watched their coal instead of trying to actively sell it.

[The conspirators failed to do anything with their explosives].

Also, there was a female Chuzzlewit who was nicknamed 'The Match Maker'; this might be an indication of her connection to explosives, she probably was the Spanish lady and the mother of 'Chuzzlewit Fawkes'.

[Scholars think this might be an allusion to the Princess Luisa Carlotta of the Two Sicilies:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Princes...

who was desperate to arrange a marriage between her son and Isabella II, Queen of Spain; since she was the niece of King Louis Phillipe of France, such a marriage would have shifted the balance of power in Europe away from England.

On the other hand, this might be an allusion to James I's scheme to marry Prince Charles to the Spanish Infanta.

Either way, it's considered an allusion to mercenary match-making.]

Then, one Chuzzlewit's grandmother used to say about an old lantern that her son used to carry it on the fifth of November. The narrator believes, or pretends to believe, that she must have meant that her forefather, not her son, carried the lantern, and that he was Guy Fawkes himself.

On a side note, the narrator says such free interpretation is common among commentators.

This is followed by another set of jokes and puns, this time, about 'one Diggory Chuzzlewit' and his 'habit of perpetually dining with Duke Humphrey'.

[This means 'to go without dinner'. The phrase dates from the sixteenth century and may have referred to people who used to walk in the old St Paul's while others were eating. It possibly arose from the belief that Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, a son of Henry IV, was buried there.]

Then goes another story about the Chuzzlewits: one of them said that his grandfather was 'The Lord No Zoo'.

[I.e., he said, in reply to a question about his grandfather, 'The Lord knows who!'. Likely an allusion to Defoe's 'The True-Born Englishman': 'And lords, whose parents were, the Lord knows who?'.]

Was one of their ancestors a Chinese Mandarin?

[Apparently, the name sounds vaguely Chinese to the narrator].

No, but maybe the name of the lord was mispronounced. Maybe the Chuzzlewits are illegitimate descendants of a lord, after all.

Then that Diggory, who was 'dining with Duke Humphrey', gave many things 'to [his] uncle'.

[Which means a pawnbroker, — but, again, the narrator misinterprets this to mean that Diggory had a high-ranking uncle whom he courted.

NB: Diggory had 'great expectations' of this uncle. Apparently, Sheridan was the first to use the phrase 'great expectations' to signify the prospects of a large inheritance.]

We understand that Diggory pawned all of his property and even some items that didn't belong to him.

[The 'Golden Balls' are another reference to pawnshops, not to the 'splendid' 'entertainments'.]

Furthermore, 'many Chuzzlewits, both male and female, are proved to demonstration, on the faith of letters written by their own mothers, to have had chiselled noses'.

[First of all, of course, a mother's testimony of the beauty of her child might not be very trustworthy. But the word 'chisel' also means 'to cheat, swindle', so, again, it's a pun. And, again, the narrator supposes that 'chiselling' only happens in 'persons of the very best condition' (which is in line with what was said about old and high-ranking families having Cains in their history.

Also compare Lady Flavella's 'exquisite, but thoughtfully-chiselled nose' in the silver-fork novel Kate reads to Mrs Wittitterly in 'Nicholas Nickleby'.]

So, the Chuzzlewits had 'origin' and 'importance'.

[Or did they?].

Still, they have 'many counterparts and prototypes in the Great World about us'. The chapter is concluded by observations that the family looked like they could have evolved from monkeys, since 'men do play very strange and extraordinary tricks', and also that some of their qualities belonged 'more particularly to swine than to any other class of animals in the creation'. The chapter ends with the words 'some men certainly are remarkable for taking uncommon good care of themselves'...

[Which sets up our expectations for the next chapter!]

---

In preparing these notes, I've used:

'The Function of Chapter I of 'Martin Chuzzlewit' by Cary D. Ser, Dickens Studies Newsletter, Vol. 10, No. 2/3 (June-September 1979), pp. 45-47

Notes to the Penguin Classics edition of 'Martin Chuzzlewit'

Nancy Aycock Metz's 'The Companion to Martin Chuzzlewit'

Unwin Critical Library, 'Martin Chuzzlewit' by Sylvère Monod

I'll say straight away that many critics hated this chapter; Gissing, for example, thought it 'might well have been omitted from later editions, and certainly would never have been missed'.

I'll say straight away that many critics hated this chapter; Gissing, for example, thought it 'might well have been omitted from later editions, and certainly would never have been missed'.What do you think?

Plateresca, you did a wonderful job of explaining Dickens' humor in the first chapter!

Plateresca, you did a wonderful job of explaining Dickens' humor in the first chapter!I wonder if Dickens was trying to appeal to readers who enjoyed the humor in the Pickwick Papers or his sketches when he wrote the first chapter. The humor would have been understood easier back when Dickens was writing it, and his readers would not have had to flip to the back of the book for notes like I did. He might have been trying to capture readers who enjoy his different types of writing by giving them some variety in the three chapters that were published together.

He gives the sense that the Chuzzlewits might be trying to act more high class than they really are, and have had financial difficulties. It doesn't seem like the first chapter is needed for the plot, but this is the first time I'm reading the book.

Hello everyone, looking forward to reading along with the group. I have read the first chapter and am very happy to be back reading another Dickens!

Hello everyone, looking forward to reading along with the group. I have read the first chapter and am very happy to be back reading another Dickens!

I will be starting and completing Chapter One today. The one thing I recall reading somewhere regarding his novels — in very general terms — was that Chuzzlewit was considered the last of his “picaresque novels.” I wanted to know the definition of that and found this:

I will be starting and completing Chapter One today. The one thing I recall reading somewhere regarding his novels — in very general terms — was that Chuzzlewit was considered the last of his “picaresque novels.” I wanted to know the definition of that and found this:A picaresque novel is an episodic tale featuring a low-born, witty protagonist, or picaro, who survives through clever, often unscrupulous, means in a corrupt society. Originating in 16th-century Spain, this genre uses realistic, first-person narratives to satirize social issues and is characterized by a series of loosely connected adventures rather than a tightly structured plot.

Connie, thank you!

Connie, thank you! I think Dickens wanted to introduce the themes of the novel in a humorous and intellectual way. So, this chapter does not advance the plot per se, but it's a kind of a riddle about what's to come later.

Please be careful with those notes at the back of the book, as they do reveal important plot points, sometimes quite causally and unexpectedly.

Hi, Tom! I'm so happy the first chapter left you with the sense that you're content to get back to Dickens :) I actually find this chapter quite entertaining (and, frankly, more entertaining than some of Gissing's writing).

John, thank you for the definition of the picaresque novel. I've actually said a couple of words about the genre in this here post. I think maybe the English picaresque is a bit different from the classic Spanish, rather rough one (think 'Lazarillo de Tormes'); and if we consider 'Nicholas Nickleby' a picaresque, our hero is not low-born and not unscrupulous (not that witty either, I'm afraid). But yes, it's supposed to be a string of adventures and lots of humour. We shall see how much of this applies to 'MC'.

Plateresca First, congratulations for navigating us through the first chapter so well. It must have been exhausting but you have offered us much detail and insight. I confess that I do not enjoy the chapter that much and don’t really find it that humourous, although it is very cleverly done. I also appreciate the bibliography you provided.

Plateresca First, congratulations for navigating us through the first chapter so well. It must have been exhausting but you have offered us much detail and insight. I confess that I do not enjoy the chapter that much and don’t really find it that humourous, although it is very cleverly done. I also appreciate the bibliography you provided.So, on with the novel.

message 63:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Aug 30, 2025 09:28AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Plateresca, thank you so much for this excellent summary-and-commentary-in-one. I honestly do not think it can be bettered 🙂I take my hat off to you!

As you rightly say, we do not usually have this approach, and keep commentary, reaction and research strictly separate from a summary. However this is an exceptional case, and I think your interpretative presentation here is perfect. Hopefully everyone can also see that your hard work obviates the need for looking at endnotes in the book, which is so risky on a first read. Many of these puns, and allusions to historical events and people need explaining to a modern audience - but as you said at the beginning and now remind us, it is unwise to use notes in the various editions unless you know this book already.

Please do take care everyone! Spoilers are slipped in willy-nilly in such notes. You can tell from the detailed research in Plateresca's comprehensive post for chapter 1, that you will not need to consult external notes to follow and understand this novel.

So what do I think to chapter 1? Well Charles Dickens obsessive that I am, I still have to admit that I think this first chapter is a bit of a dud. It feels more like a prologue, and in the later book editions he could no doubt have wittily subtitled it, indicating to his readers that they could happily miss it out.

In my opinion Martin Chuzzlewit has the worst first chapter out of all his novels. It is self-indulgent to a gross degree, and forces the reader to puzzle out references which will have nothing whatsoever to do with the later narrative (except for the final hint, as Plateresca said). So I agree with the majority of critics, that it is largely a flop. Charles Dickens evidently amused himself writing it, but expected far too much from his readers - even the contemporary ones.

Many readers have been put off reading Martin Chuzzlewit by the overblown sarcasm of this beginning. Hopefully none here will be, because Plateresca has explained it all so beautifully, and as she says, it gets MUCH better 🙂

There are one or two occasional dense chapters like this one, which is why I warned about Martin Chuzzlewit needing time. It is not his longest by any means - that is the lively David Copperfield, which we read as a group first of all! But it is his "heftiest", in my view. However, there are far more of the hugely enjoyable chapters, with all Charles Dickens' trademark wit and humour. Those are the picaresque ones John mentioned. There's a lot of irony, and there are ones full of heart, where Charles Dickens expands his purview, and moves away from the 18th century picaresque style.

So hold firm everyone ... you won't want to miss the many delights contained in Martin Chuzzlewit! 😂

As you rightly say, we do not usually have this approach, and keep commentary, reaction and research strictly separate from a summary. However this is an exceptional case, and I think your interpretative presentation here is perfect. Hopefully everyone can also see that your hard work obviates the need for looking at endnotes in the book, which is so risky on a first read. Many of these puns, and allusions to historical events and people need explaining to a modern audience - but as you said at the beginning and now remind us, it is unwise to use notes in the various editions unless you know this book already.

Please do take care everyone! Spoilers are slipped in willy-nilly in such notes. You can tell from the detailed research in Plateresca's comprehensive post for chapter 1, that you will not need to consult external notes to follow and understand this novel.

So what do I think to chapter 1? Well Charles Dickens obsessive that I am, I still have to admit that I think this first chapter is a bit of a dud. It feels more like a prologue, and in the later book editions he could no doubt have wittily subtitled it, indicating to his readers that they could happily miss it out.

In my opinion Martin Chuzzlewit has the worst first chapter out of all his novels. It is self-indulgent to a gross degree, and forces the reader to puzzle out references which will have nothing whatsoever to do with the later narrative (except for the final hint, as Plateresca said). So I agree with the majority of critics, that it is largely a flop. Charles Dickens evidently amused himself writing it, but expected far too much from his readers - even the contemporary ones.

Many readers have been put off reading Martin Chuzzlewit by the overblown sarcasm of this beginning. Hopefully none here will be, because Plateresca has explained it all so beautifully, and as she says, it gets MUCH better 🙂

There are one or two occasional dense chapters like this one, which is why I warned about Martin Chuzzlewit needing time. It is not his longest by any means - that is the lively David Copperfield, which we read as a group first of all! But it is his "heftiest", in my view. However, there are far more of the hugely enjoyable chapters, with all Charles Dickens' trademark wit and humour. Those are the picaresque ones John mentioned. There's a lot of irony, and there are ones full of heart, where Charles Dickens expands his purview, and moves away from the 18th century picaresque style.

So hold firm everyone ... you won't want to miss the many delights contained in Martin Chuzzlewit! 😂

Plateresca wrote: "Chapter 1 Summary & Notes

Plateresca wrote: "Chapter 1 Summary & NotesBut the word 'chisel' also means 'to cheat, swindle', so, again, it's a pun...."

I didn't know that!

I have a question, is Chuzzlewit obviously a made up name to native speakers?

Thank you very much. I read the summary and notes before reading chapter 1, which helped a lot because I referred to them while reading as well! This is my first time with MC.

Thank you very much. I read the summary and notes before reading chapter 1, which helped a lot because I referred to them while reading as well! This is my first time with MC.

Well done, Plateresca! At first I was a little put off by this chapter, but once I got into it I enjoyed it. Your summary and explanation worked perfectly together and filled in the gaps for me.

Well done, Plateresca! At first I was a little put off by this chapter, but once I got into it I enjoyed it. Your summary and explanation worked perfectly together and filled in the gaps for me. I love Gissing, and while it seems he was heavily influenced by Dickens, he is definitely more sober. I tend to get carried off by Dickens' enthusiasm, and that's what worked for me here.

Thank you John for the picaresque definition. Keeping that in mind, this chapter seems fitting. But I am anxious to get on to the story!

I found some of this chapter very humorous, but it felt a bit like a stand-up comedian with only one joke. It seemed Dickens was making the same observation over and over, only using different "examples". I admit to being happy when it ended. If you want something gripping to pull you into a novel, this is not it. Of course, it does not help that the first time around I needed to stop and find the meaning of things. This time, I got most of the references without any consultation. You did a beautiful job of parsing it, Plateresca. I am sure to get much more out of this, this time around.

I found some of this chapter very humorous, but it felt a bit like a stand-up comedian with only one joke. It seemed Dickens was making the same observation over and over, only using different "examples". I admit to being happy when it ended. If you want something gripping to pull you into a novel, this is not it. Of course, it does not help that the first time around I needed to stop and find the meaning of things. This time, I got most of the references without any consultation. You did a beautiful job of parsing it, Plateresca. I am sure to get much more out of this, this time around.

Sara wrote: "I found some of this chapter very humorous, but it felt a bit like a stand-up comedian with only one joke. It seemed Dickens was making the same observation over and over, only using different "exa..."

Sara wrote: "I found some of this chapter very humorous, but it felt a bit like a stand-up comedian with only one joke. It seemed Dickens was making the same observation over and over, only using different "exa..."I got a particularly good chuckle from the optimistic, hopeful misunderstanding of the deathbed reference to "Lord No Zoo" and the insistence that it referred to an unknown and uncatalogued mandarin nabob. I would never have caught that pun without Plateresca's notes.

I appreciate the notes for this chapter, Plateresca. I was struck by the fact that this sounded like a third person narration with Dickens himself having some fun at the expense of the Chuzzlewits. Then I detected an “I” and thought, well, perhaps not. It was not clear to me because I was expecting the narrator to be omniscient because the first four or five paragraphs sounded exactly like that.

I appreciate the notes for this chapter, Plateresca. I was struck by the fact that this sounded like a third person narration with Dickens himself having some fun at the expense of the Chuzzlewits. Then I detected an “I” and thought, well, perhaps not. It was not clear to me because I was expecting the narrator to be omniscient because the first four or five paragraphs sounded exactly like that.

message 70:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Aug 30, 2025 09:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Anna wrote: "is Chuzzlewit obviously a made up name to native speakers?..."

As the (perhaps only?) native Eng-Eng speaker here, I'll answer this. Yes ... but then so many of Charles Dickens's names are his own inventions, that we almost expect it to be! Perhaps it's impossible then to be absolutely sure, but there are no similar genuine surnames.

As a sidenote, I do love all the alternatives he considered before settling on it (which Plateresca listed for us earlier 😂)

As the (perhaps only?) native Eng-Eng speaker here, I'll answer this. Yes ... but then so many of Charles Dickens's names are his own inventions, that we almost expect it to be! Perhaps it's impossible then to be absolutely sure, but there are no similar genuine surnames.

As a sidenote, I do love all the alternatives he considered before settling on it (which Plateresca listed for us earlier 😂)

I enjoyed the first chapter, reading it as a prologue like was mentioned, and don't mind small doses of this style prose, but do hope Dickens reverts to something more easily readable soon.

I enjoyed the first chapter, reading it as a prologue like was mentioned, and don't mind small doses of this style prose, but do hope Dickens reverts to something more easily readable soon. "Dining with Duke Humphrey,'' which I had seen before, also had a common usage meaning. to go hungry or skip a meaning, as in the example:

Person 1 "What did you have dinner?"

Person 2 "I dined with Lord Humphrey."

And the meaning would be that Person 2 went without usually implying unintentionally.

There are several different stories to the origin for the phrase but I like this one, though I have no idea whether it is more true than any of the others.

A popular error found Humphrey a fictitious tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral. The adjoining aisle, called Duke Humphrey’s Walk, was frequented by beggars and needy adventurers. Hence the 16th-century proverb “to dine with Duke Humphrey,” used of those who loitered there dinnerless.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_E...

I also enjoyed this first chapter for its word play. I definitely didn’t get it all until I read the summary and notes just now but found the playfulness of it exciting as what seems a rather baroque introduction to this family and character. It made me interested to know where Martin falls on this family tree. Thanks Plateresca for all the information that fills out all the allusions.

I also enjoyed this first chapter for its word play. I definitely didn’t get it all until I read the summary and notes just now but found the playfulness of it exciting as what seems a rather baroque introduction to this family and character. It made me interested to know where Martin falls on this family tree. Thanks Plateresca for all the information that fills out all the allusions.

Plateresca wrote: "Sam, Is this what you'll be focusing on during this read, on whether you perceive a change in Dickens's writing? (I know you often choose a particular focus)...."

Plateresca wrote: "Sam, Is this what you'll be focusing on during this read, on whether you perceive a change in Dickens's writing? (I know you often choose a particular focus)...."Well, mostly I will be following your lead especially when it comes to my contributions as I think the enjoyment of our discussions might suffer if there are too many random topics. And I will also be looking for examples where Dickens' writing influenced film techniques.

But aside from considering structure, I plan to focus on Dickens'

examples of compassion and empathy but with specific attention to how Dickens conveys and promotes the value of compassion and empathy by displaying the consequences of their lack in the villains of the book if there happens to be any good examples. Dickens by this time had built quite a catalog of villains whose behavior had surely shocked the readers and much of it was attributable to lack of compassion, empathy, charity and otherwise similar goodnesses and instead they placed their own selfish interests at the forefront of their thoughts. So I will be looking to see if there is a comparable villain or two that continues that in Martin Chuzzlewit. I think it might make an interesting study to compare how that lack of care for others exhibited by the villains may have influenced and deterred future readers from adopting a self-centered focus. It may be farfetched and I don't think Dickens was the only source but I think it interesting to think how Dickens directly and/or indirectly from others adapting and copying him might have had a moral effect on generations of Western readers. Negative examples can have a wonderful deterring effect. I cannot imagine too many people wanting to consider themselves or be considered by others as a fit member of the Squeers family.

Sam, your post provides food for thought, not just concerning Dickens. How much are we affected by the actions and ideas put forth by the characters in works of fiction?

Sam, your post provides food for thought, not just concerning Dickens. How much are we affected by the actions and ideas put forth by the characters in works of fiction?On another note, I enjoyed the first chapter even though I found it hard to follow. I assumed Dickens was poking fun at people who place too much importance on their ancestry. I have not read MC before, so I do not know if this is a theme in the book. But it does come out in some characters in his other novels, so it must be something he had an opinion on.

Peter, thank you, and I also often find the bibliography part to be the best part of an article :)

Peter, thank you, and I also often find the bibliography part to be the best part of an article :) Having read some critique, I know that the more somebody tries to defend this chapter, the more this is seen as an argument for the chapter being weak, seeing as it stands in need of defence.

So I'll say this, rather: if you didn't like this chapter, the good news is, it's the only one of the kind in the book :)

Jean, I honestly tried to separate the paraphrase from the comments here, and this looked like a lot of text. Granted, this still looks like a lot of text %)

Now, should Dickens have left this chapter out of later editions (which was the way Gissing felt)? I've been thinking about that, and, being the giddy person that I am ;), I am quickly divertend into thinking about the way Dickens used to adamantly defend what he did (I'm thinking of the way many critics regretted his insistence on the reality of spontaneous combustion, among other things). So I'm sure of one thing: The Inimitable would have thought of arguments in defence of this chapter, we may be sure of that :)

Plateresca's thoughts on the picaresque, absolutely skippable

Plateresca's thoughts on the picaresque, absolutely skippableThe genre of la novela picaresca appeared in the 16th century in Spain, and both 'Don Quijote de la Mancha' and 'Lazarillo de Tormes' can be viewed in the vein of this tendency, although their main characters are very different.

The Spanish pícaro is often not a nice gentleman; he* is often hungry, dirty, and vulgar. He 'gets knocked down, but he gets up again'. But he gets knocked down in various places and by various other characters, so we get the [sad] picture of the whole [sad] society.

But in a fun way %) It's social satire.

*It is most often a he, but I think of Becky Sharp as quite a pícaro. (Or, say, Lady Susan).

If we treat the pícaro and the picaresque not as a historical genre, but as a general type, think Han Solo, or 'The Golden Ass'.

So in the British picaresque, there is probably a bit less hunger, less violence.

What John said about the lack of structure is quite true: it's a sequence of adventures, not a plot-driven novel.

So, in a way, 'The Pickwick Papers' is a picaresque; the protagonist is supposed to be one of the noblest types in all literature, so, not a pícaro at all, but the structure of the novel, or its absence, is picaresque enough.

And is 'Martin Chuzzlewit' a picaresque or not? This is an interesting question, but it's a bit too early to attempt to answer it :)

Anna, yes, Chuzzlewit is obviously a weird name, and there will be more %)

Anna, yes, Chuzzlewit is obviously a weird name, and there will be more %)Jodi, thank you! Again, I think that none of the other chapters will really need this amount of explaining.

Kathleen of roses, I know what you mean about Gissing's 'soberness' :) And I'm sure he was very much influenced by Dickens's writing!

I wonder if Dickens realized we'd be reading this so many years later, when some of the people he alludes to mean much less to us than the name of 'Charles Dickens'!

And we'll get to the actual plot tomorrow, for sure :)

Sara, thank you for your perseverance :) Actually, I agree, this does feel somewhat like a stand-up act where you laugh just because the joke is repeated so many times. Maybe Forster should have just let him keep the 'yourselves the actors...' thing ;)

Paul, thank you, and I agree, the 'Lord No Zoo' is one of the funniest things in this chapter (although I like the 'uncle' part, too :)).

Well I was thinking as I read Ch 1 that I was going to need to read it again because so much just seemed so over the top. I have to agree with most here who were happy to be finished. I did not reread it because of Plataresca’s fabulous interpretation. Thank you for that. I look forward to what’s to come.

Well I was thinking as I read Ch 1 that I was going to need to read it again because so much just seemed so over the top. I have to agree with most here who were happy to be finished. I did not reread it because of Plataresca’s fabulous interpretation. Thank you for that. I look forward to what’s to come.

What John is talking about is very well-noted! Indeed, we suppose the narrator to be omniscient, or else how would he know all of this, right? But on the other hand, he believes or pretends to believe some things about the Chuzzlewits which we feel just cannot be true. So, what's going on here? I suggest we get back to this question when we finish the first instalment, and then maybe a couple of times throughout the novel ;)

What John is talking about is very well-noted! Indeed, we suppose the narrator to be omniscient, or else how would he know all of this, right? But on the other hand, he believes or pretends to believe some things about the Chuzzlewits which we feel just cannot be true. So, what's going on here? I suggest we get back to this question when we finish the first instalment, and then maybe a couple of times throughout the novel ;)Sue, this is exactly what I thought when reading this chapter: Dickens was obviously enjoying himself :) I think this is maybe what I enjoy most about his writing, his freedom and crazy self-confidence :)

Sam, I'm very looking forward to your 'cinematic' comments! I remember how we discussed the 'camera angles' in one of Dickens's Christmas stories. In 'MC', I know there are at least a couple of very 'cinematic' chapters.

And oh, what you're saying about villains is very pertinent to this book, as we shall all soon see.

Katy, this is well-noted: provenance, or its absence, was really important to Dickens. Some critics said this was because he was sensitive on the subject of his own family; maybe, but then, he still believed people could be good or bad irrespective of their ancestors, and who can argue with that?

Maybe we're also invited to think about how our ancestors, our families and family traditions influence who and what we become...

Lori, thank you. I think Dickens being over the top is just normal Dickens :), but I hope his future 'over the top' will be more enjoyable :)

Katy wrote: "On another note, I enjoyed the first chapter even though I found it hard to follow. I assumed Dickens was poking fun at people who place too much importance on their ancestry. "

Katy wrote: "On another note, I enjoyed the first chapter even though I found it hard to follow. I assumed Dickens was poking fun at people who place too much importance on their ancestry. "In big, bold capital letters, ABSOLUTELY! I 100% AGREE.

This first chapter also had a “tone” that seemed like something I recall from the opening of American Notes: 4/5ths amused and 1/5 bemused. It seemed like he was having fun with both the reader and the Chuzzlewits.

This first chapter also had a “tone” that seemed like something I recall from the opening of American Notes: 4/5ths amused and 1/5 bemused. It seemed like he was having fun with both the reader and the Chuzzlewits.I also find it remarkable that in this chapter alone we get a mention of Adam and Eve — and Darwinism.

My first chance to jump in here! I haven't ever read MC nor did I read the American Notes... I'm glad to read that it won't matter that I hadn't. It also clears up why my Wordsworth Classics edition has a picture of the American Flag on the cover!! I was scratching my head over that.

My first chance to jump in here! I haven't ever read MC nor did I read the American Notes... I'm glad to read that it won't matter that I hadn't. It also clears up why my Wordsworth Classics edition has a picture of the American Flag on the cover!! I was scratching my head over that.As ever, I appreciate all the explanations and notes. I started laughing in Chap 1. from the moment he wrote that the Chuzzlewits were descended from Adam and Eve. I thought the whole chapter was pretty tongue-in-cheek, although overly drawn out in the sarcastic allusions. It almost made me think of the interminable recitations of genealogy found in the Bible, but funnier, of course.

Chris wrote: "I thought the whole chapter was pretty tongue-in-cheek, although overly drawn out in the sarcastic allusions."

Chris wrote: "I thought the whole chapter was pretty tongue-in-cheek, although overly drawn out in the sarcastic allusions."Dickens and his contemporaries were certainly famous for their approach to writing. They were never satisfied with even the most descriptive single word if the heavens moved them to craft a paragraph (or a page or two). I'll take the liberty of quoting myself from my review of Thomas Hardy's RETURN OF THE NATIVE:

"But Hardy, shoulder to shoulder in solidarity with his like-minded Victorian colleagues such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Gissing and the Brontë sisters, was never satisfied with mere tight-fisted single sentences when lush, mellifluous (or perhaps even lugubrious) entire chapters (earning income by the word, of course) would serve!"

John, yes, Dickens was obviously having fun :)

John, yes, Dickens was obviously having fun :) Re: Evolution, cf.:

'The reference to Monboddo here, though facetious, helps to pull into focus the novel's serious preoccupation with "human nature" <...>'. (Nancy Aycock Metz).

Chris, welcome to the discussion! I agree, 'tongue-in-cheek' describes this chapter perfectly! I'm glad you were able to enjoy it :)

Paul, it's a good idea to observe Dickens's writing style. In this book, there are, for instance, two famous paragraphs where a single word is repeated multiple times to create a certain effect. Dickens often used two synonyms in a row for emphasis. But generally, I'd say it's not as simple as just putting in more words where fewer words would have done. I think John Mullan has some interesting research precisely on this topic, but we'll be collecting our own observations along the way, too :)

(I know you all know this and that this was a joke, but still, just in case, an article about the popular misconception of 'paid by the word':

https://dickens.ucsc.edu/resources/fa...)

Thank you for being patient with this chapter, and for all of your comments! You've been quite perspicacious in unravelling this riddle.

Thank you for being patient with this chapter, and for all of your comments! You've been quite perspicacious in unravelling this riddle.I hope I haven't missed anything, but if I have, please don't be shy to draw my attention to your comments. And you're all welcome to add more thoughts about this first chapter!

Meanwhile, we move on to the next one...

Chapter 2

Chapter 2Wherein certain Persons are presented to the Reader, with whom he may, if he please, become better acquainted

Summary

This chapter begins with a description of an evening in late autumn in a little Wiltshire village near Salisbury. The scenery is briefly lit by the 'declining' sun, and everything looks nice and shiny for a moment; then the sun goes down, and everything looks cold and dark again. The village forge and a tavern called 'The Blue Dragon' are mentioned.

The 'angry' wind is pursuing the 'scared' leaves', and it so happens that while a Mr Pecksniff is entering his front-door, the wind blows it shut and blows out the candle of Miss Pecksniff, who is on the other side of the door. Mr Pecksniff falls down the stairs and hurts his head, while Miss Pecksniff imagines the door was open and shut by some child and keeps threatening this imaginary offender with jail... Until she hears Mr Pecksniff sneeze and recognises him:

'That voice!' cried Miss Pecksniff, 'my parent!'

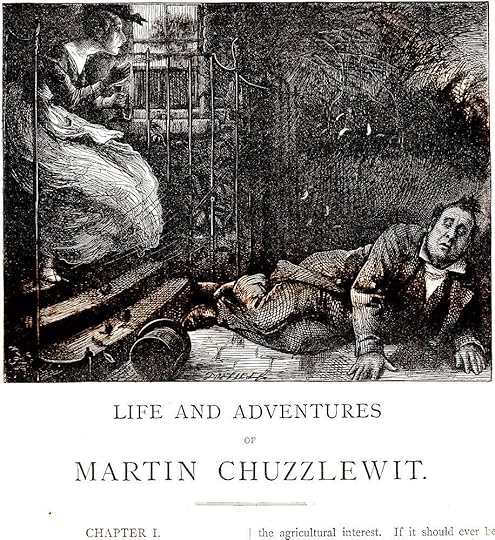

Fred Barnard, Uncaptioned illustration to begin Chapter One, page 1

from the Victorian Web, image scanned by Philip V. Allingham

Her sister comes to her aid, and together they drag Mr Pecksniff inside. They are worried about him, but relieved when he assures them he's feeling better.

The youngest Miss Pecksniff sits upon a low stool at her father's feet, because of, as the narrator explains, her 'playfulness, and wildness, and kittenish buoyancy'. She's also called 'arch' and 'artless'. Her name is Mercy, while her sister's name is Charity. Charity is presumably quite unlike Mercy, and more serious.

Mr Pecksniff is repeatedly called by the narrator 'a moral man', although '[s]ome people likened him to a direction-post, which is always telling the way to a place, and never goes there <...>'. The plate upon his door says he's an architect and land surveyor; but the narrator tells us that he never designed or built anything. Still, he has pupils: 'His genius lay in ensnaring parents and guardians, and pocketing premiums'. So when he is paid to educate a young man as an architect, he collects the money, gives the young man some more or less feasible architectural drawing assignments, and leaves him to himself.

Mr Pecksniff proclaims that even 'cream, sugar, tea, toast, ham...' — and eggs, as Charity adds, — 'have their moral', that being that everything is transitory, and then proceeds to announce that he is to have another pupil. Merry (short for Mercy) wonders if this young man is handsome, and Cherry (Charity) asks if the premium is good. According to Mr Pecksniff, the new pupil is good-looking, but, surprisingly for his daughters, Pecksniff does not expect any immediate premium.

The term of another student of Mr Pecksniff's ended yesterday. His name is John Westlock. Mr Pecksniff expected him to have left, but it turns out he has not. He had drinks with a Mr Pinch the night before, and Mr Pecksniff seems to be hurt by this.

Mr Pinch soon appears; he is a bit awkward and clumsy and looks prematurely aged. Apparently, Mr Pecksniff and his (now former) pupil John Westlock have had 'many little differences', but as John is leaving now, he wishes to say goodbye in a friendly manner; Mr Pinch tries to act as an intermediary.

Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters, by Phiz

from the Victorian Web, image scanned by Philip V. Allingham

Mr Pecksniff assures everybody that he bears John no ill will, but then refuses to shake hands with him. At this, John is indignant: according to him, his relatives have been ripped off by Pecksniff, and it's not up to the latter to speak about presumed 'wrongs' he suffered from John. Pecksniff pronounces that money 'is the root of all evil'. He and his daughters seem hurt by the scene, so John and Tom Pinch go away, carrying the box with John's possessions to the mail coach.

Tom Pinch is upset by what has just happened, while John is optimistic. John does not believe that Pecksniff was really upset and/or suffering. In a tongue-in-cheek manner, he enumerates the reasons Tom Pinch has for being grateful to Pecksniff, and we learn that Tom's grandmother was a housekeeper, and worked hard to save some money; she managed to provide Tom with education, and hoped he would become a gentleman under Pecksniff's guidance. Pecksniff accepted Tom as a pupil presumably for less than was due to him, and now keeps him as his assistant. According to John, this is because Tom is a nice person, he's intelligent, and he even plays the organ at the church, while Pecksniff turns all of this to his advantage, pretending Tom owes his talents to himself. Tom does not believe a word of it.

The mail coach arrives and carries away John Westock. Tom is sad to lose his friend; he thinks him a 'fine lad' with only one drawback: that of being unjust to Pecksniff.

Notes

NotesArchitect, based on notes in 'The Companion to Martin Chuzzlewit' by Nancy Aycock Metz

'During the period the novel was written, architects generally entered the profession from one of two routes: those trained specifically for the vocation — through 'pupillage', reading and foreign travel — enjoyed a higher status than those who entered through the building trades and learnt their skills in the workshop or through the study of builders' pattern-books. But anyone could call himself an architect because the procedure for granting credentials was informal and unregulated (the first common examination in architecture did not take place until 1862, and it was strictly voluntary).'

'Despite the renewed interest in architecture during the 1830s and 1840s, the reputation of the professional architect plummeted. A period of brisk and largely unregulated building invited unscrupulous practice, and the frequently overlapping roles of surveyor, contractor, builder and designer made it all too easy for the dishonest to manipulate figures and cheat unwary clients. The general standard of work was shoddy and derivative, if not frequently fraudulent, and it was received with scepticism by a disillusioned public.'

'Independent surveyors were often employed to prepare bills of quantities from the architect's designs, particularizing the costs of materials and labour as a check against excess expenditure. Any architect who performed this service for builders brought himself into conflict with independent surveyors. Partly for this reason, and partly because 'measurement' was seen as a trade rather than an art, surveyors were excluded from the recently formed Institute of British architects.'

'The apprenticeship system was increasingly the accepted avenue into professional practice in the early decades of the nineteenth century.;

'Though there were many distinguished architects who provided a genuine education for their charges, the pupillage system was particularly open to abuse by the unscrupulous.'

---

It would be no description of Mr Pecksniff’s gentleness of manner to adopt the common parlance, and say that he looked at this moment as if butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth. He rather looked as if any quantity of butter might have been made out of him, by churning the milk of human kindness, as it spouted upwards from his heart.'

John Mullan in 'The Artful Dickens' admires how Dickens creatively combines two chilchés here: 'butter would not melt in his (or her) mouth' and 'the milk of human kindness': 'Out of these commonplaces something truly fantastic <...> is conjured.'

So now we know who's the person playing the organ on the frontispiece :)

So now we know who's the person playing the organ on the frontispiece :)I will say straight away that I really like this chapter, for a number of reasons. What are your impressions of it?

Hi all.

Hi all.I missed the part of Pecksniff falling and needing straightening. I always cannot capture everything in most Dickensian chapters.

The characters introduced are very quickly sketched so that one is drawn to them or repelled by them. This is very quick work by Dickens and the chapter as a result seems shorter than it was.

Yesterday I listened to chapters one and two. One was great in audio and I loved the tone and the satire. The content in chapter two did not work as well in audio. At about midpoint I realized that I was not paying enough attention to the story. I will be reading it today. My intent is to use both audio and print as time and content allow. I’d picked up the audio some years ago.

Yesterday I listened to chapters one and two. One was great in audio and I loved the tone and the satire. The content in chapter two did not work as well in audio. At about midpoint I realized that I was not paying enough attention to the story. I will be reading it today. My intent is to use both audio and print as time and content allow. I’d picked up the audio some years ago.

I thoroughly enjoyed Chapter 1. I'm sure Dickens' British audience would have thoroughly enjoyed it as well, as they would have fully understood the references and the idioms. Without your help, Plataresca, it would definitely have been a challenge to appreciate it as much as I did. Thank you for a great summary and commentary.

I thoroughly enjoyed Chapter 1. I'm sure Dickens' British audience would have thoroughly enjoyed it as well, as they would have fully understood the references and the idioms. Without your help, Plataresca, it would definitely have been a challenge to appreciate it as much as I did. Thank you for a great summary and commentary.I love the tone it set for what readers could expect, and for me personally, I'm ready for this lighter side of Dickens. I love his sarcasm and dry wit! Looking forward to the next chapters!

@ Bionic Jean & Plataresca, Thanks for letting me know, I only realised Chuzzlewit was made-up name after reading message #35.

@ Bionic Jean & Plataresca, Thanks for letting me know, I only realised Chuzzlewit was made-up name after reading message #35. I really like Barnard's illustration, I'd never seen it before.

message 94:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Aug 31, 2025 08:33AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Ah, now this more like it! A wonderful chapter (2) to introduce us to the Pecksniff household.

It has been said that the title of a work can be a direction on how to read it. I'm not sure that is true of the original long title of Martin Chuzzlewit, which is informative but confusingly conflates two Martins and three generations 🙄:

“The

Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

His relatives, friends, and enemies.

Comprising all

His Wills and His Ways,

With an Historical record of what he did

and what he didn't;

Shewing moreover who inherited the Family Plate,

who came in for the Silver spoons,

and who for the Wooden Ladles.

The whole forming a complete key

to the House of Chuzzlewit.”

However, now we see Charles Dickens's genius in preparing the ground. 🙂 I still would have preferred the first chapter to be presented as an an optional prologue, (offhand, I don't think I ever actually agree with George Gissing, Plateresca 😆) but now we can see how the first chapter helped us to set our reading radars, as it were, to sarcasm and irony.

(**MOD'S NOTE - Hopefully it's not needed, but just to add a note to new members and a reminder to us all:

Although we appreciate sarcasm very much in the works of Charles Dickens, and discussing this, the use of sarcasm in the group is discouraged: see rule 3**).

We see comic buffoonery too, as a pompous fellow, Seth Pecksniff is presented instantly as a ludicrous figure of fun. The expression "Pride goes before a fall" is so apt here, that Charles Dickens has chosen to represent it literally to us. What a treat!

It has been said that the title of a work can be a direction on how to read it. I'm not sure that is true of the original long title of Martin Chuzzlewit, which is informative but confusingly conflates two Martins and three generations 🙄:

“The

Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

His relatives, friends, and enemies.

Comprising all

His Wills and His Ways,

With an Historical record of what he did

and what he didn't;

Shewing moreover who inherited the Family Plate,

who came in for the Silver spoons,

and who for the Wooden Ladles.

The whole forming a complete key

to the House of Chuzzlewit.”

However, now we see Charles Dickens's genius in preparing the ground. 🙂 I still would have preferred the first chapter to be presented as an an optional prologue, (offhand, I don't think I ever actually agree with George Gissing, Plateresca 😆) but now we can see how the first chapter helped us to set our reading radars, as it were, to sarcasm and irony.

(**MOD'S NOTE - Hopefully it's not needed, but just to add a note to new members and a reminder to us all:

Although we appreciate sarcasm very much in the works of Charles Dickens, and discussing this, the use of sarcasm in the group is discouraged: see rule 3**).

We see comic buffoonery too, as a pompous fellow, Seth Pecksniff is presented instantly as a ludicrous figure of fun. The expression "Pride goes before a fall" is so apt here, that Charles Dickens has chosen to represent it literally to us. What a treat!

message 95:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Aug 31, 2025 08:30AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

His mentor and biographer John Forster tells us that Seth Pecksniff was based on a real person,

S.C. Hall

, (1800-1889) whom Charles Dickens regarded as a hypocrite and a snob. Samuel Carter Hall was an Irish-born Victorian journalist who edited “The Art Journal” and was widely satirised at the time - but Plateresca may be intending to tell you more ... So I will just comment on how ironic it is that S.C. Hall's name is largely forgotten, but the fictional character invented by Charles Dickens has given his name to an adjective with widespread use:

"Pecksniffian"

! Most dictionaries define this as "affecting benevolence or high moral principles".

Like Plateresca, I find there are so many things I love about this chapter but I'll stop there. What a family - all three carefully delineated so we feel we know them already - as we do Tom Pinch. But what of the disgruntled John Westlock? This chapter leaves us with intriguing questions too.

Plateresca thank you so much for your superb summary - and also the interesting facts about the status of "architect" at the time, which is very telling 🙄Thanks too for including one of Fred Barnard's later illustrations, as well as the originals by Hablot Knight Browne. I do like this illustrator and enjoy the contrast with Phiz's caricatured style.

Like Plateresca, I find there are so many things I love about this chapter but I'll stop there. What a family - all three carefully delineated so we feel we know them already - as we do Tom Pinch. But what of the disgruntled John Westlock? This chapter leaves us with intriguing questions too.

Plateresca thank you so much for your superb summary - and also the interesting facts about the status of "architect" at the time, which is very telling 🙄Thanks too for including one of Fred Barnard's later illustrations, as well as the originals by Hablot Knight Browne. I do like this illustrator and enjoy the contrast with Phiz's caricatured style.

It's good to see you back Luffy!

And Jodi, would you like to introduce yourself LINK HERE, so that we can all get to know you a little? Thanks! 🙂

And Jodi, would you like to introduce yourself LINK HERE, so that we can all get to know you a little? Thanks! 🙂

Plateresca wrote: "So now we know who's the person playing the organ on the frontispiece :)

Plateresca wrote: "So now we know who's the person playing the organ on the frontispiece :)I will say straight away that I really like this chapter, for a number of reasons. What are your impressions of it?"

Plateresca Thank you for the detailed explanation of various routes one could take to become an architect. Still, countless structures still stand, are beautiful in their execution, and very sound. Alas, if only the same could be said of many of our modern equivalents. Also, yes, the ‘Victorian Web’ an outstanding resource. Thanks for referencing it for us all.

After the first chapter it was comforting to settle into Dickens’s enjoyably lengthly first paragraphs of Chapter 2. Such wonderful phrasing and pace, and I enjoyed how Dickens slipped us into the later windy conditions.

As for Pecksniff … does he have a sincere bone in his body? I think not! Dickens’s description of him is so subtly tinged with sarcasm and condescending phrasing. Pecksniff’s self-love is only outdone by his self-deception of the true nature of his character.

Tom Pinch makes his first appearance and I look forward to see how his self-deception concerning Pecksniff is developed. Something tells me John Westlock may have departed for now, but he will return.

Browne’s illustration was interesting in composition. Pecksniff and both his daughters have their backs to Pinch. A clear reinforcement of Dickens’s initial character description of the Pecksniff family.

Luffy, I agree, this is a dynamic chapter, with scenes flowing one into another.

Luffy, I agree, this is a dynamic chapter, with scenes flowing one into another. And we've mentioned the cinematic quality of Dickens's writing earlier, remember? I think it's very interesting how what we might call our imaginary camera circles the village, focuses on the figure of Mr Pecksniff, then there's this incident with the door, and then we go in with some of the characters, and then we go out with some others...

Kathleen, this is interesting; I would have thought that the second chapter with its dialogues would translate to an audio version better than the philocophical//satyrical first chapter; but I guess the atmospheric descriptions at the beginning of Chapter 2 are easier to imagine when reading.

Jodi must be referring to my picaresque ramblings :))

Shirley, I'm so happy you enjoyed the first chapter! I honestly think it has its funny moments. Thank you for your openness and enthusiasm :)

Anna, I agree, Barnard's illustration is very atmospheric, dark and moody, but also appropriately ironic.

Jean, I actually enjoy the character of Mr Pecksniff very much at this point :)

I am aware that he is supposed to have been based largely on S. C. Hall, although some scholars (e.g., cf. "Politics, Class, and 'Martin Chuzzlewit'" by Morris Golden; and also Metz) also name Robert Peel, who became Prime Minister in 1841, as one of the influences.

The thing is, when I was reading about Hall, I felt that maybe drawing a straight line between him and Mr Pecksniff was a bit too harsh on Hall. There are, after all, things that Pecksniff does that Hall never did.

I guess, since we're already labelling poor Mr Pecksniff, I can safely mention Molière's Tartuffe as his closest literary prototype.

If you'd like me to elaborate on the similarities and differences between Pecksniff and Peel and Hall, please remind me to do so at the end of my shift here :)

And, speaking of illustrations, note the art in Mr Pecksniff's living room! ;)

Peter, I'm glad you enjoyed this chapter right from the start!

I personally loved the description of the wind!

[Well, if I say 'I personally', I might as well go on to say that I loved the description of the village forge, too, and of the romantic dragon...].

But, you know, some critics have found fault with this rustic description, and some others refused to take it at face value.

I have many thoughts re: what you say about all of the characters you mention, which I'm keeping to myself just for now, but imagine me making sundry conspiratory nods :)

Again, speaking on a personal level, I love the irony of this:

Again, speaking on a personal level, I love the irony of this:‘And eggs,’ suggested Charity in a low voice.'

Now, why is this so funny? It's partly the contrast with 'the worldly goods', partly that she says this in a low voice (is she begrudging her father the eggs?), and partly, I guess, because she's called Charity... But the long and short of it, it's hilarious, and I can just imagine Charles Dickens chuckling at this scene.

Also, I guess he's really good at depicting domesticity, even if it's the domesticity of the characters he ridicules.

On the other hand, I find the story of Tom's grandmother with her 'hard savings' very poignant...

Books mentioned in this topic

Martin Chuzzlewit (other topics)Martin Chuzzlewit (other topics)

Martin Chuzzlewit (other topics)

Dickens and Phiz (other topics)

The Turn of the Screw (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Fred Barnard (other topics)

Hablot Knight Browne (other topics)

Robert William Buss (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...

I have to say, it's a bit difficult, because it contains some allusions which are by now rather obscure.

Please, don't be daunted!

I will post an extensive summary and notes.

But know that once we get past this chapter, everything else will be easier, I promise :)

Equally important:

As we start discussing the book tomorrow, please do not be shy to contribute to the discussion, share your thoughts and impressions, ask questions, draw parallels, and whatever!

Just, you know the drill, no spoilers if you're reading ahead :)