The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Wuthering Heights

Wuthering Heights

>

Wuthering Heights, Chp. 01-07

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I thought the first two chapters were hilarious.

I thought the first two chapters were hilarious. "Did he invite you for tea?"

"No, he just invited me over."

"Then you can't have any."

It's like Lockwood went visiting the Munsters or the Addams family, and Lurch answered the door.

Xan wrote: "I thought the first two chapters were hilarious."

Xan wrote: "I thought the first two chapters were hilarious."The second-hand embarrassment was real!

He seemed a sullen, patient child; hardened, perhaps, to ill-treatment ... This endurance made old Earnshaw furious when he discovered his son persecuting the poor, fatherless child, as he called him.

He seemed a sullen, patient child; hardened, perhaps, to ill-treatment ... This endurance made old Earnshaw furious when he discovered his son persecuting the poor, fatherless child, as he called him.Methinks the gentleman doth protest too much. Old Earnshaw certainly put a lot of effort in bringing Heathcliff home with him, and the favouritism was pronounced.

I love the mystery of it all!

For me the secondhand embarrassment went two ways. On the one hand: imagine being as inhospitable, and uncaring about what happens to your neighbour and tenant, setting the dogs on him etc. On the other hand it was very clear that Mr. Lockwood was not exactly ... how shall I put it ... knowing when he was not welcome, or seeing his neighbours as real people with cares, lives etc. of their own. He went there kind of expecting to be catered to and entertained, because he was bored, even if he could have known at least Heathcliff and Joseph would be too busy and not willing to entertain him exactly. The whole welp, actions have consequences, and he should have thought about those consequences before he set off to be entertained where he was not welcome, when it would be dangerous to get back.

My take is: up to this point, none of the characters are actually nice. And honestly, I love good, hateable characters like these.

My take is: up to this point, none of the characters are actually nice. And honestly, I love good, hateable characters like these.

I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on, but I don't feel for any of them at the moment. A group of curmudgeons living together. What could be more just? The one thing missing is a ring from Hell to imprison them in. I envision Dante and Virgil paying them a visit.

I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on, but I don't feel for any of them at the moment. A group of curmudgeons living together. What could be more just? The one thing missing is a ring from Hell to imprison them in. I envision Dante and Virgil paying them a visit. And then there is Lockwood living alone in what has to be a giant of a house. Plenty of room for ghosts.

Xan wrote: "I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on."

Xan wrote: "I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on."I have a feeling it will, Xan.

Jantine, I agree that Lockwood was a bit clueless, but setting Wolf and Gnasher on him? 🤣

When I started reading Wuthering Heights, and then also read Tristram’s comments about the structure of the novel, I was reminded of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

When I started reading Wuthering Heights, and then also read Tristram’s comments about the structure of the novel, I was reminded of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It seems to me that both Brontë and Shelley employed this roundabout narrative structure in their stories. Others have to tell the story? An author within an author? It is as if they pushed themselves, as the true authors, to the furthest reaches. As to the reason why, I do not know.

Xan wrote: "I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on, but I don't feel for any of them at the moment. A group of curmudgeons living together. What could be more just? The one thing missing is a ring from..."

Xan wrote: "I'm sure my attitude will change as we read on, but I don't feel for any of them at the moment. A group of curmudgeons living together. What could be more just? The one thing missing is a ring from..."A group of curmudgeons aptly describes these characters.

I enjoyed this description of Wuthering Heights:

I enjoyed this description of Wuthering Heights:Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there, at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind, blowing over the edge, by the excessive slant of a few, stunted firs at the end of the house; and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun. Happily, the architect had foresight to build it strong: the narrow windows are deeply set in the wall, and the corners defended with large jutting stones.

Tristram wrote: "Who is Heathcliff? Where did Mr. Earnshaw first meet him, and why did he decide to take him home with him, where there are already two children of his own? Is there a connection between Earnshaw and Heathcliff? Will we ever get to know?

Tristram wrote: "Who is Heathcliff? Where did Mr. Earnshaw first meet him, and why did he decide to take him home with him, where there are already two children of his own? Is there a connection between Earnshaw and Heathcliff? Will we ever get to know?"

Why did Earnshaw go to Liverpool? IIRC, he was rather vague as to the reasons. When he returns home, he pulls Heathcliff out of his coat, like he's another gift or possession, and the other gifts are damaged. Maybe Heathcliff is too?

And as to Hindley and Heathcliff getting along, well, if you have a dog who is your sole dog, and then you bring home another one, they don't get along. Often one has to go. And we know that between man and canine, canine is the far superior species. So who's surprised that Hindley marks his territory?

Xan wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Who is Heathcliff? Where did Mr. Earnshaw first meet him, and why did he decide to take him home with him, where there are already two children of his own? Is there a connection be..."

It clearly does not bode well for social serenity at Wuthering Heights that Mr. Earnshaw lost the whip when looking after Heathcliff and broke the fiddle into the bargain. So the first association for the siblings is one of frustration. I can also understand Hindley's jealousy and hatred, at least while he is a kid - because it must be unsettling for a boy or girl to see that their father's affections go quite clearly to a newcomer.

Saying that, however, one should probably also remember that in those days there were lots of step- and foster children in households but probably also quite of lot of inner-family tensions. Imagine Hindley's frustration when by and by both Cathy and Mrs. Dean change sides.

It clearly does not bode well for social serenity at Wuthering Heights that Mr. Earnshaw lost the whip when looking after Heathcliff and broke the fiddle into the bargain. So the first association for the siblings is one of frustration. I can also understand Hindley's jealousy and hatred, at least while he is a kid - because it must be unsettling for a boy or girl to see that their father's affections go quite clearly to a newcomer.

Saying that, however, one should probably also remember that in those days there were lots of step- and foster children in households but probably also quite of lot of inner-family tensions. Imagine Hindley's frustration when by and by both Cathy and Mrs. Dean change sides.

Xan wrote: "I've decided Yorkshire is a foreign language."

Remember that Yorkshire guy from Nicholas Nickleby? He was just as bad to understand. Luckily, my edition has ample annotations on Joseph's language.

Remember that Yorkshire guy from Nicholas Nickleby? He was just as bad to understand. Luckily, my edition has ample annotations on Joseph's language.

John wrote: "I enjoyed this description of Wuthering Heights:

Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there, at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind, blowing over the edge, by the e..."

Thanks for pointing this out, John! The thick walls and the little windows seem to mirror the inner life of most of the characters - they are all, as you said, curmudgeons, and they also seem to live for themselves mostly, as you might expect from people living in a house that seems more like a stronghold.

Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there, at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind, blowing over the edge, by the e..."

Thanks for pointing this out, John! The thick walls and the little windows seem to mirror the inner life of most of the characters - they are all, as you said, curmudgeons, and they also seem to live for themselves mostly, as you might expect from people living in a house that seems more like a stronghold.

John wrote: "When I started reading Wuthering Heights, and then also read Tristram’s comments about the structure of the novel, I was reminded of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

It seems to me that both Brontë a..."

This is a good point to keep in mind for further discussion, I am sure. As far as I can judge by now, the introduction into the scene we get by Lockwood guarantees more suspense because we are given a very strange family situation at Wuthering Heights, highly volatile characters and, of course, like the first first-person narrator, we want to know what might have caused that situation. Plunging into the past is always an adventure, and doing so through the eyes of one minor character (Mrs Dean) invites us to question her perspective and to form our own theories.

The more I am thinking about this complicated narrative structure, the more it seems to me to anticipate the style of a more modern writer like Conrad.

It seems to me that both Brontë a..."

This is a good point to keep in mind for further discussion, I am sure. As far as I can judge by now, the introduction into the scene we get by Lockwood guarantees more suspense because we are given a very strange family situation at Wuthering Heights, highly volatile characters and, of course, like the first first-person narrator, we want to know what might have caused that situation. Plunging into the past is always an adventure, and doing so through the eyes of one minor character (Mrs Dean) invites us to question her perspective and to form our own theories.

The more I am thinking about this complicated narrative structure, the more it seems to me to anticipate the style of a more modern writer like Conrad.

Tristram wrote: "Xan wrote: "I've decided Yorkshire is a foreign language."

Tristram wrote: "Xan wrote: "I've decided Yorkshire is a foreign language."Remember that Yorkshire guy from Nicholas Nickleby? He was just as bad to understand. Luckily, my edition has ample annotations on Joseph..."

Yes. Part of the reason I said that. Nicholas Nickleby, or to say it in Yorkshire: 'las 'bai.

Xan wrote: "I've decided Yorkshire is a foreign language."

Xan wrote: "I've decided Yorkshire is a foreign language."Indeed. There are scholars who refer to people who speak both a local dialect and Standard English as bilingual.

John wrote: "I enjoyed this description of Wuthering Heights:

John wrote: "I enjoyed this description of Wuthering Heights:Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there, at all times, indeed: one may guess the power of the north wind, blowing over the edge, by the excessive slant of a few, stunted firs at the end of the house; and by a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way, as if craving alms of the sun."

John, that's a wonderful description! Muriel Spark posits that the element of storm is a pronounced motif throughout the Brontë works, describing "cataclysmic events of nature as a sympathetic manifestation of some inner, personal tempest".

I have the same, Tristram. Especially since he was already described as old when Heathcliff and Cathy were young. I can imagine that he f.i. was in his thirties, and because of hard work in the open air without sunprotection and his vinegar-y demeanor he already seemed old to the children. Then twenty years later he was in his fifties, and looking even older. That's how I think it adds up with him being that 'old' while still working.

Jantine wrote: "I have the same, Tristram. Especially since he was already described as old when Heathcliff and Cathy were young. I can imagine that he f.i. was in his thirties, and because of hard work in the ope..."

In one of the later chapters we learn that Mrs. Dean is as old as Hindley, and Hindley is eight years his sister's senior. I think this is very odd because I always had the impression that Mrs. Dean played the role of a kind of surrogate mother to Catherine. Nevertheless, Bronte only made her eight years older than Cathy, and this does not convince me at all.

In one of the later chapters we learn that Mrs. Dean is as old as Hindley, and Hindley is eight years his sister's senior. I think this is very odd because I always had the impression that Mrs. Dean played the role of a kind of surrogate mother to Catherine. Nevertheless, Bronte only made her eight years older than Cathy, and this does not convince me at all.

On the other hand Mrs. Dean made some ... let's say interesting choices that imo really show how immature she actually was for the role she was given.

And she played the role of younger Catherine's surrogate mother, to the older Catherine she was more like some kind of big sister but then a servant of sorts. If she was eight years older than Catherine-the-mom, she was about 28 years older than Catherine-the-younger.

And she played the role of younger Catherine's surrogate mother, to the older Catherine she was more like some kind of big sister but then a servant of sorts. If she was eight years older than Catherine-the-mom, she was about 28 years older than Catherine-the-younger.

Maybe, I pictured her older all in all because when she is introduced into the story, she is already of an advanced age. She must also have been married sometime because now she is Mrs. Dean.

That might be, yes.

If I add things up correctly she's somewhere between 42 and 48 when Mr. Lockwood meets her.

8 when Heathcliff's Cathy was born

From what I get from the book Cathy was between 16 and 18 when she married Edgar Linton, so then she'd been 24 to 26.

Catherine was born about a year later, 25 - 27

Catherine was about 19 when Lockwood arrived - 44 - 46

I might be one or two years off there, but eh ... In our modern minds Mrs. Dean might not have been that old. And if I'm totally honest, the way she acts in these chapters and the next in her story paint her younger than she actually is. Like she tells about herself as if she is a 16-year-old trying to be older and wiser, instead of someone in her twenties.

If I add things up correctly she's somewhere between 42 and 48 when Mr. Lockwood meets her.

8 when Heathcliff's Cathy was born

From what I get from the book Cathy was between 16 and 18 when she married Edgar Linton, so then she'd been 24 to 26.

Catherine was born about a year later, 25 - 27

Catherine was about 19 when Lockwood arrived - 44 - 46

I might be one or two years off there, but eh ... In our modern minds Mrs. Dean might not have been that old. And if I'm totally honest, the way she acts in these chapters and the next in her story paint her younger than she actually is. Like she tells about herself as if she is a 16-year-old trying to be older and wiser, instead of someone in her twenties.

"Mr. Heathcliff?", I said. A nod was the answer.

Chapter 1

Artist: Thomas Davidson

1842–1919

Text Illustrated:

1801—I have just returned from a visit to my landlord—the solitary neighbour that I shall be troubled with. This is certainly a beautiful country! In all England, I do not believe that I could have fixed on a situation so completely removed from the stir of society. A perfect misanthropist’s Heaven—and Mr. Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us. A capital fellow! He little imagined how my heart warmed towards him when I beheld his black eyes withdraw so suspiciously under their brows, as I rode up, and when his fingers sheltered themselves, with a jealous resolution, still further in his waistcoat, as I announced my name.

“Mr. Heathcliff?” I said.

A nod was the answer.

“Mr. Lockwood, your new tenant, sir. I do myself the honour of calling as soon as possible after my arrival, to express the hope that I have not inconvenienced you by my perseverance in soliciting the occupation of Thrushcross Grange: I heard yesterday you had had some thoughts—”

“Thrushcross Grange is my own, sir,” he interrupted, wincing. “I should not allow any one to inconvenience me, if I could hinder it—walk in!”

The “walk in” was uttered with closed teeth, and expressed the sentiment, “Go to the Deuce!” even the gate over which he leant manifested no sympathising movement to the words; and I think that circumstance determined me to accept the invitation: I felt interested in a man who seemed more exaggeratedly reserved than myself.

When he saw my horse’s breast fairly pushing the barrier, he did put out his hand to unchain it, and then sullenly preceded me up the causeway, calling, as we entered the court,—“Joseph, take Mr. Lockwood’s horse; and bring up some wine.”

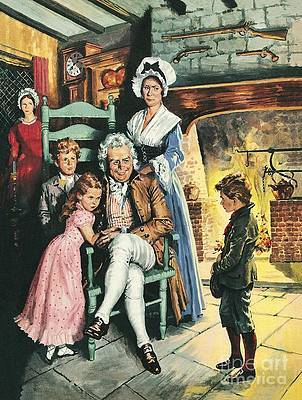

We crowded round, and over Miss Cathy’s head I had a peep at a dirty, ragged, black-haired child

Chapter 4

Artist:

Edwin Phillips

Text Illustrated:

“And at the end of it to be flighted to death!” he said, opening his great-coat, which he held bundled up in his arms. “See here, wife! I was never so beaten with anything in my life: but you must e’en take it as a gift of God; though it’s as dark almost as if it came from the devil.”

We crowded round, and over Miss Cathy’s head I had a peep at a dirty, ragged, black-haired child; big enough both to walk and talk: indeed, its face looked older than Catherine’s; yet when it was set on its feet, it only stared round, and repeated over and over again some gibberish that nobody could understand. I was frightened, and Mrs. Earnshaw was ready to fling it out of doors: she did fly up, asking how he could fashion to bring that gipsy brat into the house, when they had their own bairns to feed and fend for? What he meant to do with it, and whether he were mad? The master tried to explain the matter; but he was really half dead with fatigue, and all that I could make out, amongst her scolding, was a tale of his seeing it starving, and houseless, and as good as dumb, in the streets of Liverpool, where he picked it up and inquired for its owner. Not a soul knew to whom it belonged, he said; and his money and time being both limited, he thought it better to take it home with him at once, than run into vain expenses there: because he was determined he would not leave it as he found it. Well, the conclusion was, that my mistress grumbled herself calm; and Mr. Earnshaw told me to wash it, and give it clean things, and let it sleep with the children.

"Let me in - Let me in"

Chapter 3

Artist:

Christian Birmingham

Text Illustrated:

This time, I remembered I was lying in the oak closet, and I heard distinctly the gusty wind, and the driving of the snow; I heard, also, the fir bough repeat its teasing sound, and ascribed it to the right cause: but it annoyed me so much, that I resolved to silence it, if possible; and, I thought, I rose and endeavoured to unhasp the casement. The hook was soldered into the staple: a circumstance observed by me when awake, but forgotten. “I must stop it, nevertheless!” I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand!

The intense horror of nightmare came over me: I tried to draw back my arm, but the hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed,

“Let me in—let me in!”

“Who are you?” I asked, struggling, meanwhile, to disengage myself.

“Catherine Linton,” it replied, shiveringly (why did I think of Linton? I had read Earnshaw twenty times for Linton)—“I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!”

As it spoke, I discerned, obscurely, a child’s face looking through the window. Terror made me cruel; and, finding it useless to attempt shaking the creature off, I pulled its wrist on to the broken pane, and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bedclothes: still it wailed, “Let me in!” and maintained its tenacious gripe, almost maddening me with fear.

“How can I!” I said at length. “Let me go, if you want me to let you in!”

Text Illustrated:

The hook was soldered into the staple: a circumstance observed by me when awake, but forgotten. ‘I must stop it, nevertheless!’ I muttered, knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand!

The intense horror of nightmare came over me: I tried to draw back my arm, but the hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed, ‘Let me in—let me in!’ ‘Who are you?’ I asked, struggling, meanwhile, to disengage myself. ‘Catherine Linton,’ it replied, shiveringly (why did I think of Linton? I had read Earnshaw twenty times for Linton); ‘I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!’

The intense horror of nightmare came over me: I tried to draw back my arm, but the hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed,

“Let me in—let me in!”

“Who are you?” I asked, struggling, meanwhile, to disengage myself.

“Catherine Linton,” it replied, shiveringly (why did I think of Linton? I had read Earnshaw twenty times for Linton)—“I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!”

Artist: Fritz Eichenberg

Chapter 1

Artist: Fritz Eichenberg

Text Illustrated:

Joseph mumbled indistinctly in the depths of the cellar, but gave no intimation of ascending; so his master dived down to him, leaving me vis-à-vis the ruffianly bitch and a pair of grim shaggy sheep-dogs, who shared with her a jealous guardianship over all my movements. Not anxious to come in contact with their fangs, I sat still; but, imagining they would scarcely understand tacit insults, I unfortunately indulged in winking and making faces at the trio, and some turn of my physiognomy so irritated madam, that she suddenly broke into a fury and leapt on my knees. I flung her back, and hastened to interpose the table between us. This proceeding aroused the whole hive: half-a-dozen four-footed fiends, of various sizes and ages, issued from hidden dens to the common centre. I felt my heels and coat-laps peculiar subjects of assault; and parrying off the larger combatants as effectually as I could with the poker, I was constrained to demand, aloud, assistance from some of the household in re-establishing peace.

Mr. Heathcliff and his man climbed the cellar steps with vexatious phlegm: I don’t think they moved one second faster than usual, though the hearth was an absolute tempest of worrying and yelping. Happily, an inhabitant of the kitchen made more dispatch; a lusty dame, with tucked-up gown, bare arms, and fire-flushed cheeks, rushed into the midst of us flourishing a frying-pan: and used that weapon, and her tongue, to such purpose, that the storm subsided magically, and she only remained, heaving like a sea after a high wind, when her master entered on the scene.

“What the devil is the matter?” he asked, eyeing me in a manner that I could ill endure after this inhospitable treatment.

“What the devil, indeed!” I muttered. “The herd of possessed swine could have had no worse spirits in them than those animals of yours, sir. You might as well leave a stranger with a brood of tigers!”

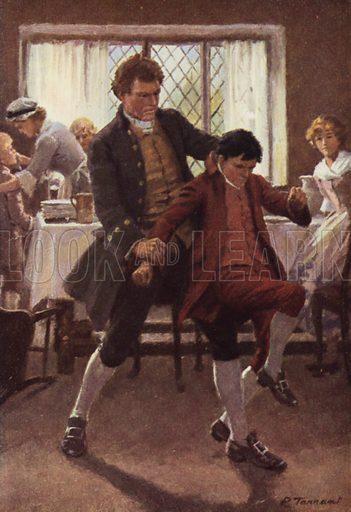

Mr. Earnshaw snatched up the culprit directly

Chapter 7

Percy Tarrant

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Earnshaw snatched up the culprit directly and conveyed him to his chamber; where, doubtless, he administered a rough remedy to cool the fit of passion, for he appeared red and breathless. His sister began weeping to go home, and Cathy stood by confounded, blushing for all.

Dear Curiosities,

I am looking forward to this re-read of Wuthering Heights because when I read it for the first time, I was probably 15 or 16 years old and I remember that I did not particularly take to the book, thinking it had way too much drama in it. Nevertheless, you never read the same book twice, and it may well be that I am going to come to a different impression of the only novel that Emily Brontë ever wrote.

This week’s reading instalment comprises Chapters 1-7, and unlike with the Dickens threads, I am not going to give detailed recaps of the plot here but try to point out some ideas and questions that we might discuss, but, of course, I take it for granted that it is understood that everyone is welcome to spark off their own discussions and share whatever ideas came to them when reading the text.

For starters, the narrative structure of the novel is quite complex in that the first three and a half chapters of given from the perspective of a Mr. Lockwood, who is fed up with society and has therefore rented a place called Thrushcross Grange on the Yorkshire moors. When he makes his courtesy call at Wuthering Heights, the place where his landlord Heathcliff lives, he is not exactly welcomed there but finds in Heathcliff a surly and forbidden man, whose daughter-in-law Catherine, meanwhile a widow, seems to be a prisoner of the place. At least, she once says that they don’t allow her to go further than the garden wall. Despite the unfriendly reception, Mr. Lockwood is curious enough to pay a second visit to Wuthering Heights, but this time he is utterly humiliated when he has to beg that he be allowed to stay there for the night, the weather getting more and more hostile, and when they practically set one of the dogs on him. The maid Zillah, the only person there to have an iota of empathy and helpfulness, hides him away in a room that was formerly inhabited by Catherine Earnshaw / Linton, and here Lockwood comes across notes made by Catherine on the margins of several books. When Heathcliff, alarmed by the noise Lockwood makes waking up from a nightmare, enters the room, he is at first shocked to find someone in Catherine’s bed, and Lockwood also notices that Catherine seems to be the one soft spot that Heathcliff has.

Back home, our narrator asks his housekeeper Ellen Dean to tell him the story about Catherine and Heathcliff, and from this moment on, our perspective is shifted to that of the servant, who goes some 22 years back in history – the novel starts, as its first word informs us, in the year 1801 –, when Heathcliff first comes to live with the Earnshaws at Wuthering Heights, an orphan that was picked up by old Mr. Earnshaw on a business journey. Heathcliff’s presence and the fact that Earnshaw has clearly taken a strong liking to the boy, disrupts the state of affairs in the family because the eldest son, Hindley, sees him as a rival, a cuckoo’s child, and a threat to his own succession to owning Wuthering Heights, whereas his sister Catherine by and by befriends the orphan. When old Mr. Earnshaw dies, Hindley, who has meanwhile married a woman named Frances, takes over and he is determined to put Heathcliff into what Hindley considers his proper place – namely as one of the servants. Catherine has struck up an acquaintance with the children of the neighbouring family, the Lintons, who own Thrushcross Grange, and apparently – this is, at least, what Heathcliff fears, she is changing her ways under the influence of the Lintons, from a wild tomboy to a refined lady.

One of the most mysterious points in this first part of the novel seems to be the origins of Heathcliff, whose very outward appearance marks him as a stranger because he is of a dark complexion, and Mr. Linton remarks that he might be “’a little Lascar – or an American or Spanish castaway.’” Very often, people at Wuthering Heights refer to him as a gipsy, and at first only Mr. Earnshaw shows a liking to him – something that Heathcliff, sullen and introverted as he is, knows to turn to his own advantage. As time goes by, though, not only Catherine, but also Mrs. Dean, relent towards Heathcliff, and the latter often tries to help Heathcliff reconcile himself with the altered situation after Mr. Earnshaw’s death.

Who is Heathcliff? Where did Mr. Earnshaw first meet him, and why did he decide to take him home with him, where there are already two children of his own? Is there a connection between Earnshaw and Heathcliff? Will we ever get to know?

The background story also deals with the two worlds Catherine can live in: On the one hand, there is the life of a country lass, a girl not much looked after and who can have her own ways in pretty much everything – a liberty she uses to befriend Heathcliff and roam the countryside with him, poking fun at the apparently pampered Linton children, especially at Edgar, who is regarded as effete and weak. In this world, Catherine clearly sympathizes with Heathcliff, who is strong, determined and daring, and she also displays similar qualities – for example she does not cry out when the Linton dog gets hold of her ankle. On the other hand, however, there are social mores and rules, especially for young girls of Catherine’s class, and these are illustrated by the Lintons, whose luxurious life may appeal to Cathy as well. After all, she stays at the place for several weeks to cure the injury caused by the dog, and when she returns to Wuthering Heights, at least her outward appearance is changed to that of a fine lady, whom Heathcliff had better not touch lest he spoils her dress.

In a way, Heathcliff is an alien to the established society at Wuthering Heights, but Cathy can also become alienated, either to Heathcliff or society, depending on her choice.

A last point that might be worth noticing is the roughness of the landscape and of the weather: The novel’s title is that of the place where the story mainly unfolds, and it is a place marked by heavy and continuous wind that seem intent on driving the humans residing there off the face of the earth. Winds, snowfalls and the landscape as well are hostile and forbidding, and Mr. Lockwood soon experiences their hostile powers, but they also seem to have left their marks in the inhabitants’ behaviour because with the possible exceptions of Zillah, and Mrs. Dean, everyone else is downright impolite and spiteful towards Lockwood. At the same time, the wind also seems to carry memories of past tragedies and losses, further enhancing the bitterness and discontent of the inhabitants.

All in all, I think that this is a promising start for a novel that will keep us busy for some weeks – a mixture of melodrama, Gothic novel even – as for instance, when the narrator thinks that there is a ghost in the wind, trying to get ingress to the chamber – and love story.