Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit II: Chapters 1 - 11

message 51:

by

Anne

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Oct 25, 2020 10:14AM

Mona, I completely agree with everything you wrote. The whole family ganging up on Amy because she acts as a "menial" when she nurses Mrs. Gowan, which by the way she was raised to do - alway caring for her father and everyone else. They have quickly forgotten how kind Arthur was to them. Well, Mr. Dorrit wants to forget that he required Arthur's kindness, as he says, he wants to put that all behind him. He's paranoid and anxious that anyone will know of their past or see them as beneath their current social/financial status. He treats the hotel manager so badly, but in doing so he asks "how am I different from others in my class" (paraphrasing) which shows how anxious he - as if the light were personal, when in fact, it had nothing to do with him. The last scene with Amy alone and lonely remembering her old friends and her old life was very poignant.

Mona, I completely agree with everything you wrote. The whole family ganging up on Amy because she acts as a "menial" when she nurses Mrs. Gowan, which by the way she was raised to do - alway caring for her father and everyone else. They have quickly forgotten how kind Arthur was to them. Well, Mr. Dorrit wants to forget that he required Arthur's kindness, as he says, he wants to put that all behind him. He's paranoid and anxious that anyone will know of their past or see them as beneath their current social/financial status. He treats the hotel manager so badly, but in doing so he asks "how am I different from others in my class" (paraphrasing) which shows how anxious he - as if the light were personal, when in fact, it had nothing to do with him. The last scene with Amy alone and lonely remembering her old friends and her old life was very poignant.

reply

|

flag

Debra, I agree completely. Amy's uncle is so sweet to her. They have the same kind nature and neither cares about society or money or how they are viewed.

Debra, I agree completely. Amy's uncle is so sweet to her. They have the same kind nature and neither cares about society or money or how they are viewed.

It would be nice if Amy and her uncle could go somewhere else and live. But I do not see that happening, Amy is so devoted to her father.

It would be nice if Amy and her uncle could go somewhere else and live. But I do not see that happening, Amy is so devoted to her father.

Right. I don't see that happening either, but what a nice fantasy, to see those two escape the rest of the Dorrits.

Right. I don't see that happening either, but what a nice fantasy, to see those two escape the rest of the Dorrits.

Yes, nice fantasy. Now I am wondering about the money. They are spending it like they have a gazillion dollars...and maybe they do. I am guessing Amy's father has complete control over the money.

Yes, nice fantasy. Now I am wondering about the money. They are spending it like they have a gazillion dollars...and maybe they do. I am guessing Amy's father has complete control over the money.

message 57:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 25, 2020 11:25AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Debra wrote: "I am wondering about the money. They are spending it like they have a gazillion dollars...and maybe they do. I am guessing Amy's father has complete control over the money."

That's a good point Debra! We haven't heard that he has any financial advice, yet his class would have an estate manager or an accountant at the very least!

That's a good point Debra! We haven't heard that he has any financial advice, yet his class would have an estate manager or an accountant at the very least!

Mr. Dorrit does have control over the money. He inherited the money/the estate. No hint yet as to overspending but one trip such as they are taking is probably affordable for them now. But who knows what will happen in the future? Why is Blandois hanging around them? I can see Edward getting into trouble gambling.

Mr. Dorrit does have control over the money. He inherited the money/the estate. No hint yet as to overspending but one trip such as they are taking is probably affordable for them now. But who knows what will happen in the future? Why is Blandois hanging around them? I can see Edward getting into trouble gambling.

As head of the family he would, yes Anne. But no upper-class gentleman would not delegate, or have professional advice on this.

Jean, yes. I understand. My point was that even with advisors the money can be spent, lost or stolen or lord knows what....

Jean, yes. I understand. My point was that even with advisors the money can be spent, lost or stolen or lord knows what....

Oh no. Now I can see Blandois as the Dorrit's financial advisor. Before, I kept thinking Blandois was going to try and and marry into the Dorrit family. But financial advisor would be a much better position for him. No pesky wife to kill off.

Oh no. Now I can see Blandois as the Dorrit's financial advisor. Before, I kept thinking Blandois was going to try and and marry into the Dorrit family. But financial advisor would be a much better position for him. No pesky wife to kill off.

Debra, the way they were arguing and posturing I don't see that Blandois is his financial advisor. I'd still like to know how he ended up in the Alps with them and if he is still around them or not. I imagine he's around....somewhere.

Debra, the way they were arguing and posturing I don't see that Blandois is his financial advisor. I'd still like to know how he ended up in the Alps with them and if he is still around them or not. I imagine he's around....somewhere.

The fact that Blandois is showing such interest in them seems to indicate that he is thinking of some way of parting them from their money. Amy distrusts him, but the others seem like they could easily be taken in.

The fact that Blandois is showing such interest in them seems to indicate that he is thinking of some way of parting them from their money. Amy distrusts him, but the others seem like they could easily be taken in.Like someone else here mentioned, I am also wondering what Maggy is doing. But I'm sure we'll find out.

message 65:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 25, 2020 11:31AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Debra wrote: "Oh no. Now I can see Blandois as the Dorrit's financial advisor ..."

Do you mean he is jostling for position to become this? That's certainly a possibility, and could be why he is observing them all so closely. We've seen he's quite a confidence trickster.

I can see where you're coming from too, Katy :)

Amy seems to have good instincts.

Do you mean he is jostling for position to become this? That's certainly a possibility, and could be why he is observing them all so closely. We've seen he's quite a confidence trickster.

I can see where you're coming from too, Katy :)

Amy seems to have good instincts.

Jean, yes, he is jostling for position to become financial advisor. Somehow he will try to get the Dorrit's money.

Jean, yes, he is jostling for position to become financial advisor. Somehow he will try to get the Dorrit's money.I am so worried about Maggie. I keep looking for her.

I think it is psychologically accurate that sometimes people resent those who have been good to them, the way Mr. Dorrit now resents Arthur. It is a reminder that he needed help once. Probably he doesn't want to see anyone from his former life either. Fanny is happy to show off her new status to Mrs. Merdle, but I don't think the Merdles knew about the prison, just that Fanny was a social inferior and gold digger.

I think it is psychologically accurate that sometimes people resent those who have been good to them, the way Mr. Dorrit now resents Arthur. It is a reminder that he needed help once. Probably he doesn't want to see anyone from his former life either. Fanny is happy to show off her new status to Mrs. Merdle, but I don't think the Merdles knew about the prison, just that Fanny was a social inferior and gold digger.

I think Fanny could handle the money, lifestyle, and burying the past better than any of the rest of the family.

I think Fanny could handle the money, lifestyle, and burying the past better than any of the rest of the family.

message 69:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 25, 2020 12:17PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin P wrote: "I think it is psychologically accurate that sometimes people resent those who have been good to them, the way Mr. Dorrit now resents Arthur ..."

Yes, I agree. You'll remember Mr. Dorrit also snubbed Mr. Rugg, at the end of Book 1, and he and Pancks had done all the work!

Mr. Dorrit is fully conscious of what he is doing, although I think Tip can't see further than Arthur not being willing to lend him any money.

Yes, the Merdles never knew about them living in the Marshalsea. It was a great secret from everyone, which is now the reason why Mr. Dorrit will not admit knowing anyone from those times. The only person who might have suspected is Amy's employer, Mrs. Clennam, but if you remember, she was very firm that she didn't want to be told. There might be various reasons for this.

Flora probably knows, as Amy has shared her story with her, but she is nice and doesn't count :)

Yes, I agree. You'll remember Mr. Dorrit also snubbed Mr. Rugg, at the end of Book 1, and he and Pancks had done all the work!

Mr. Dorrit is fully conscious of what he is doing, although I think Tip can't see further than Arthur not being willing to lend him any money.

Yes, the Merdles never knew about them living in the Marshalsea. It was a great secret from everyone, which is now the reason why Mr. Dorrit will not admit knowing anyone from those times. The only person who might have suspected is Amy's employer, Mrs. Clennam, but if you remember, she was very firm that she didn't want to be told. There might be various reasons for this.

Flora probably knows, as Amy has shared her story with her, but she is nice and doesn't count :)

This is a very insightful chapter. I felt for Minnie, left behind with only Gowan and Blandois to care for her...which means left on her own.

This is a very insightful chapter. I felt for Minnie, left behind with only Gowan and Blandois to care for her...which means left on her own. I felt a great surge of respect and kindness toward Uncle Frederick. He is unable to enjoy the new found riches, and only does as he is told, but his soul still recognizes the quality in Amy. I find it hard to express how much I despise the other Dorrits, ungrateful asses that they are. Arthur gives them help when they are in, and then gets them out of prison, something they could never have done alone, and they disparage him so. A curse upon them all. I would enjoy watching them lose their newfound fortune to the likes of some slick operator like Blandois...who has his eyes on them.

And, poor Amy. I knew she would be ill-suited for this life. It is a life without purpose. It was sad to read that she could escape from the attendance of that oppressive maid, who was her mistress, and a very hard one.... The others have been freed from prison, but Amy has been put into one. She had a freedom of spirit at the Marshalsea. She took care of others, but that was her choice; in this life, she has no choices at all.

Sara wrote: "The others have been freed from prison, but Amy has been put into one ..."

Nice :) Though I do think all three self-seeking Dorrits are slowly edging their ways toward their own unique prisons. We see signs.

Great observations, Sara :)

Nice :) Though I do think all three self-seeking Dorrits are slowly edging their ways toward their own unique prisons. We see signs.

Great observations, Sara :)

I agree, Jean, and then as we have observed all along, there are physical prisons and mental/spiritual ones, and Dorrit and company will never be able to escape the prisons of their own making.

I agree, Jean, and then as we have observed all along, there are physical prisons and mental/spiritual ones, and Dorrit and company will never be able to escape the prisons of their own making.

Sara wrote: "This is a very insightful chapter. I felt for Minnie, left behind with only Gowan and Blandois to care for her...which means left on her own.

Sara wrote: "This is a very insightful chapter. I felt for Minnie, left behind with only Gowan and Blandois to care for her...which means left on her own. I felt a great surge of respect and kindness toward U..."

If they do lose their newfound fortune to Blandois I think Amy will handle being poor again better than the rest of her family.

Katy - yes, it's a good job there is someone sensible and practical amongst this hopeless bunch!

message 75:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 26, 2020 03:55AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 4:

This short chapter is devoted to a letter from Little Dorrit to Arthur Clennam.

'Little Dorrit' in the 1987 BBC miniseries, (Sarah Pickering)

Little Dorrit makes it clear than she does not expect Mr. Clennam will have thought of her at all, but says that she will always remember his kindness to her, when she had no other friends. And then she goes on to clarify that she does not have any friends now either. However, she says, the purpose of her letter is to tell him that she has met Mrs. Gowan and that the young lady says she is “‘very well and very happy.’ And she looked most beautiful … who could help loving so beautiful and winning a creature!”

However, Amy has reservations about Mrs. Gowan’s husband:

“she is very fond of him, but I thought he was not earnest enough—I don’t mean in that respect—I mean in anything…. if I was Mrs Gowan (what a change that would be, and how I must alter to become like her!) I should feel that I was rather lonely and lost, for the want of some one who was steadfast and firm in purpose.”

Amy talks very poignantly about her old life, and how she misses it. We learn that the Plornishes’ business “which my dear father bought for them” is flourishing and that Mr. Nandy is now able to live with his family, and she hopes they are all happy. Amy is worried about Maggy:

“Will you go and tell her, as a strict secret, with my love, that she never can have regretted our separation more than I have regretted it? And will you tell them all that I have thought of them every day, and that my heart is faithful to them everywhere?”

“In my fanciful times, I fancy that they might be anywhere; and I almost expect to see their dear faces on the bridges or the quays.

And she tells Mr. Clennam how well her family have adapted themselves to their new station in life. But Amy worries:

“I find that I cannot learn. Mrs General is always with us, and we speak French and speak Italian, and she takes pains to form us in many ways … As for me, I am so slow that I scarcely get on at all.”

Amy confides in Mr. Clennam, she says, as she feels he is the only person who will understand. She misses the old place, and the old people there, and her old relationship with her father. She feels that he still needs her, but believes that he cannot admit it:

“I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him. Changed as he is, and inexpressibly blest and thankful as I always am to know it, the old sorrowful feeling of compassion comes upon me sometimes with such strength that I want to put my arms round his neck, tell him how I love him, and cry a little on his breast …I struggle with the feeling that I have come to be at a distance from him; and that even in the midst of all the servants and attendants, he is deserted, and in want of me.”

There is one more worry, that Amy has. She does not want Mr. Clennam to think of her as having changed in any way. She could not bear it, if he, of all people, who had been so kind to her, should think of her:

“as the daughter of a rich person; that you will never think of me as dressing any better, or living any better, than when you first knew me. That you will remember me only as the little shabby girl you protected with so much tenderness”

Little Dorrit in the Marshalsea (Sarah Pickering)

And she signs her letter with the words “Your poor child, Little Dorrit”.

This short chapter is devoted to a letter from Little Dorrit to Arthur Clennam.

'Little Dorrit' in the 1987 BBC miniseries, (Sarah Pickering)

Little Dorrit makes it clear than she does not expect Mr. Clennam will have thought of her at all, but says that she will always remember his kindness to her, when she had no other friends. And then she goes on to clarify that she does not have any friends now either. However, she says, the purpose of her letter is to tell him that she has met Mrs. Gowan and that the young lady says she is “‘very well and very happy.’ And she looked most beautiful … who could help loving so beautiful and winning a creature!”

However, Amy has reservations about Mrs. Gowan’s husband:

“she is very fond of him, but I thought he was not earnest enough—I don’t mean in that respect—I mean in anything…. if I was Mrs Gowan (what a change that would be, and how I must alter to become like her!) I should feel that I was rather lonely and lost, for the want of some one who was steadfast and firm in purpose.”

Amy talks very poignantly about her old life, and how she misses it. We learn that the Plornishes’ business “which my dear father bought for them” is flourishing and that Mr. Nandy is now able to live with his family, and she hopes they are all happy. Amy is worried about Maggy:

“Will you go and tell her, as a strict secret, with my love, that she never can have regretted our separation more than I have regretted it? And will you tell them all that I have thought of them every day, and that my heart is faithful to them everywhere?”

“In my fanciful times, I fancy that they might be anywhere; and I almost expect to see their dear faces on the bridges or the quays.

And she tells Mr. Clennam how well her family have adapted themselves to their new station in life. But Amy worries:

“I find that I cannot learn. Mrs General is always with us, and we speak French and speak Italian, and she takes pains to form us in many ways … As for me, I am so slow that I scarcely get on at all.”

Amy confides in Mr. Clennam, she says, as she feels he is the only person who will understand. She misses the old place, and the old people there, and her old relationship with her father. She feels that he still needs her, but believes that he cannot admit it:

“I often feel the old sad pity for—I need not write the word—for him. Changed as he is, and inexpressibly blest and thankful as I always am to know it, the old sorrowful feeling of compassion comes upon me sometimes with such strength that I want to put my arms round his neck, tell him how I love him, and cry a little on his breast …I struggle with the feeling that I have come to be at a distance from him; and that even in the midst of all the servants and attendants, he is deserted, and in want of me.”

There is one more worry, that Amy has. She does not want Mr. Clennam to think of her as having changed in any way. She could not bear it, if he, of all people, who had been so kind to her, should think of her:

“as the daughter of a rich person; that you will never think of me as dressing any better, or living any better, than when you first knew me. That you will remember me only as the little shabby girl you protected with so much tenderness”

Little Dorrit in the Marshalsea (Sarah Pickering)

And she signs her letter with the words “Your poor child, Little Dorrit”.

message 76:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 26, 2020 03:58AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

This was such a touching, poignant chapter, to close installment 11. It is the first time we have been privy to Amy’s inner thoughts, and perhaps heralds a switch of focus.

The letter is an account of her doubts, feelings, longings, and nostalgia. She is homesick for the only place which has been a home to her; a place where she found people to be genuine, and not fashionable tourists, or needing to be “formed” to fit into polite society. She is lonely wherever they go, and sad that nobody needs her any more. And she knows that her father is not happy.

The ending makes us wonder why a grown-up woman should refer to herself herself as a child. Is this perhaps because she believes that Arthur Clennam views her that way, and likes to call her “Little Dorrit”? And why has she written to him at all? Is it to tell him about Minnie Gowan, as she says? Too much of the letter seems cathartic, if that is really all it is.

Charles Dickens’s original readers had a month in which to speculate.

The letter is an account of her doubts, feelings, longings, and nostalgia. She is homesick for the only place which has been a home to her; a place where she found people to be genuine, and not fashionable tourists, or needing to be “formed” to fit into polite society. She is lonely wherever they go, and sad that nobody needs her any more. And she knows that her father is not happy.

The ending makes us wonder why a grown-up woman should refer to herself herself as a child. Is this perhaps because she believes that Arthur Clennam views her that way, and likes to call her “Little Dorrit”? And why has she written to him at all? Is it to tell him about Minnie Gowan, as she says? Too much of the letter seems cathartic, if that is really all it is.

Charles Dickens’s original readers had a month in which to speculate.

message 77:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 26, 2020 03:47AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more …

Little Dorrit:

In an article entitled “Dickens’s ‘Little Dorrit’ Still Alive?”, the New York Times of 16th December 1906 claimed that the character Amy Dorrit had been inspired by Mary Ann Cooper (née Mitton). She was then an old lady of 94, slightly deaf, and suffering from rheumatism. She lived in a house on Hatton Road, Southgate, to the west of London, in part of the area where London’s Heathrow Airport is now built. She had strong memories of “my Charles” although her memories of “Phiz” were vaguer.

As a child, in 1822, Mary Ann Mitton had lived with her parents in Clarendon Square, opposite the Dickens family. The young Charles Dickens sometimes visited the family as a child, and Mary Ann and Charles became friends. The friendship lasted for many years. Mary Ann had not been a child in the Marshalsea, but Charles Dickens took the name he had called her by, for “Little Dorrit”.

There doesn’t seem to be anything to corroborate this in Charles Dickens’s letters however, so it could be, as the New York Times suggested, that Mary Ann Cooper’s memories of that time had been “embellished through much repeating”.

Wishful thinking, perhaps?

Little Dorrit:

In an article entitled “Dickens’s ‘Little Dorrit’ Still Alive?”, the New York Times of 16th December 1906 claimed that the character Amy Dorrit had been inspired by Mary Ann Cooper (née Mitton). She was then an old lady of 94, slightly deaf, and suffering from rheumatism. She lived in a house on Hatton Road, Southgate, to the west of London, in part of the area where London’s Heathrow Airport is now built. She had strong memories of “my Charles” although her memories of “Phiz” were vaguer.

As a child, in 1822, Mary Ann Mitton had lived with her parents in Clarendon Square, opposite the Dickens family. The young Charles Dickens sometimes visited the family as a child, and Mary Ann and Charles became friends. The friendship lasted for many years. Mary Ann had not been a child in the Marshalsea, but Charles Dickens took the name he had called her by, for “Little Dorrit”.

There doesn’t seem to be anything to corroborate this in Charles Dickens’s letters however, so it could be, as the New York Times suggested, that Mary Ann Cooper’s memories of that time had been “embellished through much repeating”.

Wishful thinking, perhaps?

Poor Amy. She must be so lonely. I wonder if she ended her letter as “Your poor child, Little Dorrit” because she doesn't want Arthur to think she is making a pass at him?

Poor Amy. She must be so lonely. I wonder if she ended her letter as “Your poor child, Little Dorrit” because she doesn't want Arthur to think she is making a pass at him? And I am glad to know Maggy has someone looking after her.

Edit: Or "Your poor child, Little Dorrit” means I am still me.

Everything about Amy makes me sad right now. She is so lonely, separated from those she loves, like Maggie, and so out of place where she is, and then so in love with Arthur and trying not to give herself away.

Everything about Amy makes me sad right now. She is so lonely, separated from those she loves, like Maggie, and so out of place where she is, and then so in love with Arthur and trying not to give herself away.I think the way she signed the letter is her plea to mean the same to him as she did before. She must truly be afraid that she will come not to matter to him at all, especially now that she does not need financial help.

message 80:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 27, 2020 03:11AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I agree, Debra and Sara, Little Dorrit is feeling so sad and alone. This letter is straight from the heart, and the reason she gives (because she has met Minnie Gowan) is not the only one.

She is far away with none of her old friends or old familiar places, and she thinks Arthur's life will have moved on without her. It is only natural, and easy to forget those who have left for pastures new, even though they might yearn for the old times.

Also, Amy now has no central focus. She is not even allowed to help her father. Her whole reason for living is to be useful and help others. Now she has lost even that.

No illustrators seem to have provided work for this chapter (I searched far and wide!) but I do like the actress from the earlier 1987 series in this part, as she has quite an old face.

She is far away with none of her old friends or old familiar places, and she thinks Arthur's life will have moved on without her. It is only natural, and easy to forget those who have left for pastures new, even though they might yearn for the old times.

Also, Amy now has no central focus. She is not even allowed to help her father. Her whole reason for living is to be useful and help others. Now she has lost even that.

No illustrators seem to have provided work for this chapter (I searched far and wide!) but I do like the actress from the earlier 1987 series in this part, as she has quite an old face.

Book II: Chapter 5:

This begins the 12th installment.

The Dorrit family have now stayed a month or two in Venice. Mr. Dorrit decides he wishes to consult privately with Mrs. General, on some matter. He sends Mr. Tinkler, his valet, to her spacious apartment. Mrs. General immediately agrees to see Mr. Dorrit and is led “quite a walk, by mysterious staircases and corridors”, by the valet, to Mr. Dorrit’s apartment. This is also huge and palatial:

“with … a prospect of beautiful church-domes rising into the blue sky sheer out of the water which reflected them, and a hushed murmur of the Grand Canal laving the doorways below, where his gondolas and gondoliers attended his pleasure.”

Mr. Dorrit is keen to tell Mrs. General what is on his mind, without interruption, and puts her in her place more than once:

“‘I took the liberty—’

‘By no means,’ Mrs General interposed. ‘I was quite at your disposition. I had had my coffee.’

‘—I took the liberty,’ said Mr Dorrit again, with the magnificent placidity of one who was above correction,“

The matter Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to discuss, is Amy, but he approaches the subject carefully. He suggests that there is a difference between his two daughters which Mrs. General immediately says is true:

“Fanny … has force of character and self-reliance. Amy, none.”

At this point, the narrator makes an impassioned plea for Amy, commending her enormous strength of character through all the family’s trials in the Marshalsea.

Mr. Dorrit says there is something wrong with Amy; that she is not “so to speak, one of ourselves. He insists, however, that Amy has always been his favourite child. Mrs. General replies that there is no accounting for these partialities. She asserts that Fanny:

“at present forms too many opinions. Perfect breeding forms none, and is never demonstrative”

and that she has attempted to persuade Amy to form a demeanour. But Amy continues to “wonder exceedingly at Venice. I have mentioned to her that it is better not to wonder.”

Also, since, Mrs. General says, she believes Mr. Dorrit has:

“been accustomed to exercise influence over the minds of others.’

‘Hum—madam,’ said Mr Dorrit, ‘I have been at the head of—ha of a considerable community.“

she suggests that he should speak to Amy himself.

Mr. Dorrit is perfectly satisfied that the proprieties have now been observed, and he will not be stepping on Mrs. General’s toes if he talks to Amy about her behaviour.

He now sends his valet Mr. Tinkler for Amy and asks Mrs. General to stay for the conversation which will follow. Mr. Dorrit is suspicious of his valet, forever conscious of the fragility of his new position:

“Mr Dorrit looked severely at him, and also kept a jealous eye upon him until he went out at the door, mistrusting that he might have something in his mind prejudicial to the family dignity; that he might have even got wind of some Collegiate joke before he came into the service, and might be derisively reviving its remembrance at the present moment.”

When Amy arrives, her father asks her why she doesn’t seem to feel at home in Venice, and she replies that she needs a little time. But by using the word “father” Amy provides a convenient instruction point for Mrs. General to remonstrate with her:

“Papa is a preferable mode of address,’ observed Mrs General. ‘Father is rather vulgar, my dear. The word Papa, besides, gives a pretty form to the lips. Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism are all very good words for the lips: especially prunes and prism.”

Poor Little Dorrit is confused and forlorn, and desperate to please her father. But Mr. Dorrit becomes increasingly agitated, and less comprehensible. He accuses her of not doing what becomes her station, and embarrassing him. He also becomes angry because she constantly reminds him of their time in the Marshalsea—even though she never mentions it outright. He was head of the Marshalsea, he reminds her, and people respected Amy and gave her a special position because of it. Despite the fact that (Mr. Dorrit says) he suffered there more than anyone, he has moved on and so have Fanny and Edward. He has even provided her with an accomplished and highly bred lady to guide her, and yet Amy sits in the corner and mopes.

Even though Mr. Dorrit complains so much about how much Amy has hurt him, he never looks at her “attentive, uncomplainingly shocked face”. Amy bears all these reproaches. She:

“wished to take her seat beside him, and comfort him, and be again full of confidence with him, and of usefulness to him … her touch was tender and quiet, and in the expression of her dejected figure there was no blame—nothing but love.”

Eventually Mr. Dorrit’s passionate outburst dies, and he becomes dejected, exclaiming that he “was a poor ruin and a poor wretch in the midst of his wealth” and is soothed by Amy. The narrator observes that, significantly:

“With one remarkable exception, to be recorded in its place, this was the only time, in his life of freedom and fortune, when he spoke to his daughter Amy of the old days.”

The chapter ends with a surprising incident.

We have had a lengthy description of how Mr. Frederick Dorrit spends his days, looking at the paintings, and enjoying the fact that Amy might accompany him. When the rest of the family arrive for breakfast, Amy asks her father if he minds her going on a visit to Mrs. Gowen, as she and her husband have also arrived in Venice. Fanny and Mrs. General protest because the Gowens are not of their social circle, but when Edward mentions that they are friends with the Merdles they all become excited at the idea of a link to the great and famous Mr. Merdle and allow Amy’s visit.

When Amy leaves the room Frederick Dorrit loses his temper, to everyone’s astonishment. He accuses Fanny of having no heart in the way she treats Amy, earnestly and vehemently crying out “Brother! I protest against it!”

Fanny says she is only anxious for the family credit, thinking of the family’s honour, but he turns on her:

Frederick Dorrit and Fanny Dorrit - James Mahoney

“where’s your affectionate invaluable friend? Where’s your devoted guardian? Where’s your more than mother? How dare you set up superiorities against all these characters combined in your sister? For shame, you false girl, for shame!”

Mr. William Dorrit says nothing throughout, but looks perplexed and doubtful. After his brother leaves the room, he, Edward (Tip) and Fanny agree not to tell Amy what has happened, saying that there must be something wrong with Frederick. Fanny then spends the rest of the day with Amy:

“passing the greater part of it in violent fits of embracing her, and in alternately giving her brooches, and wishing herself dead.”

This begins the 12th installment.

The Dorrit family have now stayed a month or two in Venice. Mr. Dorrit decides he wishes to consult privately with Mrs. General, on some matter. He sends Mr. Tinkler, his valet, to her spacious apartment. Mrs. General immediately agrees to see Mr. Dorrit and is led “quite a walk, by mysterious staircases and corridors”, by the valet, to Mr. Dorrit’s apartment. This is also huge and palatial:

“with … a prospect of beautiful church-domes rising into the blue sky sheer out of the water which reflected them, and a hushed murmur of the Grand Canal laving the doorways below, where his gondolas and gondoliers attended his pleasure.”

Mr. Dorrit is keen to tell Mrs. General what is on his mind, without interruption, and puts her in her place more than once:

“‘I took the liberty—’

‘By no means,’ Mrs General interposed. ‘I was quite at your disposition. I had had my coffee.’

‘—I took the liberty,’ said Mr Dorrit again, with the magnificent placidity of one who was above correction,“

The matter Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to discuss, is Amy, but he approaches the subject carefully. He suggests that there is a difference between his two daughters which Mrs. General immediately says is true:

“Fanny … has force of character and self-reliance. Amy, none.”

At this point, the narrator makes an impassioned plea for Amy, commending her enormous strength of character through all the family’s trials in the Marshalsea.

Mr. Dorrit says there is something wrong with Amy; that she is not “so to speak, one of ourselves. He insists, however, that Amy has always been his favourite child. Mrs. General replies that there is no accounting for these partialities. She asserts that Fanny:

“at present forms too many opinions. Perfect breeding forms none, and is never demonstrative”

and that she has attempted to persuade Amy to form a demeanour. But Amy continues to “wonder exceedingly at Venice. I have mentioned to her that it is better not to wonder.”

Also, since, Mrs. General says, she believes Mr. Dorrit has:

“been accustomed to exercise influence over the minds of others.’

‘Hum—madam,’ said Mr Dorrit, ‘I have been at the head of—ha of a considerable community.“

she suggests that he should speak to Amy himself.

Mr. Dorrit is perfectly satisfied that the proprieties have now been observed, and he will not be stepping on Mrs. General’s toes if he talks to Amy about her behaviour.

He now sends his valet Mr. Tinkler for Amy and asks Mrs. General to stay for the conversation which will follow. Mr. Dorrit is suspicious of his valet, forever conscious of the fragility of his new position:

“Mr Dorrit looked severely at him, and also kept a jealous eye upon him until he went out at the door, mistrusting that he might have something in his mind prejudicial to the family dignity; that he might have even got wind of some Collegiate joke before he came into the service, and might be derisively reviving its remembrance at the present moment.”

When Amy arrives, her father asks her why she doesn’t seem to feel at home in Venice, and she replies that she needs a little time. But by using the word “father” Amy provides a convenient instruction point for Mrs. General to remonstrate with her:

“Papa is a preferable mode of address,’ observed Mrs General. ‘Father is rather vulgar, my dear. The word Papa, besides, gives a pretty form to the lips. Papa, potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism are all very good words for the lips: especially prunes and prism.”

Poor Little Dorrit is confused and forlorn, and desperate to please her father. But Mr. Dorrit becomes increasingly agitated, and less comprehensible. He accuses her of not doing what becomes her station, and embarrassing him. He also becomes angry because she constantly reminds him of their time in the Marshalsea—even though she never mentions it outright. He was head of the Marshalsea, he reminds her, and people respected Amy and gave her a special position because of it. Despite the fact that (Mr. Dorrit says) he suffered there more than anyone, he has moved on and so have Fanny and Edward. He has even provided her with an accomplished and highly bred lady to guide her, and yet Amy sits in the corner and mopes.

Even though Mr. Dorrit complains so much about how much Amy has hurt him, he never looks at her “attentive, uncomplainingly shocked face”. Amy bears all these reproaches. She:

“wished to take her seat beside him, and comfort him, and be again full of confidence with him, and of usefulness to him … her touch was tender and quiet, and in the expression of her dejected figure there was no blame—nothing but love.”

Eventually Mr. Dorrit’s passionate outburst dies, and he becomes dejected, exclaiming that he “was a poor ruin and a poor wretch in the midst of his wealth” and is soothed by Amy. The narrator observes that, significantly:

“With one remarkable exception, to be recorded in its place, this was the only time, in his life of freedom and fortune, when he spoke to his daughter Amy of the old days.”

The chapter ends with a surprising incident.

We have had a lengthy description of how Mr. Frederick Dorrit spends his days, looking at the paintings, and enjoying the fact that Amy might accompany him. When the rest of the family arrive for breakfast, Amy asks her father if he minds her going on a visit to Mrs. Gowen, as she and her husband have also arrived in Venice. Fanny and Mrs. General protest because the Gowens are not of their social circle, but when Edward mentions that they are friends with the Merdles they all become excited at the idea of a link to the great and famous Mr. Merdle and allow Amy’s visit.

When Amy leaves the room Frederick Dorrit loses his temper, to everyone’s astonishment. He accuses Fanny of having no heart in the way she treats Amy, earnestly and vehemently crying out “Brother! I protest against it!”

Fanny says she is only anxious for the family credit, thinking of the family’s honour, but he turns on her:

Frederick Dorrit and Fanny Dorrit - James Mahoney

“where’s your affectionate invaluable friend? Where’s your devoted guardian? Where’s your more than mother? How dare you set up superiorities against all these characters combined in your sister? For shame, you false girl, for shame!”

Mr. William Dorrit says nothing throughout, but looks perplexed and doubtful. After his brother leaves the room, he, Edward (Tip) and Fanny agree not to tell Amy what has happened, saying that there must be something wrong with Frederick. Fanny then spends the rest of the day with Amy:

“passing the greater part of it in violent fits of embracing her, and in alternately giving her brooches, and wishing herself dead.”

message 82:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 27, 2020 03:29AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

It's remarkable to think that when Charles Dickens's original readers finished this new installment, they would have been reading Little Dorrit for a whole year!

I think we need a bit of the ridiculous "potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism" after the poignancy of Amy's letter :) And what about Frederick getting his courage at last?

Yes, this is a good chapter!

I think we need a bit of the ridiculous "potatoes, poultry, prunes, and prism" after the poignancy of Amy's letter :) And what about Frederick getting his courage at last?

Yes, this is a good chapter!

I think Mr. Dorrit assails Amy because he cannot, despite all his pompous efforts, forget the Marshalsea himself. He had position there that was freely given and respect from every person he met; here he feels slighted constantly and on edge lest someone discover who he is. Amy cannot help reminding him of his previous life by just her presence, but the truth is, he can never forget it, whether she is there or not. He seems almost pitiable, but as always, he gives no thought to the affect his words are having on Amy or her misery in being uprooted from her life. Even saying it is "done for her" is an afterthought.

I think Mr. Dorrit assails Amy because he cannot, despite all his pompous efforts, forget the Marshalsea himself. He had position there that was freely given and respect from every person he met; here he feels slighted constantly and on edge lest someone discover who he is. Amy cannot help reminding him of his previous life by just her presence, but the truth is, he can never forget it, whether she is there or not. He seems almost pitiable, but as always, he gives no thought to the affect his words are having on Amy or her misery in being uprooted from her life. Even saying it is "done for her" is an afterthought.Of course, the conversation regarding the Merdles and Gowans is maddening. The Gowans go from unacceptable to acceptable in the blink of an eye. How shallow they all are!

Bravo for Uncle Frederick. Someone finally pounds a fist and takes up for Amy. Fanny cries and spends the day petting Amy, but by tomorrow she will be back to complaining that Amy disgraces them, so it means little.

I agree with Sara that Mr. Dorrit's criticism of Amy is about his inability himself to forget about the Marshalsea and his fear of being discovered. He did have some respect in his old life, so he says, but he was very pompous then already which already just hiding a very insecure nature. He was acting the part of the fine English gentleman even then but now with his money and the ability to be a fine English Gentleman again for real he is just as insecure and pompous. But now he's also very anxious all the time, worried that others see the "Marshalsea man" or will find out about his past. For instance, at the hotel when he was so upset when he had to wait a half hour for his room because The Merdle were using it, he kept asking, "why, why do you do this to me?" He fears it's because they don't respect him or see him as a Gentleman but they'd never met him! Amy's not "coming along" makes him even more fearful of being found out. I can't recall one scene in which he is happy and relaxed with his freedom and wealth. I know some people despise him; and I do laugh at his pomposity but now I rather feel sorry for him because I think he's suffering from anxiety and insecurity and is all the time. That doesn't mean it's okay to take it out on Amy as he does, but he can't help himself, he's so desperate. He's going to give himself a stroke or a heart attack if he doesn't chill out.

I agree with Sara that Mr. Dorrit's criticism of Amy is about his inability himself to forget about the Marshalsea and his fear of being discovered. He did have some respect in his old life, so he says, but he was very pompous then already which already just hiding a very insecure nature. He was acting the part of the fine English gentleman even then but now with his money and the ability to be a fine English Gentleman again for real he is just as insecure and pompous. But now he's also very anxious all the time, worried that others see the "Marshalsea man" or will find out about his past. For instance, at the hotel when he was so upset when he had to wait a half hour for his room because The Merdle were using it, he kept asking, "why, why do you do this to me?" He fears it's because they don't respect him or see him as a Gentleman but they'd never met him! Amy's not "coming along" makes him even more fearful of being found out. I can't recall one scene in which he is happy and relaxed with his freedom and wealth. I know some people despise him; and I do laugh at his pomposity but now I rather feel sorry for him because I think he's suffering from anxiety and insecurity and is all the time. That doesn't mean it's okay to take it out on Amy as he does, but he can't help himself, he's so desperate. He's going to give himself a stroke or a heart attack if he doesn't chill out.

I hope Amy does not change to suit her father. I like her much better the way she is. Also, I hope she keeps in touch with Arthur. It seems that she can truly be herself when she is corresponding with him. I really like the use of the letter in chapter 4 to let us know what is going on in Amy's world. It also lets us know what's going on with the people, like Martha, who were left behind.

I hope Amy does not change to suit her father. I like her much better the way she is. Also, I hope she keeps in touch with Arthur. It seems that she can truly be herself when she is corresponding with him. I really like the use of the letter in chapter 4 to let us know what is going on in Amy's world. It also lets us know what's going on with the people, like Martha, who were left behind.I wonder if there is any significance in Tip's looking "perplexed and doubtful" after the scene with Amy's uncle. Is he finally thinking of something beyond his immediate concerns or does he just totally not understand what his uncle is going on about?

message 86:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 27, 2020 11:38AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Sara and Anne - Exactly so :) Except right at the beginning, when he does seem insufferable, I always find it difficult to laugh at Mr. Dorrit's self-importance, pomposity and grandeur. It is a clever satire, to make us smile, but at its heart there is an unhappy, insecure man, whom we should pity.

The first definite confirmation of this is when he learns he is to be freed, and he does not know how to behave. He has carved himself a place in the Marshalsea, and, oddly, is about to lose everything he has invested in - but emotionally, not financially. His character's worth actually shows itself in the little gifts he gives to the other debtors, as he leaves. Yes, this is partly for show, and we dislike him for it, thinking that it is pure hypocrisy. But it is also because he truly believes that this is what is proper; it is the act of a gentleman.

He belongs to a world that is beginning to die, as the Industrial Revolution takes hold, and at the very least he is likely to become a lost soul, as so many of the minor gentry did (though the aristocracy usually survived). We have hints that it could be even worse.

Now we have many indications piling up, to show us that Mr Dorrit is a mass of insecurities, seeing other laughing at him behind his back, when they are merely performing their duties. Amy loves him and makes excuses for him, because she knows that he cannot help what he has become.

Katy - Your thoughts about Tip are nicely observed! It would be nice to think that he is not quite so much of a dunderhead as we have seen so far.

I think there are quite a few characters in this novel who potentially have their own journeys.

The first definite confirmation of this is when he learns he is to be freed, and he does not know how to behave. He has carved himself a place in the Marshalsea, and, oddly, is about to lose everything he has invested in - but emotionally, not financially. His character's worth actually shows itself in the little gifts he gives to the other debtors, as he leaves. Yes, this is partly for show, and we dislike him for it, thinking that it is pure hypocrisy. But it is also because he truly believes that this is what is proper; it is the act of a gentleman.

He belongs to a world that is beginning to die, as the Industrial Revolution takes hold, and at the very least he is likely to become a lost soul, as so many of the minor gentry did (though the aristocracy usually survived). We have hints that it could be even worse.

Now we have many indications piling up, to show us that Mr Dorrit is a mass of insecurities, seeing other laughing at him behind his back, when they are merely performing their duties. Amy loves him and makes excuses for him, because she knows that he cannot help what he has become.

Katy - Your thoughts about Tip are nicely observed! It would be nice to think that he is not quite so much of a dunderhead as we have seen so far.

I think there are quite a few characters in this novel who potentially have their own journeys.

Jean wrote, "We have hints that it could be even worse."

Jean wrote, "We have hints that it could be even worse."Jean, I don't recall such hints. Would you mind reminding me?

message 88:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 27, 2020 12:39PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

By his behaviour to his loved ones, and his servants, Anne. As you yourself observed "He's going to give himself a stroke or a heart attack if he doesn't chill out."

Jean, I too laughed at Mrs. General saying “Papa, potatoes, poultry, prune, and prism”. Great satire. What a great pompous fool she is. Frederick is showing himself as the only Dorrit besides Amy who has a heart, honesty, and integrity. I love how he stands up for Amy.

Jean, I too laughed at Mrs. General saying “Papa, potatoes, poultry, prune, and prism”. Great satire. What a great pompous fool she is. Frederick is showing himself as the only Dorrit besides Amy who has a heart, honesty, and integrity. I love how he stands up for Amy.

message 90:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 27, 2020 12:39PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Me too Mona! And Frederick really came out of left field :)

Interesting too how the others (variously) felt a little ashamed of themselves. Fanny still perhaps has some saving graces ... or is this guilty behaviour short-lived, and will her haughtiness return, I wonder. She does seem to love Amy, deep down :)

Interesting too how the others (variously) felt a little ashamed of themselves. Fanny still perhaps has some saving graces ... or is this guilty behaviour short-lived, and will her haughtiness return, I wonder. She does seem to love Amy, deep down :)

Ok. I thought you meant there were hints about the gentry and what was happening to them at this time in the novel; the Industrial Revolution. But you were referring to hints about his becoming a lost soul. Agree. Plenty of hints that he's breaking down and lost which is how we've been describing Amy. Only Amy is stronger than him. She's missing her friends - from a life at the Marshalsea to Venice is an overwhelming change especially to someone as sensitive as our Amy.

Ok. I thought you meant there were hints about the gentry and what was happening to them at this time in the novel; the Industrial Revolution. But you were referring to hints about his becoming a lost soul. Agree. Plenty of hints that he's breaking down and lost which is how we've been describing Amy. Only Amy is stronger than him. She's missing her friends - from a life at the Marshalsea to Venice is an overwhelming change especially to someone as sensitive as our Amy. But her father is a different case. I just had an image of him lying in bed, mentally ill or just ill, with Amy caring for him as she used to do. He raised Amy to take care of all of his needs (and others) . It always looked like he was using her as his cook, valet, etc.. But she was always very loving, but now he can't allow himself to have that love. Propriety dictates otherwise, That's a big loss for him, whether he knows it or not. And he's not getting love or support from anyone else. HIs money, fine manners and clothes are not going to support his fragile ego nor soothe his increasingly nervous soul.

Side note:

I happen to have just finished The House of Mirth and am writing my review and the tradeoffs are still the same in Wharton's society as they were in Dickens'. They're the same today in certain circles. Human nature doesn't learn or change.'

I also loved how Frederick stood up for Amy. What a surprise from such a quiet go-along man. I loved it.

I also loved how Frederick stood up for Amy. What a surprise from such a quiet go-along man. I loved it. I think Fanny loves Amy. She gets mad and haughty and guilty and it's always about appearances. She is always sorry later and loving again. I agree with Jean that deep down she loves her sister.

Amy continues to be saintly, never protesting at all the criticism thrown at her, or even forthrightly stating her feelings except in the letter to Arthur. In their better moments, her family does see this as a reproach and it makes them uncomfortable.

Amy continues to be saintly, never protesting at all the criticism thrown at her, or even forthrightly stating her feelings except in the letter to Arthur. In their better moments, her family does see this as a reproach and it makes them uncomfortable.

message 94:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 28, 2020 03:42AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Robin P wrote: "Amy continues to be saintly, never protesting at all the criticism thrown at her, or even forthrightly stating her feelings except in the letter to Arthur ..."

Hmmm. I don't want to be picky, but here goes ...

A regular criticism of both Amy Dorrit and Little Nell (in The Old Curiosity Shop) is that they are unrealistic portrayals. I'm not sure if this is the sense in which you mean "saintly" Robin, but I think you probably do, since googling the word, the first sentence of the definition says "If someone is saintly, they're so perfect that they're almost too good to be true.".

Critics also complain about Charles Dickens and his "noble poor": the tendency to see the good aspects of poor people, and the worst in the wealthy. His heroes often have humble origins.

And yet - I am drawn to Amy, and don't find her unbelievable, just kind, loving and good. We see that she find it difficult sometimes, just as anyone would! Here are some examples from the first part of this chapter:

"a rather forlorn glance at that eminent varnisher,"

"her desire to submit herself to Mrs General and please him."

"the fingers of her lightly folded hands were agitated, and there was repressed emotion in her face"

"She laid her hand on his arm ... There was a reproach in the touch so addressed to him that she had not foreseen, or she would have withheld her hand"

and so on. So I do agree that that she tries very had to be as good as she can be, but I have problems with the word "saintly", with the implications it often has nowadays. I feel very sorry for Amy, who feels like a real person to me. The author has done his job well, as when the narrator says "poor Amy" I agree with him! And having such a character allows Frederick to show his true colours too :)

As I mentioned after chapter 4 (the letter) we are beginning now to see Amy's inner feelings more. Previously, she accomplished her goals so effectively that we weren't really privy to how she felt. We just saw her actions, and how others viewed her.

Hmmm. I don't want to be picky, but here goes ...

A regular criticism of both Amy Dorrit and Little Nell (in The Old Curiosity Shop) is that they are unrealistic portrayals. I'm not sure if this is the sense in which you mean "saintly" Robin, but I think you probably do, since googling the word, the first sentence of the definition says "If someone is saintly, they're so perfect that they're almost too good to be true.".

Critics also complain about Charles Dickens and his "noble poor": the tendency to see the good aspects of poor people, and the worst in the wealthy. His heroes often have humble origins.

And yet - I am drawn to Amy, and don't find her unbelievable, just kind, loving and good. We see that she find it difficult sometimes, just as anyone would! Here are some examples from the first part of this chapter:

"a rather forlorn glance at that eminent varnisher,"

"her desire to submit herself to Mrs General and please him."

"the fingers of her lightly folded hands were agitated, and there was repressed emotion in her face"

"She laid her hand on his arm ... There was a reproach in the touch so addressed to him that she had not foreseen, or she would have withheld her hand"

and so on. So I do agree that that she tries very had to be as good as she can be, but I have problems with the word "saintly", with the implications it often has nowadays. I feel very sorry for Amy, who feels like a real person to me. The author has done his job well, as when the narrator says "poor Amy" I agree with him! And having such a character allows Frederick to show his true colours too :)

As I mentioned after chapter 4 (the letter) we are beginning now to see Amy's inner feelings more. Previously, she accomplished her goals so effectively that we weren't really privy to how she felt. We just saw her actions, and how others viewed her.

message 95:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 28, 2020 03:56AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 6:

This is the middle chapter of Book 2’s second installment, and a long, dark chapter indeed.

We begin with a description of Henry Gowan’s perversities. He curses both ways of life he has attempted: the way his family would have liked him to follow, and the way of an artist. Henry has a perverted delight in “bringing deserving things down by setting undeserving things up”. He therefore declares that all Art is “trash” and furthermore, that he turns out nothing else himself. Henry Gowan makes it clear that he is poor and by doing so, reminds everybody that he should be rich. He publicly discusses his family, the Barnacles, so that everyone is aware of his connection to them. And he makes absolutely sure that it is generally known that he had married against the wishes of his family, and beneath his station.

His wife is fully aware of this:

“Minnie Gowan felt sensible of being usually regarded as the wife of a man who had made a descent in marrying her, but whose chivalrous love for her had cancelled that inequality.”

“Monsieur Blandois of Paris” has accompanied them from Geneva to Venice, and spends a lot of his time with Mr. Gowan. At first Mr. Gowan could not decide whether he liked or disliked Blandois; whether to “kick him or encourage him”. But since Minnie definitely dislikes the man, Henry had decided to befriend him. The narrator explains that Henry wants to assert his independence, after his wife’s father had paid his debts. Also, he likes setting up Blandois as the elegant Type. Because Blandois’ mannerisms are so exaggerated, he becomes a satire of others. Gowan finds him a kind of caricature. He doesn’t care for Blandois at all, and if he had any reason to throw him out the window he would, but for now Blandois is his almost constant companion.

Amy visits Mrs. Gowan, as she had wished, but feels trepidation, as Fanny insists on coming along. Fanny is very critical to Amy of the lodgings that the Gowans have taken, and the grotesque descriptions show that the buildings in the area are full of decay, and their lodgings above a Bank are full of “weird furniture … forlornly faded and musty, and … the prevailing Venetian odour of bilge water and an ebb tide on a weedy shore was very strong”.

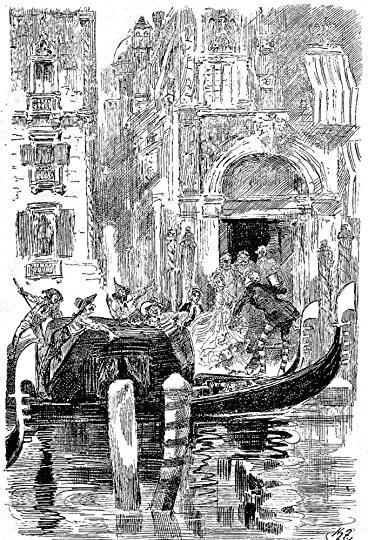

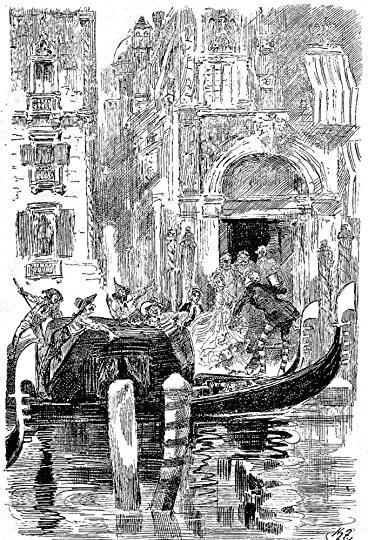

'Meeting an Acquaintance' - Harry Furniss

When they are shown in to see Mrs. Gowan, Fanny is “excessively courteous” to her, and says that she has heard that the Gowans knew the Merdles. Mrs. Gowan replies that they are Henry’s friends, whom she has not yet met, but expects to be introduced to in Rome. This makes Fanny feel superior, and she ensures that Minnie knows that she has already met Mrs. Merdle, by saying that she thinks Mrs. Gowan will like Mrs. Merdle. She also tells her that:

“We met her on our way here, and, to say the truth, papa was at first rather cross with her for taking one of the rooms that our people had ordered for us. However, of course, that soon blew over, and we were all good friends again.”

Amy and Minnie have not had chance to say anything to each other, but they have a silent understanding. Amy has taken everything in about Minnie, and her lodgings:

“She was quicker to perceive the slightest matter here, than in any other case—but one.”

Minnie shows Amy and Fanny into Henry’s studio, and the first thing Amy sees is Blandois, who is the model for a portrait Henry is painting. Blandois is all smooth charm and swagger, but seems strangely uneasy, and his hand starts to shake when Henry describes the painting to them:

“’There he stands, you see. A bravo waiting for his prey, a distinguished noble waiting to save his country—whatever you think he looks most like!

He was formerly in some scuffle with another murderer, or with a victim, you observe,’ said Gowan, putting in the markings of the hand with a quick, impatient, unskilful touch, ‘and these are the tokens of it. Outside the cloak, man!—Corpo di San Marco, what are you thinking of?’“

Amy, still rooted to the spot, has inadvertently locked eyes with Blandois, and Gowan’s dog senses something amiss, and gives a low growl. Henry blames Blandois for provoking the dog, “Lion”, and orders Blandois to leave the room. However, once Blandois is out of the room and the dog is submissive, Henry then kicks the dog in the head, and keeps kicking him with the heel of his boot, until his mouth is bloody. Minnie, Amy and Fanny are upset, and:

“Lion, deeply ashamed of having caused them this alarm, came trailing himself along the ground to the feet of his mistress.”

However this does not deter Henry Gowan. Despite Amy’s pleading with him to stop, he keeps kicking the poor dog, although:

“truly he was as submissive, and as sorry, and as wretched as a dog could be.”

Eventually the two sisters go, and Amy suspects that Henry Gowan has no depth of feeling, and a general lack of earnestness, which would make him drift through life.

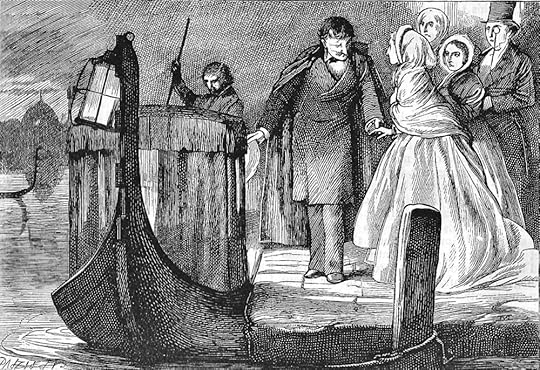

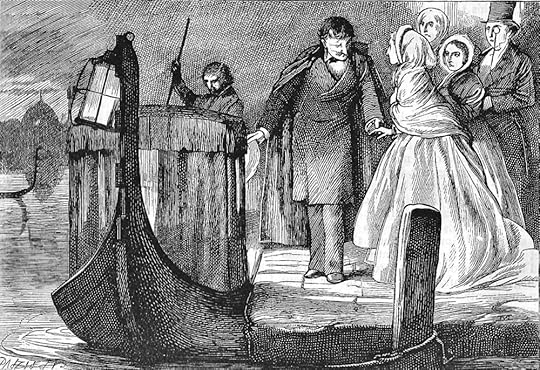

'On the Brink of the Quay' - James Mahoney

“At the water’s edge they were saluted by Blandois, who looked white enough after his late adventure, but who made very light of it notwithstanding,—laughing at the mention of Lion.”

As they glide back in their gondola, Amy becomes aware of Fanny looking more showy than she needs to. The reason is that Young Sparkler is in another gondola nearby. Fanny thinks he is probably dying for a glimpse of her, and so Amy wonders why he hasn’t called yet. Fanny thinks he is working up the courage to do so, and that she wouldn’t be surprised to see him that day. She calls him a “gaby” and a “simpleton”. She explains to Amy that his mother will pretend, for form’s sake, that the very first time they met was in the Inn Yard at Martigny:

“Don’t you see that I may have become a rather desirable match for a noddle?”

Amy is doubtful, and asks if Fanny wishes to encourage him. Her sister smiles contemptuously:

“ No, I don’t mean to encourage him. But I’ll make a slave of him.”

They find Sparkler waiting at their door, as Fanny expected. He stands up in his gondola, in order to greet them, but manages to fall down and make a fool of himself.

'Mr. Sparkler Under a Reversal of Circumstances' - Phiz

Fanny continues the charade, anxiously asking after him, and pretending she doesn’t know him. Sparkler reminds her that they met in Martigny, and says he has come to call on her brother Edward and her father. The narrator wryly remarks that:

“Miss Fanny accepting it, was squired up the great staircase by Mr Sparkler, who, if he still believed (which there is not any reason to doubt) that she had no nonsense about her, rather deceived himself.”

Mr. Dorrit continues the pretence, and “with the highest urbanity, and most courtly manners” invites Sparkler to dinner, and to the opera later. Fanny continues to entrance and entrap Sparkler:

“If Fanny had been charming in the morning, she was now thrice charming, very becomingly dressed in her most suitable colours, and with an air of negligence upon her that doubled Mr Sparkler’s fetters, and riveted them.”

Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to hire Mr. Gowan to paint portraits of the family. During their evening at the opera. Sparkler becomes even more smitten with Fanny.

As they leave the Opera, Amy sees Blandois helping Fanny into a gondola. He tells them that since they had seen Gowan, he had had a loss. His dog Lion is dead.

“‘Dead?’ echoed Little Dorrit. ‘That noble dog?’

‘Faith, dear ladies!’ said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, ‘somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!’“

This is the middle chapter of Book 2’s second installment, and a long, dark chapter indeed.

We begin with a description of Henry Gowan’s perversities. He curses both ways of life he has attempted: the way his family would have liked him to follow, and the way of an artist. Henry has a perverted delight in “bringing deserving things down by setting undeserving things up”. He therefore declares that all Art is “trash” and furthermore, that he turns out nothing else himself. Henry Gowan makes it clear that he is poor and by doing so, reminds everybody that he should be rich. He publicly discusses his family, the Barnacles, so that everyone is aware of his connection to them. And he makes absolutely sure that it is generally known that he had married against the wishes of his family, and beneath his station.

His wife is fully aware of this:

“Minnie Gowan felt sensible of being usually regarded as the wife of a man who had made a descent in marrying her, but whose chivalrous love for her had cancelled that inequality.”

“Monsieur Blandois of Paris” has accompanied them from Geneva to Venice, and spends a lot of his time with Mr. Gowan. At first Mr. Gowan could not decide whether he liked or disliked Blandois; whether to “kick him or encourage him”. But since Minnie definitely dislikes the man, Henry had decided to befriend him. The narrator explains that Henry wants to assert his independence, after his wife’s father had paid his debts. Also, he likes setting up Blandois as the elegant Type. Because Blandois’ mannerisms are so exaggerated, he becomes a satire of others. Gowan finds him a kind of caricature. He doesn’t care for Blandois at all, and if he had any reason to throw him out the window he would, but for now Blandois is his almost constant companion.

Amy visits Mrs. Gowan, as she had wished, but feels trepidation, as Fanny insists on coming along. Fanny is very critical to Amy of the lodgings that the Gowans have taken, and the grotesque descriptions show that the buildings in the area are full of decay, and their lodgings above a Bank are full of “weird furniture … forlornly faded and musty, and … the prevailing Venetian odour of bilge water and an ebb tide on a weedy shore was very strong”.

'Meeting an Acquaintance' - Harry Furniss

When they are shown in to see Mrs. Gowan, Fanny is “excessively courteous” to her, and says that she has heard that the Gowans knew the Merdles. Mrs. Gowan replies that they are Henry’s friends, whom she has not yet met, but expects to be introduced to in Rome. This makes Fanny feel superior, and she ensures that Minnie knows that she has already met Mrs. Merdle, by saying that she thinks Mrs. Gowan will like Mrs. Merdle. She also tells her that:

“We met her on our way here, and, to say the truth, papa was at first rather cross with her for taking one of the rooms that our people had ordered for us. However, of course, that soon blew over, and we were all good friends again.”

Amy and Minnie have not had chance to say anything to each other, but they have a silent understanding. Amy has taken everything in about Minnie, and her lodgings:

“She was quicker to perceive the slightest matter here, than in any other case—but one.”

Minnie shows Amy and Fanny into Henry’s studio, and the first thing Amy sees is Blandois, who is the model for a portrait Henry is painting. Blandois is all smooth charm and swagger, but seems strangely uneasy, and his hand starts to shake when Henry describes the painting to them:

“’There he stands, you see. A bravo waiting for his prey, a distinguished noble waiting to save his country—whatever you think he looks most like!

He was formerly in some scuffle with another murderer, or with a victim, you observe,’ said Gowan, putting in the markings of the hand with a quick, impatient, unskilful touch, ‘and these are the tokens of it. Outside the cloak, man!—Corpo di San Marco, what are you thinking of?’“

Amy, still rooted to the spot, has inadvertently locked eyes with Blandois, and Gowan’s dog senses something amiss, and gives a low growl. Henry blames Blandois for provoking the dog, “Lion”, and orders Blandois to leave the room. However, once Blandois is out of the room and the dog is submissive, Henry then kicks the dog in the head, and keeps kicking him with the heel of his boot, until his mouth is bloody. Minnie, Amy and Fanny are upset, and:

“Lion, deeply ashamed of having caused them this alarm, came trailing himself along the ground to the feet of his mistress.”

However this does not deter Henry Gowan. Despite Amy’s pleading with him to stop, he keeps kicking the poor dog, although:

“truly he was as submissive, and as sorry, and as wretched as a dog could be.”

Eventually the two sisters go, and Amy suspects that Henry Gowan has no depth of feeling, and a general lack of earnestness, which would make him drift through life.

'On the Brink of the Quay' - James Mahoney

“At the water’s edge they were saluted by Blandois, who looked white enough after his late adventure, but who made very light of it notwithstanding,—laughing at the mention of Lion.”

As they glide back in their gondola, Amy becomes aware of Fanny looking more showy than she needs to. The reason is that Young Sparkler is in another gondola nearby. Fanny thinks he is probably dying for a glimpse of her, and so Amy wonders why he hasn’t called yet. Fanny thinks he is working up the courage to do so, and that she wouldn’t be surprised to see him that day. She calls him a “gaby” and a “simpleton”. She explains to Amy that his mother will pretend, for form’s sake, that the very first time they met was in the Inn Yard at Martigny:

“Don’t you see that I may have become a rather desirable match for a noddle?”

Amy is doubtful, and asks if Fanny wishes to encourage him. Her sister smiles contemptuously:

“ No, I don’t mean to encourage him. But I’ll make a slave of him.”

They find Sparkler waiting at their door, as Fanny expected. He stands up in his gondola, in order to greet them, but manages to fall down and make a fool of himself.

'Mr. Sparkler Under a Reversal of Circumstances' - Phiz

Fanny continues the charade, anxiously asking after him, and pretending she doesn’t know him. Sparkler reminds her that they met in Martigny, and says he has come to call on her brother Edward and her father. The narrator wryly remarks that:

“Miss Fanny accepting it, was squired up the great staircase by Mr Sparkler, who, if he still believed (which there is not any reason to doubt) that she had no nonsense about her, rather deceived himself.”

Mr. Dorrit continues the pretence, and “with the highest urbanity, and most courtly manners” invites Sparkler to dinner, and to the opera later. Fanny continues to entrance and entrap Sparkler:

“If Fanny had been charming in the morning, she was now thrice charming, very becomingly dressed in her most suitable colours, and with an air of negligence upon her that doubled Mr Sparkler’s fetters, and riveted them.”

Mr. Dorrit says he wishes to hire Mr. Gowan to paint portraits of the family. During their evening at the opera. Sparkler becomes even more smitten with Fanny.

As they leave the Opera, Amy sees Blandois helping Fanny into a gondola. He tells them that since they had seen Gowan, he had had a loss. His dog Lion is dead.

“‘Dead?’ echoed Little Dorrit. ‘That noble dog?’

‘Faith, dear ladies!’ said Blandois, smiling and shrugging his shoulders, ‘somebody has poisoned that noble dog. He is as dead as the Doges!’“

message 96:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Oct 28, 2020 03:57AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

I think this is my least favourite chapter in the whole novel. So much hypocritical behaviour, from so many characters: Gowan, Blandois, Fanny, and Mr. Dorrit. So much manipulation of selfish ends. But it's chiefly because of the torture of that poor noble dog. Hateful. I could barely bring myself to write it. I have an inkling about who poisoned him.

These previous two chapters have been ironically named, “Something Wrong Somewhere”, when of course there is nothing at all wrong with Amy, when the family (with the exception of Frederick) all protest that there is, and this chapter is called “Something Right Somewhere” when, to be honest, it would be hard to find anything of value at all in these atrocious events.

I don’t think I can ever forget Lion. Charles Dickens loved dogs, but I wish with all my heart that he hadn’t written this horrible episode :(

I do really like all three illustrations, however.

These previous two chapters have been ironically named, “Something Wrong Somewhere”, when of course there is nothing at all wrong with Amy, when the family (with the exception of Frederick) all protest that there is, and this chapter is called “Something Right Somewhere” when, to be honest, it would be hard to find anything of value at all in these atrocious events.

I don’t think I can ever forget Lion. Charles Dickens loved dogs, but I wish with all my heart that he hadn’t written this horrible episode :(

I do really like all three illustrations, however.

I cannot bear animal cruelty and I was surprised to find it in this book. I am a dog owner and lover and think that the only reason Dickens could have included that scene inn the book is to signal 1) that Gowan, who did the kicking, is a horrible person, unkind, unempathic and awful. This does not bode well for how he will treat his wife. 2) that the dog could tell that Blandois was an awful man. Dogs know people. Blandois may have already treated the dog badly and s/he remembers or s/he could sense what a bad character he is on first meeting. Anyway, I don't know why either of those men would want to kill the dog. There is not motivation that we've seen yet. Could be either of them. Blandois has a history of murder so perhaps it was him.

I cannot bear animal cruelty and I was surprised to find it in this book. I am a dog owner and lover and think that the only reason Dickens could have included that scene inn the book is to signal 1) that Gowan, who did the kicking, is a horrible person, unkind, unempathic and awful. This does not bode well for how he will treat his wife. 2) that the dog could tell that Blandois was an awful man. Dogs know people. Blandois may have already treated the dog badly and s/he remembers or s/he could sense what a bad character he is on first meeting. Anyway, I don't know why either of those men would want to kill the dog. There is not motivation that we've seen yet. Could be either of them. Blandois has a history of murder so perhaps it was him.

Anne & Jean I think it’s very likely that Blandois poisoned the dog. He seems to be a psychopath or sociopath. Gowan is also very cruel to the dog, as well as condescending to Minnie. Gowan befriending Blandois does not reflect well on him. Birds of a feather, as the saying goes. Anne, I too find cruelty to animals abhorrent.

Anne & Jean I think it’s very likely that Blandois poisoned the dog. He seems to be a psychopath or sociopath. Gowan is also very cruel to the dog, as well as condescending to Minnie. Gowan befriending Blandois does not reflect well on him. Birds of a feather, as the saying goes. Anne, I too find cruelty to animals abhorrent.

I too hate animal cruelty and wish it was not in the story. And I now officially hate Henry Gowan. (I already disliked Blandois, now it is hate.)

I too hate animal cruelty and wish it was not in the story. And I now officially hate Henry Gowan. (I already disliked Blandois, now it is hate.)I find it strange that Gowan mentions murder when talking about the painting of Blandois.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Robin P wrote: "Amy continues to be saintly, never protesting at all the criticism thrown at her, or even forthrightly stating her feelings except in the letter to Arthur ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Robin P wrote: "Amy continues to be saintly, never protesting at all the criticism thrown at her, or even forthrightly stating her feelings except in the letter to Arthur ..."Hmmm. I don't want t..."