Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist - Group Read 5

>

Oliver Twist: Chapters 44 - 53

message 52:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 15, 2023 09:52AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Nancy is in a different psychological position from any other female character we have ever read about, in any group read. Does anyone recognise what we now call "Stockholm syndrome" in Nancy?

I should say that among all female characters I met in Dickens's novels up to now, but also outside of them, she is a unique character, more deeply developed than other ladies like her. (I have not read novels by Emile Zola, beyond L'Assommoir, to be able to talk more wisely of them.)

I should say that among all female characters I met in Dickens's novels up to now, but also outside of them, she is a unique character, more deeply developed than other ladies like her. (I have not read novels by Emile Zola, beyond L'Assommoir, to be able to talk more wisely of them.)The one I think of who is more similar to Nancy is Eponine Thénardier, who is more nuanced than her sister and more famous mother.

She would definitely be described today as suffering that Stockholm syndrome - Dickens describes her behaviour very exactly and those among us who have experienced working with groups of ill-treated women can only confirm all this.

What a darkly atmospheric chapter! It definitely felt like all of the pieces are beginning to fall into place.

What a darkly atmospheric chapter! It definitely felt like all of the pieces are beginning to fall into place.Jean, I loved it when you brought out "A small detail I liked, was the way Dickens hid the names of Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie until the end of the chapter. He was to incorporate this mystery element even better in later novels, but the kernel of it is is all here.". I thought the same thing and had to read the part several times when Dickens wrote "...a man in the garments of a countryman came up close" to realize that Dickens was talking about Noah Claypole. I had forgotten he was still dressed like a country bumpkin.

I am very frightened for Nancy, as I wonder if Claypole will lie about Nancy and tell him that Nancy was going to betray him (Fagin).

If Fagin fears that Monk is going to get caught and fears that Monk will betray him, will Fagin force Nancy to kill Monk before the "mysterious strangers" get to Monk first?

Noah overheard Oliver's name discussed. When he reports this fact to Fagin, will Fagin try to nab Oliver again?

So many questions! So many scenarios that could take place that threaten Nancy and Oliver!

And who is Monk, and how does Mr. Brownlow know him?

The tension builds!

Dickens was very much a writer for the people; what he used spoke readily to the common reader and not just the highly educated. It's great that we have so much help here for things we aren't familiar with due to time and geography. Some of these things are timeless, though, and you can see people much like his characters in real life even though there are variations in settings and where these people can be found. No more work houses, thankfully.

Dickens was very much a writer for the people; what he used spoke readily to the common reader and not just the highly educated. It's great that we have so much help here for things we aren't familiar with due to time and geography. Some of these things are timeless, though, and you can see people much like his characters in real life even though there are variations in settings and where these people can be found. No more work houses, thankfully.@ Petra That's a very good point you have about wondering if Charlotte is being set up to be a prostitute.

It seems that Mr Brownlow must know Mr Monks pretty well to be able to recognize him fairly quickly from Nancy’s description. I sensed the mention of what sounded like a seizure meant a lot to him.

It seems that Mr Brownlow must know Mr Monks pretty well to be able to recognize him fairly quickly from Nancy’s description. I sensed the mention of what sounded like a seizure meant a lot to him.

When I am reading Dickens, I always feel as if I am in London, physically there. The details are so precise and I can imagine how it would have felt reading this if you were a Londoner and familiar with every one of the places he cites.

When I am reading Dickens, I always feel as if I am in London, physically there. The details are so precise and I can imagine how it would have felt reading this if you were a Londoner and familiar with every one of the places he cites.I am another who is so grateful to see the illustration of Nancy that finally answers to my own imagination's rendering.

When Brownlow reacted to the description of Monk by filling in the scar/burn mark, I was happy. Because no matter what happens from here, Brownlow knows who the man is that he is seeking, and that is not all he knows about him, obviously.

What a dark chapter! Everyone on the "good" side is now in danger. Fagin will be able to put the bits & pieces together from what Noah has overheard.

What a dark chapter! Everyone on the "good" side is now in danger. Fagin will be able to put the bits & pieces together from what Noah has overheard. I'm curious about how Mr. Brownlow knows Monk. He recognized him from the seizures and birthmark on his neck. Interesting development. I doubt if Mr. Brownlow is the father in this family saga, so how does he fit in? I'm looking forward to reading on.

Jean, no worries. I may fall behind at times but I don't read ahead. I like participating in the discussions without knowing more than your summaries.

Oh.....I have added Nancy's Steps to my London Wish List as well.

Oh.....I have added Nancy's Steps to my London Wish List as well. @Karin: I hope Charlotte is smart enough to get herself out of this nest of darkness before it's too late. She's not mentioned a lot and I worry about her. She's putting her life into Noah's hands and that's not a good place for her to be, especially now that Noah is in Fagin's hands.

Karin and Petra: I share your concerns for Charlotte, but since she has stolen the money and given herself over to Noah, I am convinced she is beyond any rescue. She is a good illustration of how fast a woman could fall into being lost in this society.

Karin and Petra: I share your concerns for Charlotte, but since she has stolen the money and given herself over to Noah, I am convinced she is beyond any rescue. She is a good illustration of how fast a woman could fall into being lost in this society.

I would feel a lot more sympathy for Charlotte if she hadn't been beating on Oliver earlier in the book.

I would feel a lot more sympathy for Charlotte if she hadn't been beating on Oliver earlier in the book.

Katy wrote: "I would feel a lot more sympathy for Charlotte if she hadn't been beating on Oliver earlier in the book."

Katy wrote: "I would feel a lot more sympathy for Charlotte if she hadn't been beating on Oliver earlier in the book."True, but then it brings me to wonder how she was raised and/or how much of it is because she was enamoured with Noah.

Sara wrote: "Karin and Petra: I share your concerns for Charlotte, but since she has stolen the money and given herself over to Noah, I am convinced she is beyond any rescue. She is a good illustration of how f..."

Sara wrote: "Karin and Petra: I share your concerns for Charlotte, but since she has stolen the money and given herself over to Noah, I am convinced she is beyond any rescue. She is a good illustration of how f..."I agree with you, Sara. Charlotte has not been a victim in this story. She was cruel to Oliver, and as you say, she stole money from the Sowerberrys, and she showed no remorse for it. Charlotte has no moral compass, and I cannot see her changing her ways. Her character is totally different from Nancy, who has exhibited strength, compassion, loyalty and integrity. It's hard to feel sorry for Charlotte.

Petra wrote: "I'm curious about how Mr. Brownlow knows Monk. He recognized him from the seizures and birthmark on his neck..."

Petra wrote: "I'm curious about how Mr. Brownlow knows Monk. He recognized him from the seizures and birthmark on his neck..."When Mr. Brownlow described the mark upon Monk's throat as "A broad red mark, like a burn or scald?", my first thought was that this sounded like a rope burn. I wondered if Monk had survived being hung. A little far-fetched probably, but that was my immediate reaction.

Shirley, it never occurred to me that the mark on Monks might be rope marks. Creepy! That would be a surprising reveal.

Shirley, it never occurred to me that the mark on Monks might be rope marks. Creepy! That would be a surprising reveal. Charlotte hasn't been a victim yet in this story. But she's what.....15-17 years old?! That's an age where one can follow one's heart, even if it goes against one's morals, if one hasn't got anyone to lean on for guidance.

I guess I like to think of young folks as redeemable, so my hopes are that Charlotte gets out of this awful world she's put herself in. It may be an unrealistic thought, I know.

I have to say, I agree with Sara, Katy and Shirley about Charlotte. We aren't defined by our upbringing and circumstances as much as we are by our choices. Nancy tries to make good ones, to the extent that she can; Charlotte makes consistently bad ones, and never really aroused any great sympathy in me, even as a kid.

I have to say, I agree with Sara, Katy and Shirley about Charlotte. We aren't defined by our upbringing and circumstances as much as we are by our choices. Nancy tries to make good ones, to the extent that she can; Charlotte makes consistently bad ones, and never really aroused any great sympathy in me, even as a kid.

Sara, Shirley, Katy, Werner, I suppose you are correct. Charlotte hasn't shown any signs of empathy or feeling (except for Noah). It's really a shame that some people go down this dark road. I look for the redemption and turn-around, but some people won't take that path. Charlotte might be (and probably is) one of these.

Sara, Shirley, Katy, Werner, I suppose you are correct. Charlotte hasn't shown any signs of empathy or feeling (except for Noah). It's really a shame that some people go down this dark road. I look for the redemption and turn-around, but some people won't take that path. Charlotte might be (and probably is) one of these.

Charlotte is a very interesting character, for sure. I can't stop thinking about that scene many chapters back where she was feeding Noah oysters (a known aphrodisiac at the time), while the Sowerberrys were gone, and she was alone with Noah. Dickens is painting her as a bit promiscuous. Like Petra, I was worried Fagin's gang would turn her into a prostitute, and even though she was horrible to Oliver, I think that would be a terrible fate for her.

Charlotte is a very interesting character, for sure. I can't stop thinking about that scene many chapters back where she was feeding Noah oysters (a known aphrodisiac at the time), while the Sowerberrys were gone, and she was alone with Noah. Dickens is painting her as a bit promiscuous. Like Petra, I was worried Fagin's gang would turn her into a prostitute, and even though she was horrible to Oliver, I think that would be a terrible fate for her.It was Nancy that caught my heart in this chapter. Mr. Brownlow offers her a way out three times, and she refuses each time. That was painful to read. Thank you Jean for labelling it Stockholm Syndrome, my goodness that's exactly what it is.

Thank you also for the details about the history of the London Bridge and the link to the Southwark Cathedral. I explored their website and read about their history. Fascinating stuff! I leanred that Geoffrey Chaucer starts the The Canterbury Tales at that church. They also mention our favorite, Charles Dickens as part of their history, which made me smile.

message 72:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 16, 2023 03:05PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

I have a guide book from Southwark Cathedral, but am not sure where my photos are! 🙄 It is truly beautiful though.

One thing about London is that you can turn a corner and find yourself in a completely different area. So from a rundown residential area (or foul slums of dilapidated rat-infested builings, in Charles Dickens's time) you might then find yourself in the City, where all the financial transactions take place; turn another few corners and you may find a bustling area of shops, or an attractive park, or an area of gracious living in a wealthy district. They all run side by side.

One thing about London is that you can turn a corner and find yourself in a completely different area. So from a rundown residential area (or foul slums of dilapidated rat-infested builings, in Charles Dickens's time) you might then find yourself in the City, where all the financial transactions take place; turn another few corners and you may find a bustling area of shops, or an attractive park, or an area of gracious living in a wealthy district. They all run side by side.

Bridget wrote: "It was Nancy that caught my heart in this chapter. Mr. Brownlow offers her a way out three times, and she refuses each time..."

Bridget wrote: "It was Nancy that caught my heart in this chapter. Mr. Brownlow offers her a way out three times, and she refuses each time..."Oh, Bridget... I did not catch this, but you are right. As Dickens uses references from the Bible so many times, the point you made gives me great hope for Nancy. In Matthew 26, when Jesus was being offered up to be crucified, the Apostle Peter denied knowing Christ 3 times before sunrise ("before the cock crowed"). The Bible says that "Peter went outside and wept bitterly."

After Nancy turns down Brownlow's offer three times, Dickens says she "vented the anguish of her heart in bitter tears." Just as Peter was redeemed and "found joy in the morning", hopefully Dickens is hinting to his readers that Nancy will also find redemption and joy. I hope so. I truly love this character.

Shirley (stampartiste) wrote: " the Apostle Peter denied knowing Christ 3 times before sunrise ("before the cock crowed"). The Bible says that "Peter went outside and wept bitterly."

After Nancy turns down Brownlow's offer three times, Dickens says she "vented the anguish of her heart in bitter tears."..."

Shirley - this interpretation is inspired! I love it.

After Nancy turns down Brownlow's offer three times, Dickens says she "vented the anguish of her heart in bitter tears."..."

Shirley - this interpretation is inspired! I love it.

message 75:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 03:53AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

This next installment is one of the most momentous, thrilling and hair-raising ones Charles Dickens ever wrote. The writing is superb, but brace yourselves ... chapter 47 is not an easy read!

message 76:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 04:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Chapter 47:

“Fatal Consequences …”

It is “the dead of night; when the streets are silent and deserted; [and] even sounds appear to slumber.”

Fagin sits brooding and plotting with a pale distorted face, and red, blood-shot eyes, looking:

“less like a man, than like some hideous phantom, moist from the grave, and worried by an evil spirit … His right hand was raised to his lips, and as, absorbed in thought, he hit his long black nails, he disclosed among his toothless gums a few such fangs as should have been a dog’s or rat’s.”

His thoughts are in turmoil. Mortified that his plans have come to nothing, and that he has not had his revenge on Sikes, he is filled with hatred and distrust of Nancy. Fagin fears:

“detection, and ruin, and death; and a fierce and deadly rage kindled by all;”

Bolter (Noah Calypole) is lying asleep alongside, when Sikes enters with the loot from his latest burglary. Fagin looks so wild that Sikes is momentarily frightened, but Fagin cannot speak. Eventually he comes to what he wants to say gradually. He asks what Sikes would do if Bolter “peached” on them:

“not grabbed, trapped, tried, earwigged by the parson and brought to it on bread and water,—but of his own fancy”

Fagin’s eyes flash with rage as he suggests he himself “peaching” on Sikes, or if Charley, or the Dodger, or Bet would, working himself up into a frenzy. Sikes says he would kill any and all that turned against him, very impatient at all the questioning. Fagin switches tack. He looks at the sleeping Bolter, with ”devilish anticipation”, and says very deliberately and meaningfully:

“He’s tired—tired with watching for her so long,—watching for her, Bill.”

He wakes Bolter and questions him making him explain what he observed when Nancy met two people on the bridge at midnight. Bolter recounts the conversation and how Nancy was asked to give up her friends, especially Monks. Bolter then continues and tells how Nancy had earlier given Sikes a drink of laudanum so she could meet with Rose secretly.

Upon hearing this Sikes loses his temper completely:

“Hell’s fire!” cried Sikes, breaking fiercely from the Jew. “Let me go!”

Flinging the old man from him, he rushed from the room, and darted, wildly and furiously, up the stairs.“

Fagin manages to stop him before he can get out; they both have a fire in their eyes. He urges:

“not too violent for safety. Be crafty, Bill, and not too bold.”

Bill Sikes in a high state of tension, singleminded in his fury, makes his way home to confront Nancy. As he enters, Nancy is sleeping and wakes with pleasure to see it is Bill Sikes. But she soon realises what has happened, and as he grabs her by the throat, begs him:

“spare my life for the love of Heaven, as I spared yours … stop before you spill my blood! I have been true to you, upon my guilty soul I have!”

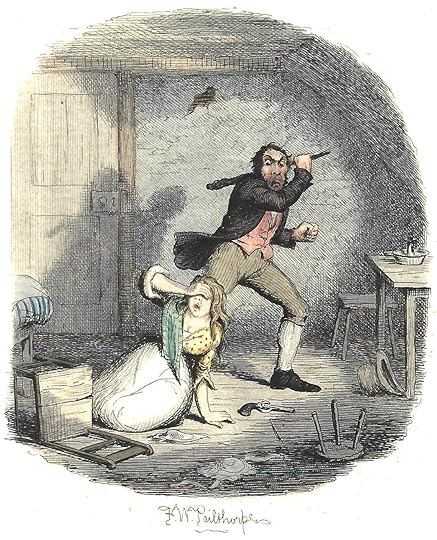

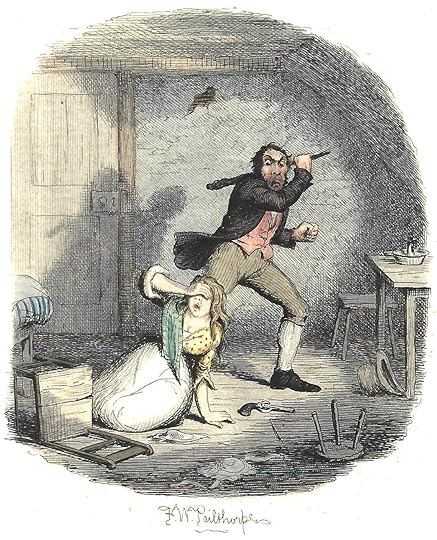

"A foul deed" - Frederic W. Pailthorpe 1886

She begs him to leave this dreadful place, and for them both to start again, far apart, and lead better lives saying: “It is never too late to repent.”

But Bill Sikes does not take in the fact that Nancy didn’t betray him, and he wants nothing of this. Infuriated as he is, he only thinks that a shot might make too much noise so he beats his pistol:

“twice with all the force he could summon, upon the upturned face that almost touched his own.”

Nancy is nearly blinded by the blood from the blow to her face, but holds Rose Maylie’s handkerchief as high as she can praying to God for mercy.

“It was a ghastly figure to look upon. The murderer staggering backward to the wall, and shutting out the sight with his hand, seized a heavy club and struck her down.”

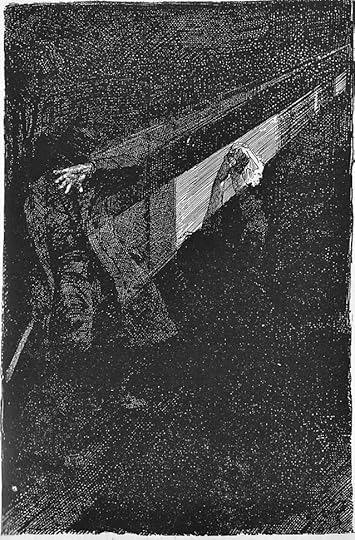

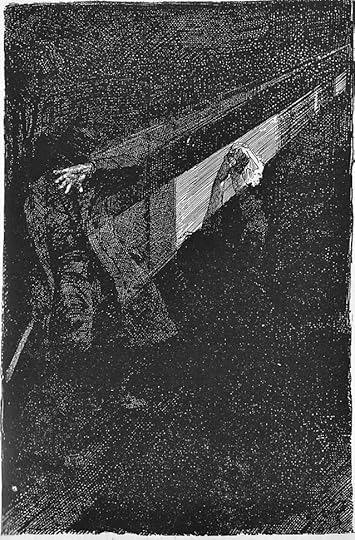

"The Death of Nancy" - Harry Furniss 1910

“Fatal Consequences …”

It is “the dead of night; when the streets are silent and deserted; [and] even sounds appear to slumber.”

Fagin sits brooding and plotting with a pale distorted face, and red, blood-shot eyes, looking:

“less like a man, than like some hideous phantom, moist from the grave, and worried by an evil spirit … His right hand was raised to his lips, and as, absorbed in thought, he hit his long black nails, he disclosed among his toothless gums a few such fangs as should have been a dog’s or rat’s.”

His thoughts are in turmoil. Mortified that his plans have come to nothing, and that he has not had his revenge on Sikes, he is filled with hatred and distrust of Nancy. Fagin fears:

“detection, and ruin, and death; and a fierce and deadly rage kindled by all;”

Bolter (Noah Calypole) is lying asleep alongside, when Sikes enters with the loot from his latest burglary. Fagin looks so wild that Sikes is momentarily frightened, but Fagin cannot speak. Eventually he comes to what he wants to say gradually. He asks what Sikes would do if Bolter “peached” on them:

“not grabbed, trapped, tried, earwigged by the parson and brought to it on bread and water,—but of his own fancy”

Fagin’s eyes flash with rage as he suggests he himself “peaching” on Sikes, or if Charley, or the Dodger, or Bet would, working himself up into a frenzy. Sikes says he would kill any and all that turned against him, very impatient at all the questioning. Fagin switches tack. He looks at the sleeping Bolter, with ”devilish anticipation”, and says very deliberately and meaningfully:

“He’s tired—tired with watching for her so long,—watching for her, Bill.”

He wakes Bolter and questions him making him explain what he observed when Nancy met two people on the bridge at midnight. Bolter recounts the conversation and how Nancy was asked to give up her friends, especially Monks. Bolter then continues and tells how Nancy had earlier given Sikes a drink of laudanum so she could meet with Rose secretly.

Upon hearing this Sikes loses his temper completely:

“Hell’s fire!” cried Sikes, breaking fiercely from the Jew. “Let me go!”

Flinging the old man from him, he rushed from the room, and darted, wildly and furiously, up the stairs.“

Fagin manages to stop him before he can get out; they both have a fire in their eyes. He urges:

“not too violent for safety. Be crafty, Bill, and not too bold.”

Bill Sikes in a high state of tension, singleminded in his fury, makes his way home to confront Nancy. As he enters, Nancy is sleeping and wakes with pleasure to see it is Bill Sikes. But she soon realises what has happened, and as he grabs her by the throat, begs him:

“spare my life for the love of Heaven, as I spared yours … stop before you spill my blood! I have been true to you, upon my guilty soul I have!”

"A foul deed" - Frederic W. Pailthorpe 1886

She begs him to leave this dreadful place, and for them both to start again, far apart, and lead better lives saying: “It is never too late to repent.”

But Bill Sikes does not take in the fact that Nancy didn’t betray him, and he wants nothing of this. Infuriated as he is, he only thinks that a shot might make too much noise so he beats his pistol:

“twice with all the force he could summon, upon the upturned face that almost touched his own.”

Nancy is nearly blinded by the blood from the blow to her face, but holds Rose Maylie’s handkerchief as high as she can praying to God for mercy.

“It was a ghastly figure to look upon. The murderer staggering backward to the wall, and shutting out the sight with his hand, seized a heavy club and struck her down.”

"The Death of Nancy" - Harry Furniss 1910

message 77:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 04:18AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Please pause for a moment … or take whatever time you need. Our worst nightmare has come true, and Nancy has sacrificed herself for Oliver.

message 78:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 04:27AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Just as most illustrators chickened out of illustrating this episode, I quailed at the thought of writing a summary, but have done my best.

This is one of the ghastliest and most powerful chapters Charles Dickens ever wrote, even somehow exceeding the riots and executions in his historical novels. It’s so detailed and person to person. For me, the claustrophobic domestic setting, and our knowledge of Nancy’s innocence, makes it almost unbearable to read.

The hints of forecasting in yesterday’s chapter continue here with phrases like “hot grease falling down in clots upon the table”: the word clots is so suggestive of blood. “Wrapped in a torn coverlet” is suggestive of a burial shroud, and Fagin’s “toothless gums” and fangs reduce him to the state of an animal. The earlier parts of the chapter all build up to this final horror.

Fagin has deliberately led Sikes to believe that Nancy has agreed to inform on them; there is no mention of Nancy’s insistence on not betraying Bill Sikes. But we know that that is not what she said—nor what Noah had reported to him. This is such powerful dramatic irony, as at various stages, we know something that the character does not, and we could see that it might lead to a tragic end—which indeed it now has.

This is one of the ghastliest and most powerful chapters Charles Dickens ever wrote, even somehow exceeding the riots and executions in his historical novels. It’s so detailed and person to person. For me, the claustrophobic domestic setting, and our knowledge of Nancy’s innocence, makes it almost unbearable to read.

The hints of forecasting in yesterday’s chapter continue here with phrases like “hot grease falling down in clots upon the table”: the word clots is so suggestive of blood. “Wrapped in a torn coverlet” is suggestive of a burial shroud, and Fagin’s “toothless gums” and fangs reduce him to the state of an animal. The earlier parts of the chapter all build up to this final horror.

Fagin has deliberately led Sikes to believe that Nancy has agreed to inform on them; there is no mention of Nancy’s insistence on not betraying Bill Sikes. But we know that that is not what she said—nor what Noah had reported to him. This is such powerful dramatic irony, as at various stages, we know something that the character does not, and we could see that it might lead to a tragic end—which indeed it now has.

message 79:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 04:47AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

By the way, it is now safe to google about the 1831 "London Bridge" sent to Lake Havasu City in Arizona, and also about "Nancy’s Steps" in London.

There is an urban myth that in Charles Dickens's novel, Nancy was killed on those steps, (probably because the character was, in the musical “Oliver!”) For years there was a blue plaque there which actually said so! The plaque has now been removed, but even if I’d said that it did not happen in the book, as we have all now read, it might still have been enough to reveal that Nancy would be murdered.

Here is a good article with historic film and stills of the bridge in situ:

https://www.golakehavasu.com/london-b...

There is an urban myth that in Charles Dickens's novel, Nancy was killed on those steps, (probably because the character was, in the musical “Oliver!”) For years there was a blue plaque there which actually said so! The plaque has now been removed, but even if I’d said that it did not happen in the book, as we have all now read, it might still have been enough to reveal that Nancy would be murdered.

Here is a good article with historic film and stills of the bridge in situ:

https://www.golakehavasu.com/london-b...

message 80:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 04:52AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Bill had told Nancy that he knows what she said, and she of course knows that she refused to give them up and answers him based on that knowledge. She cannot know what Fagin has told Bill, but the reader knows that Fagin has misled him and it was he who deliberately placed Nancy’s life in jeopardy.

When Fagin warned Bill Sikes not to be too violent for safety, I think Charles Dickens may have intended readers to think he meant not to go too far i.e. he hoped Sikes would knock Nancy around a bit, but not actually kill her. But even if he did mean this, the “safety” he is so concerned about is that of the gang, and not Nancy’s personal safety. It would serve him very well if she were no longer around. So Bill’s thought about a gun making too much noise is probably precisely the sort of thing that Fagin had in mind.

I don’t really know who is the more loathsome; Fagin the evil mastermind, with his devious cunning, or Bill Sikes with his brutality. We can’t get away from the fact that Sikes did this, but Fagin planned it all; surely he is culpable too?

When Fagin warned Bill Sikes not to be too violent for safety, I think Charles Dickens may have intended readers to think he meant not to go too far i.e. he hoped Sikes would knock Nancy around a bit, but not actually kill her. But even if he did mean this, the “safety” he is so concerned about is that of the gang, and not Nancy’s personal safety. It would serve him very well if she were no longer around. So Bill’s thought about a gun making too much noise is probably precisely the sort of thing that Fagin had in mind.

I don’t really know who is the more loathsome; Fagin the evil mastermind, with his devious cunning, or Bill Sikes with his brutality. We can’t get away from the fact that Sikes did this, but Fagin planned it all; surely he is culpable too?

message 81:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 05:06AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Angelic Light?

We were given indicators of this in the first paragraph, about the “radiant glory” of the sun, shedding an equal ray both through a cathdral dome and a rotten crevice. This decribes the sun’s light, but there is a subtle subtext.

One detail stands out as perhaps an indicator of what Sikes may feel, and which we learn more of tomorrow. When he is struck by the light from the window, Sikes seems to realise what he has done, and cannot bear to face the eyes of the dead Nancy. Harry Furniss bravely tries to capture this in his illustration, in which Sikes’s hand is prominent, blocking out the stream of light.

Nancy of course reaches up to heaven, right until the last moment. Because of Charles Dickens's sincere Christian beliefs, I think he is indicating here (and later) that the light of heaven is angelic light, and that Nancy, although dying a brutal death so young, has been saved by God for a “better life to come”. Shirley picked up the biblical references relating to Peter the apostle, and although the Holy Bible says he survived after Christ to proselytise Christianity, he was crucified in the end. So he sacrificed himself too, just as Nancy has for the personification of innocence, Oliver.

Charles Dickens went on to portray a heavenly light in many of his novels at key moments, and even light playing round good characters’ heads. It is often written as light from a window, but is clearly intended as a sort of halo. His readers would be used to such symbolism in Victorian religious texts, and would know this very well.

I know some will take issue with this; it may not accord with your personal beliefs—and it certainly does not accord with our hopes for Nancy’s future on this Earth! Many of his readers would be be in floods of tears reading this harrowing chapter. But as with mesmerism, this kind of spirituality is what Charles Dickens himself believed. So just as with his commitment to mesmerism, we need to read his words with his personal beliefs in mind.

Also, there is the very important point that dramatically, Nancy had to die. This was to consolidate Charles Dickens’s message about social conditions; in this case he highlighted the dire circumstances of young girls who become prostitutes as a last resort, and not through their own choice. Charles Dickens really engaged people emotionally, through a convincing and sympathetic portrayal of one such young girl, brought up without hope among thieves, fences and prostitutes. When Nancy thought she would end up drowned in the river Thames, that was a very real fear. Many poor women with no means of support threw themselves in the river to end their lives. Charles Dickens used to visit the city mortuary, and saw the bodies. He bears witness to this in several works, where a character will think of, or may actually do, this.

But the end of Nancy’s story is unique in his canon, and you will remember how Charles Dickens had to defend it in his later Prefaces to the novel, saying “IT IS TRUE” (his own block capitals). And how did Charles Dickens himself cope with what he had written? I’ll write about that in the next post.

We were given indicators of this in the first paragraph, about the “radiant glory” of the sun, shedding an equal ray both through a cathdral dome and a rotten crevice. This decribes the sun’s light, but there is a subtle subtext.

One detail stands out as perhaps an indicator of what Sikes may feel, and which we learn more of tomorrow. When he is struck by the light from the window, Sikes seems to realise what he has done, and cannot bear to face the eyes of the dead Nancy. Harry Furniss bravely tries to capture this in his illustration, in which Sikes’s hand is prominent, blocking out the stream of light.

Nancy of course reaches up to heaven, right until the last moment. Because of Charles Dickens's sincere Christian beliefs, I think he is indicating here (and later) that the light of heaven is angelic light, and that Nancy, although dying a brutal death so young, has been saved by God for a “better life to come”. Shirley picked up the biblical references relating to Peter the apostle, and although the Holy Bible says he survived after Christ to proselytise Christianity, he was crucified in the end. So he sacrificed himself too, just as Nancy has for the personification of innocence, Oliver.

Charles Dickens went on to portray a heavenly light in many of his novels at key moments, and even light playing round good characters’ heads. It is often written as light from a window, but is clearly intended as a sort of halo. His readers would be used to such symbolism in Victorian religious texts, and would know this very well.

I know some will take issue with this; it may not accord with your personal beliefs—and it certainly does not accord with our hopes for Nancy’s future on this Earth! Many of his readers would be be in floods of tears reading this harrowing chapter. But as with mesmerism, this kind of spirituality is what Charles Dickens himself believed. So just as with his commitment to mesmerism, we need to read his words with his personal beliefs in mind.

Also, there is the very important point that dramatically, Nancy had to die. This was to consolidate Charles Dickens’s message about social conditions; in this case he highlighted the dire circumstances of young girls who become prostitutes as a last resort, and not through their own choice. Charles Dickens really engaged people emotionally, through a convincing and sympathetic portrayal of one such young girl, brought up without hope among thieves, fences and prostitutes. When Nancy thought she would end up drowned in the river Thames, that was a very real fear. Many poor women with no means of support threw themselves in the river to end their lives. Charles Dickens used to visit the city mortuary, and saw the bodies. He bears witness to this in several works, where a character will think of, or may actually do, this.

But the end of Nancy’s story is unique in his canon, and you will remember how Charles Dickens had to defend it in his later Prefaces to the novel, saying “IT IS TRUE” (his own block capitals). And how did Charles Dickens himself cope with what he had written? I’ll write about that in the next post.

message 82:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 05:18AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

I’ll put the title of this one after a couple of sentences for now, in case it comes through in my notifications and people read it before they have read the chapter. I’ll delete this part later. There, that should be enough, so ...

The Murder of Nancy

We are probably still trembling at the scene, and wonder how Charles Dickens could have written such a brutal end for a character he clearly admired and liked a lot. In fact the scene haunted him, all his days. It’s no exaggeration to say that the murder of Nancy in this first real novel by Charles Dickens, was one of the main contributing factors in his premature death. It killed him too. But we need to go back a bit …

In December 1853, Charles Dickens gave his first public readings, in Birmingham. A series of three for charity, they were rapturously received:

“They lost nothing,” he reported after a performance of A Christmas Carol: “misinterpreted nothing, followed everything closely, laughed and cried … and animated me to the extent that I felt as if we were all bodily going up into the clouds together.”

Charles Dickens’s talent and exhibitionism, his histrionic flair, mesmeric powers and expressiveness evoked tears, applause, shrieks, laughter, hisses, and shouts of “Hear, hear!” from his audiences. He was to tour incessantly, compulsively, on both sides of the Atlantic for the last fifteen years of his life, and for 4 years practically abandoned his writing in favour of these highly emotional, theatrical performances.

Initially Charles Dickens had been concerned that what came to known as “Sikes and Nancy” might strike audiences as “so horrible” that they would be frightened away from future readings altogether. He said:

“I have no doubt that I could perfectly petrify an audience by carrying out the notion I have of the way of rendering it”. For 30 years he had known this was emotional dynamite. He had written to John Forster just after writing this scene:

“Nancy is no more. I showed what I have done to Kate last night, who was in an unspeakable ”state“: from which and my own impressions I auger well.”

But he was not to know how much the scene would preoccupy his thoughts, until in 1869 he decided he would include it in his public readings. Contemporary newspapers and magazines recorded that the killing of Nancy evoked horror, screams, and that members of the audience fainted from sheer terror, not only of the words, but the theatrical and manic way Charles Dickens delivered them. Of one perfomance he wrote that it was:

“… By far the best murder yet done. We had a contagion of fainting, and yet the place was not hot. I should think we had a dozen or twenty ladies taken out stiff and rigid at various times.”

Charles Dickens threw himself into the performance with such ferocity that audiences gaped at him with fixed expressions of horror. Crowds milled around, becoming increasingly hysterical. He acted both parts, from a special reading script he had written, and he threw himself into both roles; both the terrified victim Nancy, and the vicious hounded brute Sikes.

Sometimes Charles Dickens enacted “Sikes and Nancy” four times a week. Whenever he gave public readings his pulse rose higher, but now his doctors noted that after reading this scene, his pulse rose dangerously high. Afterwards he walked through the streets, still living the roles, obssessed and convinced that someone or something was following him. During his final tour the doctors and his friends begged him to stop, for the sake of his health, but Charles Dickens was adamant - and driven.

“Sikes and Nancy” was what his audiences wanted; his most popular and acclaimed performance. But a few months later, on 9th June 1870, Charles Dickens was dead, of an apparent stroke, at the early age of 58. He had such a strong sense of belief in his work, and so much still left to do, that his death was unexpected and remains deeply shocking.

The Murder of Nancy

We are probably still trembling at the scene, and wonder how Charles Dickens could have written such a brutal end for a character he clearly admired and liked a lot. In fact the scene haunted him, all his days. It’s no exaggeration to say that the murder of Nancy in this first real novel by Charles Dickens, was one of the main contributing factors in his premature death. It killed him too. But we need to go back a bit …

In December 1853, Charles Dickens gave his first public readings, in Birmingham. A series of three for charity, they were rapturously received:

“They lost nothing,” he reported after a performance of A Christmas Carol: “misinterpreted nothing, followed everything closely, laughed and cried … and animated me to the extent that I felt as if we were all bodily going up into the clouds together.”

Charles Dickens’s talent and exhibitionism, his histrionic flair, mesmeric powers and expressiveness evoked tears, applause, shrieks, laughter, hisses, and shouts of “Hear, hear!” from his audiences. He was to tour incessantly, compulsively, on both sides of the Atlantic for the last fifteen years of his life, and for 4 years practically abandoned his writing in favour of these highly emotional, theatrical performances.

Initially Charles Dickens had been concerned that what came to known as “Sikes and Nancy” might strike audiences as “so horrible” that they would be frightened away from future readings altogether. He said:

“I have no doubt that I could perfectly petrify an audience by carrying out the notion I have of the way of rendering it”. For 30 years he had known this was emotional dynamite. He had written to John Forster just after writing this scene:

“Nancy is no more. I showed what I have done to Kate last night, who was in an unspeakable ”state“: from which and my own impressions I auger well.”

But he was not to know how much the scene would preoccupy his thoughts, until in 1869 he decided he would include it in his public readings. Contemporary newspapers and magazines recorded that the killing of Nancy evoked horror, screams, and that members of the audience fainted from sheer terror, not only of the words, but the theatrical and manic way Charles Dickens delivered them. Of one perfomance he wrote that it was:

“… By far the best murder yet done. We had a contagion of fainting, and yet the place was not hot. I should think we had a dozen or twenty ladies taken out stiff and rigid at various times.”

Charles Dickens threw himself into the performance with such ferocity that audiences gaped at him with fixed expressions of horror. Crowds milled around, becoming increasingly hysterical. He acted both parts, from a special reading script he had written, and he threw himself into both roles; both the terrified victim Nancy, and the vicious hounded brute Sikes.

Sometimes Charles Dickens enacted “Sikes and Nancy” four times a week. Whenever he gave public readings his pulse rose higher, but now his doctors noted that after reading this scene, his pulse rose dangerously high. Afterwards he walked through the streets, still living the roles, obssessed and convinced that someone or something was following him. During his final tour the doctors and his friends begged him to stop, for the sake of his health, but Charles Dickens was adamant - and driven.

“Sikes and Nancy” was what his audiences wanted; his most popular and acclaimed performance. But a few months later, on 9th June 1870, Charles Dickens was dead, of an apparent stroke, at the early age of 58. He had such a strong sense of belief in his work, and so much still left to do, that his death was unexpected and remains deeply shocking.

I admit to being emotionally spent when I reached the end of this chapter. The feeling of horror and inescapable doom just permeated everything, every word.

I admit to being emotionally spent when I reached the end of this chapter. The feeling of horror and inescapable doom just permeated everything, every word. Having read this before (long ago), this was the one scene that stayed with me completely. What I had lost over those years, though, was the horrible participation by Fagin. I think movies and musicals have softened him over the years, and it was gut-wrenching to sit across the table from him and witness the unfeeling, unremorseful way in which he sent Nancy to what he knew was sure death. Sikes had many times expressed a willingness to kill her for much smaller offences, and Fagin begins by saying "if a person did this what would you do?" building him into a frenzy before releasing him on the poor girl. Nancy literally dies for love--love of Sikes which tied her and kept her there, and a love of the innocence of Oliver that she did not want to see destroyed.

The story about Dickens and the performances is almost as sad as this chapter, Jean. I doubt anyone, with the exception of Van Gogh, ever gave more of himself to his art. At least Dickens got the money and recognition in his lifetime.

Jean, The story of the London Bridge going to Lake Havasu is fascinating. My nephew and his family just moved there. This is another reason to go visit them!

Jean, The story of the London Bridge going to Lake Havasu is fascinating. My nephew and his family just moved there. This is another reason to go visit them!The scene of Nancy's death is certainly the most dramatic of any of his novels in my memory. Like you said, this one was so personal and one on one and we also don't expect such a good person to die violently "on camera" so to speak with the details.

If she had been only found dead, it wouldn't have had the same impact. Nancy thoroughly captured my heart which made the whole scene so devastating.

I did remember this part but had even more anxiety knowing that it would happen! I can certainly understand how Dickens' blood pressure went up every time he read it.

I love the religious imagery - thank you Jean and Shirley!

Now we read on hoping to see that Fagan, Sikes and Noah get their just deserts.

I wonder if Nancy's end is why the Artful Dodger is sent away and Noah is brought in? Could it be that Dickens didn't want the Artful Dodger sullied (by association) with this vicious act?

Marvelous observation, Sue. I'm not sure The Artful Dodger wouldn't have tried to warn Nancy or save her. You almost have to have a disinterested party, like Noah, to have this come off the way it did. Of course, Fagin couldn't have used Dodger because Nancy would have recognized him and known she was being followed.

Marvelous observation, Sue. I'm not sure The Artful Dodger wouldn't have tried to warn Nancy or save her. You almost have to have a disinterested party, like Noah, to have this come off the way it did. Of course, Fagin couldn't have used Dodger because Nancy would have recognized him and known she was being followed.

Sara wrote: "Marvelous observation, Sue. I'm not sure The Artful Dodger wouldn't have tried to warn Nancy or save her. You almost have to have a disinterested party, like Noah, to have this come off the way it ..."

Sara wrote: "Marvelous observation, Sue. I'm not sure The Artful Dodger wouldn't have tried to warn Nancy or save her. You almost have to have a disinterested party, like Noah, to have this come off the way it ..."Sara, I agree that Nancy would have recognized him. Also, even if he remained as part of the active gang, it seems he would have had to take violent action against Sikes and Fagin,

I missed your post before, probably because I had started typing and got interrupted by my Dogs and came back. You are so right about how Fagin whipped Sikes into a frenzy. Fagin is even worse than Sikes because he manipulates everyone to be their worst selves. I'm glad that Dicken's didn't let it be that Fagin caused Nancy to murder Sikes.

Jean, your summary was beautifully written. I can imagine it was difficult! And the background is fascinating--about the bridge but even more, about the ultimate sacrifice Dickens made, a sacrifice similar to Nancy's.

Jean, your summary was beautifully written. I can imagine it was difficult! And the background is fascinating--about the bridge but even more, about the ultimate sacrifice Dickens made, a sacrifice similar to Nancy's.A harrowing chapter indeed. It seemed strange to me how quickly Fagin believed Noah, and didn't maybe question Nancy before he sicced Sikes on her. Fagin is really the most at fault, in my view. Sikes was a crime of passion, whereas Fagin sat calmly hatching this evil plan.

Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature. Only now does Dickens clarify a handkerchief was the keepsake Rose gave to Nancy as they parted from the clandestine meeting on London Bridge. Dickens adds the adjective "white" to describe the handkerchief. White probably symbolizes the innocence and purity of the bearer and the giver. Perhaps as with Catholics praying to saints for intercession, Nancy is using the handkerchief as a type of intercession with Rose acting as the role of a living saint or angelic figure. In other words, the handkerchief could be seen as a secular version of a Catholic relic; a material object, for example, a bone or article of clothing, associated with a saint. As with venerating a relic offers escaping the punishment for sins in the afterlife, Nancy appears to be using the handkerchief for the same purpose.

Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature. Only now does Dickens clarify a handkerchief was the keepsake Rose gave to Nancy as they parted from the clandestine meeting on London Bridge. Dickens adds the adjective "white" to describe the handkerchief. White probably symbolizes the innocence and purity of the bearer and the giver. Perhaps as with Catholics praying to saints for intercession, Nancy is using the handkerchief as a type of intercession with Rose acting as the role of a living saint or angelic figure. In other words, the handkerchief could be seen as a secular version of a Catholic relic; a material object, for example, a bone or article of clothing, associated with a saint. As with venerating a relic offers escaping the punishment for sins in the afterlife, Nancy appears to be using the handkerchief for the same purpose.Probably the handkerchief was the only gift Nancy has ever received in her life. Handkerchiefs have been featured in the novel as mundane items to be stolen and sold. Now a handkerchief has been elevated to a powerful symbolic role.

Michael wrote: "Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature. Only now does Dickens reveal a handkerchief was the keepsak..."

Michael wrote: "Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature. Only now does Dickens reveal a handkerchief was the keepsak..."Love your Observations, Michael! The handkerchief symbolism blew by me (heehee). Your comments make me want to read it again. There are so many intricacies packed into this wonderful novel.

I have finished the book today, I had to, tomorrow I am leaving for my vacations (to Cornwall!!) and I cannot bring books with me, only my kindle.

I have finished the book today, I had to, tomorrow I am leaving for my vacations (to Cornwall!!) and I cannot bring books with me, only my kindle.I know that I have been a silent reader and I have not contributed to the comments, but I have been reading them every day and they have enhanced enormously my pleasure in reading this book. I will keep on reading them in the next days.

It is a consolation to me that you found Nancy's death as appalling as I did. My heart broke. I could never be a writer, I could never write a scene like that.

I had read about Dickens' performances of Sikes killing Nancy in a biographical article a few years ago, and even that did not prepare me emotionally for this brutal scene. I would think that an author would become very emotionally attached to a favorite character like Nancy. I don't know how Dickens acted the two parts, night after night, killing a character so dear to him. Dickens did not just read the parts, but he used his acting ability to make it seem more real. Is it any wonder that people in the audience were fainting, and Dickens blood pressure was sky high?

I had read about Dickens' performances of Sikes killing Nancy in a biographical article a few years ago, and even that did not prepare me emotionally for this brutal scene. I would think that an author would become very emotionally attached to a favorite character like Nancy. I don't know how Dickens acted the two parts, night after night, killing a character so dear to him. Dickens did not just read the parts, but he used his acting ability to make it seem more real. Is it any wonder that people in the audience were fainting, and Dickens blood pressure was sky high?

I am so blown away by these last few chapters and how Dickens has built up the dread and the feeling of foreboding that something terrible is about to happen. I kept thinking he wouldn’t describe the murder in such detail, as Sue mentioned already, but only Dickens can do the scene to its credit. I now have to think of Nancy as a martyr. Not one who died for her religion but for her belief in innocence and preserving that in Oliver. She will always hold that mindset in my mind now. It’s difficult to get past gopher death, but its acceptance is what provides the full meaning of her sacrifice. Just like Jean said, Nancy had to die.

I am so blown away by these last few chapters and how Dickens has built up the dread and the feeling of foreboding that something terrible is about to happen. I kept thinking he wouldn’t describe the murder in such detail, as Sue mentioned already, but only Dickens can do the scene to its credit. I now have to think of Nancy as a martyr. Not one who died for her religion but for her belief in innocence and preserving that in Oliver. She will always hold that mindset in my mind now. It’s difficult to get past gopher death, but its acceptance is what provides the full meaning of her sacrifice. Just like Jean said, Nancy had to die.

Daniella! I'm so happy you returned and delighted that you enjoyed the novel and our comments so much. Thank you.

"I could never write a scene like that" - Oh yes Nancy ... she had to die, but then as you'll have read, Charles Dickens couldn't accept it either 😥

Enjoy Cornwall! Charles Dickens was to visit it 4 years after writing Oliver Twist, (off-topic) (view spoiler)

"I could never write a scene like that" - Oh yes Nancy ... she had to die, but then as you'll have read, Charles Dickens couldn't accept it either 😥

Enjoy Cornwall! Charles Dickens was to visit it 4 years after writing Oliver Twist, (off-topic) (view spoiler)

message 95:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 11:17AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Excellent post, thank you Michael! 😊

If you have not read it, you might enjoy John O. Jordan's essay "The Purloined Handkerchief" which is reprinted in the Norton Critical Edition. He has written several scholarly books about Charles Dickens (follow the link for details).

If you have not read it, you might enjoy John O. Jordan's essay "The Purloined Handkerchief" which is reprinted in the Norton Critical Edition. He has written several scholarly books about Charles Dickens (follow the link for details).

I go all green with envy when anyone mentions being in Cornwall. Have a wonderful time, Daniela. Try to fit in as many of those wonderful places Dickens went as you can!

I go all green with envy when anyone mentions being in Cornwall. Have a wonderful time, Daniela. Try to fit in as many of those wonderful places Dickens went as you can!Up to this chapter, I have been pulling at my own reins to keep from going ahead. Now I feel like someone stuck a pin in me and I need recovery time before I can tackle the next chapter. If I had been reading this straight through, I'm positive I would have closed it here for breath.

message 97:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 18, 2023 02:55PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

I too am finding this installment tremendously full-on! We can tell Charles Dickens is almost singlemindedly focused on his conclusion, and showing us the motivations and drive of the characters involved.

But also, in a way, we can tell that he has done with Richard Bentley! In the previous month he was beavering away at Oliver Twist, determined to finish it and publish his 3 volumes before his contract expired there, and wow, what a powerful conclusion we are now reading! Richard Bentley must have been kicking himself that he let such a talented author and editor get away.

But also, in a way, we can tell that he has done with Richard Bentley! In the previous month he was beavering away at Oliver Twist, determined to finish it and publish his 3 volumes before his contract expired there, and wow, what a powerful conclusion we are now reading! Richard Bentley must have been kicking himself that he let such a talented author and editor get away.

For some reason, even though I have never read this book or seen the films, etc, I have “always” known that Nancy dies, is killed by Sikes. Someone must have said this in my hearing a long time ago and it stuck. With that in my mind, what struck me the most in this chapter was the absolute craven evil of Fagin. The physical description of him waiting for Sikes is the portrait of a devil, a satyr, leading another man to commit his murder. Sikes is brutal and mean but not the scheming evil the Fagin is.

For some reason, even though I have never read this book or seen the films, etc, I have “always” known that Nancy dies, is killed by Sikes. Someone must have said this in my hearing a long time ago and it stuck. With that in my mind, what struck me the most in this chapter was the absolute craven evil of Fagin. The physical description of him waiting for Sikes is the portrait of a devil, a satyr, leading another man to commit his murder. Sikes is brutal and mean but not the scheming evil the Fagin is.

I am an absolute wreck after finishing this chapter. Like Sara, I had to put the book down. (Actually, I put it in a drawer to be out of sight while I have a good cry.)

I am an absolute wreck after finishing this chapter. Like Sara, I had to put the book down. (Actually, I put it in a drawer to be out of sight while I have a good cry.)Loved Michael’s comment about the handkerchiefs in the novel. And I thought Jean’s description of the murder scene being claustrophobic was spot on. When Sikes pushes the heavy table against the door my heart dropped and I knew there was no escape. I like Pailthorpe’s illustration, but I wish he had drawn the table turned over and blocking the door.

I keep thinking about Nancy sleeping peacefully and half dressed only to perish moments later. I thought I remembered reading this novel, but now I’m sure I haven’t. Like Sue, I knew Nancy was going to die, but I thought she was shot. This is so much more potent. So intimate

I also love the comments regarding the handkerchiefs, and agree that the intimacy and the cruel suffering that is inflicted on Nancy by knowing he is going to kill her and then being beaten is what makes this so horrific. Had Dickens killed her off-stage, we would have lamented, but I don't think we would have felt it in the way we do!

I also love the comments regarding the handkerchiefs, and agree that the intimacy and the cruel suffering that is inflicted on Nancy by knowing he is going to kill her and then being beaten is what makes this so horrific. Had Dickens killed her off-stage, we would have lamented, but I don't think we would have felt it in the way we do!

Books mentioned in this topic

London Labour and the London Poor (other topics)Oliver Twist (other topics)

Oliver Twist (other topics)

Mary Barton (other topics)

Caledonian Road (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Henry Mayhew (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Andrew O Hagan (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...

Charles Dickens includes bridges in all his novels: they are symbols of eventful meeting places and portentous change. But we know that he wants us to recognise this one, detailing it most precisesly so that despite all the contenders, it's possible to identify it even now that it is no longer there. (I spent quite a long time researching this! The London Encyclopedia is a huge comprehensive book for all such historical questions of location.)

This part is rooted in reality, as well as London Bridge being a metaphor, just as the river Thames represents a life force, and also a character (nice point there, Claudia!)