The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit, Book 2, Chp. 01-04

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

The second chapter is relatively short and it gives us some background information on “Mrs. General” and on how she became a member of the Dorrit family. It also provides some comic relief after the portentous and alarming atmosphere of the preceding chapter.

”Mrs General was the daughter of a clerical dignitary in a cathedral town, where she had led the fashion until she was as near forty-five as a single lady can be.”

In the same rather snappy vein we are told that Mrs. General married late and was a model of propriety and manners, and that her husband matched her well on these two heads. After his early death, however, she had to find out that her financial situation was less promising than she had anticipated since her husband had bought himself an annuity rather than possess ample means, and after his death the annuity was forfeited. She then had the idea of becoming a kind of tutor, governess and chaperon to a young lady, and for seven years she worked in that position for a widower and his daughter. This daughter finally being married, Mrs. General’s services were back on the market, and Mr. Dorrit learned through his bankers that Mrs. General is just the sort of person that might be adequate for his own daughters. It is quite funny how the narrator explains how someone like Mrs. General usually gets the best of testimonials:

”Mrs General's communication of this idea to her clerical and commissariat connection was so warmly applauded that, but for the lady's undoubted merit, it might have appeared as though they wanted to get rid of her. Testimonials representing Mrs General as a prodigy of piety, learning, virtue, and gentility, were lavishly contributed from influential quarters; and one venerable archdeacon even shed tears in recording his testimony to her perfections (described to him by persons on whom he could rely), though he had never had the honour and moral gratification of setting eyes on Mrs General in all his life.”

”The widower then finding Mrs General both inconvenient and expensive, became of a sudden almost as much affected by her merits as the archdeacon had been, and circulated such praises of her surpassing worth, in all quarters where he thought an opportunity might arise of transferring the blessing to somebody else, that Mrs General was a name more honourable than ever.”

This is probably the way people rise to the highest positions in Barnacle County. Mrs. General is very sensitive with regard to her position in that she can only accept to be treated as a member of her employer’s family, and not as an employee, and, of course, money is a subject that is not to be touched on with her – and yet she manages to increase her – extremely generous – salary by a third when she enters into Mr. Dorrit’s services.

We also learn this of her:

”In person, Mrs General, including her skirts which had much to do with it, was of a dignified and imposing appearance; ample, rustling, gravely voluminous; always upright behind the proprieties. She might have been taken—had been taken—to the top of the Alps and the bottom of Herculaneum, without disarranging a fold in her dress, or displacing a pin. If her countenance and hair had rather a floury appearance, as though from living in some transcendently genteel Mill, it was rather because she was a chalky creation altogether, than because she mended her complexion with violet powder, or had turned grey. If her eyes had no expression, it was probably because they had nothing to express. If she had few wrinkles, it was because her mind had never traced its name or any other inscription on her face. A cool, waxy, blown-out woman, who had never lighted well.

Mrs General had no opinions. Her way of forming a mind was to prevent it from forming opinions. She had a little circular set of mental grooves or rails on which she started little trains of other people's opinions, which never overtook one another, and never got anywhere. Even her propriety could not dispute that there was impropriety in the world; but Mrs General's way of getting rid of it was to put it out of sight, and make believe that there was no such thing. This was another of her ways of forming a mind—to cram all articles of difficulty into cupboards, lock them up, and say they had no existence. It was the easiest way, and, beyond all comparison, the properest.

Mrs General was not to be told of anything shocking. Accidents, miseries, and offences, were never to be mentioned before her. Passion was to go to sleep in the presence of Mrs General, and blood was to change to milk and water. The little that was left in the world, when all these deductions were made, it was Mrs General's province to varnish. In that formation process of hers, she dipped the smallest of brushes into the largest of pots, and varnished the surface of every object that came under consideration. The more cracked it was, the more Mrs General varnished it.

There was varnish in Mrs General's voice, varnish in Mrs General's touch, an atmosphere of varnish round Mrs General's figure. Mrs General's dreams ought to have been varnished—if she had any—lying asleep in the arms of the good Saint Bernard, with the feathery snow falling on his house-top.”

I don’t really know what function this chapter has in the context of the novel – maybe Mrs. General, who is rather a late-comer in the dramatis personae of this novel, is going to play an important role yet –, but I could not help feeling reminded of good old Mrs. Sparsit here.

”Mrs General was the daughter of a clerical dignitary in a cathedral town, where she had led the fashion until she was as near forty-five as a single lady can be.”

In the same rather snappy vein we are told that Mrs. General married late and was a model of propriety and manners, and that her husband matched her well on these two heads. After his early death, however, she had to find out that her financial situation was less promising than she had anticipated since her husband had bought himself an annuity rather than possess ample means, and after his death the annuity was forfeited. She then had the idea of becoming a kind of tutor, governess and chaperon to a young lady, and for seven years she worked in that position for a widower and his daughter. This daughter finally being married, Mrs. General’s services were back on the market, and Mr. Dorrit learned through his bankers that Mrs. General is just the sort of person that might be adequate for his own daughters. It is quite funny how the narrator explains how someone like Mrs. General usually gets the best of testimonials:

”Mrs General's communication of this idea to her clerical and commissariat connection was so warmly applauded that, but for the lady's undoubted merit, it might have appeared as though they wanted to get rid of her. Testimonials representing Mrs General as a prodigy of piety, learning, virtue, and gentility, were lavishly contributed from influential quarters; and one venerable archdeacon even shed tears in recording his testimony to her perfections (described to him by persons on whom he could rely), though he had never had the honour and moral gratification of setting eyes on Mrs General in all his life.”

”The widower then finding Mrs General both inconvenient and expensive, became of a sudden almost as much affected by her merits as the archdeacon had been, and circulated such praises of her surpassing worth, in all quarters where he thought an opportunity might arise of transferring the blessing to somebody else, that Mrs General was a name more honourable than ever.”

This is probably the way people rise to the highest positions in Barnacle County. Mrs. General is very sensitive with regard to her position in that she can only accept to be treated as a member of her employer’s family, and not as an employee, and, of course, money is a subject that is not to be touched on with her – and yet she manages to increase her – extremely generous – salary by a third when she enters into Mr. Dorrit’s services.

We also learn this of her:

”In person, Mrs General, including her skirts which had much to do with it, was of a dignified and imposing appearance; ample, rustling, gravely voluminous; always upright behind the proprieties. She might have been taken—had been taken—to the top of the Alps and the bottom of Herculaneum, without disarranging a fold in her dress, or displacing a pin. If her countenance and hair had rather a floury appearance, as though from living in some transcendently genteel Mill, it was rather because she was a chalky creation altogether, than because she mended her complexion with violet powder, or had turned grey. If her eyes had no expression, it was probably because they had nothing to express. If she had few wrinkles, it was because her mind had never traced its name or any other inscription on her face. A cool, waxy, blown-out woman, who had never lighted well.

Mrs General had no opinions. Her way of forming a mind was to prevent it from forming opinions. She had a little circular set of mental grooves or rails on which she started little trains of other people's opinions, which never overtook one another, and never got anywhere. Even her propriety could not dispute that there was impropriety in the world; but Mrs General's way of getting rid of it was to put it out of sight, and make believe that there was no such thing. This was another of her ways of forming a mind—to cram all articles of difficulty into cupboards, lock them up, and say they had no existence. It was the easiest way, and, beyond all comparison, the properest.

Mrs General was not to be told of anything shocking. Accidents, miseries, and offences, were never to be mentioned before her. Passion was to go to sleep in the presence of Mrs General, and blood was to change to milk and water. The little that was left in the world, when all these deductions were made, it was Mrs General's province to varnish. In that formation process of hers, she dipped the smallest of brushes into the largest of pots, and varnished the surface of every object that came under consideration. The more cracked it was, the more Mrs General varnished it.

There was varnish in Mrs General's voice, varnish in Mrs General's touch, an atmosphere of varnish round Mrs General's figure. Mrs General's dreams ought to have been varnished—if she had any—lying asleep in the arms of the good Saint Bernard, with the feathery snow falling on his house-top.”

I don’t really know what function this chapter has in the context of the novel – maybe Mrs. General, who is rather a late-comer in the dramatis personae of this novel, is going to play an important role yet –, but I could not help feeling reminded of good old Mrs. Sparsit here.

Chapter 3 sees our fellow travellers “On the Road” again when they all prepare to resume their respective journeys on the following morning. Mr. Tip has a little conversation with his sister Amy, in which he once more expresses his contempt for Mr. Gowan – nevertheless, he seems too much of a coward to do this in Gowan’s own face –, and then he also warns Amy not to fall back into her old habits and start nursing Mrs. Gowan herself. In fact, the Dorrits, who used to depend so much on Amy’s unwavering kindness, now seem to feel quite ashamed of her, as the following extract might show:

”’I have only been in to ask her if I could do anything for her, Tip,’ said Little Dorrit.

‘You needn't call me Tip, Amy child,’ returned that young gentleman with a frown; ‘because that's an old habit, and one you may as well lay aside.’

‘I didn't mean to say so, Edward dear. I forgot. It was so natural once, that it seemed at the moment the right word.’

‘Oh yes!’ Miss Fanny struck in. ‘Natural, and right word, and once, and all the rest of it! Nonsense, you little thing! I know perfectly well why you have been taking such an interest in this Mrs Gowan. You can't blind me.’

‘I will not try to, Fanny. Don't be angry.’

‘Oh! angry!’ returned that young lady with a flounce. ‘I have no patience’ (which indeed was the truth).

‘Pray, Fanny,’ said Mr Dorrit, raising his eyebrows, ‘what do you mean? Explain yourself.’”

Fanny now explains to her father that Amy’s interest in Mrs. Gowan might have something to do with her acquaintance with Arthur Clennam, and in the course of the ensuing conversation it becomes clear that Mr. Dorrit, in the splendour of his newly-gained dignity and importance, has deemed it best not to prolong his acquaintance with Mr. Clennam as the latter presents a link with a past the Dorrits would like to forget. Mr. Dorrit has shown his gratitude to the Plornishes by buying them a little business – it is not said of what kind – but still any memory of his former life and any contact with those who in some way or other shared it with him would be unbearable to the Dorrits, at least to the former Father of the Marshalsea and his two elder children. Consequently, they all tend to look down a bit on Amy for not being ready to cast off old – and good – habits. The only family member, who shows more and more awareness of Amy’s good qualities and who cannot see her slighted by anyone is Frederick Dorrit, who is still living in a world of his own but nevertheless aware of when his youngest niece is treated inconsiderately by her family or their servants.

After breakfast, the Dorrits and their suite get ready for departure, and on their way down the mountain, Amy feels Mr. Blandois watching her – again, I can well imagine this scene in a film noir, with Blandois taken from a low-angle shot, black against a clear sky, and then a zoom-out centred on his solitary figure against the sky, and maybe a dissolving cut showing Amy’s pupil in which the image of that solitary figure lingers:

”Nevertheless, as they wound down the rugged way while the convent was yet in sight, she more than once looked round, and descried Mr Blandois, backed by the convent smoke which rose straight and high from the chimneys in a golden film, always standing on one jutting point looking down after them. Long after he was a mere black stick in the snow, she felt as though she could yet see that smile of his, that high nose, and those eyes that were too near it. And even after that, when the convent was gone and some light morning clouds veiled the pass below it, the ghastly skeleton arms by the wayside seemed to be all pointing up at him.

More treacherous than snow, perhaps, colder at heart, and harder to melt, Blandois of Paris by degrees passed out of her mind, as they came down into the softer regions.”

When the family arrive at Martigny, they find, to Mr. Dorrit’s dismay, that one room of their suite has been given to a lady and her son to have breakfast in. Where a more self-confident person would have been able to let it go, Mr. Dorrit feels that his honour has been slighted and he tells the abject landlord that he will never again set a foot into his hotel. The narrator has a fine psychological eye with regard to upstart sensibilities:

”He felt that the family dignity was struck at by an assassin's hand. He had a sense of his dignity, which was of the most exquisite nature. He could detect a design upon it when nobody else had any perception of the fact. His life was made an agony by the number of fine scalpels that he felt to be incessantly engaged in dissecting his dignity.”

Accidentally, however, the lady in question and her son prove to be Mrs. Merdle and her son Edmund Sparkler, who knows Edward Dorrit quite well, and consequently the conflict is eventually patched up – much to the gratification of Fanny, who is now able to confront Mrs. Merdle in a more elevated social position.

The chapter closes with some observations on how lonely Amy feels, on how she would like to be once again close to her father and be able to show her caring nature. All this, however, seems to belong to the past, which was, paradoxically, a happier time for Amy than the family’s rise to fortune has brought.

I was thinking what to make of Mr. Dorrit’s unwillingness to keep the past alive, or rather his willingness to forget about it – and must say that to a certain extent I can understand him: He might have had quite a lot of traumatic experiences in that prison, especially in his first years there, and so it is only natural that he does not want to be reminded of it. And yet, it is not only that but also a lot of vanity and pomposity that make the Dorrits behave the way they do, isn’t it? Their thanklessness against Amy is as annoying to me as Amy’s humility and eagerness to please when she is faced with the snobbery of her siblings and her father.

”’I have only been in to ask her if I could do anything for her, Tip,’ said Little Dorrit.

‘You needn't call me Tip, Amy child,’ returned that young gentleman with a frown; ‘because that's an old habit, and one you may as well lay aside.’

‘I didn't mean to say so, Edward dear. I forgot. It was so natural once, that it seemed at the moment the right word.’

‘Oh yes!’ Miss Fanny struck in. ‘Natural, and right word, and once, and all the rest of it! Nonsense, you little thing! I know perfectly well why you have been taking such an interest in this Mrs Gowan. You can't blind me.’

‘I will not try to, Fanny. Don't be angry.’

‘Oh! angry!’ returned that young lady with a flounce. ‘I have no patience’ (which indeed was the truth).

‘Pray, Fanny,’ said Mr Dorrit, raising his eyebrows, ‘what do you mean? Explain yourself.’”

Fanny now explains to her father that Amy’s interest in Mrs. Gowan might have something to do with her acquaintance with Arthur Clennam, and in the course of the ensuing conversation it becomes clear that Mr. Dorrit, in the splendour of his newly-gained dignity and importance, has deemed it best not to prolong his acquaintance with Mr. Clennam as the latter presents a link with a past the Dorrits would like to forget. Mr. Dorrit has shown his gratitude to the Plornishes by buying them a little business – it is not said of what kind – but still any memory of his former life and any contact with those who in some way or other shared it with him would be unbearable to the Dorrits, at least to the former Father of the Marshalsea and his two elder children. Consequently, they all tend to look down a bit on Amy for not being ready to cast off old – and good – habits. The only family member, who shows more and more awareness of Amy’s good qualities and who cannot see her slighted by anyone is Frederick Dorrit, who is still living in a world of his own but nevertheless aware of when his youngest niece is treated inconsiderately by her family or their servants.

After breakfast, the Dorrits and their suite get ready for departure, and on their way down the mountain, Amy feels Mr. Blandois watching her – again, I can well imagine this scene in a film noir, with Blandois taken from a low-angle shot, black against a clear sky, and then a zoom-out centred on his solitary figure against the sky, and maybe a dissolving cut showing Amy’s pupil in which the image of that solitary figure lingers:

”Nevertheless, as they wound down the rugged way while the convent was yet in sight, she more than once looked round, and descried Mr Blandois, backed by the convent smoke which rose straight and high from the chimneys in a golden film, always standing on one jutting point looking down after them. Long after he was a mere black stick in the snow, she felt as though she could yet see that smile of his, that high nose, and those eyes that were too near it. And even after that, when the convent was gone and some light morning clouds veiled the pass below it, the ghastly skeleton arms by the wayside seemed to be all pointing up at him.

More treacherous than snow, perhaps, colder at heart, and harder to melt, Blandois of Paris by degrees passed out of her mind, as they came down into the softer regions.”

When the family arrive at Martigny, they find, to Mr. Dorrit’s dismay, that one room of their suite has been given to a lady and her son to have breakfast in. Where a more self-confident person would have been able to let it go, Mr. Dorrit feels that his honour has been slighted and he tells the abject landlord that he will never again set a foot into his hotel. The narrator has a fine psychological eye with regard to upstart sensibilities:

”He felt that the family dignity was struck at by an assassin's hand. He had a sense of his dignity, which was of the most exquisite nature. He could detect a design upon it when nobody else had any perception of the fact. His life was made an agony by the number of fine scalpels that he felt to be incessantly engaged in dissecting his dignity.”

Accidentally, however, the lady in question and her son prove to be Mrs. Merdle and her son Edmund Sparkler, who knows Edward Dorrit quite well, and consequently the conflict is eventually patched up – much to the gratification of Fanny, who is now able to confront Mrs. Merdle in a more elevated social position.

The chapter closes with some observations on how lonely Amy feels, on how she would like to be once again close to her father and be able to show her caring nature. All this, however, seems to belong to the past, which was, paradoxically, a happier time for Amy than the family’s rise to fortune has brought.

I was thinking what to make of Mr. Dorrit’s unwillingness to keep the past alive, or rather his willingness to forget about it – and must say that to a certain extent I can understand him: He might have had quite a lot of traumatic experiences in that prison, especially in his first years there, and so it is only natural that he does not want to be reminded of it. And yet, it is not only that but also a lot of vanity and pomposity that make the Dorrits behave the way they do, isn’t it? Their thanklessness against Amy is as annoying to me as Amy’s humility and eagerness to please when she is faced with the snobbery of her siblings and her father.

In the fourth chapter we get “A Letter from Little Dorrit”, which is addressed to Mr. Clennam. As the letter is relatively short – not for a letter, but for a chapter –, my recap can be relatively short, too. Among other things, e.g. the fact that the Plornishes’ business is flourishing and that Mr. Nandy is now able to live with his family, Amy tells Clennam that she has met Mrs. Gowan and that the young lady is tolerably well. She also says this about Mrs. Gowan’s husband:

”It will not make you uneasy on Mrs Gowan's account, I hope—for I remember that you said you had the interest of a true friend in her—if I tell you that I wish she could have married some one better suited to her. Mr Gowan seems fond of her, and of course she is very fond of him, but I thought he was not earnest enough—I don't mean in that respect—I mean in anything. I could not keep it out of my mind that if I was Mrs Gowan (what a change that would be, and how I must alter to become like her!) I should feel that I was rather lonely and lost, for the want of some one who was steadfast and firm in purpose. I even thought she felt this want a little, almost without knowing it. But mind you are not made uneasy by this, for she was 'very well and very happy.' And she looked most beautiful.“

She goes on by describing her new life, giving the following very moving account:

”It is the same with all these new countries and wonderful sights. They are very beautiful, and they astonish me, but I am not collected enough—not familiar enough with myself, if you can quite understand what I mean—to have all the pleasure in them that I might have. What I knew before them, blends with them, too, so curiously. For instance, when we were among the mountains, I often felt (I hesitate to tell such an idle thing, dear Mr Clennam, even to you) as if the Marshalsea must be behind that great rock; or as if Mrs Clennam's room where I have worked so many days, and where I first saw you, must be just beyond that snow. Do you remember one night when I came with Maggy to your lodging in Covent Garden? That room I have often and often fancied I have seen before me, travelling along for miles by the side of our carriage, when I have looked out of the carriage-window after dark. We were shut out that night, and sat at the iron gate, and walked about till morning. I often look up at the stars, even from the balcony of this room, and believe that I am in the street again, shut out with Maggy. It is the same with people that I left in England.

When I go about here in a gondola, I surprise myself looking into other gondolas as if I hoped to see them. It would overcome me with joy to see them, but I don't think it would surprise me much, at first. In my fanciful times, I fancy that they might be anywhere; and I almost expect to see their dear faces on the bridges or the quays.

Another difficulty that I have will seem very strange to you. It must seem very strange to any one but me, and does even to me: I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him. Changed as he is, and inexpressibly blest and thankful as I always am to know it, the old sorrowful feeling of compassion comes upon me sometimes with such strength that I want to put my arms round his neck, tell him how I love him, and cry a little on his breast. I should be glad after that, and proud and happy. But I know that I must not do this; that he would not like it, that Fanny would be angry, that Mrs General would be amazed; and so I quiet myself. Yet in doing so, I struggle with the feeling that I have come to be at a distance from him; and that even in the midst of all the servants and attendants, he is deserted, and in want of me.”

Finally, she signs her letter with the words “Your poor child, Little Dorrit”, which did not go down too well with me because I asked myself why a grown-up woman should talk about herself as a child.

”It will not make you uneasy on Mrs Gowan's account, I hope—for I remember that you said you had the interest of a true friend in her—if I tell you that I wish she could have married some one better suited to her. Mr Gowan seems fond of her, and of course she is very fond of him, but I thought he was not earnest enough—I don't mean in that respect—I mean in anything. I could not keep it out of my mind that if I was Mrs Gowan (what a change that would be, and how I must alter to become like her!) I should feel that I was rather lonely and lost, for the want of some one who was steadfast and firm in purpose. I even thought she felt this want a little, almost without knowing it. But mind you are not made uneasy by this, for she was 'very well and very happy.' And she looked most beautiful.“

She goes on by describing her new life, giving the following very moving account:

”It is the same with all these new countries and wonderful sights. They are very beautiful, and they astonish me, but I am not collected enough—not familiar enough with myself, if you can quite understand what I mean—to have all the pleasure in them that I might have. What I knew before them, blends with them, too, so curiously. For instance, when we were among the mountains, I often felt (I hesitate to tell such an idle thing, dear Mr Clennam, even to you) as if the Marshalsea must be behind that great rock; or as if Mrs Clennam's room where I have worked so many days, and where I first saw you, must be just beyond that snow. Do you remember one night when I came with Maggy to your lodging in Covent Garden? That room I have often and often fancied I have seen before me, travelling along for miles by the side of our carriage, when I have looked out of the carriage-window after dark. We were shut out that night, and sat at the iron gate, and walked about till morning. I often look up at the stars, even from the balcony of this room, and believe that I am in the street again, shut out with Maggy. It is the same with people that I left in England.

When I go about here in a gondola, I surprise myself looking into other gondolas as if I hoped to see them. It would overcome me with joy to see them, but I don't think it would surprise me much, at first. In my fanciful times, I fancy that they might be anywhere; and I almost expect to see their dear faces on the bridges or the quays.

Another difficulty that I have will seem very strange to you. It must seem very strange to any one but me, and does even to me: I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him. Changed as he is, and inexpressibly blest and thankful as I always am to know it, the old sorrowful feeling of compassion comes upon me sometimes with such strength that I want to put my arms round his neck, tell him how I love him, and cry a little on his breast. I should be glad after that, and proud and happy. But I know that I must not do this; that he would not like it, that Fanny would be angry, that Mrs General would be amazed; and so I quiet myself. Yet in doing so, I struggle with the feeling that I have come to be at a distance from him; and that even in the midst of all the servants and attendants, he is deserted, and in want of me.”

Finally, she signs her letter with the words “Your poor child, Little Dorrit”, which did not go down too well with me because I asked myself why a grown-up woman should talk about herself as a child.

Aw, come on - you never heard a silly woman play like a child to her intended -- You sweet thing, beg me, tell me how wonderful I am. Or I will tell you how wonderful you are. d And you can bring gifts, too.

Aw, come on - you never heard a silly woman play like a child to her intended -- You sweet thing, beg me, tell me how wonderful I am. Or I will tell you how wonderful you are. d And you can bring gifts, too. Please, sweet Tristam, keep giving us wonderful unbiased sweet reviews. Don't quit us now, honey baby, we need you (magic words) to keep giving us info. pleaseeeeessssse. much love and peace, janz

p.s. I am somewhat grown up, only 78 years old.

Janz, I had to laugh out loud from your comment for a moment. Thank you. And indeed, there are women like this who - on purpose, or not - make themselves look like they need a strong man to guide them, and it appeals to a certain type of man. I do think Arthur Clennam is that kind of man, and I think Dickens might have been that kind of man too. After all, he really likes to paint his heroines like helpless, meek little womenfolk who need the strong, women saving Nice Guy™ to rescue them.

Also I love how the Dorrits are dislikeable as ever. They behave exactly in a way that they would fit into the mold of those Karen-memes. People like this are of all times and places, and I like how Dickens makes us dig deeper than the memes make us do nowadays - he shows us that there is more to it than just being mean, that it is a combination of that with gross insecurity and in the Dorrits' case probably some trauma from earlier years. No one thinks 'let's become a person like that', somehow it happens to happen.

In their current circumstances, the Dorrits remind me of one of my favorite TV characters, Hyacinth Bucket (that's "Bouquet"!) from Keeping Up Appearances. She's so concerned about what everyone thinks of her, never realizing how foolish all her superior airs make her look to everyone she encounters. Unlike the Dorrits, though, Hyacinth is a comedic character because those in her orbit see her the same way we do; no one takes her seriously.

In their current circumstances, the Dorrits remind me of one of my favorite TV characters, Hyacinth Bucket (that's "Bouquet"!) from Keeping Up Appearances. She's so concerned about what everyone thinks of her, never realizing how foolish all her superior airs make her look to everyone she encounters. Unlike the Dorrits, though, Hyacinth is a comedic character because those in her orbit see her the same way we do; no one takes her seriously. I think Tristram and Jantine are both correct. The Dorrits' behavior is a mixture of pomposity (mostly Tip and Fanny) and severe insecurity (Mr. Dorrit). I don't think their shunning Clennam is to lock out past traumas so much as they're afraid he might reveal their secret. Mr. Dorrit will go through life now, looking over his shoulder, wondering when his shameful past might catch up with him. Do Mrs. Merdle and Sparkler know about Fanny's family, or are they in the dark about her father's prison time?

Tristram wrote: [Pet] begs Amy to take back the paper lest her husband should find it on her...

This was an offhand remark, but struck me as being rather ominous. Has the memory of Arthur come between Pet and Gowan (and does he call her Pet or Minnie, I wonder)?

Mrs. General/Mrs. Sparsit - very interesting comparison! We must keep an eye on Mrs. General. Will she be a trouble maker? I'd like to see her interact with Mrs. Merdle, as I suspect they both have "capital bosoms." :-)

Oh, I looked over that here, but I indeed was reminded of Mrs. Sparsit too! We certainly must keep an eye on Mrs. General.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

This week we have finally arrived at the second Part of the novel, which is called “Riches” and which sees the Dorrit family in greatly altered circumstances. Chapter 1 of this se..."

Yes. I think the use of the word lasso has many far-reaching suggestions and consequences. Blandois has entered into the lives of the Dorrit’s, both Arthur Clennam and his mother, and Miss Wade. A lasso is meant to capture and confine another person. Who, how, and when might Blandois encircle others remains to be seen.

The opening paragraphs of this chapter has the feeling of space, openness and fresh air. After our experiences in Book One where we encountered the confines of a jail, the dark serpentine nature of the streets, the claustrophobic crumbling house of Mrs Clennam, and the teaming humanity of Bleeding Heart Yard we are now in the open air, the freshness of the country and the comfort of a traveller’s inn. Dickens loves presenting contrasting characters to his readers; here is an example of contrasting settings.

Even with this contrast, however, we still feel the underlying current of the major motif of imprisonment. If we look at the last words of the chapter we read “Then, with his nose coming down over his moustache and his moustache going up and under his nose, [Blandois] repaired to his allotted cell.” The word “cell” has much significance. In Chapter One of Book One we encountered Blandois (then called Rigaud) in jail. Here he is encountered in the first chapter of Book Two and is his room is called a “cell.”

Chapter Two of Book One is titled “Fellow Travellers.” Chapter One of Book Two is titled “Fellow Travellers.” Is this a coincidence or should we pause for a moment and wonder what the implications could be?

This week we have finally arrived at the second Part of the novel, which is called “Riches” and which sees the Dorrit family in greatly altered circumstances. Chapter 1 of this se..."

Yes. I think the use of the word lasso has many far-reaching suggestions and consequences. Blandois has entered into the lives of the Dorrit’s, both Arthur Clennam and his mother, and Miss Wade. A lasso is meant to capture and confine another person. Who, how, and when might Blandois encircle others remains to be seen.

The opening paragraphs of this chapter has the feeling of space, openness and fresh air. After our experiences in Book One where we encountered the confines of a jail, the dark serpentine nature of the streets, the claustrophobic crumbling house of Mrs Clennam, and the teaming humanity of Bleeding Heart Yard we are now in the open air, the freshness of the country and the comfort of a traveller’s inn. Dickens loves presenting contrasting characters to his readers; here is an example of contrasting settings.

Even with this contrast, however, we still feel the underlying current of the major motif of imprisonment. If we look at the last words of the chapter we read “Then, with his nose coming down over his moustache and his moustache going up and under his nose, [Blandois] repaired to his allotted cell.” The word “cell” has much significance. In Chapter One of Book One we encountered Blandois (then called Rigaud) in jail. Here he is encountered in the first chapter of Book Two and is his room is called a “cell.”

Chapter Two of Book One is titled “Fellow Travellers.” Chapter One of Book Two is titled “Fellow Travellers.” Is this a coincidence or should we pause for a moment and wonder what the implications could be?

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 3 sees our fellow travellers “On the Road” again when they all prepare to resume their respective journeys on the following morning. Mr. Tip has a little conversation with his sister Amy, i..."

Question for everyone. Is Dorrit’s kindness to the Plornish’s the only action he has done that is not self-serving or all about himself?

Both Tip and Fanny seem to be enjoying the wealth and newly founded social positions. They set their sights on Arthur who is now clearly beneath their new social position. Meanwhile, Amy looks back fondly on the old days when she was locked out of the Marshalsea with Maggy. Money has intensified the earlier characteristics of Tip and Fanny. I imagine money will continue to define this family.

Question for everyone. Is Dorrit’s kindness to the Plornish’s the only action he has done that is not self-serving or all about himself?

Both Tip and Fanny seem to be enjoying the wealth and newly founded social positions. They set their sights on Arthur who is now clearly beneath their new social position. Meanwhile, Amy looks back fondly on the old days when she was locked out of the Marshalsea with Maggy. Money has intensified the earlier characteristics of Tip and Fanny. I imagine money will continue to define this family.

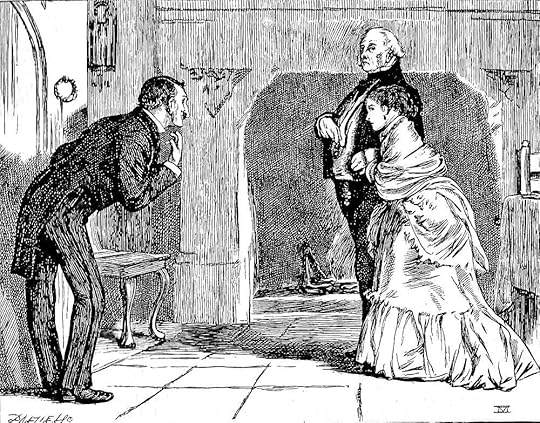

The Travellers

Chapter 1, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"You, madam," said the insinuating traveller, "have visited this spot before?"

"Yes," returned Mrs. General. "I have been here before. Let me commend you, my dear," to the former young lady, "to shade your face from the hot wood, after exposure to the mountain air and snow. You, too, my dear," to the other and younger lady, who immediately did so; while the former merely said, "Thank you, Mrs. General, I am perfectly comfortable, and prefer remaining as I am."

The brother, who had left his chair to open a piano that stood in the room, and who had whistled into it and shut it up again, now came strolling back to the fire with his glass in his eye. He was dressed in the very fullest and completest travelling trim. The world seemed hardly large enough to yield him an amount of travel proportionate to his equipment.

"These fellows are an immense time with supper," he drawled. "I wonder what they'll give us! Has anybody any idea?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 1, "Fellow-Travellers,".

Commentary:

The drawing technique is characteristic of Browne's style in the late 1850s and early 1860s at its best, with a concern for composition, a pleasant handling of faces, and something of a sparseness of background details. In some of these plates, however, there is a tendency toward excessively rigid symmetry, as in the very next one in this novel, "The Travellers" (Bk. 2, ch. 1).

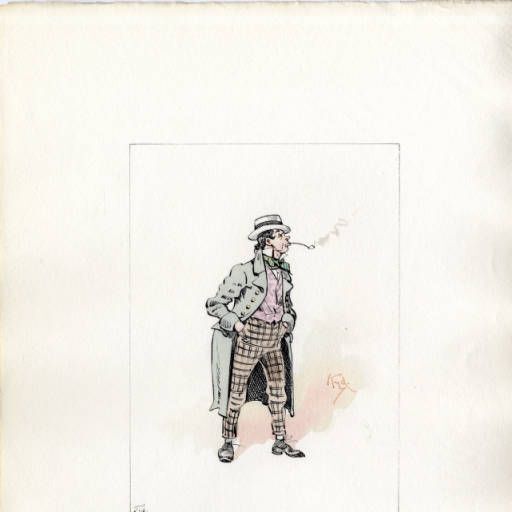

The symmetry which Steig contends imposes a rigid organization upon the composition is consistent with Dickens's description of the three "parties" waiting for their dinner in the parlor of the Alpine convent. The "insinuating traveller" is almost certainly Monsieur Blandois (extreme left, smoking) in the first chapter of the October 1856 (eleventh) instalment that marks the mid-point of the serial run. "The Chief" (William Dorrit) and his suite — his brother Frederick, his daughters Amy and Fanny, and their governess, Mrs. General, occupy the right-hand side, with Tip Dorrit in the rather loud suit and sporting a monocle, immediately before the fire, "roasting" himself. Aside from Blandois, already noted, the left-hand register includes Minnie and Henry Gowan ("the artist traveller," nearest the viewer, to whom Blandois has already attached himself), and the overtaking party whom Dickens explicitly describes: "The third party, which had ascended from the valley on the Italian side of the Pass, and had arrived first, were four in number: a plethoric, hungry, and silent German tutor in spectacles, on a tour with three young men, his pupils, all plethoric, hungry, and silent, and all in spectacles". A "value-added" feature in the drawing of the international travelers is that Mrs. General's fan, not mentioned in the letterpress, forms a kind of halo around Amy Dorrit's head, right. To suggest that the setting is the refectory of a convent, Phiz has added a statue of the Virgin and the Child (left) and a portrait of Christ above the mantel of the fireplace. Unless one regards Tip's monocle as having symbolic value, the picture is without the kinds of embedded emblems that characterize his earlier work. While Phiz has sufficiently distinguished each of the nine male travelers, the three young women might all be sisters, as the illustrator's eye for feminine beauty tended to run towards this particular type of thin brunette. Nevertheless, through giving her a tentative, timid quality Phiz leaves us in doubt as to which young woman is Little Dorrit, and which the proud, self-centered Fanny. A typical Browne elaboration of upon the text is Minnie Gowan's fruitlessly attempting to engage her husband in conversation, implying that, although not long married, the couple are already growing apart.

Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help.

Although the Phiz illustrations in Little Dorrit are often superfluous because of the descriptive power of the prose, Phiz's realization of William Dorrit's continuing arrogance and self-importance marks a significant moment in the novel as this is the first illustration in the second book, "Riches." Wealth, as Phiz points out, has done nothing to improve either William or his daughter Fanny; their sudden wealth has merely served to magnify their petulance. Only Amy remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the Dorrits to undertake the Grand Tour, complete with couriers and trains of pack-mules. On the other hand, Mahoney's illustration underscores Blandois' conception of himself as a cunning wolf stalking the English "sheep" he intends to fleece, reintroducing the criminal mastermind in the narrative pictorial sequence. The illustration is situated after the initial description of the alpine situation, just as the travellers are about to arrive at the convent for dinner.

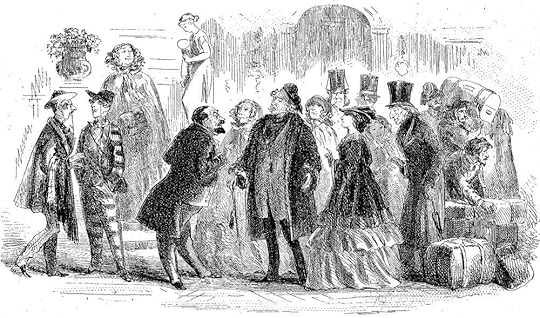

As he kissed her hand, with his best manner and his daintiest smile, the young lady drew a little nearer to her father

Chapter 1, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

"To the health of your distinguished family — of the fair ladies, your daughters!"

"Sir, I thank you again, I wish you good night. My dear, are our — ha — our people in attendance?"

"They are close by, father."

"Permit me!" said the traveller, rising and holding the door open, as the gentleman crossed the room towards it with his arm drawn through his daughter’s. "Good repose! To the pleasure of seeing you once more! To to-morrow!"

"As he kissed his hand, with his best manner and his daintiest smile, the young lady drew a little nearer to her father, and passed him with a dread of touching him.

"Humph!" said the insinuating traveller, whose manner shrunk, and whose voice dropped when he was left alone. "If they all go to bed, why I must go. They are in a devil of a hurry. One would think the night would be long enough, in this freezing silence and solitude, if one went to bed two hours hence.’

"Throwing back his head in emptying his glass, he cast his eyes upon the travellers' book, which lay on the piano, open, with pens and ink beside it, as if the night's names had been registered when he was absent. Taking it in his hand, he read these entries.

William Dorrit, Esquire / And suite. From France to Italy

Frederick Dorrit, Esquire

Edward Dorrit, Esquire

Miss Dorrit

Amy Dorrit

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan. From France to Italy.

Commentary:

The Dorrits, now having undergone a sea-change as a result of Pancks' investigations, are now wealthy enough to undertake the nineteenth-century equivalent of the eighteenth-century Grand Tour for young English aristocrats. Charles Dickens himself travelled through France and into Italy in 1844, and subsequently experienced the crossing of the St. Barnard Pass in the Alps from Switzerland into Italy. At a monastery in the Alps, the Dorrit party meets the honeymooning Gowans, as well as the rakish and insinuating Frenchman, Monsieur Blandois (the alias of Rigaud, the wife-murderer), all on their way to Rome. Amy, finding that Blandois' peculiar attentions make her feel uncomfortable, turns to her here-to-fore ineffectual father for protection. Mahoney's treatment of the foreign villain throughout the 1873 Household Edition volume is consistent with Rigaud's malignant appearance in other 19th-century programs of illustration: here we see the same Satanic smirk, the same curling moustache, the same exaggerated nose and Gallic chin (all that are visible of his face in the Mahoney illustration) that one sees in Sol Eytinge, Junior's Rigaud and Cavalletto (1867). In this illustration, Amy, dressed fashionably in a white gown and shawl (a departure from her previous, dark clothing) shrinks from the gesticulating Frenchman, whom he father regards with cold aloofness.

A relatively minor character in the original serial program who makes just four appearances (discounting his indistinct image in The Birds in the Cage (December 1855) — significantly at this point in the narrative to the extreme left, studying the English tourists in Phiz's The Travellers (Book 2, Chapter 1) — the scoundrel Rigaud, usually smoking, is very much a continuing character in Mahoney's program, introduced in the initial illustration in the Marseilles prison. In fact, in the fifty-eight illustrations, Rigaud appears thirteen times, eight of these being in Book the Second. Mahoney may, however, be overstating his importance to the plot, just as Harry Furniss has unreasonably minimized him in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition by showing him just once.

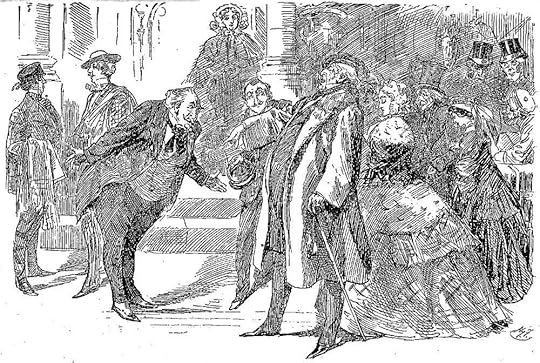

The Family Dignity is Affronted

Chapter 3, Book 2

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

So jealous was [William Dorrit] of [Miss Fanny's] being respected, that, on this very journey down from the Great Saint Bernard, he took sudden and violent umbrage at the footman's being remiss to hold her stirrup, though standing near when she dismounted; and unspeakably astonished the whole retinue by charging at him on a hard-headed mule, riding him into a corner, and threatening to trample him to death.

They were a goodly company, and the Innkeepers all but worshipped them. Wherever they went, their importance preceded them in the person of the courier riding before, to see that the rooms of state were ready. He was the herald of the family procession. The great travelling-carriage came next: containing, inside, Mr. Dorrit, Miss Dorrit, Miss Amy Dorrit, and Mrs. General; outside, some of the retainers, and (in fine weather) Edward Dorrit, Esquire, for whom the box was reserved. Then came the chariot containing Frederick Dorrit, Esquire, and an empty place occupied by Edward Dorrit, Esquire, in wet weather. Then came the fourgon with the rest of the retainers, the heavy baggage, and as much as it could carry of the mud and dust which the other vehicles left behind.

. . . . Nothing could exceed Mr Dorrit's indignation, as he turned at the foot of the staircase on hearing these apologies. He felt that the family dignity was struck at by an assassin's hand. He had a sense of his dignity, which was of the most exquisite nature. He could detect a design upon it when nobody else had any perception of the fact. His life was made an agony by the number of fine scalpels that he felt to be incessantly engaged in dissecting his dignity.

"Is it possible, sir," said Mr. Dorrit, reddening excessively, "that you have — ha — had the audacity to place one of my rooms at the disposition of any other person?" — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 3.

Commentary:

William Dorrit is put out by the innkeeper's giving the wealthy banker's wife, Mrs. Merdle, and her foppish son, Edmund Sparker, preferential treatment at the Great Saint Barnard crossing of the Alps into Italy. His grievance with the partiality shown to the other English travelers is exacerbated by Mrs. Merdle's cutting him socially, after his family's having been made much of by previous publicans on their route from France into Italy. "The great travelling-carriage" of the Dorrits here is reminiscent of that cumbersome vehicle in which Charles Dickens transported his family from London to Genoa in 1844. The Phiz illustration, unlike the parallel Mahoney illustration in the Household Edition, does not attempt to convey the majestic Alpine scenery. Perhaps Dickens expressly vetoed any such picturesque effect:

Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help.

Although, as Valerie Browne Lester points out, the Phiz illustrations in Little Dorrit are often superfluous because of the descriptive power of the prose, Phiz's realization of William Dorrit's continuing arrogance and self-importance marks a significant moment in the novel as this is the first illustration in the second book, "Riches." Wealth, as Phiz points out, has done nothing to improve either William or his daughter Fanny; their sudden wealth has merely served to magnify their petulance. Only Amy remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the Dorrits to undertake the Grand Tour, complete with couriers and trains of pack-mules. On the other hand, Mahoney's illustration underscores Blandois' conception of himself as a cunning wolf stalking the English "sheep" he intends to fleece, reintroducing the criminal mastermind in the narrative pictorial sequence.

In Part 11 (October 1856) Dickens reintroduces Rigaud, the murderer of his wife from the opening number in the prison cell at Marseilles, watching the English travelers make their descent into Italy from the convent at the Great Saint Barnard. Amy, noting his careful observation of the travelers' progress, feels quite uncomfortable. At the inn at Martigny (the capital of the French-speaking district in the canton of Valais in Switzerland), William Dorrit is mightily offended because the management has given away the suite he had reserved and has assigned it to Mrs. Merdle, a middle-aged aristocrat who has married a financier. Although Mrs. Merdle refuses to acknowledge her fellow travelers (because, of course, she knows of their less-than-aristocratic origins, despite their recently having inherited a fortune), as her carriage pulls away from the hotel, her son by her first marriage, Edmund Sparkler, peers at Amy and Fanny from the back window.

Mr. Dorrit and the Swiss Innkeeper

Chapter 3, Book 2

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

These equipages adorned the yard of the hotel at Martigny, on the return of the family from their mountain excursion. Other vehicles were there, much company being on the road, from the patched Italian Vettura — like the body of a swing from an English fair put upon a wooden tray on wheels, and having another wooden tray without wheels put atop of it — to the trim English carriage. But there was another adornment of the hotel which Mr. Dorrit had not bargained for. Two strange travellers embellished one of his rooms.

The Innkeeper, hat in hand in the yard, swore to the courier that he was blighted, that he was desolated, that he was profoundly afflicted, that he was the most miserable and unfortunate of beasts, that he had the head of a wooden pig. He ought never to have made the concession, he said, but the very genteel lady had so passionately prayed him for the accommodation of that room to dine in, only for a little half-hour, that he had been vanquished. The little half-hour was expired, the lady and gentleman were taking their little dessert and half-cup of coffee, the note was paid, the horses were ordered, they would depart immediately; but, owing to an unhappy destiny and the curse of Heaven, they were not yet gone.

Nothing could exceed Mr Dorrit's indignation, as he turned at the foot of the staircase on hearing these apologies. He felt that the family dignity was struck at by an assassin's hand. He had a sense of his dignity, which was of the most exquisite nature. He could detect a design upon it when nobody else had any perception of the fact. His life was made an agony by the number of fine scalpels that he felt to be incessantly engaged in dissecting his dignity.

"Is it possible, sir," said Mr. Dorrit, reddening excessively, "that you have — ha — had the audacity to place one of my rooms at the disposition of any other person?"

Thousands of pardons! It was the host's profound misfortune to have been overcome by that too genteel lady. He besought Monseigneur not to enrage himself. He threw himself on Monseigneur for clemency. If Monseigneur would have the distinguished goodness to occupy the other salon especially reserved for him, for but five minutes, all would go well.

"No, sir," said Mr. Dorrit. "I will not occupy any salon. I will leave your house without eating or drinking, or setting foot in it.

"How do you dare to act like this? Who am I that you — ha — separate me from other gentlemen?"

Commentary:

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's interpretation of the haughty behaviour of William Dorrit emphasizes his sheer bulk. Amy's father, having inherited the wealth to support his conception of himself as a "gentleman," seems to regard himself as an aristocrat superior even to Captain Sparkler's widow, the wife of the English banker Merdle. She, likewise, has an exaggerated sense of her own importance because her husband's wealth she feels, entitles her to pre-empt the Dorrits' reservation at the Alpine inn. She has probably appropriated the Dorrits' rooms by lavishly tipping the groveling Swiss landlord.

William Dorrit is understandably put out by the innkeeper's giving the banker's wife and her foppish son, Edmund Sparker, preferential treatment at the Great Saint Barnard crossing of the Alps into Italy. His grievance with the partiality shown to the other English travelers is exacerbated by Mrs. Merdle's cutting him socially, after his family's having been made much of by previous publicans on their route from France into Italy. The Dorrits' "great travelling-carriage" (not depicted by Furniss or any of the other illustrators) is reminiscent of that cumbersome vehicle in which Charles Dickens transported his family from London to Genoa in 1844.

Only Amy (squeezed in between Fanny and her uncle in the Furniss version) remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the formerly indigent Dorrits to undertake an upper-middle-class version of the eighteenth-century the Grand Tour, complete with couriers, servants (suggested by the figures in top-hats in the Furniss illustration), and trains of pack-mules. The corpulent innkeeper bows low before the incensed English traveler with the fur collar and walking stick, obvious manifestations of his "gentlemanly" pretentions, an imperious and portly figure whose gesture is suggestive of contempt for those who have usurped his prerogative and occupied the rooms reserved for his suite. Similarly, James Mahoney's parallel illustration in the Household Edition underscores the silent aloofness of Amy's father as she clings to him for support while Blandois ogles her.

Always standing on one jutting point looking down after them.

Chapter 3, Book 2

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Mr. Gowan stood aloof with his cigar and pencil, but Mr. Blandois was on the spot to pay his respects to the ladies. When he gallantly pulled off his slouched hat to Little Dorrit, she thought he had even a more sinister look, standing swart and cloaked in the snow, than he had in the fire-light over-night. But, as both her father and her sister received his homage with some favour, she refrained from expressing any distrust of him, lest it should prove to be a new blemish derived from her prison birth.

Nevertheless, as they wound down the rugged way while the convent was yet in sight, she more than once looked round, and descried Mr. Blandois, backed by the convent smoke which rose straight and high from the chimneys in a golden film, always standing on one jutting point looking down after them. Long after he was a mere black stick in the snow, she felt as though she could yet see that smile of his, that high nose, and those eyes that were too near it. And even after that, when the convent was gone and some light morning clouds veiled the pass below it, the ghastly skeleton arms by the wayside seemed to be all pointing up at him.

Commentary:

James Mahoney's treatment of the foreign villain in the 1873 Household Edition volume is consistent with Rigaud's/Blandois's malignant appearance in other 19th-century programs of illustration: here we see the same Satanic smirk, the same curling moustache, the same exaggerated nose and Gallic chin (all that are visible of his face in the Mahoney illustration) that one sees in Sol Eytinge, Junior's Rigaud and Cavalletto (1867). The pose of the evil genius watching his prey, however, is rather overstated, and is perhaps even a red herring. Mahoney conveys well the majesty of the Alpine backdrop, juxtaposing the dark figure of the sinister observer against the white peaks which the rising sun catches and ruled lines of the valleys still dark after the breakfast scene at the inn. The crosses represent the nearby convent, and a few mules and muleteers imply the presence of a vast train, off left. A relatively minor character in the original serial program who makes just four appearances — the scoundrel is very much a continuing character in Mahoney's program, introduced in the initial illustration in the Marseilles prison. In fact, in the fifty-eight illustrations, Rigaud/Blandois appears thirteen times, eight of these being in Book the Second. Mahoney may, however, be overstating his importance to the plot, just as Harry Furniss has unreasonably minimized him in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition by showing him just once.

The gentlemanly murderer of his wife, Rigaurd (alias Blandois) attaches himself to the Gowans when they are honeymooning in Italy, probably with the intention of defrauding them and the other travelling English family, the Dorrits. In his own mind, he is a cosmopolitan lady-killer with exaggerated courtly French manners; Phiz and later illustrators imbue him with more than a whiff of Satanic sulfur, emphasized in his smoking cigarettes, and in the Mahoney illustration set in the Alps by his proximity to the smoke from the nearby convent.

Kim wrote: "

Tip"

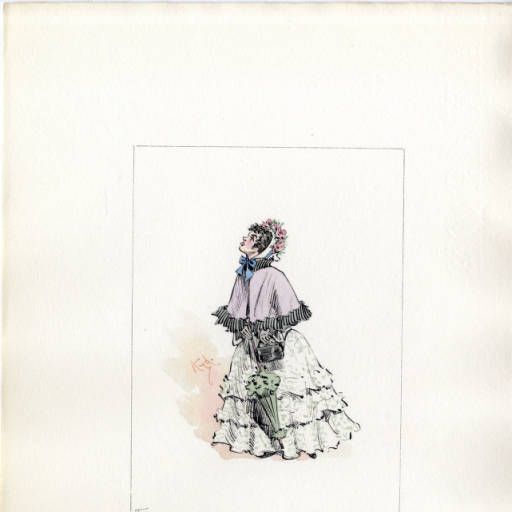

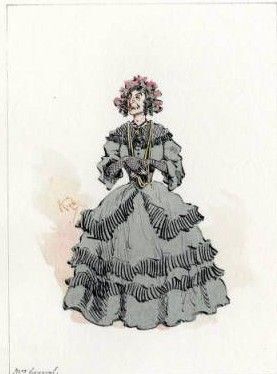

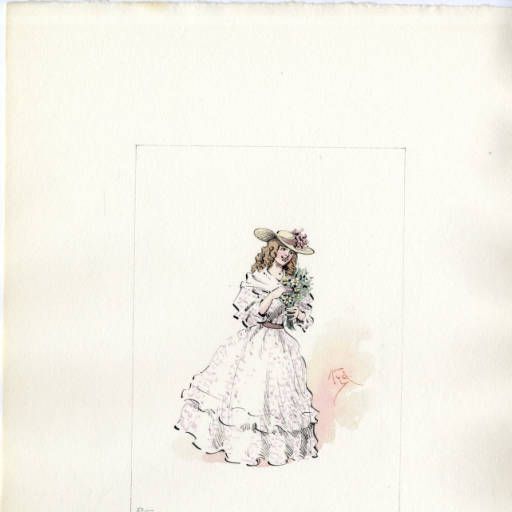

As always, thanks for the illustrations Kim. You have given us five Kyd illustrations. What to say? Well, let me put this out to all the other Curiosities. Of the five, I think the one of Pet is the best.

Any other opinions?

Tip"

As always, thanks for the illustrations Kim. You have given us five Kyd illustrations. What to say? Well, let me put this out to all the other Curiosities. Of the five, I think the one of Pet is the best.

Any other opinions?

Tristram wrote: "The narrator has a fine psychological eye with regard to upstart sensibilities:

Tristram wrote: "The narrator has a fine psychological eye with regard to upstart sensibilities:”He felt that the family dignity was struck at by an assassin's hand. He had a sense of his dignity, which was of the most exquisite nature. He could detect a design upon it when nobody else had any perception of the fact. His life was made an agony by the number of fine scalpels that he felt to be incessantly engaged in dissecting his dignity.”."

What a striking image! And sad.

I enjoyed the symmetry of the two parts of the book starting out with a group of travelers, and probably because I was a little lazy and reading fast and could not remember which character says hem, hem in the middle of every sentence, it took me a bit too long to figure out we were looking at the Dorrits, and it was fun for me seeing that fall into place once it finally did. Kind of Dickens to provide us slow people with a character index at the end of the chapter!

Mary Lou wrote: "This was an offhand remark, but struck me as being rather ominous. Has the memory of Arthur come between Pet and Gowan (and does he call her Pet or Minnie, I wonder)?"

Mary Lou wrote: "This was an offhand remark, but struck me as being rather ominous. Has the memory of Arthur come between Pet and Gowan (and does he call her Pet or Minnie, I wonder)?"I can't imagine him calling her either. Probably he calls her Mrs. Gowan.

I thought it was funny how he comments on how useful the St. Bernard dogs are for monastery fundraising, after using his own dog to advance his courtship of MinniePet.

Peacejanz wrote: "Aw, come on - you never heard a silly woman play like a child to her intended -- You sweet thing, beg me, tell me how wonderful I am. Or I will tell you how wonderful you are. d And you can bring g..."

I usually fell in with a different kind of woman when I was in my days of falling in and out. It was normally the kind of woman who regarded conversation as a delightful exercise in fencing, who had a lot of repartee and was always willing and able to stand her ground. And they were blonde, more often than not ;-) Before I and my children made my wife's hair go grey, she was a blonde, too ... but she never ever gave me the helpless child act. But then, men are different, and I am definitely not like Arthur.

I usually fell in with a different kind of woman when I was in my days of falling in and out. It was normally the kind of woman who regarded conversation as a delightful exercise in fencing, who had a lot of repartee and was always willing and able to stand her ground. And they were blonde, more often than not ;-) Before I and my children made my wife's hair go grey, she was a blonde, too ... but she never ever gave me the helpless child act. But then, men are different, and I am definitely not like Arthur.

Jantine wrote: "Also I love how the Dorrits are dislikeable as ever. They behave exactly in a way that they would fit into the mold of those Karen-memes. People like this are of all times and places, and I like ho..."

I agree: The Dorrits bear testimony to Dickens's growing skills in characterization and in creating psychologically believable characters. As Peter said some weeks ago, in Little Dorrit we are a long way further than in Pickwick Papers or Nicholas Nickleby. Not only has the exuberant optimism gopne but the characters have deepened.

I agree: The Dorrits bear testimony to Dickens's growing skills in characterization and in creating psychologically believable characters. As Peter said some weeks ago, in Little Dorrit we are a long way further than in Pickwick Papers or Nicholas Nickleby. Not only has the exuberant optimism gopne but the characters have deepened.

Jantine wrote: "Not only has the exuberant optimism gone but the characters have deepened...."

Jantine wrote: "Not only has the exuberant optimism gone but the characters have deepened...."I miss the exuberant optimism. Thank God for Mr. F's aunt and Flora, or there wouldn't be any light-hearted relief in this book, and even Flora is tinged with longing and sadness.

Mary Lou wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Not only has the exuberant optimism gone but the characters have deepened...."

I miss the exuberant optimism. Thank God for Mr. F's aunt and Flora, or there wouldn't be any light-h..."

Yes. I find this book to be very sad, much sadder than even Bleak House. There are, no doubt, many reasons and speculations why an overall shift in tone might occur. That said, I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” Perhaps as one ages there is more ease in being ironic, sarcastic and gloomy than being joyous. Does experience with life and its trials make us less joyous and unfettered?

I miss the exuberant optimism. Thank God for Mr. F's aunt and Flora, or there wouldn't be any light-h..."

Yes. I find this book to be very sad, much sadder than even Bleak House. There are, no doubt, many reasons and speculations why an overall shift in tone might occur. That said, I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” Perhaps as one ages there is more ease in being ironic, sarcastic and gloomy than being joyous. Does experience with life and its trials make us less joyous and unfettered?

Peter wrote: "I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” ..."

Peter wrote: "I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” ..."Dang, Peter, that's depressing! Mostly because I think you're exactly right. A good reminder that, especially as we age, we must look for joy and humor wherever we can find it.

I'm really enjoying the book, although I'm finding it a bit frustrating that the unpleasant characters like the Dorrits, Mrs Clennam, and Rigaud are the interesting ones, and the good characters like Amy, Arthur, Daniel and Frederick are a bit flat.

I'm really enjoying the book, although I'm finding it a bit frustrating that the unpleasant characters like the Dorrits, Mrs Clennam, and Rigaud are the interesting ones, and the good characters like Amy, Arthur, Daniel and Frederick are a bit flat.I do like the Merdles though, and the characters such as Society that revolve around them. I think they have a fascinating dynamic.

I'm really stuck on one small point though - when Amy concludes her letter by referring to "I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him." I'm not really sure who she's referring to. Is it her father ?

I'm not smart enough for these subtleties I'm afraid...

I have found the isolation that Amy feels now that the family has come into wealth and position interesting though. The way she is pining for her old simpler ways, feeling lonely and doesn't feel anything in common with her "new" family reminds me of Princess Diana.

I have found the isolation that Amy feels now that the family has come into wealth and position interesting though. The way she is pining for her old simpler ways, feeling lonely and doesn't feel anything in common with her "new" family reminds me of Princess Diana. Both could have been expected to suddenly have everything they wished for, but often what we think we wanted (particularly if it is for someone else) doesn't turn out the way we expect. Lottery wins don't always solve our problems.

Peter wrote: "Yes. I find this book to be very sad, much sadder than even Bleak House."

I agree.

At least in Bleak House most people had a place they could go to, people who cared for them. Even Jo had Nemo and later George and the angry farmer. Ada and Richard would at any moment be welcome at Bleak House. Lady Dedlock had her marriage with a man who dearly loved her, even if he was pompous and I'm still not sure if she loved him. Etc. Etc.

Meanwhile, in Little Dorrit everyone is lonely. Not just lonely because they do not notice the connection or home they could have, but lonely because the connections they have are taken away, and are not replaced. Because where Richard's greed was fuelled by wanting to do the right thing for Ada and their child, the Dorrits' pride does not even really pretend to be for anyone but themselves.

I agree.

At least in Bleak House most people had a place they could go to, people who cared for them. Even Jo had Nemo and later George and the angry farmer. Ada and Richard would at any moment be welcome at Bleak House. Lady Dedlock had her marriage with a man who dearly loved her, even if he was pompous and I'm still not sure if she loved him. Etc. Etc.

Meanwhile, in Little Dorrit everyone is lonely. Not just lonely because they do not notice the connection or home they could have, but lonely because the connections they have are taken away, and are not replaced. Because where Richard's greed was fuelled by wanting to do the right thing for Ada and their child, the Dorrits' pride does not even really pretend to be for anyone but themselves.

David wrote: ""I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him." I'm not really sure who she's referring to. Is it her father ?"

David wrote: ""I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him." I'm not really sure who she's referring to. Is it her father ?"I think it is, mostly because he tends to be the main target of her attentions, and also in the same paragraph she talks about him now having a distance from her, not the same as before, and places him in a disapproving triumvirate with Fanny and Mrs. General.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” ..."Dang, Peter, that's depressing! Mostly because I think you're exactly right. A go..."

I don't know--I find as I get older that books I thought were very serious when I read them in my 20s are actually quite funny. To the Lighthouse, for instance. The more I become like the father in the book, the more sympathetically ridiculous he seems to me.

Granted that is a reading experience, not a writing experience. But if some writers grow more serious as they age, others may grow less convinced by their own melodrama, and lighter in tone.

Over the process of reading all these books, I'm beginning to think Great Expectations is my favorite Dickens (one of his last), and while that has its own melodrama it also has a narrator who is possibly gaining a sense of proportion as the book develops.

David wrote: "I'm finding it a bit frustrating that the unpleasant characters like the Dorrits, Mrs Clennam, and Rigaud are the interesting ones, and the good characters like Amy, Arthur, Daniel and Frederick are a bit flat...."

David wrote: "I'm finding it a bit frustrating that the unpleasant characters like the Dorrits, Mrs Clennam, and Rigaud are the interesting ones, and the good characters like Amy, Arthur, Daniel and Frederick are a bit flat...."Sadly, this is often the case with Dickens. His villains, sidekicks, and supporting cast are all masterful, but his heroes can be rather insipid.

David wrote: I'm not really sure who she's referring to. Is it her father ?...

I had to go back and read the passage again to be sure, but, yes -- I interpreted that as being about Mr. Dorrit. Odd, though, that she purposely didn't name him. Why?

David wrote: "Lottery wins don't always solve our problems..."

No, money doesn't always buy happiness, does it? There's a show here in the States called "My Lottery Dream Home" or something to that effect. It shows, as you'd guess, lottery winners buying new homes. They aren't always multi-million $$ winners, and some of the houses are rather modest. But some others are palatial. I always wonder if they've taken into account the cost of furnishing, cleaning, upkeep, property taxes, etc. It would be fascinating to me to have them follow up with these people a five years later to see how they're living. I'm sure Dickens won't rob of us the opportunity to see how their sudden wealth will impact the Dorrits.

While I understand Amy's feeling of loss, etc. my 21st century self is annoyed that she doesn't just thumb her nose at her family and go back to slumming it in London if she really feels that way. Even if they disowned her, certainly her newly-respectable name would open a few doors for her, or she could go to work for the Plornishes, Flora, Doyce and Clennam, or even just go back to sewing for Mrs. Clennam if she really feels the need to humble herself. But she can't leave poor daddy. I swear, I used to like Amy, but she's more and more like Little Nell with every chapter.

Peter wrote: "Of the five, I think the one of Pet is the best.

Peter wrote: "Of the five, I think the one of Pet is the best.Any other opinions? ..."

Pet looks as if she should be on a swing hung from flowering vines. But, yes - it's the most pleasant of the bunch.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Swi...

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "Of the five, I think the one of Pet is the best.

Any other opinions? ..."

Pet looks as if she should be on a swing hung from flowering vines. But, yes - it's the most pleasant of the..."

Perfect. No Kyding.

Any other opinions? ..."

Pet looks as if she should be on a swing hung from flowering vines. But, yes - it's the most pleasant of the..."

Perfect. No Kyding.

I agree and I don't agree. As I age, and no longer have the worry/concern of a job with asses, I am more joyful and peaceful. I think my personal writing is kinder, more informative than before. And Amy is getting downright dull. I liked her from the beginning -- but I skip over her dullness now. No guts, no glory. Thank goodness we still have Arthur who is dull, too. Maybe as we learn more about life we become more negative - certainly as Dickens got older, he had more troubles but don't we all? peace, janz

I agree and I don't agree. As I age, and no longer have the worry/concern of a job with asses, I am more joyful and peaceful. I think my personal writing is kinder, more informative than before. And Amy is getting downright dull. I liked her from the beginning -- but I skip over her dullness now. No guts, no glory. Thank goodness we still have Arthur who is dull, too. Maybe as we learn more about life we become more negative - certainly as Dickens got older, he had more troubles but don't we all? peace, janz

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

Tip"

As always, thanks for the illustrations Kim. You have given us five Kyd illustrations. What to say? Well, let me put this out to all the other Curiosities. Of the five, I think ..."

Kyd has got it all wrong if you ask me: Little Dorrit looks like a younger version of Mrs Gamp, and Mrs General looks like Mrs Todgers. I picture Mrs General as a much more spacious woman, with a large bosom for her feelings of propriety and importance to rankle in.

Tip"

As always, thanks for the illustrations Kim. You have given us five Kyd illustrations. What to say? Well, let me put this out to all the other Curiosities. Of the five, I think ..."

Kyd has got it all wrong if you ask me: Little Dorrit looks like a younger version of Mrs Gamp, and Mrs General looks like Mrs Todgers. I picture Mrs General as a much more spacious woman, with a large bosom for her feelings of propriety and importance to rankle in.

Julie wrote: "I thought it was funny how he comments on how useful the St. Bernard dogs are for monastery fundraising, after using his own dog to advance his courtship of MinniePet."

That's a striking detail I didn't think of. It might also account for why Arthur took so much umbrage at the harmless dog.

That's a striking detail I didn't think of. It might also account for why Arthur took so much umbrage at the harmless dog.

Peter wrote: "Perhaps as one ages there is more ease in being ironic, sarcastic and gloomy than being joyous."

This is probably true, even though my personal form of humour has always been irony and sarkasm.

This is probably true, even though my personal form of humour has always been irony and sarkasm.

David wrote: "I'm really stuck on one small point though - when Amy concludes her letter by referring to "I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him." I'm not really sure who she's referring to. Is it her father ?"

I am pretty sure that Amy is referring to her father here. Her entire life is focussed on the old man's well-being, and she is probably the only one to see that his new position has brought him into the dilemma of fearing some exposure to shame by people who know of his past. One might say that Mr Dorrit should be a little bit more self-confident but after a life in prison, he is probably more insecure than he was in the first place, and one must take into account that Society was (and is) prejudiced and that most people the Dorrits deal with now would start looking down on them if the truth were known. The scalpels are at works here.

Another thing may be that Amy misses the good old days when she was important to her father. Now he does not need here any more, and her pining for the past is an additional source of insecurity and potential embarrassment for the family.

I am pretty sure that Amy is referring to her father here. Her entire life is focussed on the old man's well-being, and she is probably the only one to see that his new position has brought him into the dilemma of fearing some exposure to shame by people who know of his past. One might say that Mr Dorrit should be a little bit more self-confident but after a life in prison, he is probably more insecure than he was in the first place, and one must take into account that Society was (and is) prejudiced and that most people the Dorrits deal with now would start looking down on them if the truth were known. The scalpels are at works here.

Another thing may be that Amy misses the good old days when she was important to her father. Now he does not need here any more, and her pining for the past is an additional source of insecurity and potential embarrassment for the family.

Julie wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "I often wonder if it is actually more difficult to write humour, to be exuberant as one “ages.” ..."

Dang, Peter, that's depressing! Mostly because I think you're ex..."

Hi Julie