Works of Thomas Hardy discussion

The Mayor of Casterbridge

>

The Mayor of Casterbridge: 5th thread: Chapter 37-45

A Little More . . .

The gossip of the Casterbridge villagers focuses on the inequality between Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae, although opinions differ as to which young person is marrying below his or her station. This discussion reflects the importance in Casterbridge society of status, which is based on wealth, success, popularity, and modesty.

Elizabeth-Jane does not confess to Henchard about her relationship with Farfrae. Because this situation is presented from Henchard’s anxious and possessive perspective, and not from Elizabeth-Jane’s, it seems that Elizabeth-Jane does not feel as close a connection with Henchard as he feels with her.

Henchard spying allows him to see Newson’s return to Casterbridge before the secret it out. Henchard knows he is cornered with no where to go now:

”He stood in dark despair, obscured by “the shade from his own soul” A quote from Shelley’s ”The Revolt of Islam", Canto VIII, stanza vi.

Henchard does not delay the inevitable and tells Elizabeth-Jane that she should meet the man, who Henchard knows to be Newson. Elizabeth-Jane, despite her discretion with respect to her stepfather, does not want him to leave her life. Although she has every reason to distrust Henchard, Elizabeth-Jane does care for him.

Elizabeth-Jane, typically self-effacing, assumes that Henchard’s departure is all her fault. How difficult it must have been for Elizabeth to leave Henchard at the second bridge, the edge of town. Losing Elizabeth-Jane is the final tragedy in Henchard’s life and his fall from mayor of Casterbridge to friendless wanderer is complete. He recognizes his own fault in much of this fall from prominence.

Newson’s treatment of Elizabeth-Jane is sharply contrasted to Henchard’s: Newson sees and values Elizabeth-Jane, but not because of her treatment of him.

Elizabeth-Jane has been infinitely patient and forgiving, but the lie Henchard told Newson is unforgiveable in her mind. Throughout the novel, it has been clear that Elizabeth-Jane cared for Newson, and did not want to lose her connection to her father, despite Henchard’s attempts to replace Newson in her affections. Elizabeth is described by Henchard as having a “strict nature”, and so he knows once the truth is out, she will turn her back on him, that’s why he leave. That’s why he extracts the promise from her to not forget him. Elizabeth is compassionate, but she can also be rigid. We saw this side of her when Lucetta confessed her past with Henchard, and Elizabeth told her she could therefore only marry Henchard. So her reaction to the truth felt in character to me.

Newson assumes the role of father seamlessly, with his positive focus on the future and his offer of monetary support. And Farfrae seems extremely glad to be rid of Henchard.

I'm very curious to hear all of your thoughts . . . .

The gossip of the Casterbridge villagers focuses on the inequality between Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae, although opinions differ as to which young person is marrying below his or her station. This discussion reflects the importance in Casterbridge society of status, which is based on wealth, success, popularity, and modesty.

Elizabeth-Jane does not confess to Henchard about her relationship with Farfrae. Because this situation is presented from Henchard’s anxious and possessive perspective, and not from Elizabeth-Jane’s, it seems that Elizabeth-Jane does not feel as close a connection with Henchard as he feels with her.

Henchard spying allows him to see Newson’s return to Casterbridge before the secret it out. Henchard knows he is cornered with no where to go now:

”He stood in dark despair, obscured by “the shade from his own soul” A quote from Shelley’s ”The Revolt of Islam", Canto VIII, stanza vi.

Henchard does not delay the inevitable and tells Elizabeth-Jane that she should meet the man, who Henchard knows to be Newson. Elizabeth-Jane, despite her discretion with respect to her stepfather, does not want him to leave her life. Although she has every reason to distrust Henchard, Elizabeth-Jane does care for him.

Elizabeth-Jane, typically self-effacing, assumes that Henchard’s departure is all her fault. How difficult it must have been for Elizabeth to leave Henchard at the second bridge, the edge of town. Losing Elizabeth-Jane is the final tragedy in Henchard’s life and his fall from mayor of Casterbridge to friendless wanderer is complete. He recognizes his own fault in much of this fall from prominence.

Newson’s treatment of Elizabeth-Jane is sharply contrasted to Henchard’s: Newson sees and values Elizabeth-Jane, but not because of her treatment of him.

Elizabeth-Jane has been infinitely patient and forgiving, but the lie Henchard told Newson is unforgiveable in her mind. Throughout the novel, it has been clear that Elizabeth-Jane cared for Newson, and did not want to lose her connection to her father, despite Henchard’s attempts to replace Newson in her affections. Elizabeth is described by Henchard as having a “strict nature”, and so he knows once the truth is out, she will turn her back on him, that’s why he leave. That’s why he extracts the promise from her to not forget him. Elizabeth is compassionate, but she can also be rigid. We saw this side of her when Lucetta confessed her past with Henchard, and Elizabeth told her she could therefore only marry Henchard. So her reaction to the truth felt in character to me.

Newson assumes the role of father seamlessly, with his positive focus on the future and his offer of monetary support. And Farfrae seems extremely glad to be rid of Henchard.

I'm very curious to hear all of your thoughts . . . .

Thank you Bridget and Jean for all the additional details on the text and the writing work of Thomas Hardy and Emma.

Thank you Bridget and Jean for all the additional details on the text and the writing work of Thomas Hardy and Emma. I noticed some discrepancies which may go otherwise unnoticed. I am still wondering if Elizabeth-Jane knows that Henchard sold his wife and daughter. Did I miss textual evidence?

The likeliness of Newson's return, but also the rapprochement of Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae - the man who has supplanted him in business and who now is the mayor of Casterbridge - are both threats to Henchard's survival. Donald's expressions of love and gifts to the girl he wishes to marry, Elizabeth’s long walks in the countryside towards an elevation where she enjoys gazing at the distant sea, recall (view spoiler)

In the same spirit of indiscretion born of jealousy, Henchard spies on Elizabeth with a telescope and discovered Newson arriving on the very same strategical Budmouth road, and understood that the seaman has not disappeared from their lives. Henchard's world is shattered, just as (view spoiler)

Henchard's jealousy has perhaps some falsely Oedipal roots - as (view spoiler) and I also agree with Bridget and Pamela on parents' difficulty of seeing their children taking off.

Newson's account of how he came to Casterbridge on Henchard's trail corroborates Peter's observation that we saw a mysterious seaman at Peter's Finger who did not appear then until chapter 41. Newson is described, like Farfrae, as another "Mephistophelian Visitant" in the essay I mentioned above by JO Bailey in 1946. Newson is one of those intermittently recurring protagonists who caused a major disruption in Henchard's balance and triggered events likely to ruin his life and hopes, such as the furmity woman and Jopp.

Henchard's departure in chapter 43 is a reversed mirror image of his arrival at Weydon Prior in chapter 1. He has bought a new yellow basket and work clothes, the same as he wore more than twenty years earlier, and cleaned his tools. These concrete details on his clothes, old and new ones, the journeyman's and the Mayor's clothes, mirror Henchard's ascension and downfall. He goes away from Casterbridge, as anonymous and more lonely, even more unnoticed as he arrived at Weydon Prior, but conscientiously carrying his burden.

He went secretly and alone, not a soul of the many who had known him being aware of his departure.

"I—Cain—go alone as I deserve—an outcast and a vagabond."

Henchard's thought of Cain enhances the burden he is bearing, as Cain's fate in Genesis 4 illustrates a man's utmost culpability and his tortured conscience. Cain ran away from his house after having killed his brother Abel but could never run away from omnipresent and omniscient God and His watchful eye.

The following description offers a drawing perspective with a slightly dramatic and perhaps ominous note:

[Elizabeth-Jane] watched his form diminish across the moor, the yellow rush-basket at his back moving up and down with each tread, and the creases behind his knees coming and going alternately till she could no longer see them.

First, thank you Bridget for the illustration and links to further information. More and more I am coming to realize that the setting is as much a character in this novel as any flesh and blood human being.

First, thank you Bridget for the illustration and links to further information. More and more I am coming to realize that the setting is as much a character in this novel as any flesh and blood human being.Claudia Your insights and attention to detail always make me think and reflect.

The beginning paragraph of this chapter made me smile. How petty but how true are the reactions of the town’s ’superior young ladies’ and the phrase they all ‘reverted to their normal courses.’ This paragraph of light humour and human foibles sets up the anguish of the coming chapter.

Now, I must confess to thinking the tone and the style of writing in this chapter seems slightly at odds with the rest of the novel. Is it just my recent awareness of Hardy’s wife’s hand in the novel?

Letters come into play again in this chapter. Earlier in the novel Elizabeth-Jane received a mysterious letter that we learn later was sent by her mother to help her meet with Farfrae. Now, she has received another anonymous letter to meet with a stranger. In this chapter Elizabeth-Jane meets not her lover but her father. The fact that she meets her father at Farfrae’s home and she and Farfrae now plan to marry and her father wants to help pay for the wedding is a wonderful balance in the structure of the plot.

We cannot ignore Henchard in this chapter. I felt echoes of Shakespeare’s Othello’’s declaration of love towards Desdemona echoed in Henchard’s ‘I loved ‘ee late I loved ‘ee well.’ When Henchard reverts back to his humble beginnings as he entered Casterbridge by changing his clothes and carrying his tools, we see his end, which is now mimicking his beginnings.

Claudia wrote: "Henchard's thought of Cain enhances the burden he is bearing, as Cain's fate in Genesis 4 illustrates a man's utmost culpability and his tortured conscience. Cain ran away from his house after having killed his brother Abel but could never run away from omnipresent and omniscient God and His watchful eye....."

Claudia wrote: "Henchard's thought of Cain enhances the burden he is bearing, as Cain's fate in Genesis 4 illustrates a man's utmost culpability and his tortured conscience. Cain ran away from his house after having killed his brother Abel but could never run away from omnipresent and omniscient God and His watchful eye....."As Peter said, Claudia, your post is full of fascinating observations. I love this comparison of Henchard to Cain. Like Cain, he is aware of his sin and that he, too, is unable to escape the consequences of his actions. Like Cain, Henchard is driven by jealousy and allows it to destroy him.

I was also a little taken aback by Mr. Newson's reaction to Henchard's lie. I get that he is an easygoing, good-natured fellow, but I struggle with imagining how anyone could think being falsely told that his child is dead a joke. Now that he has the context provided by Farfrae and Elizabeth-Jane herself, he knows that it wasn't meant as a joke--Henchard wanted Newson to spend the rest of his life without ever seeing his daughter again. Yet he is taking up for him!

I also noticed and thought interesting the interchange between Elizabeth-Jane and Henchard when she reveals the letter from Newson and his request to meet with her. It was previously stated, in regards to the courtship, that "not a hint of the matter was thrown out to her stepfather by Elizabeth herself or by Farfrae either" (236). But when she tells Henchard about the letter, she surmises that "Donald is at the bottom of the mystery, and that it is a relation of his who wants to pass an opinion on his choice" (238). Was this intended to be the way she announces her engagement to him? Could this have been a blip caused by shifting writers, as has been discussed (although both statements are in the same chapter)? It just felt a little odd to me.

Every time I have been to Maiden Castle I have been almost blown off my feet! These Neolithic earthworks are often like that though. Badbury Rings, which is referred to in some of Hardy's poems is like that as well, and Maumbury Rings - "The Ring" - which features prominently as a meeting place in The Mayor of Casterbridge too, although it's smaller in area.

It is just Thomas Hardy who calls Maiden Castle "Mai' Dun" - one of his approximations like "Budmouth" for Weymouth - rather than inventing another name.

Perhaps you can see that there's a lot of chalk between the grassy mounds, and this is where you walk. You aren't aware of the actual shape when you are there, just the wind ... 😂 To appreciate the scale, the tiny blocks in the bottom left of Bridget's photo (great find Bridget!) are cars. To add to the English Heritage page, here's wiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maiden_...

Once I picked up an odd-looking stone on one of the tracks round Maiden Castle to find it was a flint! It made me feel quite light-headed, to realise that the last person to hold it in their palm must have been a prehistoric person, skilfully chipping away at a hard stone to make a useful tool. What a privilege. 🙂

Great comments all! Sorry for my brevity today, but I've been travelling all day, and won't be back in the Casterbridge area until a week after we finish The Mayor of Casterbridge.

It is just Thomas Hardy who calls Maiden Castle "Mai' Dun" - one of his approximations like "Budmouth" for Weymouth - rather than inventing another name.

Perhaps you can see that there's a lot of chalk between the grassy mounds, and this is where you walk. You aren't aware of the actual shape when you are there, just the wind ... 😂 To appreciate the scale, the tiny blocks in the bottom left of Bridget's photo (great find Bridget!) are cars. To add to the English Heritage page, here's wiki https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maiden_...

Once I picked up an odd-looking stone on one of the tracks round Maiden Castle to find it was a flint! It made me feel quite light-headed, to realise that the last person to hold it in their palm must have been a prehistoric person, skilfully chipping away at a hard stone to make a useful tool. What a privilege. 🙂

Great comments all! Sorry for my brevity today, but I've been travelling all day, and won't be back in the Casterbridge area until a week after we finish The Mayor of Casterbridge.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Every time I have been to Maiden Castle I have been almost blown off my feet! These Neolithic earthworks are often like that though. Badbury Rings are like that too, and Maumbury Rings ("The Ring" ..."

Jean - I'm so glad you added how it felt to experience Maiden Castle in person. I'm sure the pictures don't do it justice. I Amazing that you found flint, and I loved how you felt connected to histroy through that one piece!

Claudia, I'm so glad you brought up the symmetry of Henchard leaving Casterbridge just as he arrived. I forgot to mention that, and I think it's such a poignant part of the story. And the connection to Cain is spot on as well. As are Peter's thoughts about the Othello connection, I like that very much. I've been thinking also about Henchard and King Lear, how he tries to control his daughters, how he slowly goes mad. Sometimes it feels like Henchard tends towards madness.

Cindy, I have a hard time with Newsom's reaction to Henchard's lie as well. In fact, I have a hard time with lots of choices Newsom makes. It's a minor thing, but he's the one who funded the skimmington ride, not a great decision IMHO. The more serious issue I have with him is that he allowed his daughter to think he was dead for at least five years.

When he feigned his death, it was to give Susan the chance to go back to Henchard. Did Newsom know for sure Henchard was alive when he made that decision? Did he investigate that before he decided to "play dead"? I doubt it, because Susan didn't even know Henchard was in Casterbridge until the furmity woman in Weydon Priors told her. Basically, he abandoned his wife and child and is coming back five years later to make sure they are okay. Elizabeth doesn't like Henchard lying, how does she feel about Newsom's lies?

Jean - I'm so glad you added how it felt to experience Maiden Castle in person. I'm sure the pictures don't do it justice. I Amazing that you found flint, and I loved how you felt connected to histroy through that one piece!

Claudia, I'm so glad you brought up the symmetry of Henchard leaving Casterbridge just as he arrived. I forgot to mention that, and I think it's such a poignant part of the story. And the connection to Cain is spot on as well. As are Peter's thoughts about the Othello connection, I like that very much. I've been thinking also about Henchard and King Lear, how he tries to control his daughters, how he slowly goes mad. Sometimes it feels like Henchard tends towards madness.

Cindy, I have a hard time with Newsom's reaction to Henchard's lie as well. In fact, I have a hard time with lots of choices Newsom makes. It's a minor thing, but he's the one who funded the skimmington ride, not a great decision IMHO. The more serious issue I have with him is that he allowed his daughter to think he was dead for at least five years.

When he feigned his death, it was to give Susan the chance to go back to Henchard. Did Newsom know for sure Henchard was alive when he made that decision? Did he investigate that before he decided to "play dead"? I doubt it, because Susan didn't even know Henchard was in Casterbridge until the furmity woman in Weydon Priors told her. Basically, he abandoned his wife and child and is coming back five years later to make sure they are okay. Elizabeth doesn't like Henchard lying, how does she feel about Newsom's lies?

I don't know about this chapter. Makes me very sad. I'm surprised in a way that Elizabeth-Jane would take the side she did. She doesn't know that she is Henchard's stepdaughter — yet she acts as if Newson has more right to her than Henchard. Or are we to assume that Newson that although not said in the copy, that Newson has explained that there was a first daughter, Henchard's, with the same name who indeed had died? Henchard knew, not only because of Susan's letter, but Newson himself.

I don't know about this chapter. Makes me very sad. I'm surprised in a way that Elizabeth-Jane would take the side she did. She doesn't know that she is Henchard's stepdaughter — yet she acts as if Newson has more right to her than Henchard. Or are we to assume that Newson that although not said in the copy, that Newson has explained that there was a first daughter, Henchard's, with the same name who indeed had died? Henchard knew, not only because of Susan's letter, but Newson himself. But Elizabeth-Jane doesn't have knowledge of either the letter or the news that there were two daughters. While Henchard did treat her harshly, she has always been forgiving to him, and he has always been near her as someone she could have turned to at any time. Then to add that she wasn't honest with him about her courtship. It's like she sealed his coffin by not trying to understand and appreciate where he is coming from.

Peter wrote: "Now, I must confess to thinking the tone and the style of writing in this chapter seems slightly at odds with the rest of the novel. Is it just my recent awareness of Hardy’s wife’s hand in the novel?"

Speaking of inconsistencies in the novel, here's another one. This description of Henchard troubles me:

The question of his remaining in Casterbridge was forever disposed of by this closing in of Newson on the scene. Henchard was not the man to stand the certainty of condemnation on a matter so near his heart. And being an old hand at bearing anguish in silence, and haughty withal, he resolved to make as light as he could of his intentions, while immediately taking his measures."

Does Henchard really "bear anguish in silence"? It seems to me throughout the novel Henchard is very vocal about his anguish. It's what drives him to confront Farfrae in the barn. Its what makes him try to manipulate Lucetta into marrying him. When he's frustrated with Able Whittle being late to work, he vents his frustration in a very public way.

This paragraph just doesn't seem like the right description of Henchard.

Speaking of inconsistencies in the novel, here's another one. This description of Henchard troubles me:

The question of his remaining in Casterbridge was forever disposed of by this closing in of Newson on the scene. Henchard was not the man to stand the certainty of condemnation on a matter so near his heart. And being an old hand at bearing anguish in silence, and haughty withal, he resolved to make as light as he could of his intentions, while immediately taking his measures."

Does Henchard really "bear anguish in silence"? It seems to me throughout the novel Henchard is very vocal about his anguish. It's what drives him to confront Farfrae in the barn. Its what makes him try to manipulate Lucetta into marrying him. When he's frustrated with Able Whittle being late to work, he vents his frustration in a very public way.

This paragraph just doesn't seem like the right description of Henchard.

Pamela and Bridget, good questions! These are definitely inconsistencies. I don't imagine Henchard bearing anything in silence. He has proved to be a man of rash (and wrong) decisions. Was Elizabeth-Jane actually told the whole story, the selling of her mother and the first daughter whose name she is bearing?

Pamela and Bridget, good questions! These are definitely inconsistencies. I don't imagine Henchard bearing anything in silence. He has proved to be a man of rash (and wrong) decisions. Was Elizabeth-Jane actually told the whole story, the selling of her mother and the first daughter whose name she is bearing?

Claudia wrote: "Pamela and Bridget, good questions! These are definitely inconsistencies. I don't imagine Henchard bearing anything in silence. He has proved to be a man of rash (and wrong) decisions. Was Elizabet..."

I'm glad I'm not the only one who sees the inconsistencies.

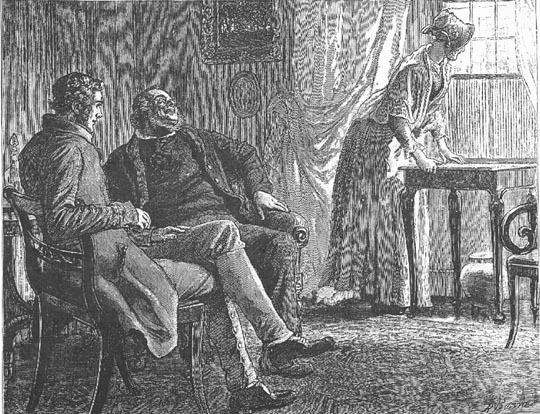

We are truly nearing the end of the novel now. Two more chapters to go (and a couple poems as well). Before moving onto Chapter 44, there was an illustration by Robert Barnes for Chapter 43, which I neglected to post. Here it is.

Elizabeth-Jane reunited with "Captain" Newson, Robert Barnes

My sincer apologies for not posting this illustration with my Summary.

Now, onward to Chapter 44. Depending on which version you have, the chapter may be very different.

I'm glad I'm not the only one who sees the inconsistencies.

We are truly nearing the end of the novel now. Two more chapters to go (and a couple poems as well). Before moving onto Chapter 44, there was an illustration by Robert Barnes for Chapter 43, which I neglected to post. Here it is.

Elizabeth-Jane reunited with "Captain" Newson, Robert Barnes

My sincer apologies for not posting this illustration with my Summary.

Now, onward to Chapter 44. Depending on which version you have, the chapter may be very different.

CHAPTER 44 - Summary

From the American 1886 first edition, and also the editions after 1895

Henchard travels back to Weydon-Priors and visits the location of the fair where he made the error of selling his wife and daughter. He visits this place as an act of penance and feels fully the bitterness of his situation. He had planned to travel far away from Casterbridge, but because his mind is on Elizabeth-Jane, he continues circling distantly around the town.

Henchard obtains work again as a hay-trusser and finds himself in exactly the same circumstance in life where he found himself twenty-five years earlier. He often thinks as he works of the people everywhere dying before their time, while he, an outcast who no one will miss, lives on.

One day, Henchard hears the word “Casterbridge” spoken by someone in a passing wagon and runs to the road to inquire about news from the town. He asks about a wedding and hears that one is taking place on Martin’s Day. He thinks of writing to Elizabeth-Jane, remembering that she had said she wished him to be at her wedding, but he is unsure how to reverse his own self-willed seclusion.

Henchard decides to arrive at the wedding, in the evening, so as to make as little disruption as possible. He travels toward Casterbridge, he stops to buy himself some spruced up clothing in an attempt to fit in as a wedding guest and not further embarrass Elizabeth. He also buys Elizabeth-Jane a gift of a goldfinch in a cage.

He arrives at Farfrae’s house that evening and sees the lively proceedings within. He can hear Farfrae’s voice singing. The door is open and everything inside is brightly lit. Henchard is embarrassed to enter and goes to the back door instead and sends a servant to pass a message to his stepdaughter.

Henchard watches the dance underway in the other room and sees one man who dances particularly grandly. This happy man, Elizabeth-Jane’s dance partner for that number, is Newson.

Elizabeth-Jane appears, having been summoned by the servant. She tells Henchard she might once have cared for him, but she no longer can knowing how much he deceived her. Henchard cannot begin to explain his own limited knowledge and confusion about these matters and only apologizes for distressing her at such a happy time and swears he will not trouble her again.

From the American 1886 first edition, and also the editions after 1895

Henchard travels back to Weydon-Priors and visits the location of the fair where he made the error of selling his wife and daughter. He visits this place as an act of penance and feels fully the bitterness of his situation. He had planned to travel far away from Casterbridge, but because his mind is on Elizabeth-Jane, he continues circling distantly around the town.

Henchard obtains work again as a hay-trusser and finds himself in exactly the same circumstance in life where he found himself twenty-five years earlier. He often thinks as he works of the people everywhere dying before their time, while he, an outcast who no one will miss, lives on.

One day, Henchard hears the word “Casterbridge” spoken by someone in a passing wagon and runs to the road to inquire about news from the town. He asks about a wedding and hears that one is taking place on Martin’s Day. He thinks of writing to Elizabeth-Jane, remembering that she had said she wished him to be at her wedding, but he is unsure how to reverse his own self-willed seclusion.

Henchard decides to arrive at the wedding, in the evening, so as to make as little disruption as possible. He travels toward Casterbridge, he stops to buy himself some spruced up clothing in an attempt to fit in as a wedding guest and not further embarrass Elizabeth. He also buys Elizabeth-Jane a gift of a goldfinch in a cage.

He arrives at Farfrae’s house that evening and sees the lively proceedings within. He can hear Farfrae’s voice singing. The door is open and everything inside is brightly lit. Henchard is embarrassed to enter and goes to the back door instead and sends a servant to pass a message to his stepdaughter.

Henchard watches the dance underway in the other room and sees one man who dances particularly grandly. This happy man, Elizabeth-Jane’s dance partner for that number, is Newson.

Elizabeth-Jane appears, having been summoned by the servant. She tells Henchard she might once have cared for him, but she no longer can knowing how much he deceived her. Henchard cannot begin to explain his own limited knowledge and confusion about these matters and only apologizes for distressing her at such a happy time and swears he will not trouble her again.

Chapter 44 Summary - From the original English first edition 1886

Henchard heads towards Weydon Priors in his solitary, depressed manner. "His heart was so exacerbated at parting from the firl that he could not face an inn . . . . he lay down under a wheat-rick . . . The very heaviness of his soul caused him to sleep profoundly".

After five days walking he arrives in Weydon Priors, and like the other version he recalls his past mistakes and takes stock of his life. "He had been sorry for all this long ago; but his attempts to replace ambition by love had been fully foiled as his ambition itself. His wronged wife had foiled them by a fraud so grandly simple as to be almost a virtue. It was an odd sequence that out of all this wronging of social law came that flower of Nature, Elizabeth."

He had intended to head farther away from Casterbridge, but his thoughts of Elizabeth won't let him, and he circles around the town. Eventually he finds himself just outside Casterbridge, but he is unable to bring himself to enter the town.

"the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities of amelioration to a minimum . . . stood in the way of all that [ie: going to Casterbridge once agai]. He had no wish to make an arena a second time of that world that had become a mere painted scene to him."

The narrator then takes over and says if Henchard had been able to enter Casterbridge he would have seen Elizabeth and Farfrae's wedding reception. The chapter ends with Elizabeth and Newson dancing.

Henchard heads towards Weydon Priors in his solitary, depressed manner. "His heart was so exacerbated at parting from the firl that he could not face an inn . . . . he lay down under a wheat-rick . . . The very heaviness of his soul caused him to sleep profoundly".

After five days walking he arrives in Weydon Priors, and like the other version he recalls his past mistakes and takes stock of his life. "He had been sorry for all this long ago; but his attempts to replace ambition by love had been fully foiled as his ambition itself. His wronged wife had foiled them by a fraud so grandly simple as to be almost a virtue. It was an odd sequence that out of all this wronging of social law came that flower of Nature, Elizabeth."

He had intended to head farther away from Casterbridge, but his thoughts of Elizabeth won't let him, and he circles around the town. Eventually he finds himself just outside Casterbridge, but he is unable to bring himself to enter the town.

"the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities of amelioration to a minimum . . . stood in the way of all that [ie: going to Casterbridge once agai]. He had no wish to make an arena a second time of that world that had become a mere painted scene to him."

The narrator then takes over and says if Henchard had been able to enter Casterbridge he would have seen Elizabeth and Farfrae's wedding reception. The chapter ends with Elizabeth and Newson dancing.

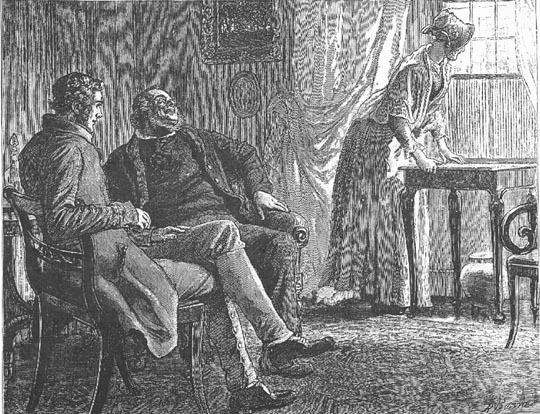

There is a Robert Barnes illustration for the first version of this chapter. The one where Henchard returns to Casterbridge and meets with Elizabeth at her wedding.

"I have done wrong in coming to 'ee . . . I'll never, never trouble 'ee again, Elizabeth Jane.", by Robert Barnes

Given how Henchard goes back to Weydon Priors, I thought it might be interesting to see Robert Barnes first illustration again. Just to compare how much Henchard has changed in 25 years. I think Barnes does a fabulous job of showing the changed man.

"I have done wrong in coming to 'ee . . . I'll never, never trouble 'ee again, Elizabeth Jane.", by Robert Barnes

Given how Henchard goes back to Weydon Priors, I thought it might be interesting to see Robert Barnes first illustration again. Just to compare how much Henchard has changed in 25 years. I think Barnes does a fabulous job of showing the changed man.

A Little More . . .

When Henchard returns to Weydon-Priors, the novel has come full circle. Through the years that have passed, Henchard has changed. The major change is that he has come to love his “daughter” when he once gave up his family members willingly. And yet he is also warped by self-hatred.

Henchard has also lost the ambition that once ruled his life and pushed him to become the mayor of Casterbridge. He sees the loneliness that pervades his life and realizes that he needs others.

It's interesting that in the first English edition, Henchard doesn't return to Casterbridge. He comes close, but he can't bring himself to cross that boundary. Hardy gives us, as a reason for this, "the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities", which sounds an awful lot like the ending of Thomas Hardy: Tess of the D'Urbevilles' to me: "the President of the Immortals, in Aeschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess". Both conveying the idea that fate plays more of a hand than self-determination in our lives.

In the alternate ending, Henchard receives news of Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae’s wedding, and of Casterbridge, by word of mouth. Despite Henchard’s choice to isolate himself, he is not beyond the reach of society, which has been connected throughout the novel with news and gossip spread by villagers.

Henchard wants to go to the wedding, unable to resist the appeal of seeing Elizabeth-Jane. The gift he buys of a bird in a caage reflects how he has always seen the girl: a possession in a cage to be admired and enjoyed.

The liveliness of the wedding party is intimidating to Henchard because he no longer sees himself as part of the world of splendor he once enjoyed. He is outside looking in on success, as Susan and Elizabeth-Jane once gazed in at him at a brightly lit dinner at the Golden Crown.

Newson is fulfilling all that Elizabeth-Jane needs in a father, as he dances with her at her wedding.

Elizabeth-Jane shares her changed opinion with Henchard. She has never, before this, directly stood up to her stepfather. She has avoided him, moved away from him, and forgiven him, but she has reached the point when she cannot forgive. This is, despite all he has experienced, the most painful blow to Henchard.

When Henchard returns to Weydon-Priors, the novel has come full circle. Through the years that have passed, Henchard has changed. The major change is that he has come to love his “daughter” when he once gave up his family members willingly. And yet he is also warped by self-hatred.

Henchard has also lost the ambition that once ruled his life and pushed him to become the mayor of Casterbridge. He sees the loneliness that pervades his life and realizes that he needs others.

It's interesting that in the first English edition, Henchard doesn't return to Casterbridge. He comes close, but he can't bring himself to cross that boundary. Hardy gives us, as a reason for this, "the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities", which sounds an awful lot like the ending of Thomas Hardy: Tess of the D'Urbevilles' to me: "the President of the Immortals, in Aeschylean phrase, had ended his sport with Tess". Both conveying the idea that fate plays more of a hand than self-determination in our lives.

In the alternate ending, Henchard receives news of Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae’s wedding, and of Casterbridge, by word of mouth. Despite Henchard’s choice to isolate himself, he is not beyond the reach of society, which has been connected throughout the novel with news and gossip spread by villagers.

Henchard wants to go to the wedding, unable to resist the appeal of seeing Elizabeth-Jane. The gift he buys of a bird in a caage reflects how he has always seen the girl: a possession in a cage to be admired and enjoyed.

The liveliness of the wedding party is intimidating to Henchard because he no longer sees himself as part of the world of splendor he once enjoyed. He is outside looking in on success, as Susan and Elizabeth-Jane once gazed in at him at a brightly lit dinner at the Golden Crown.

Newson is fulfilling all that Elizabeth-Jane needs in a father, as he dances with her at her wedding.

Elizabeth-Jane shares her changed opinion with Henchard. She has never, before this, directly stood up to her stepfather. She has avoided him, moved away from him, and forgiven him, but she has reached the point when she cannot forgive. This is, despite all he has experienced, the most painful blow to Henchard.

Well, there is a lot going on in this chapter. I hope my explanations of both versions have not confused you too much. I'm curious which version everyone has. My edition used the 1886 English edition, the one where Henchard does NOT go back to Casterbridge, but it also provided the second ending as an Appendix.

I was also able to find the second ending on Project Gutenberg, and here is a link for anyone who needs/wants it.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/...

As always, I'm very curious to hear your thoughts!

And remember, Friday, August 22nd we will have another poem led by Connie. Saturday is a FREE day. We will continue with the final chapter 45 on Sunday, August 24th

Over to you :-)

I was also able to find the second ending on Project Gutenberg, and here is a link for anyone who needs/wants it.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/...

As always, I'm very curious to hear your thoughts!

And remember, Friday, August 22nd we will have another poem led by Connie. Saturday is a FREE day. We will continue with the final chapter 45 on Sunday, August 24th

Over to you :-)

Claudia wrote: "Was Elizabeth-Jane actually told the whole story, the selling of her mother and the first daughter whose name she is bearing?...."

Claudia wrote: "Was Elizabeth-Jane actually told the whole story, the selling of her mother and the first daughter whose name she is bearing?...."Sorry--this hearkens back to the previous chapter, and the question asked by Pamela and Claudia. I think possibly Elizabeth-Jane was told the story of what happened before she was born and her true paternity. When she enters Farfrae's home and finds Newson there, their reunion is described as "an affecting one, apart from the question of paternity . . . When the true facts came to be handled the difficulty of restoring her to her old belief in Newson was not so great as might have seemed likely, for Henchard's conduct itself was proof that those facts were true" (240). It doesn't say specifically that she is told about her mother and half-sister being sold to Newson, but both Newson and Farfrae know the story. Since they are attempting to "restore" her belief of Newson as her father and discredit Henchard as such, it would only make sense (to me) that they would tell the truth about ALL of it. Hardy deliberately uses the words "the true facts" to describe what they told her, and it mentions that the difficulty of getting her to believe the truth may have been great except for the fact that Henchard had skulked out of town. This could point to the outrageousness of the related story as something that a person would have trouble believing true of someone that they had trusted. I could imagine Elizabeth-Jane, loyal as she is, refusing to believe that Henchard could do such a dastardly thing, but ultimately recognizing Henchard's mystifying flight as an appropriate response to the magnitude of his offense.

Cindy wrote: It doesn't say specifically that she is told about her mother and half-sister being sold to Newson, but both Newson and Farfrae know the story. Since they are attempting to "restore" her belief of Newson as her father and discredit Henchard as such, it would only make sense (to me) that they would tell the truth about ALL of it. Hardy deliberately uses the words "the true facts" to describe what they told her...

Cindy wrote: It doesn't say specifically that she is told about her mother and half-sister being sold to Newson, but both Newson and Farfrae know the story. Since they are attempting to "restore" her belief of Newson as her father and discredit Henchard as such, it would only make sense (to me) that they would tell the truth about ALL of it. Hardy deliberately uses the words "the true facts" to describe what they told her...Thank you Cindy! Your explanation and quote make sense!

Thank you Bridget for these great comments on a bittersweet chapter. Henchard appears as a lonely and sad witness of Elizabeth-Jane's wedding with Farfrae and of restored family happiness where Richard Newson has now found his place, while Henchard is now an outsider, even an outcast.

My edition (Wordsworth Classics) corresponds most probably to those after 1895, i.e the chapter closes when Henchard is taking leave and Elizabeth-Jane has not even time to watch him go:

Then, before she could collect her thoughts, Henchard went out from her rooms, and departed from the house by the back way as he had come; and she saw him no more. (ominous...)

Interesting parallel between this scene and the initial one at the King's Arms, as you well mentioned, Bridget. This is one more reversed mirror image of an opening scene and this shows how much Henchard's story has gone full circle. Even if this is of his own making, it is nevertheless heartbreaking.

Thank you also for mentioning the quote from the first edition. This, and the quote from Tess of the D’Urbervilles is definitely a deep topic.

I am certain that Peter will enlighten us about the illustrations!

Don't worry Bridget about the one posted afterwards!

(PS - There are some more striking similarities in this chapter with Les Misérables, even if the characters and their issues are different.)

Bridget, thank you so much for the details on both versions. I really appreciate this, as I have the newer version, and have to say--I much prefer the original!

Bridget, thank you so much for the details on both versions. I really appreciate this, as I have the newer version, and have to say--I much prefer the original! I find Elizabeth Jane's thoughts and comments in these last chapters ring a little false, and could easily see them as an "add-on." Henchard wanting to go to the wedding but denying himself seems much more believable to me, and I love the line you quoted:

"the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities of amelioration to a minimum . . . stood in the way of all that."

In the newer version, I did like the bird-in-a-cage gift, and the ominous ending to the chapter though.

Bridget .

Bridget .I thank you for providing not only the current illustration but bringing to our attention again the early illustration. And how right you are! 25 years has cast many changes on many of our principal characters. Perhaps it is best to look at them in chronological order to appreciate the changes best.

Barnes’s first illustration places our road-weary couple in an outdoor setting. Their clothes speak to Henchard and Susan’s rural roots, their apparent poverty, and the fact they have a very young child. Henchard is portrayed as being tall and lanky. As would be expected in a late 19C illustration, he has the dominant position. It is he who takes the initiative to speak to another person, to ask for direction and information.

His wife is placed behind him. She looks weary. Her full attention is focussed on her young child. Susan’s pose with Elizabeth-Jane fits comfortably into the iconography of the mother-child tableau which has passed down through history and finds its origins in the pose of Mary and the Christ child. Placing the illustration in a broad sense Barnes has offered us a view of 19C rural poverty, yet as we look at the illustration we notice how straight and tall our two main figures are. Despite their obvious situation in life, there remains a quiet pride in their postures.

In this chapter’s illustration we see two adults, dressed well, whose physical attributes show they are both confident and assertive. Henchard especially is presented as being a man of strength and assertiveness. His hand is positioned such that it is apparent he has a point to make, and he intends to make that point clearly and forcefully. Personally, I think Henchard looks too forceful and not enough contrite given what this illustration recounts from the text. What do others think?

Elizabeth-Janet’s physical pose is one that I find curious. She is leaning slightly backward, her hand suggests to me that she is deflecting what Henchard is saying. They are inside and it is evident that the home is one of substance which is a clear difference from the earlier illustration set outside in a rural setting.

I confess that I find the illustration for this chapter disappointing. To me, it does not convey what my mind read in the chapter. What do you think?

Peter wrote: " Bridget .

Peter wrote: " Bridget .I thank you for providing not only the current illustration but bringing to our attention again the early illustration. And how right you are! 25 years has cast many changes on many of ..."

His hand is positioned such that it is apparent he has a point to make, and he intends to make that point clearly and forcefully. Personally, I think Henchard looks too forceful and not enough contrite given what this illustration recounts from the text. : I agree with you! I find Henchard's attitude on this illustration definitely off-putting, which is more nuanced if we consider only the text.

Thank you Peter for your excellent explanations/interpretations of illustrations.

Peter wrote: " Bridget .

I thank you for providing not only the current illustration but bringing to our attention again the early illustration. And how right you are! 25 years has cast many changes on many of ..."

Thank you Peter for helping flesh out the illustrations. You always have such insightful comments.

After reading your post, I went back to look at the illustration again. I too find Elizabeth-Jane's pose curious. She's leaning away from Henchard, as if she doesn't want him there. Her left hand is behind her on the table; maybe to balance herself? Is she feeling off kilter? It reminded me of the illustration for chapter 19, the one where Henchard has just told her he's her father, and Elizabeth is leaning on the table with her hand behind her back. And it almost looks like Henchard is hurting her. There is some symmetry between that illustration and the one for today. Perhaps I should have compared those two instead.

As for Henchard, I thought his expression was sad and weary. I thought I could see depression in his face. I thought his hand was raised to protect himself from the words Elizabeth-Jane is saying . . . that she can't forgive him. Which is not to say that your interpretation is wrong at all. I can totally "read" the illustration exactly as you described it. Those were just my first impressions of the picture.

I thank you for providing not only the current illustration but bringing to our attention again the early illustration. And how right you are! 25 years has cast many changes on many of ..."

Thank you Peter for helping flesh out the illustrations. You always have such insightful comments.

After reading your post, I went back to look at the illustration again. I too find Elizabeth-Jane's pose curious. She's leaning away from Henchard, as if she doesn't want him there. Her left hand is behind her on the table; maybe to balance herself? Is she feeling off kilter? It reminded me of the illustration for chapter 19, the one where Henchard has just told her he's her father, and Elizabeth is leaning on the table with her hand behind her back. And it almost looks like Henchard is hurting her. There is some symmetry between that illustration and the one for today. Perhaps I should have compared those two instead.

As for Henchard, I thought his expression was sad and weary. I thought I could see depression in his face. I thought his hand was raised to protect himself from the words Elizabeth-Jane is saying . . . that she can't forgive him. Which is not to say that your interpretation is wrong at all. I can totally "read" the illustration exactly as you described it. Those were just my first impressions of the picture.

Kathleen wrote: "Bridget, thank you so much for the details on both versions. I really appreciate this, as I have the newer version, and have to say--I much prefer the original!

I find Elizabeth Jane's thoughts a..."

I agree with all your thoughts Kathleen. I like the simplicity of the ending where Henchard never returns to Casterbridge. I like Hardy's thoughts about the gods or fate playing a role. But I also really like the caged bird gift. We've had so many birds popping in and out of the story, it's a nice addition to the end.

I find Elizabeth Jane's thoughts a..."

I agree with all your thoughts Kathleen. I like the simplicity of the ending where Henchard never returns to Casterbridge. I like Hardy's thoughts about the gods or fate playing a role. But I also really like the caged bird gift. We've had so many birds popping in and out of the story, it's a nice addition to the end.

Kathleen wrote: "I find Elizabeth Jane's thoughts and comments in these last chapters ring a little false, and could easily see them as an "add-on"..."

Yes, me too. In fact, if it hadn't been for some very Thomas Hardy-esque expressions and thoughts, I would have suspected this too to have been penned by Emma.

For such emotional content, it feels very dry and disengaged. But the quotation you include "the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities of amelioration to a minimum . . . stood in the way of all that" and also the various mathematical and astronomical refences are typical of him. So I suspect Emma of some rather heavy editing and expansion perhaps of a shorter chapter. To me, she seems to be trying to draw the threads together to make sense, but making a few slips in the meantime!

And of course the editing later by Hardy himself, as explained so well by Bridget, further muddies the waters.

Yes, me too. In fact, if it hadn't been for some very Thomas Hardy-esque expressions and thoughts, I would have suspected this too to have been penned by Emma.

For such emotional content, it feels very dry and disengaged. But the quotation you include "the ingenious machinery contrived by the gods for reducing human possibilities of amelioration to a minimum . . . stood in the way of all that" and also the various mathematical and astronomical refences are typical of him. So I suspect Emma of some rather heavy editing and expansion perhaps of a shorter chapter. To me, she seems to be trying to draw the threads together to make sense, but making a few slips in the meantime!

And of course the editing later by Hardy himself, as explained so well by Bridget, further muddies the waters.

Cindy "I think possibly Elizabeth-Jane was told the story of what happened before she was born and her true paternity."

You argue this very well, but particularly after today's chapter I'm afraid I disagree that Elizabeth-Jane even knew her true parentage before this. And certainly did not know about the wife-selling. (I nearly said in answer to Claudia's query about maybe missing some textual evidence, that not to worry - there had not been any. And also how unlikely that would seem to have been, that Elizabeth-Jane still would not know ... (e.g. think of the "slip" about the colour of her hair as a baby, when Michael believed her to be his own) - but then this novel is full of well-kept secrets.

Here's a little more of the paragraph you quoted

"from whom she had been separated half-a-dozen years, as if by death, need hardly be detailed. It was an affecting one, apart from the question of paternity. Henchard’s departure was in a moment explained. When the true facts came to be handled the difficulty of restoring her to her old belief in Newson was not so great as might have seemed likely, for Henchard’s conduct itself was a proof that those facts were true. Moreover, she had grown up under Newson’s paternal care ..."

What this describes is their assumptions about Henchard's motives in leaving Casterbridge. But as we learn in today' s chapter 44, they are much more complex. And in fact Henchard makes great efforts to return as a "humble old friend" and fantasises about being accepted as an elderly man, treated affectionately and living with them in their home. (Though this seems a bit of a stretch to me! I think he would not feel this way for long).

It is another assumption that they would want to:

"discredit Henchard" In fact we learn in ch 44 that Newson has no malice towards Henchard, and says it was a "good joke" so although we might feel that they would naturally be tempted to "tell the truth about ALL of it" this is not what we are told has happened.

(For the record, I too find Newson's attitude unfathomable! It's passed off as being "like a good many rovers and sojourners among strange men and strange moralities", but I'm not sure this is a believable justification really.)

Even Elizabeth-Jane herself is not clear about what happened:

"you have deceived me so—so bitterly deceived me! You persuaded me that my father was not my father—allowed me to live on in ignorance of the truth for years; and then when he, my warm-hearted real father, came to find me, cruelly sent him away with a wicked invention of my death, which nearly broke his heart."

It is evident that she has now been told her true parentage, but not about the wife-selling. Since she is in a rare passion, wouldn't she have added this accusation in disgust?

On the other hand, Henchard assumes that she does know:

"Then you know all;"

and moreover keeps his own counsel. Hardy enumerates 3 things he could have said in his defence:

1. He himself had initially believed her to be his daughter, until Susan revealed the truth by letter. (I personally think that he did not protest his innocence at this point, because it would have laid the blame on her mother, and he did not wish Elizabeth-Jane - whom we are told he now truly loves - to receive this further blow.)

2. The lie he told to Newson was "the last desperate throw of a gamester" - we read at the time that it was the impulse of a moment, which he never expected to get away with, and again his rash gamble with Fate was because he "loved her affection better than his own honour".

3. "he did not sufficiently value himself" to argue his own case.

Henchard is a broken man. Partly because of his own feelings of guilt, but also perhaps because he believes Elizabeth-Jane "knows all" and he cannot believe that she would not as a consequence despise him for auctioning her mother like a piece of cattle.

But does she? It's ambiguous.

Someone asked how old Elizabeth-Jane is. She was 18 at the start, and has only been in Casterbridge for 3 years or so I think - 4 at the most. We could probably count the seasons, as the novel is based around the farming year. Including the months when they were travelling, she and Newson had been apart for 6 years (she told Henchard she was 12 when they came to England from Canada in ch 10, and its confirmed in this quotation. Also in ch 10, she says: "Father was lost last Spring".)

Therefore Elizabeth-Jane must still be in her early 20s. She had a loving, light-hearted father for almost 12 years, and had chosen a husband very like him in manner - they even both love to dance! Though they differ in their attitude to drinking. Newson wanted to provide whatever alcoholic drink was usual for the female wedding guests, but Farfrae was shocked, in true Scottish Presbyterian style ...

But what a contrast with with Henchard, whom she's only known for as a young woman, and for only a few years. During that time his attitude to her has varied from affection, to cold dislike, and now an almost obsessional love. Now she sees he has "skulked out of town", but although it is "mystifying" she knows it is in keeping with his volatile behaviour. Yes, she would now connect Henchard's leaving with Newson's arrival, and has been told about his earlier visit. It is a huge shock. But it's not necessarily proof that she knows about the wife selling. Henchard's embarrassment and shame at his lie alone, could be what she believes. And we see that at this point at least, she is reactive and does not consider Henchard's better motives, which Thomas Hardy has enumerated for us.

There are so many half truths and misunderstandings between these characters. Ah, and the caged goldfinch! A perfect symbol for all the cages the characters have trapped themselves in. I'm sure Peter will have something to say about this, as he collects instances of the trope of birds in cages in Victorian literature.

You argue this very well, but particularly after today's chapter I'm afraid I disagree that Elizabeth-Jane even knew her true parentage before this. And certainly did not know about the wife-selling. (I nearly said in answer to Claudia's query about maybe missing some textual evidence, that not to worry - there had not been any. And also how unlikely that would seem to have been, that Elizabeth-Jane still would not know ... (e.g. think of the "slip" about the colour of her hair as a baby, when Michael believed her to be his own) - but then this novel is full of well-kept secrets.

Here's a little more of the paragraph you quoted

"from whom she had been separated half-a-dozen years, as if by death, need hardly be detailed. It was an affecting one, apart from the question of paternity. Henchard’s departure was in a moment explained. When the true facts came to be handled the difficulty of restoring her to her old belief in Newson was not so great as might have seemed likely, for Henchard’s conduct itself was a proof that those facts were true. Moreover, she had grown up under Newson’s paternal care ..."

What this describes is their assumptions about Henchard's motives in leaving Casterbridge. But as we learn in today' s chapter 44, they are much more complex. And in fact Henchard makes great efforts to return as a "humble old friend" and fantasises about being accepted as an elderly man, treated affectionately and living with them in their home. (Though this seems a bit of a stretch to me! I think he would not feel this way for long).

It is another assumption that they would want to:

"discredit Henchard" In fact we learn in ch 44 that Newson has no malice towards Henchard, and says it was a "good joke" so although we might feel that they would naturally be tempted to "tell the truth about ALL of it" this is not what we are told has happened.

(For the record, I too find Newson's attitude unfathomable! It's passed off as being "like a good many rovers and sojourners among strange men and strange moralities", but I'm not sure this is a believable justification really.)

Even Elizabeth-Jane herself is not clear about what happened:

"you have deceived me so—so bitterly deceived me! You persuaded me that my father was not my father—allowed me to live on in ignorance of the truth for years; and then when he, my warm-hearted real father, came to find me, cruelly sent him away with a wicked invention of my death, which nearly broke his heart."

It is evident that she has now been told her true parentage, but not about the wife-selling. Since she is in a rare passion, wouldn't she have added this accusation in disgust?

On the other hand, Henchard assumes that she does know:

"Then you know all;"

and moreover keeps his own counsel. Hardy enumerates 3 things he could have said in his defence:

1. He himself had initially believed her to be his daughter, until Susan revealed the truth by letter. (I personally think that he did not protest his innocence at this point, because it would have laid the blame on her mother, and he did not wish Elizabeth-Jane - whom we are told he now truly loves - to receive this further blow.)

2. The lie he told to Newson was "the last desperate throw of a gamester" - we read at the time that it was the impulse of a moment, which he never expected to get away with, and again his rash gamble with Fate was because he "loved her affection better than his own honour".

3. "he did not sufficiently value himself" to argue his own case.

Henchard is a broken man. Partly because of his own feelings of guilt, but also perhaps because he believes Elizabeth-Jane "knows all" and he cannot believe that she would not as a consequence despise him for auctioning her mother like a piece of cattle.

But does she? It's ambiguous.

Someone asked how old Elizabeth-Jane is. She was 18 at the start, and has only been in Casterbridge for 3 years or so I think - 4 at the most. We could probably count the seasons, as the novel is based around the farming year. Including the months when they were travelling, she and Newson had been apart for 6 years (she told Henchard she was 12 when they came to England from Canada in ch 10, and its confirmed in this quotation. Also in ch 10, she says: "Father was lost last Spring".)

Therefore Elizabeth-Jane must still be in her early 20s. She had a loving, light-hearted father for almost 12 years, and had chosen a husband very like him in manner - they even both love to dance! Though they differ in their attitude to drinking. Newson wanted to provide whatever alcoholic drink was usual for the female wedding guests, but Farfrae was shocked, in true Scottish Presbyterian style ...

But what a contrast with with Henchard, whom she's only known for as a young woman, and for only a few years. During that time his attitude to her has varied from affection, to cold dislike, and now an almost obsessional love. Now she sees he has "skulked out of town", but although it is "mystifying" she knows it is in keeping with his volatile behaviour. Yes, she would now connect Henchard's leaving with Newson's arrival, and has been told about his earlier visit. It is a huge shock. But it's not necessarily proof that she knows about the wife selling. Henchard's embarrassment and shame at his lie alone, could be what she believes. And we see that at this point at least, she is reactive and does not consider Henchard's better motives, which Thomas Hardy has enumerated for us.

There are so many half truths and misunderstandings between these characters. Ah, and the caged goldfinch! A perfect symbol for all the cages the characters have trapped themselves in. I'm sure Peter will have something to say about this, as he collects instances of the trope of birds in cages in Victorian literature.

Claudia has rightly identified how important the "Casterbridge to Budmouth" road is to this novel, just as "the Ring" is. Critical meetings and walks at dramatic parts of the story occur at those sites.

Thomas Hardy was well aware of its history and the emotional power this area has; ancient history mixed with superstition. Only today I came across this piece on the Rural Histories FB site:

"In 2009, a mass Viking grave containing 54 decapitated skeletons was discovered by archaeologists on the South Dorset Ridgeway, located in the hills between Dorchester ("Casterbridge") and Weymouth ("Budmouth"), England." (Using a spoiler now just to save space)

(view spoiler)

Thomas Hardy was well aware of its history and the emotional power this area has; ancient history mixed with superstition. Only today I came across this piece on the Rural Histories FB site:

"In 2009, a mass Viking grave containing 54 decapitated skeletons was discovered by archaeologists on the South Dorset Ridgeway, located in the hills between Dorchester ("Casterbridge") and Weymouth ("Budmouth"), England." (Using a spoiler now just to save space)

(view spoiler)

Kathleen wrote: "Bridget, thank you so much for the details on both versions. I really appreciate this, as I have the newer version, and have to say--I much prefer the original!

Kathleen wrote: "Bridget, thank you so much for the details on both versions. I really appreciate this, as I have the newer version, and have to say--I much prefer the original! I find Elizabeth Jane's thoughts a..."

I agree with Kathleen's thoughts. Henchard has been punished often by his own actions, but on a wedding day, I expected Elizabeth-Jane to explain things better to her father, to reach out to understand. Its an added punishment for the man.

My book had the first version Bridget described but I think the original really was better. The break is clean — if not less painful — for both Henchard and Elizabeth-Jane.

But I love Jean's explanation about whether Elizabeth-Jane really knows the wife-swapping and assume that Newson told her about her true paternity. This is the painful part because today, so many times there are parents and step parents, we don't really think about he more traditional relationships. I believe that if Henchard has stayed, it would not have been smooth for any of them.

Bionic Jean wrote: "I'm afraid I disagree that Elizabeth-Jane even knew her true parentage before this. And certainly did not know about the wife-selling...."

Bionic Jean wrote: "I'm afraid I disagree that Elizabeth-Jane even knew her true parentage before this. And certainly did not know about the wife-selling...."I see your point, Jean, and agree about the story of Henchard selling his wife and daughter. Maybe I phrased it poorly, but I didn't think Elizabeth-Jane knew about her parentage previously. I just thought that the text implied that the full story, both of her parentage and how Newson met Susan, had been shared with her after she was reunited with Newson. After reading this chapter, though, I do think that Henchard's action of selling Susan is something that Elizabeth-Jane would have taxed Henchard with during their confrontation, especially as she is giving him reasons for refusing the relationship.

I also did not mean that they were talking trash about Henchard (LOL)! When I used the word discredit, I meant they were trying to discredit his claim of being her father--nothing more. Newson clearly had no harsh words for Henchard, and if anyone had the right, it was him.

Sorry--I don't think my syntax was as clear as it should have been.

Bridget Thank you for your kind comments. The ‘reading’ of an illustration is part association, part finding patterns, and a really big part of personal feelings. It is, like most enjoyable activities, simply one that gives a person pleasure.

Bridget Thank you for your kind comments. The ‘reading’ of an illustration is part association, part finding patterns, and a really big part of personal feelings. It is, like most enjoyable activities, simply one that gives a person pleasure.I think your linking of the chapter 19 illustration with this chapter’s image very perceptive. In both we see Henchard and Elizabeth-Jane in a room. In both illustrations their emotions are running high. You are right. The is a clear symmetry in the illustrations.

Your insight into how Henchard’s raised hand suggests he is protecting himself from Elizabeth’s words is spot on.

Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many different people and situations. Henchard’s action of selling his wife and child at the beginning of the novel set off a tsunami of events, most of which can be seen as confining people, not freeing them. Over and over in the novel a person’s decision leads them to become more entrapped within their life rather than freeing them because of their actions. Henchard’s life devolves into a series of bad choices that entrap him rather than free him.

Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many different people and situations. Henchard’s action of selling his wife and child at the beginning of the novel set off a tsunami of events, most of which can be seen as confining people, not freeing them. Over and over in the novel a person’s decision leads them to become more entrapped within their life rather than freeing them because of their actions. Henchard’s life devolves into a series of bad choices that entrap him rather than free him. I think it possible to say that as Hardy continually demonstrates that our lives are ruled by fate rather than our ability to act with free will, humans are trapped, caged, and entangled by events we cannot control. Our fate is to suffer; our fate is to not have control over our lives. The goldfinch has been captured in a small cage. Henchard carries the bird in its cage towards Elizabeth-Jane in the hope he will be able to set himself free. Henchard, I think, is carrying his own fate, as do so many other characters in the novel. The bird dies. The Gods have had their sport.

Why a goldfinch? Well, I think the key is the word gold. Gold is wealth, is value, is prestige, is the coin that will open all doors, all possibilities. But, in the end, gold holds no value. Perhaps like Midas in a way? The goldfinch died in its cage.

The poem, "On A Discovered Curl Of Hair," has been posted.

The poem, "On A Discovered Curl Of Hair," has been posted.https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

Just a reminder:

Saturday, August 23rd, is a free day.

Sunday, August 24th, is a discussion day for Chapter 45.

Peter wrote: "Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many differen..."

Peter wrote: "Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many differen..."Great interpretation, Peter!

Peter wrote: "I think it possible to say that as Hardy continually demonstrates that our lives are ruled by fate rather than our ability to act with free will, humans are trapped, caged, and entangled by events we cannot control. Our fate is to suffer; our fate is to not have control over our lives."

Peter wrote: "I think it possible to say that as Hardy continually demonstrates that our lives are ruled by fate rather than our ability to act with free will, humans are trapped, caged, and entangled by events we cannot control. Our fate is to suffer; our fate is to not have control over our lives."I agree with Claudia, and think this is wonderful analysis, Peter. This entire read has made me think about fate. I've always felt a sympathy with Hardy's view, but perhaps it matters whether you trust fate or not. It seemed to me that Elizabeth Jane trusted fate--not that she thought it would make things go her way, but that she committed to working with it, whereas Henchard was always fighting it. I think this is the major lesson for me in this novel!

Peter wrote: "Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many differen..."

Peter wrote: "Jean You have an excellent memory. Yes, my endless search for the various meanings of birds, birds in cages et al. I’m still at it. In this instance I think the caged bird represents many differen..."Peter, thanks for your excellent analysis of Henchard's bird in a cage. We'll be reading a poem about the subject next week. It's fascinating how other people can put someone in a cage, but we can also put ourselves in a cage. But I'll save more thoughts for the poem.

Bridget and Jean, your information about Maiden Castle was fascinating. It gives me an eerie feeling that Henchard was spying on Elizabeth-Jean, Farfrae, and Newsom by hiding in the elevated prehistoric fort like a soldier looking for the approach of an enemy.

Bridget and Jean, your information about Maiden Castle was fascinating. It gives me an eerie feeling that Henchard was spying on Elizabeth-Jean, Farfrae, and Newsom by hiding in the elevated prehistoric fort like a soldier looking for the approach of an enemy.

Peter wrote: "Henchard carries the bird in its cage towards Elizabeth-Jane in the hope he will be able to set himself free ..."

Wow Peter! I think this is one of the best and most insightful posts you have written, thank you!

Cindy - Please don't worry! These are subtle nuances we are talking about, and it's hard to make sure we have conveyed exactly what we meant. I know I find this! So it made me knuckle down and analyse exactly what we had been told in the text so far, and what was skimmed over.

In fact it seems we concurred about the interpretation of most of it. 🙂Then as we saw, the next chapter gave us more information about Elizabeth-Jane's feelings and "is something that Elizabeth-Jane would have taxed Henchard with during their confrontation".

I wonder whether she ever will learn this particular secret, (about the auction of her mother) or if it will continue to be fudged so we are never sure! It doesn't help that we virtually have 2 authors at some points. Nor that Hardy himself made so many revisions 🤔

Wow Peter! I think this is one of the best and most insightful posts you have written, thank you!

Cindy - Please don't worry! These are subtle nuances we are talking about, and it's hard to make sure we have conveyed exactly what we meant. I know I find this! So it made me knuckle down and analyse exactly what we had been told in the text so far, and what was skimmed over.

In fact it seems we concurred about the interpretation of most of it. 🙂Then as we saw, the next chapter gave us more information about Elizabeth-Jane's feelings and "is something that Elizabeth-Jane would have taxed Henchard with during their confrontation".

I wonder whether she ever will learn this particular secret, (about the auction of her mother) or if it will continue to be fudged so we are never sure! It doesn't help that we virtually have 2 authors at some points. Nor that Hardy himself made so many revisions 🤔

I hope everyone got to enjoy the poem, "On A Discovered Curl Of Hair", lead by Connie. Personally, I'm enjoying the mix of poems with this story. Poems were so important to Hardy, and Connie is doing a fabulous job leading us. I've added a link to the poem in the first message of this thread.

Jean wondered yesterday if Elizabeth will ever learn about the auction of her mother, or if it will all be subtle and we readers may never know. Well, if we have any chance of knowing it will be with the next chapter, which is our last. Off we go to that now.

Jean wondered yesterday if Elizabeth will ever learn about the auction of her mother, or if it will all be subtle and we readers may never know. Well, if we have any chance of knowing it will be with the next chapter, which is our last. Off we go to that now.

CHAPTER 45 - Summary

Newson, remains in Casterbridge for a while after the wedding, but misses the sea and eventually settles in Budmouth, as a more desirable residence near the sea. Elizabeth-Jane happily surveys her new home and approximately one week after her wedding, as she discovers a birdcage with a dead goldfinch in it. Why it's there remains a mystery for about a month when a servant tells Elizabeth-Jane they now know it had been brought to the wedding and forgotten by “that farmer’s man”.

Realizing that the bird had been a gift from Henchard causes Elizabeth-Jane to reflect and to wish to make her peace with him. Elizabeth-Jane tells Farfrae that she wishes to find Henchard, but when he cannot be found, Elizabeth-Jane remembers that he once considered suicide and worries what may have happened to him.

Eventually, they hear a report from someone who saw Henchard on foot, and they take the gig to drive in that direction. They spend the day searching Egdon Heath, and as they are planning to turn around for the day, they see Abel Whittle.

Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae follow Abel Whittle to a cottage. When they enter the cottage, they find Abel deeply saddened. He reports that Mr. Henchard has died just before their arrival. Henchard, Abel says, was kind to his mother, and supported the poor woman, even though he was rough on Abel for his tardiness. Abel explains that he saw Henchard leaving Casterbridge after the wedding and he followed him. Henchard grew weak and sick on the road and Abel brought him to the abandoned cottage and cared for him.

Abel shows Elizabeth-Jane and Farfrae a will that Henchard produced before he died. The will does not describe any inheritance, as Henchard owned nothing by the end of his life, but asks that Elizabeth-Jane not be told of his death, and that no funeral with mourners be held for him, and that no one remember him.

Elizabeth-Jane is moved by Henchard’s bitterness in his will and regrets her unkindness at their last meeting. For a long while, her regrets about her relationship with her stepfather are painful. But eventually the happiness and tranquility of her adult and married life prevail. She had suffered in her youth, and so, in her secure adulthood, must consider herself fortunate, despite having grown up viewing life as moments of happiness among more extended periods of pain.

Newson, remains in Casterbridge for a while after the wedding, but misses the sea and eventually settles in Budmouth, as a more desirable residence near the sea. Elizabeth-Jane happily surveys her new home and approximately one week after her wedding, as she discovers a birdcage with a dead goldfinch in it. Why it's there remains a mystery for about a month when a servant tells Elizabeth-Jane they now know it had been brought to the wedding and forgotten by “that farmer’s man”.