Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit II: Chapters 23 - 34

message 52:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 18, 2020 07:17AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Poor Arthur! But what a tribute this chapter is to his honour and dignity. His behaviour is that of a true gentleman, and profoundly ethical.

We have returned to the Marshalsea prison, but in a way nobody would have expected, least of all Arthur Clennam. Charles Dickens has turned this story on its head—and even placed him in the same cell that the Dorrit family originally inhabited.

The final words of this chapter “O my Little Dorrit” remind us that we have not heard about Amy Dorrit for a few chapters, our hero is now in prison, and we seem no nearer to solving the the mystery of his family secret!

We have returned to the Marshalsea prison, but in a way nobody would have expected, least of all Arthur Clennam. Charles Dickens has turned this story on its head—and even placed him in the same cell that the Dorrit family originally inhabited.

The final words of this chapter “O my Little Dorrit” remind us that we have not heard about Amy Dorrit for a few chapters, our hero is now in prison, and we seem no nearer to solving the the mystery of his family secret!

For me, the final paragraph is the most poignant of the whole chapter. My heart breaks for Arthur in this moment but his calling out to her, to My Little Dorrit, I hope, is the beginning of his recognizing his love for her.

For me, the final paragraph is the most poignant of the whole chapter. My heart breaks for Arthur in this moment but his calling out to her, to My Little Dorrit, I hope, is the beginning of his recognizing his love for her. She is on her way back to London soon. I'm sure that she will come to him as soon as she hears about Arthur's fate. She still loves him, of course,, and money means nothing to her. She could move right in with him in her old home, and be very happy.

Arthur takes all the liability for the partnerships' debts himself to their suppliers/creditors since he has lost all the capital. So that Doyce won't be pursued. Technically he didn't do anything wrong really but the creditors want some satisfaction and I guess that's all they had then was to throw someone in debtors' prison and make them pay eventually if they can get some money somehow.

Arthur takes all the liability for the partnerships' debts himself to their suppliers/creditors since he has lost all the capital. So that Doyce won't be pursued. Technically he didn't do anything wrong really but the creditors want some satisfaction and I guess that's all they had then was to throw someone in debtors' prison and make them pay eventually if they can get some money somehow.Sorry to see the part with the drunken Jew who says "madder ob bithznithz."

It's very touching that Arthur is taken to stay in the Dorrit family's old room, isn't it? It's a full circle, he didn't deserve it, but here he is.

I wonder if the title Nobody's Fault starts to make sense in light of these developments? Or does anyone else have a different take on that title?

Mark,

Mark, I was thinking about the title as well. I don't understand why "Nobody's Fault" was chosen initially. Re: the financial crisis, it is Merdle's fault. But maybe Dickens had in mind that he was a product of the society in which he lived so even what he did wasn't his fault. With that reasoning then none of the characters would be responsible for any of their actions. But Dickens was critical of all that he satirizes in this book so the title was probably meant to be ironic.

message 56:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 18, 2020 09:47AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark - "Sorry to see the part with the drunken Jew who says "madder ob bithznithz." Well it is a mere four lines, so doesn't even merit being called a cameo, really.

I think we are taken aback nowadays, but may be too sensitive. Is it any different from the other mannerisms we see?

There's Mr. William Dorrit with his "er... hum"s, Edmund Sparkler and his "no biggod nonsense" - both of these are class-based. Then there's Pancks with his steam engine noises, Mr. Meagles with his "Allongers and Marshongers", Mrs. Merdle with her "personally charmed" ... and the very peculiar language Mrs. Plornish employs with "Mr. Baptist" (Cavalletto), is a reverse stereotype, as he actually corrects the English syntax as he replies! Mrs. General has her "prunes and prisms"s. Even Little Dorrit's habitual mantra when young was "Please Sir/Madam, I was born here".

All of these and more display the way an individual presents themselves to society, and this is partly choice, and partly influenced to a certain degree by their social and ethnic group. Charles Dickens observes it very well.

No, I don't think on balance there is anything objectionable about this. Charles Dickens created Mr. Riah, one of my favourite characters in Our Mutual Friend, as a very positive benevolent, intelligent character, precisely to obvert any accusation of antisemitism.

I think we are taken aback nowadays, but may be too sensitive. Is it any different from the other mannerisms we see?

There's Mr. William Dorrit with his "er... hum"s, Edmund Sparkler and his "no biggod nonsense" - both of these are class-based. Then there's Pancks with his steam engine noises, Mr. Meagles with his "Allongers and Marshongers", Mrs. Merdle with her "personally charmed" ... and the very peculiar language Mrs. Plornish employs with "Mr. Baptist" (Cavalletto), is a reverse stereotype, as he actually corrects the English syntax as he replies! Mrs. General has her "prunes and prisms"s. Even Little Dorrit's habitual mantra when young was "Please Sir/Madam, I was born here".

All of these and more display the way an individual presents themselves to society, and this is partly choice, and partly influenced to a certain degree by their social and ethnic group. Charles Dickens observes it very well.

No, I don't think on balance there is anything objectionable about this. Charles Dickens created Mr. Riah, one of my favourite characters in Our Mutual Friend, as a very positive benevolent, intelligent character, precisely to obvert any accusation of antisemitism.

message 57:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 18, 2020 09:44AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Anne - (and Mark's thought) "maybe Dickens had in mind that he was a product of the society in which he lived so even what he did wasn't his fault ..."

I like this. Arthur Clennam is preoccupied with the idea of blame, and guilt for nearly all the novel. But there are many strands of story which "Nobody's Fault" could apply to. I also like the beginning parts, where Arthur himself was quite deliberately referred to as "Nobody". There is a sense in which every individual is a nobody.

I like this. Arthur Clennam is preoccupied with the idea of blame, and guilt for nearly all the novel. But there are many strands of story which "Nobody's Fault" could apply to. I also like the beginning parts, where Arthur himself was quite deliberately referred to as "Nobody". There is a sense in which every individual is a nobody.

Arthur is an amazingly upright man as is Pancks. I am interested to see how Pancks and Amy react to his imprisonment, and how it afffects The Bosom and Fanny and Edmund. While I do feel bad, I also feel that things cant help but work out!

Arthur is an amazingly upright man as is Pancks. I am interested to see how Pancks and Amy react to his imprisonment, and how it afffects The Bosom and Fanny and Edmund. While I do feel bad, I also feel that things cant help but work out!

Anne,

Anne,I see your point. Dickens does refer to this speculation as an epidemic, a plague, a fire that consumes as much as it can.

I wonder how many of these investing debacles happened back then. Mr Merdle was based on an historical figure. We know about these things nowadays (they still happen). Enron went from $90 per share down to $0.25. Poor investors and company stock people! Same for Lehman Bros 2008 meltdown that hurt the economy so much.

I wonder if this was a "novel" event of capitalism in Dickens' time that seemed so special and bizarre and widespread that Dickens wanted to make it a central event of this novel and not just a plot point.

message 61:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 18, 2020 11:38AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark wrote: "I wonder if this was a "novel" event of capitalism in Dickens' time that seemed so special and bizarre and widespread that Dickens wanted to make it a central event of this novel and not just a plot point ..."

Since John Sadleir's suicide was on 17th February 1856, bang in the middle of the Little Dorrit serialisation (1855-57) this is certainly true. For the early parts of the novel Charles Dickens will have been glued to the News as it unfolded, pretty much as everyone else in England would have been.

And a bit later in chapter 28, Charles Dickens makes a more general comment on this phenomenon ... but I'll highlight that when we come to it :)

Since John Sadleir's suicide was on 17th February 1856, bang in the middle of the Little Dorrit serialisation (1855-57) this is certainly true. For the early parts of the novel Charles Dickens will have been glued to the News as it unfolded, pretty much as everyone else in England would have been.

And a bit later in chapter 28, Charles Dickens makes a more general comment on this phenomenon ... but I'll highlight that when we come to it :)

Much is happening. Suicide, Arthur in debtors prison. So many people's fate unknown. What is going to happen with everyone?

Much is happening. Suicide, Arthur in debtors prison. So many people's fate unknown. What is going to happen with everyone? And what is in the box!

This story is not going at all like I expected. And that is a good thing.

message 63:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 21, 2020 09:04AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 27:

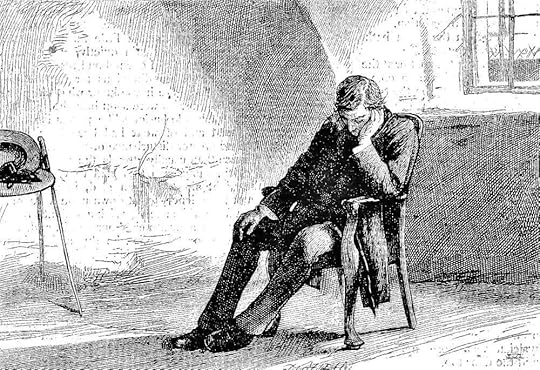

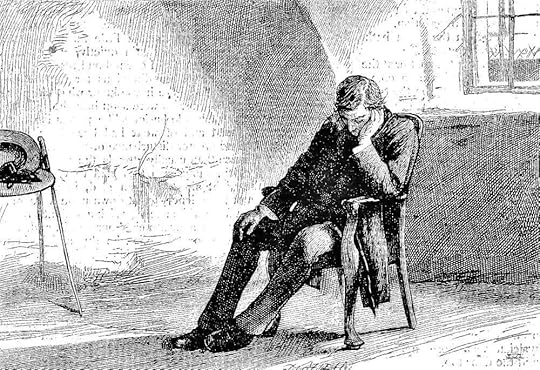

The next installment begins back in the Marshalsea Prison, where Arthur Clennam is now an inmate and no longer just a visitor:

'The Day was Sunny' - James Mahoney

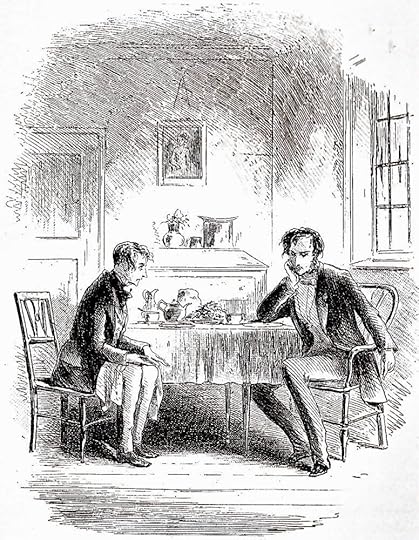

At first he has a sense of peace, as most new inmates do, but this does not last for long. Soon his spirits sink very low, not only because of his present position, but also because his memory of the prison room reminds him of Little Dorrit.

“Yet it was remarkable to him; not because of the fact itself, but because of the reminder it brought with it, how much the dear little creature had influenced his better resolutions.”

The narrator comments that none of us aware of who has influenced us for the better, until later, perhaps in times of adversity. Arthur now realises how good an example Little Dorrit had been to him:

“whom had I before me, toiling on, for a good object’s sake, without encouragement, without notice, against ignoble obstacles that would have turned an army of received heroes and heroines? One weak girl! … in whom … I watched patience, self-denial, self-subdual, charitable construction, the noblest generosity of the affections”.

So Arthur sits alone in the faded chair, always thinking about Little Dorrit. He does not hear a knock at the door, even though it comes half a dozen times; he has been thinking for hours. It is the turnkey Mr. Chivery, to ask if he can do anything for him. Arthur Clennam’s things have arrived and Younng John will carry them up to his room. He then goes on to say something mysterious before he leaves, which Arthur does not understand:

“Mr Clennam, don’t you take no notice of my son (if you’ll be so good) in case you find him cut up anyways difficult. My son has a ‘art, and my son’s ‘art is in the right place. Me and his mother knows where to find it, and we find it sitiwated correct.”

Young John Chivery arrives, and sure enough he is acting in a most peculiar manner, and refuses to shake hands. Arthur is baffled, and says if he has offended Young John somehow, he is sorry. Young John says that he would fight Arthur, if their weights were more equal, and they were not in the Marshalsea, where it is not allowed.

Then obviously conflicted, he begs Arthur’s pardon, and explains that all the furniture on the room is his own, which he usually rents out, but that he will not accept any money for it. Once more, Arthur asks what is the matter, but Young John refuses to say. Instead, he talks about the round table, which used to belong to someone who “died a great gentleman”, and whom he had visited in London:

“On the whole he was of opinion that it was an intrusion … I asked him if Miss Amy was well—”.

When Arthur asks about the answer, Young John is surprised that he does not know it already. After a while’s silence, he asks whether Arthur would take a cup of tea in his apartment, since he had not eaten or drunk anything. They make their way up to Young John’s room, and Arthur:

“foresaw where they were going as soon as their feet touched the staircase. The room was so far changed that it was papered now, and had been repainted, and was far more comfortably furnished; but he could recall it just as he had seen it in that single glance, when he raised her from the ground and carried her down to the carriage.”

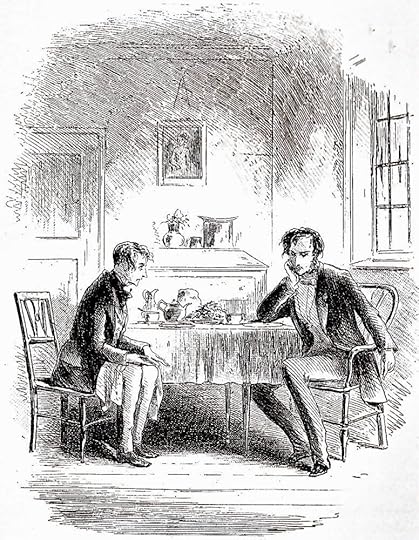

Arthur is full of sad thoughts, remembering Little Dorrit, while Young John fetches some things for tea. He chooses tasty morsels, including something green and fresh, trying to tempt Arthur to eat.

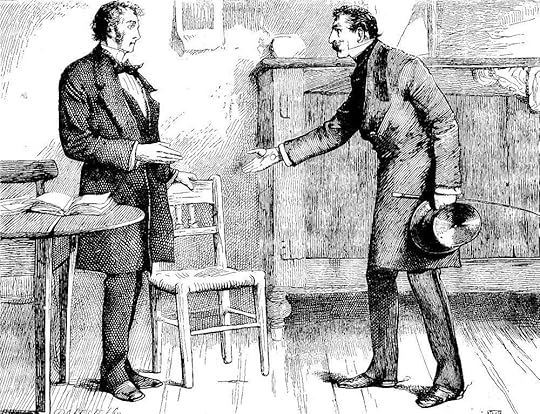

'At Young John Chivery's Teatable' - Phiz

After a while he says:

“I wonder … that if it’s not worth your while to take care of yourself for your own sake, it’s not worth doing for some one else’s””

But Arthur does not know who he can mean. Young John is very reproachful at this,considering it to be a further insult. He becomes so emotional that his words tumble out in confusion, as he uses his mother’s unusual word order. He says that he had managed to conquer his passion, until he saw Arthur:

“I shouldn’t have given my mind to it again, I hope, if to this prison you had not been brought, and in an hour unfortunate for me, this day!” He says he had struggled hard to be polite to Arthur, and “when I’ve been so wishful to show that one thought is next to being a holy one with me and goes before all others” and yet Arthur has not said anything, even when John hinted so hard.

“It’s all very well to trample on it, but it’s there. It may be that it couldn’t be trampled upon if it wasn’t there. But that doesn’t make it gentlemanly, that doesn’t make it honourable … The world may sneer at a turnkey, but he’s a man—when he isn’t a woman, which among female criminals he’s expected to be.”

Arthur is completely baffled, but sees that Young John is agitated and feels wounded by something he has said. He thinks back to what it might be, and surmises that it might be Miss Dorrit, and says he had not meant to cause any offence.

“‘Sir,’ said Young John, ‘will you have the perfidy to deny that you know and long have known that I felt towards Miss Dorrit, call it not the presumption of love, but adoration and sacrifice?’”

Arthur says that yes, he had known, but had Miss Dorrit’s happiness as his aim. If had had thought that Miss Dorrit returned his affection … But Young John was quick to assure him, with great chivalry and sorrow that she never had returned his affections.

“‘You speak, John,’ he said, with cordial admiration, ‘like a Man.’

‘Well, sir,’ returned John, brushing his hand across his eyes, ‘then I wish you’d do the same.’“

Still Arthur does not see. After a sarcastic exchange, Young John comes to an astounding realisation:

“John’s incredulous face slowly softened into a face of doubt …‘Mr Clennam, do you mean to say that you don’t know?’”

As gently as he can, he tells him that Miss Dorrit had loved Arthur, and Arthur is no less amazed, and feels as if he has been dealt a blow. He takes his leave of Young John, and goes back to his own.

“Little Dorrit love him! More bewildering to him than his misery, far.

Consider the improbability. He had been accustomed to call her his child, and his dear child, and to invite her confidence by dwelling upon the difference in their respective ages, and to speak of himself as one who was turning old. Yet she might not have thought him old. Something reminded him that he had not thought himself so, until the roses had floated away upon the river.“

Arthur takes out the two letters Little Dorrit had sent to him, and reads them with this new idea in his mind. Could it be true?

And further to this, a new idea occurs to him. Had he deliberately pushed away any such thoughts himself, believing that he must not take advantage of her gratitude, and must help her to love someone else, that such thoughts were no longer for him, that he was too saddened and old.

And he remembers how he had kissed her when she had fainted, and wonders.

After dark, while he still muses, Mr. and Mrs. Plornish come, and break the spell with their good humour, and choice foods. They tell him that Old Nandy cannot sing a note, as he is so upset, and Mr. Baptist is still chasing up the confidential business that Mr. Clennam had asked him to, or he would certainly be there. She also says:

“It’s a thing to be thankful for, indeed, that Miss Dorrit is not here to know it

… that Miss Dorrit is far away. It’s to be hoped she is not likely to hear of it. If she had been here to see it, sir, it’s not to be doubted that the sight of you—in misfortune and trouble, would have been almost too much for her affectionate heart. There’s nothing I can think of, that would have touched Miss Dorrit so bad as that.“

And after the couple have gone, Arthur Clennam thinks of Little Dorrit for hours on end. Everything seems to have led to Little Dorrit. He should be glad that she was quite of this place, far away, and likely soon to be married like her sister. Otherwise, she would have been brought back to this place, with him. “Dear Little Dorrit.”

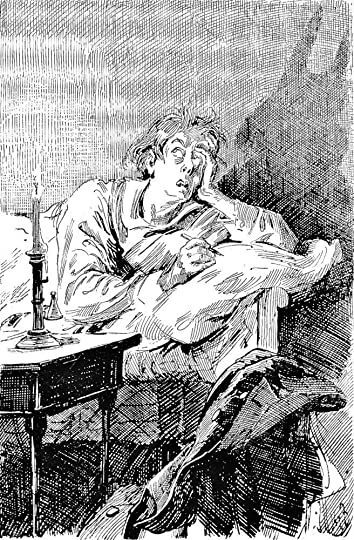

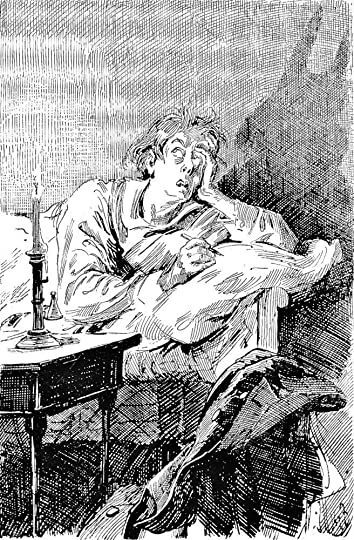

And as he spends all night with these thoughts, Young John in his own room composes another epitaph, in which he encounters his rival, and is tempted to fight him, but for the sake of the one he loves “conquered those feelings of bitterness, and became magnanimous”.

'Young John Prepares his own Epitaph' - Harry Furniss

The Marshalsea Prison Wall, as it now is

The next installment begins back in the Marshalsea Prison, where Arthur Clennam is now an inmate and no longer just a visitor:

'The Day was Sunny' - James Mahoney

At first he has a sense of peace, as most new inmates do, but this does not last for long. Soon his spirits sink very low, not only because of his present position, but also because his memory of the prison room reminds him of Little Dorrit.

“Yet it was remarkable to him; not because of the fact itself, but because of the reminder it brought with it, how much the dear little creature had influenced his better resolutions.”

The narrator comments that none of us aware of who has influenced us for the better, until later, perhaps in times of adversity. Arthur now realises how good an example Little Dorrit had been to him:

“whom had I before me, toiling on, for a good object’s sake, without encouragement, without notice, against ignoble obstacles that would have turned an army of received heroes and heroines? One weak girl! … in whom … I watched patience, self-denial, self-subdual, charitable construction, the noblest generosity of the affections”.

So Arthur sits alone in the faded chair, always thinking about Little Dorrit. He does not hear a knock at the door, even though it comes half a dozen times; he has been thinking for hours. It is the turnkey Mr. Chivery, to ask if he can do anything for him. Arthur Clennam’s things have arrived and Younng John will carry them up to his room. He then goes on to say something mysterious before he leaves, which Arthur does not understand:

“Mr Clennam, don’t you take no notice of my son (if you’ll be so good) in case you find him cut up anyways difficult. My son has a ‘art, and my son’s ‘art is in the right place. Me and his mother knows where to find it, and we find it sitiwated correct.”

Young John Chivery arrives, and sure enough he is acting in a most peculiar manner, and refuses to shake hands. Arthur is baffled, and says if he has offended Young John somehow, he is sorry. Young John says that he would fight Arthur, if their weights were more equal, and they were not in the Marshalsea, where it is not allowed.

Then obviously conflicted, he begs Arthur’s pardon, and explains that all the furniture on the room is his own, which he usually rents out, but that he will not accept any money for it. Once more, Arthur asks what is the matter, but Young John refuses to say. Instead, he talks about the round table, which used to belong to someone who “died a great gentleman”, and whom he had visited in London:

“On the whole he was of opinion that it was an intrusion … I asked him if Miss Amy was well—”.

When Arthur asks about the answer, Young John is surprised that he does not know it already. After a while’s silence, he asks whether Arthur would take a cup of tea in his apartment, since he had not eaten or drunk anything. They make their way up to Young John’s room, and Arthur:

“foresaw where they were going as soon as their feet touched the staircase. The room was so far changed that it was papered now, and had been repainted, and was far more comfortably furnished; but he could recall it just as he had seen it in that single glance, when he raised her from the ground and carried her down to the carriage.”

Arthur is full of sad thoughts, remembering Little Dorrit, while Young John fetches some things for tea. He chooses tasty morsels, including something green and fresh, trying to tempt Arthur to eat.

'At Young John Chivery's Teatable' - Phiz

After a while he says:

“I wonder … that if it’s not worth your while to take care of yourself for your own sake, it’s not worth doing for some one else’s””

But Arthur does not know who he can mean. Young John is very reproachful at this,considering it to be a further insult. He becomes so emotional that his words tumble out in confusion, as he uses his mother’s unusual word order. He says that he had managed to conquer his passion, until he saw Arthur:

“I shouldn’t have given my mind to it again, I hope, if to this prison you had not been brought, and in an hour unfortunate for me, this day!” He says he had struggled hard to be polite to Arthur, and “when I’ve been so wishful to show that one thought is next to being a holy one with me and goes before all others” and yet Arthur has not said anything, even when John hinted so hard.

“It’s all very well to trample on it, but it’s there. It may be that it couldn’t be trampled upon if it wasn’t there. But that doesn’t make it gentlemanly, that doesn’t make it honourable … The world may sneer at a turnkey, but he’s a man—when he isn’t a woman, which among female criminals he’s expected to be.”

Arthur is completely baffled, but sees that Young John is agitated and feels wounded by something he has said. He thinks back to what it might be, and surmises that it might be Miss Dorrit, and says he had not meant to cause any offence.

“‘Sir,’ said Young John, ‘will you have the perfidy to deny that you know and long have known that I felt towards Miss Dorrit, call it not the presumption of love, but adoration and sacrifice?’”

Arthur says that yes, he had known, but had Miss Dorrit’s happiness as his aim. If had had thought that Miss Dorrit returned his affection … But Young John was quick to assure him, with great chivalry and sorrow that she never had returned his affections.

“‘You speak, John,’ he said, with cordial admiration, ‘like a Man.’

‘Well, sir,’ returned John, brushing his hand across his eyes, ‘then I wish you’d do the same.’“

Still Arthur does not see. After a sarcastic exchange, Young John comes to an astounding realisation:

“John’s incredulous face slowly softened into a face of doubt …‘Mr Clennam, do you mean to say that you don’t know?’”

As gently as he can, he tells him that Miss Dorrit had loved Arthur, and Arthur is no less amazed, and feels as if he has been dealt a blow. He takes his leave of Young John, and goes back to his own.

“Little Dorrit love him! More bewildering to him than his misery, far.

Consider the improbability. He had been accustomed to call her his child, and his dear child, and to invite her confidence by dwelling upon the difference in their respective ages, and to speak of himself as one who was turning old. Yet she might not have thought him old. Something reminded him that he had not thought himself so, until the roses had floated away upon the river.“

Arthur takes out the two letters Little Dorrit had sent to him, and reads them with this new idea in his mind. Could it be true?

And further to this, a new idea occurs to him. Had he deliberately pushed away any such thoughts himself, believing that he must not take advantage of her gratitude, and must help her to love someone else, that such thoughts were no longer for him, that he was too saddened and old.

And he remembers how he had kissed her when she had fainted, and wonders.

After dark, while he still muses, Mr. and Mrs. Plornish come, and break the spell with their good humour, and choice foods. They tell him that Old Nandy cannot sing a note, as he is so upset, and Mr. Baptist is still chasing up the confidential business that Mr. Clennam had asked him to, or he would certainly be there. She also says:

“It’s a thing to be thankful for, indeed, that Miss Dorrit is not here to know it

… that Miss Dorrit is far away. It’s to be hoped she is not likely to hear of it. If she had been here to see it, sir, it’s not to be doubted that the sight of you—in misfortune and trouble, would have been almost too much for her affectionate heart. There’s nothing I can think of, that would have touched Miss Dorrit so bad as that.“

And after the couple have gone, Arthur Clennam thinks of Little Dorrit for hours on end. Everything seems to have led to Little Dorrit. He should be glad that she was quite of this place, far away, and likely soon to be married like her sister. Otherwise, she would have been brought back to this place, with him. “Dear Little Dorrit.”

And as he spends all night with these thoughts, Young John in his own room composes another epitaph, in which he encounters his rival, and is tempted to fight him, but for the sake of the one he loves “conquered those feelings of bitterness, and became magnanimous”.

'Young John Prepares his own Epitaph' - Harry Furniss

The Marshalsea Prison Wall, as it now is

This is quite a chapter! So many feelings pouring out.

This is quite a chapter! So many feelings pouring out.My two favorite parts are, first, John absent-mindedly folding the cabbage leaf up into tiny and tinier shapes and then flattening them again while he sat there.

That is such a nice touch. In Our Mutual Friend Dickens has one character staring off into space twirling her umbrella and it's an awful situation she's facing. These simple gestures I think are great at indicating the characters are lost in their dilemmas but are trying to contain themselves. A very small action that conveys so much intensity. And both using their fingers very precisely.

The other part I loved was this sentence near the end of the chapter,

"Looking back upon his own poor story, she was its vanishing point. Everything in its perspective led to her innocent figure."

Wow. I bet Edith Wharton would have wished she had come up with that in The Age of Innocence if she was aware of it for Newland Archer to realize.

One of my favorite lines from any novel. Granted it's a bit cerebral, but still an amazing image for Dickens to invent.

message 65:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 19, 2020 12:06PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark wrote: "John absent-mindedly folding the cabbage leaf up into tiny and tinier shapes and then flattening them again..."

Yes, as we keep noticing, Charles Dickens is so very skilled at observing human behaviour - even down to these displacement activities.

The quotation you select is indeed profound. Thank you for posting it, Mark :)

Yes, as we keep noticing, Charles Dickens is so very skilled at observing human behaviour - even down to these displacement activities.

The quotation you select is indeed profound. Thank you for posting it, Mark :)

Arthur finally understands that Little Dorrit (which he is still calling her) loves him. Little Dorrit would probably be fine living in debtors prison as long as she was with Arthur.

Arthur finally understands that Little Dorrit (which he is still calling her) loves him. Little Dorrit would probably be fine living in debtors prison as long as she was with Arthur.

These last two chapters are very emotionally charged. It is so difficult to see Arthur, the man who spent so much of his time trying to save others, Dorrit and his family, Cavalletto, even Doyle's invention, locked up in the Marshalsea for debt. My admiration for him just grew with his reaction to this very adverse event.

These last two chapters are very emotionally charged. It is so difficult to see Arthur, the man who spent so much of his time trying to save others, Dorrit and his family, Cavalletto, even Doyle's invention, locked up in the Marshalsea for debt. My admiration for him just grew with his reaction to this very adverse event. I do feel sorry for John and I must say I am glad he has opened Arthur's eyes to Amy's feelings. I he ever indicates to her that the feeling is mutual, she will accept him in any condition she happens to find him in. In fact, if all her money is not lost, she would gladly give it all to clear his debt.

Sara, thanks for reminding me about the invention! I wonder it is that Doyce invented, and how he is getting along in the foreign country he went to!

Sara, thanks for reminding me about the invention! I wonder it is that Doyce invented, and how he is getting along in the foreign country he went to!

Excuse me if Jean or someone else has already suggested this - I was absent for a bit from the discussions - so apologies if this is old info.

Excuse me if Jean or someone else has already suggested this - I was absent for a bit from the discussions - so apologies if this is old info.Speaking of the country Doyce went to (Chapter XXII - Who passes by this road so late?), my edition has this note at the end about the "Barbaric Power" --

"Barbaric Power: Tsarist Russia, generally seen by the early- and mid-nineteenth century British press as a ruthless autocracy governing barbaric peasants. . [long description of the politics of Russia and Britain here]... despite the rivalry between Britain and Russia in the early decades of the century: a handful of British engineers went to Russia to work. William Handyside, one of the most notable of these engineers, designed machinery for the imperial arsenal and glass-works, built four suspension bridges, and, most memorably, produced the stone and metal work for the cathedral of St. Isaac in St. Petersburg, including a colonnade of forty-eight granite pillars."

Jenny wrote: "Sara, thanks for reminding me about the invention! I wonder it is that Doyce invented, and how he is getting along in the foreign country he went to!"

Jenny wrote: "Sara, thanks for reminding me about the invention! I wonder it is that Doyce invented, and how he is getting along in the foreign country he went to!"I'm also wondering when he will find out about Arthur's misfortune and how he will react to having lost all his own money in this unwise investment.

Mark - Thanks for the interesting information.

This chapter brings out the best in both John and Arthur.

This chapter brings out the best in both John and Arthur.I really liked John's new epitaph at the end of the chapter. I'm glad he decided to die at an advanced age and that he is feeling "magnanimous". Life is starting to look better for him.

There are still questions to be answered in this story with only a few chapters remaining. How has the loss of the Merdle fortune affected the Dorrits? What was in Mr. Dorrit's will, or does it matter anymore? Where is Blandois? What is Mrs. Clennam's secret? What is to become of Arthur? I'm sure there are a few more. I am anxious to see how it all plays out.

message 72:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 11:10AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark - There's no need at all to apologise - life happens! And that information about the "barbaric power" was more specific, and interesting, than any I'd managed to discover, so thank you!

Katy - I always feel so very sorry for sensitive, well-meaning Young John Chivery, as he has a raw deal in life. But your comment has made me wonder if he has matured a little through the course of this novel, and can adapt to his situation more. So as you observe, he may begin to feel life is generally better :)

Yes - all good questions - and more too! It's hard to see how they will all be resolved, but I have no doubt they will. The mysteries in this novel are most complex.

Katy - I always feel so very sorry for sensitive, well-meaning Young John Chivery, as he has a raw deal in life. But your comment has made me wonder if he has matured a little through the course of this novel, and can adapt to his situation more. So as you observe, he may begin to feel life is generally better :)

Yes - all good questions - and more too! It's hard to see how they will all be resolved, but I have no doubt they will. The mysteries in this novel are most complex.

message 73:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 11:20AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 28:

A long, busy chapter, in which many characters we know meet together, really moving towards tying up all the threads.

Arthur has been in the Marshalsea for a while, but has not socialised very much:

“Imprisonment began to tell upon him. He knew that he idled and moped … Anybody might see that the shadow of the wall was dark upon him.”

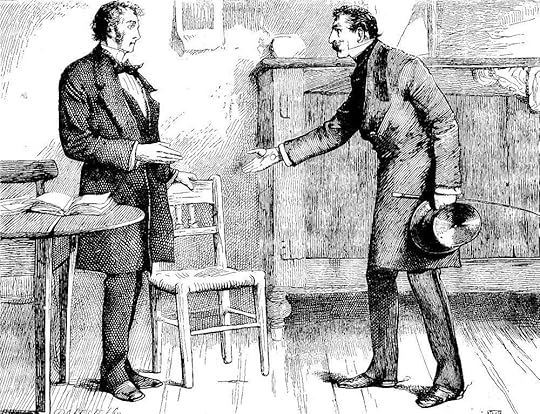

When he has been there for almost three months, he is much surprised by a visit from the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand:

'It was the Sprightly Young Barnacle' - James Mahoney

Ferdinand Barnacle is keen to say that he hopes “our place”, (the Circumlocution Office) has nothing to do with Arthur’s imprisonment, and is pleased when Arthur assures him they have not. Once again the engaging chap tries to explain the Circumlocution Office’s function:

“You’ll say we are a humbug. I won’t say we are not; but all that sort of thing is intended to be, and must be. Don’t you see?’ … we only ask you to leave us alone, and we are as capital a Department as you’ll find anywhere.”

But despite several attempts to express this thought in different ways, and that “Everybody is ready to dislike and ridicule any invention”, he cannot get Arthur to agree. He asks whether it is due to Mr. Merdle that Arthur has been imprisoned:

“‘He must have been an exceedingly clever fellow … A consummate rascal, of course, …but remarkably clever! One cannot help admiring the fellow. Must have been such a master of humbug. Knew people so well-got over them so completely-did so much with them!’…

In his easy way, he was really moved to genuine admiration.“

And breezy, light-hearted and charming as ever, the engaging young Barnacle goes off to mount his horse, and rides off to his next appointment.

Arthur’s next visitor is Mr. Rugg who urges Arthur to move to the “Kings Bench Prison”, as it would be much more fitting to a man in his position. He says that even his daughter, as the plaintiff in Rugg and Bawkins, had expressed her surprise at hearing he was there. After attempting to change his mind by persuasion and then sarcasm, and still finding Arthur unmoved on the subject, he takes his leave, offended and in high dudgeon, and showing in a “military man” on the way out.

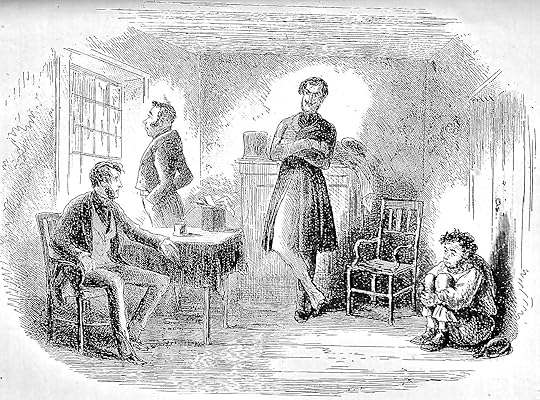

Who should this be, but Blandois! And Blandois in a company we have not seen before: Cavalletto and Pancks. Arthur had thought he recognised the sound of the “display of stride and clatter meant to be insulting” and watches as Cavelletto takes up a seated guarding position by the door, and Pancks stares out of the window.

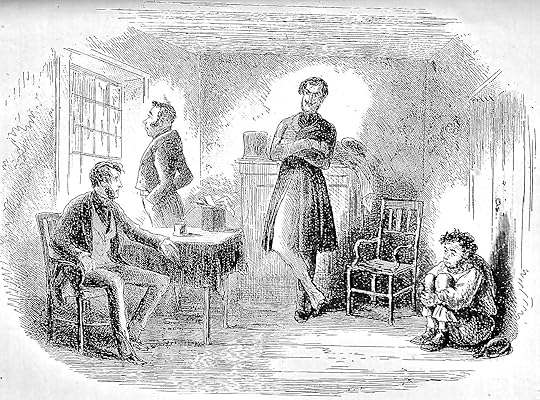

'In the Old Room' - Phiz

There follows a long conversation, with Blandois at his most “impudent and wicked”, swaggering and crafty. Eventually we get to the nub:

“‘I want to know,’ returned Arthur, without disguising his abhorrence, ‘how you dare direct a suspicion of murder against my mother’s house? … I want that suspicion to be cleared away … I want to know, moreover, what business you had there when I had a burning desire to fling you down-stairs … I have seen enough of you to know that you are a bully and coward.’”

But after all Blandois’ insolence and bluster, we and Arthur are no nearer to solving the mystery, or as Blandois terms it the “game”.

We know that Blandois claims to have a commodity to sell Arthur’s mother, and that because she vexed him, and did not immediately accept this, he had decided to disappear for a while. He says that Arthur’s mother and Flintwinch would have been pleased enough to make sure of this themselves. Exceedingly pleased with the worry that his disappearance caused, he stayed away, until Cavalletto had discovered him on Arthur’s behalf, disguised as an old soldier. Perhaps, Blandois suggests “with his horrible smile”, it would have been better to leave him alone? But Arthur says he wants his two friends to keep an eye on Blandois, until he can be brought to justice.

This annoys Blandois, who says “You have interrupted my little project” but lets it pass. “After some villainous thinking and smiling”, he writes an arrogant and outrageous letter to Mrs. Clennam, referring to their “little proposition”, and thus ensuring that she will pay all his bills at an hotel. Pancks takes it to the Clennam house, and as they wait for an answer:

“He smoked his cigarette out, with his ugly smile so fixed upon his face that he looked as though he were smoking with his drooping beak of a nose, rather than with his mouth; like a fancy in a weird picture.”

Blandois begins to talk of “Della bella Gowana, sir, as they say in Italy. Of the Gowan, the fair Gowan.” (Minnie/Pet) and also of Miss Wade. He boasts how Miss Wade paid him to find out what he can of the Gowans, to “know the manner of their life, how the fair Gowana is beloved, how the fair Gowana is cherished, and so on.” He indulged her her curiosity, graciously, he says, and goes on to comment more.

“it was not well of the fair Gowana to make mysteries of letters from old lovers, in her bedchamber on the mountain, that her husband might not see them. No, no. That was not well.”

At last Pancks returns with Flintwinch, who has been sent by Mrs. Clennam to represent her. He has a note for Arthur:

“I hope it is enough that you have ruined yourself. Rest contented without more ruin. Jeremiah Flintwinch is my messenger and representative. Your affectionate M. C.”

When Flintwinch can get away from Blandois’ ridiculously excessive embraces, he tells him that Mrs. Clennam agrees to his request, and they all leave.

The chapter ends with Arthur Clennam:

“The prisoner, with the feeling that he was more despised, more scorned and repudiated, more helpless, altogether more miserable and fallen than before, was left alone again.”

A long, busy chapter, in which many characters we know meet together, really moving towards tying up all the threads.

Arthur has been in the Marshalsea for a while, but has not socialised very much:

“Imprisonment began to tell upon him. He knew that he idled and moped … Anybody might see that the shadow of the wall was dark upon him.”

When he has been there for almost three months, he is much surprised by a visit from the sprightly young Barnacle, Ferdinand:

'It was the Sprightly Young Barnacle' - James Mahoney

Ferdinand Barnacle is keen to say that he hopes “our place”, (the Circumlocution Office) has nothing to do with Arthur’s imprisonment, and is pleased when Arthur assures him they have not. Once again the engaging chap tries to explain the Circumlocution Office’s function:

“You’ll say we are a humbug. I won’t say we are not; but all that sort of thing is intended to be, and must be. Don’t you see?’ … we only ask you to leave us alone, and we are as capital a Department as you’ll find anywhere.”

But despite several attempts to express this thought in different ways, and that “Everybody is ready to dislike and ridicule any invention”, he cannot get Arthur to agree. He asks whether it is due to Mr. Merdle that Arthur has been imprisoned:

“‘He must have been an exceedingly clever fellow … A consummate rascal, of course, …but remarkably clever! One cannot help admiring the fellow. Must have been such a master of humbug. Knew people so well-got over them so completely-did so much with them!’…

In his easy way, he was really moved to genuine admiration.“

And breezy, light-hearted and charming as ever, the engaging young Barnacle goes off to mount his horse, and rides off to his next appointment.

Arthur’s next visitor is Mr. Rugg who urges Arthur to move to the “Kings Bench Prison”, as it would be much more fitting to a man in his position. He says that even his daughter, as the plaintiff in Rugg and Bawkins, had expressed her surprise at hearing he was there. After attempting to change his mind by persuasion and then sarcasm, and still finding Arthur unmoved on the subject, he takes his leave, offended and in high dudgeon, and showing in a “military man” on the way out.

Who should this be, but Blandois! And Blandois in a company we have not seen before: Cavalletto and Pancks. Arthur had thought he recognised the sound of the “display of stride and clatter meant to be insulting” and watches as Cavelletto takes up a seated guarding position by the door, and Pancks stares out of the window.

'In the Old Room' - Phiz

There follows a long conversation, with Blandois at his most “impudent and wicked”, swaggering and crafty. Eventually we get to the nub:

“‘I want to know,’ returned Arthur, without disguising his abhorrence, ‘how you dare direct a suspicion of murder against my mother’s house? … I want that suspicion to be cleared away … I want to know, moreover, what business you had there when I had a burning desire to fling you down-stairs … I have seen enough of you to know that you are a bully and coward.’”

But after all Blandois’ insolence and bluster, we and Arthur are no nearer to solving the mystery, or as Blandois terms it the “game”.

We know that Blandois claims to have a commodity to sell Arthur’s mother, and that because she vexed him, and did not immediately accept this, he had decided to disappear for a while. He says that Arthur’s mother and Flintwinch would have been pleased enough to make sure of this themselves. Exceedingly pleased with the worry that his disappearance caused, he stayed away, until Cavalletto had discovered him on Arthur’s behalf, disguised as an old soldier. Perhaps, Blandois suggests “with his horrible smile”, it would have been better to leave him alone? But Arthur says he wants his two friends to keep an eye on Blandois, until he can be brought to justice.

This annoys Blandois, who says “You have interrupted my little project” but lets it pass. “After some villainous thinking and smiling”, he writes an arrogant and outrageous letter to Mrs. Clennam, referring to their “little proposition”, and thus ensuring that she will pay all his bills at an hotel. Pancks takes it to the Clennam house, and as they wait for an answer:

“He smoked his cigarette out, with his ugly smile so fixed upon his face that he looked as though he were smoking with his drooping beak of a nose, rather than with his mouth; like a fancy in a weird picture.”

Blandois begins to talk of “Della bella Gowana, sir, as they say in Italy. Of the Gowan, the fair Gowan.” (Minnie/Pet) and also of Miss Wade. He boasts how Miss Wade paid him to find out what he can of the Gowans, to “know the manner of their life, how the fair Gowana is beloved, how the fair Gowana is cherished, and so on.” He indulged her her curiosity, graciously, he says, and goes on to comment more.

“it was not well of the fair Gowana to make mysteries of letters from old lovers, in her bedchamber on the mountain, that her husband might not see them. No, no. That was not well.”

At last Pancks returns with Flintwinch, who has been sent by Mrs. Clennam to represent her. He has a note for Arthur:

“I hope it is enough that you have ruined yourself. Rest contented without more ruin. Jeremiah Flintwinch is my messenger and representative. Your affectionate M. C.”

When Flintwinch can get away from Blandois’ ridiculously excessive embraces, he tells him that Mrs. Clennam agrees to his request, and they all leave.

The chapter ends with Arthur Clennam:

“The prisoner, with the feeling that he was more despised, more scorned and repudiated, more helpless, altogether more miserable and fallen than before, was left alone again.”

message 74:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 12:12PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

After Ferdinand Barnacle’s explanation on how government departments function on the basis of inaction, he assures Arthur that he “know[s] the way out (of the Marshalsea) perfectly.”

I think there is a deliberate double meaning here. The Circumlocution Office symbolically imprisons all innovation, creativity and progress while, at the same time, freeing up all the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings to expand their presence and value to society.

Barnacles grow beneath a ship, thus impeding the ship’s progress. Of course these government Barnacles can move in and out of their office or a prison smoothly; but those whom the Barnacles’ offices and rules are meant to serve, become weighted down and imprisoned by their presence.

Although Ferdinand Barnacle is put in Little Dorrit for comic relief, the message Charles Dickens gives through him is a bleak one. Take this excerpt, where Arthur is optimistic, but has his hopes quashed:

“‘I hope,’ said Arthur, ‘that he and his dupes may be a warning to people not to have so much done with them again.’

‘My dear Mr Clennam,’ returned Ferdinand, laughing, ‘have you really such a verdant hope? The next man who has as large a capacity and as genuine a taste for swindling, will succeed as well. Pardon me, but I think you really have no idea how the human bees will swarm to the beating of any old tin kettle; in that fact lies the complete manual of governing them. When they can be got to believe that the kettle is made of the precious metals, in that fact lies the whole power of men like our late lamented. No doubt there are here and there,’ said Ferdinand politely, ’exceptional cases, where people have been taken in for what appeared to them to be much better reasons; and I need not go far to find such a case; but they don’t invalidate the rule.“

Charles Dickens is telling us through this engaging Barnacle, that greed, fraud, adulation and idolatry will continue to wreck lives, and reap a grim harvest of death. And from the number of names of Americans (who I don’t know, but every country has their own!) mentioned as perpetrating similar frauds to Mr. Merdle’s, this syndrome is alive and kicking to this day.

Charles Dickens, sadly, was right.

I think there is a deliberate double meaning here. The Circumlocution Office symbolically imprisons all innovation, creativity and progress while, at the same time, freeing up all the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings to expand their presence and value to society.

Barnacles grow beneath a ship, thus impeding the ship’s progress. Of course these government Barnacles can move in and out of their office or a prison smoothly; but those whom the Barnacles’ offices and rules are meant to serve, become weighted down and imprisoned by their presence.

Although Ferdinand Barnacle is put in Little Dorrit for comic relief, the message Charles Dickens gives through him is a bleak one. Take this excerpt, where Arthur is optimistic, but has his hopes quashed:

“‘I hope,’ said Arthur, ‘that he and his dupes may be a warning to people not to have so much done with them again.’

‘My dear Mr Clennam,’ returned Ferdinand, laughing, ‘have you really such a verdant hope? The next man who has as large a capacity and as genuine a taste for swindling, will succeed as well. Pardon me, but I think you really have no idea how the human bees will swarm to the beating of any old tin kettle; in that fact lies the complete manual of governing them. When they can be got to believe that the kettle is made of the precious metals, in that fact lies the whole power of men like our late lamented. No doubt there are here and there,’ said Ferdinand politely, ’exceptional cases, where people have been taken in for what appeared to them to be much better reasons; and I need not go far to find such a case; but they don’t invalidate the rule.“

Charles Dickens is telling us through this engaging Barnacle, that greed, fraud, adulation and idolatry will continue to wreck lives, and reap a grim harvest of death. And from the number of names of Americans (who I don’t know, but every country has their own!) mentioned as perpetrating similar frauds to Mr. Merdle’s, this syndrome is alive and kicking to this day.

Charles Dickens, sadly, was right.

So now we know Miss. Wade paid Blandois to spy on the Gowans. Jeepers, seems like Miss. Wade had a fatal attraction thing going on there.

So now we know Miss. Wade paid Blandois to spy on the Gowans. Jeepers, seems like Miss. Wade had a fatal attraction thing going on there. Arthur's mother is awful. Good gosh, she treated Amy Dorrit better than she is treating her own son!

Jean, yes, sadly, Charles Dickens was right.

Yes, quite unfortunate but Mr. Dickens was quite right. People will fall for the next charming con-man who promises them quick fortune, just as quickly as they fell for the first one.

Yes, quite unfortunate but Mr. Dickens was quite right. People will fall for the next charming con-man who promises them quick fortune, just as quickly as they fell for the first one. Poor Arthur. The note from his mother made me want to knock her out of her wheelchair. What a cruel and unfeeling woman!

You and I have been marking many of the same passages, Jean, which encourages me to think I am not missing anything significant as I go.

That Miss Wade paid Blandois to spy on the Gowans makes me wonder what evil she has up her sleeve. No need to spy on them unless she is planning to use the information.

Jean,

Jean,Good summary of a complicated chapter. Thanks

Yes, we here in the US currently have a consummate swindler here with a lot of gullible followers - but I will refrain from that.

I think we may know now how people got worked up about Blandois which has never made sense to me.

Remember the notice or whatever it was called that everyone was reading? I could not figure out who would possibly care what happened to this foreign, disagreeable Blandois character in a big town like London. Or even how anyone would surmise that he was last seen at the Clennam's at night, so why the suspicion that Arthur was concerned about?

Well, I think when Blandois decided to play his game and harm the Clennams he printed up a few notices himself and posted them. Remember that he forged a letter of introduction about credit that he showed to Arthur's mother. (I always assumed it was forged anyway.) So he printed up some sheets saying if anyone knows of the whereabouts of Blandois - last seen the night of X, at the Clennam residence, contact the police (or something to that effect). He himself wanted to hurt them so he printed up these things. Just like I assume he forged this letter of introduction.

This part confused me:

This part confused me:"“it was not well of the fair Gowana to make mysteries of letters from old lovers, in her bedchamber on the mountain, that her husband might not see them. No, no. That was not well.”

Did I miss something? From what we've read so far she had no old lovers or did I miss something? Are these letters real? Did Blandois fabricate these letters?

Anne, I think the letter Blandios was referring to was the letter Arthur gave Amy to give to Minnie, that she then gave back to Amy. Blandios is being his usual overbearing self here!

Anne, I think the letter Blandios was referring to was the letter Arthur gave Amy to give to Minnie, that she then gave back to Amy. Blandios is being his usual overbearing self here!

Jenny wrote: "Anne, I think the letter Blandios was referring to was the letter Arthur gave Amy to give to Minnie, that she then gave back to Amy. Blandios is being his usual overbearing self here!"

Jenny wrote: "Anne, I think the letter Blandios was referring to was the letter Arthur gave Amy to give to Minnie, that she then gave back to Amy. Blandios is being his usual overbearing self here!"I remember that. But there were no "letters in her bedchamber," right? He's just making it up?

Anne - "This part confused me:

"“it was not well of the fair Gowana to make mysteries of letters from old lovers..."

Another teaser, I think! I don't think this has been referred to before. Of course it could be more of Blandois' bluster and lies.

My personal theory is that Blandois is fishing for information here. He is trying to make Arthur think he has more shady evidence that he actually has. He probably knows that Arthur was sweet on Minnie. Blandois lived with the Gowans for some time, so Henry or Minnie probably let it slip. Even a meaningful glance would be enough for someone like Blandois to pick up and mentally file away for the future. So he may well be goading Arthur, whiling way the time by trying to find out something else he can uses for his devious plans. But we suspect there will be no letters from Arthur as he is too honourable, and "had decided not to fall in love with Pet."

But that's just my theory :)

"“it was not well of the fair Gowana to make mysteries of letters from old lovers..."

Another teaser, I think! I don't think this has been referred to before. Of course it could be more of Blandois' bluster and lies.

My personal theory is that Blandois is fishing for information here. He is trying to make Arthur think he has more shady evidence that he actually has. He probably knows that Arthur was sweet on Minnie. Blandois lived with the Gowans for some time, so Henry or Minnie probably let it slip. Even a meaningful glance would be enough for someone like Blandois to pick up and mentally file away for the future. So he may well be goading Arthur, whiling way the time by trying to find out something else he can uses for his devious plans. But we suspect there will be no letters from Arthur as he is too honourable, and "had decided not to fall in love with Pet."

But that's just my theory :)

Sara - "You and I have been marking many of the same passages, Jean, which encourages me to think I am not missing anything significant as I go."

That's very reassuring to me too - and for the same reason!

That's very reassuring to me too - and for the same reason!

message 83:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 12:58PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark - "Jean, Good summary of a complicated chapter. Thanks"

Thank you Mark! I'm glad they are useful :)

About your theory "Remember that he forged a letter of introduction about credit that he showed to Arthur's mother. (I always assumed it was forged anyway.)"

Yes, I think it's quite within Blandois' character to forge a letter - or at least to know and pay someone who could forge it for him. He had recently been in prison in Marseilles after all! But I'm not so sure this bit works:

"Well, I think when Blandois decided to play his game and harm the Clennams he printed up a few notices himself and posted them."

Blandois could have done this ... but why in that case would Mrs. Clennam fallen in with his demand to see her? He can no longer hold over her the suspicion that Mrs. Clennam has arranged for his murder, as Arthur so indignantly referred to, now that he has been found. We have 3 people in this very room who have seen him, and presumably there are more.

Blandois does seem to be calling the shots. Although he's been "taken in custody" by Pancks and Cavalletto, (prior to Arthur alerting the proper authorities) he still seems able to order the time for an appointment with Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch, and refer to his “little proposition”.

If at the end of this chapter, we were still awaiting an answer from Mrs. Clennam, we could believe that Blandois had fabricated the entire thing - and printed wanted notices as you say. But she has replied, in a way designed to hurt and reject Arthur even more. The only interpretation I can put on this is that she has to accede to Blandois' request for some reason, but does not want to lose face, so she uses it as another excuse to denigrate Arthur.

Blandois smiles when he learns her reply. This means that he is pleased that he will see Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch, and be able to do whatever twisted thing he plans - and have his hotel bill paid into the bargain!

Thank you Mark! I'm glad they are useful :)

About your theory "Remember that he forged a letter of introduction about credit that he showed to Arthur's mother. (I always assumed it was forged anyway.)"

Yes, I think it's quite within Blandois' character to forge a letter - or at least to know and pay someone who could forge it for him. He had recently been in prison in Marseilles after all! But I'm not so sure this bit works:

"Well, I think when Blandois decided to play his game and harm the Clennams he printed up a few notices himself and posted them."

Blandois could have done this ... but why in that case would Mrs. Clennam fallen in with his demand to see her? He can no longer hold over her the suspicion that Mrs. Clennam has arranged for his murder, as Arthur so indignantly referred to, now that he has been found. We have 3 people in this very room who have seen him, and presumably there are more.

Blandois does seem to be calling the shots. Although he's been "taken in custody" by Pancks and Cavalletto, (prior to Arthur alerting the proper authorities) he still seems able to order the time for an appointment with Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch, and refer to his “little proposition”.

If at the end of this chapter, we were still awaiting an answer from Mrs. Clennam, we could believe that Blandois had fabricated the entire thing - and printed wanted notices as you say. But she has replied, in a way designed to hurt and reject Arthur even more. The only interpretation I can put on this is that she has to accede to Blandois' request for some reason, but does not want to lose face, so she uses it as another excuse to denigrate Arthur.

Blandois smiles when he learns her reply. This means that he is pleased that he will see Mrs. Clennam and Flintwinch, and be able to do whatever twisted thing he plans - and have his hotel bill paid into the bargain!

message 84:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 12:55PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Jenny - "Anne, I think the letter Blandios was referring to was the letter Arthur gave Amy to give to Minnie, that she then gave back to Amy!"

At first I thought he could not know this, but thinking back to the inn at the beginning of Book 2, Blandois was snooping quite a bit. It's quite possible that he knew Amy had a letter for Minnie, and who it was from (Arthur), if he was eavesdropping. As you pointed out though, Minnie gave it straight back. So yes, he's just blustering, and yes Anne there are no letters. He's just fishing :)

At first I thought he could not know this, but thinking back to the inn at the beginning of Book 2, Blandois was snooping quite a bit. It's quite possible that he knew Amy had a letter for Minnie, and who it was from (Arthur), if he was eavesdropping. As you pointed out though, Minnie gave it straight back. So yes, he's just blustering, and yes Anne there are no letters. He's just fishing :)

If I remember correctly, Anne and Jean, Amy did bring the letter to Minnie in her bedchamber at the inn... Blandios, though a bad man, is rather intriguing. I also find it interesting how twisted Mr. Flintwich does not like him, even though they are both bad men!

If I remember correctly, Anne and Jean, Amy did bring the letter to Minnie in her bedchamber at the inn... Blandios, though a bad man, is rather intriguing. I also find it interesting how twisted Mr. Flintwich does not like him, even though they are both bad men!

message 86:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 20, 2020 03:33PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Jenny wrote: "Amy did bring the letter to Minnie in her bedchamber at the inn..."

She did, yes. Minnie had gone upstairs as she was tired and felt ill. Fanny sent her maid to help, but Amy went on her own account, to give her the letter, although the others will not have known that.

It was whether Blandois could have known about the letter, that gave me pause for thought.

She did, yes. Minnie had gone upstairs as she was tired and felt ill. Fanny sent her maid to help, but Amy went on her own account, to give her the letter, although the others will not have known that.

It was whether Blandois could have known about the letter, that gave me pause for thought.

Thank you Jean and Jenny for working so hard on my question about Blandois and the letter. I'd forgotten that the letter was given to her at the inn. But still, it wasn't a matter of "letters under her bed."

Thank you Jean and Jenny for working so hard on my question about Blandois and the letter. I'd forgotten that the letter was given to her at the inn. But still, it wasn't a matter of "letters under her bed."

I'd like to quote from the "Cassandra" of this tale, chapter II -

I'd like to quote from the "Cassandra" of this tale, chapter II -"We shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and many strange roads...and what it is set to us to do to them, and what it is set to them to do to us, will all be done... You may be sure that there are men and women already on their road, who have their business to do with you, and who will do it. Of a certainty they will do it. They may be coming hundreds, thousands, of miles over the sea there; they may be close at hand now; they may be coming, for anything you know or anything you can do to prevent it, from the vilest sweepings of this very town."

That has certainly been true of all of the characters in this story. So many of them acting upon one another for good or ill, almost like pinballs knocking each other, causing more to careen off into others. Even Arthur who travelled from China to London and met Amy...thanks to his mother hiring her.

In the passage where Arthur realizes that Amy is his life's "vanishing point," it continues...

"He had traveled thousands of miles towards it." (Amy as the center of his life's perspective).

Also Pancks' investigations giving the Dorrits their freedom; Young John's intrusion on Mr Dorrit leading to his breakdown; Rigaud's effects and schemes on everyone, including Miss Wade, Gowan, and even the Gowans' dog; the Circumlocution Office's wasteful effects on Doyce and Clennam and countless others; Merdle's ruinous effects on hundreds; Arthur's effects on Amy and vice versa; Miss Wade "rescuing" Tattycoram; Mrs Clennam and Amy; Mrs Clennam and God knows what; and many more.

No matter what you think of her, Miss Wade is right.

Sara wrote: "Yes, quite unfortunate but Mr. Dickens was quite right. People will fall for the next charming con-man who promises them quick fortune, just as quickly as they fell for the first one.

Sara wrote: "Yes, quite unfortunate but Mr. Dickens was quite right. People will fall for the next charming con-man who promises them quick fortune, just as quickly as they fell for the first one. Poor Arthur..."

Miss Wade, once again, is bent on making herself miserable by obsessing about Minnie instead of getting on with her life.

I am curious about the instructions that Arthur gave Mr. Pancks at the end of the chapter. I'm also wondering why he was so quick to let Cavalletto go with Blandois. Maybe Arthur has some plans of his own.

I am curious about the instructions that Arthur gave Mr. Pancks at the end of the chapter. I'm also wondering why he was so quick to let Cavalletto go with Blandois. Maybe Arthur has some plans of his own.

Mark wrote: "I'd like to quote from the "Cassandra" of this tale, chapter II -

Mark wrote: "I'd like to quote from the "Cassandra" of this tale, chapter II -"We shall meet the people who are coming to meet us, from many strange places and many strange roads...and what it is set to us to..."

I love that passage, Mark, and you are so right in your observations. "No man is an island" we all affect the lives of others, and even have effects on them that we, ourselves, might never comprehend. I am not sure if Dickens believed in fate or destiny, but his characters certainly should. Arthur does travel the world to find Amy right at home (I use that word loosely, considering what Arthur's "home" is like). Their fates are linked from the beginning.

I love your description of the characters as pinballs. It seems they are exactly that, always bumping into one another and unable to avoid contact even from those they would wish to (thinking Blandois and Cavalletto, or really Blandois and anyone). If you think of your own life, you might find that is true for you, as well. It is one of Dickens' strengths. He creates a lot of coincidences in his novels, but he makes them feel so natural and reflective of real life that you seldom even notice them.

Katy wrote: "I am curious about the instructions that Arthur gave Mr. Pancks at the end of the chapter. I'm also wondering why he was so quick to let Cavalletto go with Blandois. Maybe Arthur has some plans of ..."

Katy wrote: "I am curious about the instructions that Arthur gave Mr. Pancks at the end of the chapter. I'm also wondering why he was so quick to let Cavalletto go with Blandois. Maybe Arthur has some plans of ..."Not sure if Arthur really has plans regarding Bandois, but I think he knows it is better to have someone watching him than to lose him again. Better the evil you can see developing...how hard is it on Arthur to know this man is out there working his evil and Arthur is unable to leave his cell to have any chance of stopping him.

Sara, it seemed to me that Mrs. Clennam is being extorted for money which she initially did not want to pay which is why Blandois left, getting everyone worried. But now, out of fear, I assume, she is willing to pay the amount Bladois asked which is why he can afford a nice hotel.

Sara, it seemed to me that Mrs. Clennam is being extorted for money which she initially did not want to pay which is why Blandois left, getting everyone worried. But now, out of fear, I assume, she is willing to pay the amount Bladois asked which is why he can afford a nice hotel.

I enjoyed the backward, absurd logic of Ferninand Barnacle. He is so sure that the Circumlocution Office is doing its part in society. It's comical but also illogically logical.

I enjoyed the backward, absurd logic of Ferninand Barnacle. He is so sure that the Circumlocution Office is doing its part in society. It's comical but also illogically logical. Tried to remember who does that absurd logic best -- it is mostly modern in spirit, isn't it? Are there many Victorian authors doing this?

I thought of Alice in Wonderland's Red Queen. But I think it is closest to the absurd logic of Waiting for Godot.

Re authors that were able to be illogically logical with biting satire, I forgot Jonathan Swift. He's much earlier than Dickens but definitely honed his illogic to a great degree.

Re authors that were able to be illogically logical with biting satire, I forgot Jonathan Swift. He's much earlier than Dickens but definitely honed his illogic to a great degree.

message 97:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 21, 2020 09:09AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Mark - I can't put my response to your post about "the Cassandra" of this tale (i.e. Miss Wade), and the pinball effect, any better than Sara did :)

Perhaps we need to have a discussion about absurd logic and satire in a few days - when we have completed the book?

A note here that I've added three more illustrations to chapter 27. (Nisa's links at the beginning of the thread are invaluable when searching for an summary :) ) These images had been hiding from me! As usual, I especially like the one by Harry Furniss.

And now for the last chapter in installment 8. Tomorrow begins the penultimate installment in the novel :)

Perhaps we need to have a discussion about absurd logic and satire in a few days - when we have completed the book?

A note here that I've added three more illustrations to chapter 27. (Nisa's links at the beginning of the thread are invaluable when searching for an summary :) ) These images had been hiding from me! As usual, I especially like the one by Harry Furniss.

And now for the last chapter in installment 8. Tomorrow begins the penultimate installment in the novel :)

message 98:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 21, 2020 09:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 29:

Imprisoned in the Marshalsea, Arthur Clennam’s spirits becomes increasingly low. Night after night he gets out of his “bed of wretchedness” at twelve or one o’clock, and watches for the sunrise. But today he cannot even undress. He feels that he can barely breathe; that he is suffocating. The narrator comments that other prisoners had also felt this, and it lasted for a couple of days, before leaving Arthur with a slow fever.

Arthur wants to be alone in his illness and misery. He tells Mrs. Plornish by letter not to visit, because he is occupied with his affairs, and makes sure that whenever Young John calls in to see if he needs anything, Arthur pretends to be busy writing, and answers cheerfully that he does not. They never mention the heart-to-heart they had had, or who they had talked about, but she is always in Arthur’s thoughts.

“The sixth day of the appointed week was a moist, hot, misty day. It seemed as though the prison’s poverty, and shabbiness, and dirt, were growing in the sultry atmosphere. With an aching head and a weary heart, Clennam had watched the miserable night out, listening to the fall of rain on the yard pavement, thinking of its softer fall upon the country earth. A blurred circle of yellow haze had risen up in the sky in lieu of sun, and he had watched the patch it put upon his wall, like a bit of the prison’s raggedness.”

Arthur feels so ill and faint, that he even has to rest a few times, while he is getting dressed. Because he has not slept or eaten for so many days, his mind begins to wander, and he becomes slightly delirious. He dozes and hears voices, waking with a start as he realises that it is he who is speaking, and has, in his dreamlike state:

“some abiding impression of a garden stole over him—a garden of flowers, with a damp warm wind gently stirring their scents”.

It is such a painful effort to lift his head, that it is a whole before he realises what this is. Next to him, he can see a wonderful little bunch of the most lovely flowers. Arthur is filled with delight; nothing has ever seen so beautiful to him, but eventually he lapses back to his weakened state.

In the doorway, he seems to see his Little Dorrit in her old, worn dress. Can this be? He cries out, and sees, “in the loving, pitying, sorrowing, dear face, as in a mirror, how changed he was”.

She comes towards him, “So faithful, tender, and unspoiled by Fortune … so Angelically comforting and true!”

Maggy is there too, chuckling.

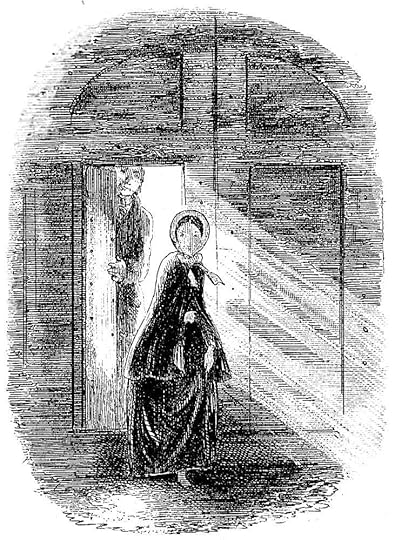

Little Dorrit and Maggy visiting Arthur Clennam in the Marshalsea - James Mahoney

Little Dorrit hopes he has thought of her, and the joy in her face when he says he has, fills him with shame.

“She looked something more womanly than when she had gone away, and the ripening touch of the Italian sun was visible upon her face. But, otherwise, she was quite unchanged. The same deep, timid earnestness that he had always seen in her, and never without emotion, he saw still. If it had a new meaning that smote him to the heart, the change was in his perception, not in her.”

Little Dorrit sets to work, making the room straight and fresh and sending Maggy out for choice foods to tempt her patient. Then she starts to make Arthur a curtain for his window.

“And how dearly he loved her now, what words can tell!

As they sat side by side in the shadow of the wall, the shadow fell like light upon him.“

It is nearly time for Little Dorrit to go, but she has something she must tell her friend, Mr. Clennam. Her brother has come home to deal with their father’s affairs. He will go back abroad, but she will not. He is very grateful to her now, because she nursed him through his illness, “much too grateful, for it is only because I happened to be with him” and he wants her to be happy:

“He says, if there is a will, he is sure I shall be left rich; and if there is none, that he will make me so.”

Little Dorrit is determined to go on. She has no use for this money, and begs Mr. Clennam to let her lend—or give—it to him:

“you will give me the greatest joy I can experience on earth, the joy of knowing that I have been serviceable to you, and that I have paid some little of the great debt of my affection and gratitude.”

Arthur cannot accept, and gently says:

“No, darling Little Dorrit. No, my child. I must not hear of such a sacrifice.”

And he goes on to tell her what he has learned about himself:

“If, in the bygone days … I had understood myself … better, and had read the secrets of my own breast more distinctly;… and told you that I loved and honoured you, not as the poor child I used to call you, but as a woman whose true hand would raise me high above myself and make me a far happier and better man … and if something had kept us apart then, when I was moderately thriving, and when you were poor; I might have met your noble offer of your fortune, dearest girl, with other words than these, and still have blushed to touch it. But, as it is, I must never touch it, never!”

It would make him ashamed; he is disgraced enough. He is old, rougher, and ruined, and no earnest pleas from Little Dorrit can change his mind.

The bell rings and Arthur has another request. She must not come to see him soon, or often. The Marshalsea is no place for her. Maggy cannot contain herself any longer, and says he must go to hospital, and remembering Little Dorrit’s story:

“And then the little woman as was always a spinning at her wheel, she can go to the cupboard with the Princess, and say, what do you keep the Chicking there for? and then they can take it out and give it to him, and then all be happy!”

Arthur uses the last of his strength to take them downstairs, until the gate closes with a “funeral clang that … sounded into Arthur’s heart”.

'Little Dorrit Leaving the Marshalsea' - Phiz

Much later, nearly midnight, Young John tiptoes into Arthur’s room in his stockinged feet—even though it is against all the rules. He thought Mr. Clennam would want to make sure that Miss Dorrit got home safely. And did Mr. Clennam know what she talked of all the way? Mr Clennam did not. Why, him. And she sent him a message:

‘“that his Little Dorrit sent him her undying love.” Now it’s delivered. Have I been honourable, sir?’”

Young John’s voice quavers, and Mr. Clennam assures him that he has, very:

“‘There’s my hand, sir,’ said John, ‘and I’ll stand by you forever!’”

Imprisoned in the Marshalsea, Arthur Clennam’s spirits becomes increasingly low. Night after night he gets out of his “bed of wretchedness” at twelve or one o’clock, and watches for the sunrise. But today he cannot even undress. He feels that he can barely breathe; that he is suffocating. The narrator comments that other prisoners had also felt this, and it lasted for a couple of days, before leaving Arthur with a slow fever.

Arthur wants to be alone in his illness and misery. He tells Mrs. Plornish by letter not to visit, because he is occupied with his affairs, and makes sure that whenever Young John calls in to see if he needs anything, Arthur pretends to be busy writing, and answers cheerfully that he does not. They never mention the heart-to-heart they had had, or who they had talked about, but she is always in Arthur’s thoughts.

“The sixth day of the appointed week was a moist, hot, misty day. It seemed as though the prison’s poverty, and shabbiness, and dirt, were growing in the sultry atmosphere. With an aching head and a weary heart, Clennam had watched the miserable night out, listening to the fall of rain on the yard pavement, thinking of its softer fall upon the country earth. A blurred circle of yellow haze had risen up in the sky in lieu of sun, and he had watched the patch it put upon his wall, like a bit of the prison’s raggedness.”