The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Great Expectations

2022 - Great Expectations

>

Great Expectations, Chp. 08-10

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I’ll give a quick recap of Chapters 9 and 10 here, which also include important moments in Pip’s life. In Chapter 9, we are told that Mrs. Joe and Mr. Pumblechook are waiting for Pip to come home and to tell them everything that went on at Miss Havisham’s. Our hero is so troubled by their incessant questions that he starts telling them blatant lies of wondrous things, such as velvet coaches, dogs eating veal-cutlets and other things. Which brings me on to a question:

What do you think of this instance of lying on the part of Pip? Does it affect, in your eyes, his reliability as a narrator?

I was asking myself this question because he tells that when Joe comes in, Mrs. Joe tells her husband everything she learned from Pip, “more for the relief of her own mind than for the gratification of his”. When reading this, it struck me that Pip could hardly know the real motives for Mrs. Joe’s communication; do we have, here at least, a sign of Pip’s interpretations of things being unfavourable to Mrs. Joe?

Later, Pip has a bad conscience about all his fibs with regard to Joe, and he makes a clean breast of it all to his friend. Joe is greatly concerned and tells him something so wise that I’m going to give it as a quotation:

Maybe, this bit of advice will become important in the course of the novel. Up in his room, Pip again is haunted by feelings of social inferiority and he cannot help thinking that Joe and his sister would be looked down upon by Estella and Miss Havisham. The chapter ends with the following words, which again show the more mature narrator commenting on his life:

Chapter 10 tells us of a meaningful encounter: When Pip one Saturday night goes to pick up Joe from the Three Jolly Bargemen, where he is smoking his pipe, he finds his friend seated at a table together with Mr. Wopsle and a stranger, who continually cocks his eye at Pip as though he were pointing an invisible gun at him. The stranger has his head all on one side – which, again, reminded me of a hanging (and of Mr. Flintwinch from Little Dorrit) – and he has tied a handkerchief around his neck, just like Pip’s convict. In the course of the conversation, the stranger asks a lot of questions as to how Pip and Joe are related, and he stirs his rum with a file – in a way that is only visible to Pip. When Joe and Pip leave, the stranger gives him some coins enveloped in paper, and to the Gargeries’ surprise they later find out that this paper is

Was it the convict who had sent Pip those two bank notes? And why are they described as “fat” and “sweltering”?

What do you think of this instance of lying on the part of Pip? Does it affect, in your eyes, his reliability as a narrator?

I was asking myself this question because he tells that when Joe comes in, Mrs. Joe tells her husband everything she learned from Pip, “more for the relief of her own mind than for the gratification of his”. When reading this, it struck me that Pip could hardly know the real motives for Mrs. Joe’s communication; do we have, here at least, a sign of Pip’s interpretations of things being unfavourable to Mrs. Joe?

Later, Pip has a bad conscience about all his fibs with regard to Joe, and he makes a clean breast of it all to his friend. Joe is greatly concerned and tells him something so wise that I’m going to give it as a quotation:

”If you can’t get to be oncommon through going straight, you’ll never get to do it through going crooked.”

Maybe, this bit of advice will become important in the course of the novel. Up in his room, Pip again is haunted by feelings of social inferiority and he cannot help thinking that Joe and his sister would be looked down upon by Estella and Miss Havisham. The chapter ends with the following words, which again show the more mature narrator commenting on his life:

”That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. But it is the same with any life. Imagine one selected day struck out of it, and think how different its course would have been. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.“

Chapter 10 tells us of a meaningful encounter: When Pip one Saturday night goes to pick up Joe from the Three Jolly Bargemen, where he is smoking his pipe, he finds his friend seated at a table together with Mr. Wopsle and a stranger, who continually cocks his eye at Pip as though he were pointing an invisible gun at him. The stranger has his head all on one side – which, again, reminded me of a hanging (and of Mr. Flintwinch from Little Dorrit) – and he has tied a handkerchief around his neck, just like Pip’s convict. In the course of the conversation, the stranger asks a lot of questions as to how Pip and Joe are related, and he stirs his rum with a file – in a way that is only visible to Pip. When Joe and Pip leave, the stranger gives him some coins enveloped in paper, and to the Gargeries’ surprise they later find out that this paper is

”[n]othing less than two fat sweltering one-pound notes that seemed to have been on terms of the warmest intimacy with all the cattle-markets in the county.”

Was it the convict who had sent Pip those two bank notes? And why are they described as “fat” and “sweltering”?

Some comments about chapter 8.

Some comments about chapter 8.Estella may be very pretty and very proud, and she may look down on Pip for being a commoner, but every so often she lets something like this out when telling Pumblechook he cannot meet Miss Havisham: “but you see she don’t."

Now I don't think a young, educated lady, not of the commoner class, would talk like that, not even in early 19th century. It's a barbarism, and I don't think educated Brits would talk this way. So, who is Estella, really? What is her background?

-------------------------------

What am I missing about the 14? and 16? What's that about?

--------------------------------

Pip's first impression of Miss Havisham and her room is one of wax (preservation) and decay. That's an interesting combination, and I think its apt. She's standing still in time, the time being twenty to nine on some fateful day. Yet time waits for no one, and even the preserved decay as it passes on.

------------------------------------

Estella affects Pip greatly. He focuses on her disdain, yet he's attracted to her. She's pretty and like no one else his age. This is why I think he's at least 12 years old here. If he were younger, say about 8, he would more likely shove her for what she says than be awe struck by her looks and attitude. I also think this is where his distain for his roots take root. He has good reason not to like most people around him. Now he has words to put to his feelings -- "common," "coarse," "thick."

Poor Pip. So far in his life he has encountered just a few female characters. Mrs Joe, Estella and Miss Havisham would do a number on any young child’s head and perception of females. On the plus side we have Biddy. I’m not sure where to place Pip’s snoozing aged teacher.

I mention this because I recently read Dickens and Women by Michael Slater. Slater points out that the ratio of female characters to male characters is skewed highly towards male characters. As I’m re-reading through GE this time it is interesting (to me, anyway :-) ) how this fact may impact the male characters and my reading perceptions.

I mention this because I recently read Dickens and Women by Michael Slater. Slater points out that the ratio of female characters to male characters is skewed highly towards male characters. As I’m re-reading through GE this time it is interesting (to me, anyway :-) ) how this fact may impact the male characters and my reading perceptions.

Ch. 8. I had this sense of empathy with Pip finding himself sleeping in a corner of Pumblechook’s place, with the ceiling or corner literally at his nose. It is emblematic, to me, of the suffocating presence of Pumblechook.

Ch. 8. I had this sense of empathy with Pip finding himself sleeping in a corner of Pumblechook’s place, with the ceiling or corner literally at his nose. It is emblematic, to me, of the suffocating presence of Pumblechook. I agree with Peter’s thoughts about Estelle saying “she don’t.” But it does have, in a strange way, a sense of finality — like a door closing. “Don’t” is a consonance of harshness, perhaps. Reading that Pumblechook had his dignity ruffled was fun.

I had forgotten to say that Estella acts like both Havisham's daughter and her servant. Any of you who have read Tolstoy's Resurrection know what I mean. This pretty much puts her in no person's land. Go fetch the boy. Go take him away. Go feed him. She's my niece who Ive raised as my daughter. These dual and not entirely complementary roles might create a great deal of confusion and anger.

I had forgotten to say that Estella acts like both Havisham's daughter and her servant. Any of you who have read Tolstoy's Resurrection know what I mean. This pretty much puts her in no person's land. Go fetch the boy. Go take him away. Go feed him. She's my niece who Ive raised as my daughter. These dual and not entirely complementary roles might create a great deal of confusion and anger.

Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.

Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you want to know, I'll tell you. My first book, an ebook, seems to have left out an important passage or two. Then, unsatisfied with my response -- I was still reading it -- it started revealing only half words instead of whole ones. Then it inserted those missing passages in the wrong chapters. I think it's haunted and it wants me out.

So I obliged, and did what any ghost-fearing reader would do, I ditched it and moved into another edition. I have to say this one wins a prize. The only thing I can think of is someone translated G.E. into a foreign language, and then someone else took the translated copy and translated back into English. There are entire sentences in this version -- and I do mean version -- that only remotely resemble the originals. It's hilarious. A book written in English being read by and English reader, and it's like reading a translation. I'm saving this one.

So I downloaded a third version, and this seems to be a faithful copy, although I still read with suspicion. I don't want to be lulled a second time into a false sense of security.

Xan wrote: "Who would have thought reading Dickens would be this much trouble.

Xan wrote: "Who would have thought reading Dickens would be this much trouble.I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well..."

Strangely enough, my Scribd account gave me access to the Barnes & Noble Classics edition, which had a nicely written and helpful introduction. But after about three weeks or so, the time limit for this edition was up. I never encountered that before with Scribd. I selected another edition — there were dozens to choose from.

Xan wrote: "Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.

I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you want to kno..."

Xan

Weird. I’ve never experienced or heard of such a thing.

I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you want to kno..."

Xan

Weird. I’ve never experienced or heard of such a thing.

Xan wrote: "Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.

I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you want to kno..."

Xan,

If you use an e-reader to enjoy Dickens, I can recommend the Delphi Classics edition. There is the odd spelling mistake now and then, very rarely though, but the text is exactly as it is in my printed versions of Dickens.

I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you want to kno..."

Xan,

If you use an e-reader to enjoy Dickens, I can recommend the Delphi Classics edition. There is the odd spelling mistake now and then, very rarely though, but the text is exactly as it is in my printed versions of Dickens.

Xan wrote: "Estella may be very pretty and very proud, and she may look down on Pip for being a commoner, but every so often she lets something like this out when telling Pumblechook he cannot meet Miss Havisham: “but you see she don’t."

Every now and then I come across "she don't" in conversations in Victorian novels, and this also happens in conversations between people who speak standard or even upper-class English. I don't know if there is some rule I don't know about working in the background in these cases. Unfortunately, I never noted down the examples - but maybe I will from now on in order to get to the roots of this problem.

Every now and then I come across "she don't" in conversations in Victorian novels, and this also happens in conversations between people who speak standard or even upper-class English. I don't know if there is some rule I don't know about working in the background in these cases. Unfortunately, I never noted down the examples - but maybe I will from now on in order to get to the roots of this problem.

Tristram wrote: "Xan wrote: "Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.

Tristram wrote: "Xan wrote: "Trials and Tribulations of reading Dickens.I'm on my third Great expectations book/version, and I've read only 9 chapters. What could possibly be the problem, you ask? Well, since you..."

Thanks, Tristram. I have it but it is not longer loading. It goes to La-La Land when I try. I need to take a closer look at what is gong on.

My Dickens collection is also very volatile. But whenever I restart my reader, it has always started working again, so far.

Xan wrote: "I had forgotten to say that Estella acts like both Havisham's daughter and her servant. Any of you who have read Tolstoy's Resurrection know what I mean. This pretty much puts her in no person's la..."

Xan wrote: "I had forgotten to say that Estella acts like both Havisham's daughter and her servant. Any of you who have read Tolstoy's Resurrection know what I mean. This pretty much puts her in no person's la..."I like this point a lot. Many of Dickens's female characters, as we've all discussed, are disappointingly stereotypical. Estella is kind of a harpy (as Tristram points out, designed to break hearts), but I get the sense there is a lot going on beneath the surface.

I don't know if there's much going on beneath Miss Havisham's surface, but she certainly is striking. Unforgettably so.

Tristram wrote: "Pip again is haunted by feelings of social inferiority and he cannot help thinking that Joe and his sister would be looked down upon by Estella and Miss Havisham"

Tristram wrote: "Pip again is haunted by feelings of social inferiority and he cannot help thinking that Joe and his sister would be looked down upon by Estella and Miss Havisham"I find Pip's humiliated devolution, if it makes sense to think of it that way, to be so well-rendered it's excruciating to read.

And in answer to Peter's question last time about whether "Mrs Joe was in some way reflective of how Dickens saw Catherine as an oppressor"--it doesn't strike me that way. I find Great Expectations to be much more realistic than the stories Dickens told about himself and his wife during his divorce. Everyone is so muddied in this book, and Pip most of all. I guess I don't see Mrs. Joe as a Catherine because she has no Dickensian counterpart to be the saint to her villain. Joe may have saintly qualities, but he's no patriarch.

I never thought of Mrs. Joe as in sone way representative of Dickens’ views about Catherine. I might have first thought it would be something more akin, possibly, to his own mother.

I never thought of Mrs. Joe as in sone way representative of Dickens’ views about Catherine. I might have first thought it would be something more akin, possibly, to his own mother. But that didn’t wholly work in my mind, either. I take the view that Mrs. Joe and Pip are the only two survivors of a family of nine. This is such tragedy, and they serve as a counterpoint to each other. I remember my grandmother telling me — you can have a group of siblings under one roof and no two are alike.

I feel Biddy is older than Pip, but how much older I don't know. Anyone have a guess?

I feel Biddy is older than Pip, but how much older I don't know. Anyone have a guess?That last passage of chapter 9 is interesting. It's as if Pip is explaining/apologizing for what is to come.

And then there is the man at the pub, file in hand. Very strange.

I don't know a lot about Dickens's wife Catherine but the little I know always gave me the impression that hers was more of a passive nature and that Dickens was, partly because of his mercurial nature, quite a domineering husband. That's why I can't really see a lot of Catherine in Mrs. Joe. Like John, I'd say that Mrs. Joe's determination and self-assertion may result from her biography, i.e. the fact that she is a survivor and that she had to learn to take care of herself (and her baby brother) from very early on. A bit like my grandmother, who also was a survivor and a refugee and had to track down her family after the war: She was one of the most hard-nosed, no-nonsense, two-fisted grannies I had ever clapped eyes on and she used to boss everyone around. She could drive hard bargains, make tasty breakfasts out of little and keep her house in shipshape at all times, and still I have extremely fond memories of her but that was probably because, fortunately, for whatever reason, I was her favourite grand-child and if she had a soft spot, I was its inhabitant.

As to Dickens's mother, I read somewhere that garrulous, all-over-the-place Mrs. Nickleby was her literary counterpart.

As to Dickens's mother, I read somewhere that garrulous, all-over-the-place Mrs. Nickleby was her literary counterpart.

The visit with Miss Havisham is as memorable as anything I have read by Dickens. It certainly has staying power.

The visit with Miss Havisham is as memorable as anything I have read by Dickens. It certainly has staying power.As somewhat an aside, William Faulkner has a short story entitled A Rose for Emily. It is a very haunting story. I cannot help but think that Faulkner may have been influenced by Miss Havisham for that story. Clearly, Faulkner may have been drawing upon a local oral tradition to create that story, but it seems to be influenced by Miss Havisham.

John wrote: "As somewhat an aside, William Faulkner has a short story entitled A Rose for Emily. It is a very haunting story. I cannot help but think that Faulkner may have been influenced by Miss Havisham for that story. Clearly, Faulkner may have been drawing upon a local oral tradition to create that story, but it seems to be influenced by Miss Havisham."

John wrote: "As somewhat an aside, William Faulkner has a short story entitled A Rose for Emily. It is a very haunting story. I cannot help but think that Faulkner may have been influenced by Miss Havisham for that story. Clearly, Faulkner may have been drawing upon a local oral tradition to create that story, but it seems to be influenced by Miss Havisham."Yes, that makes a lot of sense.

Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic.

Julie wrote: "Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic."

Julie wrote: "Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic."Maybe you have to go to horror? Something like Mr. Hyde? Dorian Gray? Both of those have alternate personalities or presentations, though.

Julie wrote: "John wrote: "Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic. "

Julie wrote: "John wrote: "Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic. "The uncle who was his niece's guardian in Woman in White comes the closest in my mind. Gave her away to a predator and didn't care a hoot. Never left his room. Only cared about his paintings collection. He was slimier thang Havisham, though.

Julie wrote: "John wrote: "As somewhat an aside, William Faulkner has a short story entitled A Rose for Emily. It is a very haunting story. I cannot help but think that Faulkner may have been influenced by Miss ..."

Julie wrote: "John wrote: "As somewhat an aside, William Faulkner has a short story entitled A Rose for Emily. It is a very haunting story. I cannot help but think that Faulkner may have been influenced by Miss ..."That is an interesting question. I could not come up with anyone as a fictional character, but I thought of a real life one: Howard Hughes.

His last years border on myth, but a Havisham myth I would stay. I have family in Las Vegas and there are stories about his last years on the top floor of the Desert Inn. Where nobody could see him and where the dusty rotting drapes were closed for years.

Xan wrote: "Julie wrote: "John wrote: "Can anybody think of a male equivalent to Miss Havisham? I'm drawing a blank. I can think of literary male recluses but they're not so dramatic. "

The uncle who was his ..."

Xan

Yes. Great suggestion. The uncle is a rather creepy individual who locks himself into a self-imposed world of his own creation. He, like Havisham, has little or no positive love or attachment for others who live in the same house.

Speculation is fun. The Woman in White was published in serial form from 1859-60 in Dickens’s ‘All the Year Round.’ Thus it predates by a slim margin of time Great Expectations. Dickens and Collins were close friends. Here is today’s speculation question … could Dickens’s depiction of the very strange Miss Havisham have been, in any way, suggested or imagined because of Dickens's reading of The Woman in White or conversations with Collins? Perhaps impossible ever to prove but it's summer and a good time to ponder ideas.

The uncle who was his ..."

Xan

Yes. Great suggestion. The uncle is a rather creepy individual who locks himself into a self-imposed world of his own creation. He, like Havisham, has little or no positive love or attachment for others who live in the same house.

Speculation is fun. The Woman in White was published in serial form from 1859-60 in Dickens’s ‘All the Year Round.’ Thus it predates by a slim margin of time Great Expectations. Dickens and Collins were close friends. Here is today’s speculation question … could Dickens’s depiction of the very strange Miss Havisham have been, in any way, suggested or imagined because of Dickens's reading of The Woman in White or conversations with Collins? Perhaps impossible ever to prove but it's summer and a good time to ponder ideas.

Dickens probably sought out personality types from all over. People he knew or knew of were favorites, but books were probably another source. And like you say he and Collins were great friends. I thought they borrowed from each other.

Dickens probably sought out personality types from all over. People he knew or knew of were favorites, but books were probably another source. And like you say he and Collins were great friends. I thought they borrowed from each other.

In my Penguin edition it say that there was a now-forgotten novelist by the name of James Payn, who says that he gave Dickens the idea for Miss Havisham by telling him about an acquaintance of his. Apparently, Payn was not miffed that Dickens made use of this idea.

A male literary character that reminds me of Miss Havisham to a certain degree is Bartleby the Scrivener.

A male literary character that reminds me of Miss Havisham to a certain degree is Bartleby the Scrivener.

Wasn't Havisham a creation over time? Wasn't Miss Wade and her misandry a Havisham in the making? Wasn't she trying to do to Tattycoram what Havisham is doing to Estella? And older widows living alone in big houses wearing old dresses was more a thing back then than now. Havisham is a variation on Miss Wade and a certain type of older widow of the times.

Wasn't Havisham a creation over time? Wasn't Miss Wade and her misandry a Havisham in the making? Wasn't she trying to do to Tattycoram what Havisham is doing to Estella? And older widows living alone in big houses wearing old dresses was more a thing back then than now. Havisham is a variation on Miss Wade and a certain type of older widow of the times.I had a great aunt who was a spry young thing in the late 1800s. She traveled a lot and had more than a few beaus. By the time I met her, she was shriveled up and living in an ancient house (replete with barn) with clocks everywhere ticking like mad, and she wore dresses that I swore women wore during the American revolution.

"'Who is it?' said the lady at the table. 'Pip, Ma'am.'"

Chapter 8

John McLenan

1860

Dickens's Great Expectations,

Harper's Weekly

Text Illustrated:

“Who is it?” said the lady at the table.

“Pip, ma’am.”

“Pip?”

“Mr. Pumblechook’s boy, ma’am. Come—to play.”

“Come nearer; let me look at you. Come close.”

It was when I stood before her, avoiding her eyes, that I took note of the surrounding objects in detail, and saw that her watch had stopped at twenty minutes to nine, and that a clock in the room had stopped at twenty minutes to nine.

“Look at me,” said Miss Havisham. “You are not afraid of a woman who has never seen the sun since you were born?”

I regret to state that I was not afraid of telling the enormous lie comprehended in the answer “No.”

“Do you know what I touch here?” she said, laying her hands, one upon the other, on her left side.

“Yes, ma’am.” (It made me think of the young man.)

“What do I touch?”

“Your heart.”

“Broken!”

She uttered the word with an eager look, and with strong emphasis, and with a weird smile that had a kind of boast in it. Afterwards she kept her hands there for a little while, and slowly took them away as if they were heavy.

Commentary:

McLenan features Miss Havisham prominently in five plates whereas, for example, Magwitch occurs in five, Joe in seven, and Pip in 29. However, in the McLenan series she tends to dominate the first dozen larger-scale illustrations, including "'Who is it?' said the lady at the table. 'Pip, Ma'am.'" Contrast this image of the reclusive senior with the glowing image from Pip's memory in the Stone series, Pip Waits on Miss Havisham. McLenan in contrast presents a despondent, introverted, somewhat elderly and angular bride in front of her mirror. McLenan has responded more accurately (if less delightfully) to the letter-press than Marcus Stone.

McLenan sets his crone in the midst of her furnishings and belongings. As in the text, open trunks (left and right) covered with clothing frame the scene, and an inward-gazing Miss Havisham in an attitude of despondency, hand supporting her head, sits before an oval mirror which has four candlelabra attached. Faithful to his copy, the illustrator has included such details as the white shoe on the dressing table (Pip indicates that he can see the other white shoe on her foot, which McLenan conceals beneath her skirts). In Stone's plate describing Pip's meeting Miss Havisham, he carries a cloth cap such as was worn by the British working class, whereas in McLenan's plate it is a brimmed felt hat, which the American artist has supplied from his own experience and period.

"Pip Waits on Miss Havisham"

Chapter 8

Marcus Stone

1862

Text Illustrated:

"In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials — satins, and lace, and silks — all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on--the other was on the table near her hand--her veil was but half-arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a prayer-book, all confusedly heaped about the looking glass. . . . I saw that the bride within the bridal dress had withered like the dress, and the flowers, and had no brightness left but the brightness of her sunken eyes. I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose had shrunk to skin and bone."

Commentary:

In "Pip Waits on Miss Havisham," in contradiction to the letter-press, Stone depicts her as youthful and attractive. Commanding in presence, she is lit by candelabra, enthroned as it were before her humble supplicant, the blacksmith's boy. Cap in hand, Pip slightly bends at the knees, while the large-eyed, imperious woman with the elaborately arranged blonde hair and bare-shouldered, voluminous wedding dress (apparently no worse for a number of years of wear), her mirror just disappearing off the right-hand margin. Contrast this glowing image from Pip's memory with the despondent, introverted, somewhat elderly and angular bride in front of her mirror given us by McLenan, who has responded more accurately (if less delightfully) to the letter-press.

As we turn in the 1861 Philadelphia volume we encounter the vignetted illustration "'Who is it?' said the lady at the table. 'Pip, ma'am.'--" before we actually find the same moment in the letter-press. Whereas Stone had filled the frame with the enchanting fairy godmother, McLenan sets his crone in the midst of her furnishings and belongings. As in the text, open trunks (left and right) covered with clothing frame the scene, and an inward-gazing Miss Havisham in an attitude of despondency, hand supporting her head, sits before an oval mirror which has four candlelabra attached. Faithful to his copy, the illustrator has included such details as the white shoe on the dressing table (Pip indicates that he can see the other white shoe on her foot, which McLenan conceals beneath her skirts). Although neither artist has depicted the faded flowers, the watch and chain are evident just to the right of Miss Havisham's left elbow in Stone's version, important symbols of her rejection of the passage of time. An interesting if minor detail which varies in the two plates is Pip's hat: in Stone's plate, it is a cloth cap such as was worn by the British working class, whereas in McLenan's plate it is a brimmed felt hat, which the American artist supplied from his own experience and period.

Whereas the American artist has depicted the jewels that the text twice mentions, these are not present in Stone's plate, which nevertheless glimmers by the light of four powerful candles in contrast to the faint glare of the four tapers in McLenan's. Without unnecessarily dwelling upon such minutiae, one may simply note that the overall effect of the American periodical illustration is awkward and stilted, although technically accurate, whereas that of the English illustration is dramatic and powerful because Stone has reduced the scene to its essentials, and placed the contrasting figures in close proximity, balancing the difference in their heights by placing three candles above Pip and creating a sense of the numinous that the American plate entirely lacks.

Miss Havisham remains a static, almost blind figure in McLenan's 'It's a great cake. "'A bride-cake. Mine!" and "'Which I meantersay, Pip.'," both of which are nevertheless accurate in the details of each scene, the dining room and the boudoir, although Pip is perhaps too well dressed for a mere labouring boy and one wonders how the latter scene is lit, considering that the windows are covered but the candles above Estella are unlit. Interestingly, all three Havisham plate make mirrors central features, though none of them actually reflects anything. These "blind" mirrors may reflect the psychological blindness of Miss Havisham to her true condition; in David Lean's 1946 film, Miss Havisham is, as Regina Barreca notes, "framed next to mirrors in a number of scenes, making visual the way the spinster wishes to multiply her image through Estella". However, McLenan's mirrors return no image, suggesting the sterility of lifelessness of Satis House which accords well with the static, rigid depiction of the figures.

"She gave a contemptuous toss . . . . and left me"

Chapter 8

F. A. Fraser

Text Illustrated:

"She came back, with some bread and meat and a little mug of beer. She put the mug down on the stones of the yard, and gave me the bread and meat without looking at me, as insolently as if I were a dog in disgrace. I was so humiliated, hurt, spurned, offended, angry, sorry,—I cannot hit upon the right name for the smart—God knows what its name was,—that tears started to my eyes. The moment they sprang there, the girl looked at me with a quick delight in having been the cause of them. This gave me power to keep them back and to look at her: so, she gave a contemptuous toss—but with a sense, I thought, of having made too sure that I was so wounded—and left me.

But when she was gone, I looked about me for a place to hide my face in, and got behind one of the gates in the brewery-lane, and leaned my sleeve against the wall there, and leaned my forehead on it and cried. As I cried, I kicked the wall, and took a hard twist at my hair; so bitter were my feelings, and so sharp was the smart without a name, that needed counteraction.

My sister’s bringing up had made me sensitive. In the little world in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt as injustice. It may be only small injustice that the child can be exposed to; but the child is small, and its world is small, and its rocking-horse stands as many hands high, according to scale, as a big-boned Irish hunter. Within myself, I had sustained, from my babyhood, a perpetual conflict with injustice. I had known, from the time when I could speak, that my sister, in her capricious and violent coercion, was unjust to me. I had cherished a profound conviction that her bringing me up by hand gave her no right to bring me up by jerks. Through all my punishments, disgraces, fasts, and vigils, and other penitential performances, I had nursed this assurance; and to my communing so much with it, in a solitary and unprotected way, I in great part refer the fact that I was morally timid and very sensitive.

I got rid of my injured feelings for the time by kicking them into the brewery wall, and twisting them out of my hair, and then I smoothed my face with my sleeve, and came from behind the gate. The bread and meat were acceptable, and the beer was warming and tingling, and I was soon in spirits to look about me."

Commentary:

With the example of Marcus Stone's 1862 Illustrated Library Edition frontispiece before him, Fraser could well; have decided to romanticize Pip's initial visit to Satis House. But instead of air air of mystery or an emotional effusion based on Pip's first encounter with the beautiful but aloof Estella and the mysterious recluse who has adopted her, Fraser gives us a plain, sour-faced adolescent. And in place of the candle-lit halls of the brewer-heiress's mansion, Fraser chooses as his backdrop the mundane, utterly unexotic brewery yard. Marcus Stone depicted Miss Havisham as a ravishing beauty enveloped in an air of mystery, part of which lies in the origins of Estella.

Although the young artist collaborated closely with the author on the eight engravings in the 1862 first volume edition, Stone’s style had veered away from the literal realism of the sixties' novel and towards the creation of an appropriate mood or atmosphere in both the opening scene in the churchyard and in the scenes at Satis House. Stone's atmospheric treatment is most evident in Pip Waits on Miss Havisham, a full-page plate which realises not merely Stone's initial reading of the serialised in All the Year Round, but also the young illustrator's conversations with the author himself. This initial visit to Satis House leads Pip into the greater world beyond the marshes. And yet in the Fraser illustration one has almost no sense of the momentous nature of the visit in Fraser's illustration.

Fraser's depiction of Estella against the backdrop of the barrels in the abandoned brew-house is certainly the most prosaic treatment of Dickens's difficult heroine offered by the various nineteenth and early twentieth-century illustrators of the novel. She is statuesque and attractive as an adult in the other programs of illustration, but Fraser depicts her here in his first regular illustration of her begins as a sour-faced, bushy-haired adolescent in the Fraser sequence. The illustrator has chosen to introduce Estella ahead of the other female characters (Miss Havisham, Mrs. Joe, Biddy, Molly, Mrs. Pocket, and Clara) in the frontispiece. Her reappearance in this fifth illustration underscores her importance in the plot. Fraser has made her a society beauty in his first illustration, but here he focussed upon her negative qualities: her truculence, self-assertiveness, negativity, and class consciousness as she stonily remarks, "You are to wait here, you boy", and then regards him "insolently" and dismisses him with "a contemptuous toss" of her head of the visitor whom she had initially dismissed as "a common labouring boy". The illustration, therefore, underscores the negative aspects of the couple's initial meeting which leaves Pip feeling "humiliated, hurt. spurned, offended, angry, [and] sorry" .

"In an armchair, with an elbow resting on the table"

Chapter 8

Charles Green

1877

Gadshill Edition

Text Illustrated:

Whether I should have made out this object so soon if there had been no fine lady sitting at it, I cannot say. In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials,—satins, and lace, and silks,—all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on,—the other was on the table near her hand,—her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a Prayer-Book all confusedly heaped about the looking-glass.

It was not in the first few moments that I saw all these things, though I saw more of them in the first moments than might be supposed. But I saw that everything within my view which ought to be white, had been white long ago, and had lost its lustre and was faded and yellow. I saw that the bride within the bridal dress had withered like the dress, and like the flowers, and had no brightness left but the brightness of her sunken eyes. I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose had shrunk to skin and bone. Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly waxwork at the Fair, representing I know not what impossible personage lying in state. Once, I had been taken to one of our old marsh churches to see a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress that had been dug out of a vault under the church pavement. Now, waxwork and skeleton seemed to have dark eyes that moved and looked at me. I should have cried out, if I could.

Commentary:

In contrast to Green's realistic and detailed study of the demented heiress in her disordered boudoir, Marcus Stone’s style in Pip Waits on Miss Havisham (see below) from the first volume edition veers deliberately away from literal realism towards the creation of an appropriate mood or atmosphere, that of a fairy-tale encounter between the poor child and the fairy godmother. The 1862 plate Pip Waits on Miss Havisham may well reflect young Stone's initial reading of the serial instalment in All the Year Round, but also the young illustrator's conversations with the author himself. Working three decades after Dickens's death, Green enjoyed no such advantage, but did have the work of previous illustrators upon which to draw.

I find this next one rather creepy:

"Miss Havisham"

Chapter 8

Harry Furniss

1910

Dickens's Great Expectations, Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

Whether I should have made out this object so soon if there had been no fine lady sitting at it, I cannot say. In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials,—satins, and lace, and silks,—all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on, — the other was on the table near her hand, — her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a Prayer-Book all confusedly heaped about the looking-glass. [Chapter VIII]

Commentary:

Furniss conveys Miss Havisham's mania through the jagged lines and cascading folds in her dress, as if she is a distorted reflection in a broken mirror. Her skeletal neck and protruding eyes contribute to the sense that she is emaciated, that she has skrivelled up inside her bridal gown. Her regal posture and seated pose contribute to the impression that she is enthroned, with erect pose and a bridal headpiece suggestive of a crown. In Pip's little Kentish village, she is the acme of the social pyramid.

"Miss Havisham"

Chapter 8

Harry Furniss

1910

Dickens's Great Expectations, Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

Whether I should have made out this object so soon if there had been no fine lady sitting at it, I cannot say. In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials,—satins, and lace, and silks,—all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on, — the other was on the table near her hand, — her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a Prayer-Book all confusedly heaped about the looking-glass. [Chapter VIII]

Commentary:

Furniss conveys Miss Havisham's mania through the jagged lines and cascading folds in her dress, as if she is a distorted reflection in a broken mirror. Her skeletal neck and protruding eyes contribute to the sense that she is emaciated, that she has skrivelled up inside her bridal gown. Her regal posture and seated pose contribute to the impression that she is enthroned, with erect pose and a bridal headpiece suggestive of a crown. In Pip's little Kentish village, she is the acme of the social pyramid.

"Well? You can break his heart"

Chapter 8

H. M. Brock

1901-1903

Text Illustrated:

“Call Estella,” she repeated, flashing a look at me. “You can do that. Call Estella. At the door.”

To stand in the dark in a mysterious passage of an unknown house, bawling Estella to a scornful young lady neither visible nor responsive, and feeling it a dreadful liberty so to roar out her name, was almost as bad as playing to order. But she answered at last, and her light came along the dark passage like a star.

Miss Havisham beckoned her to come close, and took up a jewel from the table, and tried its effect upon her fair young bosom and against her pretty brown hair. “Your own, one day, my dear, and you will use it well. Let me see you play cards with this boy.”

“With this boy? Why, he is a common laboring boy!”

I thought I overheard Miss Havisham answer,—only it seemed so unlikely,—“Well? You can break his heart.”

“What do you play, boy?” asked Estella of myself, with the greatest disdain.

“Nothing but beggar my neighbor, miss.”

“Beggar him,” said Miss Havisham to Estella. So we sat down to cards."

"Leave this lad to me, Ma'am; leave this lad to me"

chapter 9

John McLenan

1860

Harper's Weekly 4 (22 December 1860)

T. B. Peterson single-volume edition of 1861 used as the frontispiece in the volume.

Text Illustrated:

“Well, boy,” Uncle Pumblechook began, as soon as he was seated in the chair of honor by the fire. “How did you get on up town?”

I answered, “Pretty well, sir,” and my sister shook her fist at me.

“Pretty well?” Mr. Pumblechook repeated. “Pretty well is no answer. Tell us what you mean by pretty well, boy?”

Whitewash on the forehead hardens the brain into a state of obstinacy perhaps. Anyhow, with whitewash from the wall on my forehead, my obstinacy was adamantine. I reflected for some time, and then answered as if I had discovered a new idea, “I mean pretty well.”

My sister with an exclamation of impatience was going to fly at me,—I had no shadow of defence, for Joe was busy in the forge,—when Mr. Pumblechook interposed with “No! Don’t lose your temper. Leave this lad to me, ma’am; leave this lad to me.” Mr. Pumblechook then turned me towards him, as if he were going to cut my hair, and said,—

“First (to get our thoughts in order): Forty-three pence?”

I calculated the consequences of replying “Four Hundred Pound,” and finding them against me, went as near the answer as I could—which was somewhere about eightpence off. Mr. Pumblechook then put me through my pence-table from “twelve pence make one shilling,” up to “forty pence make three and fourpence,” and then triumphantly demanded, as if he had done for me, “Now! How much is forty-three pence?” To which I replied, after a long interval of reflection, “I don’t know.” And I was so aggravated that I almost doubt if I did know.

Mr. Pumblechook worked his head like a screw to screw it out of me, and said, “Is forty-three pence seven and sixpence three fardens, for instance?”

“Yes!” said I. And although my sister instantly boxed my ears, it was highly gratifying to me to see that the answer spoilt his joke, and brought him to a dead stop.

“Boy! What like is Miss Havisham?” Mr. Pumblechook began again when he had recovered; folding his arms tight on his chest and applying the screw."

Commentary:

Since Pip considers that everything that he has seen of Miss Havisham inside Satis House is simply too bizarre to be credited by his stern sister and her pompous uncle, Pip gives them a far-fetched account that he nevertheless feels will be more believable. McLenan here captures the very essence of Pumblechook here: fat, complacent, and egotistical, the village's principal merchant takes his paternalistic relationship with Mrs. Joe veery seriously. He also enjoys imposing his values (as represented by the arithmetical sums he is wont to throw at Pip) upon the unlettered, unschooled boy. Mrs. Joe's threatening gesture reveals her customary way of dealing with her brother, but Pumblechook puts back her menacing fist, proposing to get to the bottom of Pip's experiences at Satis House. At a glance the reader correctly surmises that Pip in retrospect regards the menacing pair as oppressors and interrogators.

And then they both stared at me

Chapter 9

H. M. Brock

Test Illustrated:

“Why, don’t you know,” said Mr. Pumblechook, testily, “that when I have been there, I have been took up to the outside of her door, and the door has stood ajar, and she has spoke to me that way. Don’t say you don’t know that, Mum. Howsever, the boy went there to play. What did you play at, boy?”

“We played with flags,” I said. (I beg to observe that I think of myself with amazement, when I recall the lies I told on this occasion.)

“Flags!” echoed my sister.

“Yes,” said I. “Estella waved a blue flag, and I waved a red one, and Miss Havisham waved one sprinkled all over with little gold stars, out at the coach-window. And then we all waved our swords and hurrahed.”

“Swords!” repeated my sister. “Where did you get swords from?”

“Out of a cupboard,” said I. “And I saw pistols in it,—and jam,—and pills. And there was no daylight in the room, but it was all lighted up with candles.”

“That’s true, Mum,” said Mr. Pumblechook, with a grave nod. “That’s the state of the case, for that much I’ve seen myself.” And then they both stared at me, and I, with an obtrusive show of artlessness on my countenance, stared at them, and plaited the right leg of my trousers with my right hand."

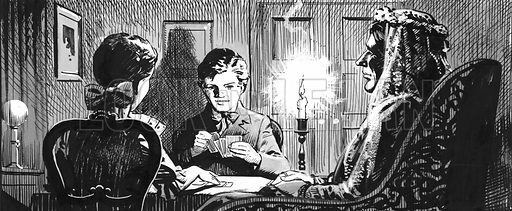

A Stranger at the Jolly Bargemen

Chapter 10

F. W. Pailthorpe

c. 1900

Garnett Edition

Text Illustrated:

"There was a bar at the Jolly Bargemen, with some alarmingly long chalk scores in it on the wall at the side of the door, which seemed to me to be never paid off. They had been there ever since I could remember, and had grown more than I had. But there was a quantity of chalk about our country, and perhaps the people neglected no opportunity of turning it to account.

It being Saturday night, I found the landlord looking rather grimly at these records; but as my business was with Joe and not with him, I merely wished him good evening, and passed into the common room at the end of the passage, where there was a bright large kitchen fire, and where Joe was smoking his pipe in company with Mr. Wopsle and a stranger. Joe greeted me as usual with “Halloa, Pip, old chap!” and the moment he said that, the stranger turned his head and looked at me.

He was a secret-looking man whom I had never seen before. His head was all on one side, and one of his eyes was half shut up, as if he were taking aim at something with an invisible gun. He had a pipe in his mouth, and he took it out, and, after slowly blowing all his smoke away and looking hard at me all the time, nodded. So, I nodded, and then he nodded again, and made room on the settle beside him that I might sit down there.

But as I was used to sit beside Joe whenever I entered that place of resort, I said “No, thank you, sir,” and fell into the space Joe made for me on the opposite settle. The strange man, after glancing at Joe, and seeing that his attention was otherwise engaged, nodded to me again when I had taken my seat, and then rubbed his leg—in a very odd way, as it struck me.

“You was saying,” said the strange man, turning to Joe, “that you was a blacksmith.”

"At The Three Jolly Bargemen"

Chapter 10

Harry Furniss

1910

Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

"And here I may remark that when Mr. Wopsle referred to me, he considered it a necessary part of such reference to rumple my hair and poke it into my eyes. I cannot conceive why everybody of his standing who visited at our house should always have put me through the same inflammatory process under similar circumstances. Yet I do not call to mind that I was ever in my earlier youth the subject of remark in our social family circle, but some large-handed person took some such ophthalmic steps to patronize me.

All this while, the strange man looked at nobody but me, and looked at me as if he were determined to have a shot at me at last, and bring me down. But he said nothing after offering his Blue Blazes observation, until the glasses of rum and water were brought; and then he made his shot, and a most extraordinary shot it was.

It was not a verbal remark, but a proceeding in dumb-show, and was pointedly addressed to me. He stirred his rum and water pointedly at me, and he tasted his rum and water pointedly at me. And he stirred it and he tasted it; not with a spoon that was brought to him, but with a file.

He did this so that nobody but I saw the file; and when he had done it he wiped the file and put it in a breast-pocket. I knew it to be Joe’s file, and I knew that he knew my convict, the moment I saw the instrument. I sat gazing at him, spell-bound. But he now reclined on his settle, taking very little notice of me, and talking principally about turnips.

There was a delicious sense of cleaning-up and making a quiet pause before going on in life afresh, in our village on Saturday nights, which stimulated Joe to dare to stay out half an hour longer on Saturdays than at other times. The half-hour and the rum and water running out together, Joe got up to go, and took me by the hand.

“Stop half a moment, Mr. Gargery,” said the strange man. “I think I’ve got a bright new shilling somewhere in my pocket, and if I have, the boy shall have it.”

He looked it out from a handful of small change, folded it in some crumpled paper, and gave it to me. “Yours!” said he. “Mind! Your own.”

I thanked him, staring at him far beyond the bounds of good manners, and holding tight to Joe. He gave Joe good-night, and he gave Mr. Wopsle good-night (who went out with us), and he gave me only a look with his aiming eye,—no, not a look, for he shut it up, but wonders may be done with an eye by hiding it."

The beginning of Chapter 8, with the description of Pumblechook’s place, has a certain amount of hilarity to it.

The beginning of Chapter 8, with the description of Pumblechook’s place, has a certain amount of hilarity to it.“Peppercorny and farineous.” I had to look up farineous, but the point about the premises was great.

Thanks for giving us the wonderful illustrations, Kim: I have always found that Harry Furniss's figures look quite elfin, sometimes too much so, but in the case of Miss Havisham, he really bull's-eyed her character, as far as I am concerned. The haggard expression and the cadaverous, spider-webby aura about her are inimitable. I was also impressed with Marcus Stone's rendition of Miss Havisham, although he presented her as quite young - but she looks like a marble idol, and that is what she made herself to herself: an idol of pain, disappointent and being wronged. She takes a lot of pride in being a victim.

One memory that stayed with me for years and came back to me in Chapter 8 was the card game.

One memory that stayed with me for years and came back to me in Chapter 8 was the card game.Estella remarked that Pip refers to the Knaves as Jacks, and has coarse hands and thick boots. That memory had stayed with me. The level of details that Dickens uses is stunning because they not only are descriptive but add to the personalities.

That was also one of the details I remembered - partly because as someone who speaks English as his second language only, I found it interesting that I was actually taught to call those cards Jacks. "Knaves" I never heard about before in that context; that word has quite a sinister association to my mind.

I was taught Jacks too. Perhaps this is why I'm a lousy card player?

I was taught Jacks too. Perhaps this is why I'm a lousy card player?One-Eyed Jacks and the King with the axe.

Xan wrote: "Tarot cards are more interesting."

Quite hauntingly so. I just watched the movie Nightmare Alley, both versions, where they play a role.

Quite hauntingly so. I just watched the movie Nightmare Alley, both versions, where they play a role.

Pat Nicolle

Chapter 8

Text Illustrated:

Miss Havisham beckoned her to come close, and took up a jewel from the table, and tried its effect upon her fair young bosom and against her pretty brown hair. “Your own, one day, my dear, and you will use it well. Let me see you play cards with this boy.”

“With this boy? Why, he is a common labouring-boy!”

I thought I overheard Miss Havisham answer,—only it seemed so unlikely,—“Well? You can break his heart.”

“What do you play, boy?” asked Estella of myself, with the greatest disdain.

“Nothing but beggar my neighbour, miss.”

“Beggar him,” said Miss Havisham to Estella. So we sat down to cards.

It was then I began to understand that everything in the room had stopped, like the watch and the clock, a long time ago. I noticed that Miss Havisham put down the jewel exactly on the spot from which she had taken it up. As Estella dealt the cards, I glanced at the dressing-table again, and saw that the shoe upon it, once white, now yellow, had never been worn. I glanced down at the foot from which the shoe was absent, and saw that the silk stocking on it, once white, now yellow, had been trodden ragged. Without this arrest of everything, this standing still of all the pale decayed objects, not even the withered bridal dress on the collapsed form could have looked so like grave-clothes, or the long veil so like a shroud.

So she sat, corpse-like, as we played at cards; the frillings and trimmings on her bridal dress, looking like earthy paper. I knew nothing then of the discoveries that are occasionally made of bodies buried in ancient times, which fall to powder in the moment of being distinctly seen; but, I have often thought since, that she must have looked as if the admission of the natural light of day would have struck her to dust.

“He calls the knaves Jacks, this boy!” said Estella with disdain, before our first game was out. “And what coarse hands he has! And what thick boots!”

I had never thought of being ashamed of my hands before; but I began to consider them a very indifferent pair. Her contempt for me was so strong, that it became infectious, and I caught it.

She won the game, and I dealt. I misdealt, as was only natural, when I knew she was lying in wait for me to do wrong; and she denounced me for a stupid, clumsy labouring-boy.

Today I have the pleasure to introduce a key chapter of the novel – namely the first encounter of Pip and Miss Havisham, but, what is even more important, the first encounter of Pip and Estella.

After a dismal breakfast at Mr. Pumblechook’s, where Pip is treated to the most meagre morsels of the repast, such as crumbs and watered-down milk, as well as to arithmetics, his host and he go to see Miss Havisham. The first impression we get of the manor, which is, ironically called Satis House, though it lacks so much, already gives away a lot about Miss Havisham:

How did this description strike you?

They are received by a young girl, who is extremely beautiful but also quite haughty and who gives Mr. Pumblechook a downer by pointing out to him that Miss Havisham has no wish to see him but only the boy, and so Mr. Pumblechook has to stay outside. We get another telling impression of the premises here:

Pip somehow feels intimidated by Estella, who calls him “boy” all the time although she is not really much older than he. She leaves him in front of a door in a dark passageway, and there is nothing for him but to knock at the door, and soon he finds himself in the presence of Miss Havisham, who is described as follows:

Again, what were your first impressions when reading this description?

Of course, Pip is very diffident in the presence of this strange lady and only answers her questions in monosyllables, all the while taking in other details, e.g. the fact that every clock or watch in the room has stopped at twenty minutes to nine, that the lady apparently had never put on her second shoe, and that when she refers to her broken heart, she shows “a weird smile that had a kind of boast in it”. It’s quite interesting a small boy like Pip should notice this last detail.

Miss Havisham makes Estella come back and play at cards with Pip. At first, Estella does not want to but the old lady tells the young girl something that Pip at first thought he did not hear correctly, namely that she could break his heart. Estella wins all games, she “beggars” [!] Pip and she also makes him feel low and common by making fun of his hands, his boots and the fact that he calls the knaves Jacks. Pip, of course, feels very ill at ease

and finally begs to be given permission to leave, which Miss Havisham grants, not before telling him to come back in six days and asking him what he thinks of Estella. Pip then is led outside by Estella and given something to eat and drink. He is blinded by the daylight outside and has the impression that he has been inside the House not just a few hours but days, and while he is eating and drinking in the yard, he has strange visions of Estella appearing in different places but also of Miss Havisham hanging by the neck and calling out for him. Estella’s bad treatment of him makes him doubt his own value and wish he had not been brought up so common. He also reflects on all the injustices he suffered from his sister and the following quotation shows the more mature narrator:

A very moving passage, which tells us, maybe, also something of the injustices Dickens had suffered when he was a child and had to work in a factory instead of receiving proper education.

The end of the chapter shows that Estella has also achieved some influence over Pip because on his four-mile way back home, Pip muses on all the things Estella pointed out to him and Miss Havisham as showing him to be a low-bred person.

What might Miss Havisham’s motives be for having Pip come over to her house? What do you think of Estella? Is she a victim of Miss Havisham, or in league with her?

Miss Havisham, by the way, reminded me quite a lot of Mrs. Clennam from Little Dorrit in that both characters seem to take a grim kind of pleasure in confining themselves to their rooms and making themselves prisoners of their own past and feelings of superiority. Do you notice any differences between these two ladies? – Like Little Dorrit, also Great Expectations seems to work with the motif of different kinds of imprisonment. What forms of prison come to your notice when reading Great Expectations?