Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Three Detective Anecdotes

Short Reads, led by our members

>

Detective Stories by Dickens - 2nd and 3rd Summer Reads 2022 (hosted by Sara and Lori)

What a fun story indeed! I enjoy that Wield is telling the story about Witchem's "artful touch" to brag on him and his sly technique. Witcher had a keen eye to be able to notice the exact thief and then to be able to perform his move with such dexterity!

What a fun story indeed! I enjoy that Wield is telling the story about Witchem's "artful touch" to brag on him and his sly technique. Witcher had a keen eye to be able to notice the exact thief and then to be able to perform his move with such dexterity! When the two officers meet up with Mr. Tatt, he asks Wield What are you doing here? On the look out for some of your old friends?

Field was pretty well known by the thieves on his beat, so he probably knew exactly who he was looking for.

And when are criminals ever going to understand, that when you try to run, it's worse for you! I wonder if his running from the court proceedings, a brazen move on his part, gave him a heavier penalty - transportation. But maybe, not, after reading in Jean's informative post about it being common to be transported for stealing fruit.

I enjoyed this story very much! Witchem definitely knew his stuff and how the swell mob operated. He also had a good eye and kept a watch on his surroundings, even while having a friendly drink. The thief in this story was bold as brass! You'd need to get pretty close to a person, facing them I guess, to steal a tie pin. Then running out of court, swimming across a river, and climbing a tree to try to escape - bold moves. Reminds me a bit of the Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist.

Sara I love that you mentioned David Niven in The Pink Panther - that's a fun point of reference for swell mobs!

Sort of related - emigration to Australia was the end goal for the women who lived at Urania Cottage, the home Dickens helped establish and manage for "fallen" women. The plan was to rehabilitate them, give them responsibilities within the home, teach them skills, then send them to Australia to marry and start a fresh life.

Sara I love that you mentioned David Niven in The Pink Panther - that's a fun point of reference for swell mobs!

Sort of related - emigration to Australia was the end goal for the women who lived at Urania Cottage, the home Dickens helped establish and manage for "fallen" women. The plan was to rehabilitate them, give them responsibilities within the home, teach them skills, then send them to Australia to marry and start a fresh life.

Jean Thank you for the detailed info on transportation. I always think of Jean val Jean being sent to prison for stealing bread as a reminder of how stiff punishments were in those days. I imagine it would have felt quite different to elect to emigrate than to be sentenced to it. For one thing, you would be free in the one instance and forced to labor in the other.

Jean Thank you for the detailed info on transportation. I always think of Jean val Jean being sent to prison for stealing bread as a reminder of how stiff punishments were in those days. I imagine it would have felt quite different to elect to emigrate than to be sentenced to it. For one thing, you would be free in the one instance and forced to labor in the other.Lori You are right that the familiarity of the detectives with the criminals would have made them easier to spot. Perhaps your one hope was to escape, since harsh punishment was the rule.

Cozy Can't help thinking it took a lot of skill to be a good pick pocket and nerve! I also thought of the Artful Dodger, and the title of the story sort of brings him to mind as well.

Thanks for the reminder that the purpose of the house for fallen women was to prepare them to be sent to Australia. I imagine there were a surplus of men waiting to marry them.

Janelle has described from the Australian point of view, with Australian documentation, exactly what happened to those arriving as convicts from Britain.

I've also written detailed posts about Urania Cottage ...

(Both these can be found if you are interested, by using the search facility. I haven't written more here, because they are perhaps not very germane to the story.)

I've also written detailed posts about Urania Cottage ...

(Both these can be found if you are interested, by using the search facility. I haven't written more here, because they are perhaps not very germane to the story.)

Again, it was so fun to have Detective Wield spin another tale.

Again, it was so fun to have Detective Wield spin another tale. I loved how the police outwitted the criminals in the end. Thanks for picking these stories, Sara - I've very much enjoyed reading them.

Thank you, Sara! Excellent notes.

Thank you, Sara! Excellent notes.I liked it that here the hero of the story is not Wield (as I expected after the first story), but his colleague. In what has become the standard of crime fiction now, I find it a bit tiresome that the main detective is (practically) always right and his well-meaning helper often wrong.

Do you think the thieves knew that the detectives were the police? It was rather imprudent of them to attack the detectives' friend in this case, wasn't it? Or do you think they could not know it, even though these detectives were often working the Epsom?

As for transportation, I think it's also terribly disrespectful to people who live in the destination country. But I guess that's beyond the scope of the current discussion.

I gather the thief was an experienced one - well, he knew what the touch meant, for one (so I don't think he was charged just for the pin, although we are not told about it).

Lori wrote: "There is another essay called The Detective Police written by Dickens in 1850 which I haven’t read completely but understand it is an account of a group of detectives and sergeants ..."

Lori wrote: "There is another essay called The Detective Police written by Dickens in 1850 which I haven’t read completely but understand it is an account of a group of detectives and sergeants ..."I just read this story and for some reason, I kept picturing a group of cowboys sitting around a campfire at night, telling their stories. I don't read (or even especially care for) westerns, but that was the image that kept popping into my head as I read it.

Kathleen wrote: "This little anecdote sent me to google multiple times! I didn't know what a "Swell Mob" was or "Quarter Sessions," and I looked up a few more things just for details, like calling the pin a "prop."..."

Kathleen wrote: "This little anecdote sent me to google multiple times! I didn't know what a "Swell Mob" was or "Quarter Sessions," and I looked up a few more things just for details, like calling the pin a "prop."..."The one that threw me in "The Pair of Gloves" was when they went to the pub and drank half-and-half. I don't know about you, but to me, that's a dairy product, so I kind of figured there was another version. Looking it up, I see its a mix of ale and bitters, and that makes a lot more sense!

The Sofa

The SofaSummary:

Sergeant Dornton is approached by officials of Saint Blank Hospital regarding a rash of thefts being perpetrated upon students at the hospital. They are unable to leave any item in their great-coats without having the item stolen. Concerned with the damage that might be done to the reputation of the institution by these pervasive thefts, the gentlemen in charge decide to approach the police for assistance.

Dornton questions the officials and finds that all the missing items are taken from one particular room, a rather bare one in which there are a few tables and pegs for leaving hats and coats. The officials point out a porter, whom they suspect of the crimes, but upon observing him, Dornton quickly concludes that, although he drinks too heavily, he is not guilty of theft. He suggests that it is one of the students committing the robberies.

He then requests that a sofa be put into the room, as there is no closet there, and requests it be covered in chintz so that he can lie beneath it without being seen.

The sofa was brought but had a crossbeam beneath, which the sergeant broke out, giving himself room to hide lying beneath the sofa on his chest. Taking a knife, he made a peephole in the chintz. He then instructed that, when the students were all in the ward, one of the gentlemen should hang a great-coat on a peg with a pocket-book containing marked money in its pocket.

Eventually the students began to come in and out of the room, talking to one another and leaving, until at last one student, a light featured young man of approximately 22, stayed in the room until left there alone. He removed a nice hat from its peg, moving it to another peg and hung his lesser hat in its place.

Dornton felt sure he had now identified his thief, so when all the students were upstairs, he had the gentleman come in and hang the arranged great-coat. Then he proceeded to lie in wait for several hours beneath the sofa.

At last the same young man returned. He strolled through the room, whistling, then listening, then whistling again, until he began to feel in the pockets of all the hanging coats. When he came to the great-coat plant, he took the pocket-book and, rushing himself, broke the strap while putting the money in his own pocket.

At this point, the Sergeant crawled from beneath the sofa. He describes himself as quite pale and unhealthy in appearance, with a tied handkerchief around his head, so that the thief was startled by more than just his presence in the room. He identifies himself and accuses the young man, noting that he has been caught red-handed with the pocket-book and money in his possession. Unable to deny the charges, the boy pleads guilty, and while awaiting sentencing in Newgate, he takes poison and kills himself.

When asked if the time seemed long while waiting beneath the sofa, the sergeant says that had he not already identified his culprit with the hat switch, he believes the time under the sofa would have seemed long, but since he knew just who he was waiting for, the time seemed short instead.

Some Notes and Thoughts:

Some Notes and Thoughts:By referring to the hospital as “Saint Blank Hospital”, Dickens uses a common device of the time. He does not mention the hospital by name, but his readers would most likely have filled in the blank with the proper name of the hospital in question.

With no place to hide in the room, it is evidence of the quick mind of the police detective that he invents the perfect blind by having the sofa installed. He overcomes the obstacle of the crossbeam easily and shows perseverance by remaining under the sofa for such a long time.

The trap itself might seem simple, but it is very effective, for this thief cannot resist the bait which is prepared for him.

There is some humor in the image of the sergeant crawling out from under the sofa at the height of the theft. His description of himself and the thief’s reaction lighten a rather serious situation, for this is a medical student of barely 22 years in the process of ruining his life and discarding his future.

I was unable to determine who the illustrator was for this image. The image is signed, but my search came up empty. (of course, anyone (JEAN) who knows a lot about the Victorian illustrators and can identify this illustrator–the help will be welcomed.)

Dickens makes several points regarding the skills of the detectives over the criminal or the casual observer, including his ability to eliminate the suspected Porter very quickly. It is through his knowledge of human behavior that he detects that the Porter has a drinking problem but is not a thief.

The final paragraph that deals with the outcome of the case might be Dickens way of pointing out the price of immorality. The student is caught stealing from his classmates, and presumably is not a person who necessarily is in need of the money he steals, since some standing would have been necessary to be enrolled in medical school at all. Is it the guilt or the embarrassment of his situation that lead the young man to take his own life? Having this detail certainly adds some depth to the story that it would have lacked if this detail had been omitted.

Newgate Prison

Charles Dickens visited Newgate and used the infamous prison in a number of his works. It was at Newgate that he witnessed the public execution of François Benjamin Courvoisier. The hanging took place on 6 July 1840, and Charles Dickens attended with his friend and fellow writer William Makepeace Thackeray. A crowd of around 40,000 witnessed the execution. Courvoisier was a Swiss-born valet who was convicted for murdering his employer Lord William Russell and most probably the murderer of Eliza Grimwood, the subject of our first story.

It's not a Victorian illustration, but looks very like the ones produced for "Look and Learn" magazine for children and young people, in the mid 20th century. Mostly factual articles, but they did retell some of Charles Dickens's and others' stories, and the illustrators were not always credited. This style looks familiar, from ones I've seen of his novels. Well done for finding it Sara, and thanks for the interesting posts :)

I knew you would have the answer! Thank you so much, Jean. I have enjoyed the stories and doing the research. Looking forward to having others comment on this one and then seeing what Lori has up her sleeve.

I knew you would have the answer! Thank you so much, Jean. I have enjoyed the stories and doing the research. Looking forward to having others comment on this one and then seeing what Lori has up her sleeve.

I thought the anecdote was amusing, and could picture this in an old black and white TV show. I was worried that a bunch of students would sit on the sofa, and have it collapse on the detective since the crossbeam was removed. It was a good way to catch a thief for its time.

I thought the anecdote was amusing, and could picture this in an old black and white TV show. I was worried that a bunch of students would sit on the sofa, and have it collapse on the detective since the crossbeam was removed. It was a good way to catch a thief for its time.

Your research and commentary has been wonderful as you've guided us through the three anecdotes, Sara. "Three Detective Anecdotes" was an enjoyable work.

Your research and commentary has been wonderful as you've guided us through the three anecdotes, Sara. "Three Detective Anecdotes" was an enjoyable work.

In this last one, we're reminded of the seriousness of the subject matter, in the tragedy of this criminal and his suicide. I was grateful for the little comedy before the end, and loved that illustration!

In this last one, we're reminded of the seriousness of the subject matter, in the tragedy of this criminal and his suicide. I was grateful for the little comedy before the end, and loved that illustration!But I wished Dickens would have said how Dornton knew the porter wasn't responsible. It might have added a little more to the piece.

It has been a very enjoyable journey through these unusual anecdotes. Thanks so much, Sara!

Yes, it definitely struck me as sad that the criminal poisoned himself. Maybe because he was a student, I pictured him as young and foolish rather than truly sinister. And I felt sad that his life should have such an early and tragic end.

Yes, it definitely struck me as sad that the criminal poisoned himself. Maybe because he was a student, I pictured him as young and foolish rather than truly sinister. And I felt sad that his life should have such an early and tragic end.But overall, I found this story (as the other two) a fairly light and entertaining read. None of the three stories had a tremendous amount of depth, and they didn't have any long, lovely descriptive passages, but I definitely enjoyed them.

Thanks Sara for all the background info throughout!

Sara, thanks for the explanation about the hospital name. I wondered who St. Blank was and thought maybe it was a mis spelling of a French name like Blanc. But I see now it’s a very clever writer’s device.

Sara, thanks for the explanation about the hospital name. I wondered who St. Blank was and thought maybe it was a mis spelling of a French name like Blanc. But I see now it’s a very clever writer’s device. I wonder if this little story of Dickens made any Victorians think twice before sitting on a sofa, just in case someone was hiding inside :-)

I was also thinking the sofa would cause some confusion with the students with it being new to the room, but they were obviously coming in with their heads on task for the day with what they were going to learn.

I was also thinking the sofa would cause some confusion with the students with it being new to the room, but they were obviously coming in with their heads on task for the day with what they were going to learn. I enjoyed the humorous bits added by Dickens - I can only imagine the reaction of the thief when he saw the detective on his hands and knees covered with a handkerchief. He does these elements so well.

But he also is able to turn the tide and bring us back to reality with the suicide of the student. It's a horrifying end to such a young life.

Kathleen I wonder if Dickens is showing that these detectives just had a 6th sense about human nature and he saw the clues that lead him to the drinking instead. I'd also think that these detective spent a lot of time observing.

Greg I think you may get a bit more of the long descriptions you are looking for in the next detective read that starts on Monday.

Thank you to everyone for contributing to these reads! A lot of fun for me.

Thank you to everyone for contributing to these reads! A lot of fun for me.Kathleen I think Lori is right that the purpose of including the porter was to demonstrate that the detectives have developed their sense of observation to the point that they can make a determination by just observing someone that the rest of us would miss. Kind of like Sherlock Holmes always picking up on the details.

As for the suicide, I think the young man would have been so humiliated to have been caught stealing from his fellow students and so dismayed about the total loss of his future in medicine that he took this extreme measure. I think Dickens means to emphasize that actions have consequences and that the price is not worth the small monetary gains. I couldn't help thinking he was almost a kleptomaniac, since he even stooped to stealing an article of clothing--the hat.

Goodness this short anecdote has a lot of emotions - humor, fear, sorrow, relief. I like that the porter was included - that's a positive piece of marketing for the new detective force. If the hospital had fired the porter because they thought he was the thief, that would've impacted the porter in a bad way - falsely accused and fired from his job. The experience of the detectives doesn't just aid them in finding the guilty, it also protects the innocent.

Such a sad end though for that young man :( Crime does not pay.

I'll be checking under my sofa for a while after reading this LOL!

Sara thank you for putting together this great information on the early detectives and Dickens' anecdotes. Being a mystery/detective fiction lover (and a Dickens lover), I've thoroughly enjoyed myself!

Such a sad end though for that young man :( Crime does not pay.

I'll be checking under my sofa for a while after reading this LOL!

Sara thank you for putting together this great information on the early detectives and Dickens' anecdotes. Being a mystery/detective fiction lover (and a Dickens lover), I've thoroughly enjoyed myself!

Cozy It seemed as important to Dickens to show how the detective force worked for the populace as to show how they caught a criminal. Pretty important if you are trying to sell the force as something good for every man.

Cozy It seemed as important to Dickens to show how the detective force worked for the populace as to show how they caught a criminal. Pretty important if you are trying to sell the force as something good for every man.LOL. You will let us know if you find anything under the sofa, right?

So glad you enjoyed these reads. I think we have a story that will really appeal to you coming up next.

I find Dickens and the period a bit too complacent when it comes to the "punishment," of the individuals. This for me is not a criticism of Dickens but more the times. For me it is similar to others' sensitivity to animal and human cruelty and is hard to read. On transport I recommend. The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia's Founding, Robert Hughes. It tells a tortuous story for those transported. For my more issues with punishment, I recommend Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Sapolsky tries to explain behavior by explaining genetic and environmental influences on neurological origins that cause behavior.

I find Dickens and the period a bit too complacent when it comes to the "punishment," of the individuals. This for me is not a criticism of Dickens but more the times. For me it is similar to others' sensitivity to animal and human cruelty and is hard to read. On transport I recommend. The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia's Founding, Robert Hughes. It tells a tortuous story for those transported. For my more issues with punishment, I recommend Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Sapolsky tries to explain behavior by explaining genetic and environmental influences on neurological origins that cause behavior.Sara, wonderful summaries and explicative comments.

I try very hard to put myself into the times when reading, because so much of what was accepted as normal then seems egregious now. How and when to punish has been an ongoing struggle that I dare say continues to trouble us. Dickens was certainly an advocate for societal change, and helped institute much of it himself, a great example being his efforts to help "fallen women."

I try very hard to put myself into the times when reading, because so much of what was accepted as normal then seems egregious now. How and when to punish has been an ongoing struggle that I dare say continues to trouble us. Dickens was certainly an advocate for societal change, and helped institute much of it himself, a great example being his efforts to help "fallen women."Thank you for your suggestions for those who want to explore the issues further, Sam.

It's the last day on this read everyone, and we begin On Duty with Inspector Field tomorrow (Monday). Lori is leading that one (so please feel free to reserve some slots if you like, Lori!)

The eagle-eyed of you may have noticed that I had started a separate thread ready for On Duty with Inspector Field a while ago, but we all decided that the two reads fit together so logically, that it is best to keep the same thread, so that they do not get split up by the GR program over time. I'll link the second read to the first comment.

Once again, thank you so much Sara, for your fantastic leadership of this read :)

The eagle-eyed of you may have noticed that I had started a separate thread ready for On Duty with Inspector Field a while ago, but we all decided that the two reads fit together so logically, that it is best to keep the same thread, so that they do not get split up by the GR program over time. I'll link the second read to the first comment.

Once again, thank you so much Sara, for your fantastic leadership of this read :)

Today we begin the read of On Duty with Inspector Field.

Today we begin the read of On Duty with Inspector Field.The essay can be read at the following places online:

https://www.djo.org.uk/household-word...

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/872/8...

https://abrahamson.medill.northwester...

Also, it’s available in the kindle version many of us read from under the section titled “Reprinted Pieces”.

The essay was first printed in the June 14, 1851 edition of Household Words. In 1851, Dickens accompanied his friend Inspector Charles Field on a “tour” of sorts, what we’d call a ride-along today, on his nightly beat through London’s slums and crime-ridden districts. Dickens was fascinated with the business of policing and as a result of this experience wrote this essay for his magazine in order to report about his friend’s charismatic techniques on the job.

Background on Inspector Field's Career

Background on Inspector Field's Career

Charles Frederick Field spent his entire career in some form of police investigations. He initially wanted to become an actor and may have worked as an amateur, but the need for a paying job led him to join the Metropolitan Police when it was established in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel.

He may have gotten his start with the Bow Street Runners although this is not completely known. More about Bow Street Runners and the Metropolitan Police here

But with Peel’s Parliamentary Act to establish the Metropolitan Police in 1829, this group disbanded.

In September 1829, Field joined Scotland Yard in the E division (Holborn) where he rose to the position of sergeant. In just 4 years, he transferred to L division (Lambeth) and later a section of R division (Greenwich) devoted to the Woolwich Dockyards and is promoted to Inspector.

In May of 1838 Field became the lead investigator in the case of the murdered prostitute, Eliza Grimwood, see previous post here, investigating Mr. Hubbard, the woman’s cousin/boyfriend, a bricklayer who lived partly on her earnings. This case was never brought to a successful conclusion despite the fact that Inspector Field spent weeks following every lead he could. He retraced Grimwood’s steps on the eve of her death. He spent a day with a witness who testified of a possible foreign suitor visiting places and hotels in Piccadilly, Regent Circus and Leceister Square that were popular with foreigners as well as searching docks and wharfs to see if anyone had left London by steam boats matching the description of the suspect. By mid-July, investigations ceased as there was no other evidence after he spent his last days following up on anonymous letters with no luck. This case, however, proved symbiotic between the police, coroners and solicitors. Field attended the inquest daily and his investigation occurred concurrently. He used the inquest for leads and was able to provide the coroner with information. Detective Field also worked with the Grimwood’s solicitor trying to determine what to do with anonymous letters the lawyer had received.

New evidence brought the case back into the press in August of 1845 when a drunken private stumbled into a police station in Dublin claiming he had killed Eliza Grimwood. It was noted by police officials that the suspect, George Hill, was tipsy, however, he wrote a confession. When the Metropolitan Police police were notified, Field travelled to Dublin to bring the suspect to London. Two weeks later, Hill recanted his statement before the magistrate as being a drunken utterance. He had been trying to get transported having committed several crimes in order to escape “tyrannical treatment” in the army. The

In his daily reports during the investigation, Field appears defensive. He painstakingly determines to emphasize his diligence. On June 24 he wrote:

attending to several letters sent to me respecting the murder, endeavoring all in my power to find some…Evidence to bring it Home to the right persons, continually watching every movement of Hubbard to see he does not leave London and keeping myself in constant communication with persons who could in any way throw some light upon the murder.

Despite Field’s persistence in following up on every lead he could between May 26 and July 14, the murderer was not identified.

However, it appears that Field was already getting experience in his next role with the police.

The Detective Branch of the Police was established in 1842. One source claimed that due to several horrific murders (the Grimwood murder being one) not being solved, the newspapers demanded a proper detective body within the Metropolitan police force be established to investigate homicides. Up until now, police were primarily serving in the role of crime prevention and the coroner had investigated murder.

The Detective Branch consisted of two detectives affiliated with each division and two inspectors and six sergeants. This branch was a small department and its first detectives had experience investigating crimes or were believed to be able to learn quickly. Overall, detectives were more educated than the average policeman. Eventually, detectives became popular and well respected and many became household names helping to take the Met police out of the eye of public criticism. Field becomes one of the first detectives. By 1846 he is promoted to Chief of the Detective Branch serving until his retirement in 1852. Surprisingly, and rather unfortunately, there are almost no records of Inspector Field during his period of active duty.

After Field’s retirement from the police force, he set up a Private Inquiry bureau and began work as a private investigator. This was lucrative work that he claimed could earn him up to guinea a day, plus expenses for accommodations and would regularly reward him with large bonuses at the end of a case. “Up to the last trial I only received L60 or L70 from the plaintiff.” This was more than half his annual pension.

In 1856, a notorious poisoning case went to trial in which Dr. William Palmer of Rugeley was accused of poisoning a number of people including a friend and family members. The Illustrated News of the World printed a supplement devoted to the trial. The supplement described Field as “Inspector Field”, even though he was retired, implying that he was still active in the force. Field had investigated the untimely death of Walter Palmer, whom it was thought William Palmer had killed for his brother’s life insurance. But he was never called to testify during the trial.

Field often used his rank after his retirement which caused consternation with officials. The police have never hung onto rank after retirement, unlike military officers. Field’s reputation came into question and was debated during a libel trial between two newspapers. And other cases he was believed to have been a hired spy. Another case caused a temporary revocation of his pension after investigations of his conduct were held concerning a case in which he and another private detective tried to get information from the Rotterdam police through false pretenses. The revocation of pension was eventually dismissed although Field’s actions were condemned.

Field’s Friendship with Dickens

Field’s Friendship with DickensField’s relationship with Charles Dickens came about as Dickens, on occasion, would accompany the police constables on their nightly rounds. Being fascinated with the development of the force, these jaunts allowed him to get an up close look at the way the detectives worked seeing exactly the techniques they employed. As a result of his forays, the two became good friends and in 1850 Dickens wrote three articles for his journal Household Words in which he describes some of the detectives’ adventures along with character sketches, true to Dickens’ style.

In one of these A Detective Party, we have Field’s pseudonym of “Inspector Wield” and he is described as:

…a middle-aged man of portly presence, with a large, moist, knowing eye, a husky voice, and a habit of emphasising his conversation by the air of a corpulent fore-finger, which is constantly in juxta-position with his eyes or nose.

The next year, 1851, Charles Dickens wrote the essay we are reading now called On Duty With Inspector Field specifically about his work. And when Dickens began writing Bleak House in 1852, he most likely modeled Inspector Bucket after Field. The preceding description of Inspector Wield is highly suggestive of Dickens use of Field. And his contemporaries also drew the comparison repeatedly. However, Dickens never confirmed this, nor did he ever completely deny it but he wrote to ”The Times” to comment on the rumors without denying them.

In this same time period, Charles Dickens called upon his friend Inspector Field to help with a security matter for a play that Dickens was producing, directing and performing in for his friend and writer Lord Edward Bulwer Lytton. The play, “Not So Bad as We Seem”, was to be a benefit performance held at the Duke of Devonshire’s London home and with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to be among the attendees. However, no-one expected an intrusion by Lord Lytton’s estranged wife, Rosina who had intended to embarrass her husband on opening night. She wrote saying she intended to dress as a beggar girl and throw rotten eggs at her husband.

So, Charles Dickens engaged Field in order to prevent Rosina’s disruption of the play. Dickens wrote to the Duke saying

”I have spoken to Inspector Field of the Detective Police…and have requested him to attend Mr. Wills on both nights in plain clothes. He is discretion itself, and accustomed to the most delicate missions. Upon the least hint from Mr. Wills, he would show our fair correspondent the wrong way to the Theatre, and not say a word until he had her out of hearing — when he would be most polite and considerate.”

With Field’s previous involvement in amateur dramatics, it’s no surprise that he tells a lively tale with great relish. In addition to the fictionalized portrayals written by Dickens about Field, the press also made him into a celebrity as crime news grew in popularity and became a staple of reporters in the 19th century. He also enjoyed using disguises, even when not necessary. A police historian named P.T. Smith characterized this habit as “self-indulgence”. Dickens thought that Field “boasted and play[ed] to the gallery” and puffed his own image which sometimes got him in trouble.

I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. In all, you can read this under 40 minutes. I’ll use the same format that Cozy-Pug used by italicizing the last line of the reading at the end of the summary. It should be about a 10 minute read each day. Tomorrow I will post the summary for the first section. Today we can discuss anything about Inspector Field from today’s background posts.

I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. In all, you can read this under 40 minutes. I’ll use the same format that Cozy-Pug used by italicizing the last line of the reading at the end of the summary. It should be about a 10 minute read each day. Tomorrow I will post the summary for the first section. Today we can discuss anything about Inspector Field from today’s background posts.Schedule for this story -

11 - Intro and Background on Field

12-13 Summary #1 Discussion

Opening sentence - How goes the night?

Closing sentence - Both Click and Miles DO ‘hook it.’ Without another word, or, in plainer English, sneak away.

14 Free day

15-16 Summary #2 Discussion

Opening sentence - 'Close up there, my men!' says Inspector Field...

Closing sentence - ...and the power of a perfect mastery of their character, the garrison of Rat’s Castle and the adjacent Fortresses make but a skulking show indeed when reviewed by Inspector Field .

17 Free day

18-19 Summary #3 Discussion

Opening sentence - Saint Giles's clock says it will be midnight in half an hour...

Closing sentence - ...still keep a sequestered tavern, and sit o’nights smoking pipes in the bar, among ancient bottles and glasses, as our eyes behold them.

20 Free Day

21-22 Summary #4 Discussion

Opening sentence - How goes the night now?

I won't give the closing sentence because you'll be at the end of the story!

23 Free Day

24 Wrap up

Goodreads is not being kind today with posting my image of Inspector Bucket. Sara has posted his image and Jean has also posted it in the first message of this thread. I apologize and hope to correct it whenever I can. My fingers are crossed that the remaining images I've selected throughout this read will post.

Goodreads is not being kind today with posting my image of Inspector Bucket. Sara has posted his image and Jean has also posted it in the first message of this thread. I apologize and hope to correct it whenever I can. My fingers are crossed that the remaining images I've selected throughout this read will post.

Lori wrote: "I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. "

Lori wrote: "I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. "The downloadable text that I've got is just one straight read through (as in a single short story). Would it be too much trouble to ask you to provide an opening and closing sentence for each of the sections that you want to break it into?

Love the background, Lori, especially Fields' and Dickens' shared love of acting.

Love the background, Lori, especially Fields' and Dickens' shared love of acting. Fields sounds like quite an interesting character--a bit of a rogue maybe. This should be fun!

Paul wrote: "Lori wrote: "I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. "

Paul wrote: "Lori wrote: "I plan to take this story slow and break it up into 4 main reading sections. "The downloadable text that I've got is just one straight read through (as in a single short story). Woul..."

I thought about doing that Paul and would be happy to add those in. I'll add them to the schedule post if that seems like a good place to put them.

It's definitely a single short story and can be read in under 40 minutes but for the sake of the time and taking it slowly over 2 weeks as well as adding extra info and images (hopefully), I thought it would be nice to break it up.

Kathleen wrote: "Love the background, Lori, especially Fields' and Dickens' shared love of acting.

Kathleen wrote: "Love the background, Lori, especially Fields' and Dickens' shared love of acting. Fields sounds like quite an interesting character--a bit of a rogue maybe. This should be fun!"

I was quite surprised to find out Field wanted to be an actor, but what can you do, if it doesn't pay the bills?!?!? I imagine that part of his personality aided in his observation skills as a policeman and detective. When we get into the story, we might look at his interactions with the criminals as a possible stage?

It seems so typically Dickens that he would do ride-alongs with the new police force! The fact that Field and Dickens both originally wanted to be actors and then took part in amateur productions instead is super fascinating. A love for acting might explain in part why Field wore disguises, even when unnecessary.

How cool is it that detectives/inspectors were considered celebrities?! I love that - I wonder if boys (and girls) wanted to grow up and be detectives like their heroes.

The corpulent forefinger is such a distinctive physical trait - I don't think I'll ever forget that with Bucket and Field both.

Thank you, Lori for the details on Field's career and methods! He certainly seemed dedicated to solving the Eliza Grimwood case, which is admirable. I like that he cared enough about her death to do all he could to try to find the murderer.

How cool is it that detectives/inspectors were considered celebrities?! I love that - I wonder if boys (and girls) wanted to grow up and be detectives like their heroes.

The corpulent forefinger is such a distinctive physical trait - I don't think I'll ever forget that with Bucket and Field both.

Thank you, Lori for the details on Field's career and methods! He certainly seemed dedicated to solving the Eliza Grimwood case, which is admirable. I like that he cared enough about her death to do all he could to try to find the murderer.

Lori wrote: "When we get into the story, we might look at his interactions with the criminals as a possible stage?"

Ohhhh I like that idea! Now I'm imagining Field doing a very dramatic summing up scene, like Poirot! Inspector Bucket was a bit stagey in some ways, he had a great detective "patter", he had his physical trait of the emphatic fat forefinger, and climbed on a roof to look down through a skylight. That was pretty dramatic!

Thank you for mentioning this - I'll keep that angle in mind while reading the story.

Ohhhh I like that idea! Now I'm imagining Field doing a very dramatic summing up scene, like Poirot! Inspector Bucket was a bit stagey in some ways, he had a great detective "patter", he had his physical trait of the emphatic fat forefinger, and climbed on a roof to look down through a skylight. That was pretty dramatic!

Thank you for mentioning this - I'll keep that angle in mind while reading the story.

Terrific information on Field, Lori. Like others, I was struck by his sharing a love of acting with Dickens. I suspect that was one factor in making them such immediate friends.

Terrific information on Field, Lori. Like others, I was struck by his sharing a love of acting with Dickens. I suspect that was one factor in making them such immediate friends. You also mentioned, "Upon the least hint from Mr. Wills, he would show our fair correspondent the wrong way to the Theatre, and not say a word until he had her out of hearing — when he would be most polite and considerate.", which seemed to be very Bucket-like to me!

Dickens was so good at spotting personality traits and enlarging on them. I wonder what came first, Field's celebrity or Dickens' writing about him and making him one.

Great background information, Lori! When we read Bleak House I felt upset about the way fictional Mr Bucket treated Jo. I'll be curious when we read about the real Inspector Field if he was more compassionate to destitute children. (You don't have to comment on it now--I'll wait to see how the story goes.)

Great background information, Lori! When we read Bleak House I felt upset about the way fictional Mr Bucket treated Jo. I'll be curious when we read about the real Inspector Field if he was more compassionate to destitute children. (You don't have to comment on it now--I'll wait to see how the story goes.)

Cozy_Pug wrote: "It seems so typically Dickens that he would do ride-alongs with the new police force! The fact that Field and Dickens both originally wanted to be actors and then took part in amateur productions i..."

Cozy_Pug wrote: "It seems so typically Dickens that he would do ride-alongs with the new police force! The fact that Field and Dickens both originally wanted to be actors and then took part in amateur productions i..."Cozy, my research suggests that Field was completely dedicated to solving the Grimwood murder. He wasn't even a detective yet but was certainly utilizing the skills he would need when the time came a few years later for him to become a detective. I'd say he was qualified!

The press certainly added to the public's interest when the Detective Branch was established. Seems as though regardless of the time period, people can't get away from the press.

Sara wrote: "Terrific information on Field, Lori. Like others, I was struck by his sharing a love of acting with Dickens. I suspect that was one factor in making them such immediate friends.

Sara wrote: "Terrific information on Field, Lori. Like others, I was struck by his sharing a love of acting with Dickens. I suspect that was one factor in making them such immediate friends. You also mentione..."

That's a great question, Sara and the quotation you pointed out is definitely very Bucket-like. Thank you for pointing this out.

I can only surmise that the two came together to create Field's celebrity. Dickens writing about Fields and then taking traits from him to create Bucket played a big part in the public knowing who Fields was. But he was already making a name for himself in the press with his cases that the two must have worked in tandem.

I was sadly disappointed to learn that Scotland Yard has almost nothing on file in regards to Fields active duty cases unlike some of the other detectives such as Whicher.

Connie wrote: "Great background information, Lori! When we read Bleak House I felt upset about the way fictional Mr Bucket treated Jo. I'll be curious when we read about the real Inspector Field if h..."

Connie wrote: "Great background information, Lori! When we read Bleak House I felt upset about the way fictional Mr Bucket treated Jo. I'll be curious when we read about the real Inspector Field if h..."Good observation, Connie. There are some trains of thought that believe Bucket was not the nice guy cop because of his treatment of Jo. I hope the story answers the questions you have.

I'm so grateful for all this information, Lori. It looks like you did lots of research, and you presented it really well. Knowing the history of Inspector Field, how he got started, that he became a private investigator and made more money that way, that he had notoriety, will give me a lot to think about as I read this story.

I'm so grateful for all this information, Lori. It looks like you did lots of research, and you presented it really well. Knowing the history of Inspector Field, how he got started, that he became a private investigator and made more money that way, that he had notoriety, will give me a lot to think about as I read this story.And I will be picturing Dickens going with Field on his investigations, taking it all in and turning it into wonderful, entertaining stories, as he always does.

I'm glad I had not started On Duty with Inspector Field until after I read your wonderful posts!

Summary #1

Summary #1How goes the night?

It is night and St. Giles’s clock strikes nine. The weather is dull and wet and a wind blows out the pieman’s fire. A group has gathered and are punctual. They are waiting for Inspector Field to arrive. Among them is the Assistant Commissioner of Police and the Detective Sergeant. Inspector Field is currently guarding the British Museum bringing his shrewd eye to bear on every corner of its solitary galleries, before he reports ‘all right.’ He vigilantly inspects all of the rooms with his light in hand looking for any “Gonoph” or thief hiding but all is quiet.

Will Inspector Field be long about this work?

Since he will be about another half hour, he sends word by Police Constable to the others waiting by the clock to meet at St. Giles’s Station House.

Anything doing here to-night?

Not much is going on but a lost boy who is taken home, a drunken woman raving in the cells, another quiet woman with a baby at her breast sitting in the cells for begging, in another cell her husband, and in another a pickpocket, and also a meek, quivering pauper.

Presently, a sensation at the Station House door. Mr. Field, gentlemen!

He is a burly figure and asks if Rogers is ready. Rogers is strapped with a flaming eye in the middle of his waist, like a deformed Cyclops. He leads the group toward Rats’ Castle.

The narrator takes an aside to set the scene and ask:

How many people may there be in London, who, if we had brought them deviously and blindfold, to this street, fifty paces from the Station House, and within call of Saint Giles’s church, would know it for a not remote part of the city in which their lives are passed? How many, who amidst this compound of sickening smells, these heaps of filth, these tumbling houses, with all their vile contents, animate and inanimate, slimily overflowing into the black road, would believe that they breathe THIS air? How much Red Tape may there be, that could look round on the faces which now hem us in - for our appearance here has caused a rush from all points to a common centre - the lowering of foreheads, the sallow cheeks, the brutal eyes, the matted hair, the infected, vermin-haunted heaps of rags - and say, ‘I have thought of this. I have not dismissed the thing. I have neither blustered it away, nor frozen it away, nor tied it up and put it away, nor smoothly said pooh, pooh! to it when it has been shown to me?’

Rogers isn’t concerned with these questions but Rogers wants to know whether those there will clear the way for the group or be locked up. Specifically telling Bob Miles and Mister Click to hook it.

Both Click and Miles DO ‘hook it.’ Without another word, or, in plainer English, sneak away.

This ends the reading for Summary #1.

Background on St. Giles

Background on St. GilesSt. Giles has had a church on its grounds since 1101 when Queen Matilda, wife of Henry 1, founded a hospital for lepers here. The marshes and open fields in which it was built served as a barrier separating it from London hence keeping the sick at a safe distance from the wealthy. Eventually a parish, St. Giles in the Fields, grew (from Lincoln’s Inn Fields to Seven Dials and Bloomsbury) but the area wasn’t a place for respectable people and criminals saw it as a place outside of the law. In the 15th century, gallows were set up at the Churchyard gate and condemned criminals were executed. Outbreaks of the 1665 plague claimed its first victims at St. Giles with thousands buried in the graveyard.

In the 17th century, St. Giles saw some wealth but, the location attracted poor foreigners fleeing their countries, notably Irish and French. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the parishes population grew quickly creating social problems. The wealthy moved further up west and the poor congregated into congested, poverty-stricken communities. Thus, the area became one of the poorest parts of London, known as St. Giles Rookery.

The Rookery was overcrowded, densely populated and the homes were low-quality with no sanitation. The area was a maze and labyrinth of streets, lanes, courts and yards full of gin shops and secret alleyways were difficult to navigate. Thought to be one of the worst slums in Britain, St. Giles is described as a site of overcrowding and squalor, a semi-derelict warren. There were open sewers running through rooms and cesspits were neglected. Here is a complaint to the Times in 1849 by residents: We live in muck and filth. We ain’t got no priviz, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drains or suer in the hole place.”

There was a large Irish Catholic population living in the Rookery. William Hogarth, an 18th century artist, depicted the poor of St. Giles. One of his series of prints depicted the residents of ‘Little Ireland’ or ‘The Holy Land’, beggars, dissolute and depraved characters.

Gin Lane represents the drink that was thought to be the root cause of their problems. Most of those living in the Rookery survived by petty theft, begging, counterfeiting and selling goods on the streets if they weren’t landlords, publicans or shop keepers. Some were sweepers or luggage porters. Inhabitants even had their own peculiar slang language called St. Giles’ Greek. For example, Diver was a pickpocket, hearing cheats were ears, smelt was a half guinea and topping cheat was the gallows.

Most well-off Victorians were ignorant of the poor quality of life in the slums and those who were aware believed the slums were due to laziness, sin and vices of the lower class. These Victorians believed the poor had created the destitution and deprivation they found themselves in and viewed them no differently to the criminals they shared the streets with. Socially conscious writers and reformers like Charles Dickens, argued that the growth of slums were caused by poverty, unemployment, social exclusion and homelessness.

The area was filled with crime, prostitution and filth. Cadging Houses or Vagabond houses were prevalent. Thieves, prostitutes and ‘trampers’ (one night lodgers) rented rooms in these houses that were thought to breed criminality. When Dickens visited the Rookery he records <‘scenes of a most repulsive nature’, and how residents suffer ’forms bloated by disease and faces rendered hideous by habitual drunkeness’.

In 1847, the inner part of the Rookery was cleared for the New Oxford road and displaced many residents after the realization of the slums proximity to the west end. These “improvements” just forced thousands of people to cram into the surviving buildings; however, the eradication of the Rookery did not erase the poverty and deprivation. Dickens own words concerning this progress:

’thus we make our New Oxford Streets, and our other new streets, never heeding, never asking, where the wretches when we clear out, crowd.’

The Rookery doesn’t exist today, and only a few street names are recognizable. Today if you visit the area, you would find one of the most expensive shopping areas in London, an indulgent display of wealth.

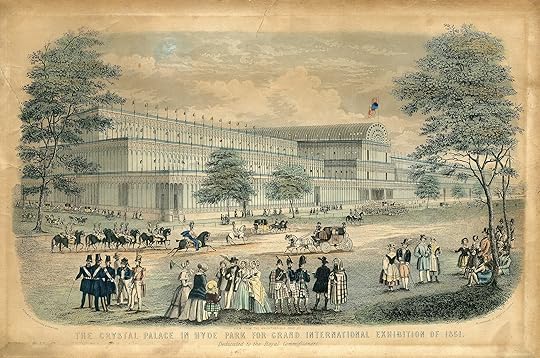

The Great Exhibition

The Great ExhibitionQueen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert is usually credited with being the driving force behind the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was housed in the ‘Crystal Palace’ in Hyde Park and brought Prince Albert’s vision to life to display the wonders of industry from all over the world. The Great Exhibition aimed to show that technology was the key to a better future, a belief that proved a motivating force behind the Industrial Revolution.

There were approximately 100,000 objects on display for more than 10 miles and over 15,000 contributors. As host, Britain occupied half the display space exhibiting such items as a massive hydraulic press, a steam-hammer, adding machines, a sportsman’s knife with 80 blades, a printing machine with quick capabilities, an expanding hearse, and a useful pulpit that connected pews with rubber tubes so that deaf parishioners could hear. These were among some of the British exhibits.

Other countries displayed their own best and most imaginative inventions. France was among the largest contributor with visually impactful and stunning displays of Limoges, tapestries, porcelain and furniture along with the machinery used to produce these objects.

Many famous people of the era attended including Queen Victoria, Charles Dickens, Michael Faraday, Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Charlotte Bronte, to name a few.

By the events end, more than 6 million people had attended.

More about the Crystal Palace:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Crys...

Some thoughts:

Some thoughts:Today we meet Inspector Fields through Dickens voice and he is really a larger than life character. He seems a bit otherworldly. He's late to meet up with them because he is at the British Museum roaming and watching for thieves hiding behind the sculptures. He's sniffing for hiding criminals with a finer scent than the ogre's.

It seems to me that Dickens wants readers to know that Field is instrumental in policing and he has authority to do so.

Lori wrote: "Most well-off Victorians were ignorant of the poor quality of life in the slums and those who were aware believed the slums were due to laziness, sin and vices of the lower class. "

Lori wrote: "Most well-off Victorians were ignorant of the poor quality of life in the slums and those who were aware believed the slums were due to laziness, sin and vices of the lower class. "I think that this is exactly the point that Dickens was making when he asked:

"How many, who amidst this compound of sickening

smells, these heaps of filth, these tumbling houses, with

all their vile contents, animate, and inanimate, slimily

overflowing into the black road, would believe that they

breathe THIS air>"

Paul wrote: "Lori wrote: "Most well-off Victorians were ignorant of the poor quality of life in the slums and those who were aware believed the slums were due to laziness, sin and vices of the lower class. "

Paul wrote: "Lori wrote: "Most well-off Victorians were ignorant of the poor quality of life in the slums and those who were aware believed the slums were due to laziness, sin and vices of the lower class. "I..."

Thank you Paul for noting how focussed Dickens was on the plight of the poor. He has begun here, right from the start of this essay to show how the wealthy viewed the poor and those living in squalor. His description is really vivid and sarcastic. I was glad to see this side of Dickens come through here.

Books mentioned in this topic

Bleak House (other topics)A Study in Scarlet (other topics)

Little Dorrit (other topics)

Rookeries of London (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Anthony Trollope (other topics)

Horace Walpole (other topics)

Anthony Trollope (other topics)

More...

You could be transported for stealing a piece of fruit in the market, even if you were starving. The previous century people were hanged for this. It's a recurring theme in Charles Dickens's stories.

Charles Dickens often includes something in his novels about transportation, often for criminals but also to start a new life! It seems odd that Britain exported both convicts and those seeking new opportunities in life, to the same place, but it was thought that the climate was good, and there would be plenty of prospects.

Charles Dickens also wrote about the transport of convicts to America, even though that had stopped in 1776. After then they were sent to Australia. From 1788 to 1868 Britain transported more than 160,000 convicts from its overcrowded prisons to the Australian colonies, forming the basis of the first migration from Europe to Australia. It is estimated that 140,000 criminals were transported to Australia between 1810 and 1852. It was for life, and if a convict ever returned to Britain, they were hanged (by law, until 1834), even though the original offences were sometimes quite minor by modern standards.

Charles Dickens himself was very keen on emigrating, and even strongly encouraged two of his sons to go there. Alfred emigrated in 1865 and Edward ("Plorn") in 1868. He wrote about emigration in his newspaper "Household Words". And in 1848, the journalist Samuel Sidney produced an Australian "Handbook" which recommended emigration of the working-class, because of the agricultural life in Australia. This was successful, and it was "a land of opportunity".

Evidently Charles Dickens's attitude to emigration was conflicted; he was ambivalent about emigration, approving the concept both for his own sons, and characters in his novels, yet also writing a lot about the transportation of criminals.