The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit Part One Chapters 5-8

Chapter 6

The Father of the Marshalsea

“That a child would be born to you in a place like this? … What does it signify?” the doctor of the Marshalsea

If there was any doubt that prisons and different ways of being imprisoned would form the foundation of this novel, this chapter should dispel that idea.

To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and his siblings all spent time in that prison. Charles, who was 12 at the time, went to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. Most of the young Charles’s wages bought food for his family in jail and Charles was very familiar with the jail, its inmates, and its routines. At the time Little Dorrit was being written the Marshalsea had been closed. When we read the last sentence of the first paragraph “it is gone now, and the world is none the worse without it” we know those words come from both Dickens’s own experience and his heart.

The first paragraphs of this chapter establish the general condition of the jail, introduce us to its inhabitants, and zeros in on the character of William Dorrit, Little Dorrit’s father. One might suspect that the description of the jail, the jailers, and the criminals would be rather depressing and grim after reading Chapter One of this novel but such is not the case. Rather, Dickens creates a setting with character interactions which are humourous and witty. We learn that Mr Dorrit has a very timid and pregnant wife, and two children, one a boy who is three years old and one a girl who is two. The jailor tells Mr Dorrit that he wonders who is the most helpless person in the family, Dorrit himself or the unborn child. The jailor also predicts that Mr Dorrit will never get out of jail “unless his creditors take him by the shoulders and shove him out.”

Dickens recounts the birth of Little Dorrit as a community event. The men of the jail all go hide but the women, lead by a Mrs Bangham, a chairwoman, messenger, and former resident of the Marshalsea, rally round to assist in the birth. Mrs Bangham cannot recall the last time there was a birth in the jail. The doctor in attendance, whose name is Haggage, attends the birth and happily administers brandy to both Mrs Dorrit and himself. The birth completed, and a very little baby girl admitted into the world. The doctor, who is fully medicated with brandy, extols the advantages of being in jail by declaring “It's freedom sir, it's freedom.” An interesting twist of the function of a jail.

Time passes, and Mr Dorrit becomes the longest inhabitant of the jail. With this, he becomes more and more recognized as a unique person. Eight years after Little Dorrit’s birth, his wife, on a visit an old friend, dies. Here we need a bit of an explanation. Mr Dorrit was the member of the family who was convicted. The other members of his family were not considered criminals, but since the “breadwinner” of the family was in jail, they went too. They had freedom of movement to the “outside” world. It's a bit difficult to imagine in today’s world isn’t it? It does, however, explain why Little Dorrit was free to come and go within the prescribed hours the jail was “open” to the public.

More time passes and Mr Dorrit becomes known as the Father of the Marshalsea and we are told “he grew to be proud of the title.” As the “Father,” newly convicted prisoners were presented to him, and there was an expectation that each new resident of the jail would pay some financial homage to Mr Dorrit.

Thoughts

We have read how horrid and unpleasant the jail was in Marseilles in Chapter One. In this chapter the Marshalsea is, by comparison, rather comfortable, and presented with a much lighter and humourous tone. Dickens has thus presented the experience of being incarcerated through different lenses. What reasons do you think Dickens has presented these two jails in such a different light?

There is a convivial mood in the Marshalsea prison. What might be the reason for Dickens creating this tone?

As a side note, do you wonder, as I have, why Mr Dorrit would not use the monetary gifts he receives as payments to get out of jail? Is it as simple as he is attempting to guarantee the comforts of his family and has, as a consequence, no money is left over? Is there a darker purpose Dickens may be suggesting?

What is your first impression of Mr Dorrit, the Father of the Marshalsea?

The Father of the Marshalsea

“That a child would be born to you in a place like this? … What does it signify?” the doctor of the Marshalsea

If there was any doubt that prisons and different ways of being imprisoned would form the foundation of this novel, this chapter should dispel that idea.

To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and his siblings all spent time in that prison. Charles, who was 12 at the time, went to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. Most of the young Charles’s wages bought food for his family in jail and Charles was very familiar with the jail, its inmates, and its routines. At the time Little Dorrit was being written the Marshalsea had been closed. When we read the last sentence of the first paragraph “it is gone now, and the world is none the worse without it” we know those words come from both Dickens’s own experience and his heart.

The first paragraphs of this chapter establish the general condition of the jail, introduce us to its inhabitants, and zeros in on the character of William Dorrit, Little Dorrit’s father. One might suspect that the description of the jail, the jailers, and the criminals would be rather depressing and grim after reading Chapter One of this novel but such is not the case. Rather, Dickens creates a setting with character interactions which are humourous and witty. We learn that Mr Dorrit has a very timid and pregnant wife, and two children, one a boy who is three years old and one a girl who is two. The jailor tells Mr Dorrit that he wonders who is the most helpless person in the family, Dorrit himself or the unborn child. The jailor also predicts that Mr Dorrit will never get out of jail “unless his creditors take him by the shoulders and shove him out.”

Dickens recounts the birth of Little Dorrit as a community event. The men of the jail all go hide but the women, lead by a Mrs Bangham, a chairwoman, messenger, and former resident of the Marshalsea, rally round to assist in the birth. Mrs Bangham cannot recall the last time there was a birth in the jail. The doctor in attendance, whose name is Haggage, attends the birth and happily administers brandy to both Mrs Dorrit and himself. The birth completed, and a very little baby girl admitted into the world. The doctor, who is fully medicated with brandy, extols the advantages of being in jail by declaring “It's freedom sir, it's freedom.” An interesting twist of the function of a jail.

Time passes, and Mr Dorrit becomes the longest inhabitant of the jail. With this, he becomes more and more recognized as a unique person. Eight years after Little Dorrit’s birth, his wife, on a visit an old friend, dies. Here we need a bit of an explanation. Mr Dorrit was the member of the family who was convicted. The other members of his family were not considered criminals, but since the “breadwinner” of the family was in jail, they went too. They had freedom of movement to the “outside” world. It's a bit difficult to imagine in today’s world isn’t it? It does, however, explain why Little Dorrit was free to come and go within the prescribed hours the jail was “open” to the public.

More time passes and Mr Dorrit becomes known as the Father of the Marshalsea and we are told “he grew to be proud of the title.” As the “Father,” newly convicted prisoners were presented to him, and there was an expectation that each new resident of the jail would pay some financial homage to Mr Dorrit.

Thoughts

We have read how horrid and unpleasant the jail was in Marseilles in Chapter One. In this chapter the Marshalsea is, by comparison, rather comfortable, and presented with a much lighter and humourous tone. Dickens has thus presented the experience of being incarcerated through different lenses. What reasons do you think Dickens has presented these two jails in such a different light?

There is a convivial mood in the Marshalsea prison. What might be the reason for Dickens creating this tone?

As a side note, do you wonder, as I have, why Mr Dorrit would not use the monetary gifts he receives as payments to get out of jail? Is it as simple as he is attempting to guarantee the comforts of his family and has, as a consequence, no money is left over? Is there a darker purpose Dickens may be suggesting?

What is your first impression of Mr Dorrit, the Father of the Marshalsea?

Chapter 7

The Child of the Marshalsea

“At what period in her early life the little creature began to perceive that it was not the habit of all the world to live locked up in narrow yards surrounded by high walls with spikes at the top would be a difficult question to settle.”

Little Dorrit’s life in the Marshalsea was unusual to say the least. The turnkey became her godfather. Little Dorrit was given a chair by the turnkey and she spent hours with him at his post. It could be said that he was more of a father figure to her than her own father. In fact, it was the turnkey’s thought that he would make Little Dorrit the sole beneficiary of his will. His only concern was that Little Dorrit’s father or someone else would be able to get their hands on Little Dorrit’s inheritance. Alas, the turnkey died intestate. Thus, Little Dorrit’s first opportunity to have some independence in life was thwarted.

Due to her ineffectual father Little Dorrit assumes the role of the parent at the tender age of 13. Her father becomes her child, and his other children, Tip and Fanny, become her children as well. Her sister Fanny had a desire to dance and so Little Dorrit made an arrangement with an incarcerated dance instructor to help her “wayward” sister learn to dance. Little Dorrit’s “idle” brother Tip, through the kindness of the jailor, obtained a job outside the prison walls as well. Tip was indeed idle and went through numerous jobs - even more than Richard Carstone - until he became a scam artist, was arrested, and imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. As Tip says, “ I have come back in what I may call a new way. I am off the volunteer list all together. I am in now as one as one of the regulars.”

Little Dorrit did not forget her own needs. Through another prisoner, a seamstress, Little Dorrit learns to sew. At the age of 22 she is working “beyond the walls” as well. She does, however, keep her private life and her nightly residence to herself. Her life has thus become divided between the “free city” and “the iron gates.” Thus, Little Dorrit is leading two secret lives every day. To her father and siblings she is a little child who leaves the prison for the day but her destination is unknown. To her employer, she is a seamstress who leaves their private residence and returns home to a place not known. As Dickens states “This was the life, and this the history.” What Dickens also tells us at the end of this chapter is that “upon one dull September evening [Little Dorrit was] observed at a distance by Arthur Clennam.”

Thoughts

I’ve just noticed that I have not used Little Dorrit’s Christian name yet. Her first name is Amy. Sorry about that. That slip does, however, help remind us about earlier comments how a person’s name often acts as an aid to establish the character. For example, the name changes to Tattycoram and Pet in Chapter Two. When a person loses their name, has it changed, or chooses to change it themselves there are usually undercurrents of meaning that occur. We may see name changes in the coming weeks. We should pause and ask why.

Given the background we have learned about Amy in this chapter what is your initial response to her character?

We have discovered how a person can be in prisoner and feel imprisoned in numerous ways. With Little Dorrit we see a character who has multiple layers of secrets as well as being a person who lives in a jail. How might the variety of secrets that Amy has effect her character as we move through the novel?

Amy is the parent to both her father and her siblings. What significance for the novel might this hold?

Dickens makes it clear that Arthur Clennam has an interest in Little Dorrit. How might Dickens further develop this relationship in the novel?

The Child of the Marshalsea

“At what period in her early life the little creature began to perceive that it was not the habit of all the world to live locked up in narrow yards surrounded by high walls with spikes at the top would be a difficult question to settle.”

Little Dorrit’s life in the Marshalsea was unusual to say the least. The turnkey became her godfather. Little Dorrit was given a chair by the turnkey and she spent hours with him at his post. It could be said that he was more of a father figure to her than her own father. In fact, it was the turnkey’s thought that he would make Little Dorrit the sole beneficiary of his will. His only concern was that Little Dorrit’s father or someone else would be able to get their hands on Little Dorrit’s inheritance. Alas, the turnkey died intestate. Thus, Little Dorrit’s first opportunity to have some independence in life was thwarted.

Due to her ineffectual father Little Dorrit assumes the role of the parent at the tender age of 13. Her father becomes her child, and his other children, Tip and Fanny, become her children as well. Her sister Fanny had a desire to dance and so Little Dorrit made an arrangement with an incarcerated dance instructor to help her “wayward” sister learn to dance. Little Dorrit’s “idle” brother Tip, through the kindness of the jailor, obtained a job outside the prison walls as well. Tip was indeed idle and went through numerous jobs - even more than Richard Carstone - until he became a scam artist, was arrested, and imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. As Tip says, “ I have come back in what I may call a new way. I am off the volunteer list all together. I am in now as one as one of the regulars.”

Little Dorrit did not forget her own needs. Through another prisoner, a seamstress, Little Dorrit learns to sew. At the age of 22 she is working “beyond the walls” as well. She does, however, keep her private life and her nightly residence to herself. Her life has thus become divided between the “free city” and “the iron gates.” Thus, Little Dorrit is leading two secret lives every day. To her father and siblings she is a little child who leaves the prison for the day but her destination is unknown. To her employer, she is a seamstress who leaves their private residence and returns home to a place not known. As Dickens states “This was the life, and this the history.” What Dickens also tells us at the end of this chapter is that “upon one dull September evening [Little Dorrit was] observed at a distance by Arthur Clennam.”

Thoughts

I’ve just noticed that I have not used Little Dorrit’s Christian name yet. Her first name is Amy. Sorry about that. That slip does, however, help remind us about earlier comments how a person’s name often acts as an aid to establish the character. For example, the name changes to Tattycoram and Pet in Chapter Two. When a person loses their name, has it changed, or chooses to change it themselves there are usually undercurrents of meaning that occur. We may see name changes in the coming weeks. We should pause and ask why.

Given the background we have learned about Amy in this chapter what is your initial response to her character?

We have discovered how a person can be in prisoner and feel imprisoned in numerous ways. With Little Dorrit we see a character who has multiple layers of secrets as well as being a person who lives in a jail. How might the variety of secrets that Amy has effect her character as we move through the novel?

Amy is the parent to both her father and her siblings. What significance for the novel might this hold?

Dickens makes it clear that Arthur Clennam has an interest in Little Dorrit. How might Dickens further develop this relationship in the novel?

Chapter 8

The Lock

‘Anyone can go in’ replied the old man plainly; adding by the significance of his emphasis,’ but it is not everyone who can go out.”

OK. I admit it. When I see the above line from the chapter under discussion I think of The Eagles great song “Hotel California.” Does anyone else think this way? The Marshalsea Prison and Hotel California. Just wondering.

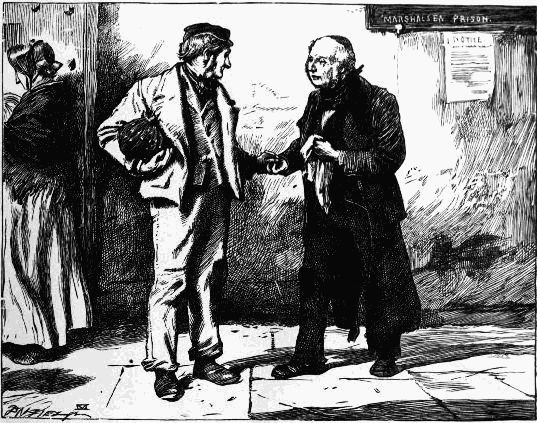

And now back to Dickens. The second paragraph of this chapter is a masterpiece of character description. Arthur approaches this shabbily dressed man and asks him what the place before them was. The answer is the Marshalsea prison. When Arthur asks the man if he knows the name Dorrit he discovers that the man he is talking to is Frederick Dorrit, and he is the brother to William Dorrit, Amy's father. Frederick tells Arthur that much of what happens outside the walls of the prison are never recounted to his brother William. Arthur is then conducted inside the prison and to William Dorrit’s cell. There, Arthur sees Little Dorrit preparing supper for her father. Arthur realizes that the food being presented to her father is the food Little Dorrit was given for herself at his mother’s home.

What follows is the ritual of a person being presented to Amy's father, William Dorrit assumes his role of the Father of the Marshalsea and then tells Arthur how seldom people come to the jail without being presented. Next, Arthur is told most people offer a testimonial to the father of the jail. Arthur complies.

A bell is heard ringing which signifies that the jail’s front door will be locked soon. Fanny and Tip enter the room and demand fresh clothes for themselves. Little Dorrit opens an old chest of drawers and hands bundles to her brother and sister. Clearly, Little Dorrit is performing the role of the parent to both her father and her siblings. The prison bells are heard ringing again. Before leaving, Arthur presents a testimonial to William Dorrit. Arthur then assures little Dorrit that he only followed her in order to “endeavour to render you and your family some service.”Arthur tells little Dorrit that he hopes to gain her confidence. In response, little Dorrit says “you are very good sir you speak very earnestly to me - but I wish you had not watched me.”

Thoughts

There is a formality that exists within the walls of the jail. There is also a clear hierarchy of persons and roles Within the jail. How would such an organized approach to an institution be of benefit to both those within the jail and those who visit it?

At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell … oops, I mean Little Dorrit.

Is Arthur simply a good man looking to do good deeds for others?

Is Arthur simply trying to learn more about his own family’s mystery and hopes that Little Dorrit can help him?

Could it be possible that Arthur has an emotional interest in little Dorrit?

What other motives may there be for Arthur’s interest in Little Dorrit?

What follows next in the chapter is Dickens developing more of the background of both Little Dorrit and Mrs. Clennam. We learn that Mrs. Clennam offered Little Dorrit a position within her household. Could it be possible that this is one way Mrs Clennam is trying to pay penance for some previous action or event in her life? In any case, Little Dorrit is concerned that the truth of her residence and background may someday be learned by Mrs. Clennam. More and more, we see Dickens weaving the idea of secrets being held by some and secrets being revealed or sought by others. In the middle of this vortex is Little Dorrit, Arthur, and Mrs Clennam.

The bell for the closing of the jail for the evening is heard again. Too late! The main gate has been locked and Arthur has become, for at least one night, also imprisoned in the Marshalsea. We discussed earlier how imprisonment is a trope in this novel. Here we find layers of mystery and imprisonment. Arthur is seeking the answers to his family’s mystery. For at least this night he is imprisoned in the Marshalsea. As Arthur passes the night in prison there are three images of people that run through his mind. The first is of his father who is dead but his image remains in a portrait. The second is his mother “with her arm up, warding off his suspicions.” The third is Little Dorrit “with her hand on the degraded arm and her drooping head turned away.“

Arthur continues to wonder whether his mother “had an old reason… for softening to this poor girl.” With all these thoughts Arthur finally falls asleep. When he awakens the next morning Arthur wonders “what do I owe on this score!”

Thoughts

In what significant ways has the plot been developed in this chapter?

What further questions have been raised in this chapter?

Why did Dickens title this chapter “The Lock?”

The Lock

‘Anyone can go in’ replied the old man plainly; adding by the significance of his emphasis,’ but it is not everyone who can go out.”

OK. I admit it. When I see the above line from the chapter under discussion I think of The Eagles great song “Hotel California.” Does anyone else think this way? The Marshalsea Prison and Hotel California. Just wondering.

And now back to Dickens. The second paragraph of this chapter is a masterpiece of character description. Arthur approaches this shabbily dressed man and asks him what the place before them was. The answer is the Marshalsea prison. When Arthur asks the man if he knows the name Dorrit he discovers that the man he is talking to is Frederick Dorrit, and he is the brother to William Dorrit, Amy's father. Frederick tells Arthur that much of what happens outside the walls of the prison are never recounted to his brother William. Arthur is then conducted inside the prison and to William Dorrit’s cell. There, Arthur sees Little Dorrit preparing supper for her father. Arthur realizes that the food being presented to her father is the food Little Dorrit was given for herself at his mother’s home.

What follows is the ritual of a person being presented to Amy's father, William Dorrit assumes his role of the Father of the Marshalsea and then tells Arthur how seldom people come to the jail without being presented. Next, Arthur is told most people offer a testimonial to the father of the jail. Arthur complies.

A bell is heard ringing which signifies that the jail’s front door will be locked soon. Fanny and Tip enter the room and demand fresh clothes for themselves. Little Dorrit opens an old chest of drawers and hands bundles to her brother and sister. Clearly, Little Dorrit is performing the role of the parent to both her father and her siblings. The prison bells are heard ringing again. Before leaving, Arthur presents a testimonial to William Dorrit. Arthur then assures little Dorrit that he only followed her in order to “endeavour to render you and your family some service.”Arthur tells little Dorrit that he hopes to gain her confidence. In response, little Dorrit says “you are very good sir you speak very earnestly to me - but I wish you had not watched me.”

Thoughts

There is a formality that exists within the walls of the jail. There is also a clear hierarchy of persons and roles Within the jail. How would such an organized approach to an institution be of benefit to both those within the jail and those who visit it?

At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell … oops, I mean Little Dorrit.

Is Arthur simply a good man looking to do good deeds for others?

Is Arthur simply trying to learn more about his own family’s mystery and hopes that Little Dorrit can help him?

Could it be possible that Arthur has an emotional interest in little Dorrit?

What other motives may there be for Arthur’s interest in Little Dorrit?

What follows next in the chapter is Dickens developing more of the background of both Little Dorrit and Mrs. Clennam. We learn that Mrs. Clennam offered Little Dorrit a position within her household. Could it be possible that this is one way Mrs Clennam is trying to pay penance for some previous action or event in her life? In any case, Little Dorrit is concerned that the truth of her residence and background may someday be learned by Mrs. Clennam. More and more, we see Dickens weaving the idea of secrets being held by some and secrets being revealed or sought by others. In the middle of this vortex is Little Dorrit, Arthur, and Mrs Clennam.

The bell for the closing of the jail for the evening is heard again. Too late! The main gate has been locked and Arthur has become, for at least one night, also imprisoned in the Marshalsea. We discussed earlier how imprisonment is a trope in this novel. Here we find layers of mystery and imprisonment. Arthur is seeking the answers to his family’s mystery. For at least this night he is imprisoned in the Marshalsea. As Arthur passes the night in prison there are three images of people that run through his mind. The first is of his father who is dead but his image remains in a portrait. The second is his mother “with her arm up, warding off his suspicions.” The third is Little Dorrit “with her hand on the degraded arm and her drooping head turned away.“

Arthur continues to wonder whether his mother “had an old reason… for softening to this poor girl.” With all these thoughts Arthur finally falls asleep. When he awakens the next morning Arthur wonders “what do I owe on this score!”

Thoughts

In what significant ways has the plot been developed in this chapter?

What further questions have been raised in this chapter?

Why did Dickens title this chapter “The Lock?”

Haha - I hadn't thought of Hotel California, Peter, but it did remind me of another ominous pop culture reference:

Haha - I hadn't thought of Hotel California, Peter, but it did remind me of another ominous pop culture reference:https://youtu.be/0zyeF5JLxY8

I'll be back - still have a bit more to read yet.

Peter wrote: "Dickens makes it clear that Arthur Clennam has an interest in Little Dorrit. How might Dickens further develop this relationship in the novel?"

Peter wrote: "Dickens makes it clear that Arthur Clennam has an interest in Little Dorrit. How might Dickens further develop this relationship in the novel?"I would think this was a romance in the works, if it were not that back in Chapter 3 we learn Arthur has an old sweetheart, recently widowed, and concludes the chapter day-dreaming about her. So maybe his interest in Amy Dorrit is only about honorable gentlemanly patronage. But at this point I feel that could swing either way (old love or Little Dorrit?), and it's nice to be uncertain about how things will work out instead of finding it an obvious conclusion.

Peter wrote: "To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and his siblings all spent time in that prison. Charles, who was 12 at the time, went to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. Most of the young Charles’s wages bought food for his family in jail and Charles was very familiar with the jail, its inmates, and its routines."

Peter wrote: "To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and his siblings all spent time in that prison. Charles, who was 12 at the time, went to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. Most of the young Charles’s wages bought food for his family in jail and Charles was very familiar with the jail, its inmates, and its routines."I knew Dickens's father went to jail for debt, but I didn't realize Dickens went with him! Wow. Thanks for this background, Peter.

I very much enjoyed these chapters, more so than the beginning of the book, which felt kind of clunky to me: too many plot threads heaving themselves into place with too many stereotypical characters. This I liked much better: the focus on the Clennams and the Dorrits narrows the lens and lets the story develop more gently and gradually.

I loved the chapters on the Father and Child of Marshalsea, which felt like fairy tales to me. I am a little nervous about Amy's born-to-self-sacrifice nature (there are too many daughters sacrificing themselves to undeserving fathers/grandfathers in Dickens!), but right now it's balanced out for me by her resilience and by the fascinating "what-if?" Dickens offers us: what if a child were born and raised in a prison? And I loved her relationship with her turnkey godfather, and just the general idea of the prison as a community in its own right, with its own laws and philosophies but also some of the same human nature you find everywhere else.

I do find it confusing that the jailer in the French prison and the turnkey in Marshalsea each have a little girl. As far as we know so far this is coincidence, right? (Although no doubt symbolic coincidence.)

Finally, I found the end of Chapter 8, with Arthur transfixed at the idea of his mother punishing herself to even the score with a hurt she's inflicted on someone else, to be delightfully gothic and creepy--and it's sort of creepy-squared, because we have not only Mrs. C obsessed with a past sin (if Arthur is right), but Arthur obsessed by her obsession. His late-night thoughts in our last installment were about an attractive widow, but now he's up late thinking about his unwholesome mother instead. Not a good direction, Arthur!

Peter wrote: "At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell.”

Peter wrote: "At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell.”A slip of the keystroke, there, Peter, when you referred to Amy as Little Nell. But an easy slip to make, since no father/father figure has irritated me like William Dorrit since Little Nell's grandfather. Both feckless, selfish men who need to stop relying on the kindness and wisdom of the little girls in their lives to get by. Shame on them.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell.”

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell.”A slip of the keystroke, there, Peter, when you referred to Amy as Little Nell. But..."

Ha! I missed that! But I agree 100% on the resemblance.

It seems to me that "the debtor" was not named in chapter 6, and we only found out his connection with the "little girl" later. Interesting that Dickens would leave that information out initially. What were his reasons, I wonder?

It seems to me that "the debtor" was not named in chapter 6, and we only found out his connection with the "little girl" later. Interesting that Dickens would leave that information out initially. What were his reasons, I wonder? I'm also fascinated with the segment Peter referenced about prison being peace. A nanny state indeed! William obviously has anxiety about the outside world and prison is a cocoon for him. And yet, while the big pool makes him uncomfortable, he has no problem being a big fish in the little pond of the Marshalsea. Of course, the "father of the Marshalsea" is not only a title of dubious distinction, it's also meaningless when it comes to William having any real agency. Why do the other prisoners put up with his pretensions, I wonder? And what happened in his life to make him happier in lock-up than having freedom?

Peter, your comparisons of the Marshalsea with Rigaud's and John Baptist's prison experience made me wonder if debtor's prison wasn't more like today's "white collar" detention centers, i.e. a lot less punitive than a prison for violent criminals might be. Dickens certainly does give it a much homier feel. Or is that less Dickens experience, and more through William's eyes?

What does everyone make of Frederick? Is he as feckless as his brother? Why so filthy? I could almost sense the fleas crawling on him, the way Dickens described his lack of hygiene. What has befallen these two brothers, to make them such social pariahs? Despite the filth and the inexplicable request that he makes of Arthur - to go along with the charade that allows William some dignity that he certainly doesn't deserve - I find Frederick likeable so far.

Finally, I cringed for Amy when her father was asking Arthur for a "testimonial". She takes the fourth commandment to extremes, if you ask me.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and his siblings al..."

Hi Julie

My comment about Dickens going to work at the age of twelve while his parents and siblings were in the Marshalsea might suggest Dickens lived in the jail as well. I should have made more clear that Dickens lived outside the jail in a rooming house. Yes, a twelve year old living by himself, going to work at a blacking factory, and then bringing part of his wages to his family in jail. The novel LD cuts deep into Dickens’s own experiences. The name Warren’s Blacking Factory makes a couple of appearances in his novels.

This part of Dickens’s life remained a secret from his own family for decades. It was John Forester, Dickens’s good friend and first biographer, who first revealed the story of the Marshalsea to the general public after Dickens’s death.

Hi Julie

My comment about Dickens going to work at the age of twelve while his parents and siblings were in the Marshalsea might suggest Dickens lived in the jail as well. I should have made more clear that Dickens lived outside the jail in a rooming house. Yes, a twelve year old living by himself, going to work at a blacking factory, and then bringing part of his wages to his family in jail. The novel LD cuts deep into Dickens’s own experiences. The name Warren’s Blacking Factory makes a couple of appearances in his novels.

This part of Dickens’s life remained a secret from his own family for decades. It was John Forester, Dickens’s good friend and first biographer, who first revealed the story of the Marshalsea to the general public after Dickens’s death.

Mary Lou wrote: "Peter wrote: "At this point in the novel let us speculate on Arthur’s interest and motives towards Little Nell.”

A slip of the keystroke, there, Peter, when you referred to Amy as Little Nell. But..."

Mary Lou

Thanks for the catch. Our two little friends do share much in common. As part of our final comments on this novel we should ask who is more annoying — Nell’s grandfather or Amy’s father.

A slip of the keystroke, there, Peter, when you referred to Amy as Little Nell. But..."

Mary Lou

Thanks for the catch. Our two little friends do share much in common. As part of our final comments on this novel we should ask who is more annoying — Nell’s grandfather or Amy’s father.

Peter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and h..."

Peter wrote: "Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "To put this chapter into its historical context we need to remember that Dickens’s father was once imprisoned in the Marshalsea for debt. Dickens’s father, mother, and h..."Thanks for the clarification, and it is very sad that he kept that a secret all his life.

Mary Lou wrote: "It seems to me that "the debtor" was not named in chapter 6, and we only found out his connection with the "little girl" later. Interesting that Dickens would leave that information out initially. ..."

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. Dickens creates a quandary when we see how Mr Dorrit much prefers to live within a jail than without it. The idea at first seems silly. I agree with you that he prefers to be a big fish in a little pond rather than a small fish in the tumult that is London.

In many ways, however, I can see how jail does create a sense of freedom, order, and a recognizable hierarchy that would be very appealing to some.. In jail, one is freed from the responsibilities and expectations of society. In jail, while one’s life is severely regulated, one’s life is also ordered, predictable, and constant. In jail, one’s status is established by time spent incarcerated, not by one’s wealth, title, social position, or government appointment.

When we consider the tumult of the city of London, its pace of life, social expectations, financial demands, political intrigue and, at the same time, political inefficiency one could argue that the Marshalsea is a safe walled island that protects its inhabitants from the chaos that surrounds it every day.

Hi Mary Lou

Yes. Dickens creates a quandary when we see how Mr Dorrit much prefers to live within a jail than without it. The idea at first seems silly. I agree with you that he prefers to be a big fish in a little pond rather than a small fish in the tumult that is London.

In many ways, however, I can see how jail does create a sense of freedom, order, and a recognizable hierarchy that would be very appealing to some.. In jail, one is freed from the responsibilities and expectations of society. In jail, while one’s life is severely regulated, one’s life is also ordered, predictable, and constant. In jail, one’s status is established by time spent incarcerated, not by one’s wealth, title, social position, or government appointment.

When we consider the tumult of the city of London, its pace of life, social expectations, financial demands, political intrigue and, at the same time, political inefficiency one could argue that the Marshalsea is a safe walled island that protects its inhabitants from the chaos that surrounds it every day.

Which one is more annoying, Nell's grandfather or Amy's father? I'm pretty sure that Amy's father is Nell's grandfather brought back to life. I can't stand either of them. And if you are in prison because you are in debt and must stay there until your debts are paid, how are you supposed to earn the money to pay them if you are in prison?

Kim wrote: "And if you are in prison because you are in debt and must stay there until your debts are paid, how are you supposed to earn the money to pay them if you are in prison? "

That's one of the wonderful paradoxes of Victorian life, isn't it? Probably, you were supposed to lend the money you needed from someone else so that you just transferred your debts? Apparently, you still had to pay for your own food in a debtor's prison because why else would Amy smuggle her own food into the Marshalsea to prepare it for her father? Likewise, the prisoners in the first chapter apparently had to pay their own way, and that's why Rigaud's repast was much daintier than the Italian smuggler's.

I am relieved to find that I am not the only one to heartily despise Mr. Dorrit as a feckless, self-righteous, scrounging humbug. He has no idea how he came to be imprisoned, but he does not even try to concentrate, to man up and find out, and by putting up with his circumstances so easily, he consigns his three children to a life in prison, a life in which they have no chance of learning to deal with life as it is outside - and we clearly see the results of this in Tip, who is destined to become a good-for-nothing, some kind of scruffier Richard Carstone, only not so noble-hearted. It is Amy, not her father, who sees to it that Fanny and Tip are getting some kind of education and some kind of opening in life - and this is shameful.

I think that Dr. Haggage sums up most perfectly the attitude of Mr. Dorrit and of probably not few of the inmates of the prison when he says that once inside the Marshalsea they no longer have to worry about life's challenges and iniquities and they are safe from their creditors. This mindset may work well for someone who has no family to depend on him and no children to whom he must set an example - but it is despicable in someone like Mr. Dorrit. In a way, though, the outer prison creates an inner prison, or reinforces it, in these people: namely the prison of learned helplessness, and this is an attitude I often find at school and with some of my family members, luckily neither my wife nor my children. We have a nice expression to deal with this attitude in German, and I sometimes use it with some of my students, who simply say, "I can't do it" and then resign. If you translated it into English, it would be something like: "I cannot lives in I-don't-want-to-Street." Oh, how my son hates this saying ;-)

That's one of the wonderful paradoxes of Victorian life, isn't it? Probably, you were supposed to lend the money you needed from someone else so that you just transferred your debts? Apparently, you still had to pay for your own food in a debtor's prison because why else would Amy smuggle her own food into the Marshalsea to prepare it for her father? Likewise, the prisoners in the first chapter apparently had to pay their own way, and that's why Rigaud's repast was much daintier than the Italian smuggler's.

I am relieved to find that I am not the only one to heartily despise Mr. Dorrit as a feckless, self-righteous, scrounging humbug. He has no idea how he came to be imprisoned, but he does not even try to concentrate, to man up and find out, and by putting up with his circumstances so easily, he consigns his three children to a life in prison, a life in which they have no chance of learning to deal with life as it is outside - and we clearly see the results of this in Tip, who is destined to become a good-for-nothing, some kind of scruffier Richard Carstone, only not so noble-hearted. It is Amy, not her father, who sees to it that Fanny and Tip are getting some kind of education and some kind of opening in life - and this is shameful.

I think that Dr. Haggage sums up most perfectly the attitude of Mr. Dorrit and of probably not few of the inmates of the prison when he says that once inside the Marshalsea they no longer have to worry about life's challenges and iniquities and they are safe from their creditors. This mindset may work well for someone who has no family to depend on him and no children to whom he must set an example - but it is despicable in someone like Mr. Dorrit. In a way, though, the outer prison creates an inner prison, or reinforces it, in these people: namely the prison of learned helplessness, and this is an attitude I often find at school and with some of my family members, luckily neither my wife nor my children. We have a nice expression to deal with this attitude in German, and I sometimes use it with some of my students, who simply say, "I can't do it" and then resign. If you translated it into English, it would be something like: "I cannot lives in I-don't-want-to-Street." Oh, how my son hates this saying ;-)

Do you know the movie The Shawshank Redemption? It's a prison movie, and there is one very old prisoner played by James Whitmore, who spent most of his life in prison and is suddenly released and then finds himself in a world he no longer understands. After a couple of days, this man, who had been the prison librarian and therewith had a task that fulfilled his life and gave it sense, is so lonely and desperate that he commits suicide. - I think the same would happen to Mr. Dorrit if he found himself outside the Marshalsea all of a sudden and didn't have his daugther at his side to rely on.

The various psychologies of a person in prison are as different and intricate as the psychologies of a person who is free and lives outside a prison’s walls. In both cases, the person through experience learns how to cope within their environment or they suffer the consequences.

Let’s consider the Marshalsea prison. Outside its walls is freedom. Each person in every Dickens novel who lives in London (or elsewhere) is in an ecosystem where they live, work, travel, and experience love, hate, fear and every other emotion. Is not this one of the great powers of Dickens? He shows us people in the process of getting along with their lives.

The Marshalsea has an outer courtyard where both visitors to the jail and the prisoners can intermingle. This is the transitional world, a world where overlapping occurs. In psychological terms, it is a transitional place.

Next is the jail itself where prisoners spend their time, their Iives and must create a different ecosystem for survival. In this world is found a place similar to what exists outside the Marshalsea’s walls. Here we also find seamstresses, dancing instructors, doctors and every other sort of occupation.

The way I see it there is little difference between the Barnacles who have power and prestige and live outside the walls of the jail and Mr Dorrit, the Father of the Marshalsea who lives inside the jail. Are they both not people of power, significance, people who are respected for no good reason. Both are barnacles. Ah, Dickens and the way he gives the perfect name to most of his characters. The only real difference is, as I see it, they exist in different ecosystems within the same country. The night Arthur spends in the Marshalsea gives us a look at our protagonist who is a transitional figure between the two worlds. Little Dorrit is a figure who fascinates him. She too is a transitional figure. One of the links between the two is Arthur’s mother's home. Is that home not also a prison? And of course we need to remember that his mother is evidently imprisoned both physically by her wheelchair and mentally by a secret she holds.

Dickens was fascinated with prisons. In American Notes we see how a prison was a top priority to visit during his travels. As we have already noted, this is a novel about imprisonment in multiple ways.

Let’s consider the Marshalsea prison. Outside its walls is freedom. Each person in every Dickens novel who lives in London (or elsewhere) is in an ecosystem where they live, work, travel, and experience love, hate, fear and every other emotion. Is not this one of the great powers of Dickens? He shows us people in the process of getting along with their lives.

The Marshalsea has an outer courtyard where both visitors to the jail and the prisoners can intermingle. This is the transitional world, a world where overlapping occurs. In psychological terms, it is a transitional place.

Next is the jail itself where prisoners spend their time, their Iives and must create a different ecosystem for survival. In this world is found a place similar to what exists outside the Marshalsea’s walls. Here we also find seamstresses, dancing instructors, doctors and every other sort of occupation.

The way I see it there is little difference between the Barnacles who have power and prestige and live outside the walls of the jail and Mr Dorrit, the Father of the Marshalsea who lives inside the jail. Are they both not people of power, significance, people who are respected for no good reason. Both are barnacles. Ah, Dickens and the way he gives the perfect name to most of his characters. The only real difference is, as I see it, they exist in different ecosystems within the same country. The night Arthur spends in the Marshalsea gives us a look at our protagonist who is a transitional figure between the two worlds. Little Dorrit is a figure who fascinates him. She too is a transitional figure. One of the links between the two is Arthur’s mother's home. Is that home not also a prison? And of course we need to remember that his mother is evidently imprisoned both physically by her wheelchair and mentally by a secret she holds.

Dickens was fascinated with prisons. In American Notes we see how a prison was a top priority to visit during his travels. As we have already noted, this is a novel about imprisonment in multiple ways.

Well, where to begin with Mr. Dorrit? Just as the question asks how a debtor is to ever pay his debts in prison, there is also the question which asks how the debtor is to pay for his food and needs while in prison. In Mr. Dorrit's case he does not want his family to go out and work outside the prison (unless I read this wrong) but I wonder where he believes the food comes from that Little Dorrit brings for his supper. But he also does not want Tip to become a debtor also. None of it makes sense to the logical person. My question is what does Mr. Dorrit do with his "testimonials" if he doesn't spend it on his family or his debts.

Well, where to begin with Mr. Dorrit? Just as the question asks how a debtor is to ever pay his debts in prison, there is also the question which asks how the debtor is to pay for his food and needs while in prison. In Mr. Dorrit's case he does not want his family to go out and work outside the prison (unless I read this wrong) but I wonder where he believes the food comes from that Little Dorrit brings for his supper. But he also does not want Tip to become a debtor also. None of it makes sense to the logical person. My question is what does Mr. Dorrit do with his "testimonials" if he doesn't spend it on his family or his debts. Despicable, yes!

I wonder if Dickens is making a deliberate or conscious comparison of Amy to himself, not only that his father was in debtors prison and left him to work in the blacking factory but in another major way. Just as Amy finds a way to learn a skill and use it to support herself (as well as him) and uses her guidance to aid her siblings, Dickens was able to rise above his circumstances and prosper in life. I read somewhere that while he was in the blacking factory, he thought he would never be able to return to school. And who knows if later in the book we may see Amy progress with more skills and education. At this point she seems to be sacrificing herself, especially her health.

I am wondering if this may turn out to be one of my favorite Dickens novels.

Bobbie wrote: "Well, where to begin with Mr. Dorrit? Just as the question asks how a debtor is to ever pay his debts in prison, there is also the question which asks how the debtor is to pay for his food and need..."

Bobbie

I hope that this book does turn out to be a favourite of yours. Your question of where the money goes when Mr. Dorrit gets his testimonials is a good one. After so many years I hope he has invested it well. :-)

Bobbie

I hope that this book does turn out to be a favourite of yours. Your question of where the money goes when Mr. Dorrit gets his testimonials is a good one. After so many years I hope he has invested it well. :-)

I think Mr. Dorret is a lazy bum. We do not have a lot of info about him before he goes to prison but read nothing about his seeking to learn a trade (as Amy does) or trying to do anything within the prison to make money - like the doctor does. His two older children are out doing things. The dancer learned to dance in prison - then got a job outside. Everyone and his brother tried to help the older son - got him jobs and he was so lazy or unwilling to be a good worker (Could he have learned this from his father?) that he could not keep a job. So he became a thief - following the footsteps (in a way) of his father. Go to prison where you do not have to do any work. Amy is the poor dumb one because she just keeps feeding her father her food and helping her brother and sister. She has a skill - she could walk away. Of course, that is not what Dickens wants us to learn. Amy is loyal to her family, mothers them and does not adequately take care of herself. Dickens told us about her shabby clothes and her thin body. She gives her food to her father who is grabbing money from anyone he can - the new inmates and even Amy's friend. The two older children seem not to give the father anything. At least that is what Dickens has told us so far. Maybe we will learn additional things in the future. Remember that Dickens wrote this as a serial so he can add good things later. But so far, I think the father is a bum.

I think Mr. Dorret is a lazy bum. We do not have a lot of info about him before he goes to prison but read nothing about his seeking to learn a trade (as Amy does) or trying to do anything within the prison to make money - like the doctor does. His two older children are out doing things. The dancer learned to dance in prison - then got a job outside. Everyone and his brother tried to help the older son - got him jobs and he was so lazy or unwilling to be a good worker (Could he have learned this from his father?) that he could not keep a job. So he became a thief - following the footsteps (in a way) of his father. Go to prison where you do not have to do any work. Amy is the poor dumb one because she just keeps feeding her father her food and helping her brother and sister. She has a skill - she could walk away. Of course, that is not what Dickens wants us to learn. Amy is loyal to her family, mothers them and does not adequately take care of herself. Dickens told us about her shabby clothes and her thin body. She gives her food to her father who is grabbing money from anyone he can - the new inmates and even Amy's friend. The two older children seem not to give the father anything. At least that is what Dickens has told us so far. Maybe we will learn additional things in the future. Remember that Dickens wrote this as a serial so he can add good things later. But so far, I think the father is a bum.

Then there is Arthur, I'm confused. Arthur followed Amy which wasn't very nice, but he still did it, and is now waiting to ask someone passing by what building it is that she has entered. This got me wondering why he didn't know it was the Marshalsea. I know he has been gone for twenty years, but wouldn't you remember something as big and creepy (that's how I picture it) as a prison? So I went looking for it and found this:

"The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, Surrey (now London), just south of the River Thames. It housed a variety of prisoners over the centuries, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, but it became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London's debtors. Over half the population of England's prisons in the 18th century were in jail because of debt.

Run privately for profit, as were all English prisons until the 19th century, the Marshalsea looked like an Oxbridge college and functioned as an extortion racket. Debtors in the 18th century who could afford the prison fees had access to a bar, shop and restaurant, and retained the crucial privilege of being allowed out during the day, which gave them a chance to earn money for their creditors. Everyone else was crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others, possibly for years for the most modest of debts, which increased as unpaid prison fees accumulated. The poorest faced starvation and, if they crossed the jailers, torture with skullcaps and thumbscrews. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten were dying every 24 hours in the warmer weather.

The prison became known around the world in the 19th century through the writing of the English novelist Charles Dickens, whose father was sent there in 1824, when Dickens was 12, for a debt to a baker. Forced as a result to leave school to work in a factory, Dickens based several of his characters on his experience, most notably Amy Dorrit, whose father is in the Marshalsea for debts so complex no one can fathom how to get him out."

"Southwark was settled by the Romans around 43 CE. It served as an entry point into London from southern England, particularly along Watling Street, the Roman road from Canterbury; this ran into what is now Southwark's Borough High Street and from there north to old London Bridge. The area became known for its travellers and inns, including Geoffrey Chaucer's Tabard Inn. The itinerant population brought with it poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres (including Shakespeare's Globe) and, inevitably, prisons. In 1796 there were five prisons in Southwark – the Clink, King's Bench, Borough Compter, White Lion and the Marshalsea – compared to 18 in London as a whole.

Until the 19th century imprisonment was not viewed as a punishment in itself in England, except for minor offences such as vagrancy. Prisons simply held people until their creditors had been paid or their fate decided by judges; options included execution (ended 1964), flogging (1962), the stocks (1872), the pillory (1830), the ducking stool (1817), joining the military, or penal transportation to America or Australia (1867). In 1774 there were just over 4,000 prisoners in Britain, half of them debtors, out of a population of six million.

Prisoners had to pay rent, feed and clothe themselves and, in the larger prisons, furnish their rooms. One man found not guilty at trial in 1669 was not released because he owed prison fees from his pre-trial confinement, a position supported by the judge, Matthew Hale. Jailers sold food or let out space for others to open shops; the Marshalsea contained several shops and small restaurants. Prisoners with no money or external support faced starvation. If the prison did supply food to its non-paying inmates, it was purchased with charitable donations – donations sometimes siphoned off by the jailers – usually bread and water with a small amount of meat, or something confiscated from elsewhere as unfit for human consumption. Jailers would load prisoners with fetters and other iron, then charge for their removal, known as "easement of irons" (or "choice of irons"); this became known as the "trade of chains."

The Marshalsea occupied two buildings on the same street in Southwark. The first dated back to the 14th century at what would now be 161 Borough High Street, between King Street and Mermaid Court. By the late 16th century the building was crumbling. In 1799 the government reported that it would be rebuilt 130 yards (119 m) south on what is now 211 Borough High Street. Most of the first Marshalsea, as with the second, was taken up by debtors; in 1773 debtors within 12 miles of Westminster could be imprisoned there for a debt of 40 shillings. Jerry White writes that London's poorest debtors were housed in the Marshalsea. Wealthier debtors arranged to be moved –regularly securing their removal from the Marshalsea by writ of habeas corpus –to the Fleet or the King's Bench, both of which were more comfortable. The prison also held a small number of men being tried at the Old Bailey for crimes at sea.

By the 18th century, the prison had separate areas for its two classes of prisoner: the master's side, which housed about 50 rooms for rent, and the common or poor side, consisting of nine small rooms, or wards, into which 300 people were confined from dusk until dawn. Room rents on the master's side were ten shillings a week in 1728, with most prisoners forced to share. Women prisoners who could pay the fees were housed in the women's quarters, known as the oak. The wives, daughters and lovers of male prisoners were allowed to live with them, if someone was paying their way.

Known as the castle by inmates, the prison had a turreted lodge at the entrance, with a side room called the pound, where new prisoners would wait until a room was found for them. The front lodge led to a courtyard known as the park. This had been divided in two by a long narrow wall, so that prisoners from the common side could not be seen by those on the master's side, who preferred not to be distressed by the sight of abject poverty, especially when they might themselves be plunged into it at any moment.

There was a bar run by the governor's wife, and a chandler's shop run in 1728 by a Mr and Mrs Cary, both prisoners, which sold candles, soap and a little food. There was a coffee shop run in 1729 by a long-term prisoner, Sarah Bradshaw, and a steak house called Titty Doll's run by another prisoner, Richard McDonnell, and his wife. There was also a tailor and a barber, and prisoners from the master's side could hire prisoners from the common side to act as their servants.

By all accounts, living conditions in the common side were horrific. In 1639 prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without space to lie down, leading to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a "bull's pizzle" (a whip made from a bull's penis), or tortured with thumbscrews and a skullcap, a vice for the head that weighed 12 lb (5.4 kg).

What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the strong room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadavers awaiting burial and piles of night soil. Dickens described it as, "dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats." One apparently diabetic army officer who died in the strong room – he had been ejected from the common side because inmates had complained about the smell of his urine – had his face eaten by rats within hours of his death, according to a witness.

By 1799 Marshalsea had fallen into a state of decay, and a decision was made to rebuild it 130 yards south. Like the first Marshalsea, the second was notoriously cramped. In 1827, 414 out of its 630 debtors were there for debts under £20; 1,890 people in Southwark were imprisoned that year for a total debt of £16,442. Women debtors were housed in rooms over the tap room. The rooms in the barracks (the men's rooms) were 10 ft. 10 ins (3.3 m) square and 8–9 ft (2.4–2.7 m) high, with a window, wooden floors and a fireplace. Each housed two or three prisoners, and as the rooms were too small for two beds, prisoners had to share. Apart from the bed, prisoners were expected to provide their own furniture. An anonymous witness complained in 1833: "170 persons have been confined at one time within these walls, making an average of more than four persons in each room – which are not ten feet square!!! I will leave the reader to imagine what the situation of men, thus confined, particularly in the summer months, must be like.

Much of the prison business was run by a debtors' committee of nine prisoners and a chair (a position held by Dickens' father). The committee was responsible for imposing fines for rules violations, an obligation they met with enthusiasm. Debtors could be fined for theft; throwing water or filth out of windows or into someone else's room; making noise after midnight; cursing, fighting or singing obscene songs; smoking in the beer room 8–10p. am or 12–2p. pm; defacing the staircase; dirtying the privy seats; stealing newspapers or utensils from the snuggery; urinating in the yard; drawing water before it had boiled; and criticizing the committee.

As dreadful as the Marshalsea could be, it could also be a haven, because it kept the creditors away. Debtors could even arrange to have themselves arrested by a business partner to enter the jail when it suited them. Historian Margot Finn writes that discharge could therefore be used as a punishment; one debtor was thrown out in May 1801 for "making a Noise and disturbance in the prison."

"Trey Philpotts (whoever that is) writes that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s.According to Philpotts, Dickens rarely made mistakes and did not exaggerate; if anything, he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities."

"The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, Surrey (now London), just south of the River Thames. It housed a variety of prisoners over the centuries, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, but it became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London's debtors. Over half the population of England's prisons in the 18th century were in jail because of debt.

Run privately for profit, as were all English prisons until the 19th century, the Marshalsea looked like an Oxbridge college and functioned as an extortion racket. Debtors in the 18th century who could afford the prison fees had access to a bar, shop and restaurant, and retained the crucial privilege of being allowed out during the day, which gave them a chance to earn money for their creditors. Everyone else was crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others, possibly for years for the most modest of debts, which increased as unpaid prison fees accumulated. The poorest faced starvation and, if they crossed the jailers, torture with skullcaps and thumbscrews. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten were dying every 24 hours in the warmer weather.

The prison became known around the world in the 19th century through the writing of the English novelist Charles Dickens, whose father was sent there in 1824, when Dickens was 12, for a debt to a baker. Forced as a result to leave school to work in a factory, Dickens based several of his characters on his experience, most notably Amy Dorrit, whose father is in the Marshalsea for debts so complex no one can fathom how to get him out."

"Southwark was settled by the Romans around 43 CE. It served as an entry point into London from southern England, particularly along Watling Street, the Roman road from Canterbury; this ran into what is now Southwark's Borough High Street and from there north to old London Bridge. The area became known for its travellers and inns, including Geoffrey Chaucer's Tabard Inn. The itinerant population brought with it poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres (including Shakespeare's Globe) and, inevitably, prisons. In 1796 there were five prisons in Southwark – the Clink, King's Bench, Borough Compter, White Lion and the Marshalsea – compared to 18 in London as a whole.

Until the 19th century imprisonment was not viewed as a punishment in itself in England, except for minor offences such as vagrancy. Prisons simply held people until their creditors had been paid or their fate decided by judges; options included execution (ended 1964), flogging (1962), the stocks (1872), the pillory (1830), the ducking stool (1817), joining the military, or penal transportation to America or Australia (1867). In 1774 there were just over 4,000 prisoners in Britain, half of them debtors, out of a population of six million.

Prisoners had to pay rent, feed and clothe themselves and, in the larger prisons, furnish their rooms. One man found not guilty at trial in 1669 was not released because he owed prison fees from his pre-trial confinement, a position supported by the judge, Matthew Hale. Jailers sold food or let out space for others to open shops; the Marshalsea contained several shops and small restaurants. Prisoners with no money or external support faced starvation. If the prison did supply food to its non-paying inmates, it was purchased with charitable donations – donations sometimes siphoned off by the jailers – usually bread and water with a small amount of meat, or something confiscated from elsewhere as unfit for human consumption. Jailers would load prisoners with fetters and other iron, then charge for their removal, known as "easement of irons" (or "choice of irons"); this became known as the "trade of chains."

The Marshalsea occupied two buildings on the same street in Southwark. The first dated back to the 14th century at what would now be 161 Borough High Street, between King Street and Mermaid Court. By the late 16th century the building was crumbling. In 1799 the government reported that it would be rebuilt 130 yards (119 m) south on what is now 211 Borough High Street. Most of the first Marshalsea, as with the second, was taken up by debtors; in 1773 debtors within 12 miles of Westminster could be imprisoned there for a debt of 40 shillings. Jerry White writes that London's poorest debtors were housed in the Marshalsea. Wealthier debtors arranged to be moved –regularly securing their removal from the Marshalsea by writ of habeas corpus –to the Fleet or the King's Bench, both of which were more comfortable. The prison also held a small number of men being tried at the Old Bailey for crimes at sea.

By the 18th century, the prison had separate areas for its two classes of prisoner: the master's side, which housed about 50 rooms for rent, and the common or poor side, consisting of nine small rooms, or wards, into which 300 people were confined from dusk until dawn. Room rents on the master's side were ten shillings a week in 1728, with most prisoners forced to share. Women prisoners who could pay the fees were housed in the women's quarters, known as the oak. The wives, daughters and lovers of male prisoners were allowed to live with them, if someone was paying their way.

Known as the castle by inmates, the prison had a turreted lodge at the entrance, with a side room called the pound, where new prisoners would wait until a room was found for them. The front lodge led to a courtyard known as the park. This had been divided in two by a long narrow wall, so that prisoners from the common side could not be seen by those on the master's side, who preferred not to be distressed by the sight of abject poverty, especially when they might themselves be plunged into it at any moment.

There was a bar run by the governor's wife, and a chandler's shop run in 1728 by a Mr and Mrs Cary, both prisoners, which sold candles, soap and a little food. There was a coffee shop run in 1729 by a long-term prisoner, Sarah Bradshaw, and a steak house called Titty Doll's run by another prisoner, Richard McDonnell, and his wife. There was also a tailor and a barber, and prisoners from the master's side could hire prisoners from the common side to act as their servants.

By all accounts, living conditions in the common side were horrific. In 1639 prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without space to lie down, leading to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a "bull's pizzle" (a whip made from a bull's penis), or tortured with thumbscrews and a skullcap, a vice for the head that weighed 12 lb (5.4 kg).

What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the strong room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadavers awaiting burial and piles of night soil. Dickens described it as, "dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats." One apparently diabetic army officer who died in the strong room – he had been ejected from the common side because inmates had complained about the smell of his urine – had his face eaten by rats within hours of his death, according to a witness.

By 1799 Marshalsea had fallen into a state of decay, and a decision was made to rebuild it 130 yards south. Like the first Marshalsea, the second was notoriously cramped. In 1827, 414 out of its 630 debtors were there for debts under £20; 1,890 people in Southwark were imprisoned that year for a total debt of £16,442. Women debtors were housed in rooms over the tap room. The rooms in the barracks (the men's rooms) were 10 ft. 10 ins (3.3 m) square and 8–9 ft (2.4–2.7 m) high, with a window, wooden floors and a fireplace. Each housed two or three prisoners, and as the rooms were too small for two beds, prisoners had to share. Apart from the bed, prisoners were expected to provide their own furniture. An anonymous witness complained in 1833: "170 persons have been confined at one time within these walls, making an average of more than four persons in each room – which are not ten feet square!!! I will leave the reader to imagine what the situation of men, thus confined, particularly in the summer months, must be like.

Much of the prison business was run by a debtors' committee of nine prisoners and a chair (a position held by Dickens' father). The committee was responsible for imposing fines for rules violations, an obligation they met with enthusiasm. Debtors could be fined for theft; throwing water or filth out of windows or into someone else's room; making noise after midnight; cursing, fighting or singing obscene songs; smoking in the beer room 8–10p. am or 12–2p. pm; defacing the staircase; dirtying the privy seats; stealing newspapers or utensils from the snuggery; urinating in the yard; drawing water before it had boiled; and criticizing the committee.

As dreadful as the Marshalsea could be, it could also be a haven, because it kept the creditors away. Debtors could even arrange to have themselves arrested by a business partner to enter the jail when it suited them. Historian Margot Finn writes that discharge could therefore be used as a punishment; one debtor was thrown out in May 1801 for "making a Noise and disturbance in the prison."

"Trey Philpotts (whoever that is) writes that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit reflects the real prison of the 1820s.According to Philpotts, Dickens rarely made mistakes and did not exaggerate; if anything, he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian sensibilities."

Kim, thanks for the additional info. Helps set the stage and points out how unaware Arthur was/is. So is he evil or just not paying attention? I am not calling him evil yet. And based on the class system at that time, Arthur was quite normal to follow a servant or employee if he wanted to. He was a much higher class than Amy. Although, why did ne not just ask her where she lived? Because Dickens had to get him into the prison to meet her father and find out how awful it really is.

Kim, thanks for the additional info. Helps set the stage and points out how unaware Arthur was/is. So is he evil or just not paying attention? I am not calling him evil yet. And based on the class system at that time, Arthur was quite normal to follow a servant or employee if he wanted to. He was a much higher class than Amy. Although, why did ne not just ask her where she lived? Because Dickens had to get him into the prison to meet her father and find out how awful it really is.

Kim wrote: "Then there is Arthur, I'm confused. Arthur followed Amy which wasn't very nice, but he still did it, and is now waiting to ask someone passing by what building it is that she has entered. This got ..."

Kim, thanks for the details. What a horrid place the Marshalsea is and what a horrid way to treat a person. Dickens certainly sanitized its conditions for the Victorian reading public. It is difficult - if not impossible - to believe a civilized country allowed such a place to exist. That, of course, gives us a greater insight into why Dickens wrote the novel in the first place.

Kim, thanks for the details. What a horrid place the Marshalsea is and what a horrid way to treat a person. Dickens certainly sanitized its conditions for the Victorian reading public. It is difficult - if not impossible - to believe a civilized country allowed such a place to exist. That, of course, gives us a greater insight into why Dickens wrote the novel in the first place.

Peacejanz wrote: "Kim, thanks for the additional info. Helps set the stage and points out how unaware Arthur was/is. So is he evil or just not paying attention? I am not calling him evil yet. And based on the class ..."

Hi Peacejanz

So far Arthur is portrayed as a very naive man. Perhaps Dickens was using him as a model for the general public who were also naive as to the breadth and depth of what was occurring in their own country and under their own noses.

We will have to follow what happens to Arthur. Will he wake up to the horrors around him? What will he do to remedy the situation? Lots of questions yet to be answered.

Hi Peacejanz

So far Arthur is portrayed as a very naive man. Perhaps Dickens was using him as a model for the general public who were also naive as to the breadth and depth of what was occurring in their own country and under their own noses.

We will have to follow what happens to Arthur. Will he wake up to the horrors around him? What will he do to remedy the situation? Lots of questions yet to be answered.

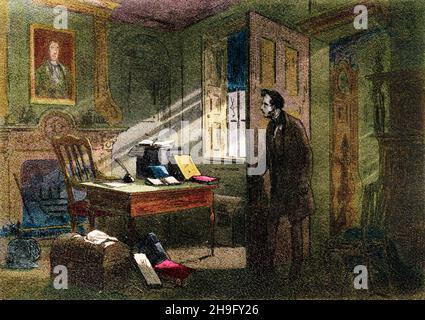

Mr. Flintwinch mediates as a friend of the Family

Chapter 5

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Now," said Jeremiah; "premising that I'm not going to stand between you two, will you let me ask (as I have been called in, and made a third) what is all this about?"

"Take your version of it,' returned Arthur, finding it left to him to speak, "from my mother. Let it rest there. What I have said, was said to my mother only."

"Oh!" returned the old man. "From your mother? Take it from your mother? Well! But your mother mentioned that you had been suspecting your father. That's not dutiful, Mr Arthur. Who will you be suspecting next?"

"Enough," said Mrs Clennam, turning her face so that it was addressed for the moment to the old man only. "Let no more be said about this."

"Yes, but stop a bit, stop a bit," the old man persisted. "Let us see how we stand. Have you told Mr Arthur that he mustn't lay offences at his father's door? That he has no right to do it? That he has no ground to go upon?"

"I tell him so now."

"Ah! Exactly," said the old man. "You tell him so now. You hadn't told him so before, and you tell him so now. Ay, ay! That's right! You know I stood between you and his father so long, that it seems as if death had made no difference, and I was still standing between you. So I will, and so in fairness I require to have that plainly put forward. Arthur, you please to hear that you have no right to mistrust your father, and have no ground to go upon." — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 5, "Family Affairs,".

Commentary: